Although every Unix user has a username consisting of one or more characters, inside the computer Unix represents the identity of each user by a single number: the user identifier (UID). Under most circumstances, each user is assigned his own unique ID.

Unix also uses special usernames for a variety of system functions. As with usernames associated with human users, system usernames usually have their own UIDs as well. Here are some common “users” on various versions of Unix:

- root

Superuser account. Performs accounting and low-level system functions.

- bin

Binary owner. Has ownership of system files on some systems but doesn’t typically execute programs.

- daemon

Handles some aspects of the network. This username is also associated with other utility systems, such as the print spoolers, on some versions of Unix.

Handles aspects of electronic mail. On many systems there is no mail user, and daemon is used instead.

- guest

Used (infrequently) for site visitors to access the system.

- ftp

Used for anonymous FTP access.

- uucp

Controls ownership of the Unix serial ports. (uucp traditionally managed the UUCP system, which is now deprecated.)

- news

Used for Usenet news.

- lp

Used for the printer system.[49]

- nobody

Owns no files and is sometimes used as a default user for unprivileged operations.

- www or http

Runs the web server.

- named

Runs the BIND name server.

- sshd

Performs unprivileged operations for the OpenSSH Secure Shell daemon.

- operator

Used for creating backups and (sometimes) for printer operation.

- games

Allowed to access high-score files.

- amanda

Used for the Amanda remote backup system.

On most Unix systems the user accounts are listed in the database file /etc/passwd; the corresponding passwords for these accounts are kept in a file named /etc/shadow, /etc/security/passwd, or /etc/master.passwd. To improve lookup speed, some systems compile the password file into a compact index file named something like /etc/pwd.db, which is used instead.

Here is an example of an /etc/passwd file from a Linux system containing a variety of system and ordinary users:

$ more /etc/passwd root:x:0:0:Mr. Root:/root:/bin/bash bin:x:1:1:Binary Installation User:/bin:/sbin/nologin daemon:x:2:2:daemon:/sbin:/sbin/nologin adm:x:3:4:adm:/var/adm:/sbin/nologin lp:x:4:7:lp:/var/spool/lpd:/sbin/nologin sync:x:5:0:sync:/sbin:/bin/sync shutdown:x:6:0:shutdown:/sbin:/sbin/shutdown halt:x:7:0:halt:/sbin:/sbin/halt mail:x:8:12:mail:/var/spool/mail:/sbin/nologin news:x:9:13:news:/var/spool/news: uucp:x:10:14:uucp:/var/spool/uucp:/sbin/nologin operator:x:11:0:operator:/root:/sbin/nologin games:x:12:100:games:/usr/games:/sbin/nologin gopher:x:13:30:gopher:/var/gopher:/sbin/nologin ftp:x:14:50:FTP User:/var/ftp:/sbin/nologin nobody:x:99:99:Nobody:/:/sbin/nologin mailnull:x:47:47::/var/spool/mqueue:/dev/null rpm:x:37:37::/var/lib/rpm:/bin/bash xfs:x:43:43:X Font Server:/etc/X11/fs:/bin/false ntp:x:38:38::/etc/ntp:/sbin/nologin rpc:x:32:32:Portmapper RPC user:/:/bin/false gdm:x:42:42::/var/gdm:/sbin/nologin rpcuser:x:29:29:RPC Service User:/var/lib/nfs:/sbin/nologin nfsnobody:x:65534:65534:Anonymous NFS User:/var/lib/nfs:/sbin/nologin nscd:x:28:28:NSCD Daemon:/:/bin/false ident:x:98:98:pident user:/:/sbin/nologin rachel:x:181:181:Rachel Cohen:/u/rachel:/bin/ksh ralph:x:182:182:Ralph Knox:/u/ralph:/bin/tcsh mortimer:x:183:183:Mortimer Merkle:/u/mortimer:/bin/sh

Notice that most of these accounts do not have “people names,” and that all have a password field of “x”. In the old days of Unix, the second field was used to hold the user’s encrypted password. This information is now stored in a second file, the shadow password file.

The /etc/passwd file can be thought of as a directory[50] that lists all of the users on the system. As we saw in the last chapter, it is possible to configure a Unix system to use other directory services, such as NIS, NIS+, LDAP, and Kerberos. (We’ll discuss directory services in detail in Chapter 14.) When these systems are used, the Unix operating system is often modified so that the utility programs still respond as if all of the accounts actually reside in a single /etc/passwd file.

UIDs are historically unsigned 16-bit integers, which means they can range from 0 to 65535. UIDs between 0 and 99 are typically used for system functions; UIDs for humans usually begin at 100 or 1000. Many versions of Unix now support 32-bit UIDs. A few older versions of Unix have UIDs that are signed 16-bit integers, ranging from -32768 to 32767.

There is one special UID, which is UID 0. This is the UID that is reserved for the Unix superuser. The Unix kernel disables most security checks when a process is being run by a user with the UID of 0.

Note

There is generally nothing special about any Unix account name. All Unix privileges are determined by the UID (and sometimes the group ID, or GID), and not directly by the account name. Thus, an account with name root and UID 1005 would have no special privileges, but an account named mortimer with UID 0 would be a superuser.

In general, you should avoid creating users with a UID of 0 other than root, and you should avoid using the name root for a regular user account. In this book, we will use the terms “root” and “superuser” interchangeably to mean a UID of 0.

Unix keeps the mapping between usernames and UIDs in the file /etc/passwd. Each user’s UID is stored in the field after the one containing the user’s encrypted password. For example, consider the sample /etc/passwd entry presented in Chapter 4:

rachel:x:181:181:Rachel Cohen:/u/rachel:/bin/ksh

In this example, Rachel’s username is rachel and her UID is 181.

The UID is the actual information that the operating system uses to identify the user; usernames are provided merely as a convenience for humans. If two users are assigned the same UID, Unix views them as the same user, even if they have different usernames and passwords. Two users with the same UID can freely read and delete each other’s files and can kill each other’s running programs. Giving two users the same UID is almost always a bad idea; it is better to create multiple users and put them in the same group, as we will see later.

Conversely, files can be owned by a UID that is not listed in /etc/passwd as having an associated username. This is also a bad idea. If a user is added to /etc/passwd in the future with that UID, that user will suddenly become the owner of the files.

Every Unix user belongs to one or more groups. As with user accounts, groups have both a group name and a group identification number (GID). GID values are also historically 16-bit integers, but many systems now use 32-bit integers for these, too.

As the name implies, Unix groups are used to group users together. As with usernames, group names and numbers are assigned by the system administrator when each user’s account is created. Groups can be used by the system administrator to designate sets of users who are allowed to read, write, and/or execute specific files, directories, or devices.

Each user belongs to a primary group that is stored in the /etc/passwd file. The GID of the user’s primary group follows the user’s UID. Historically, every Unix user was placed in the group users, which had a GID of 100. These days, however, most Unix sites place each account in its own group. This results in decreased sharing but somewhat greater security.[51]

Consider, again, our /etc/passwd example:

rachel:x:181:181:Rachel Cohen:/u/rachel:/bin/ksh

In this example, Rachel’s primary GID is 181.

Groups provide a handy mechanism for treating a number of users in a certain way. For example, you might want to set up a group for a team of students working on a project so that students in the group, but nobody else, can read and modify the team’s files.

Groups can also be used to restrict access to sensitive information or specially licensed applications to a particular set of users: for example, many Unix computers are set up so that only users who belong to the kmem group can examine the operating system’s kernel memory. The operator group is commonly used to allow only specific users to run the tape backup system, which may have “read” access to the system’s raw disk devices. And a sources group might be limited to people who have signed nondisclosure forms so they can view the source code for particular software.

Tip

Some special versions of Unix support mandatory access controls (MAC), which have controls based on data labeling instead of, or in addition to, the traditional Unix discretionary access controls (DAC). MAC-based systems do not use traditional Unix groups. Instead, the GID values and the /etc/group file may be used to specify security access control labeling or to point to capability lists. If you are using one of these systems, you should consult the vendor documentation to ascertain what the actual format and use of these values might be.

The /etc/group file contains the database that lists every group on your computer and its corresponding GID. Its format is similar to the format used by the /etc/passwd file.[52]

Here is a sample /etc/group file that defines six groups: wheel, http, vision, startrek, rachel, and users:

wheel:*:0:root,rachel http:*:10:http users:*:100: vision:*:101:keith,arlin,janice startrek:*:102:janice,karen,arlin rachel:*:181:

The first line of this file defines the wheel group. The fields are explained in Table 5-1.

Table 5-1. The first line of the example /etc/group file

|

Field contents |

Description |

|---|---|

|

|

Group name |

|

* |

Group’s “password” (described later) |

|

0 |

Group’s GID |

|

|

List of the users who are in the group |

Most versions of Unix use the wheel group as the list of all of the computer’s system administrators (in this case, rachel and the root user are the only members). On some systems, the group has a GID of 0; on other systems, the group has a GID of 10. Unlike a UID of 0, a GID of 0 is usually not significant. However, the name wheel is very significant: on many systems the use of the su command to invoke superuser privileges is restricted to users who are members of a group named wheel.

The second line of this file defines the http group. There is one member in the http group—the http user.

The third line defines the users group. The users group does not explicitly list any users; on some systems, each user is placed into this group by default through his individual entry in the /etc/passwd file.

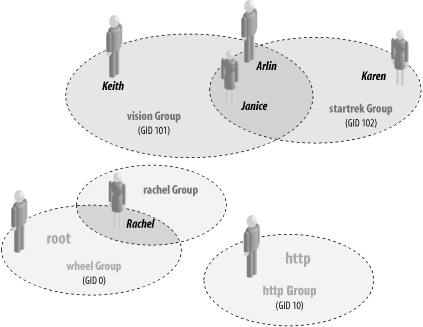

The fourth and fifth lines define two groups of users. The vision group includes the users keith, arlin, and janice. The startrek group contains the users janice, karen, and arlin. Notice that the order in which the usernames are listed on each line is not important. (This group is depicted graphically in Figure 5-1.)

Finally, the sixth line defines a group for the user rachel.

Remember that the users mentioned in the /etc/group file are in these groups in addition to the groups mentioned as their primary groups in the file /etc/passwd. For example, Rachel is in the rachel group even though she does not appear in that group in the file /etc/group because her primary group number is 181. On most versions of Unix, you can use the groups command to list which groups that you are currently in:

% groups

rachel wheel

%The groups command can also take a username as an argument:

% groups arlin

vision, startrek

%When a user logs into the Unix system, the /bin/login program scans the /etc/passwd and /etc/group files, determines which groups the user is a member of, and adds them to the user’s user structure using the setgroups( ) system call.[53]

Some versions of Unix are equipped with an id command that offers more detailed UIDs, GIDs, and group lists:

%iduid=181(rachel) gid=181(rachel) groups=181(rachel), 0(wheel) %id rootuid=0(root) gid=0(wheel) groups=0(wheel),1(bin),15(shadow),65534(nogroup)

Figure 5-1 illustrates how users can be included in multiple groups.

Tip

It is not necessary for there to be an entry in the /etc/group file for a group to exist! As with UIDs and account names, Unix actually uses only the integer part of the GID for all settings and permissions. The name in the /etc/group file is simply a convenience for the users—a means of associating a mnemonic with the GID value.

[49] lp stands for line printer, although these days most people seem to be using laser printers.

[50] Technically, it is a simple relational database.

[51] The advantage of assigning each user his own group is that it allows users to have a unified umask of 007 in all instances. When users wish to restrict access of a file or directory to themselves, they leave the group set to their individual group. When they wish to open the file or directory to members of their workgroup or project, all they need to do is to change the file’s or directory’s group accordingly.

[52] As with the password file, if your site is running NIS, NIS+, or DCE, the /etc/group file may be incomplete or missing. See the discussion in Section 4.3.1 in Chapter 4.

[53] If you are on a system that uses NIS, NIS+, or some other system for managing user accounts throughout a network, these network databases will be referenced as well. For more information, see Chapter 19.