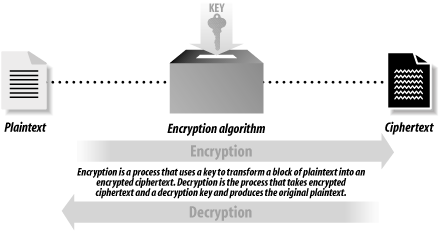

Cryptography is a collection of mathematical techniques for protecting information. Using cryptography, you can transform written words and other kinds of messages so that they are unintelligible to anyone who does not possess a specific mathematical key necessary to unlock the message. The process of using cryptography to scramble a message is called encryption . The process of unscrambling the message by use of the appropriate key is called decryption . Figure 7-1 illustrates how these two processes fit together.

Cryptography is used to prevent information from being accessed by an unauthorized recipient. In theory, once a piece of information is encrypted, the encrypted data can be accidentally disclosed or intercepted by a third party without compromising the security of the information, provided that the key necessary to decrypt the information is not disclosed and that the method of encryption will resist attempts to decrypt the message without the key.

For example, here is a message that you might want to encrypt:

SSL is a cryptographic protocol

And here is how the message might look after it has been encrypted:

Ç'@%[»FÇ«;$TfiP∑|x¿EûóõÑ%ß+ö~·...aÜ"BÆuâw

Because the decryption key is not shown, it should not be practical to take the preceding line of gibberish and turn it back into the original message.

The science of cryptography is thousands of years old. In his book The Code Breakers, David Kahn traces the roots of cryptography back to ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome. For example, writes Kahn, Greek generals used cryptography to send coded messages to commanders who were in the field. In the event that a messenger was intercepted by the enemy, the message’s content would not be revealed.

Most cryptographic systems have been based on two techniques: substitution and transposition:

- Substitution

Substitution is based on the principle of replacing each letter in the message you wish to encrypt with another one. The Caesar cipher, for example, substitutes the letter “a” with the letter “d,” the letter “b” with the letter “e,” and so on. Some substitution ciphers use the same substitution scheme for every letter in the message that is being encrypted; others use different schemes for different letters.

- Transposition

Transposition is based on scrambling the characters that are in the message. One transposition system involves writing a message into a table row by row, then reading it out column by column. Double transposition ciphers involve using two such transformations.

In the early part of the 20th century, a variety of electromechanical devices were built in Europe and the United States for the purpose of encrypting messages sent by telegraph or radio. These systems relied principally on substitution because there was no way to store multiple characters necessary to use transposition techniques. Today, encryption algorithms running on high-speed digital computers use substitution and transposition in combination, as well as other mathematical functions.

Cryptography is a “dual-use” technology—that is, cryptography has both military and civilian applications. There are many other examples of dual-use technologies, including carbon fibers, high-speed computers, and even trucks. Historically, cryptography has long been seen as a military technology.[78] Nearly all of the historical examples of cryptography, from Greece and Rome into the modern age, are stories of armies, spies, and diplomats who used cryptography to shield messages transmitted across great distances. There was Julius Caesar, who used a simple substitution cipher to scramble messages sent back from Gaul. Mary, Queen of Scots, tried to use cryptography to protect the messages that she sent to her henchmen who were planning to overthrow the British Crown. And, of course, Hitler used the Enigma encryption cipher to scramble messages sent by radio to the German armies and U-Boats during World War II.

There is also a tradition of nonmilitary use of cryptography that is many centuries old. There are records of people using cryptography to protect religious secrets, to hide secrets of science and industry, and to arrange clandestine romantic trysts. In Victorian England, lovers routinely communicated by printed encrypted advertisements in the London newspapers. Lovers again relied on encryption during World War I when mail sent between the U.S. and foreign countries was routinely opened by Postal Service inspectors looking for communiqués between spies. These encrypted letters, when they were intercepted, were sent to Herbert Yardley’s offices in New York City, which made a point of decrypting each message before it was resealed and sent along its way. As Herbert Yardley wrote in his book The American Black Chamber, lovers accounted for many more encrypted letters than did spies—but almost invariably the lovers used weaker ciphers! The spies and the lovers both used cryptography for the same reason: they wanted to be assured that, in the event that one of their messages was intercepted or opened by the wrong person, the letter’s contents would remain secret. Cryptography was used to increase privacy.

In recent years, the use of cryptography in business and commerce appears to have far eclipsed all uses of cryptography by all the world’s governments and militaries. These days, cryptography is used to scramble satellite television broadcasts, protect automatic teller networks, and guard the secrecy of practically every purchase made over the World Wide Web. Indeed, cryptography made the rapid commercialization of the Internet possible: without cryptography, it is doubtful that banks, businesses, and individuals would have felt safe doing business online. For all of its users, cryptography is a way of ensuring certainty and reducing risk in an uncertain world.

Let’s return to the example introduced at the beginning of this chapter. Here is that sample piece of plaintext again:

SSL is a cryptographic protocol

This message can be encrypted with an encryption algorithm to produce an encrypted message. The encrypted message is called a ciphertext.

In the next example, the message is encrypted using the

Data

Encryption Standard (DES).[79] The DES is a

symmetric algorithm, which means that it uses the same key for

encryption as for decryption. The encryption key is

nosmis:

% des -e < text > text.des

Enter key: nosmis

Enter key again: nosmis

%The result of the encryption is this encrypted message:[80]

% cat text.des

Ç'@%[»FÇ«;$TfiP∑|x¿EûóõÑ%ß+ö~·...aÜ"BÆuâwAs you can see, the encrypted message is nonsensical. But when this

message is decrypted with the key nosmis, the

original message is produced:

%des -d < text.des > text.decryptEnter key: nosmis Enter key again: nosmis %cat text.decryptSSL is a cryptographic protocol %

If you try to decrypt the encrypted message with a different key,

such as gandalf, the result is garbage:[81]

%des -d < text.des > text.decryptEnter key: gandalf Enter key again: gandalf Corrupted file or wrong key %cat text.decrypt±N%EÒR...f'"H;0ªõO>",,!_+í∞>

The only way to decrypt the encrypted message and get printable text

is by knowing the secret key nosmis. If you

don’t know the key, and you need the contents of the

message, one approach is to try to decrypt the message with every

possible key.

This approach

is called a key search

attack

or a brute force

attack

.

How easy is a brute force attack? That depends on the length of the key. Our sample message was encrypted with the DES algorithm, which has a 56-bit key. Each bit in the 56-bit key can be a 1 or a 0. As a result, there are 256—that is, 72,057,594,037,900,000—different keys. Although this may seem like a lot of keys, it really isn’t. If you could try a billion keys each second and could recognize the correct key when you found it (quite possible with a network of modern computers), you could try all possible keys in a little less than 834 days.

And, in fact, DES is even less secure than the example implies. The Unix des command does a very poor job of transforming a typed “key” into the key that’s actually used by the encryption algorithm. A typed key will typically include only the 96 printable characters, reducing the keyspace to 968 possible keys—this number is only one-tenth the size of 256. If you can search a billion keys a second, you could try all of these keys in only 83 days.

We’ll discuss these issues more thoroughly in Section 7.2.2 later in this chapter.

There are fundamentally two kinds of encryption algorithms:

- Symmetric key algorithms

With these algorithms, the same key is used to encrypt and decrypt the message. The DES algorithm discussed earlier is a symmetric key algorithm. Symmetric key algorithms are sometimes called secret key algorithm s, or private key algorithms . Unfortunately, both of these names are easily confused with public key algorithms, which are unrelated to symmetric key algorithms.

- Asymmetric key algorithms

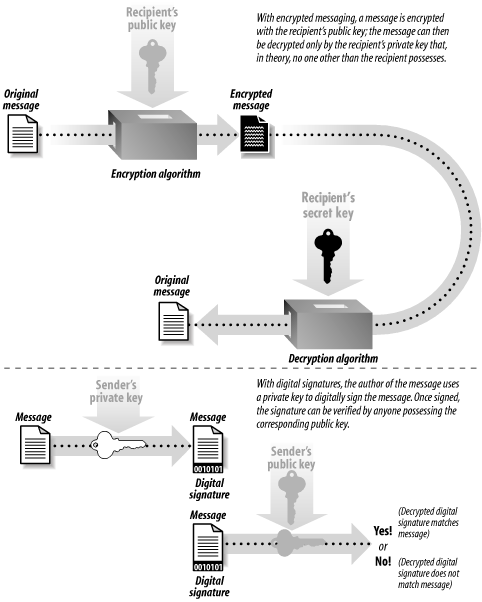

With these algorithms, one key is used to encrypt the message and another key to decrypt it. A particularly important class of asymmetric key algorithms is public key systems. The encryption key is normally called the public key in these algorithms because it can be made publicly available without compromising the secrecy of the message or the decryption key. The decryption key is normally called the private key or secret key.

This technology was invented independently by academic cryptographers at Stanford University and by military cryptographers at England’s GCHQ, who called the techniques two-key cryptography. (The U.S. National Security Agency may have also invented and shelved the technology as a novelty, notes Carl Ellison.) This technology is a recent development in the history of cryptography.

Symmetric key algorithms are the workhorses of modern cryptographic systems. They are generally much faster than public key algorithms. They are also somewhat easier to implement. And it is generally easier for cryptographers to ascertain the strength of symmetric key algorithms. Unfortunately, symmetric key algorithms have three problems that limit their use in the real world:

For two parties to securely exchange information using a symmetric key algorithm, those parties must first exchange an encryption key. Alas, exchanging an encryption key in a secure fashion can be quite difficult.

As long as they wish to send or receive messages, both parties must keep a copy of the key. This doesn’t seem like a significant problem, but it is. If one party’s copy is compromised and the second party doesn’t know this fact, then the second party might send a message to the first party—and that message could then be subverted using the compromised key.

If each pair of parties wishes to communicate in private, then they need a unique key. This requires (N 2 - N)/2 keys for N different users. For 10 users that is 45 keys. This may not seem like much, but consider the Internet, which has perhaps 300,000,000 users. If you wanted to communicate with each of them, you’d need to store 299,999,999 keys on your system in advance. And if everyone wanted to communicate privately with everyone else, that would require 44,999,999,850,000,000 unique keys (almost 45 quadrillion)!

Public key algorithms overcome these problems. Instead of a single key, public key algorithms use two keys: one for encrypting the message, the other for decrypting the message. These keys are usually called the public key and the private key.

In theory, public key technology (illustrated in Figure 7-2) makes it relatively easy to send somebody an encrypted message. People who wish to receive encrypted messages will typically publish their keys in directories or otherwise make their keys readily available. Then, to send somebody an encrypted message, all you have to do is get a copy of her public key, encrypt your message, and send it to her. With a good public key system, you know that the only person who can decrypt the message is the person who has possession of the matching private key. Furthermore, all you really need to store on your own machine is your private key (though it’s convenient and unproblematic to have your public key available as well).

Public key cryptography can also be used for creating digital signatures . Similar to a real signature, a digital signature is used to denote authenticity or intention. For example, you can sign a piece of electronic mail to indicate your authorship in a manner akin to signing a paper letter. And, as with signing a bill of sale agreement, you can electronically sign a transaction to indicate that you wish to purchase or sell something. With public key technology, you use the private key to create the digital signature; others can then use your matching public key to verify the signature.

Unfortunately, public key algorithms have a significant problem of their own: they are computationally expensive.[82] In practice, public key encryption and decryption require as much as 1,000 times more computer power than an equivalent symmetric key encryption algorithm.

To get both the benefits of public key technology and the speed of symmetric encryption systems, most modern encryption systems actually use a combination. With hybrid public/private cryptosystems , slower public key cryptography is used to exchange a random session key , which is then used as the basis of a private (symmetric) key algorithm. (A session key is used only for a single encryption session and is then discarded.) Nearly all practical public key cryptography implementations are actually hybrid systems.

There is also a special class of functions that are almost always used in conjunction with public key cryptography: message digest functions. These algorithms are not encryption algorithms at all. Instead, they are used to create a “fingerprint” of a file or a key. A message digest function generates a seemingly random pattern of bits for a given input. The digest value is computed in such a way that finding a different input that will exactly generate the given digest is computationally infeasible. Message digests are often regarded as fingerprints for files. Most systems that perform digital signatures encrypt a message digest of the data rather than the actual file data itself.

The following sections look at these classes of algorithms in detail.

[78] Ironically, despite the fact that cryptography has been primarily used by the military, historically, the strongest publicly known encryption systems were invented by civilians. Encryption has long been used to protect commerce and hide secret romances, and at times these uses have dominated the political and military uses of cryptography. For more details, see Carl Ellison’s essay at http://world.std.com/~cme/html/timeline.html or read Kahn’s book.

[79] To be precise, we will use the DEA, the Data Encryption Algorithm, which conforms to the DES. Nearly everyone refers to it as the DES instead of the DEA, however.

[80] Modern encrypted messages are inherently binary data. Because of the limitations of paper, not all control characters are displayed.

[81] In the example, the des command prints the message “Corrupted file or wrong key” when we attempt to decrypt the file text.des with the wrong key. How does the des command know that the key provided is incorrect? The answer has to do with the fact that DES is a block encryption algorithm, encrypting data in blocks of 64 bits at a time. When a file is not an even multiple of 64 bits, the des command pads the file with null characters (ASCII 0). It then inserts at the beginning of the file a small header indicating how long the original file “really was.” During decryption, the des command checks the end of the file to make sure that the decrypted file is the same length as the original file. If it is not, then something is wrong: either the file was corrupted or the wrong key was used to decrypt the file. Thus, by trying all possible keys, it is possible to use the des command to experimentally determine which of the many possible keys is the correct one. But don’t worry: there are a lot of keys to try.

[82] The previous edition of this book used the words “quite slow” instead of “computationally expensive.” With modern computers, a public key operation can actually be quite fast—an encryption or decryption can frequently be performed in less than a second. But while that may seem fast, such a delay can be significant on a web server that is serving millions of web pages every day. This is why we use the phrase “computationally expensive.”