Although passwords are an important element of computer security, users often receive only cursory instructions about selecting them.

If you are a user, be aware that by picking a bad password—or by revealing your password to an untrustworthy individual—you are potentially compromising your entire computer’s security. If you are a system administrator, you should make sure that all of your users are familiar with the issues raised in this section.

A bad password is any password that is easily guessed.

In the movie Real Genius, a computer recluse

named Laszlo Hollyfeld breaks into a top-secret military computer

over the telephone by guessing passwords. Laszlo starts by typing the

password AAAAAA, then trying

AAAAAB, then AAAAAC, and so on,

until he finally finds the password that matches.

Real-life

computer crackers are far more sophisticated. Instead of typing each

password by hand, attackers use their computers to open network

connections (or make phone calls) then try the passwords,

automatically retrying when they are disconnected. Instead of trying

every combination of letters, starting with AAAAAA

(or whatever), attackers use

hit lists of common passwords such as

wizard or demo. Even a modest

home computer with a good password-guessing program can try many

thousands of passwords in less than a day’s time.

Some hit lists used by crackers are several hundred thousand words in

length, and include words in many different languages.[35]

Therefore, a password that anybody on the

planet

[36]

might use for a password is probably a bad password choice for you.

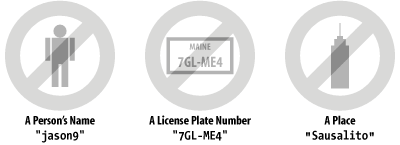

What’s a popular and bad password? Some examples are

your name, your partner’s name, or your

parents’ names. Other bad passwords are these names

backwards or followed by a single digit. Short passwords are also

bad, because there are fewer of them: they are, therefore, more

easily guessed. Especially bad are “magic

words” from computer games, such as

xyzzy. Magic words look secret and unguessable,

but in fact they are widely known. Other bad choices include phone

numbers, characters from your favorite movies or books, local

landmark names, favorite drinks, or famous computer scientists (see

the sidebar Bad Passwords for still more bad choices).

These words backwards or capitalized are also weak. Replacing the

letter “l” (lowercase

“L”) with

“1” (numeral one), the letter

“o” with

“0” (numeral zero), or

“E” with

“3,” adding a digit to either end,

or other simple modifications of common words are also weak. Words in

other languages are no better. Dictionaries for dozens of languages

are available for download on the Internet, including Klingon! There

are also dictionaries available that consist solely of words

frequently chosen as passwords.

Many versions of Unix make a minimal attempt to prevent users from picking bad passwords. For example, under some versions of Unix, if you attempt to pick a password with fewer than six letters or letters that are all the same case, the passwd program will ask the user to “Please pick a different password” followed by some explanation of the local requirements for a password. After three tries, however, some versions of the passwd program relent and let the user pick a short one. Better versions allow the administrator to require a minimum number of letters, a requirement for nonalphabetic characters, and other restrictions. However, some administrators turn these requirements off because users complain about them! Users will likely complain more loudly if their computers are broken into.

Surprisingly, a significant percentage of all computers that do not explicitly check for bad passwords contain at least one account in which the username and the password are the same or extremely similar. Such accounts are often called “Joes.” Joe accounts are easy for crackers to find and trivial to penetrate. Attackers can find an entry point into far too many systems simply by checking every account to see whether it is a Joe account. This is one reason why it is dangerous for your computer to make a list of all of the valid usernames available to the outside world.

Good passwords are passwords that are difficult to guess. The best passwords are difficult to guess because they include some subset of the following characteristics:

Have both uppercase and lowercase letters

Have digits and/or punctuation characters as well as letters

May include some control characters and/or spaces[37]

Are easy to remember, so they do not have to be written down

Are seven or eight characters long.

Can be typed quickly, so somebody cannot determine what you type by watching over your shoulder

It’s easy to pick a good password. Here are some suggestions:

Take two short words and combine them with a special character or a number, like

robot4myoreye-con.Put together an acronym that’s special to you, like

Anotfsw(Ack, none of this fancy stuff works),aUpegcbm(All Unix programmers eat green cheese but me), orTtl*Hiww(Twinkle, twinkle, little star. How I wonder what . . . ).Create a nonsense word by alternating consonant and vowel sounds, like

huroMork. These words are usually easy to pronounce and remember.

Of course, robot4my, eye-con,

Anotfsw, Ttl*Hiww,

huroMork, and aUpegcbm are now

all bad passwords because they’ve been printed here.

If you have several computer accounts, you may wish to have the same password on every machine, so you have less you need to remember. This is called password synchronization.

Password synchronization can increase security if the synchronization allows you to use a good password that is hard to guess. Systems that provide for automated password synchronization make it easy to change your password and have that change reflected everywhere.

On the other hand, password synchronization can decrease security if the password is compromised—suddenly all of your accounts will be vulnerable! Even worse, with password synchronization you may not even know that your password has been compromised!

Password synchronization is also problematic for usernames and passwords that are used for web sites. Many people will use the same username and password at many web sites—even web sites that are potentially being run by untrustworthy individuals or organizations. A simple way to capture usernames and passwords is to set up a web site that offers “a chance of winning $10,000” to anybody who registers with an email address and sets up a password upon entry.

If you are thinking of using the same password on many machines, here are some points to consider:

One common approach used by people with accounts on many machines is to have a base password that can be modified for each different machine. For example, your base password might be

kxyzzyfollowed by the first letter of the name of the computer you’re using. On a computer named athena your password would bekxyzzya, while on a computer named ems your password would bekxyzzye. (Don’t, of course, use this exact method of varying your passwords.)Another common approach is to create a different, random password for each machine. Store these passwords in a file that is encrypted—either manually encrypted with a program such as PGP, or automatically encrypted using a “password keeper” program.

To simplify access to remote systems, configure your remote accounts for ssh-based access using your ssh key. Make sure that this key is kept encrypted using an ssh passphrase. For day-to-day use, the ssh passphrase is all that needs to be remembered. However, for special cases or when changing the password, you can refer to your encrypted file of all the passwords. See the manual page for ssh-keygen for specific instructions.

In the movie War Games, there is the canonical story about a high school student who breaks into his school’s academic computer and changes his grades; he does this by walking into the school’s office, looking at the academic officer’s terminal, and noting that the telephone number, username, and password are written on a Post-It note.

Unfortunately, the fictional story has actually happened—in fact, it has happened hundreds of times over.

Users are admonished to “never write down your password.” The reason is simple enough: if you write down your password, somebody else can find it and use it to break into your computer. A password that is memorized is more secure than the same password written down, simply because there is less opportunity for other people to learn it. On the other hand, a password that must be written down to be remembered is quite likely a password that is not going to be guessed easily.[38] If you write your password on something kept in your wallet, the chances of somebody who steals your wallet using the password to break into your computer account are remote indeed.[39]

If you must write down your password, then at least follow a few precautions:

When you write it down, don’t identify your password as being a password.

Don’t include the name of the account, network name, or phone number of the computer on the same piece of paper as your password.

Don’t attach the password to your terminal, keyboard, or any part of your computer.

Don’t write your actual password. Instead, disguise it by mixing in other characters or by scrambling the written version of the password in a way that you can remember. For example, if your password is

Iluvfred, you might writefredIluvorvfredxyIuor perhapsLastweek,IlostUncleVernon's`friedrice&eggplant delight'recipe--remembertocallhimafter3:00p.m.—to throw off a potential wallet-snatcher.[40]

Of course, you can always encrypt your passwords in a handy file on a machine where you remember the password. Many people store their passwords in an encrypted form on a PDA (handheld computer). The only drawback to this approach is when you can’t get to your file, or your PDA has gone missing (or its batteries die)—how do you log on to report the problem?

Here are some other things to avoid:

Don’t record a password online (in a file, database, or email message), unless the password is encrypted.

Likewise, never send a password to another user via electronic mail. In The Cuckoo’s Egg, Cliff Stoll tells of how a single intruder broke into system after system by searching for the word

passwordin text files and electronic mail messages. With this simple trick, the intruder learned of the passwords of many accounts on many different computers across the country.Don’t use your login password as the password of application programs. For instance, don’t use your login password as your password to an online MUD (multiuser dungeon) game or for a web server account. The passwords in those applications are controlled by others and may be visible to the wrong people.

Don’t use the same password for different computers managed by different organizations. If you do, and an attacker learns the password for one of your accounts, all will be compromised.

[35] In contrast, if you were to program a home computer to try all

6-letter combinations from AAAAAA to

ZZZZZZ, it would have to try 308,915,776 different

passwords. Guessing one password per second, that would require

nearly 10 years. Many Unix systems make this process even slower by

introducing delays between login attempts.

[36] If you believe that beings from other planets have access to your computer account, then you should not pick a password that they can guess, either, although this may be the least of your problems.

[37] In some cases, using spaces may be problematic. An attacker who is in a position to listen carefully can distinguish the sound of the space bar from the sound of other keys. Similarly, Shift or Control key combinations have a distinctive sound, but there are many shifted characters and only one space.

[38] We should note that in the 12 years since we originally wrote this, we have added lots more accounts and passwords and have more frequent “senior moments.” Thus, we perhaps should be a little less emphatic about this point.

[39] Unless, of course, you happen to be an important person, and your wallet is stolen or rifled as part of an elaborate plot. In their book Cyberpunks, authors John Markoff and Katie Hafner describe a woman named “Susan Thunder” who broke into military computers by doing just that: she would pick up an officer at a bar and go home with him. Later that night, while the officer was sleeping, Thunder would get up, go through the man’s wallet, and look for telephone numbers, usernames, and passwords.

[40] We hope that last one required some thought. The 3:00 p.m. means to start with the third word and take the first letter of every word. With some thought, you can come up with something equally obscure that you will remember.