As the name implies, filesystems store information in files. A file is a block of information that is given a single name and can be acted upon with a single operation. For example, on a Unix system this block of data can be copied with the cp command and erased with the rm command.[62] Contiguous portions of the data can be read or written under program control.

In addition to the data that is stored in files, filesystems store a second kind of data called metadata, which is information about files. The metadata in a typical filesystem includes the names of the files, the date that the files were created, and information that is used to group the files into manageable categories.

The original Unix File System (UFS) pioneered many of the concepts that are widespread in filesystems today. UFS allowed files to contain any number of bytes, rather than forcing the file to be blocked into “records.” UFS was also one of the very first tree-structured filesystems: instead of having several drives or volumes, each with its own set of directories, UFS introduced the concept of having a master directory called the root.[63] This directory, in turn, can contain other directories or files.

Unix and the UFS introduced the concept that “everything is a file”—logical devices (such as /dev/tty), sockets, and other sorts of operating system structures were represented in a filesystem by special files, rather than given different naming conventions and semantics.

Finally, Unix introduced a simple set of function calls (an API) for accessing the contents of files: open( ) for opening a file, read( ) for reading a file’s contents, close( ) for closing the file, and so on. This API and its associated behavior are part of the POSIX standard specification.

Personnel at the University of California at Berkeley created an improved version of UFS that they named the Fast File System (FFS). Besides being faster (and somewhat more robust), FFS had two important innovations: it allowed for long file names and it introduced the concept of a symbolic link—a file that could point to another file. FFS was such an improvement over the original UFS that AT&T eventually abandoned its filesystem in favor of FFS.

Unix files are an unstructured collection of zero or more bytes of information. A file might contain an email message, a word processor document, an image, or anything else that can be represented as a stream of digital information. In principle, files can be any size, from zero bits to multiple terabytes of data.

Most of the information that you store on a Unix system is stored as the contents of files. Even database systems such as Oracle or MySQL ultimately store their information as the contents of files.

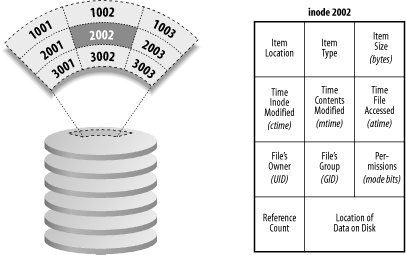

For each set of file contents in the filesystem, Unix stores administrative information in a structure known as an inode (index node). Inodes reside on disk and do not have names. Instead, they have indices (numbers) indicating their positions in the array of inodes on each logical disk.

Each inode on a Unix system contains:

The location of the item’s contents on the disk

The item’s type (e.g., file, directory, symbolic link)

The item’s size, in bytes, if applicable

The time the file’s inode was last modified, typically at file creation (the ctime )

The time the file’s contents were last modified (the mtime )

The time the file was last accessed (the atime ) for read ( ), exec ( ), etc.

A reference count, which is the number of names the file has

The file’s mode bits (also called file permissions or permission bits)

The last three pieces of information, stored for each item and coupled with UID/GID information about executing processes, are the fundamental data that Unix uses for practically all local operating system security.

Other information can also be stored in the inode, depending on the particular version of Unix involved, and the form of filesystem being used.

Figure 6-1 shows how information is stored in an inode.

As a user of a modern computer system, you probably think of a directory (also known as a folder) as a container that can hold one or more files and other directories. When you look at a directory you see a list of files, the size of each file, and other kinds of information.

Unix directories are much simpler than this. A Unix directory is nothing more than a list of names and inode numbers. These names are the names of files, directories, and other objects stored in the filesystem.

A name in a directory can consist of any string of any characters with the exception of a “/” character and the “null” character (usually a zero byte).[64] There is a limit to the length of these strings, but it is usually quite long: 255 characters or longer on most modern versions of Unix. Older AT&T versions limited names to 14 characters or less.

Each name can contain control characters, line feeds, and other characters. This flexibility can have some interesting implications for security, which we’ll discuss later in this and other chapters.

Associated with each name is a numeric pointer that is actually an index on disk for an inode. An inode contains information about an individual entry in the filesystem; these contents are described in the next section.

Nothing else is contained in the directory other than names and inode numbers. No protection information is stored there, nor owner names, nor data. This information is all stored with the inode itself. The directory is a very simple relational database that maps names to inode numbers.

Unix places no restrictions on how many names can point to the same inode. A directory may have 2, 5, or 50 names that each have the same inode number. In like manner, several directories may have names that associate to the same inode. These names are known as links or hard links to the file (another kind of link, the symbolic link, is discussed later).

The ability to have hard links is peculiar for the Unix environment, and “peculiar” is certainly a good word for describing how hard links behave. No matter which hard link was created first, all links to a file are equal. This is often a confusing idea for beginning users.

Because of the way that links are implemented, you don’t actually delete a file with commands such as rm . Instead, you unlink the name—you sever the connection between the filename in a directory and the inode number. If another link still exists, the file will continue to exist on disk. After the last link is removed, and the file is closed, the kernel will normally reclaim the storage because there is no longer a method for a user to access it. Internally, each inode maintains a reference count, which is the count of how many filenames are linked to the inode. The rm command unlinks a filename and reduces the inode’s reference count. When the reference count reaches zero, the file is no longer accessible by name.

Every directory has two special names that are always present unless the filesystem is damaged. One entry is "." (dot), and this is associated with the inode for the directory itself; it is self-referential. The second entry is for ".." (dot-dot), which points to the “parent” of this directory—the directory next closest to the root in the tree-structured filesystem. Because the root directory does not have a parent directory, in the root directory the “.” directory and the “..” directories are links to the same directory—the root directory.

You can create a hard link to a file with the Unix ln command. But you cannot create a hard link to a directory—only the kernel can do this.[65] This is how the kernel creates the “..” directory. You can, however, create symbolic links to directories.

The virtual filesystem interface allows the Unix operating system to interoperate with multiple filesystems at the same time. The interface is sometimes called a vnode interface because it defines a set of operations that the Unix kernel can perform on virtual nodes, in contrast with the physical inodes of the UFS.

The original virtual filesystem interface was developed by Sun Microsystems to support its Network Filesystem (NFS). Since then, this interface has been extended and adapted for many different filesystems.

Modern Unix systems come with support for many filesystems, as is shown in Table 6-1. Unfortunately, many of these systems have semantics that are slightly different from the POSIX standard. This can cause security problems for programs using these filesystems if their developers were not aware of the differing semantics.

Table 6-1. Filesystems available on Unix systems

|

Filesystem |

Originally developed for |

Divergence from POSIX standard |

|---|---|---|

|

Unix |

None | |

|

CD-ROMs |

No support for file ownership or permissions | |

|

Microsoft DOS |

No support for file ownership or permissions; preserves but ignores the case of letters in filenames | |

|

Microsoft Windows NT |

Preserves but ignores the case of letters in filenames | |

|

Linux |

None | |

|

Macintosh |

Preserves but ignores the case of files; allows additional file contents to be stored in a “resource fork” |

Every item with a name in the filesystem can be specified with a pathname. The word pathname is appropriate because a pathname represents the path to the entry from the root of the filesystem. By following this path, the system can find the inode of the referenced entry.

Pathnames can be absolute or relative. Absolute pathnames always start at the root, and thus always begin with a “/ “, representing the root directory. Thus, a pathname such as /homes/mortimer/bin/crashme represents a pathname to an item starting at the root directory.

A relative pathname always starts interpretation from the current directory of the process referencing the item. This concept implies that every process has associated with it a current directory . Each process inherits its current directory from a parent process after a fork (see Appendix B). The current directory is initialized at login from the sixth field of the user record in the /etc/passwd file: the home directory. The current directory is then updated every time the process performs a change-directory operation (chdir or cd ). Relative pathnames also imply that the current directory is at the front of the given pathname. Thus, after executing the command cd /usr, the relative pathname lib/makekey would actually be referencing the pathname /usr/lib/makekey. Note that any pathname that doesn’t start with a “/” must be relative.

[62] Actually, as we’ll see later, rm only makes a file inaccessible by name; it doesn’t necessarily remove the file’s data.

[63] This is where the root user (superuser) name originates: the owner of the root of the filesystem. In older Unix systems, root’s home directory was /. Modern systems typically give root a more private home directory, such as /root.

[64] Some versions of Unix may further restrict the characters that can be used in filenames and directory names.

[65] Actually, if you are a high wizard of Unix and edit the disk directly, or perform other kinds of highly risky and privileged operations, you can create links to directories. However, this breaks many programs, introduces security problems, and can confuse your users when they encounter these links. Thus, you should not attempt this.