One of the oldest and best known distributed administrative database systems is Sun’s Network Information Service (NIS). It was superseded years ago by NIS+, an enhanced but more complex successor to NIS, also by Sun. More recently, LDAP (Lightweight Directory Access Protocol) servers have become more popular, and Sun users are migrating to LDAP-based services. However, even though NIS has been deprecated by Sun, it is still widely used in many environments. As such, it is worth describing.

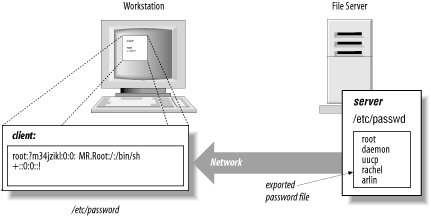

NIS is a distributed database system that lets many computers share password files, group files, host tables, and other files over the network. Although the files appear to be available on every computer, they are actually stored on only a single computer, called the NIS master server (and possibly replicated on a backup, secondary server, or slave server ). The other computers on the network, NIS clients, can use the databases (such as /etc/passwd) stored on the master server as if they were stored locally. These databases are called NIS maps.

With NIS, a large network can be managed more easily because all of the account and configuration information (such as the /etc/passwd file) can be stored and maintained on a single machine yet used on all the systems in the network.

Some files are replaced by their NIS maps. Other files are augmented. For these files, NIS uses the plus sign ( +) to tell the client system that it should stop reading the file (e.g., /etc/passwd) and should start reading the appropriate map (e.g., passwd). The plus sign instructs the Unix programs that scan that database file to query the NIS server for the remainder of the file. The server retrieves this information from the NIS map. The server maintains multiple maps, normally corresponding to files stored in the /etc directory, such as /etc/passwd, /etc/hosts, and /etc/services. This structure is shown in Figure 14-1.

For example, the /etc/passwd file on a client might look like this:

root:si4N0jF9Q8JqE:0:1:Mr. Root:/:/bin/sh +::0:0:::

This causes the program reading /etc/passwd on the client to make a network request to read the passwd map on the server. Normally, the passwd map is built from the server’s /etc/passwd file, although this need not necessarily be the case.

You can restrict the importing of accounts to particular users by following the + symbol with a particular username. For example, to include only the user george from your NIS server, you could use the following entry in your /etc/passwd file:

root:si4N0jF9Q8JqE:0:1:Mr. Root:/:/bin/sh +george::120:5:::

Note that we have included a UID and GID for george. You must include some UID and GID so that the function getpwuid ( ) will work properly. However, getpwuid ( ) actually goes to the NIS map and overrides the UID and GID values that you specify.[188]

You can also exclude certain usernames from being imported by inserting a line that begins with a minus sign (-). When NIS is scanning the /etc/passwd file, it will stop when it finds the first line that matches. Therefore, if you wish to exclude a specific account but include others that are on the server, you must place the lines beginning with the - symbol before the lines beginning with the + symbol.

For example, to exclude zachary’s account and include the others from the server, you might use the following /etc/passwd file:

root:si4N0jF9Q8JqE:0:1:Mr. Root:/:/bin/sh -zachary::2001:102::: +::999:999:::

Note again that we have included zachary’s UID and GID.

NIS allows you to selectively import some fields from the /etc/passwd database but not others. For example, if you have the following entry in your /etc/passwd file:

root:si4N0jF9Q8JqE:0:1:Mr. Root:/:/bin/sh +:*:999:999:::

then all of the entries in the NIS passwd map

will be imported, but each will have its password entry changed to

"*“, effectively

preventing it from being used on the client machine.[189]

Why might you want to do that? Well, by importing the entire map, you get all the UIDs and account names so that ls -l invocations show the owner of files and directories as usernames. The entry also allows the ~user notation in the various shells to correctly map to the user’s home directory (assuming that it is mounted using NFS). But it prevents the users in the map from actually logging onto the client system.

When you configure an NIS server, you must specify the server’s NIS domain. These domains are not the same as DNS domains. While DNS domains specify a region of the Internet, NIS domains specify an administrative group of machines.

The Unix domainname command is used to display and change your domain name. Without an argument, the command prints the current domain:

% domainname

EXPERT

%You can specify an argument to change your domain:

# domainname BAR-BAZ

#Note that you must be the superuser to set your computer’s domain. Under Solaris 2.x, the computer’s domain name is stored in the file /etc/defaultdomain and is usually set automatically on system startup by the shell script /etc/rc2.d/S69inet. A computer can be in only one NIS domain at a time, but it can serve any number of NIS domains.

Warning

Although you might be tempted to use your Internet domain as your netgroup domain, we strongly recommend against this. Setting the two domains to the same name has caused problems with some versions of sendmail. It is also a security problem to use an NIS domain that can be easily guessed. Hacker toolkits that attempt to exploit NIS or NFS bugs almost always try variations of the Internet domain name as the NIS domain name before trying anything else. (Of course, the domain name can still be determined in other ways.)

NIS netgroups allow you to create groups for users or machines on your network. Netgroups are similar in principle to Unix groups for users, but they are much more complicated.

The primary purpose of netgroups is to simplify your configuration files, and to give you less opportunity to make a mistake. By properly specifying and using netgroups, you can increase the security of your system by limiting the individuals and the machines that have access to critical resources.

The netgroup database is kept on the NIS master server in the file /etc/netgroup or /usr/etc/netgroup. This file consists of one or more lines that have the form:

groupname member1 member2 ...Each member can specify a host, a user, and an NIS domain. The members have the form:

(hostname, username, domainname)If a username is not included, then every user at the host

hostname is a member of the group. If a

domain name is not provided, then the current domain is

assumed.[190]

Here are some sample netgroups:

-

Profs (cs,bruno,hutch) (cs,art,hutch) This statement creates a netgroup called Profs, which is defined to be the users bruno and art on the machine cs in the domain hutch.

-

Servers (oreo,,) (choco,,) (blueberry,,) This statement creates a netgroup called Servers, which matches any user on the machines oreo, choco, or blueberry in the current domain.

-

Karen_g (,karen,) This statement creates a netgroup called Karen_g which matches the user karen on any machine.

-

Universal(,,,) This statement creates the Universal netgroup, which matches anybody on any machine.

-

MachinesOnly (,- , ) This statement creates a netgroup that matches all hostnames in the current domain but has no user entries. In this case, the minus sign is used as a negative wildcard.

The /etc/yp/makedbm program (sometimes found in /usr/etc/yp/makedbm) processes the netgroup file into a number of database files that are stored in:

| /etc/yp/domainname/netgroup.dir |

| /etc/yp/domainname/netgroup.pag |

| /etc/yp/domainname/netgroup.byuser.dir |

| /etc/yp/domainname/netgroup.byuser.pag |

| /etc/yp/domainname/netgroup.byhost.dir |

| /etc/yp/domainname/netgroup.byhost.pag |

Note that /etc/yp may be symbolically linked to /var/yp on some machines.

If you have a small organization, you might simply create two netgroups: one for all of your users, and a second for all of your client machines. These groups will simplify the creation and administration of your system’s configuration files.

If you have a larger organization, you might create several groups. For example, you might create a group for each department’s users. You could then have a master group that consists of all of the subgroups. Of course, you could do the same for your computers as well.

Consider the following science department:

Math (mathserve,,) (math1,,) (math2,,) (math3,,) Chemistry (chemserve1,,) (chemserve2,,) (chem1,,) (chem2,,) (chem3,,) Biology (bioserve1,,) (bio1,,) (bio2,,) (bio3,,) Science Math Chemistry Biology

Netgroups are important for security because you use them to limit which users or machines on the network can access information stored on your computer. You can use netgroups in NFS files to limit who has access to the partitions, and in datafiles such as /etc/passwd to limit which entries are imported into a system.

You can use the netgroups facility to control which accounts are imported by the /etc/passwd file. For example, if you want to simply import accounts for a specific netgroup, then follow the plus sign (+) with an at sign (@) and a netgroup:

root:si4N0jF9Q8JqE:0:1:Mr. Root:/:/bin/sh +@operators::999:999:::

The above will bring in the NIS password map entry for the users listed in the operators group.

You can also exclude users or groups if you list the exclusions before you list the netgroups. For example:

root:si4N0jF9Q8JqE:0:1:Mr. Root:/:/bin/sh -george::120:5::: -@suspects::999:999::: +::999:999:::

The above will include all NIS password map entries except for user george and any users in the suspects netgroup.

NIS has been the starting point for many successful penetrations into Unix networks. Because NIS controls user accounts, if you can convince an NIS server to broadcast that you have an account, you can use that fictitious account to break into a client on the network. NIS can also make confidential information, such as encrypted password entries, widely available.

There are design flaws in the code of the NIS implementations of several vendors that allow a user to reconfigure and spoof the NIS system. This spoofing can be done in two ways: by spoofing the underlying RPC system, and by spoofing NIS.

As we noted in Chapter 13, the NIS system depends on the functioning of the portmapper service. This is a daemon that matches supplied service names for RPC with IP port numbers at which those services can be contacted. Servers using RPC will register themselves with portmapper when they start and will remove themselves from the portmap database when they exit or reconfigure.

Early versions of portmapper allowed any program to register itself as an RPC server, allowing attackers to register their own NIS servers and respond to requests with their own password files. Sun’s current version of portmapper rejects requests to register or delete services if they come from a remote machine, or if they refer to a privileged port and come from a connection initiated from an unprivileged port.[191] Thus, in Sun’s version, only the superuser can make requests that add or delete service mappings to privileged ports, and all requests can only be made locally. However, not every vendor’s version of the portmapper daemon performs these checks. The result is that an attacker might be able to replace critical RPC services with his own booby-trapped versions.

Note that NFS and some NIS services often register on unprivileged ports, even on Sun systems. In theory, even with the checks outlined above, an attacker could replace one of these services with a specially written program that would respond to system requests in a way that would compromise system security. This would require some in-depth understanding of the protocols and relationships of the programs, but these are well-documented and widely known.

NIS clients get information from an NIS server through RPC calls. A local daemon, ypbind, caches contact information for the appropriate NIS server daemon, ypserv. The ypserv daemon may be local or remote.

Under early SunOS versions of the NIS service (and possibly versions by some other vendors), it was possible to instantiate a program that acted like ypserv and responded to ypbind requests. The local ypbind daemon could then be instructed to use that program instead of the real ypserv daemon. As a result, an attacker could supply her own version of the password file, for example, to a login request! (The security implications of this should be obvious.)

Current NIS implementations of ypbind have a -secure command-line flag (sometimes present as simply -s) that can be provided when the daemon is started. If the flag is used, the ypbind daemon will not accept any information from a ypserv server that is not running on a privileged port. Thus, a user-supplied attempt to masquerade as the ypserv daemon will be ignored. A user can’t spoof ypserv unless that user already has superuser privileges. In practice, there is no good reason not to use the -secure flag.

Unfortunately, the -secure flag has a flaw. If the attacker is able to subvert the root account on a machine on the local network and start a version of ypserv using his own NIS information, he need only point the target ypbind daemon to that server. The compromised server would be running on a privileged port, so its responses would not be rejected. The ypbind process would therefore accept its information as valid, and security could be compromised.

An attacker could also write a “fake” ypserv that runs on a PC-based system. Privileged ports have no meaning on PCs, so the fake server could feed any information to the target ypbind process.

A combination of installation mistakes and changes in NIS itself has caused some confusion with respect to the NIS plus sign (+) in the /etc/passwd file.

If you use NIS, be very careful that the plus sign is in the /etc/passwd file of your clients and not your servers. On an NIS server, the plus sign can be interpreted as a username under some versions of the Unix operating system. The simplest way to avoid this problem is to make sure that you do not have the + account on your NIS server.

Attempting to figure out what to put on your client machine is another matter. With early versions of NIS, the following line was distributed:

+::0:0::: Correct on SunOS and SolarisUnfortunately, this line presented a problem. When NIS was not

running, the plus sign was sometimes taken as an account name, and

anybody could log into the computer by typing

+ at the login:

prompt—and without a password! Even worse, the person logged in

with superuser privileges.[192]

One way to minimize the danger was to include a password field for the plus user. One specified the plus sign line in the form:

+:*:0:0::: On NIS clients onlyUnfortunately, under some versions of NIS this entry actually means

“import the passwd map, but

change all of the encrypted passwords to

*“—which effectively

prevents everybody from logging in. This entry isn’t

right either!

The easiest way to see how your system behaves is to attempt to log into your NIS clients and servers using a + as a username. You may also wish to try logging in with the network cable unplugged to simulate what happens to your computer when the NIS server cannot be reached. In either case, you should not be able to log in by simply typing + as a username. This approach will tell you that your server is properly configured.

If you see the following example, you have no problem:

login:+password:anythingLogin incorrect

If you see the following example, you do have a problem:

login: +

Last login: Sat Aug 18 16:11 32 on ttya

#If you are running a recent version of your operating system, do not think that your system is immune to the + confusion in the NIS subsystem. In particular, some NIS versions on Linux got this wrong too.

Because NIS has relatively weak security, it can disclose information about your site to attackers. In particular, NIS can disclose encrypted passwords, usernames, hostnames and their IP addresses, and mail aliases.

Unless you protect your NIS server with a firewall or with a modified portmapper process, anyone on the outside of your system can obtain copies of the databases exported by your NIS server. To do this, all the outsider needs to do is guess the name of your NIS domain, bind to your NIS server using the ypset command, and request the databases. This can result in the disclosure of your distributed password file, and all the other information contained in your NIS databases.

There are several ways to prevent unauthorized disclosure of your NIS databases:

The simplest way is to protect your site with a firewall, or at least a smart router, and not allow the UDP packets associated with RPC to cross between your internal network and the outside world. Unfortunately, because RPC is based on the portmapper, the actual UDP port that is used is not fixed. In practice, the only safe strategy is to block all UDP packets except those that you specifically wish to let cross.

Another approach is to use a portmapper program that allows you to specify a list of computers (by hostname or IP address) that should be allowed or denied access to specific RPC servers.[193] If you don’t have a firewall, an attacker can still attempt to scan for each individual RPC service without consulting the portmapper, but if they do make an attempt at the portmapper first, an improved version may give you warning.

Some versions of NIS support the use of the /var/yp/securenets file for NIS servers. This file, when present, can be used to specify a list of networks that may receive NIS information. Other versions may provide other ways for the ypserv daemon to filter addresses that are allowed to access particular RPC servers.

Don’t tighten up NIS but forget about DNS! If you decide that outsiders should not be able to learn your site’s IP addresses, be sure to run two nameservers: one for internal use and one for external use.

[188] This may not be true in every NIS implementation. It certainly isn’t the way we would design it.

[189] And no, it does not make the UID and GID of all imported entries 999, despite those values being present. Expecting consistency in Unix is a well-worn path to trouble.

[190] It is best to create netgroups in which every member has a given username (a netgroup of users) or in which every member has a hostname but does not have a username (a netgroup of hosts). Creating netgroups in which some members are users and some members are hosts makes mistakes somewhat more likely.

[191] Remember, however, that privileged ports are a weak form of authentication.

[192] On Sun’s NIS implementation, and possibly others, this danger can be ameliorated somewhat by avoiding 0 or other local user values as the UID and GID values in NIS entries in the passwd file.

[193] This same functionality is built into many vendor versions, but you need to read the documentation carefully to find out how to use it. It is usually turned off by default.