Computer theft—especially laptop theft—is a growing problem for businesses and individuals alike. The loss of a computer system can be merely annoying or can be an expensive ordeal. But if the computer contains information that is irreplaceable or extraordinarily sensitive, it can be devastating.

Fortunately, by following a small number of simple and inexpensive measures, you can dramatically reduce the chance that your laptop or desktop computer will be stolen.

People steal computer systems for a wide variety of reasons. Many computer systems are stolen for resale—either the complete system or, in the case of sophisticated thieves, the individual components, which are harder to trace. Other computers are stolen by people who cannot afford to purchase their own computers. Still others are stolen for the information that they contain, usually by people who wish to obtain the information but sometimes by those who simply wish to deprive the computer’s owner of the use of the information. No matter why a computer is stolen, most computer thefts have one common element: opportunity. In most cases, computers are stolen because they have been left unprotected.

Laptops and other kinds of portable computers present a special hazard. They are easily stolen, difficult to tie down (they then cease to be portable!), and easily resold. Personnel with laptops should be trained to be especially vigilant in protecting their computers. In particular, theft of laptops in airports has been reported to be a major problem.

One way to minimize laptop theft is to make the laptops harder to resell. You can do this by engraving a laptop with your name and telephone number. (Do not engrave the laptop with your Social Security number, as this will enable a thief to cause you other problems!) See Section 8.3.2.2 for additional suggestions.

Laptop theft may not be motivated by resale potential. Often, competitive intelligence is more easily obtained by stealing a laptop with critical information than by hacking into a protected network. Thus, good encryption on a portable computer is critical.

One good way to protect your computer from theft is to physically secure it. A variety of physical tie-down devices are available to bolt computers to tables or cabinets. Although they cannot prevent theft, they make it more difficult.

Mobility is one of the great selling points of laptops. It is also the key feature that leads to laptop theft. One of the best ways to decrease the chance of having your laptop stolen is to lock it, at least temporarily, to a desk, a pipe, or another large object.

Most laptops sold today are equipped with a security slot (see Figure 8-1). For less than $50 you can purchase a cable lock that attaches to a nearby object and locks into the security slot. Once set, the lock cannot be removed without either using the key or damaging the laptop case, which makes it very difficult to resell the laptop. These locks prevent most grab-and-run laptop thefts. One of the largest suppliers of laptop locks is Kensington, which holds several key patents, although Kryptonite now makes a line of laptop locks as well.

Another way to decrease the chance of theft for resale and increase the likelihood of return is to tag your computer equipment with permanent or semipermanent equipment tags. Tags work because it is illegal to knowingly buy or sell stolen property—the tags make it very difficult for potential buyers or sellers to claim that they didn’t know that the computer was stolen.

The best equipment tags are clearly visible and individually serial-numbered so that an organization can track its property. A low-cost tagging system is manufactured by Secure Tracking of Office Property (http://www.stoptheft.com) (see Figure 8-2). These tags are individually serial-numbered and come with a three-year tracking service. If a piece of equipment with a STOP tag is found, the company can arrange to have it sent by overnight delivery back to the original owner. An 800 number on the tag makes returning the property easy.

Figure 8-2. The STOP tag is a simple and effective way to label your laptop (reprinted with permission)

According to the company, many reports of laptop “theft” in airports are actually cases in which a harried traveler accidentally leaves a laptop at a chair or table when they are running for a flight (or in an airport bar after a long wait for a flight).[97] The STOP tag makes it easier for airport personnel to return the laptop than to keep it.

STOP tags are affixed to the laptop’s case with a special adhesive that is rated for 800 pounds if properly applied. Underneath the tag is a tattoo that will embed itself in plastic cases. Should the tag be removed, the words “Stolen Property” and STOP’s 800-number remain visible.

STOP tags are used by many universities, businesses, and the U.S. government. No laptop should be without one.

Several companies now sell PC “tracing” programs. The tracing program hides in several locations on a laptop and places a call to the tracing service on a regular basis to reveal its location. The calls can be made using either a telephone line or an IP connection. Normally these “calls home” are ignored, but if the laptop is reported stolen to the tracing service, the police are notified about the location of the stolen property.

Laptop recovery software works quite well, but it typically cannot survive a complete reformat of the computer’s hard disk. Of course, as few thieves actually reformat the hard disks of computers that they steal, this usually isn’t a problem.

Absolute Software Corporation’s Computrace (http://www.computrace.com) tracking system costs under $60 and requires a PC running DOS or Windows. Similar systems have yet to appear for Unix machines.

Of course, many of these systems work on desktop systems as well as laptops. Thus, you can protect systems that you believe have a heightened risk of being stolen.

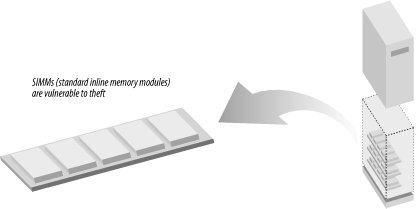

At times when RAM has been expensive, businesses and universities have suffered a rash of RAM thefts. Thieves enter offices, open computers, and remove some or all of the computer’s RAM (see Figure 8-3). Many computer businesses and universities have also had major thefts of advanced processor chips. RAM and late-model CPU chips are easily sold on the open market. They are virtually untraceable. And, when thieves steal only some of the RAM inside a computer, weeks or months may pass before the theft is noticed.

When the market is right, high-density RAM modules and processor cards can be worth their weight in gold. If a user complains that a computer is suddenly running more slowly than it did the day before, check its RAM, and then check to see that its case is physically secured.

If your computer is stolen, the information it contains will be at the mercy of the equipment’s new “owners.” They may erase it or they may read it. Sensitive information can be sold, used for blackmail, or used to compromise other computer systems.

You can never make something impossible to steal. But you can make stolen information virtually useless—provided that it is encrypted and the thief does not know the encryption key. For this reason, even with the best computer security mechanisms and physical deterrents, sensitive information should be encrypted using an encryption system that is difficult to break. We recommend that you acquire and use a strong encryption system so that even if your computer is stolen, the sensitive information it contains will not be compromised. Chapter 7 contains detailed information on encryption.

[97] There is some anecdotal evidence that forgetful travelers find it easier to report to management that their laptop was stolen than to admit that they forgot it!