Copyright © 2018 Packt Publishing

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles or reviews.

Every effort has been made in the preparation of this book to ensure the accuracy of the information presented. However, the information contained in this book is sold without warranty, either express or implied. Neither the author, nor Packt Publishing or its dealers and distributors, will be held liable for any damages caused or alleged to have been caused directly or indirectly by this book.

Packt Publishing has endeavored to provide trademark information about all of the companies and products mentioned in this book by the appropriate use of capitals. However, Packt Publishing cannot guarantee the accuracy of this information.

Commissioning Editor: Kunal Chaudhari

Acquisition Editor: Karan Gupta

Content Development Editor: Flavian Vaz

Technical Editor: Diksha Wakode

Copy Editor: Safis Editing

Project Coordinator: Sheejal Shah

Proofreader: Safis Editing

Indexer: Aishwarya Gangawane

Graphics: Jason Monteiro

Production Coordinator: Shraddha Falebhai

First published: September 2018

Production reference: 1290918

Published by Packt Publishing Ltd.

Livery Place

35 Livery Street

Birmingham

B3 2PB, UK.

ISBN 978-1-78847-732-1

Mapt is an online digital library that gives you full access to over 5,000 books and videos, as well as industry leading tools to help you plan your personal development and advance your career. For more information, please visit our website.

Spend less time learning and more time coding with practical eBooks and Videos from over 4,000 industry professionals

Improve your learning with Skill Plans built especially for you

Get a free eBook or video every month

Mapt is fully searchable

Copy and paste, print, and bookmark content

Did you know that Packt offers eBook versions of every book published, with PDF and ePub files available? You can upgrade to the eBook version at www.packt.com and as a print book customer, you are entitled to a discount on the eBook copy. Get in touch with us at customercare@packtpub.com for more details.

At www.PacktPub.com, you can also read a collection of free technical articles, sign up for a range of free newsletters, and receive exclusive discounts and offers on Packt books and eBooks.

Daniel Li is a full-stack JavaScript developer at Nexmo. Previously, he was also the Managing Director of Brew, a digital agency in Hong Kong that specializes in MeteorJS.

A proponent of knowledge-sharing and open source, Daniel has written over 100 blog posts and in-depth tutorials, helping hundreds of thousands of readers navigate the world of JavaScript and the web.

Federico Kereki is a Uruguayan systems engineer with a master's degree in education, and over 30 years' experience as a consultant, developer, professor, and writer.

He is a subject matter expert at Globant, and he has taught at Universidad de la República, Universidad ORT, and Universidad de la Empresa. He has written several articles for magazines and websites, a pair of booklets on computer security, and two books, Essential GWT and Mastering JavaScript Functional Programming.

He's currently writing a new book on JavaScript development for Packt Publishing.

If you're interested in becoming an author for Packt, please visit authors.packtpub.com and apply today. We have worked with thousands of developers and tech professionals, just like you, to help them share their insight with the global tech community. You can make a general application, apply for a specific hot topic that we are recruiting an author for, or submit your own idea.

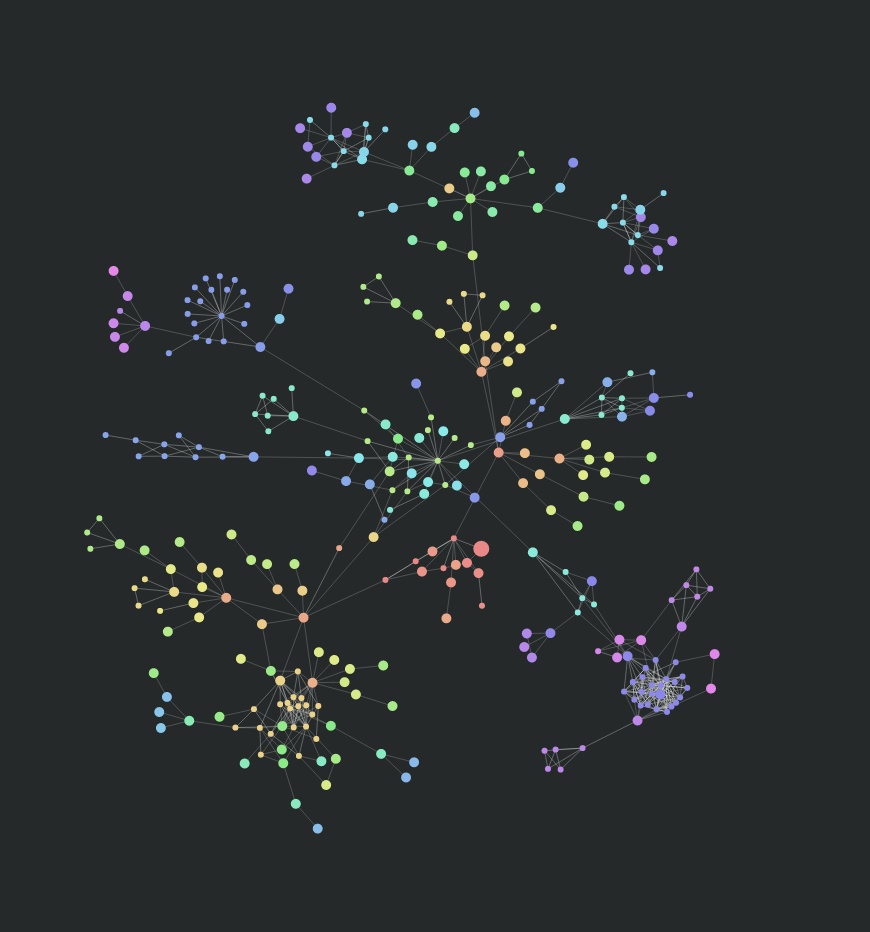

JavaScript Fatigue was a trendy term back in 2016, a time when new libraries and frameworks emerged on a daily basis. This promoted diversity, but also crippled developers with too many options. Even today, developers are expected to have experience working with build tools, linters, testing frameworks, assertion libraries, package managers, module loaders, module bundlers, routers, web servers, compilers, transpilers, static typecheckers, virtual DOM libraries, state management tools, CSS preprocessors and UI Frameworks (I've probably missed a few).

No wonder people find it difficult to get started, or even keep up, with JavaScript. Many have spent days learning a dozen different tools just to set up their project. And that's before they write a single line of code!

Nonetheless, this boom in diversity does bring tangible benefits—it pulls us away from opinionated frameworks and allows us to tailor our application as a composite of many smaller modules. Therefore, instead of bemoaning the state of the ecosystem, we should spend the time to learn each tool.

If that sounds like a tortuous undertaking, then this book will save you a lot of time.

Whilst most programming books today examine a single framework, library, or language in great detail, this book provides you with a solid foundation on a wide range of tools and practices commonly used in enterprise environments. Each of them contributes to building a reliable, production-ready application. In other words, we focus on breadth over depth.

We also value structure over chaos; as such, there's a heavy emphasis on establishing best practices, following processes, testing, infrastructure, and automation. If these words whet your appetite, then this book is perfect for you.

Traditionally, most tech companies followed a horizontal structure, where development, testing, and operations are separated into different departments. Since they are interdependent, every team can only work at the pace of the slowest team.

In recent years, however, we have seen a shift towards vertical teams. Vertical teams are formed based on project requirements, where each team is responsible for all stages of the process—from gathering requirements to deployment. This allows teams to take full ownership of the entire feature, as they become self-reliant and can move at their own pace. Consequently, many companies require their developers to command a broad skillset.

Therefore, this book is not just written for JavaScript developers who are eager to learn new tools, but for all developers who wish to stay relevant in today's job market.

Unlike online blogs and websites, physical books have a page limit. Consequently, we had to be rigorous in our choice of tools to include. In the end, we hand-selected tools and frameworks based on two criteria:

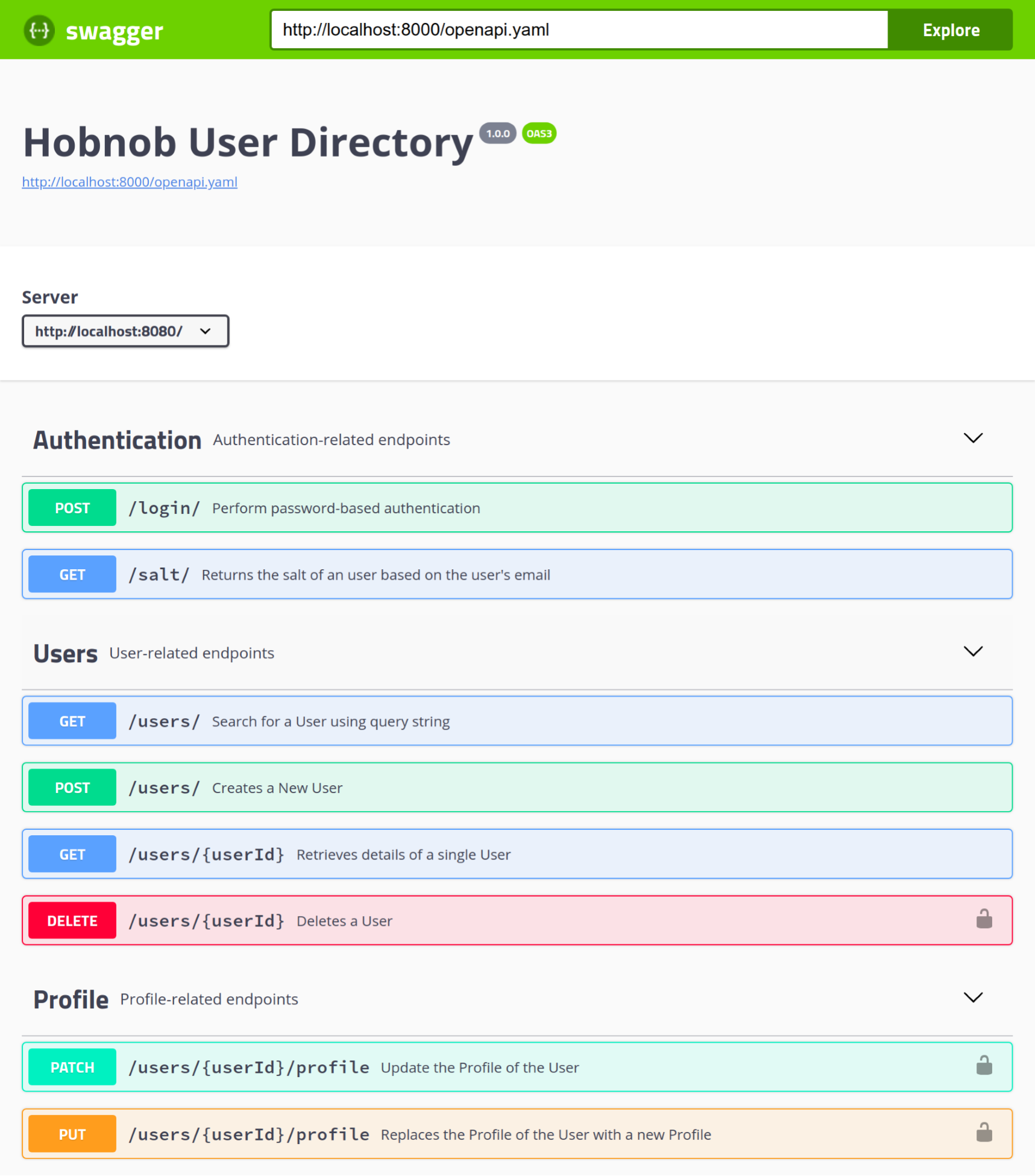

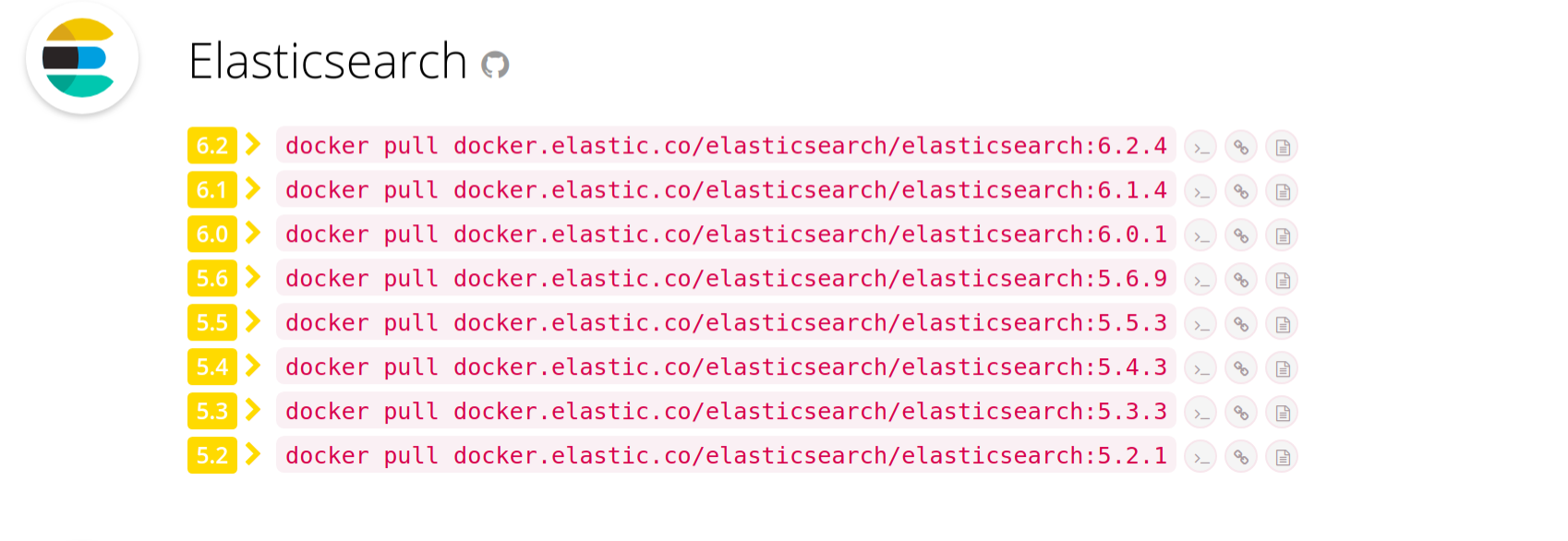

This narrowed down the list to these tools—Git, npm, yarn, Babel, ESLint, Cucumber, Mocha, Istanbul/NYC, Selenium, OpenAPI/Swagger, Express, Elasticsearch, React, Redux, Webpack, Travis, Jenkins, NGINX, Linux, PM2, Docker, and Kubernetes. We will utilize these tools to build a simple, but robust, user directory application that consists of a backend API and a frontend web user interface (UI).

This book is divided into five sections:

Chapter 1, The Importance of Good Code, explains the negative consequences of technical debt, and how implementing test-driven development (TDD) can mitigate this effect.

Chapter 2, The State of JavaScript, provides an abridged account of the evolution of the web application, from following a client-server model to single-page applications (SPAs), and the role JavaScript and Node.js play in that transition.

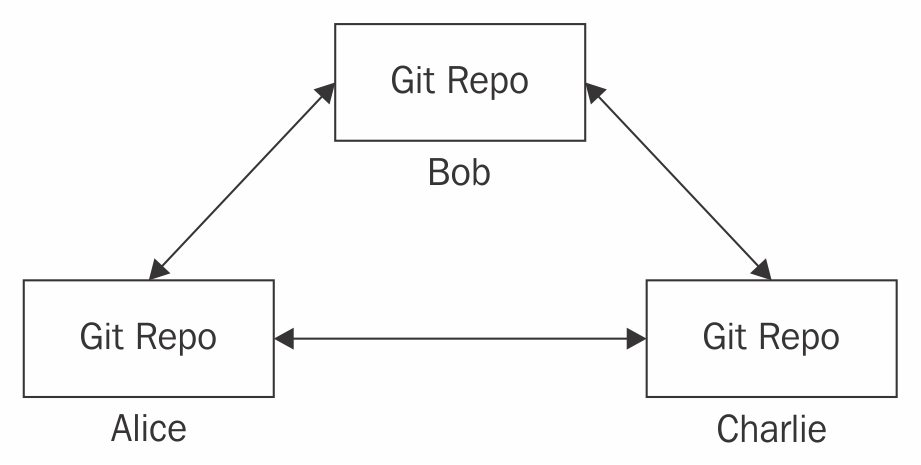

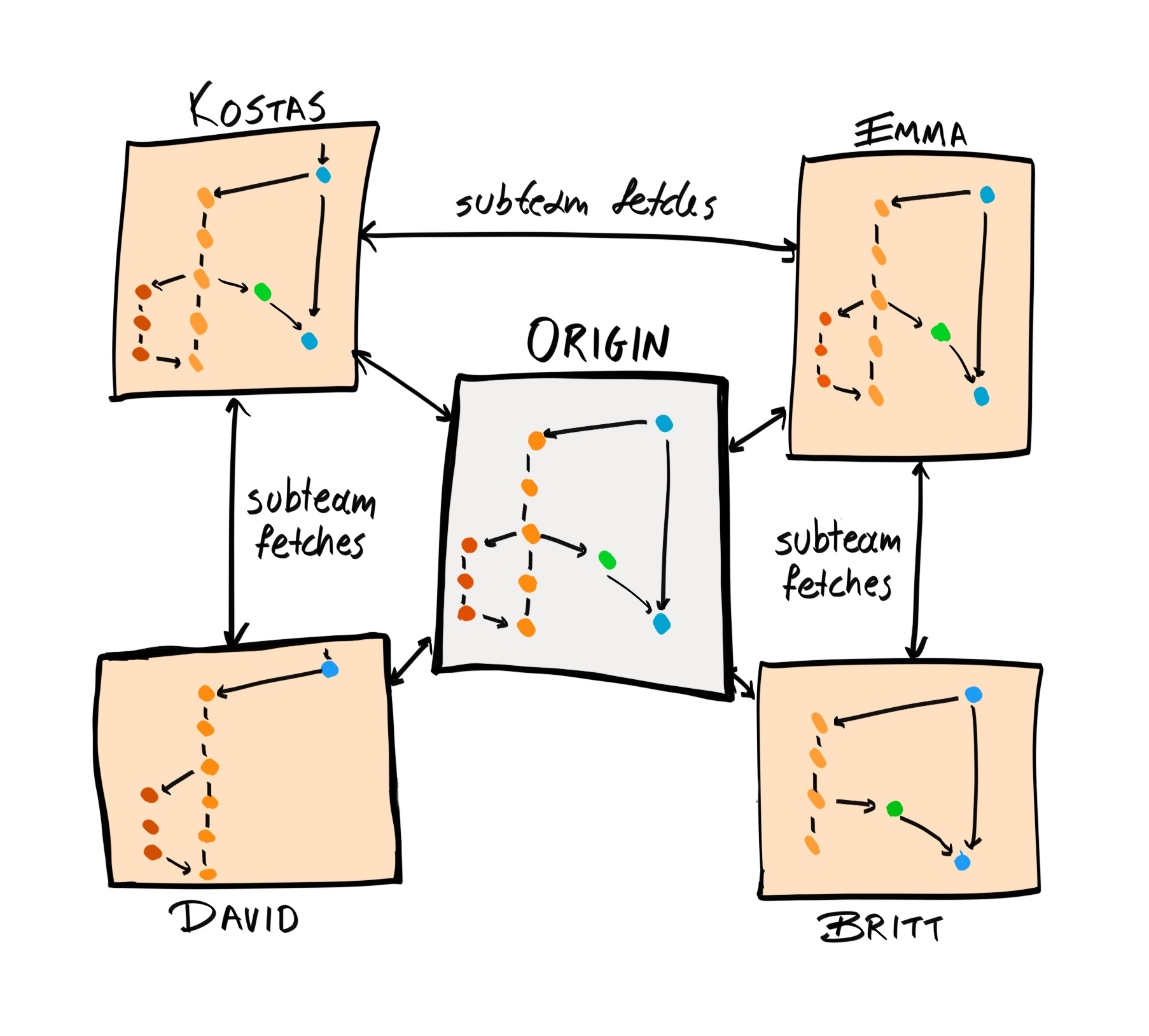

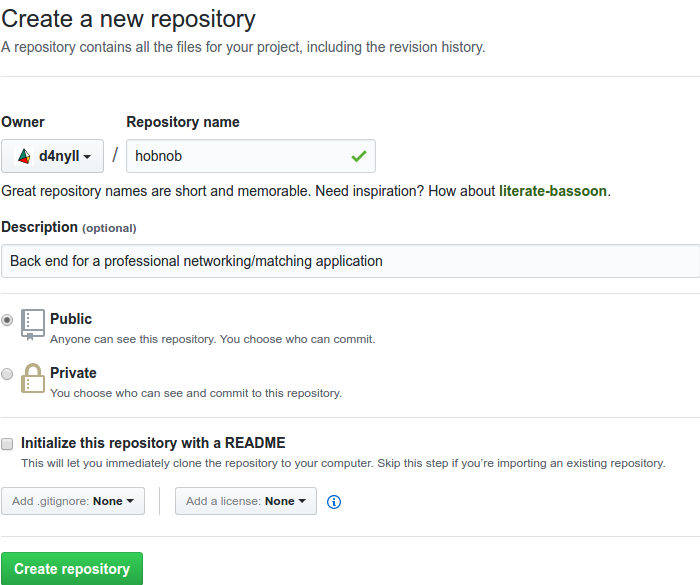

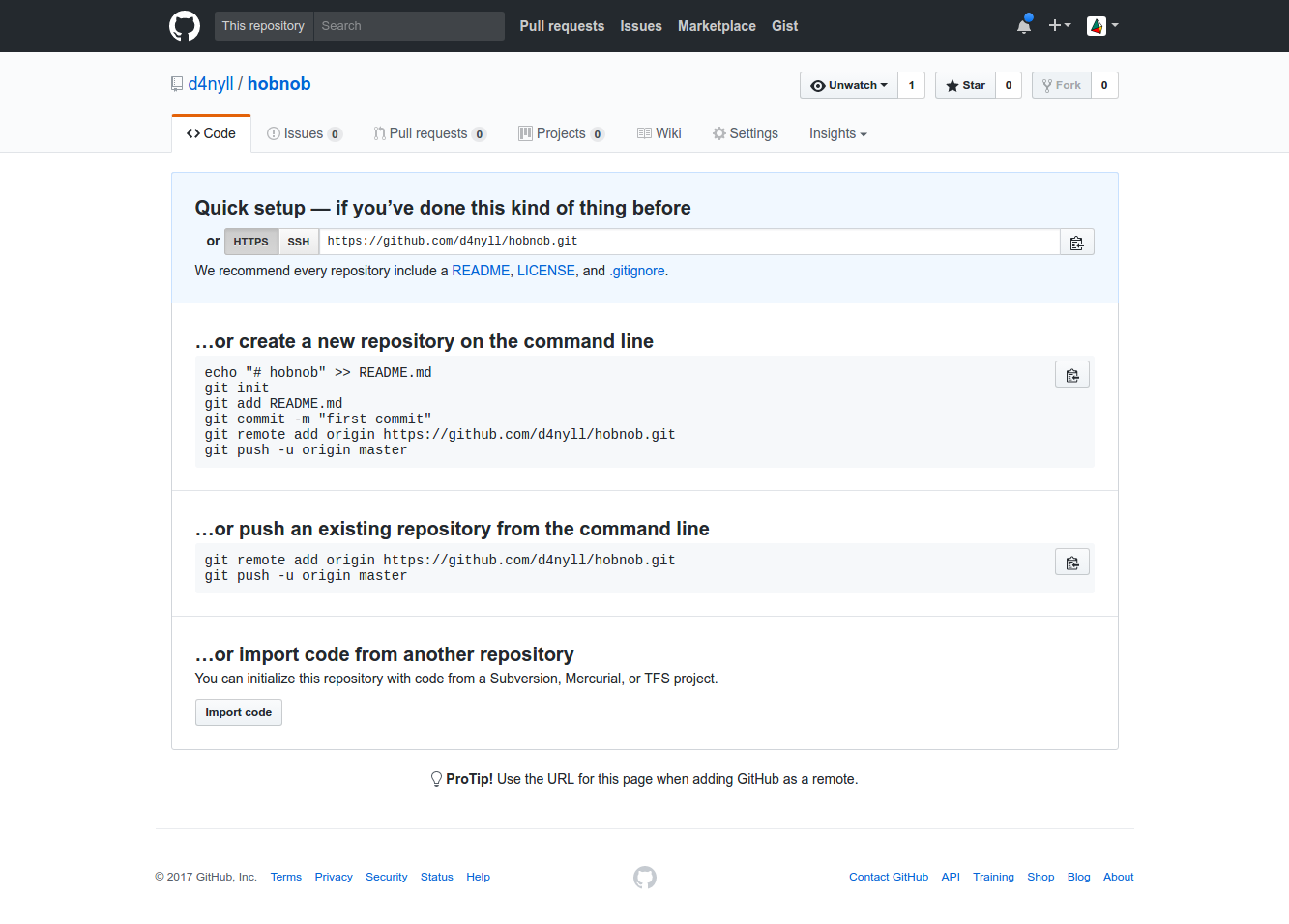

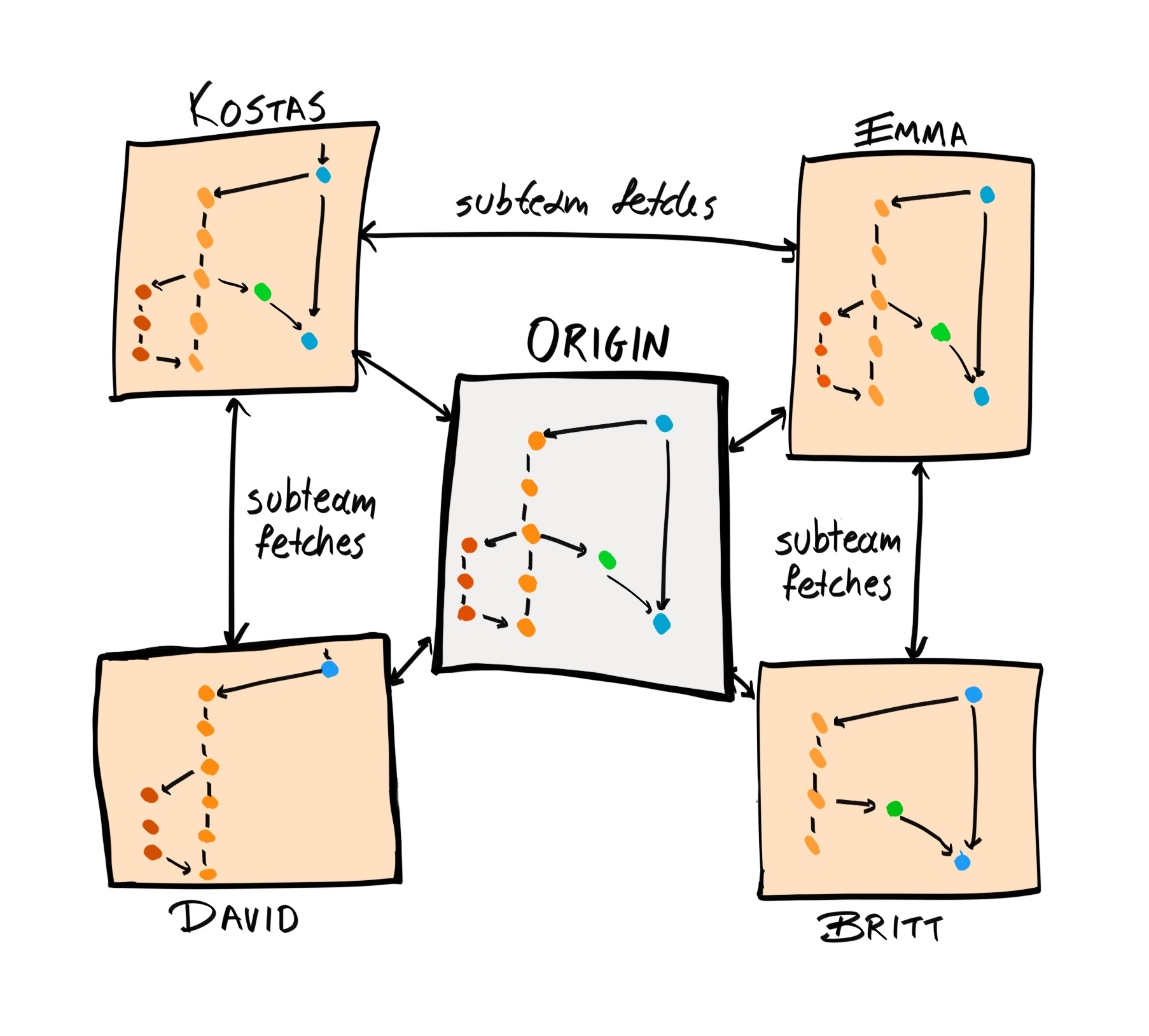

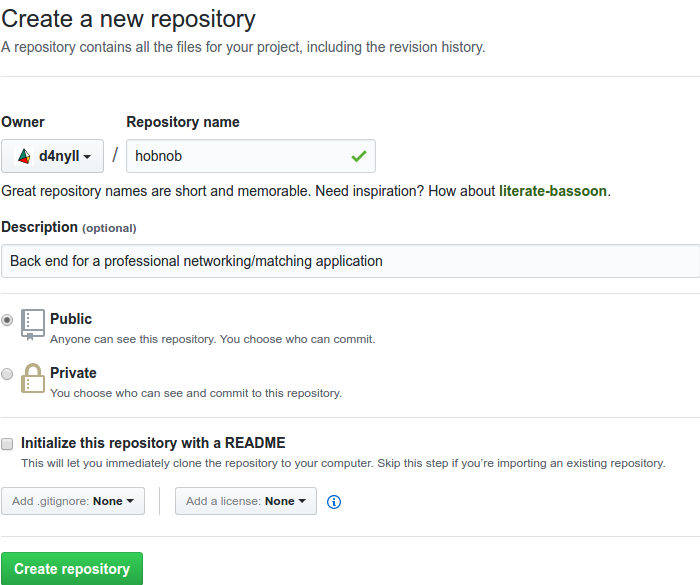

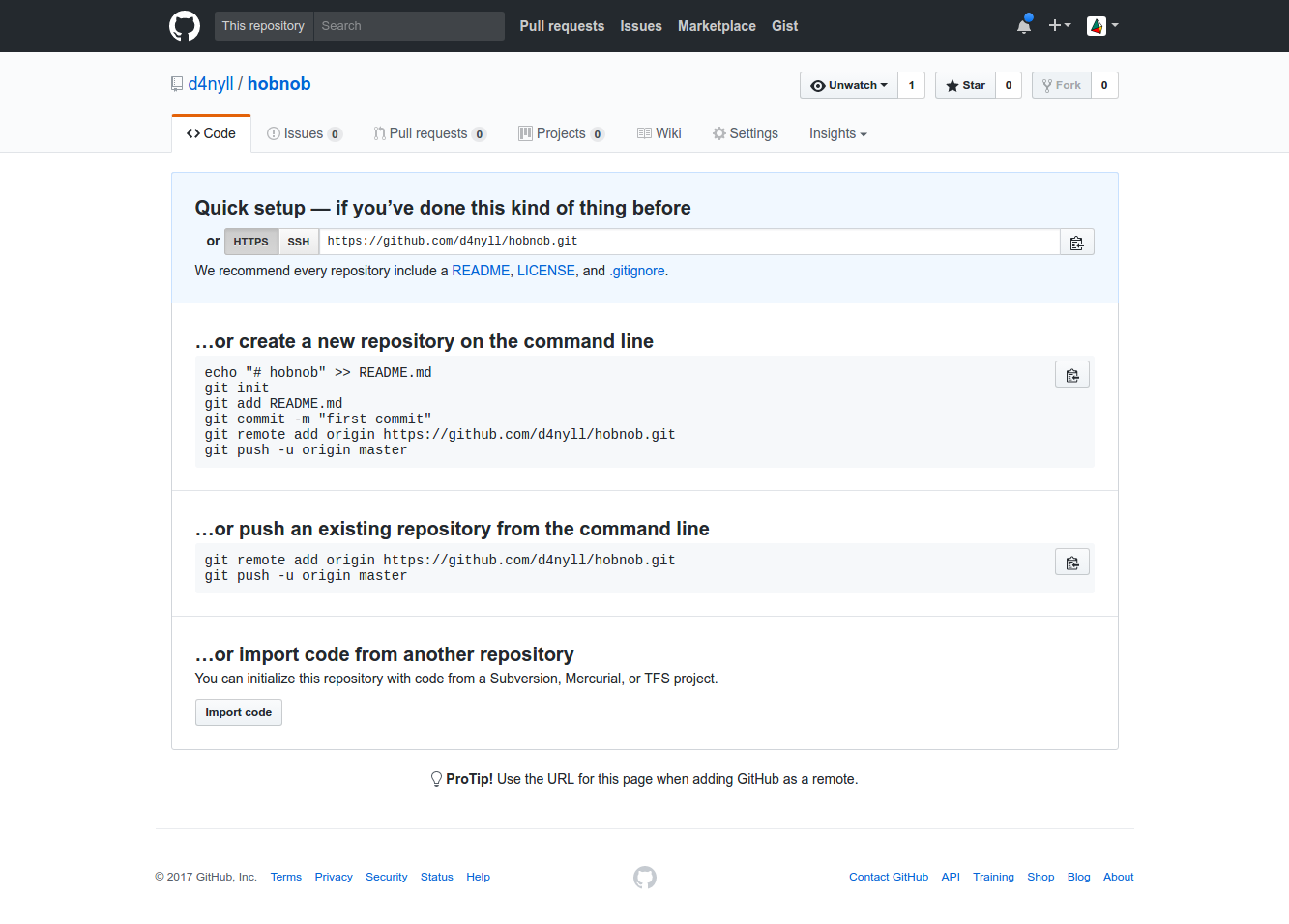

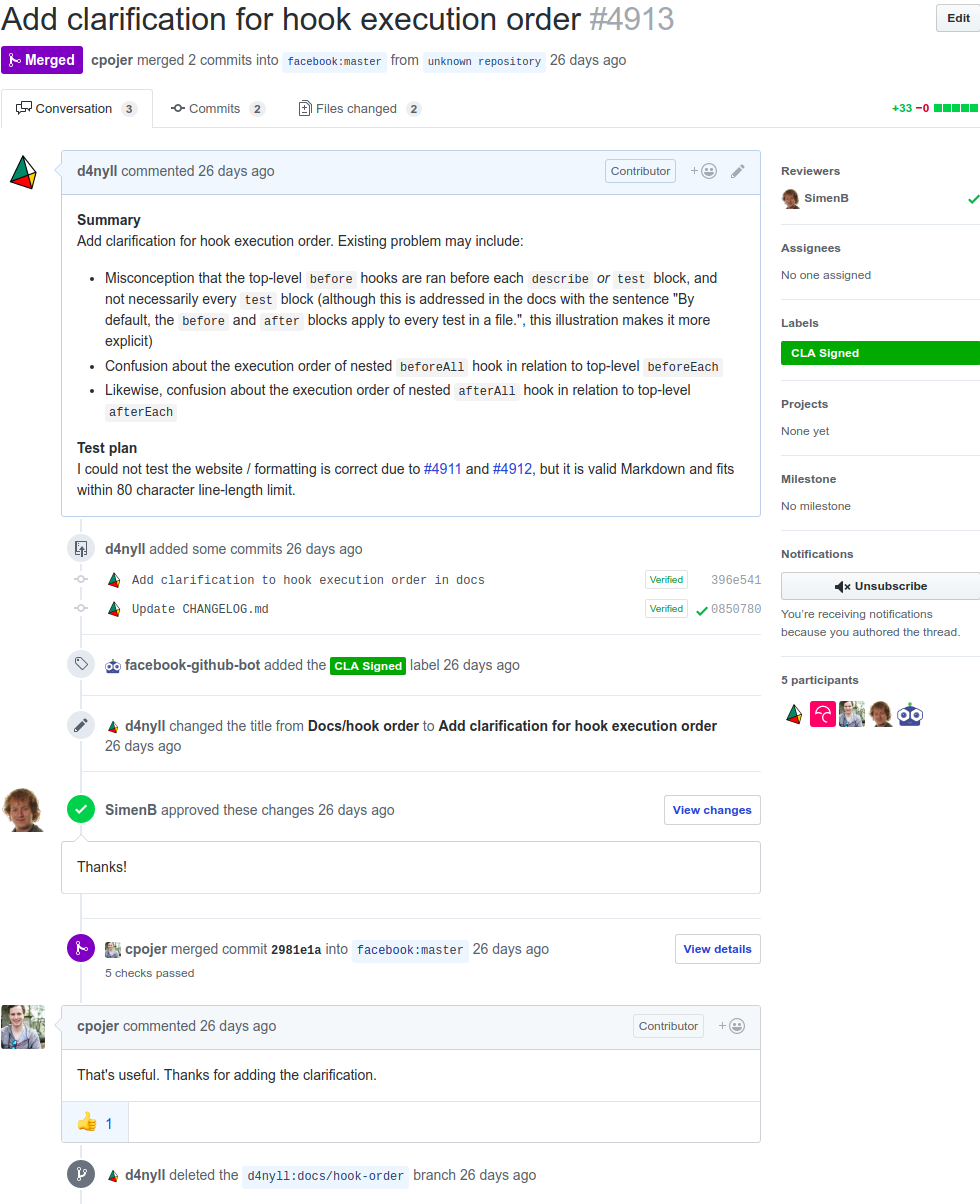

Chapter 3, Managing Version History with Git, introduces you to the concept of version control (VC). Specifically, we will learn how to work with Git, Git Flow, and GitHub.

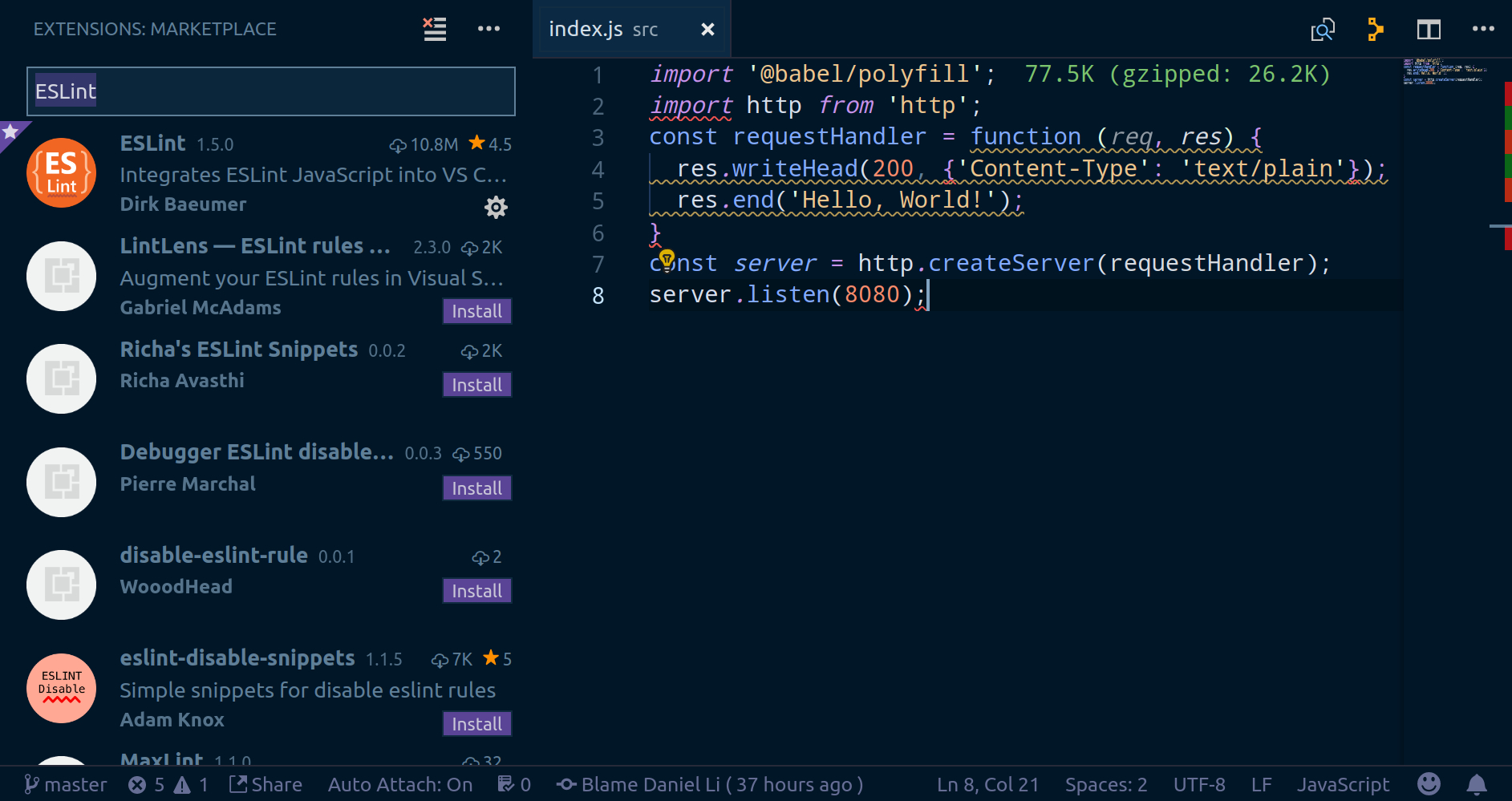

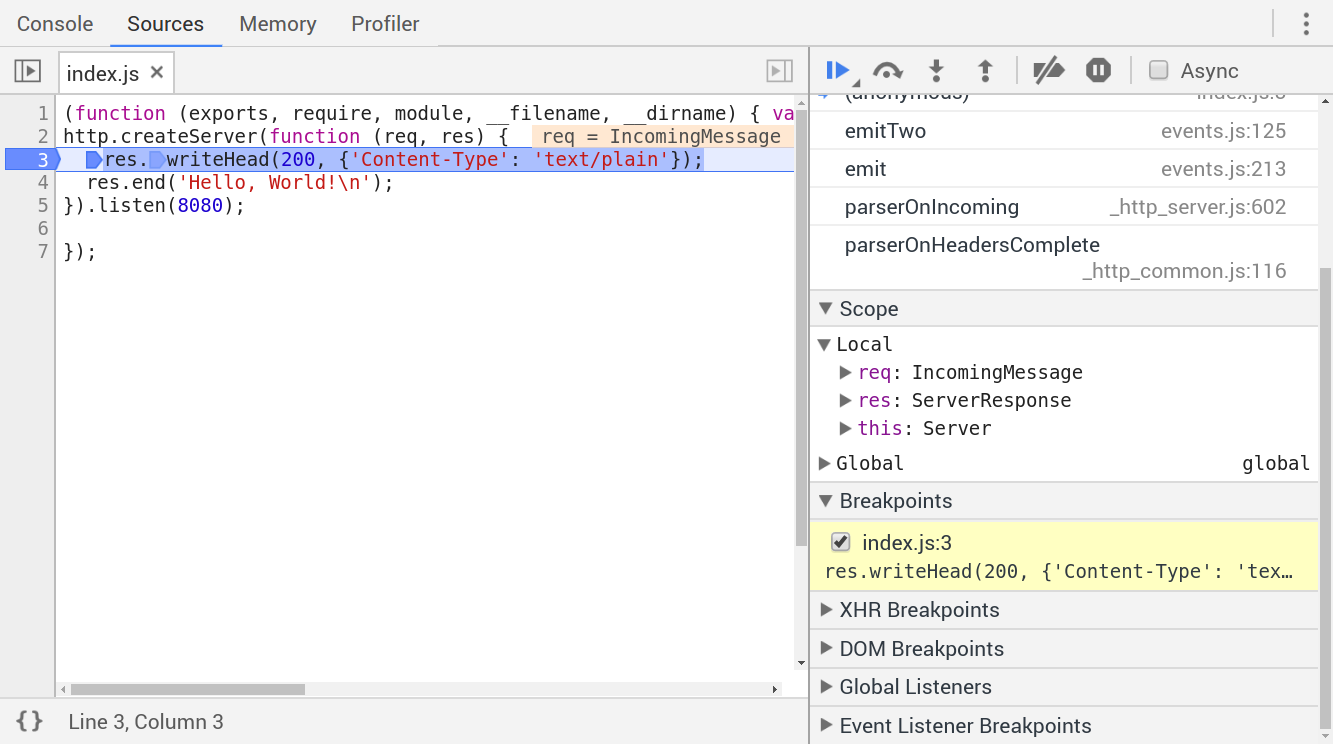

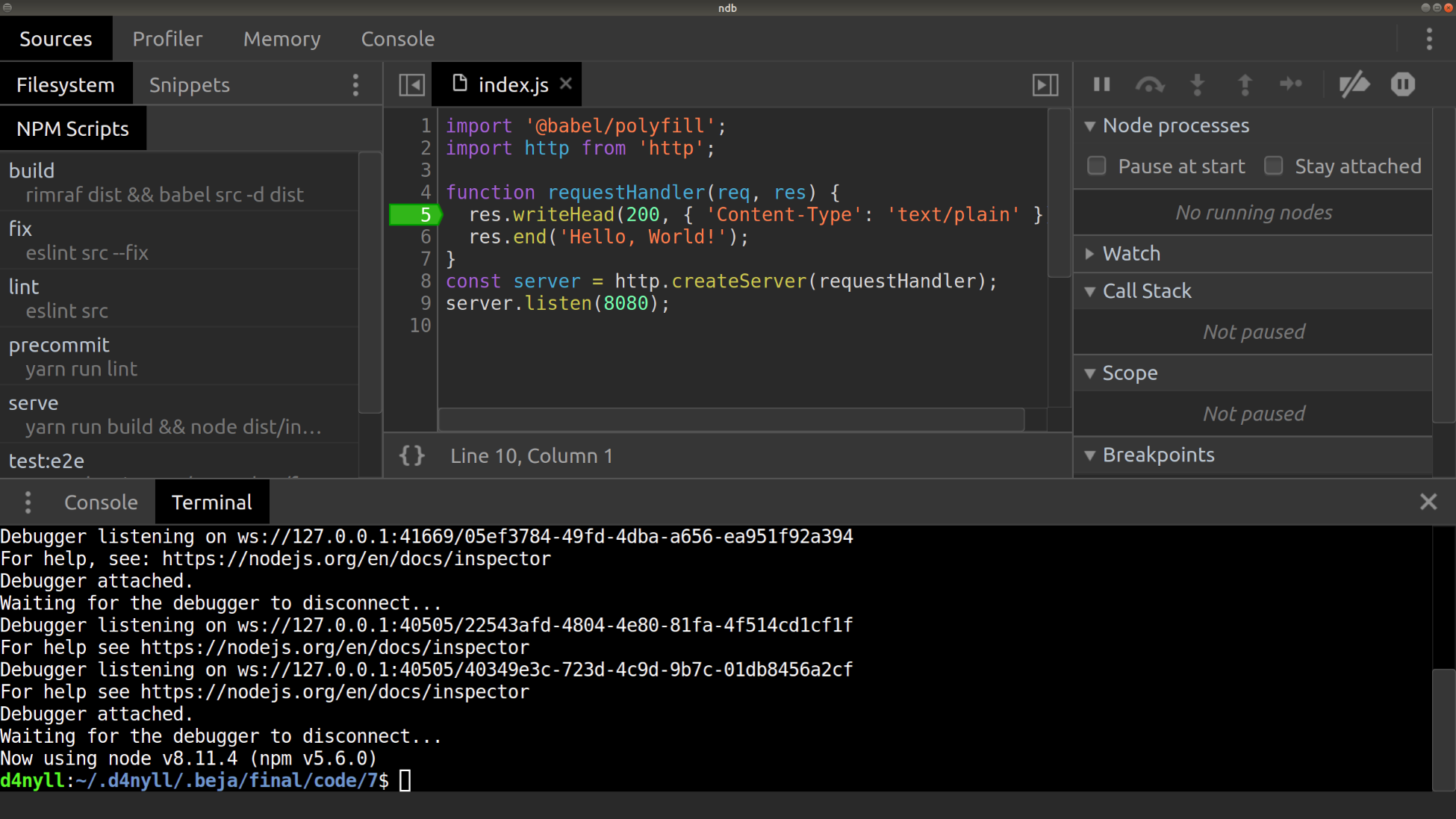

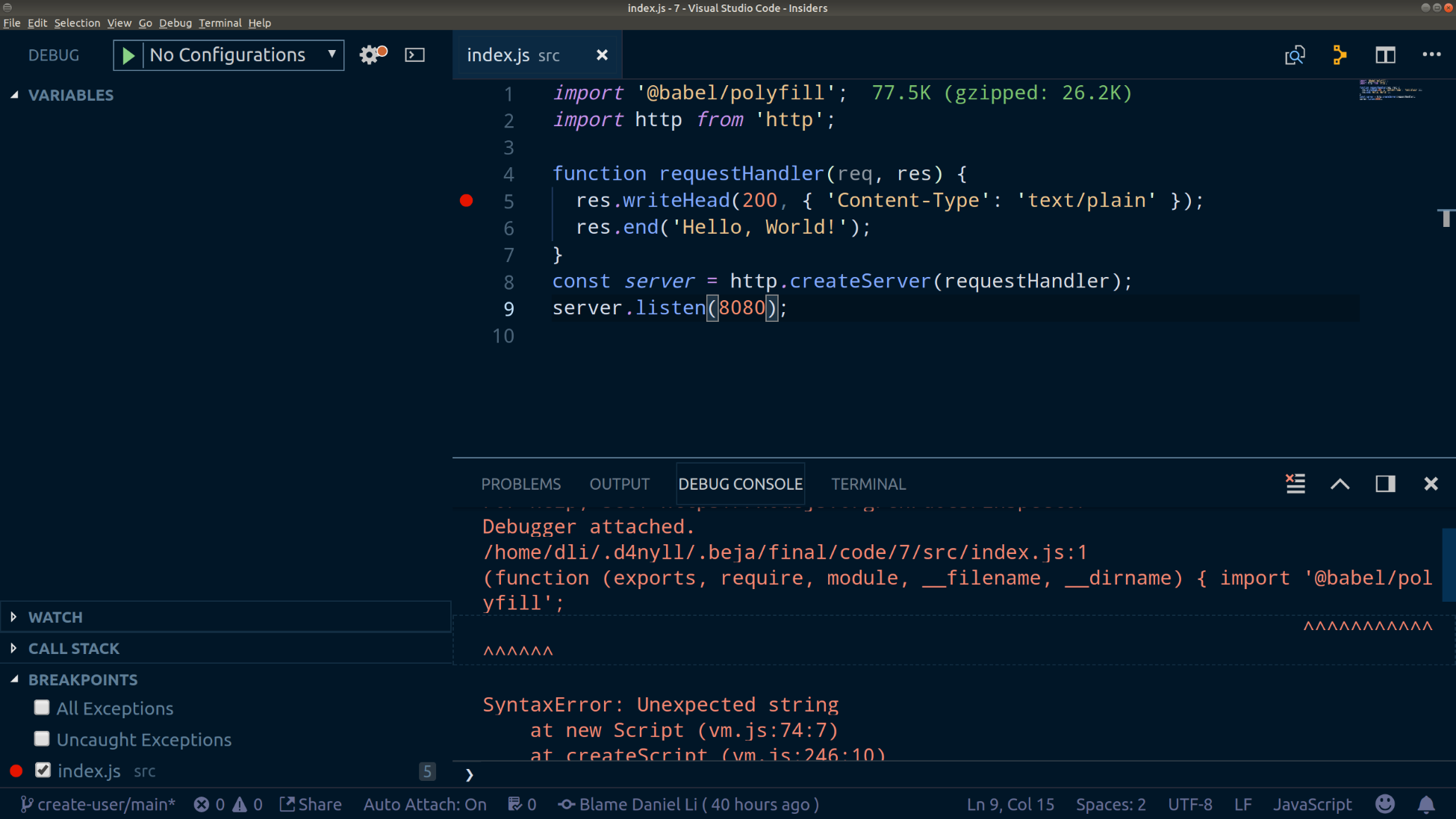

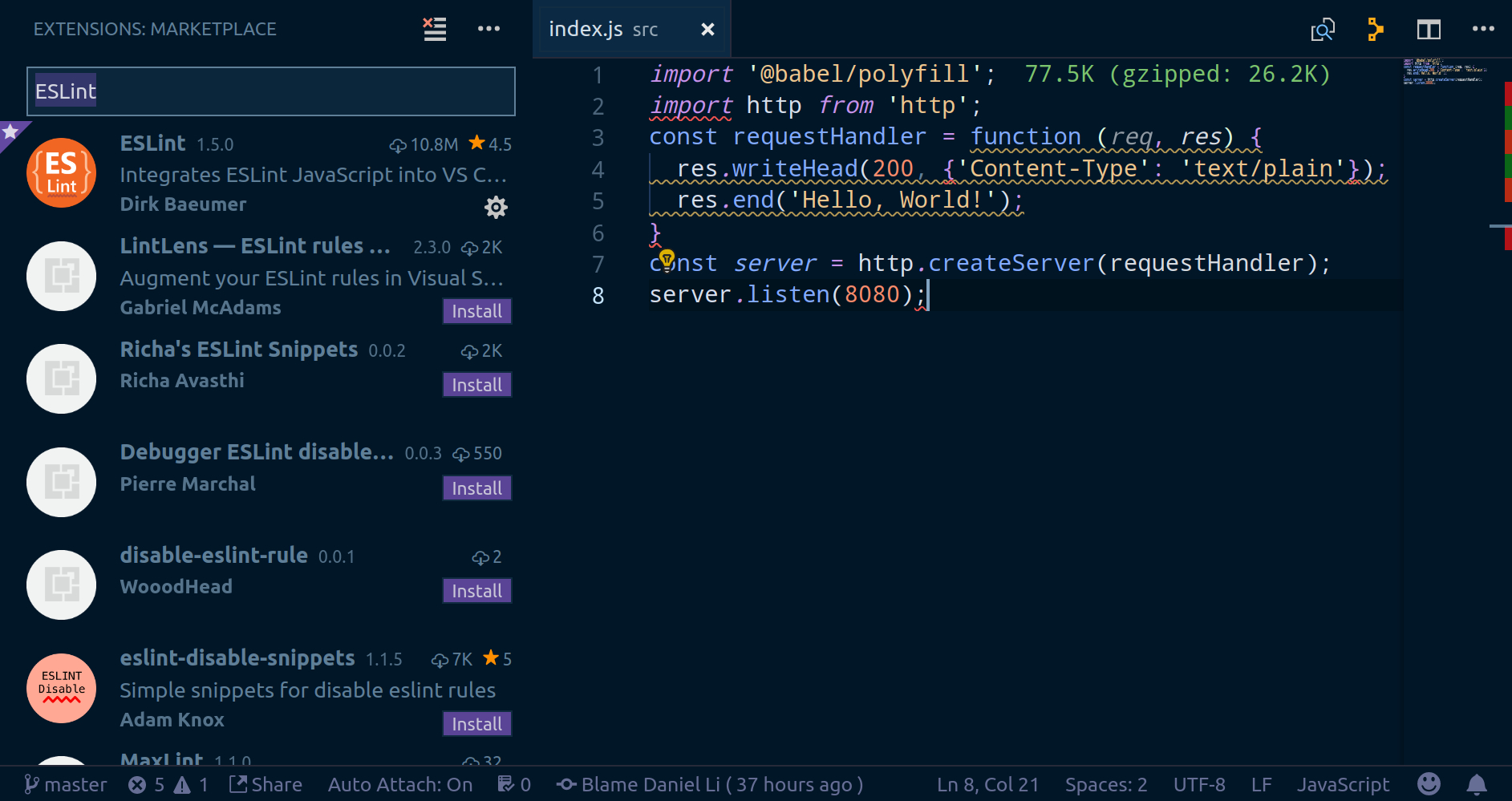

Chapter 4, Setting Up Development Tools, explains the different module formats in JavaScript, including CommonJS and ES6 modules. We'll also be setting up our local environment with tools such as nvm, yarn, Babel, nodemon, and ESLint.

Chapter 5, Writing End-to-End Tests, helps you practice TDD by teaching you how to write end-to-end (E2E) tests using Cucumber and Gherkin. We'll also migrate our API to Express as part of the refactoring step.

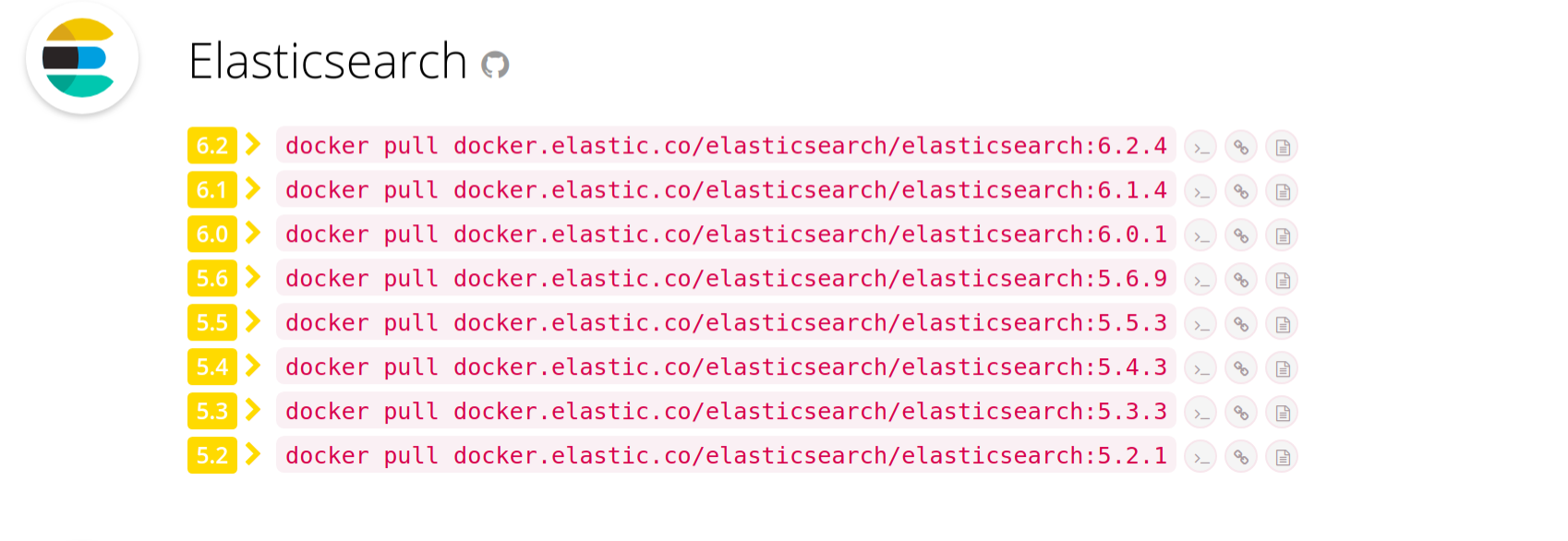

Chapter 6, Storing Data in Elasticsearch, continues our TDD journey as we persist our application data onto Elasticsearch, a NoSQL document store and search engine. Toward the end of the chapter, we'll also write some Bash scripts to streamline our testing process.

Chapter 7, Modularizing Our Code, will break our application down into smaller modules. We will also integrate JSON Schema and Ajv in our implementation of the validation module.

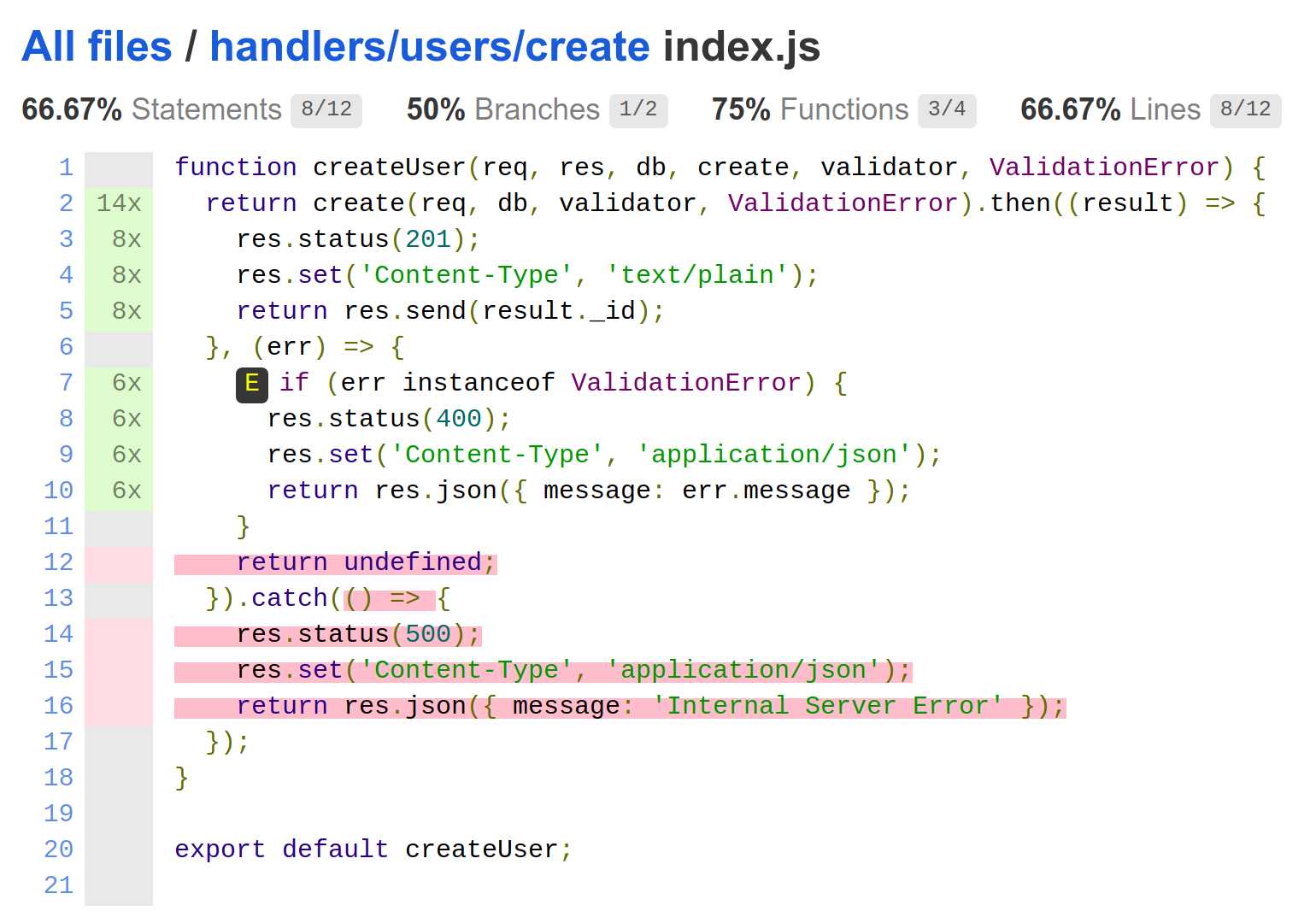

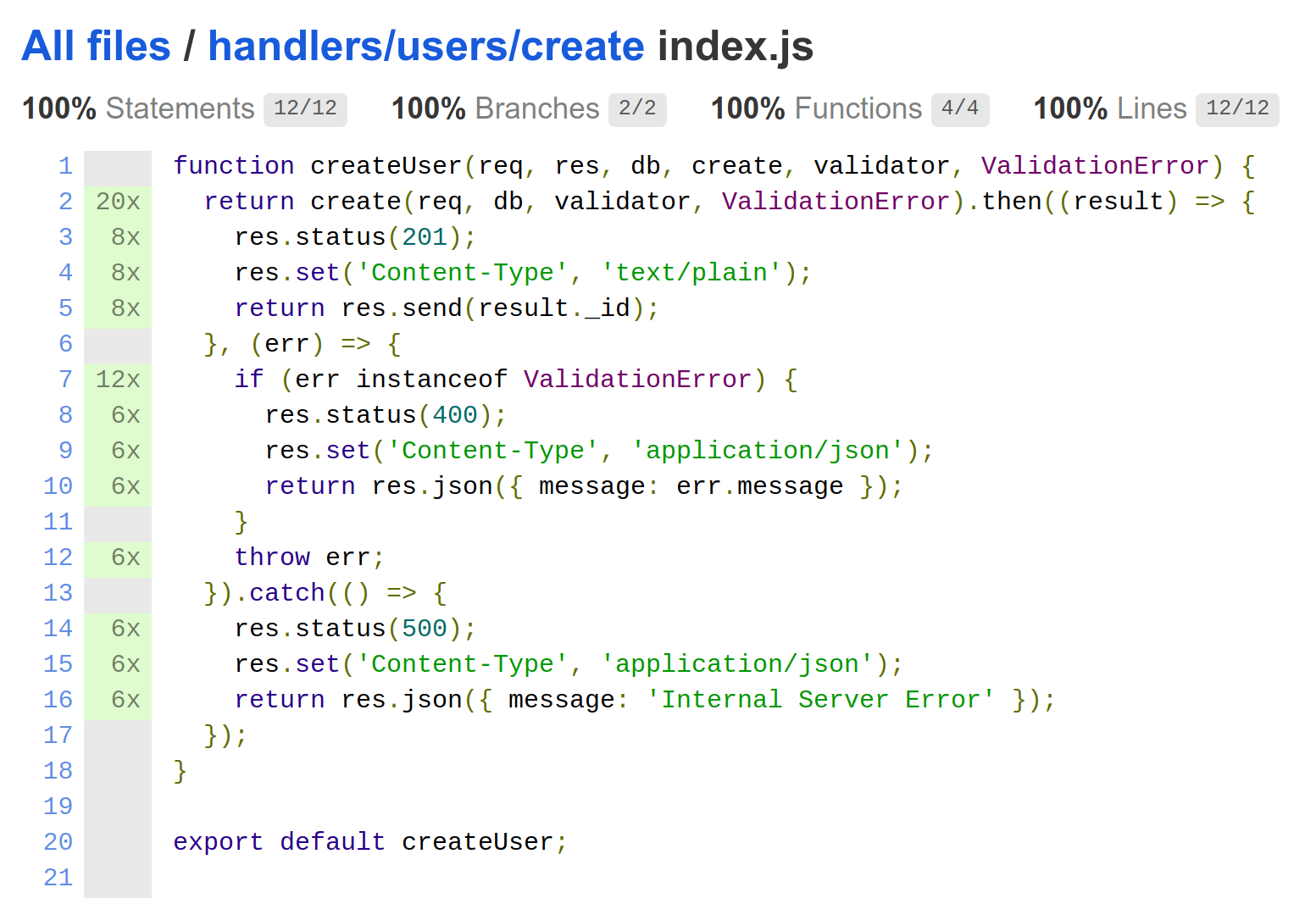

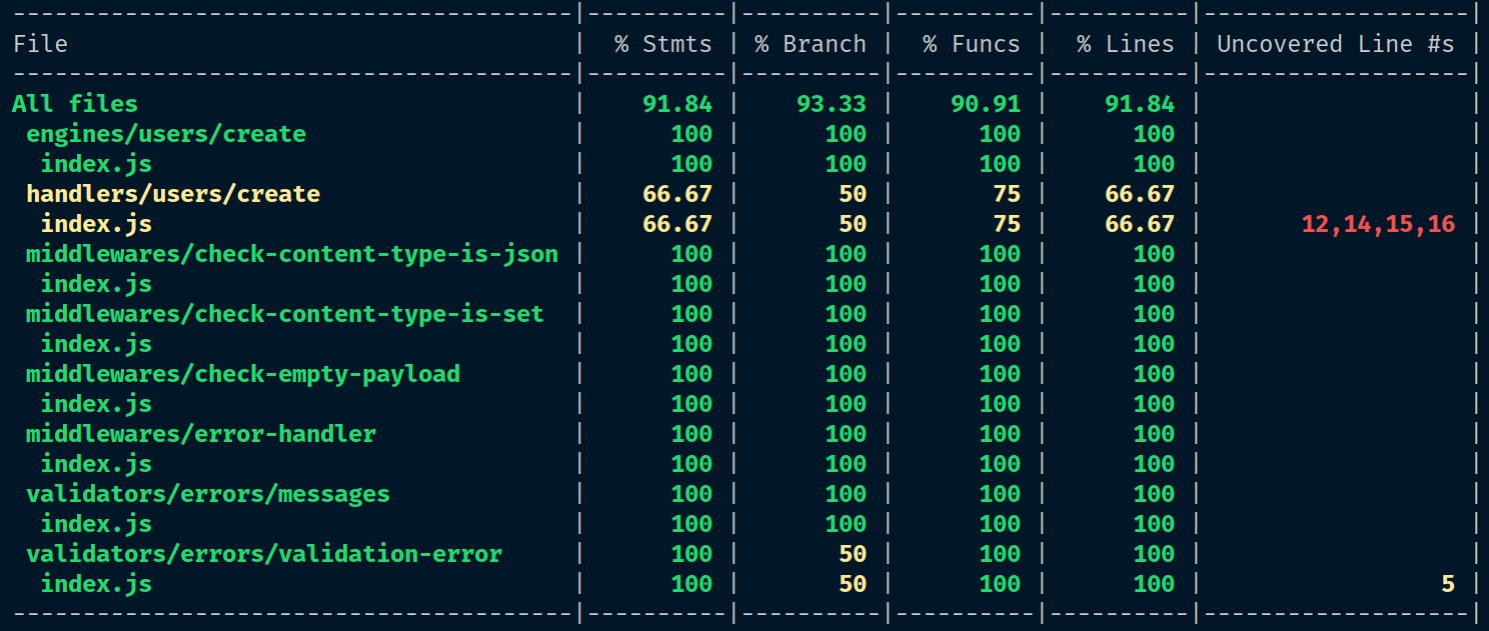

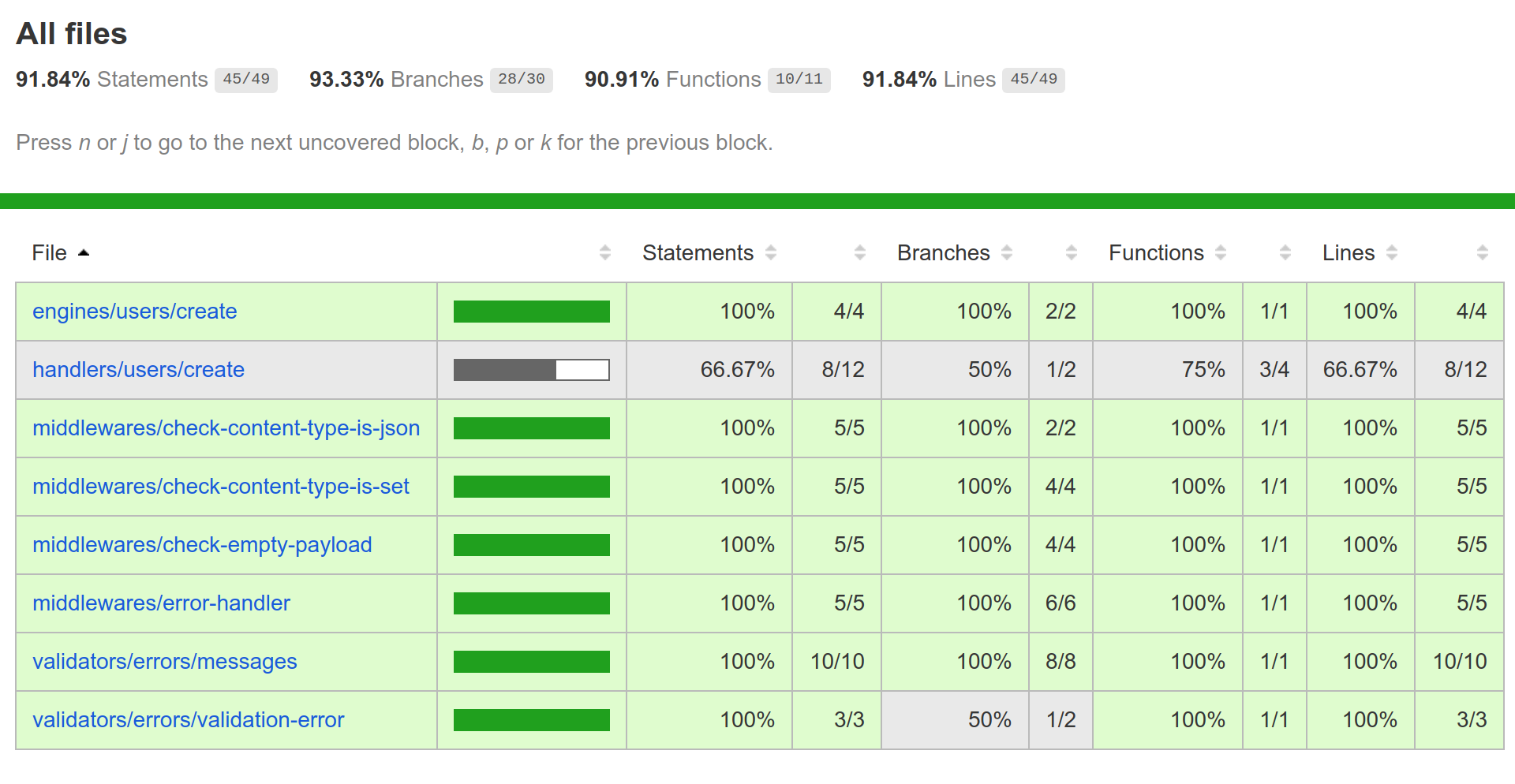

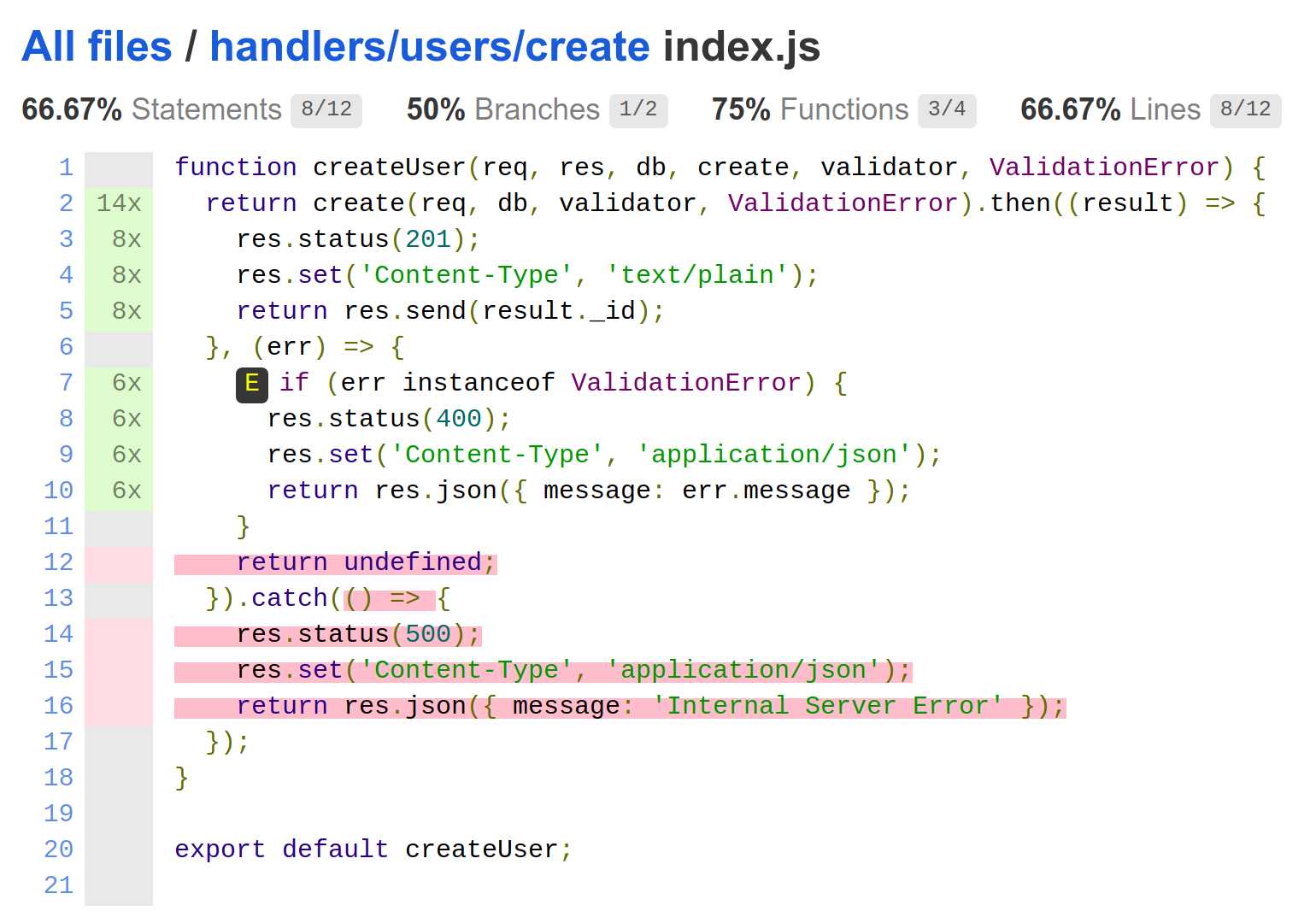

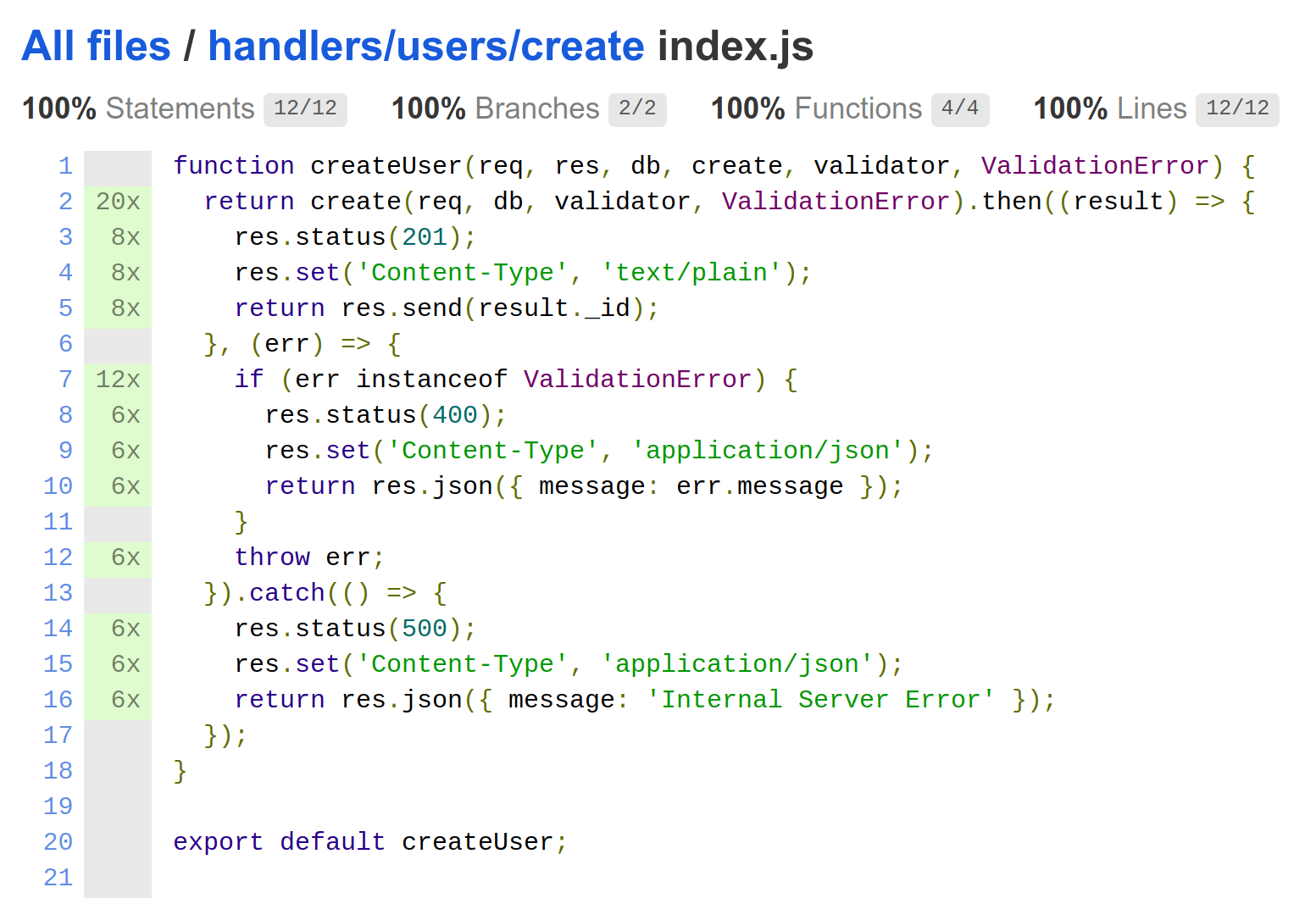

Chapter 8, Writing Unit/Integration Tests, will teach you how to use Mocha to write unit and integration tests. In order to isolate our unit tests from external dependencies, we will refactor our code to follow a Dependency Injection (DI) pattern, and use Sinon's spies and stubs to mock those dependencies. Lastly, we will use Istanbul/nyc to provide test coverage reports, which will help us identify errors and improve the quality of our code.

Chapter 9, Designing Our API, begins with a discussion of representational state transfer (REST)—what it is, and what it is not. Then, we will examine different types of consistency – Common, Local, Transversal, Domain, and Perennial – and see how they contribute to providing an intuitive developer experience.

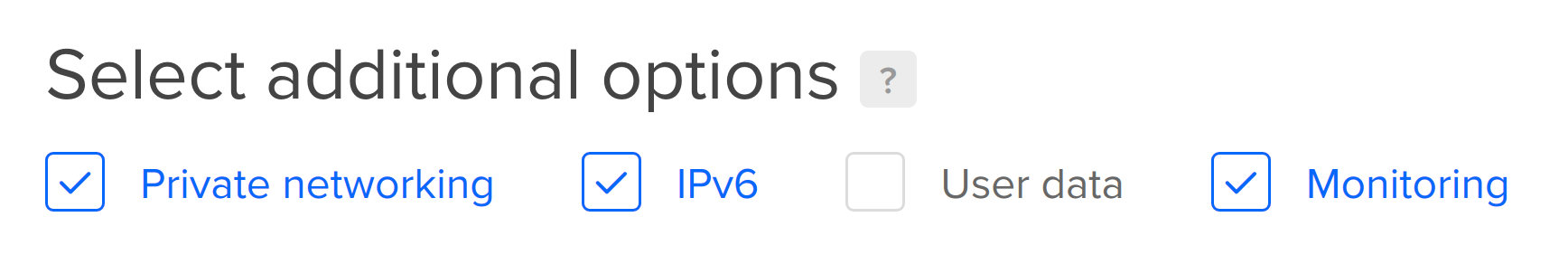

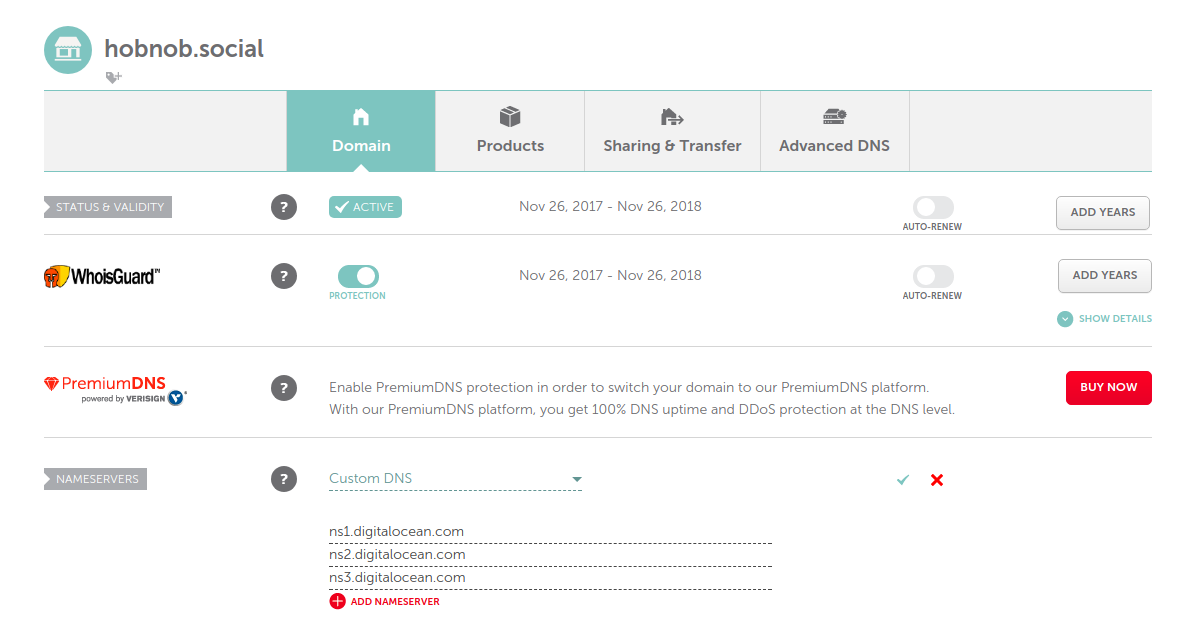

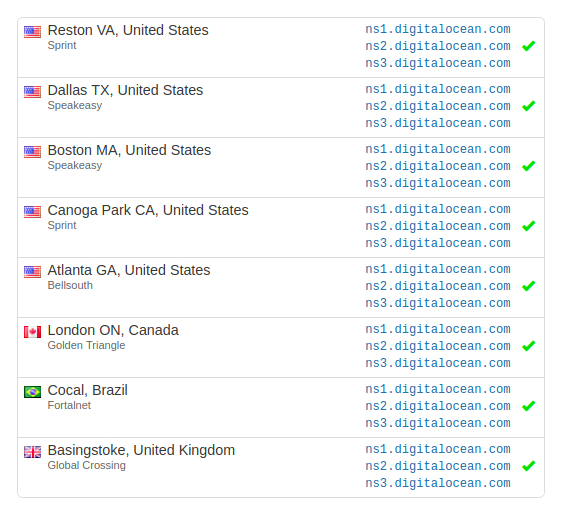

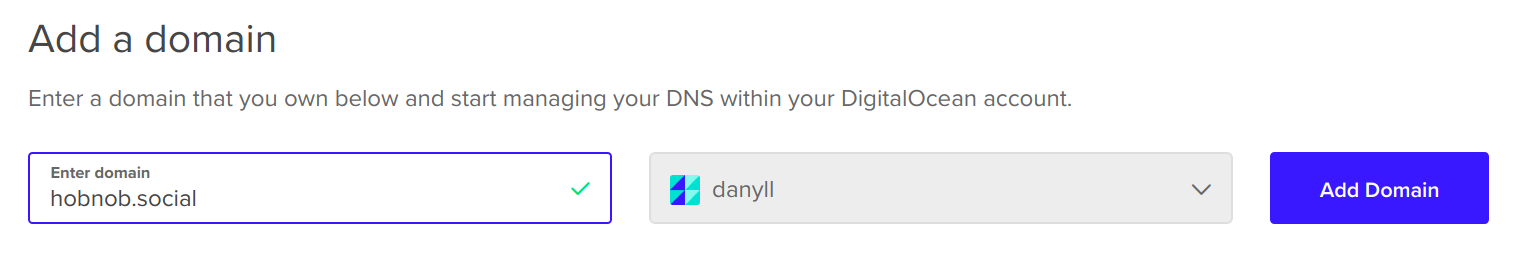

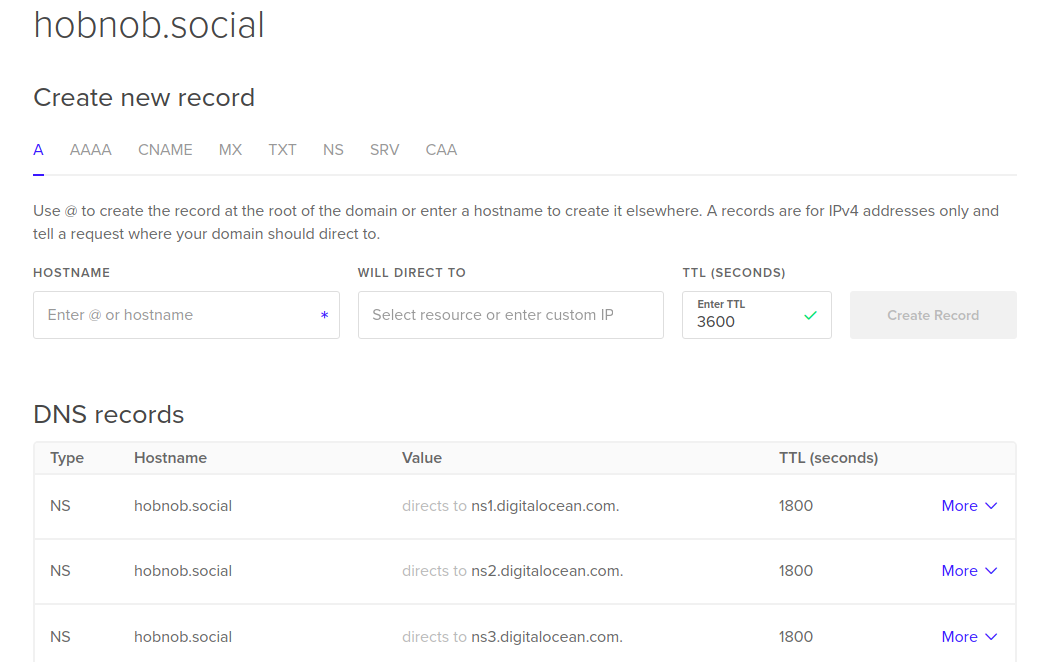

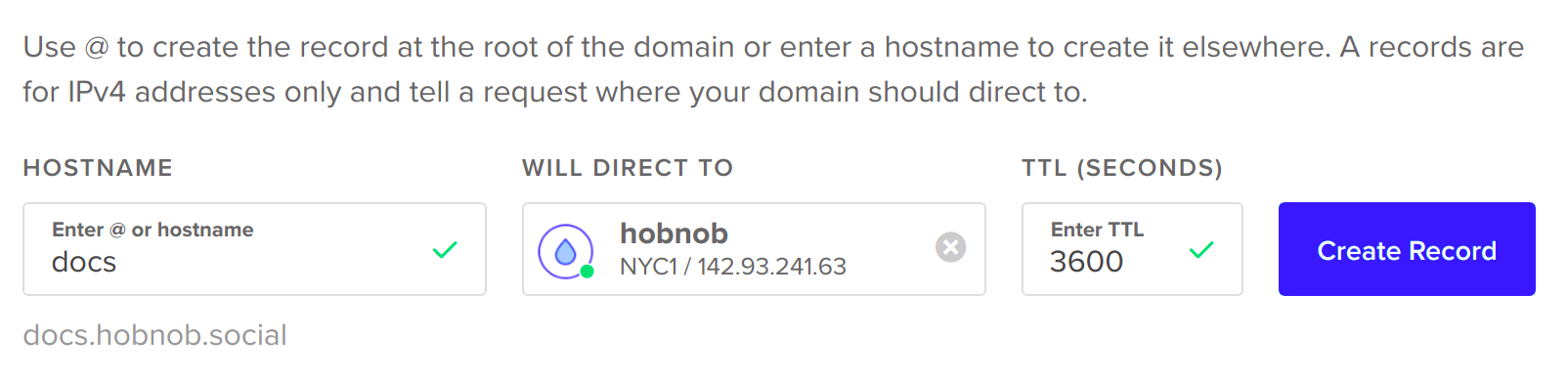

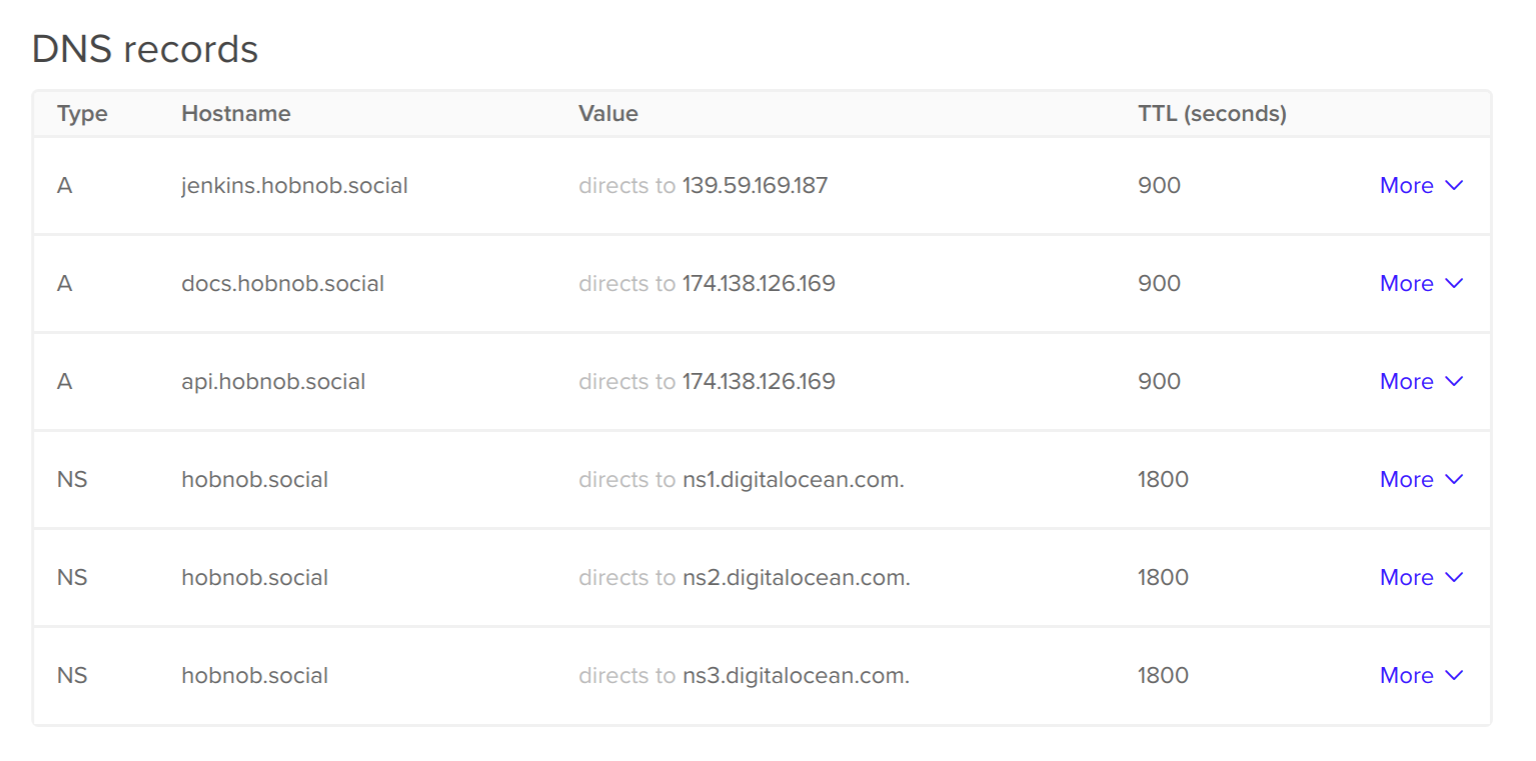

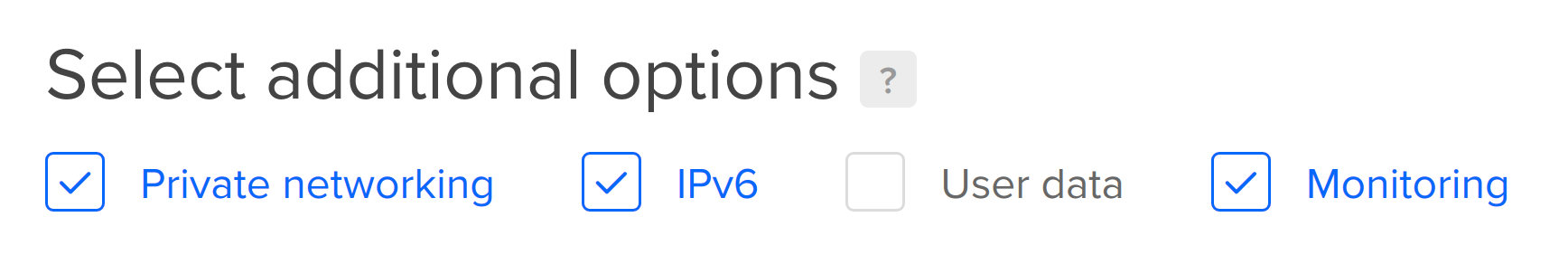

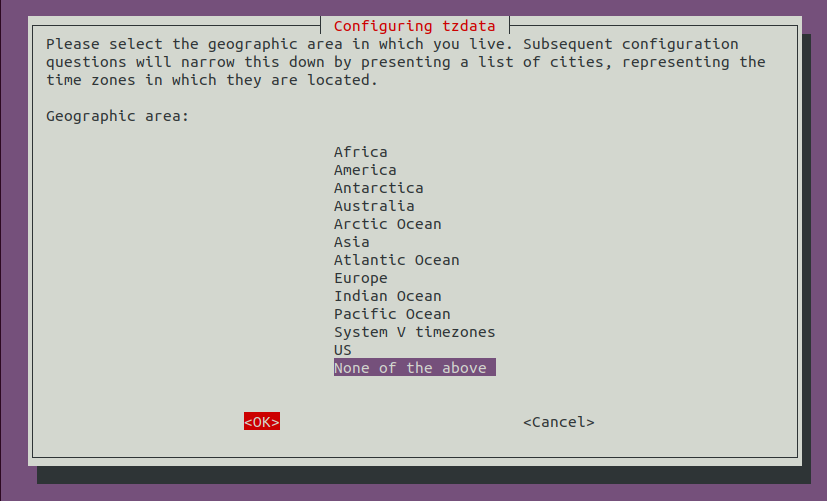

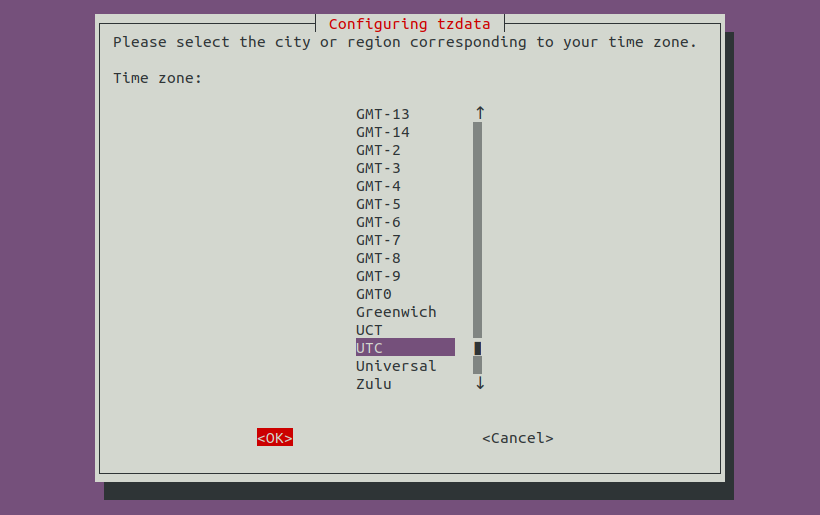

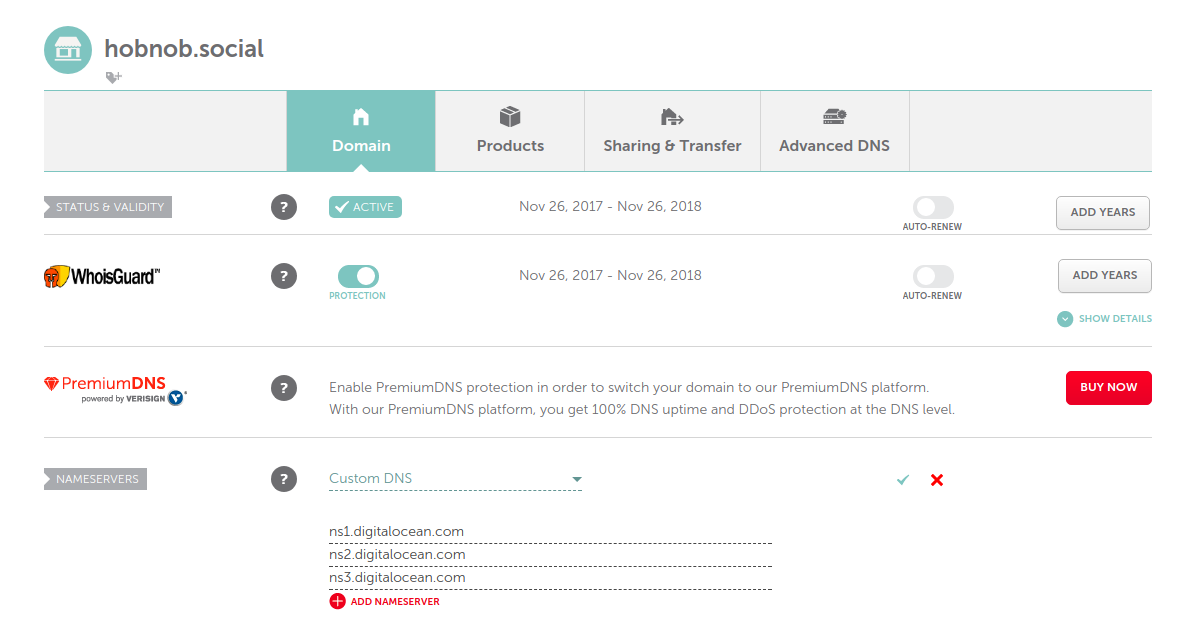

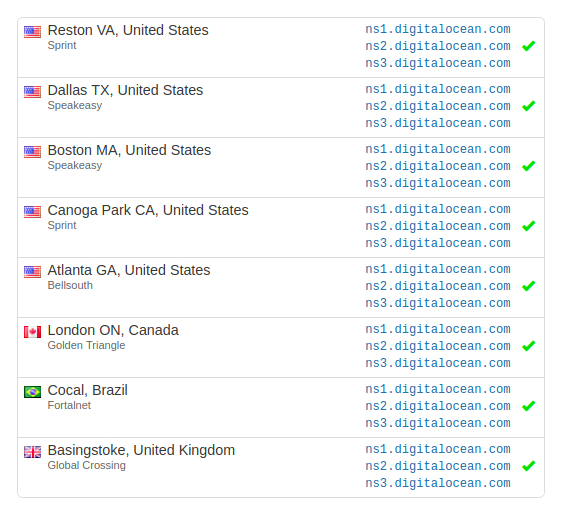

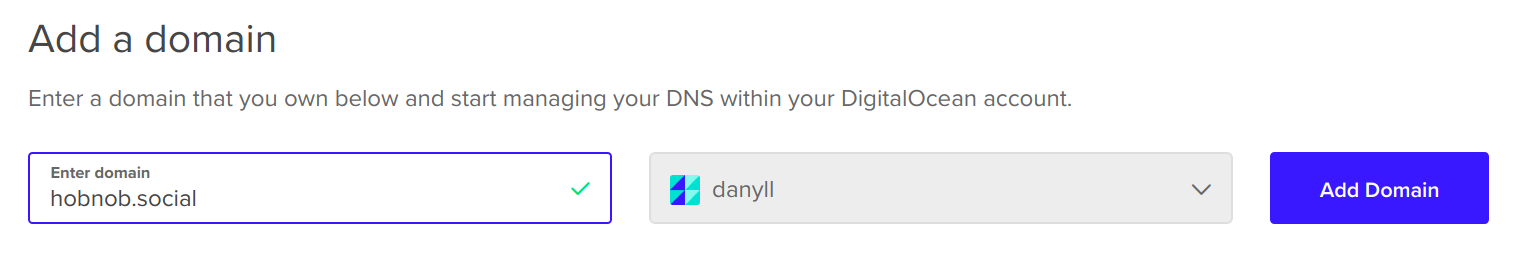

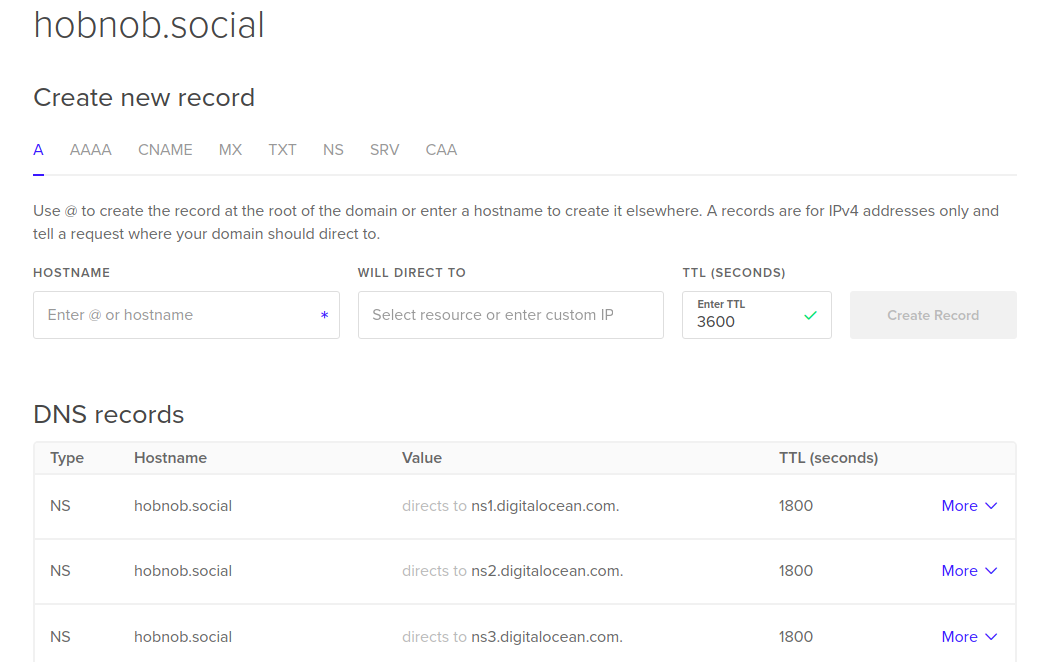

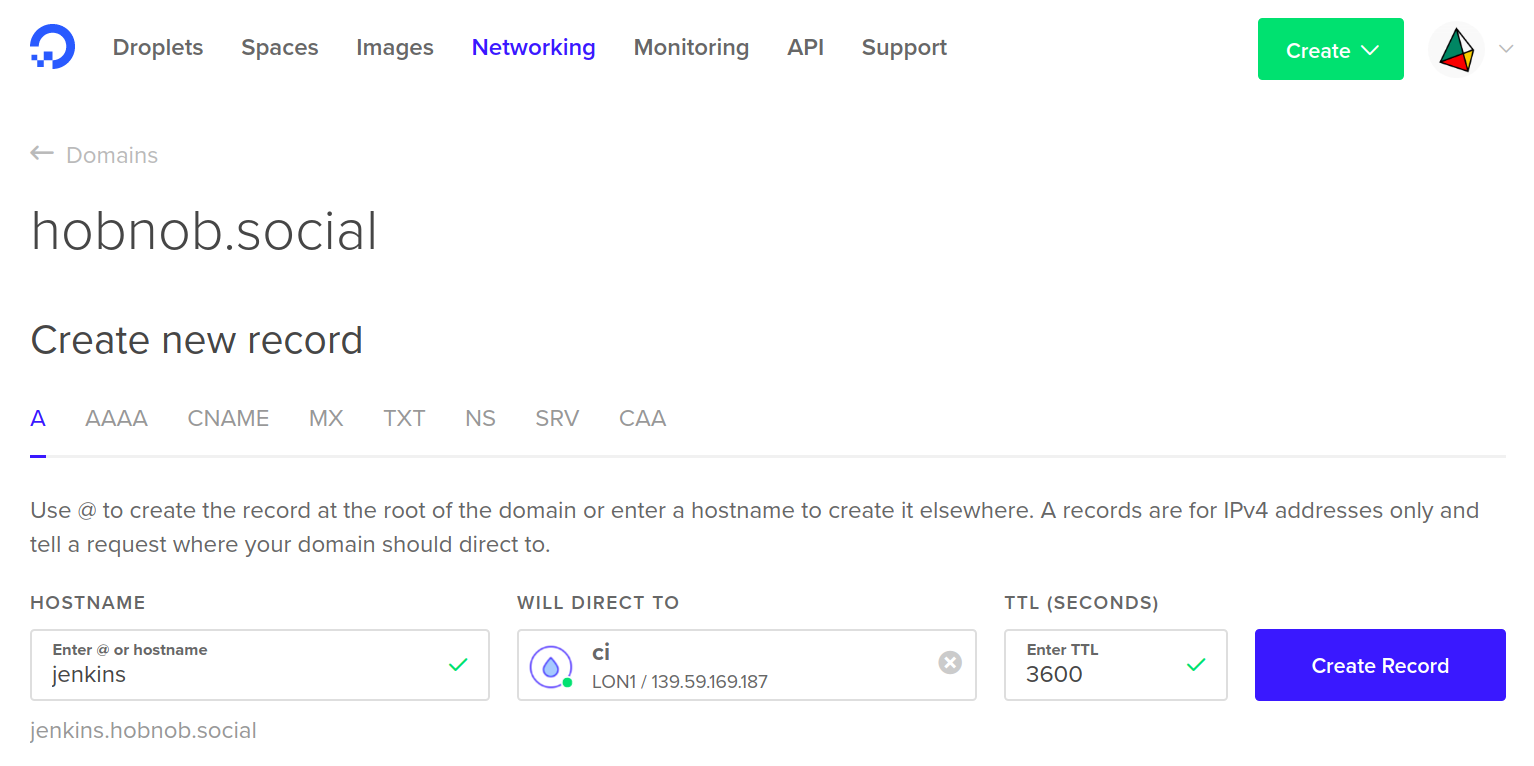

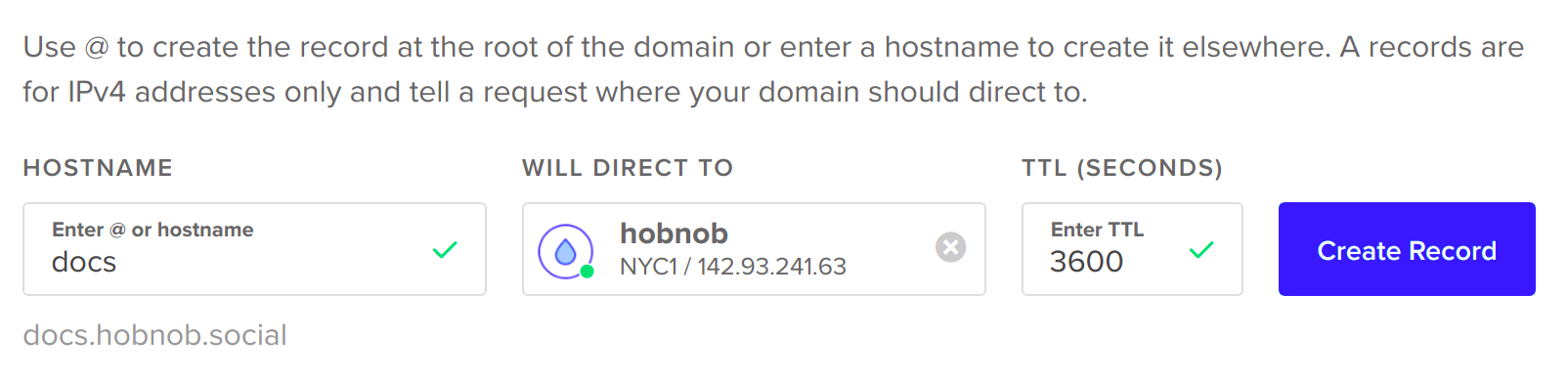

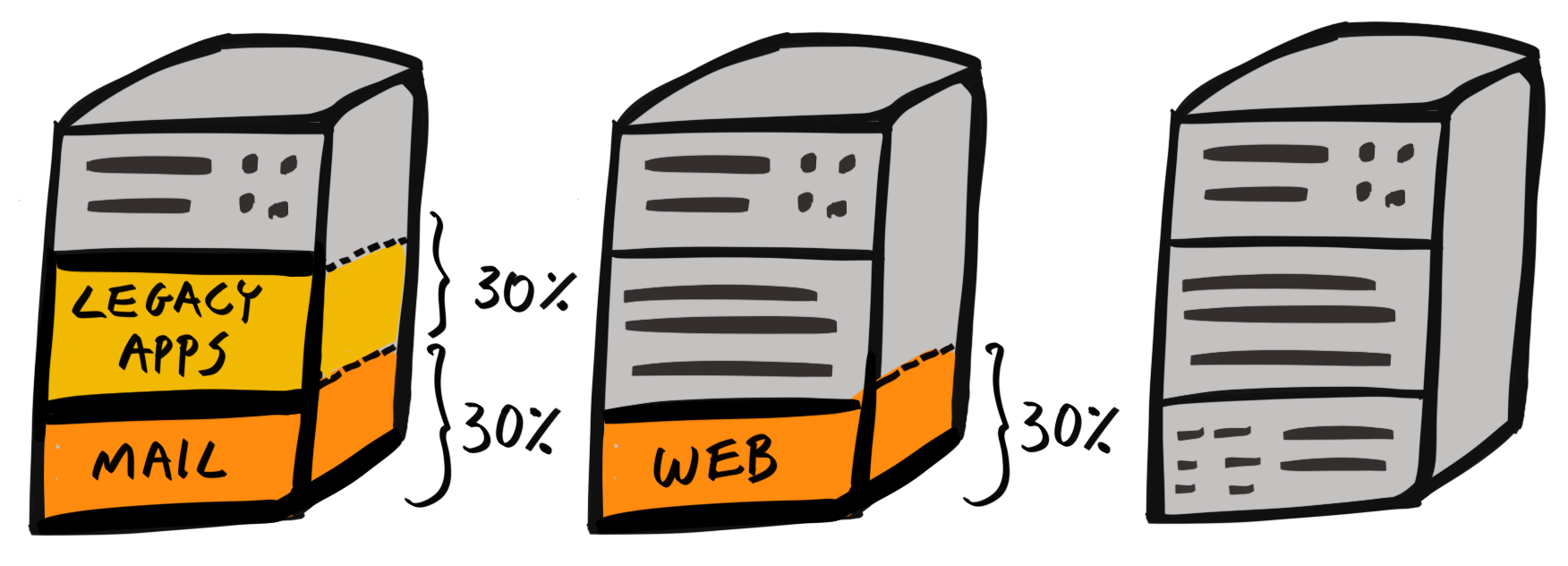

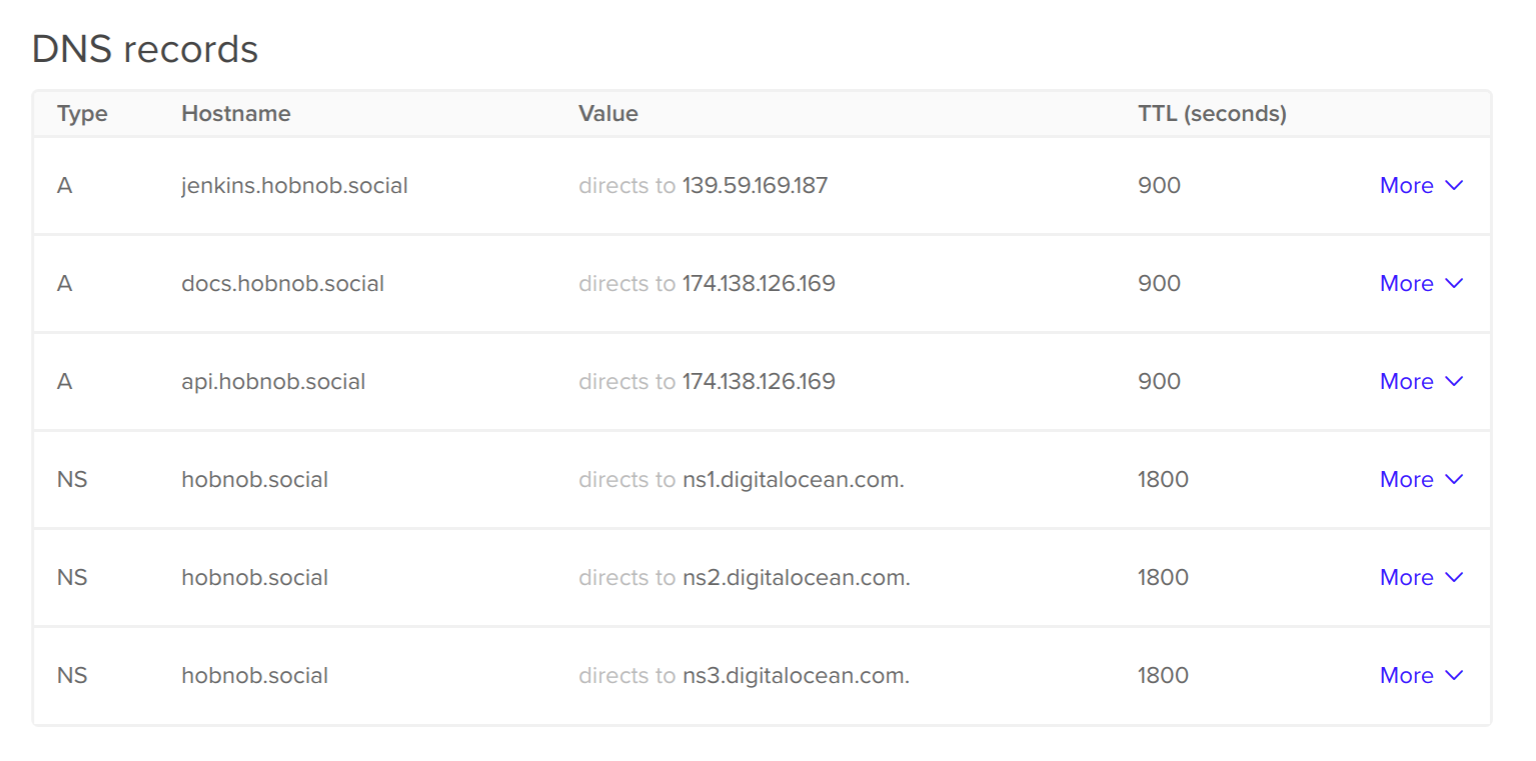

Chapter 10, Deploying Your Application on a VPS, provides step-by-step instructions on how to deploy our API on a Virtual Private Server (VPS). You'll learn how to buy a domain, configure Domain Name System (DNS) records, set up NGINX as a reverse proxy, and keep your Node.js process alive with PM2.

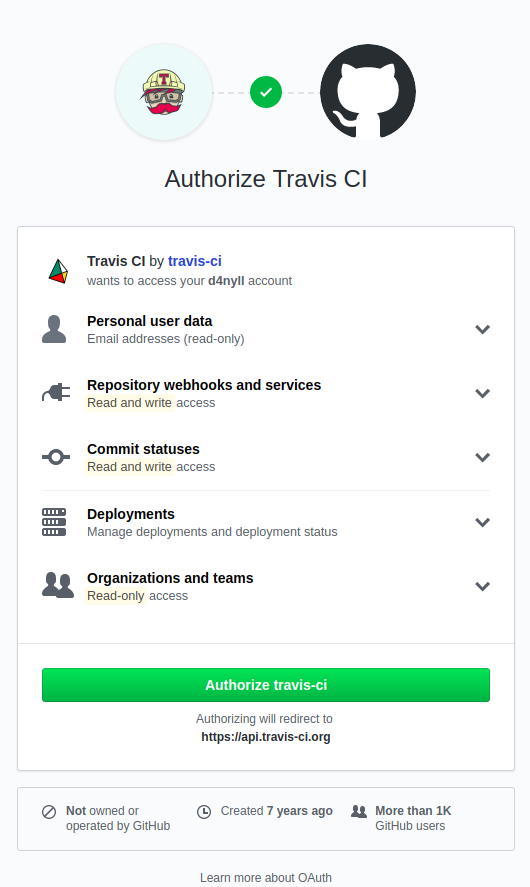

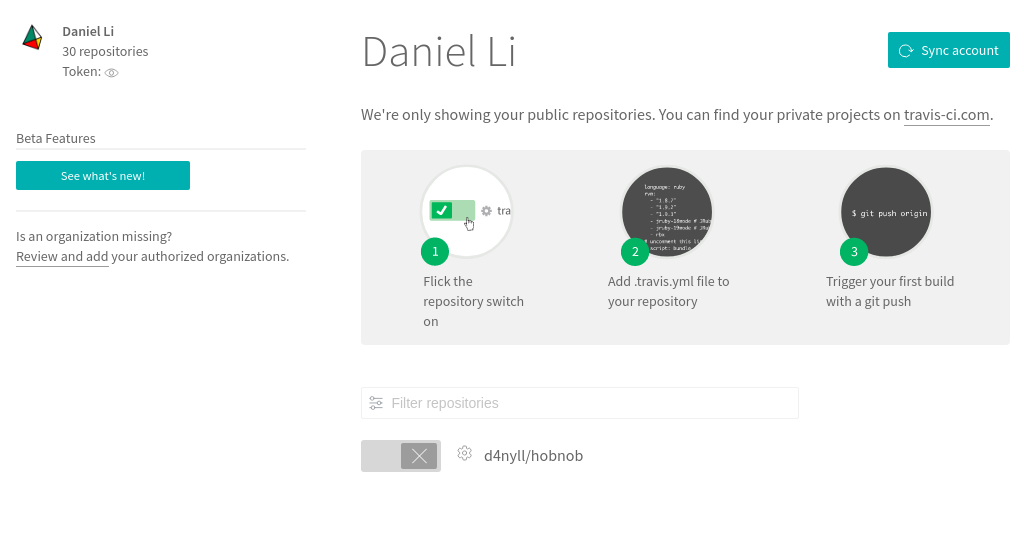

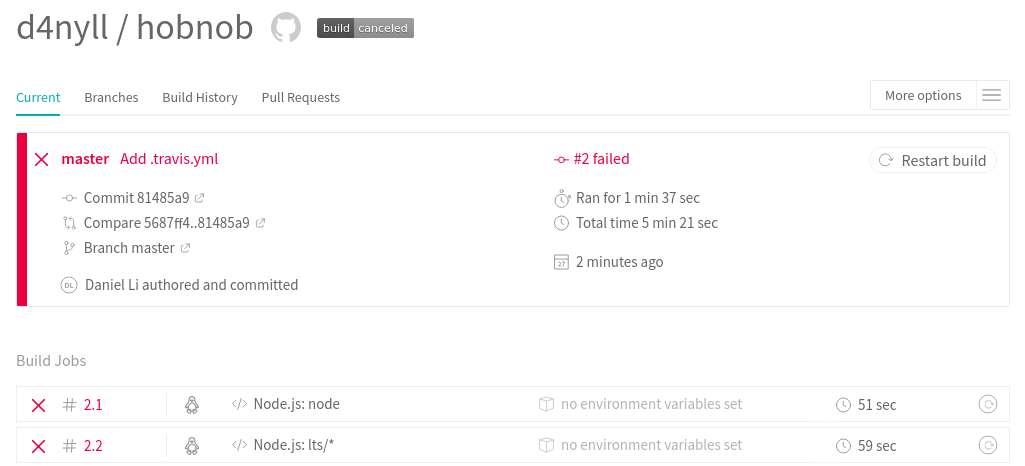

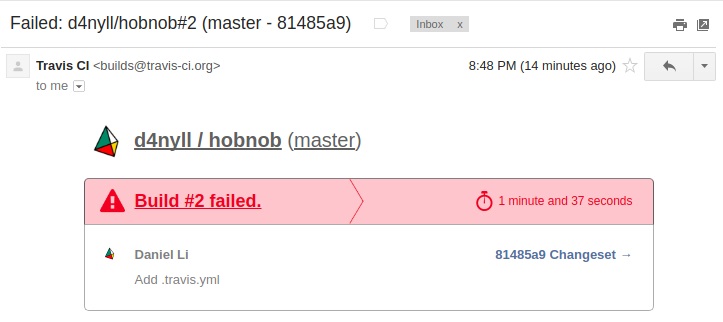

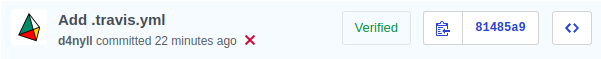

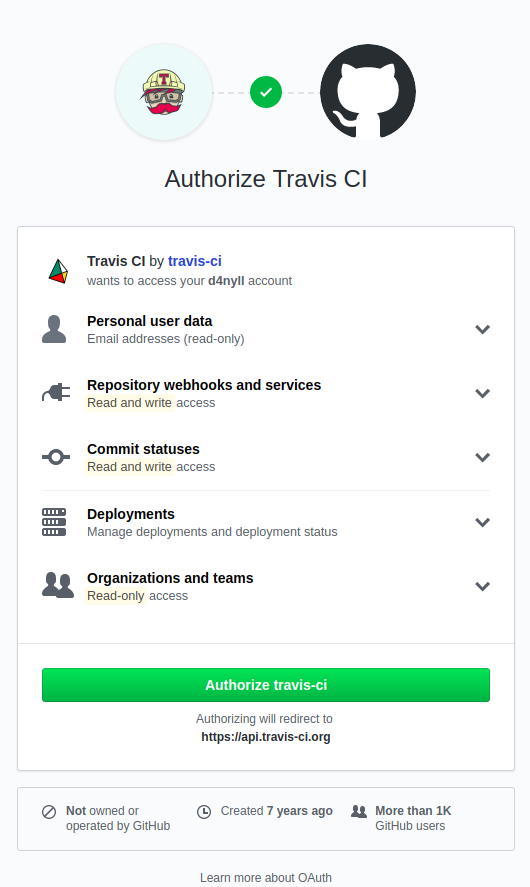

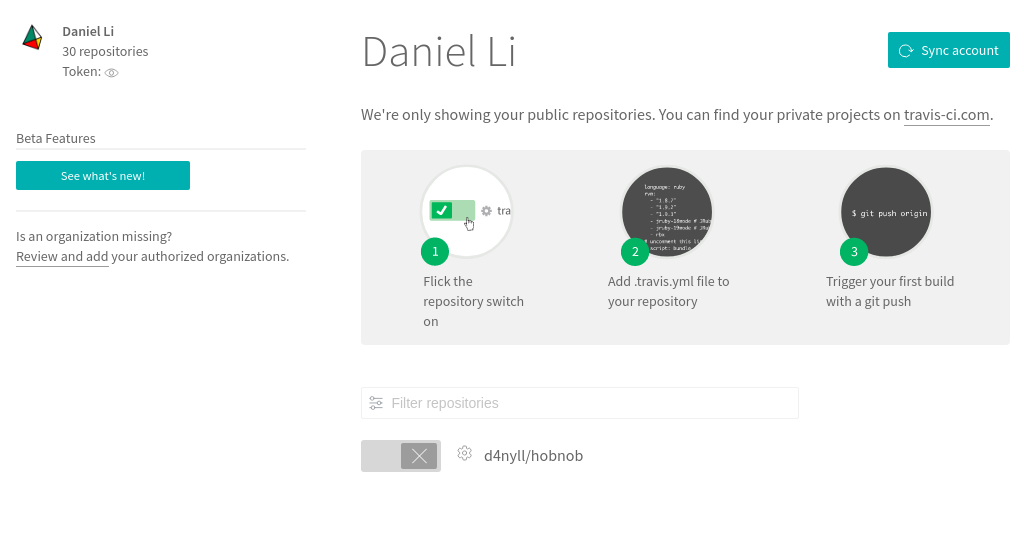

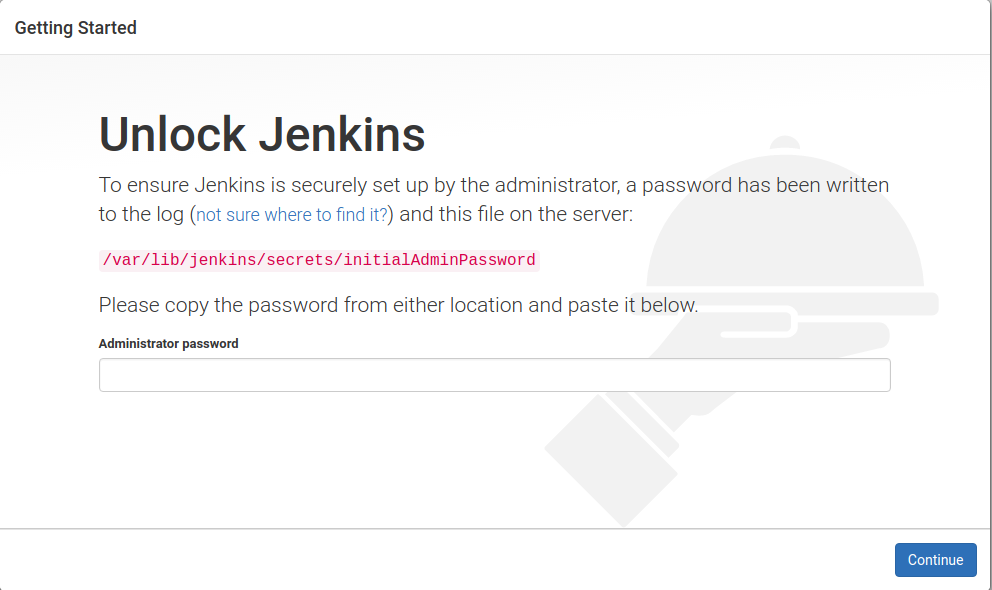

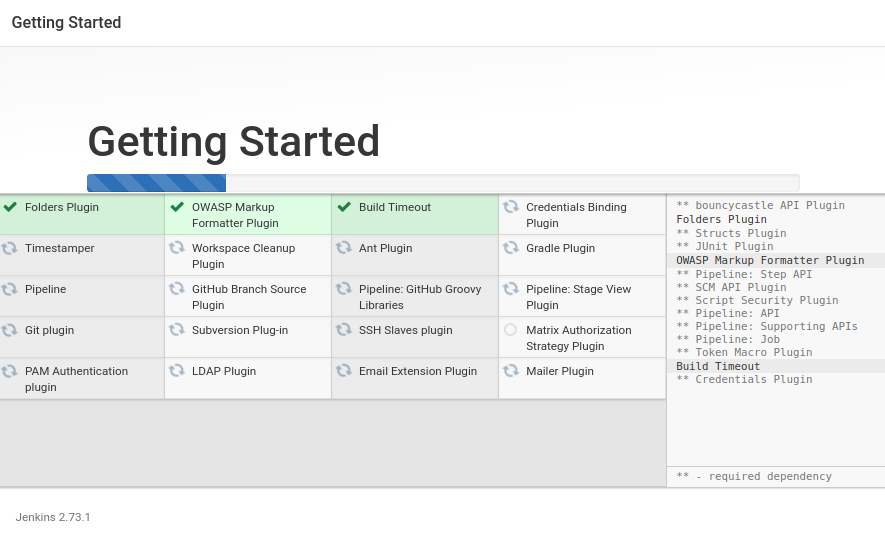

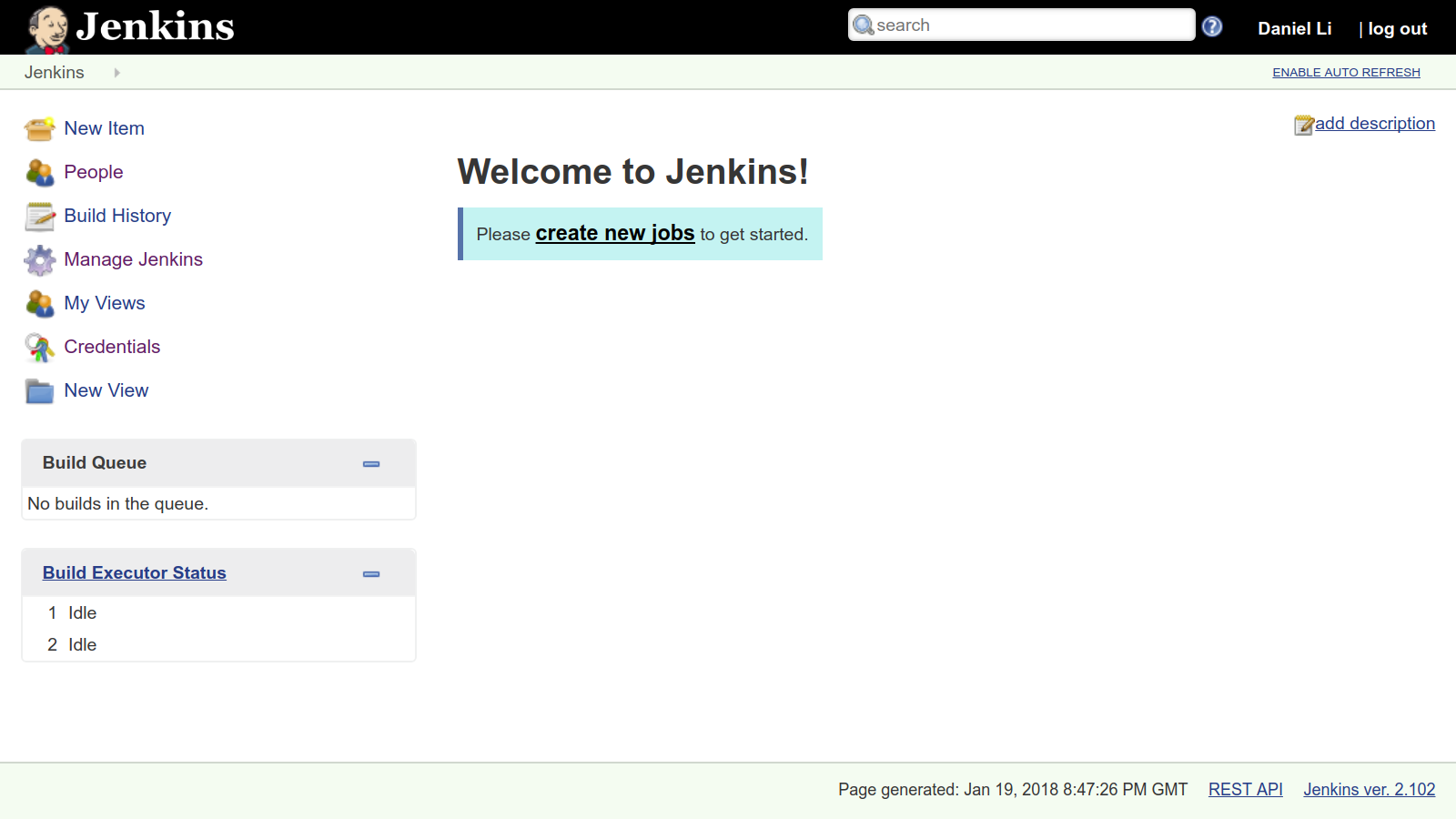

Chapter 11, Continuous Integration, implements a Continuous Integration (CI) pipeline into our development process. We begin by using a hosted platform called Travis, before deploying our own self-hosted Jenkins CI server.

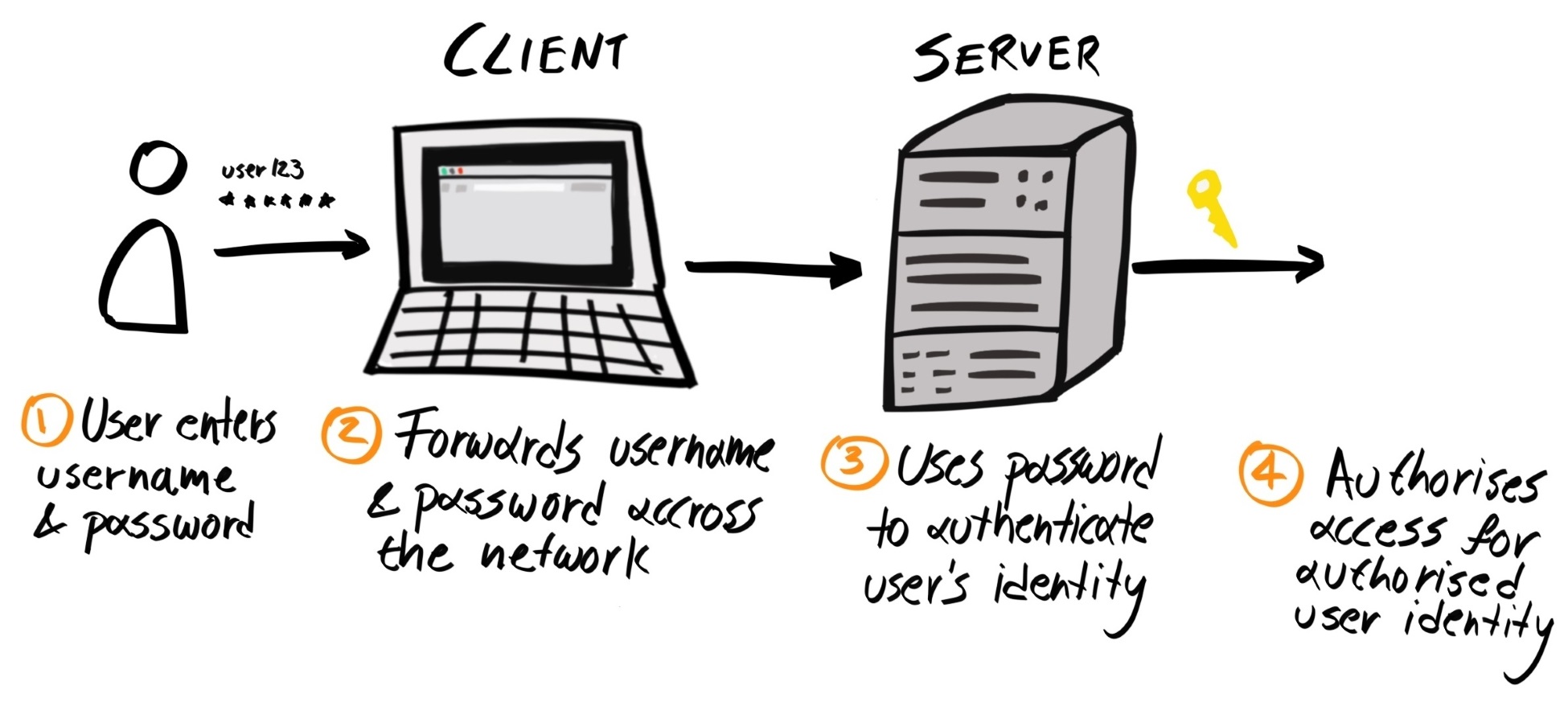

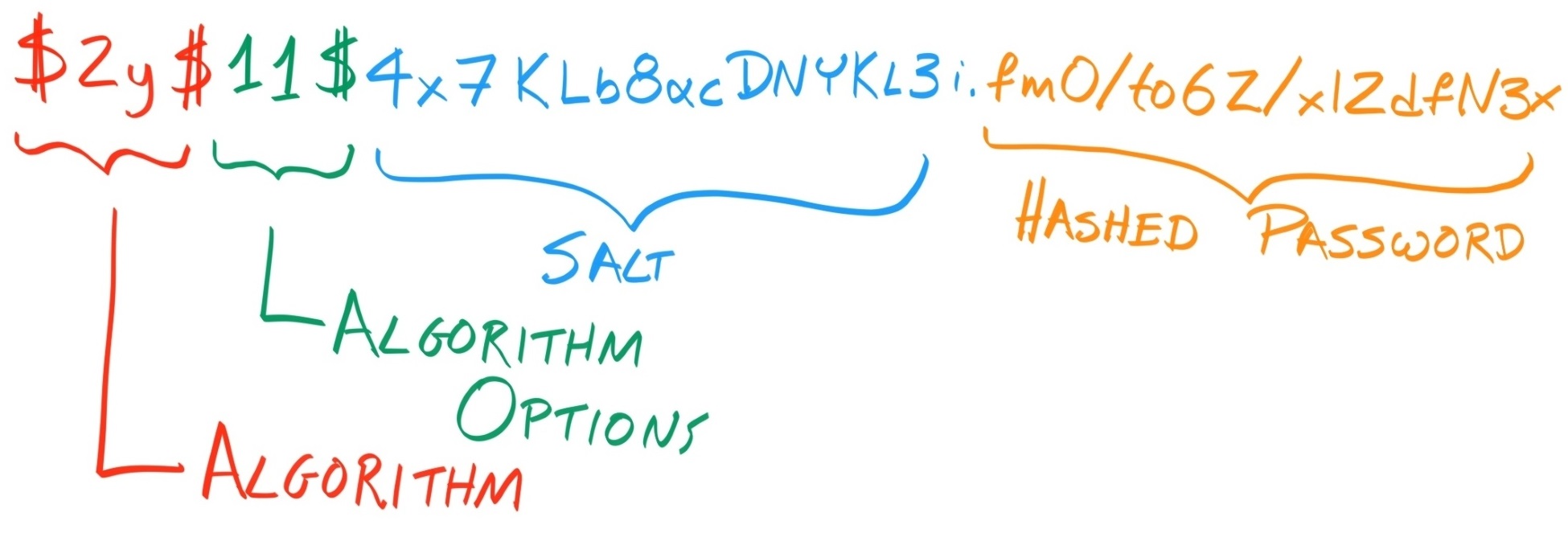

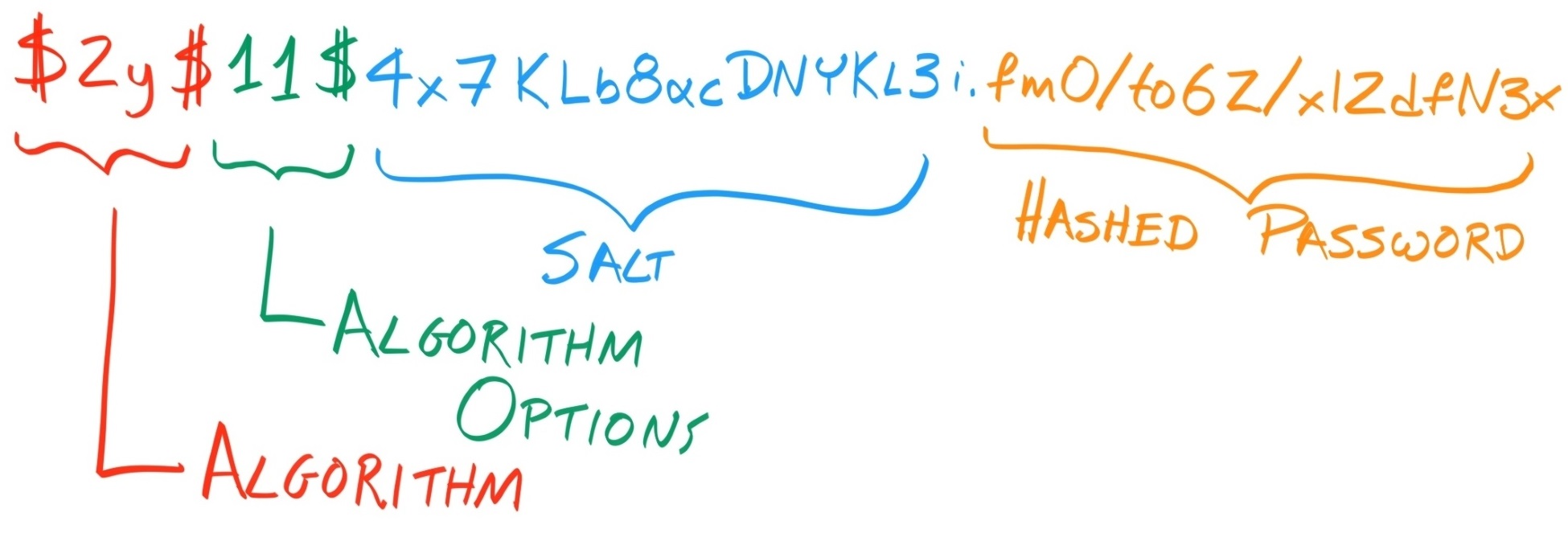

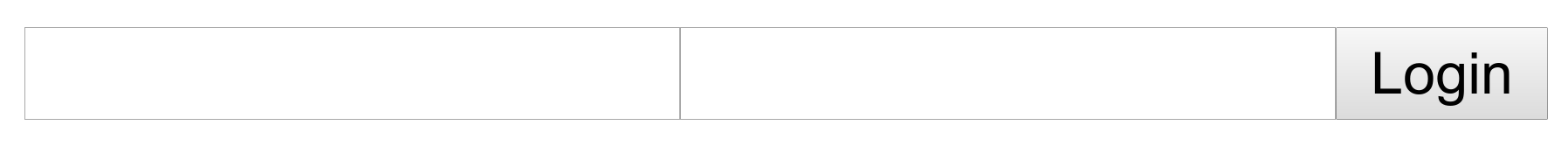

Chapter 12, Security: Authentication and Authorization, introduces you to concepts underpinning authorization and password-, session-, and token-based authentication. These include cryptographic hashing, salts, and JSON Web Tokens (JWTs).

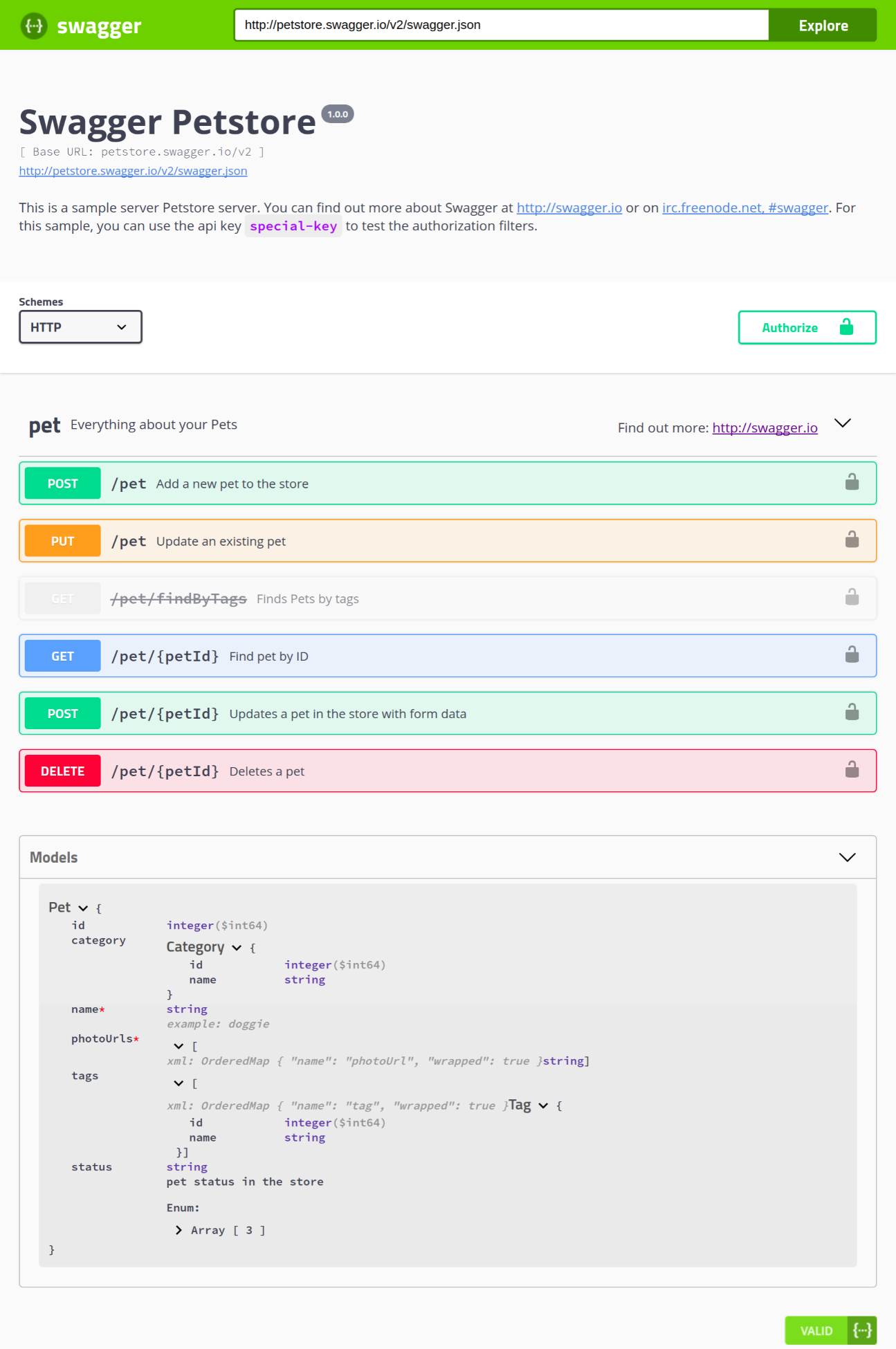

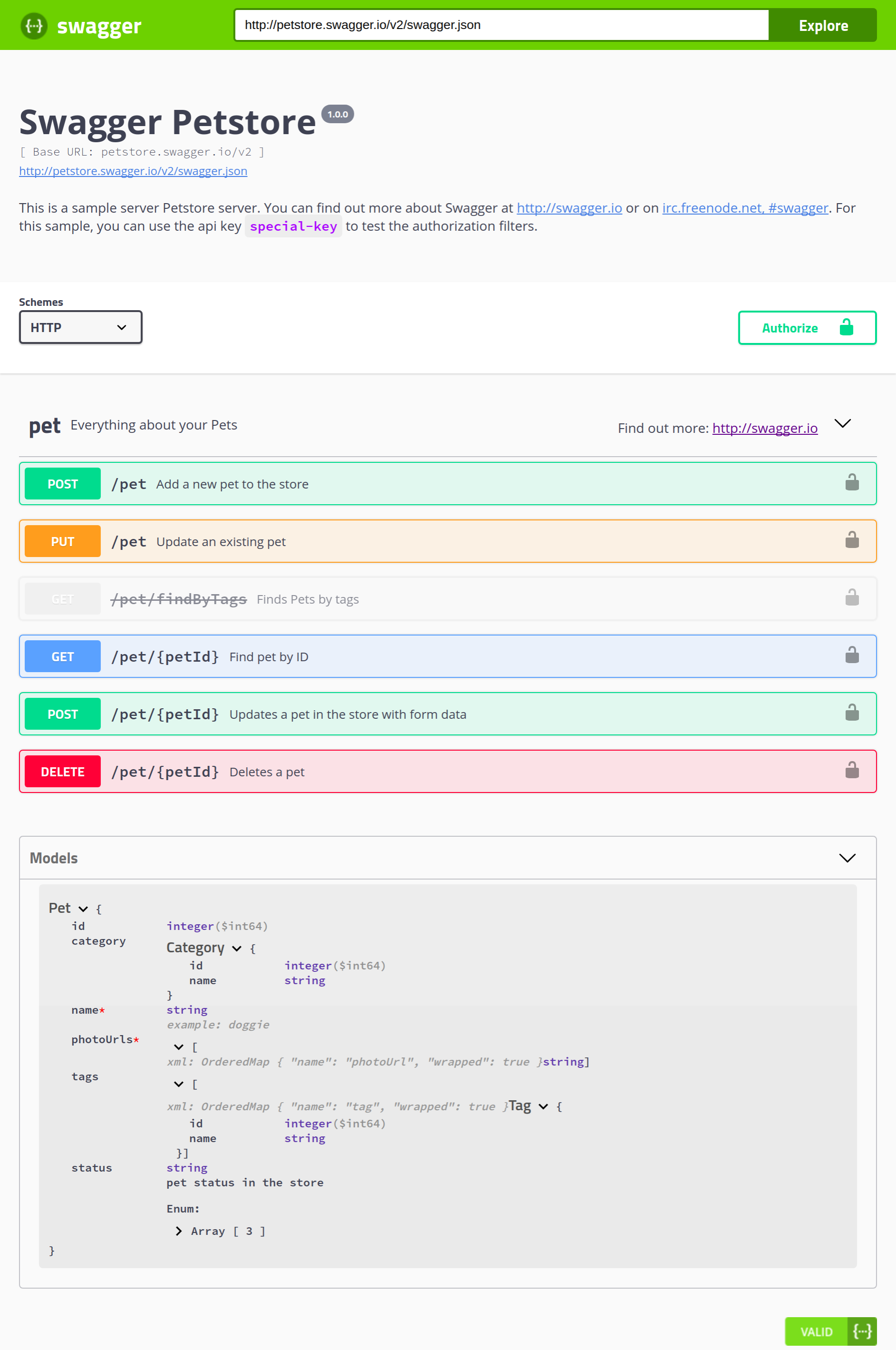

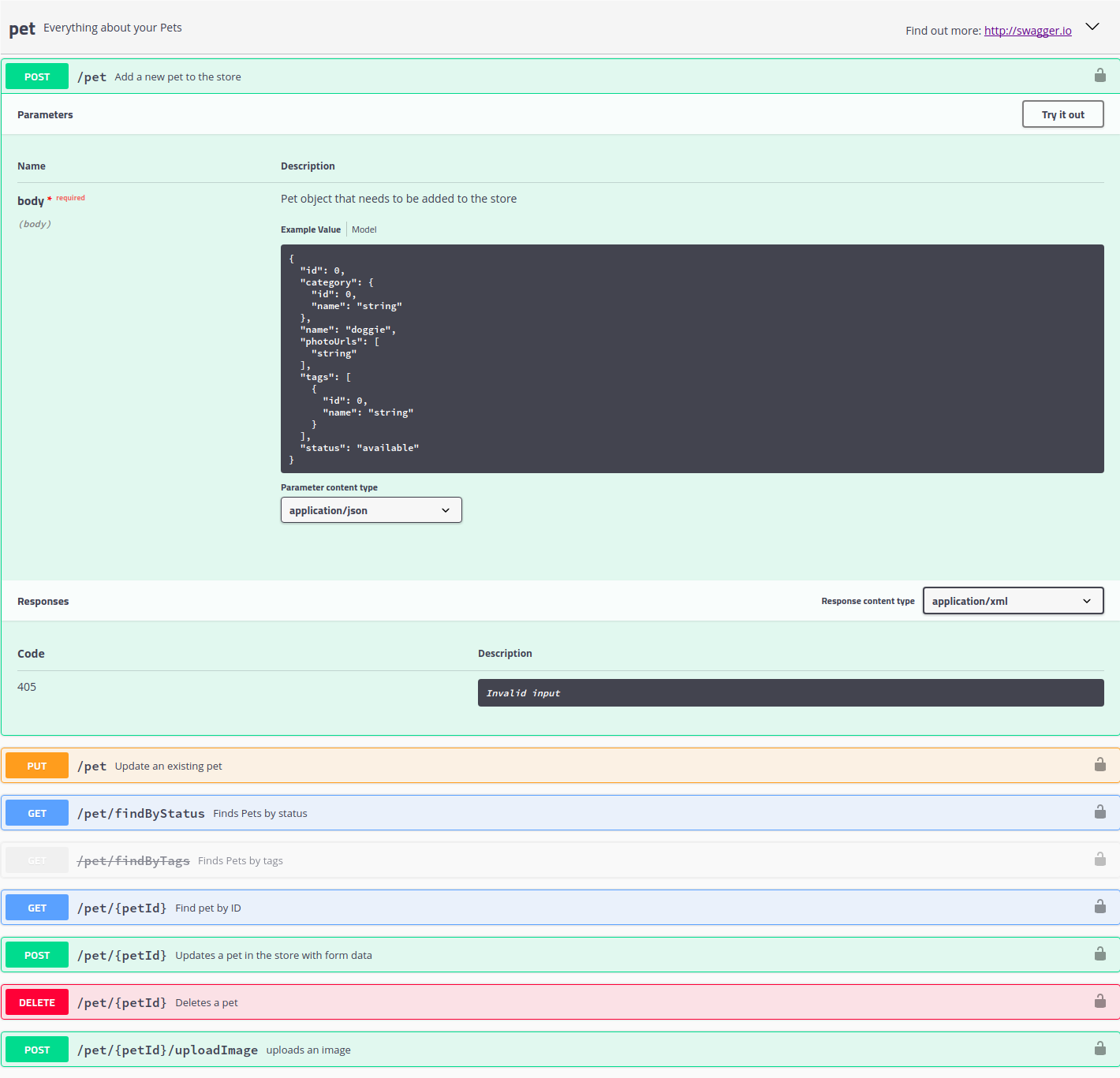

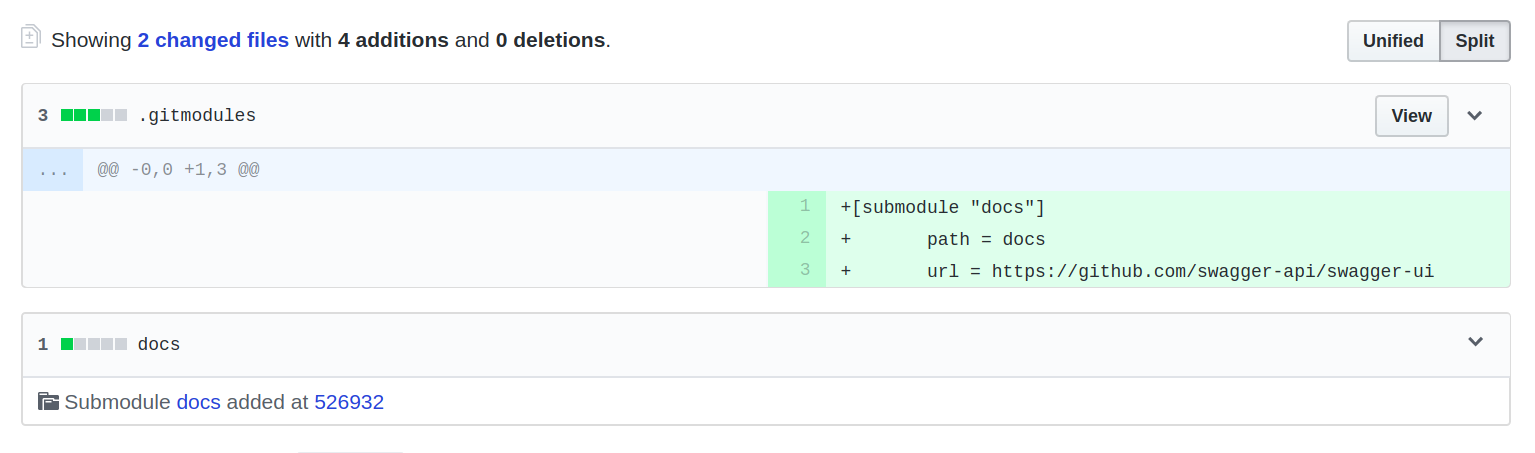

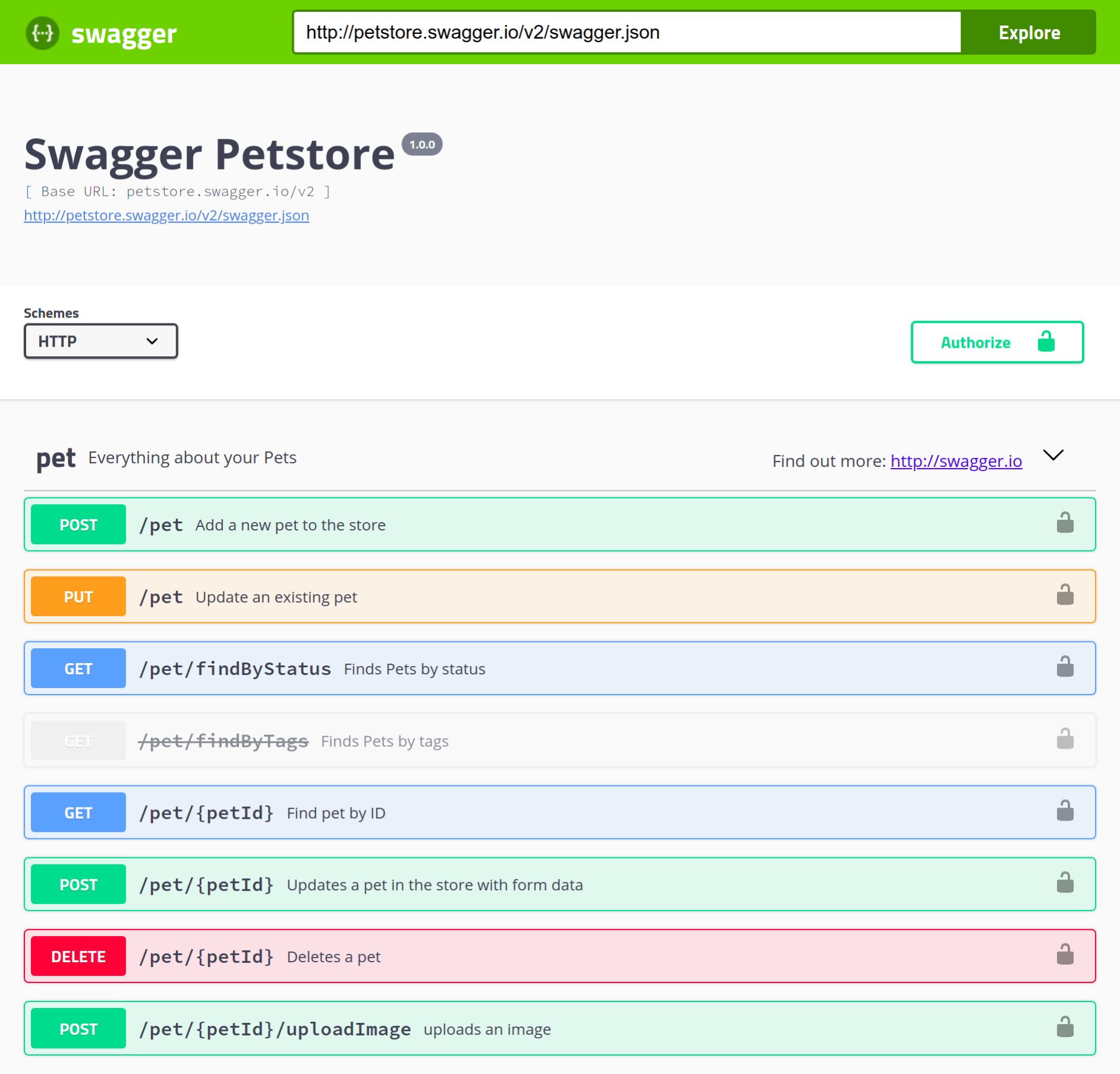

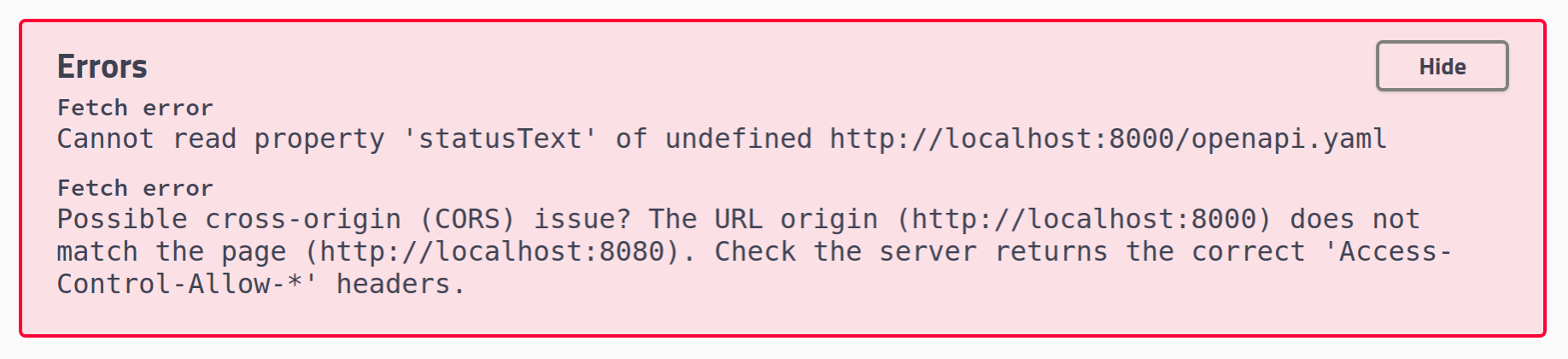

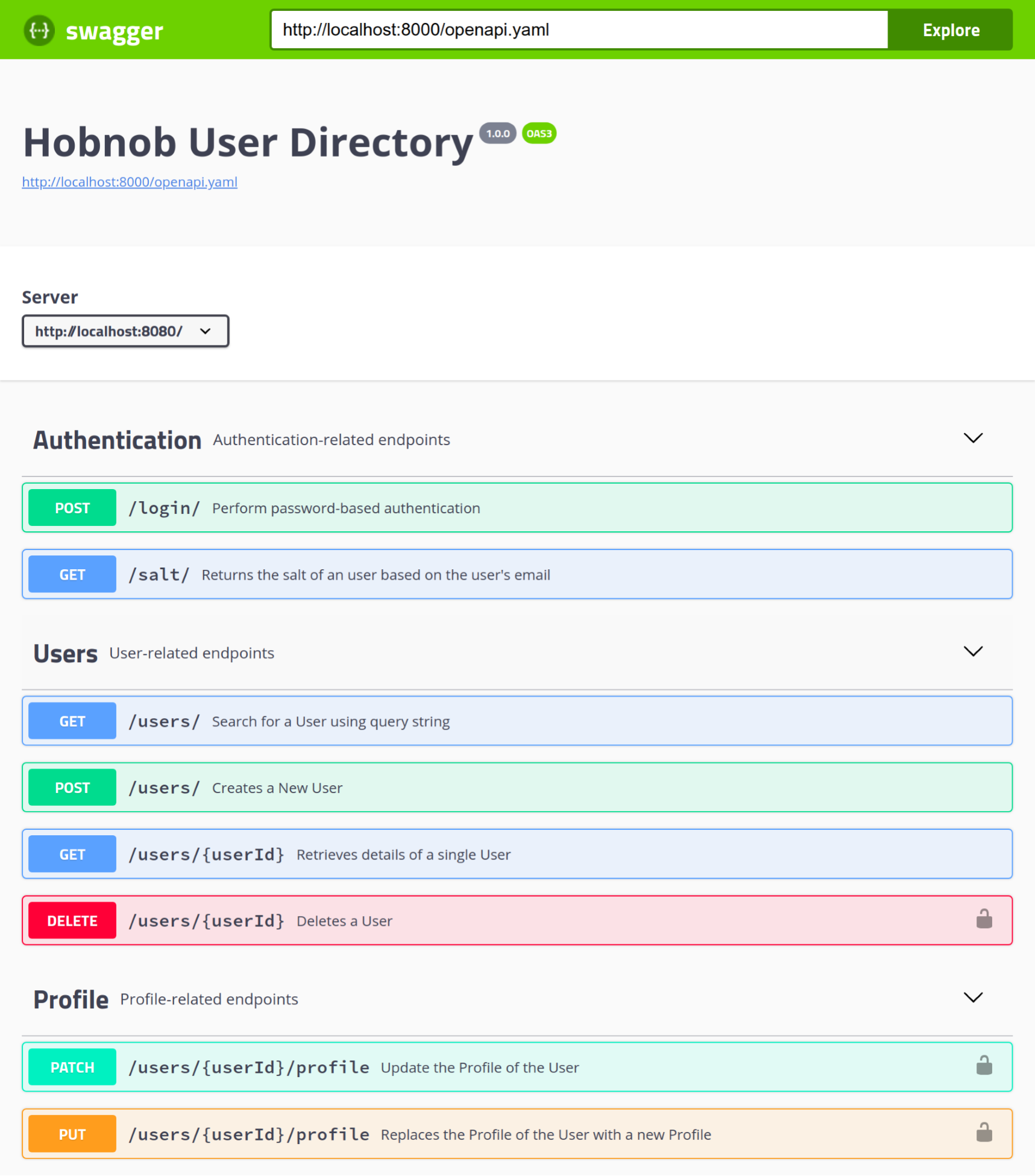

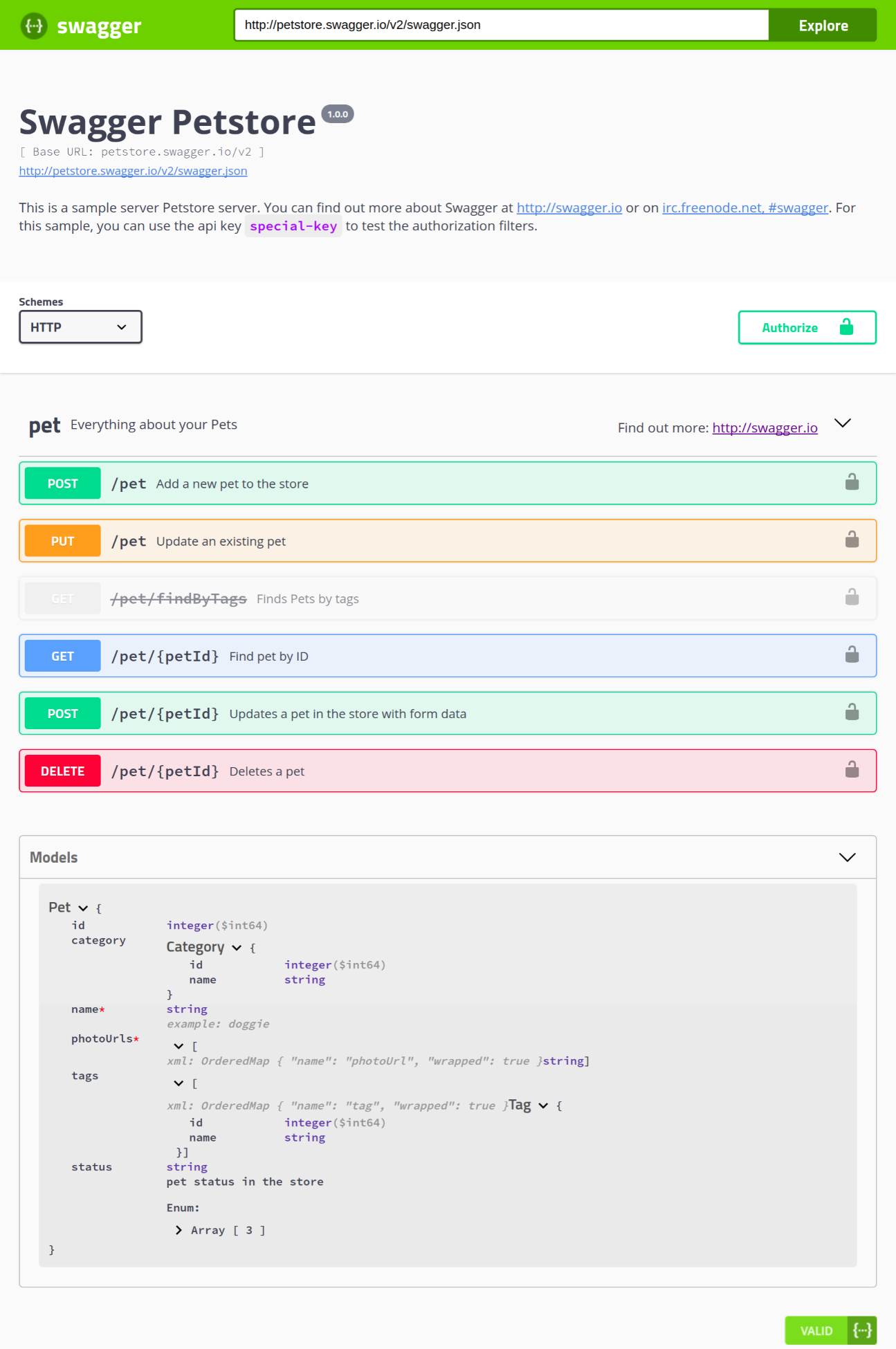

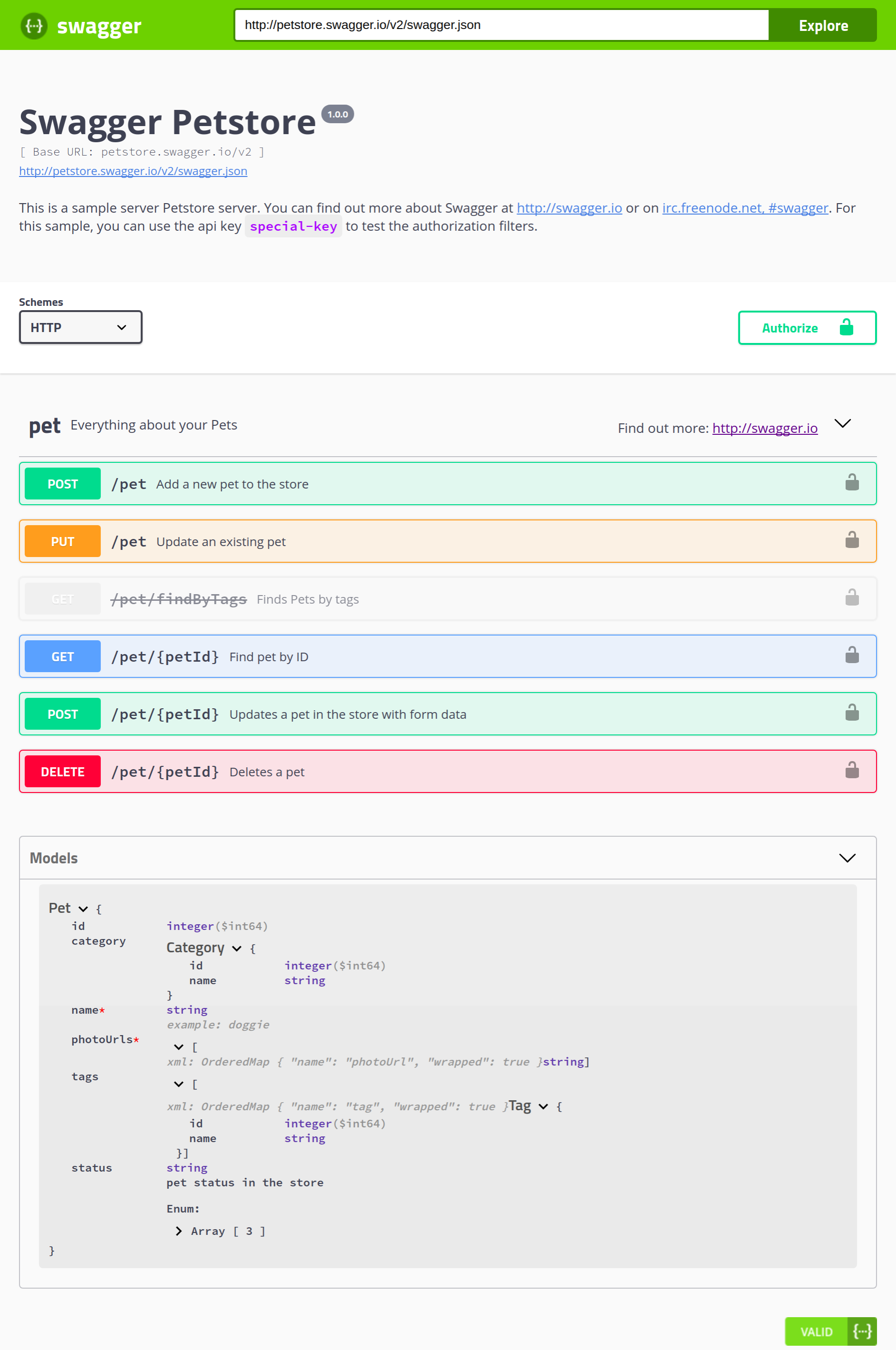

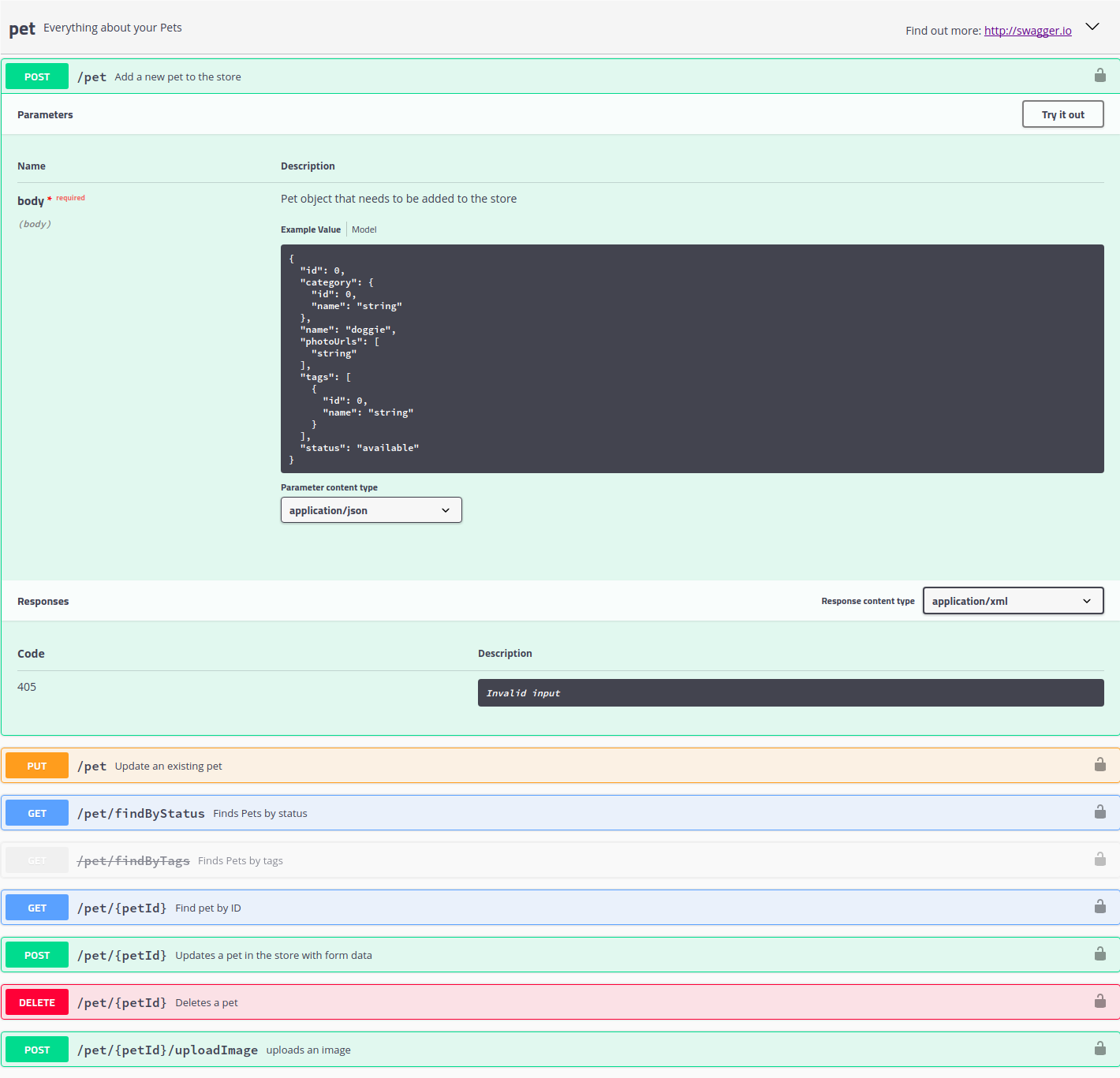

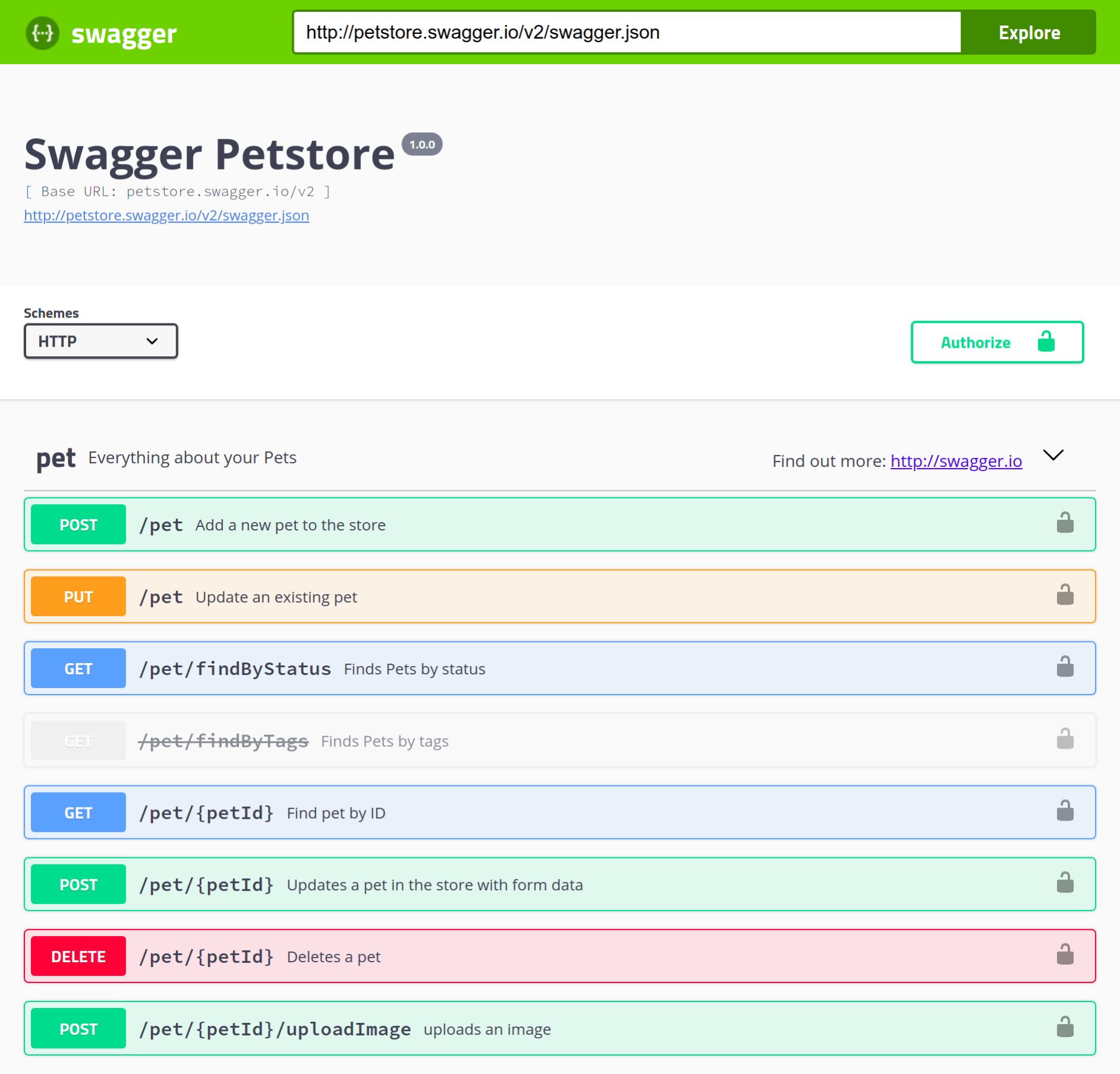

Chapter 13, Documenting Our API, completes the development of our API by documenting it using Swagger. You will learn how to write OpenAPI-compliant specifications in YAML, and visualize them using Swagger UI.

Chapter 14, Creating UI with React, teaches you React from first principles, discussing concepts such as virtual DOM, pure components, and JSX. At the end of the chapter, we'll also compare different module bundlers and loaders, such as Webpack, Rollup, and SystemJS.

Chapter 15, E2E Testing in React, uses the React knowledge you've gained in the previous chapter to implement a TDD workflow involving Cucumber and Selenium and using headless browsers. We will follow this process as we implement client-side routing into our application.

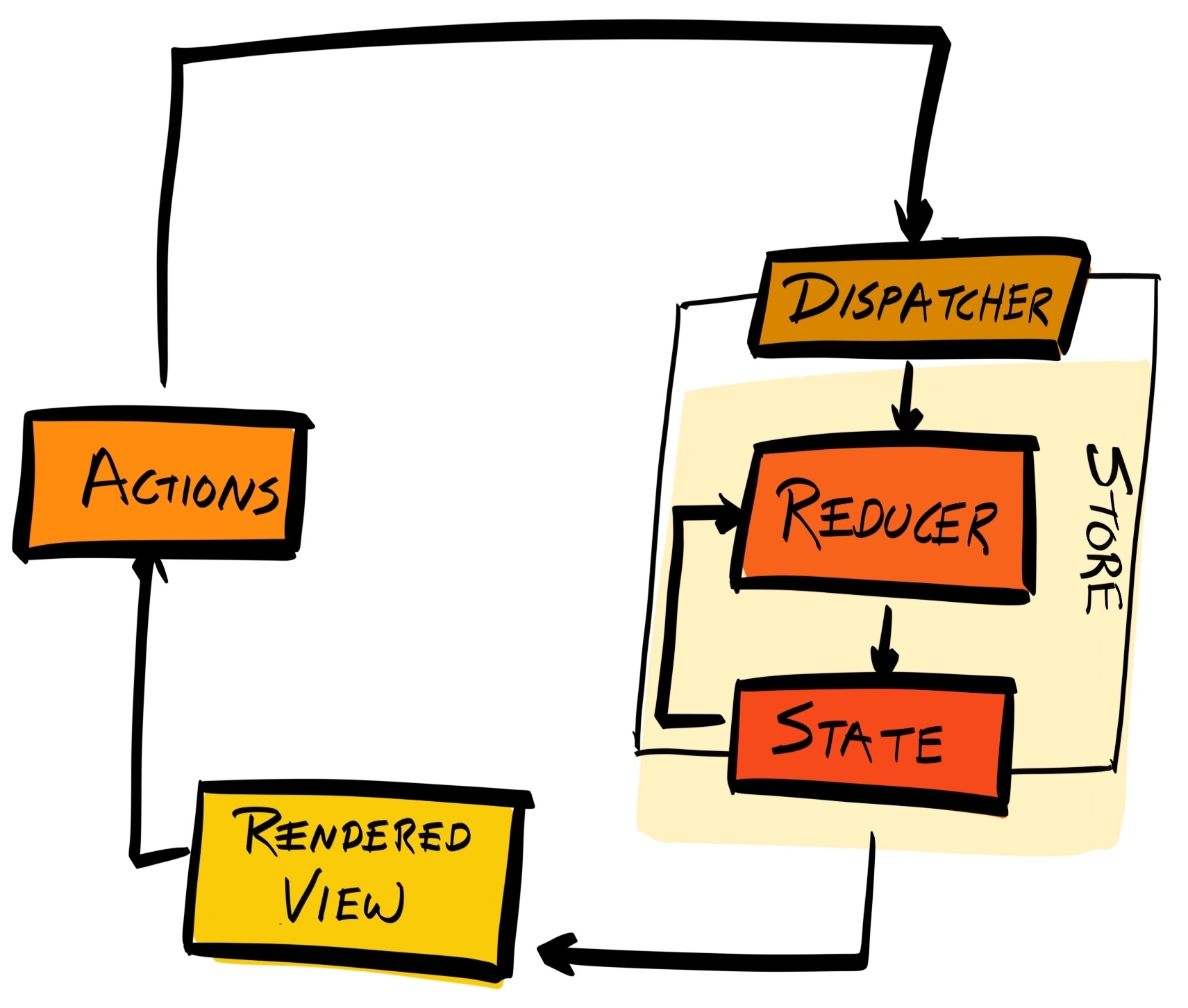

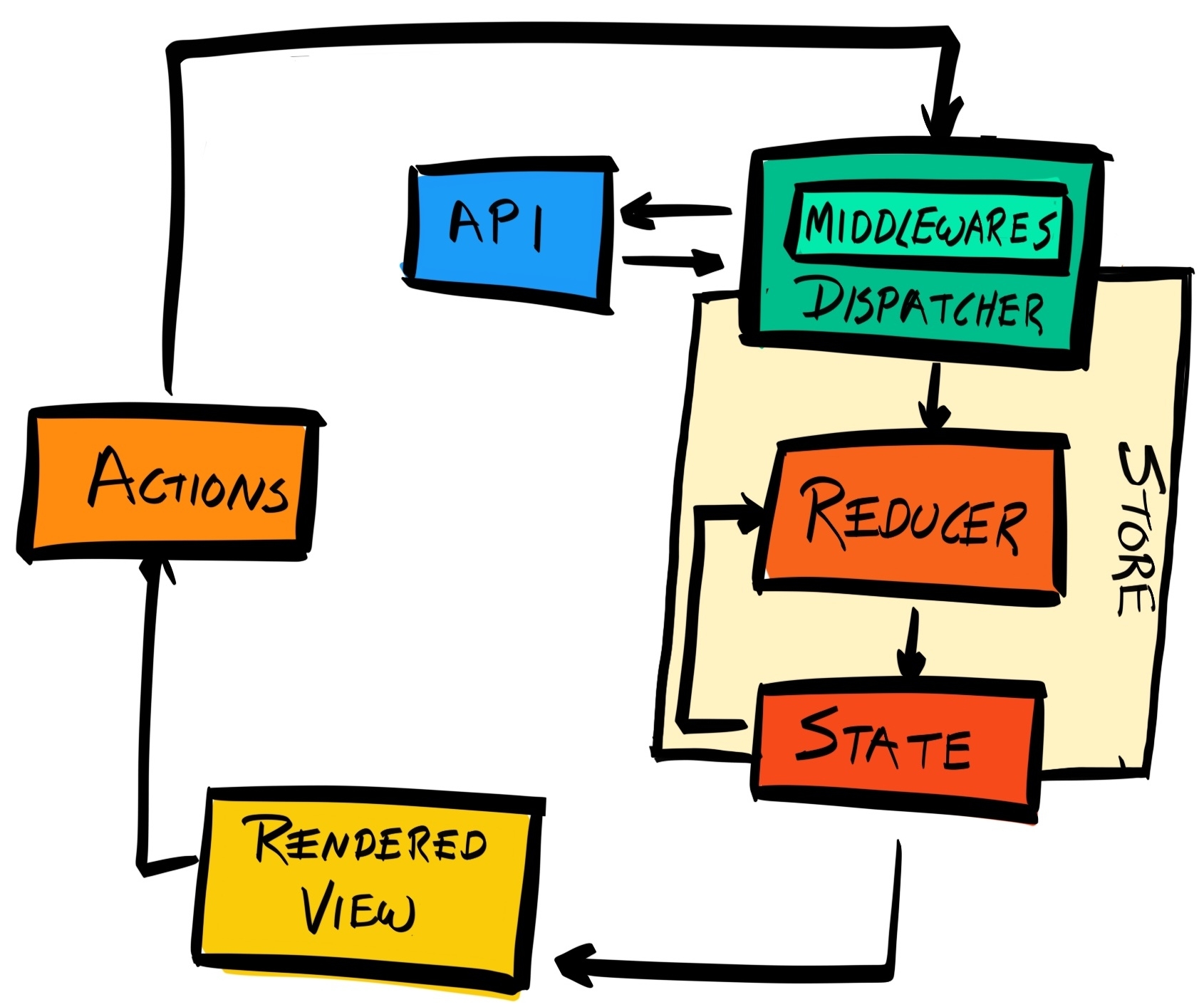

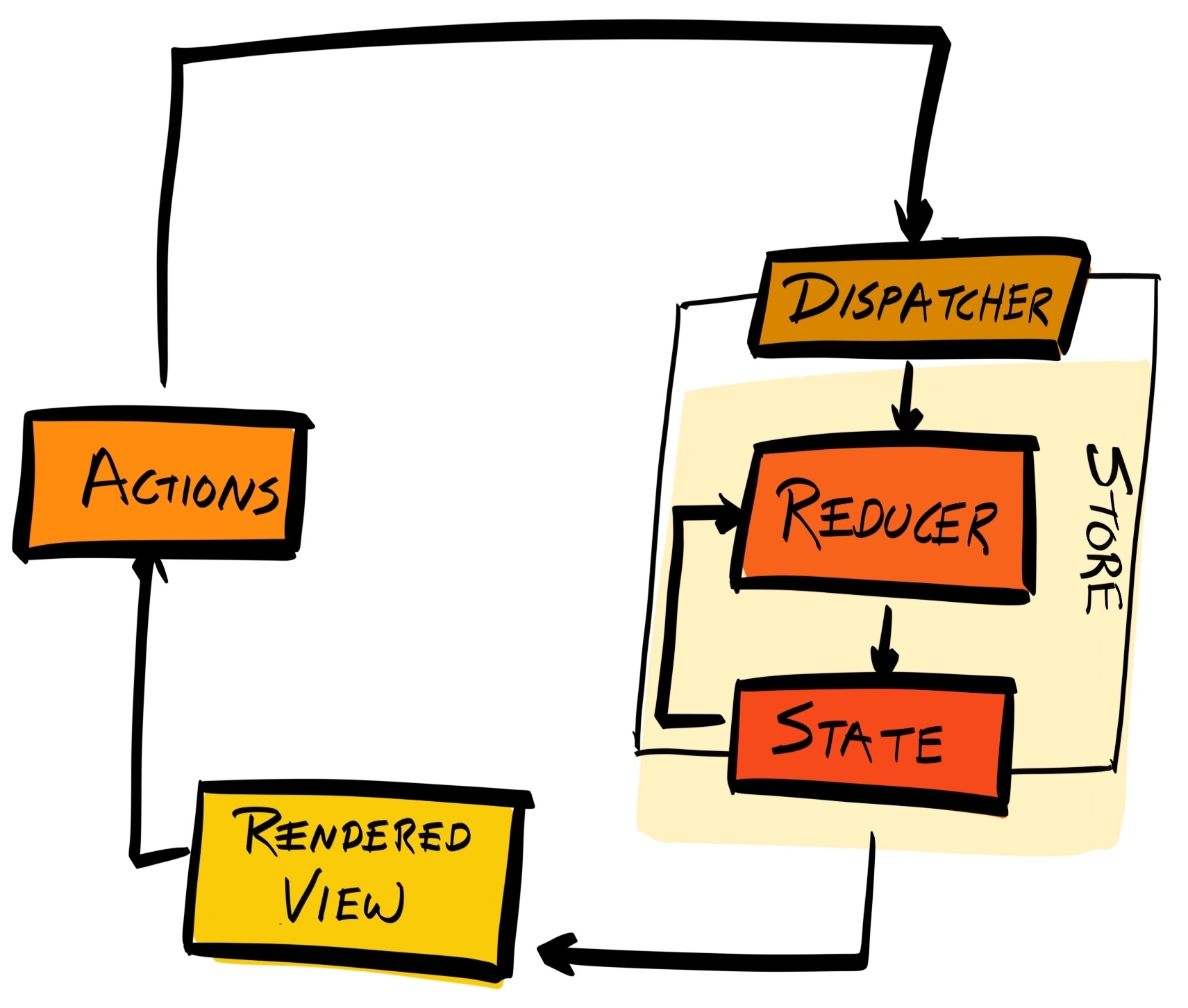

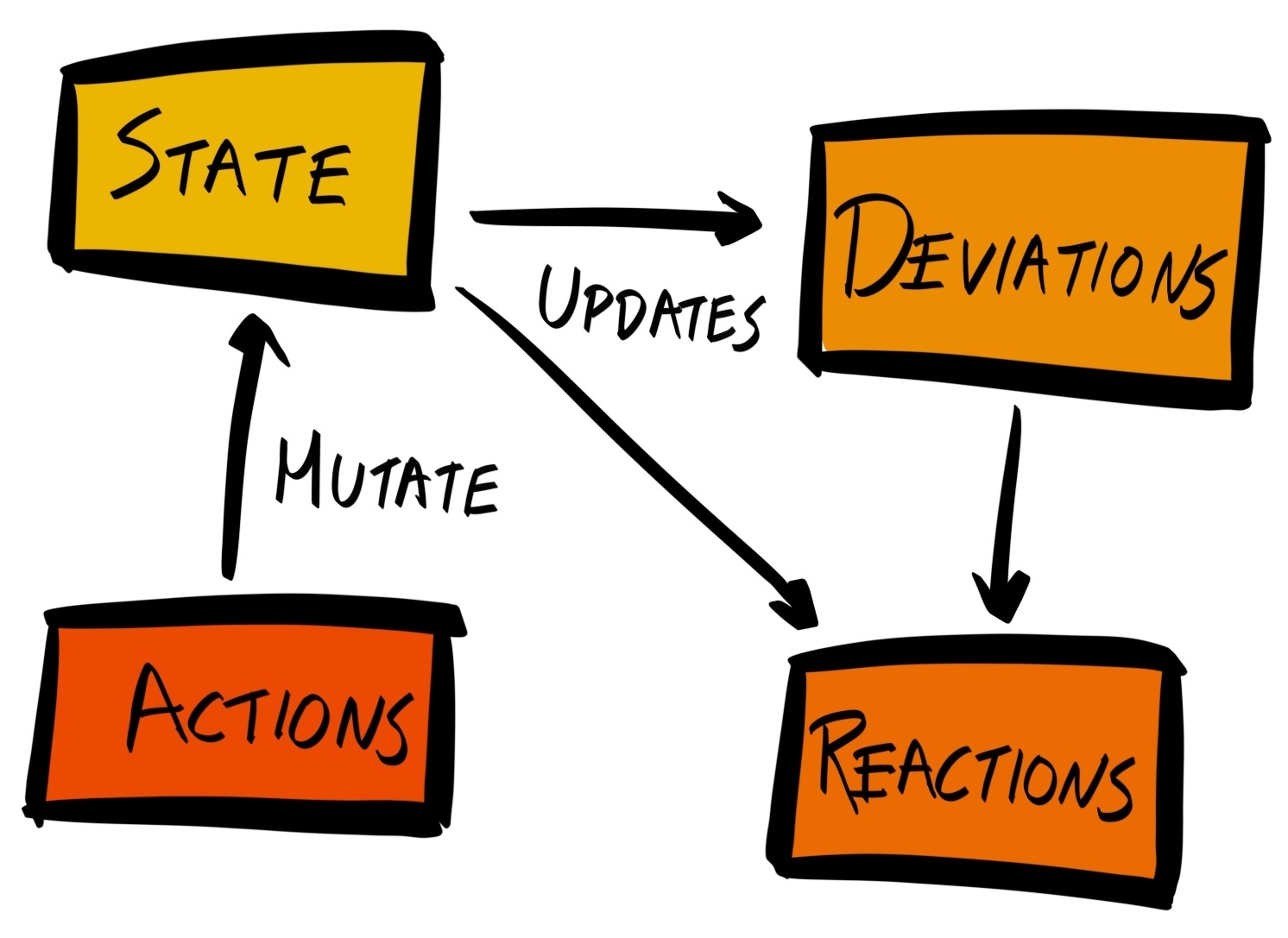

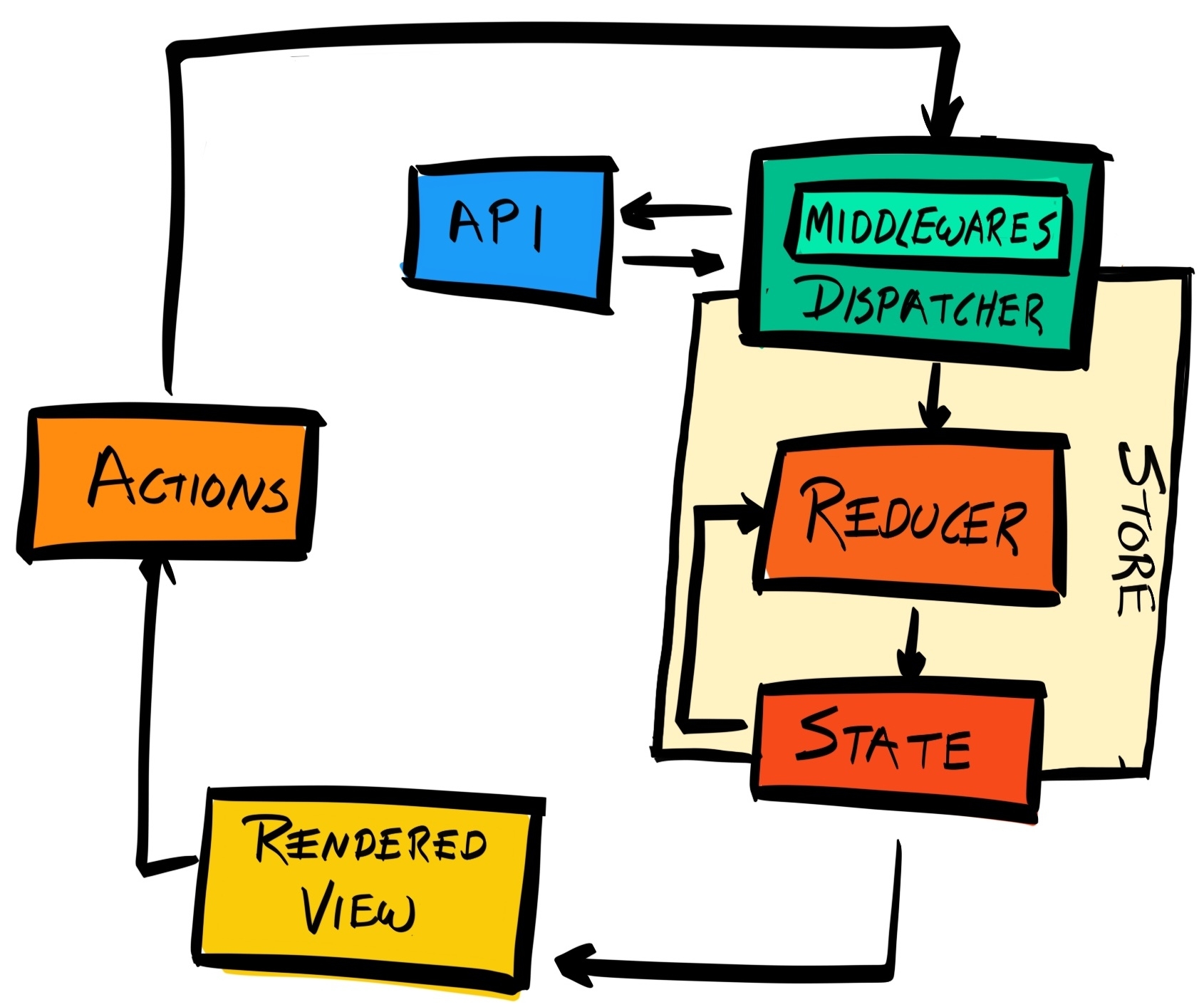

Chapter 16, Managing States with Redux, explains how to use Redux to keep the state of your application consistent.

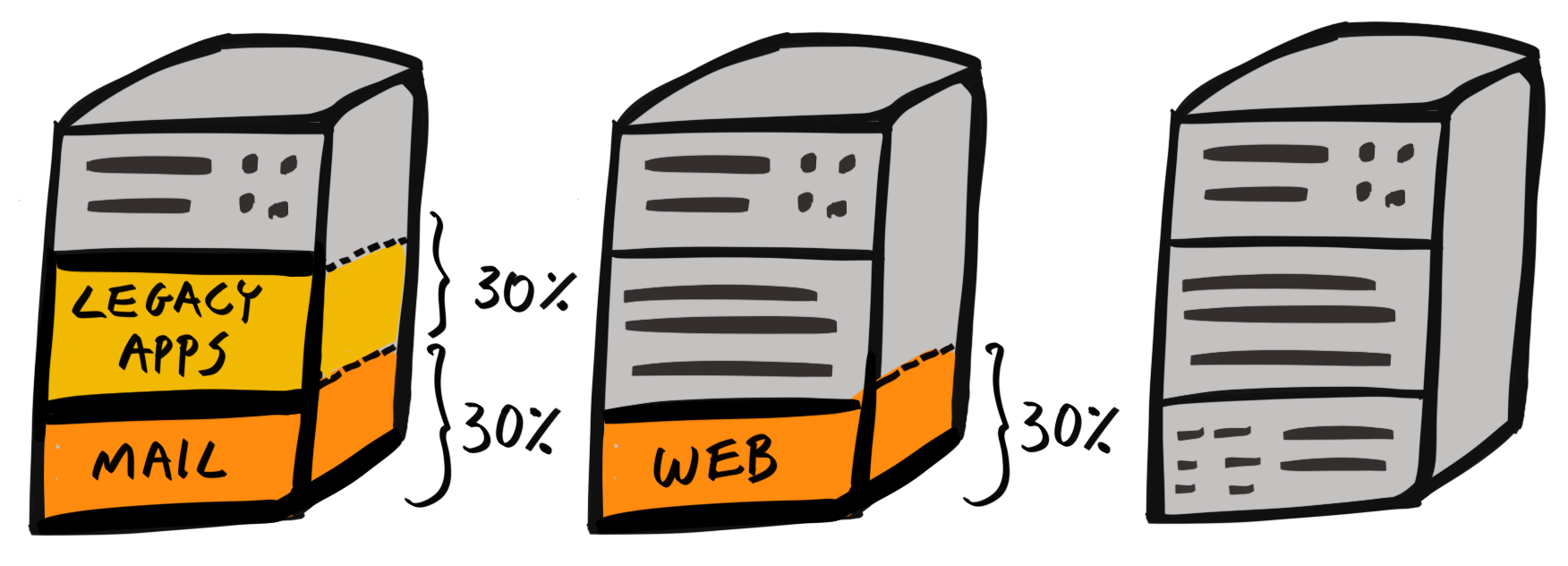

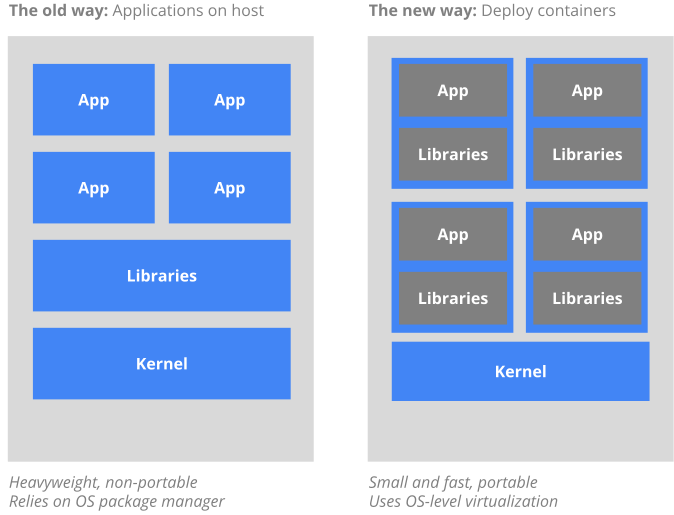

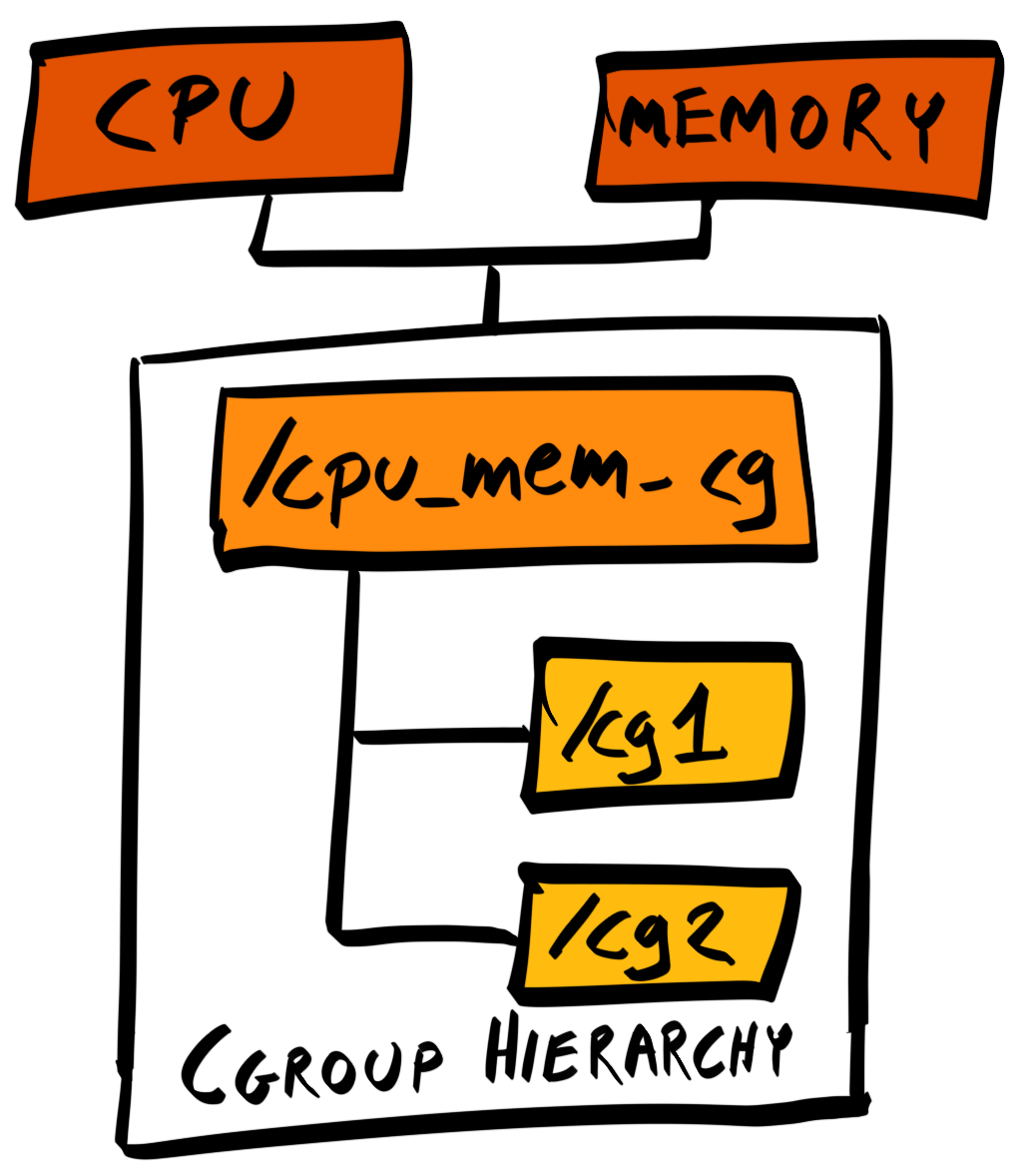

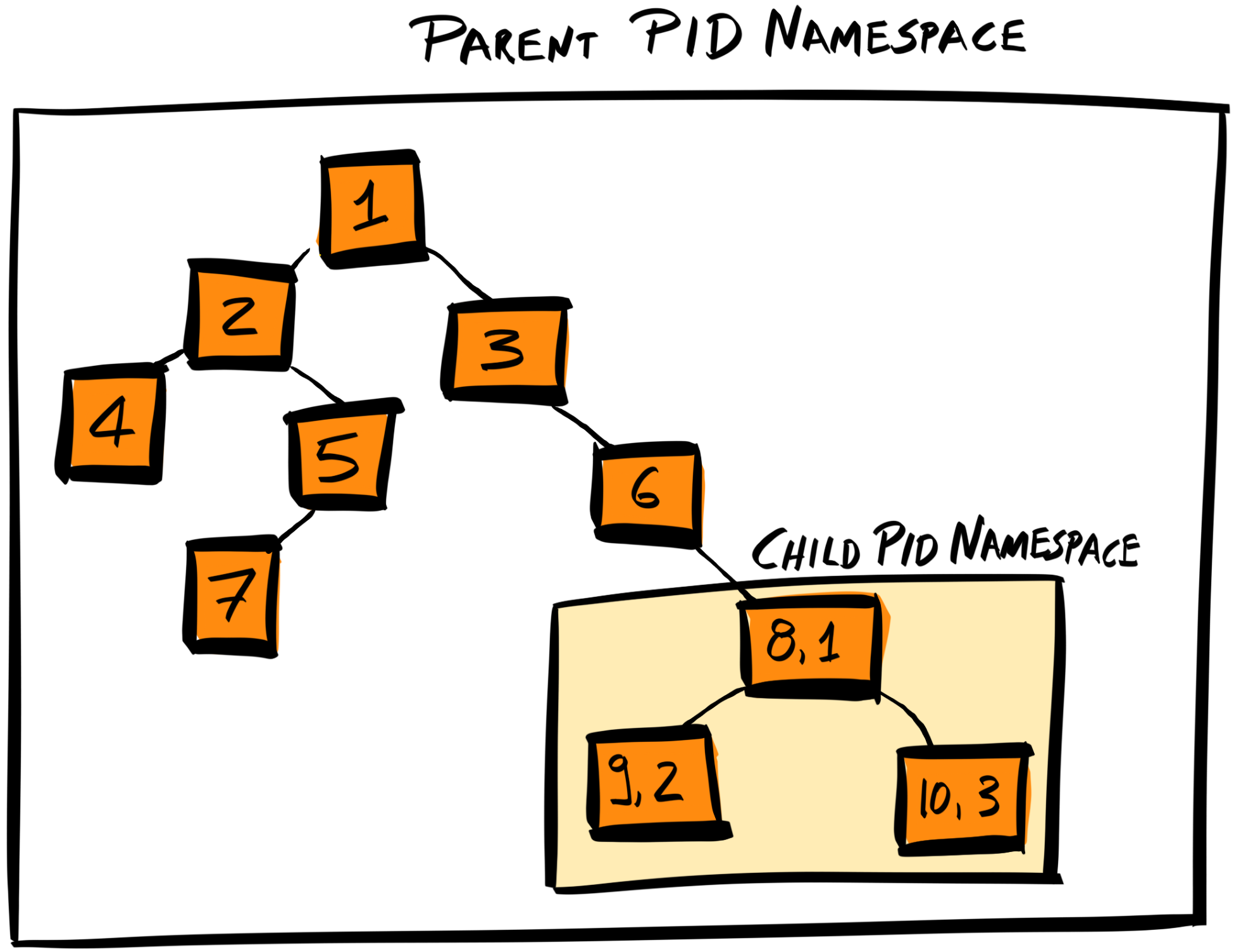

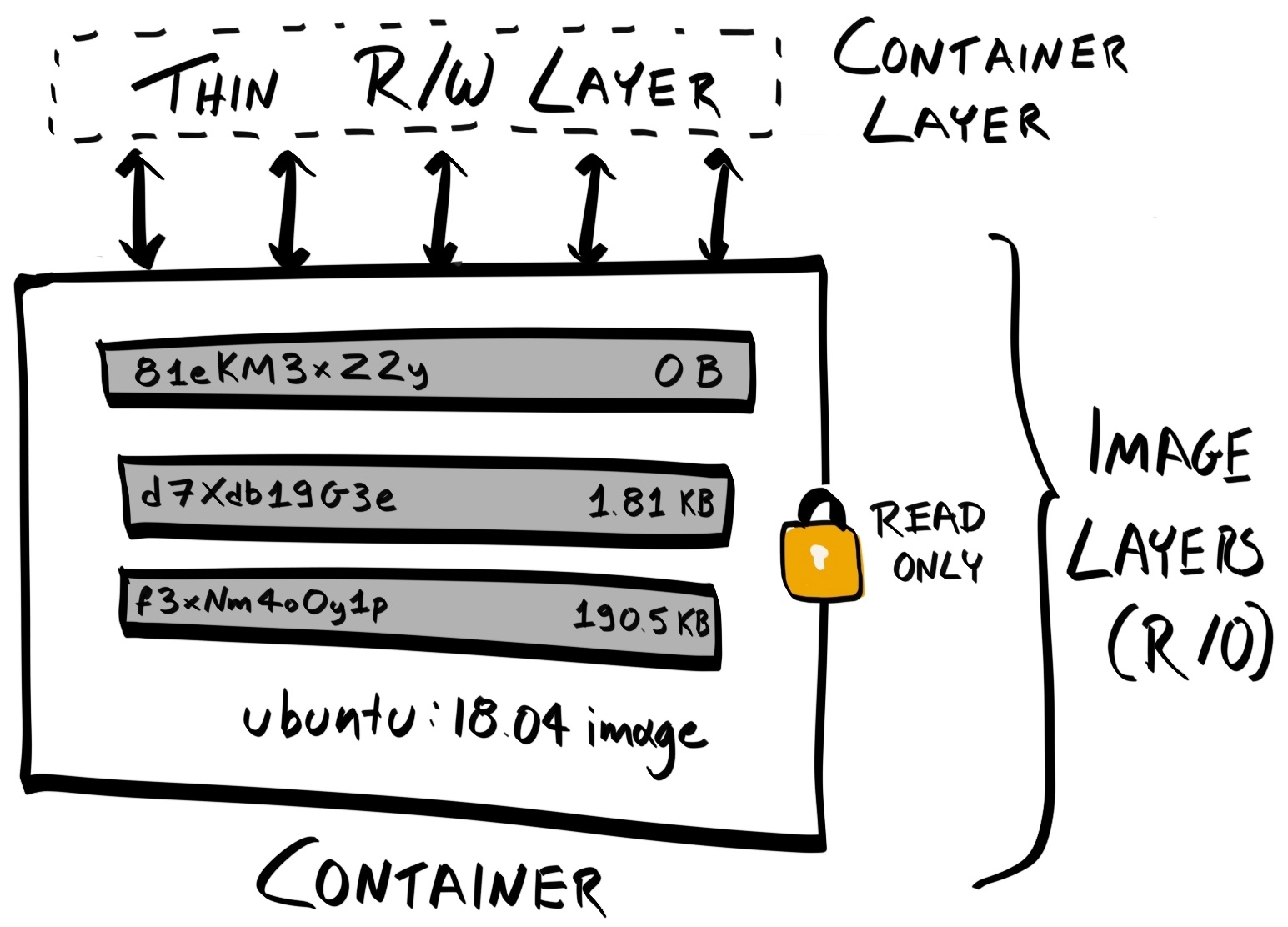

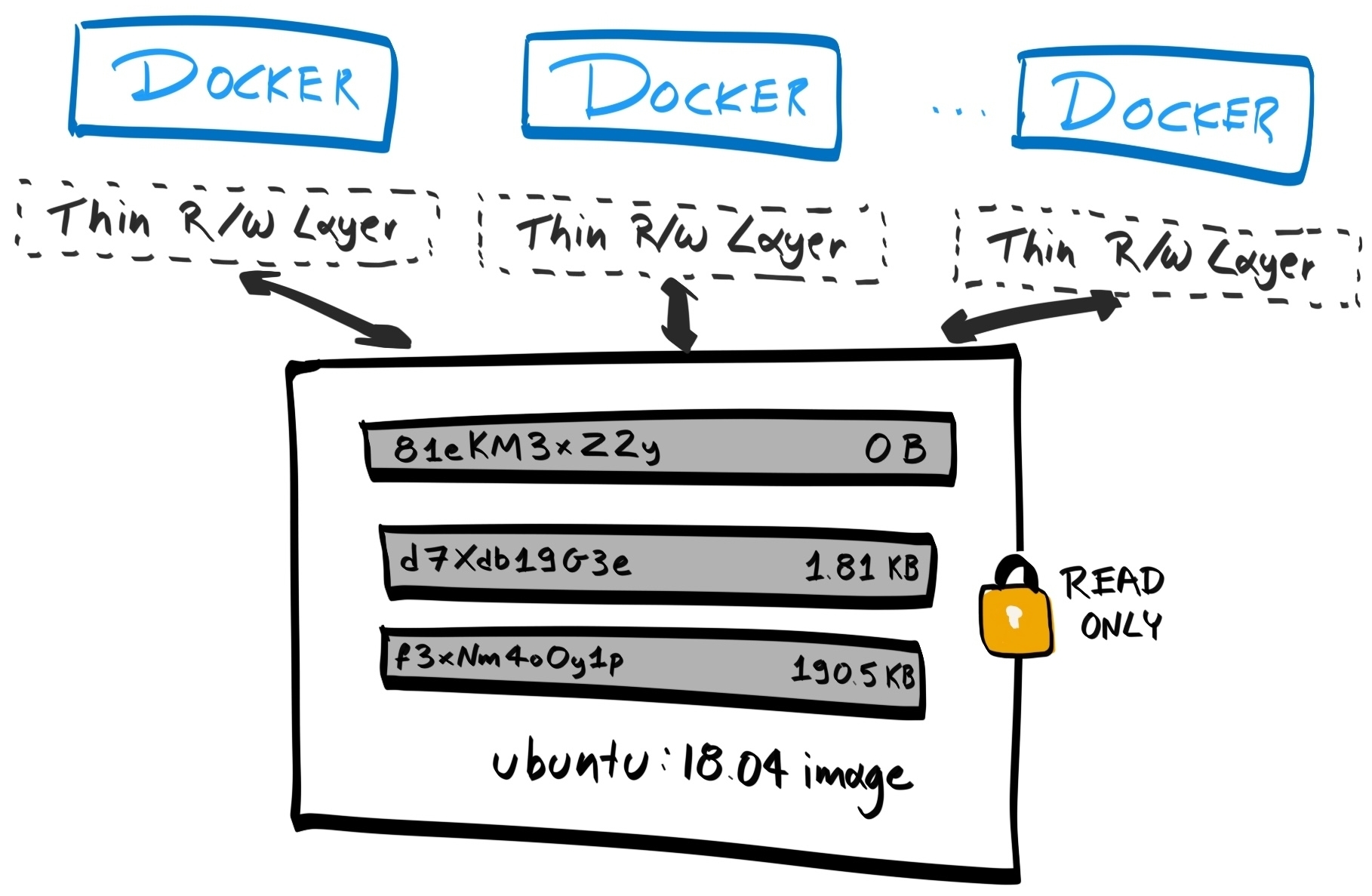

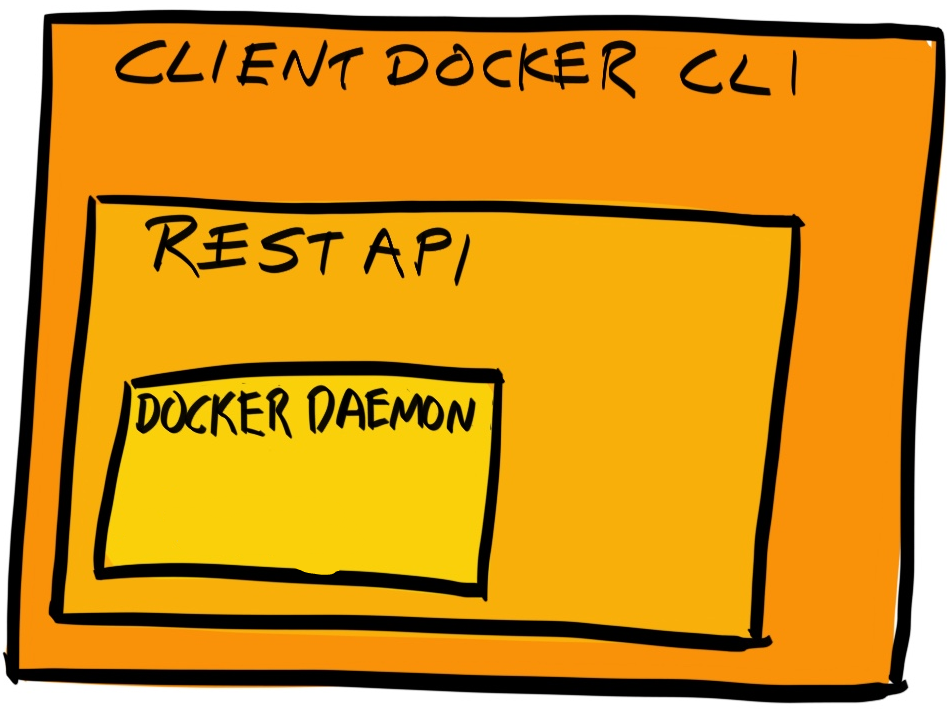

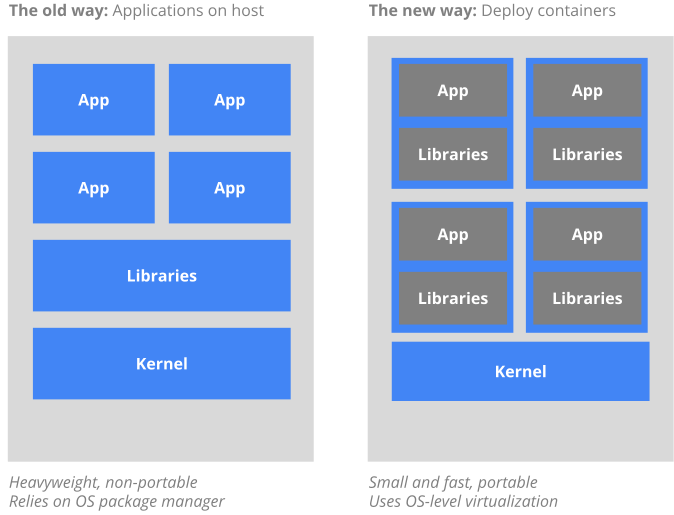

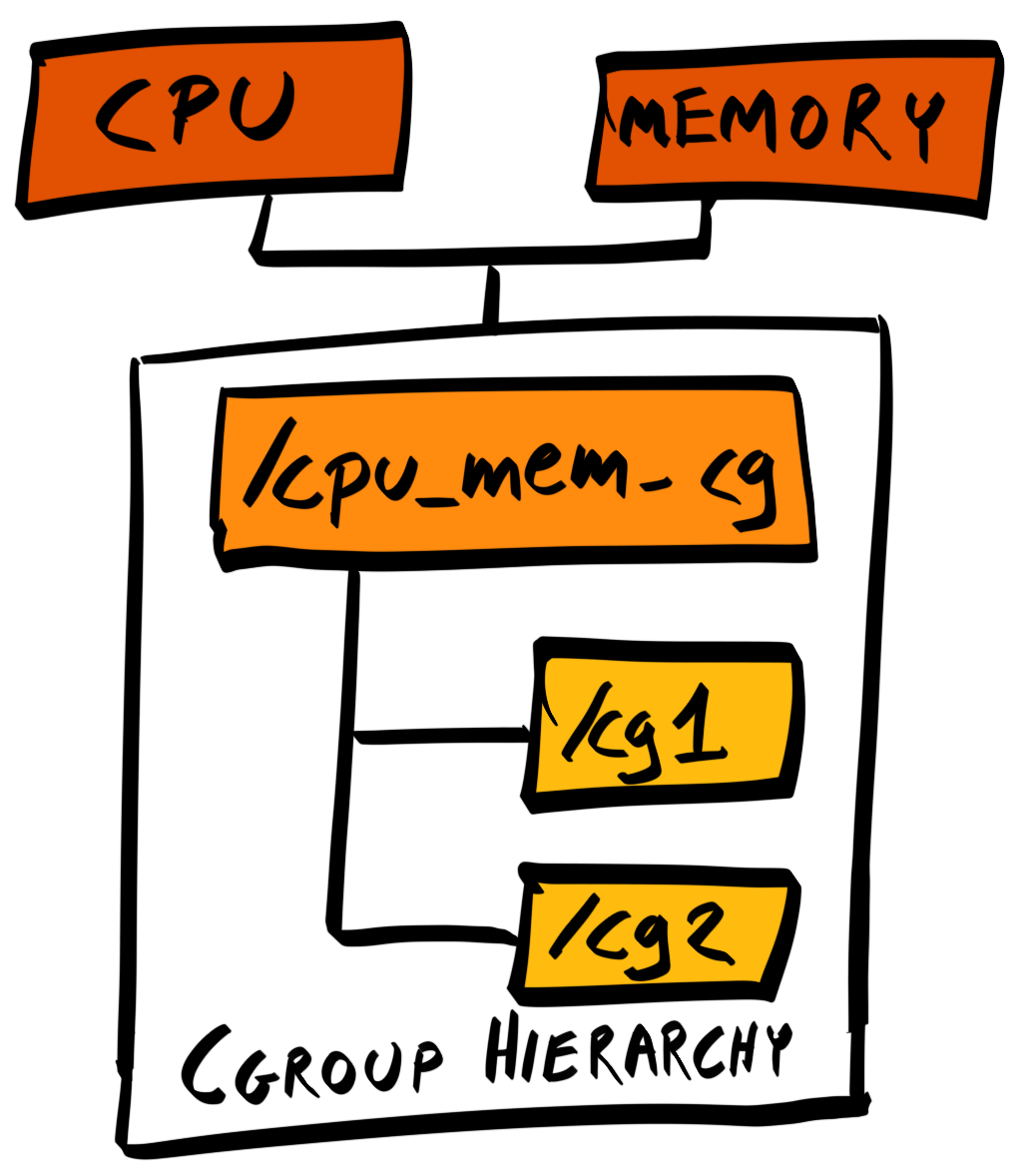

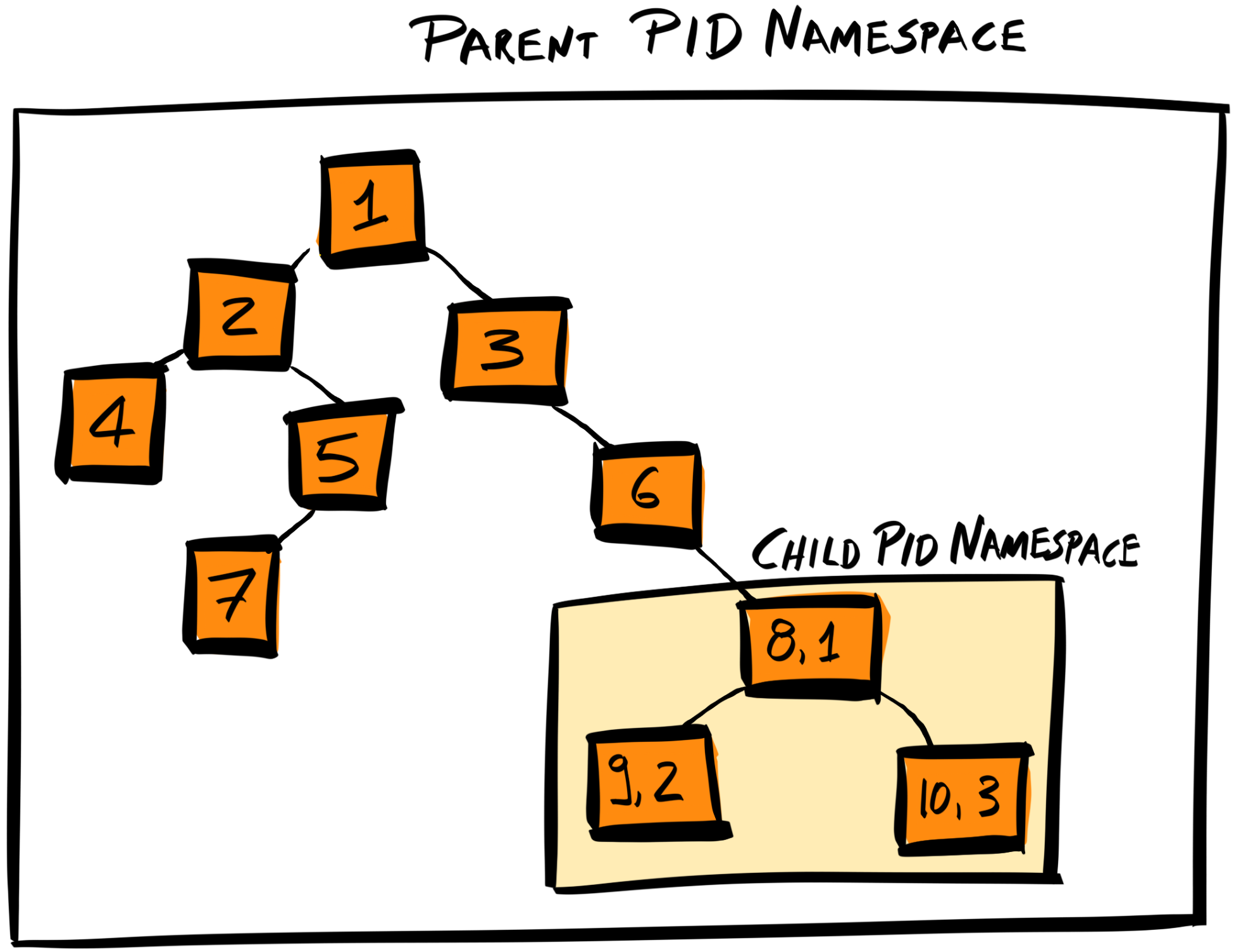

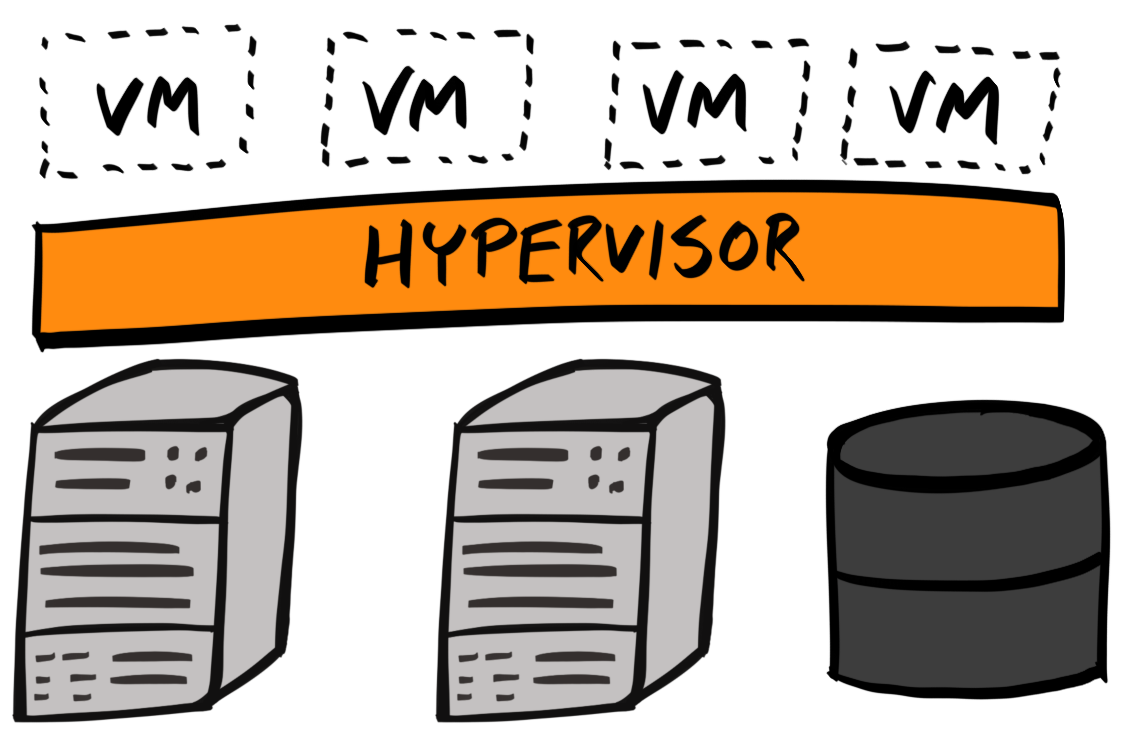

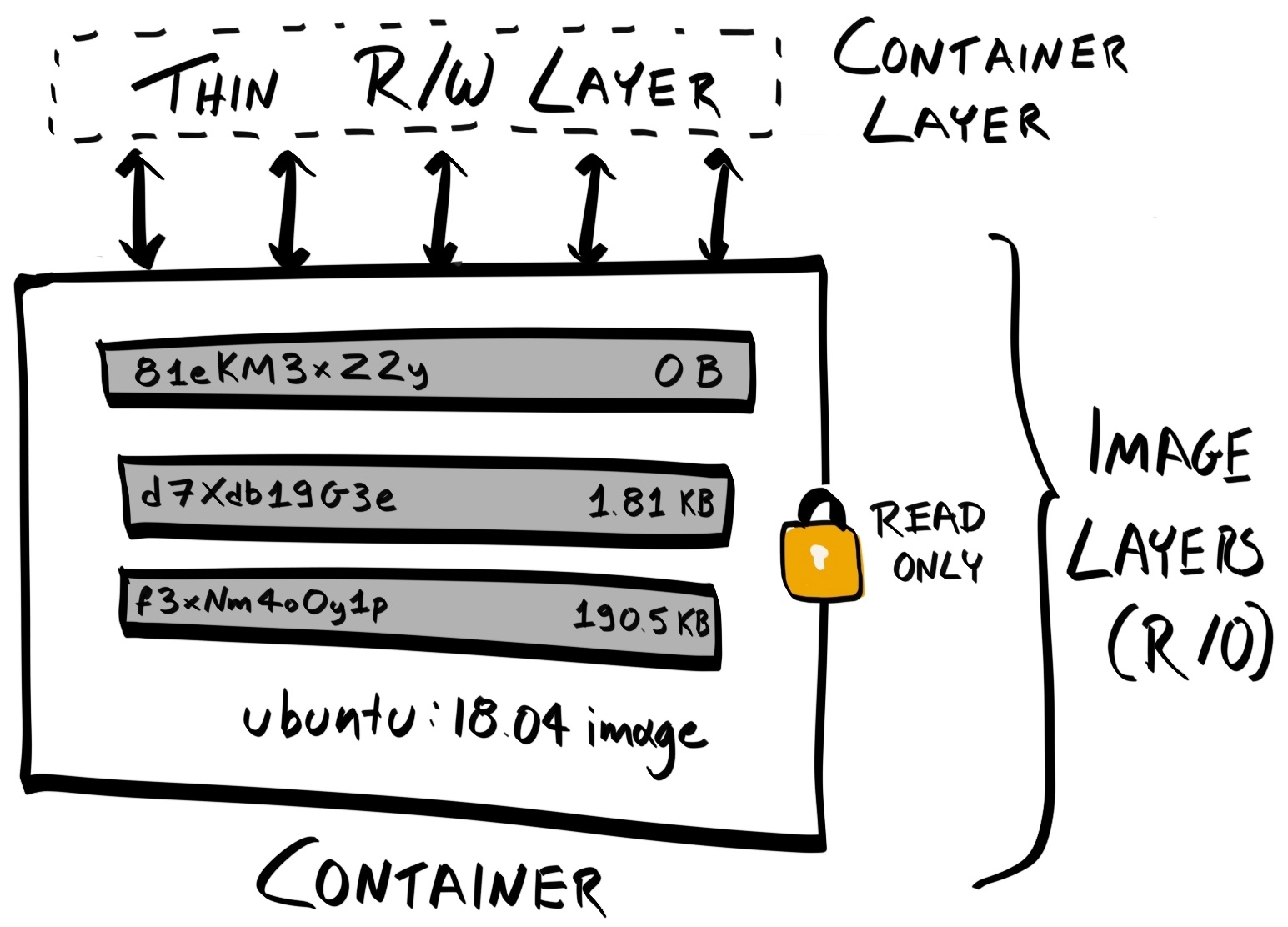

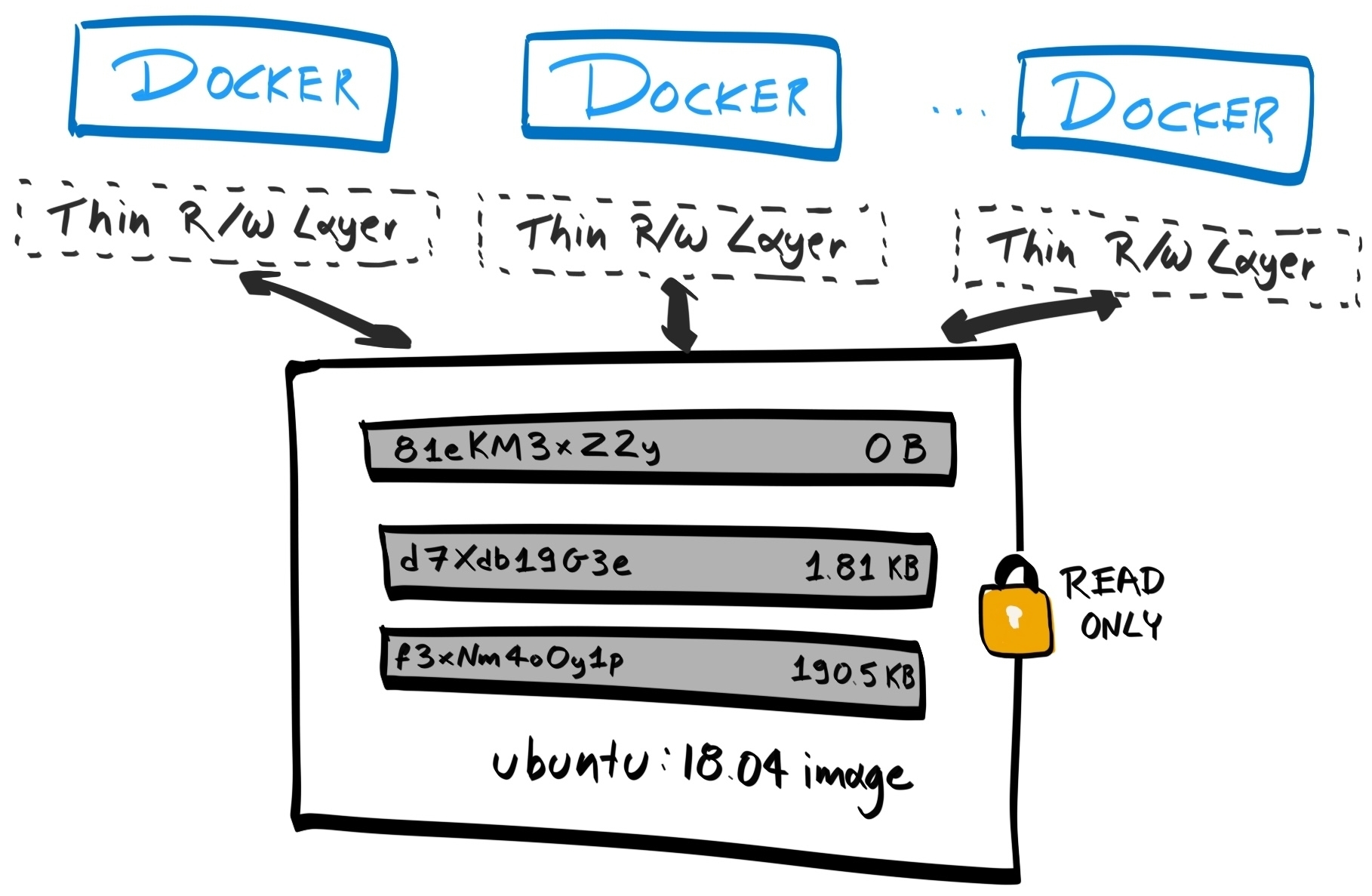

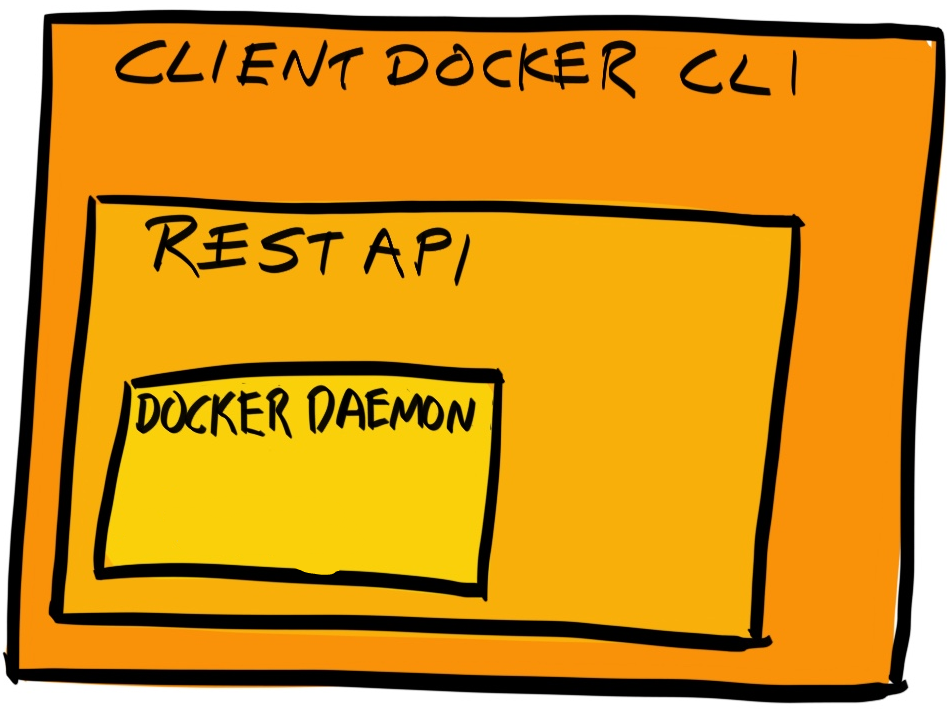

Chapter 17, Migrating to Docker, migrates our application to run inside Docker containers. Initially, you'll learn about control groups and namespaces and how they enable containers to work. Then you'll write your own Dockerfiles and build and optimize your Docker images.

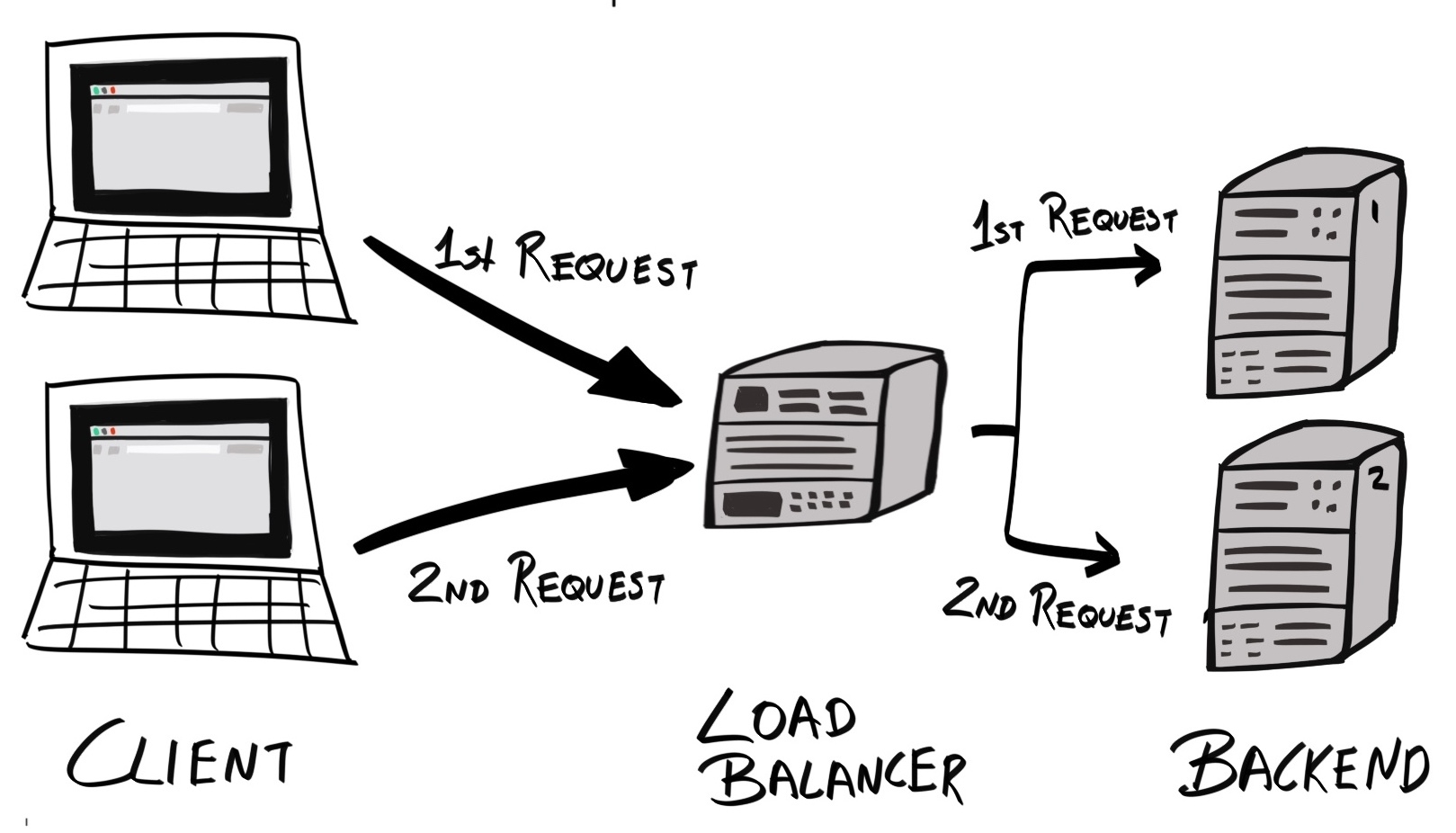

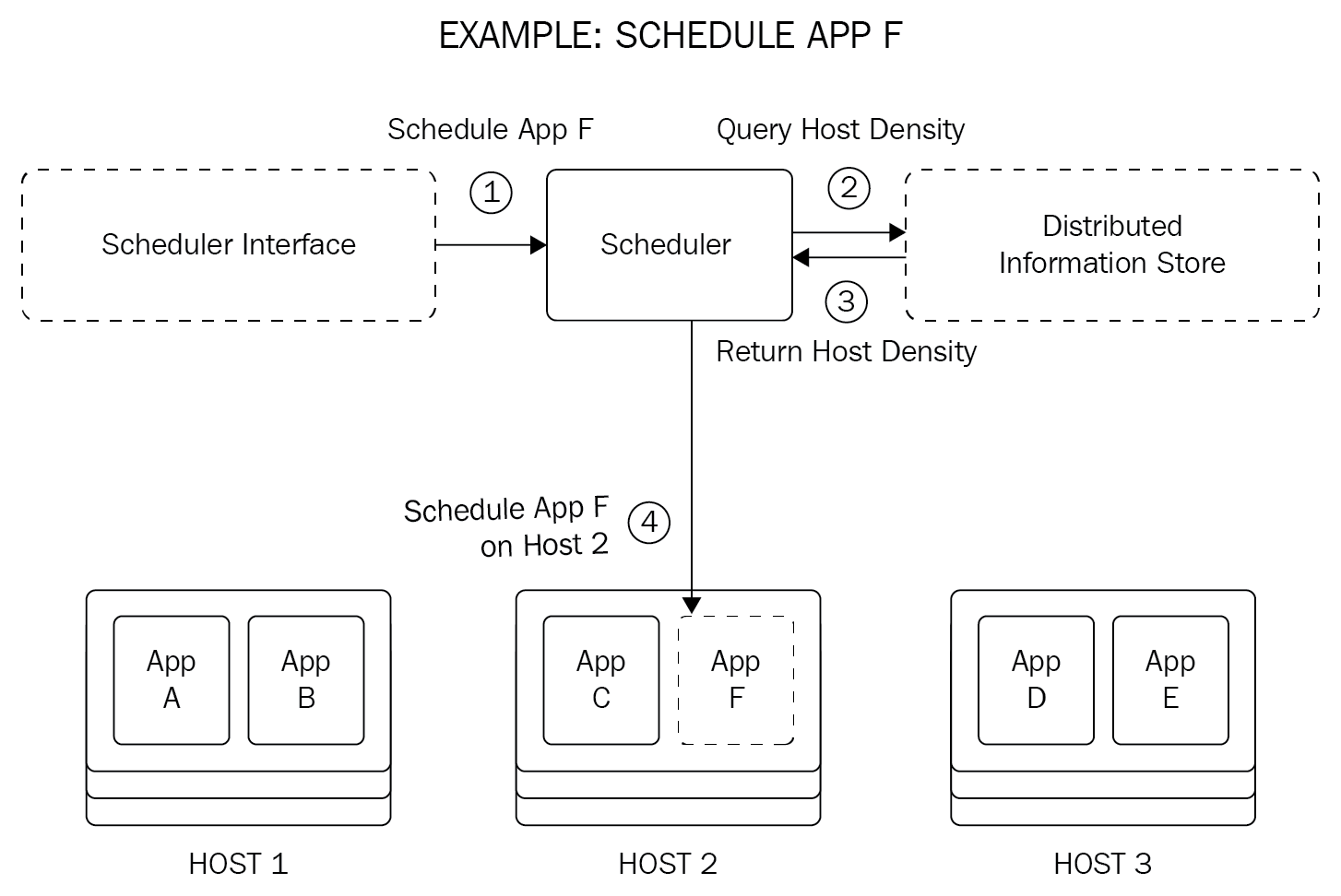

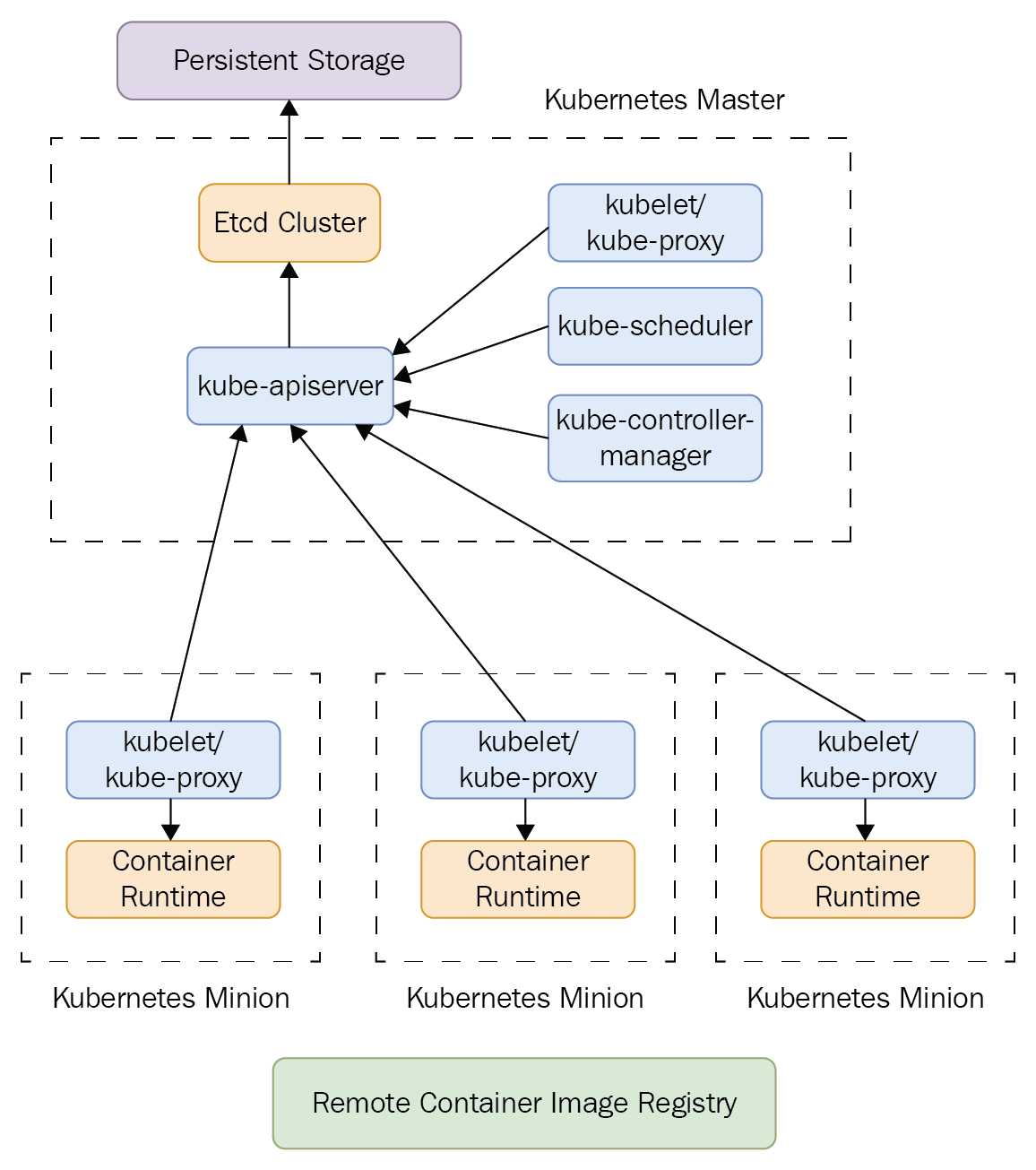

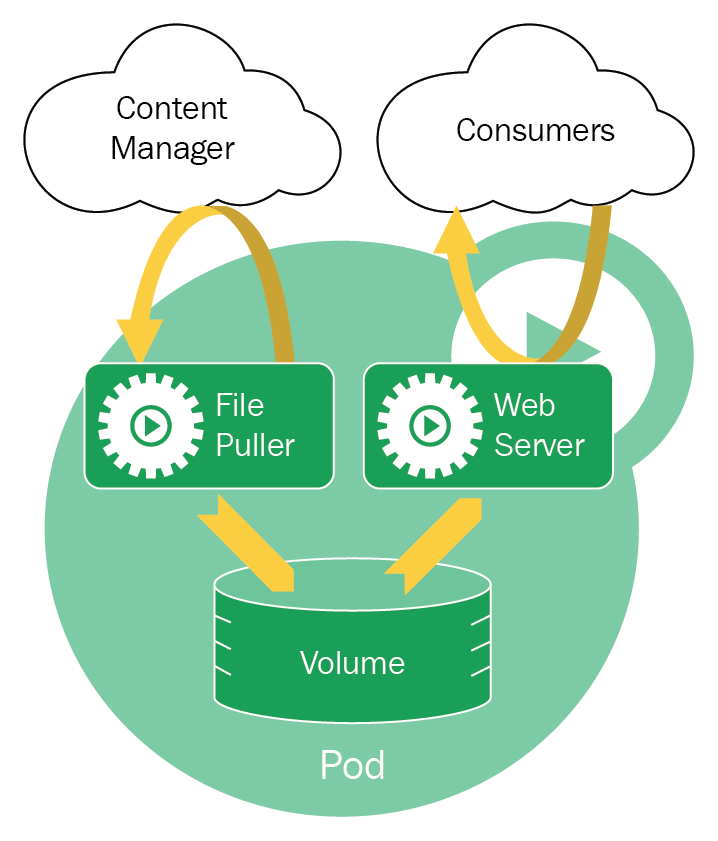

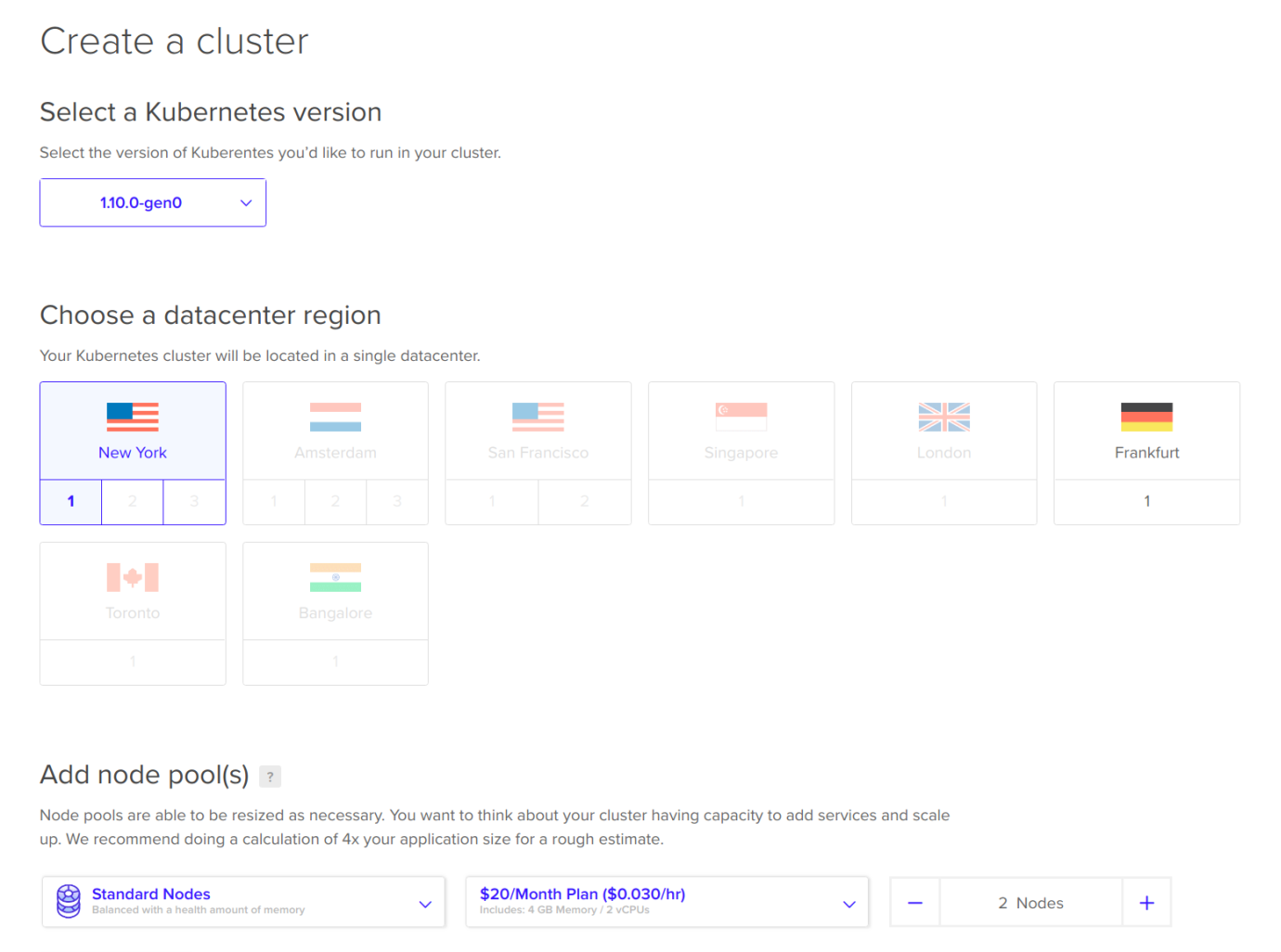

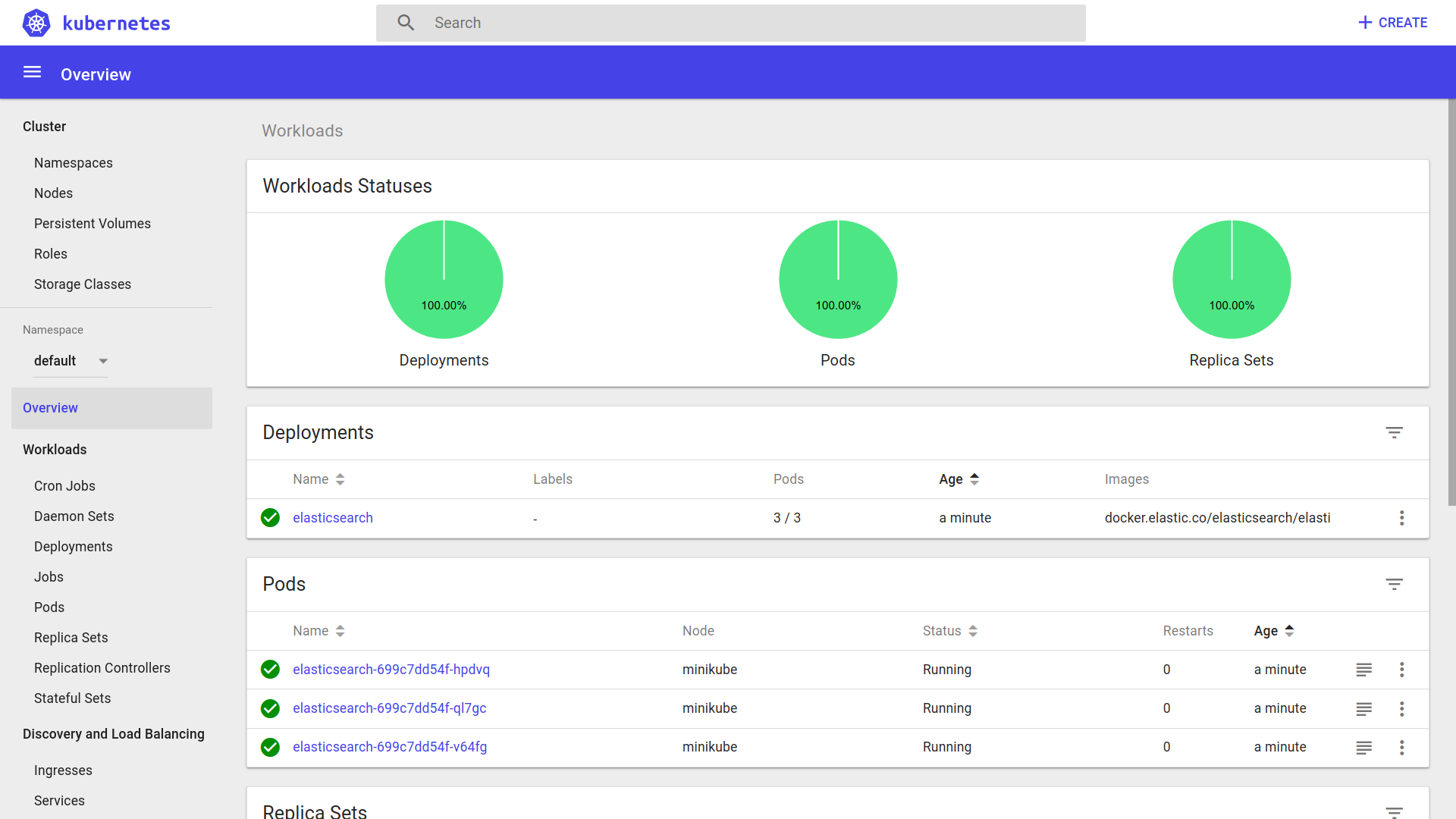

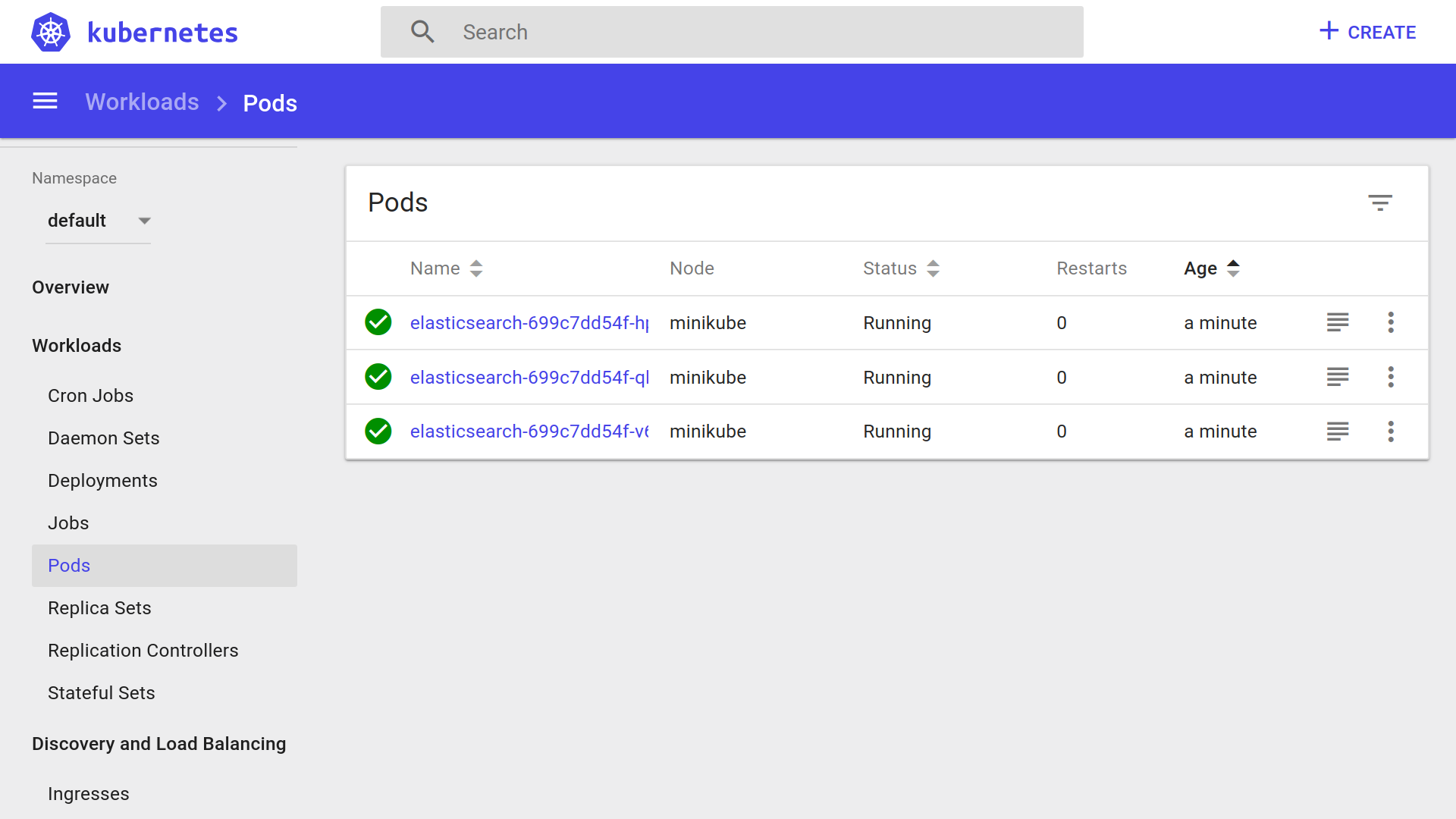

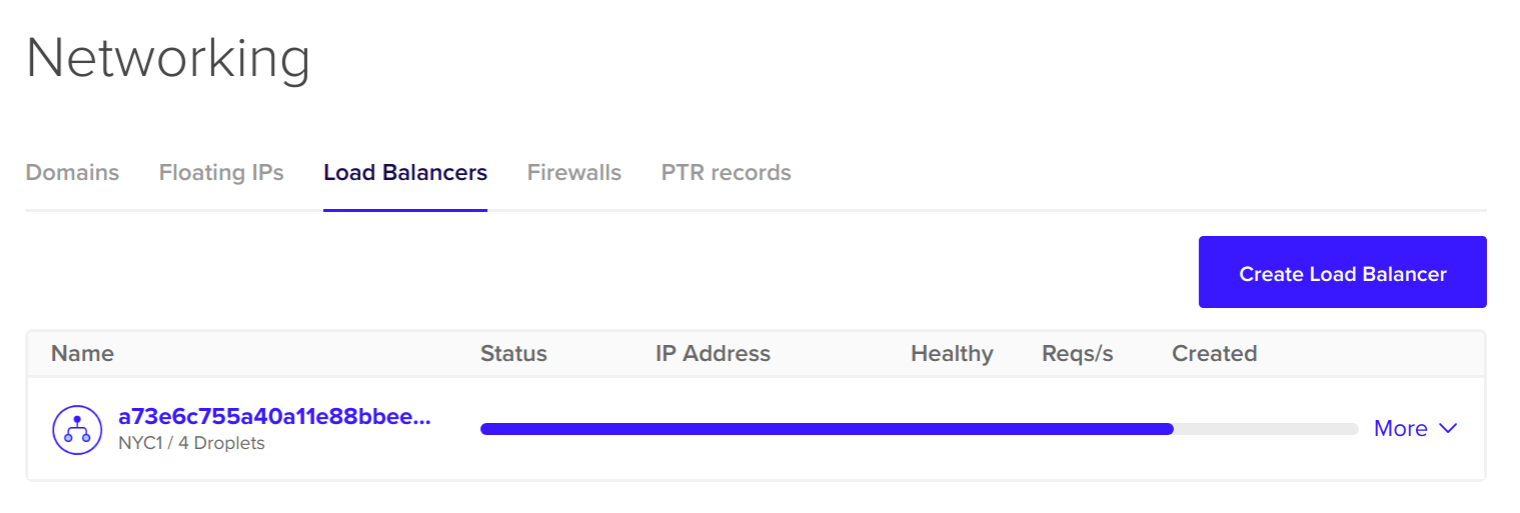

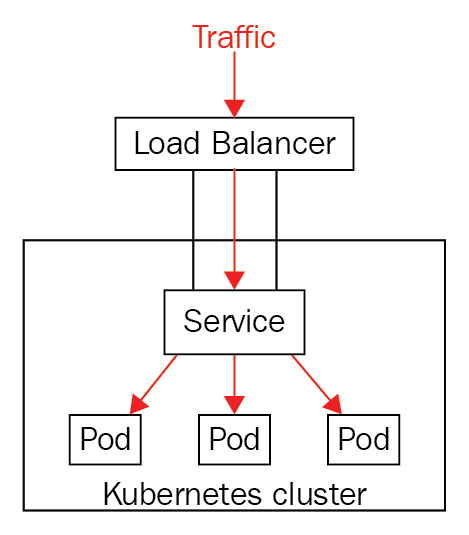

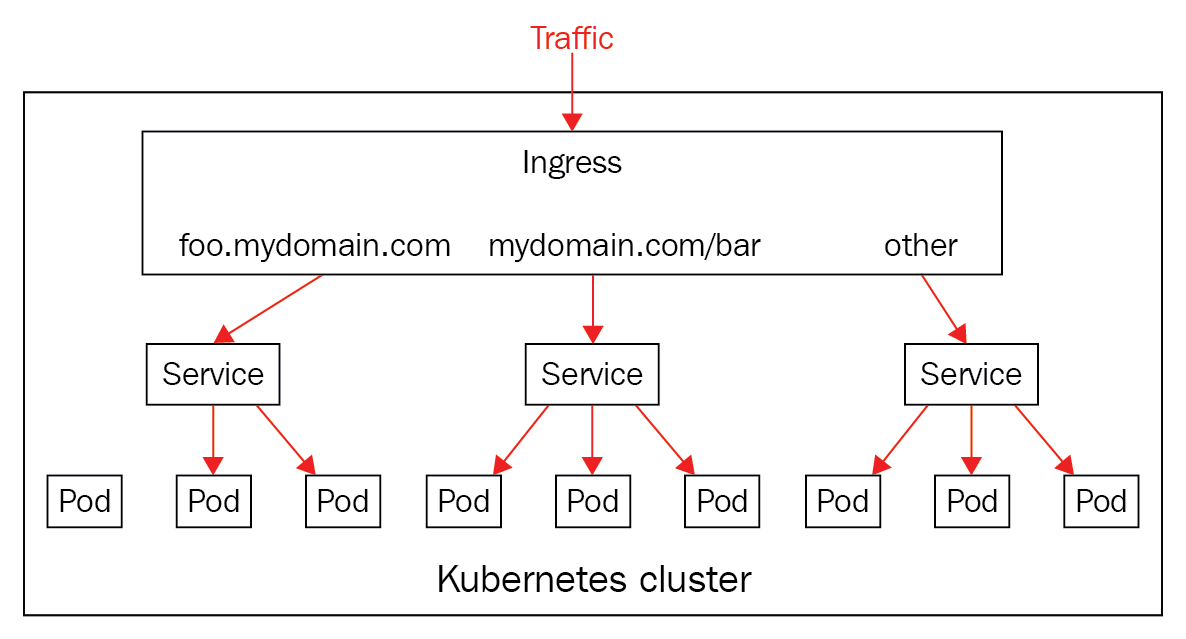

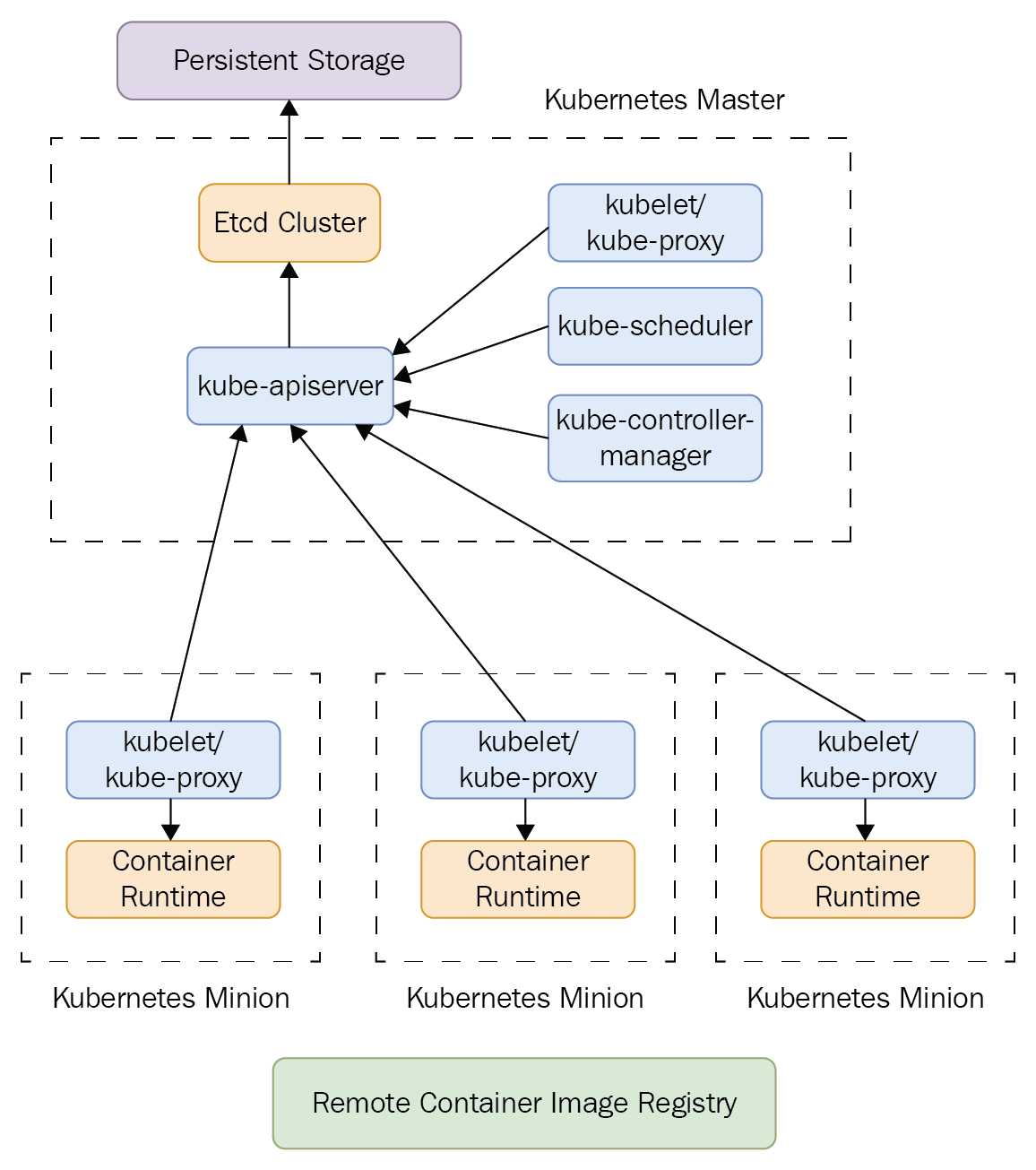

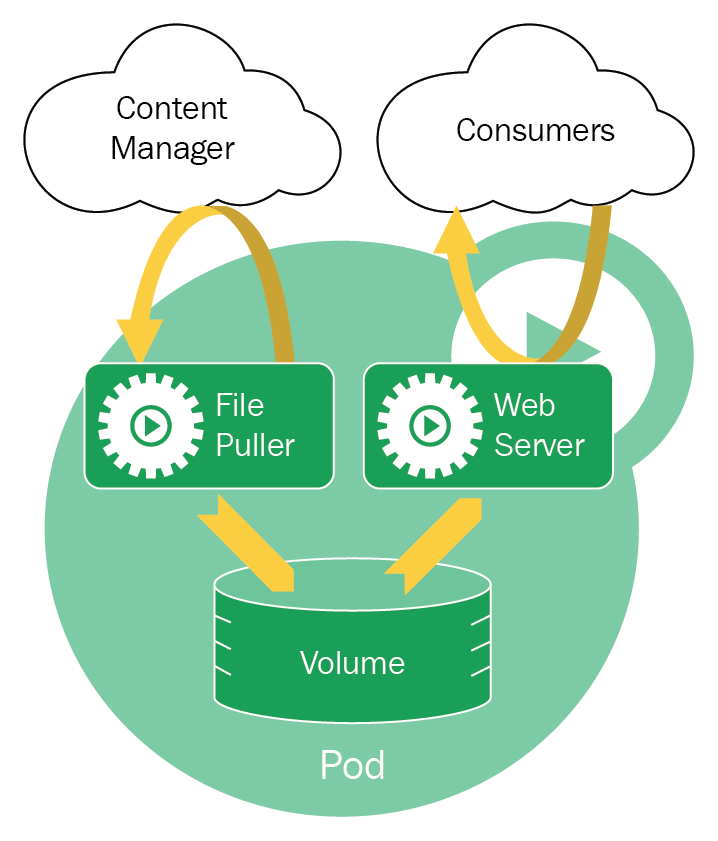

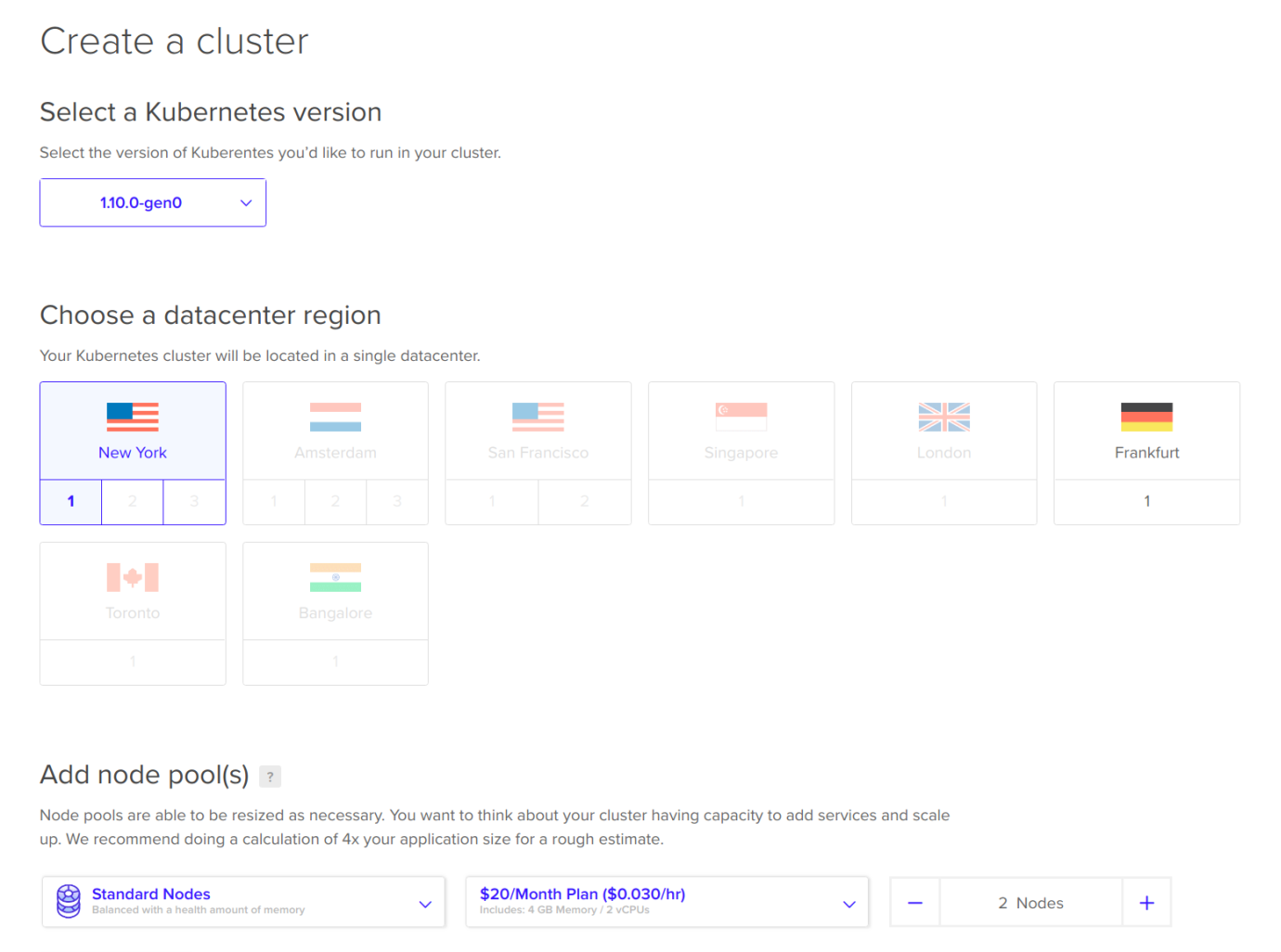

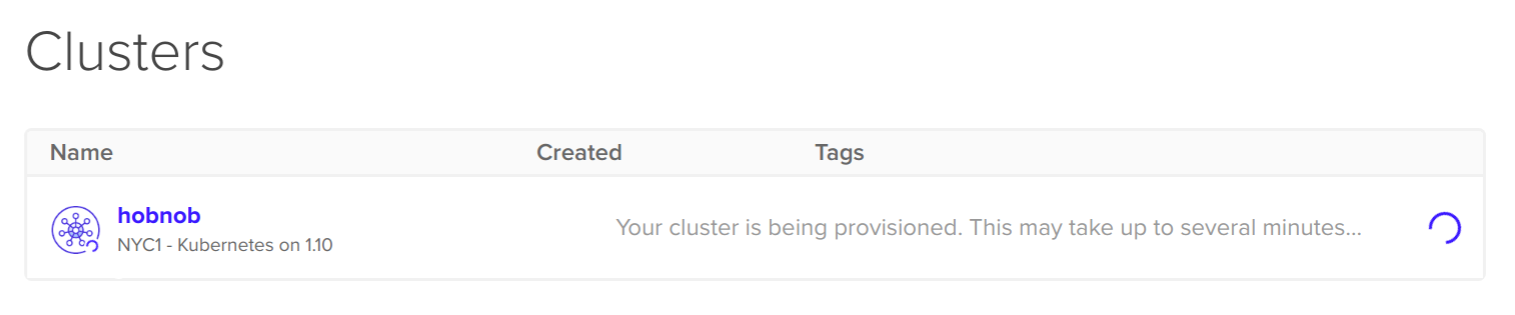

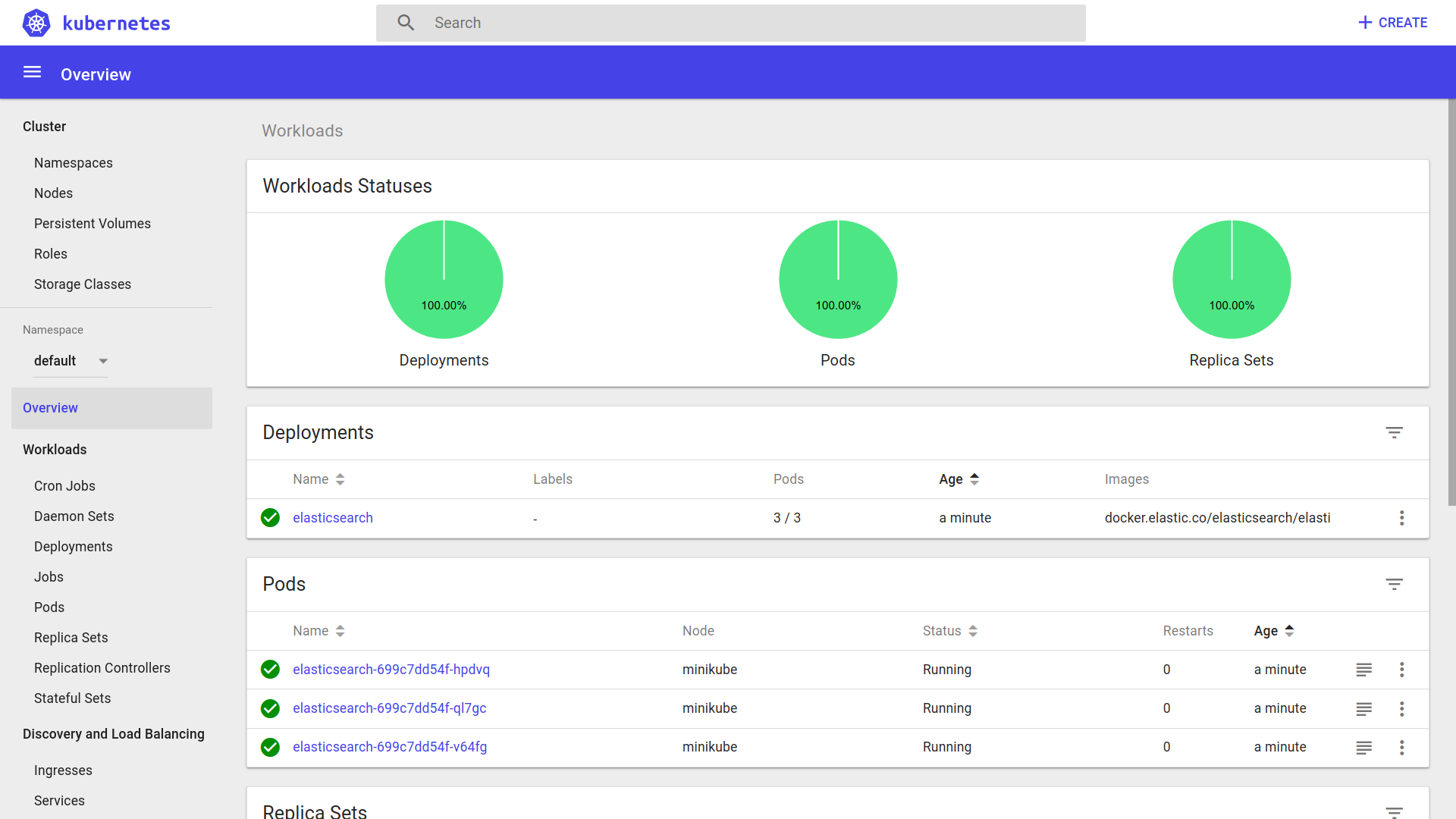

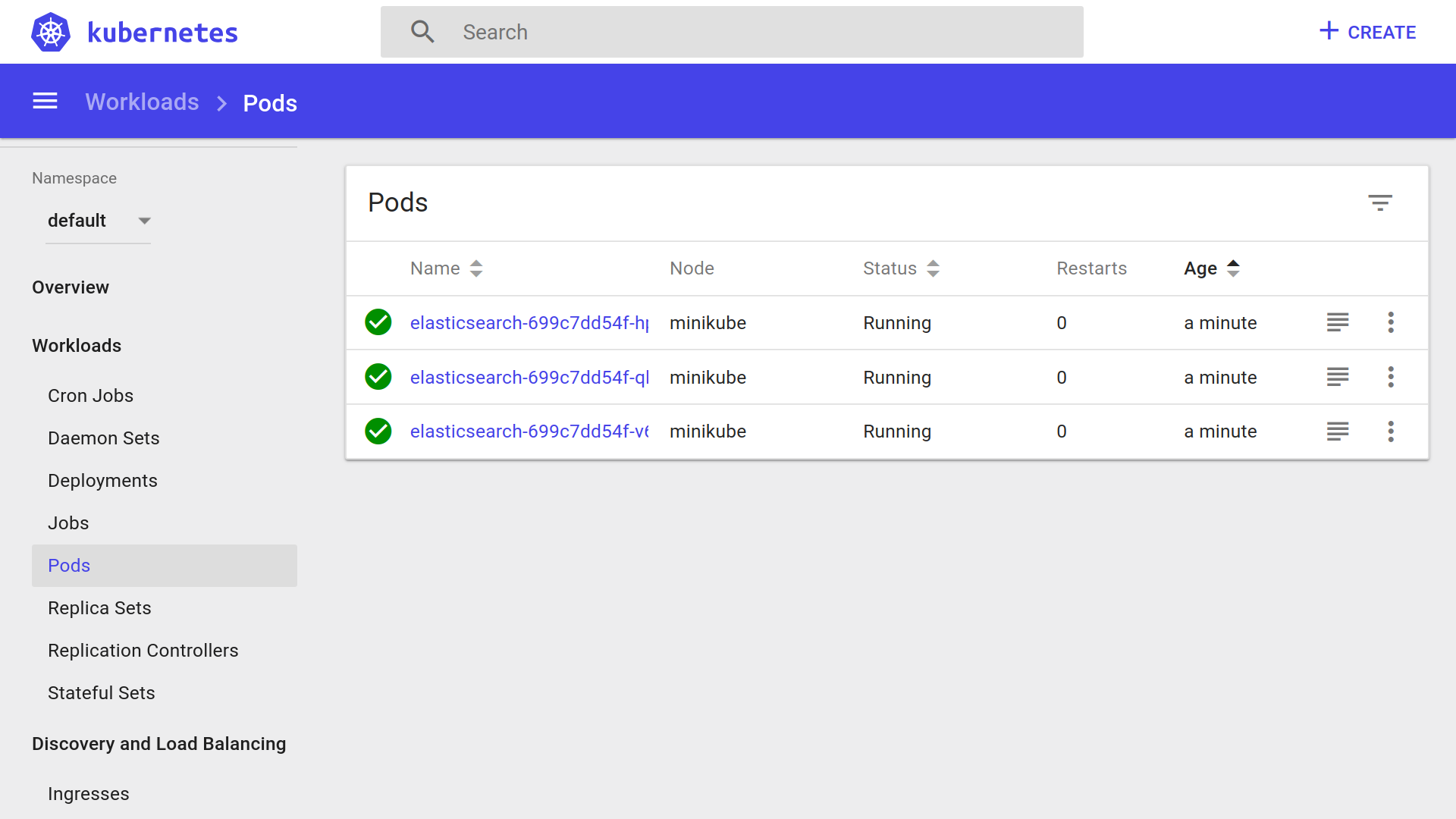

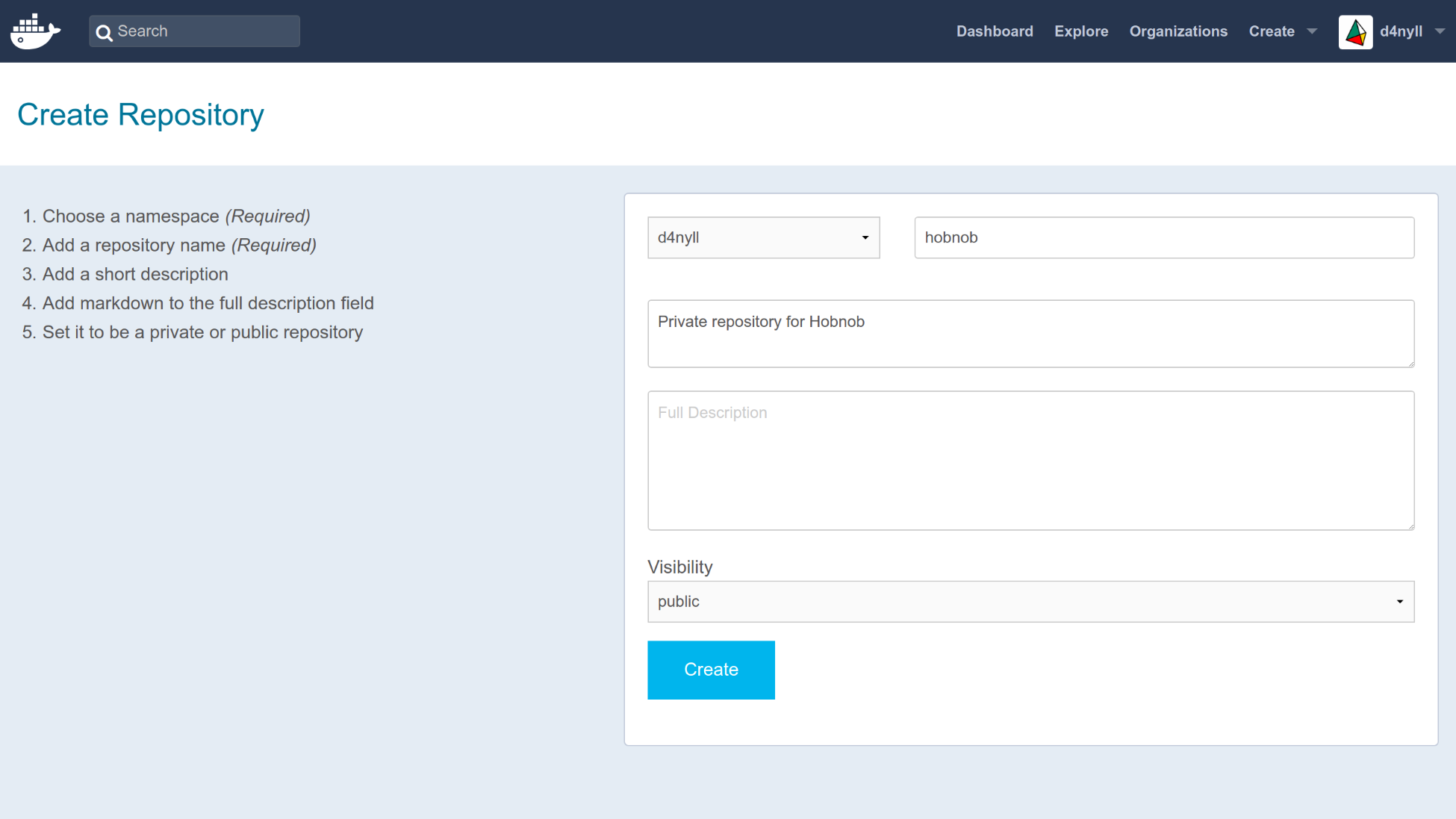

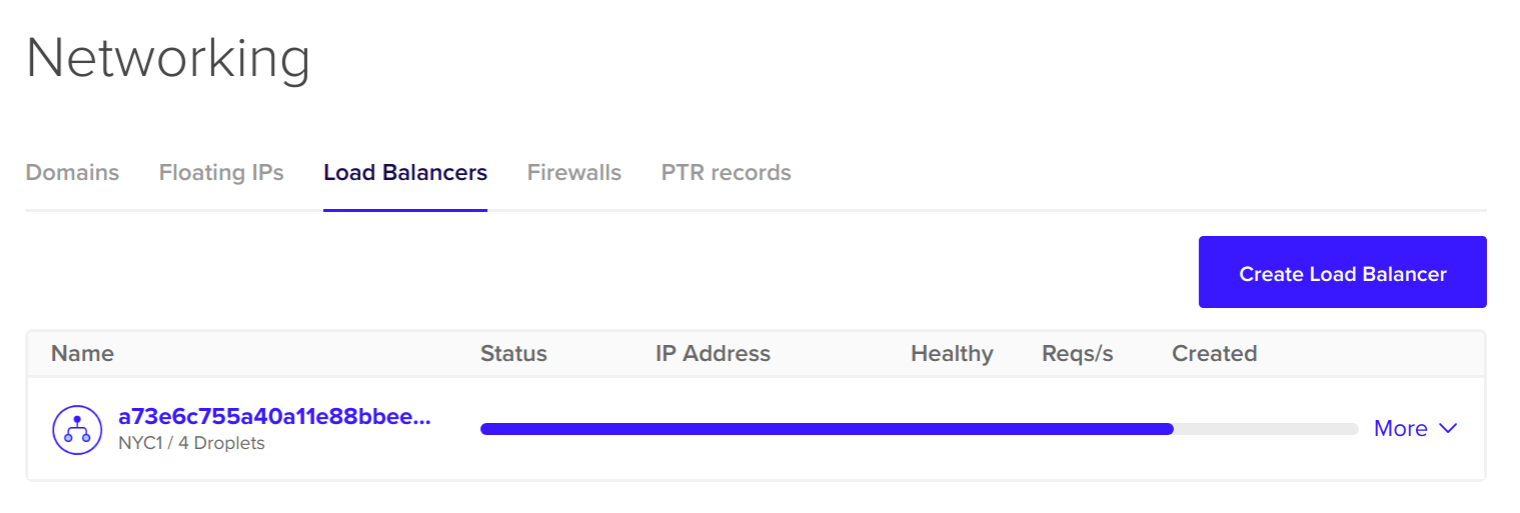

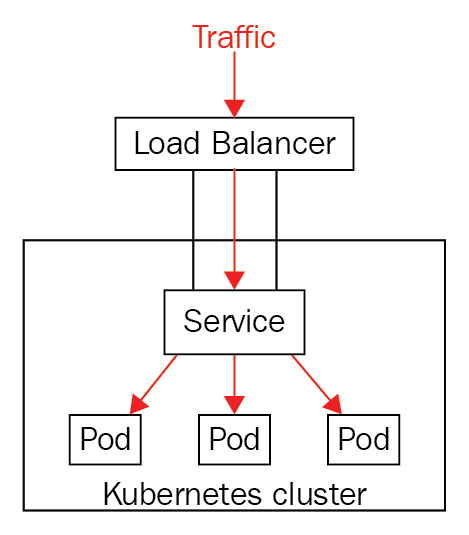

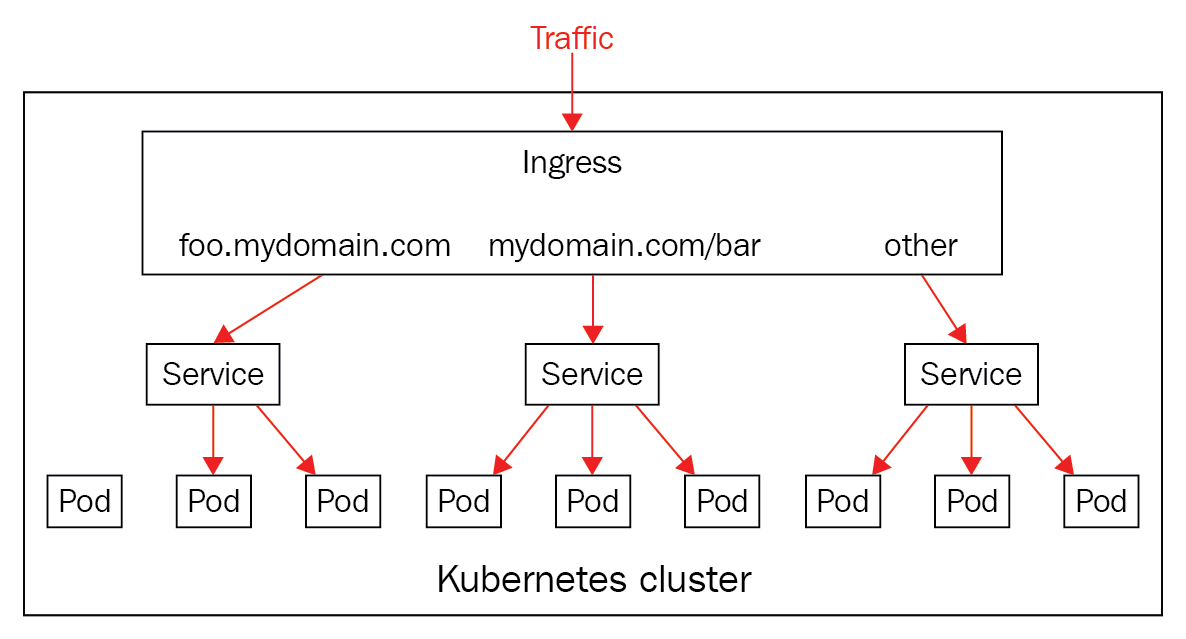

Chapter 18, Robust Infrastructure with Kubernetes, deploys our application into a cluster using Kubernetes, a cluster management tool that combines discovery services, global configuration stores, schedulers, and load balancers. This ensures that our application is highly-available, reliable, scalable, and performant.

Chapter 19, Important Concepts in JavaScript, provides a comprehensive primer on the most fundamental (and most overlooked) principles of JavaScript, including data types, prototypes, the prototype inheritance chain, ES6 classes, this, context, and the execution context.

https://www.packtpub.com/sites/default/files/downloads/ImportantConceptsinJavaScript.pdf

Chapter 20, Writing in ECMAScript 2015+, guides you through the newer features of JavaScript, such as let/const, defaults, destructuring assignment, rest and spread operators, template literals, and promises.

https://www.packtpub.com/sites/default/files/downloads/WritinginECMAScript2015.pdf

As you may appreciate, by covering all these tools in a single book, it's impossible to examine any of them in great detail. Thus, we've selected the most fundamental concepts to cover, leaving the finer details to more advanced books.

There were also topics that we wanted to include but simply did not have the page count to do so. Notably, these important concepts are not covered:

We've structured this book so that each chapter builds on the previous one. As such, this book is meant to be read in a sequential manner.

This book focuses on the tools and frameworks in the JavaScript ecosystem, not on the JavaScript language itself. Therefore, I'd expect readers of this book to have a basic understanding of the JavaScript syntax.

Before we introduce each tool, we'll try to answer the following questions:

You should consider this book as a learning exercise, rather than a reference manual. We want you to understand why a tool is needed, and not just copy-and-paste sample code into your terminal or editor. Ergo, there will be instances where we implement a feature in a sub-optimal way, only to improve it at a later date.

We also expect you to get hands-on and write a lot of the code yourself. In many parts of the book, we will teach you the required concepts, guide you through a few examples, and leave you to implement the rest. We strongly encourage you to use this opportunity to practice what you've learned; however, if you ever get stuck, or are eager to move on to the next chapter, you can always refer to the code bundle that comes with the book.

Due to the fast-changing nature of the ecosystem, many tools will inevitably introduce breaking changes after the publication of this book. As a result, some of the instructions may not work as described. In those cases, you should read the release notes or migration guide published by the tool's author; alternatively, you may search for help on the internet and Q&A sites. On our end, we will try to maintain up-to-date package versions and instructions in our code bundle, which is hosted on GitHub.

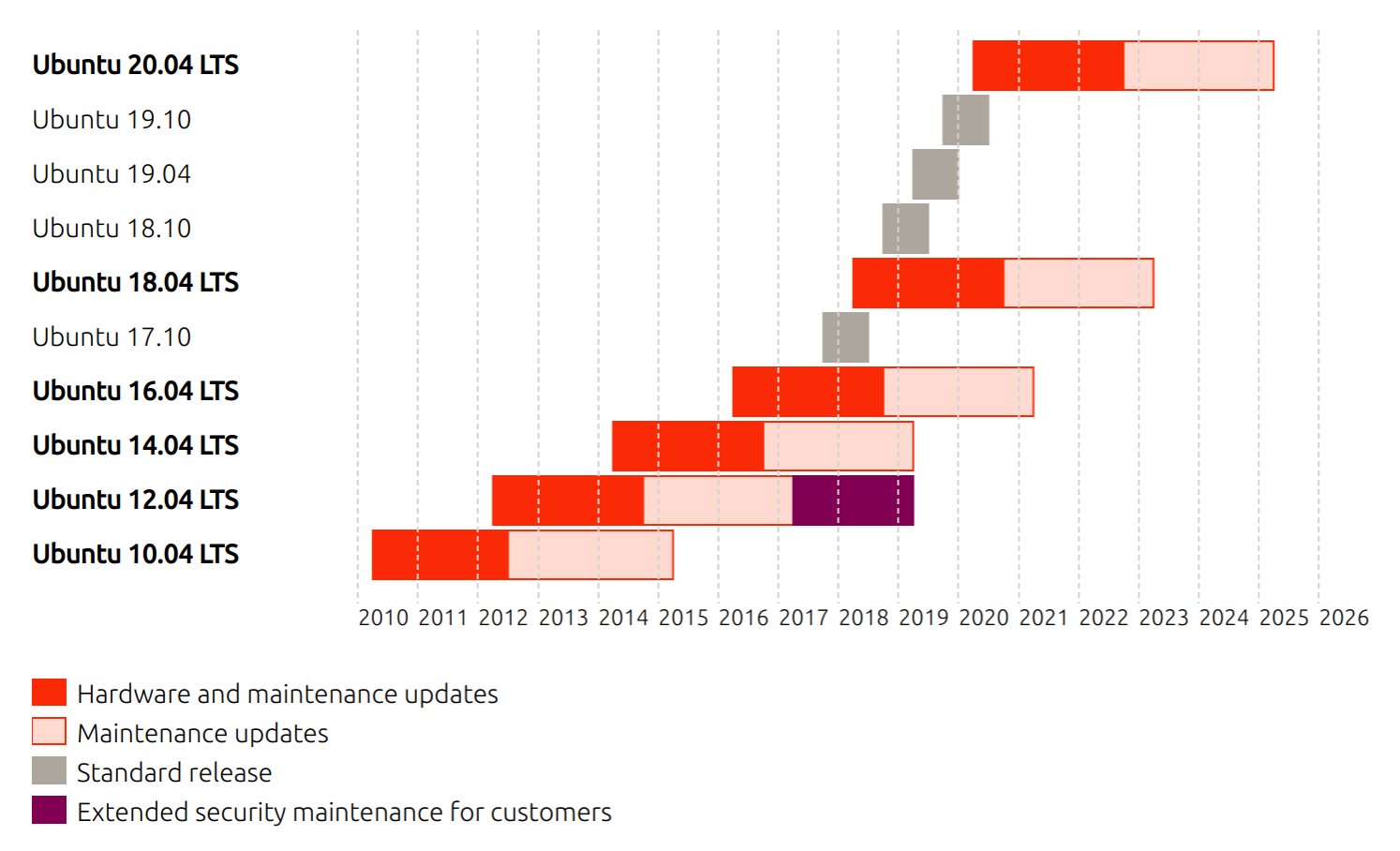

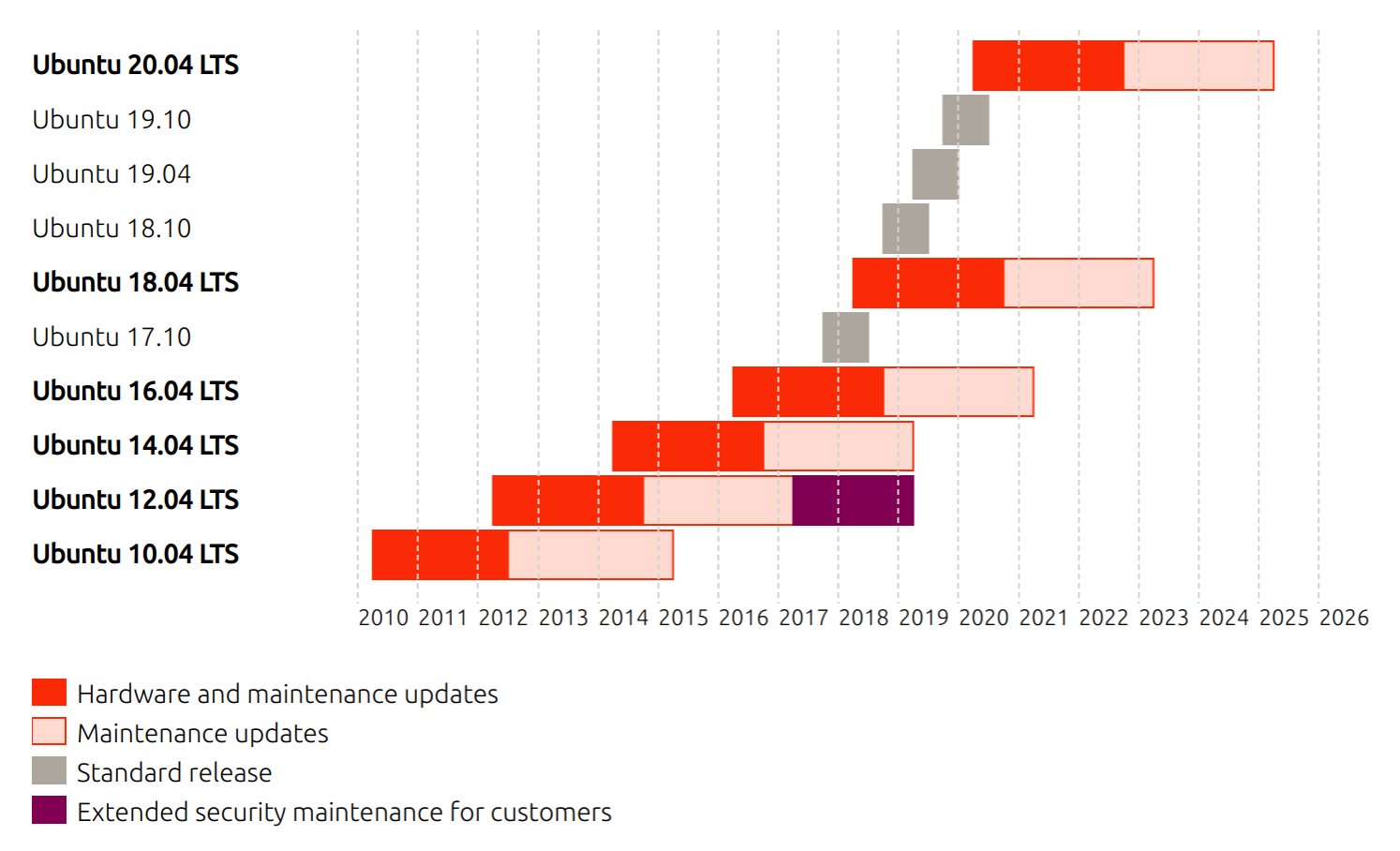

The instructions in this book are intended to run on a machine running GNU/Linux, specifically Ubuntu 18.04. Readers using other operating systems should still be able to follow along but may require more effort in setting up and debugging. Readers using Windows machines should set up their computers to dual boot Ubuntu and Windows; you can find detailed instructions at help.ubuntu.com/community/WindowsDualBoot. Alternatively, if you're using Windows 10, you can install Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL), which allows you to natively run command-line tools and applications you'd normally expect to see in GNU/Linux. You can find detailed instructions at docs.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/wsl/.

Finally, this book is the culmination of a 16-month journey. I have learned a lot along the way, and have also gained a few gray hairs. I hope you enjoy reading this book as much as I've enjoyed writing it!

You can download the example code files for this book from your account at www.packtpub.com. If you purchased this book elsewhere, you can visit www.packtpub.com/support and register to have the files emailed directly to you.

You can download the code files by following these steps:

Once the file is downloaded, please make sure that you unzip or extract the folder using the latest version of:

The code bundle for the book is also hosted on GitHub at https://github.com/PacktPublishing/Building-Enterprise-JavaScript-Applications. In case there's an update to the code, it will be updated on the existing GitHub repository.

We also have other code bundles from our rich catalog of books and videos available at https://github.com/PacktPublishing/. Check them out!

There are a number of text conventions used throughout this book.

CodeInText: Indicates code words in text, database table names, folder names, filenames, file extensions, pathnames, dummy URLs, user input, and Twitter handles. Here is an example: "Mount the downloaded WebStorm-10*.dmg disk image file as another disk in your system."

A block of code is set as follows:

{

"files": ["*.test.js"],

"env": {

"mocha": true

},

"rules": {

"func-names": "off",

"prefer-arrow-callback": "off"

}

}

Any command-line input or output is written as follows:

$ npx mocha

$ npx mocha "src/**/*.test.js"

Bold or Italics: Indicates a new term, an important word, or words that you see onscreen. For example, words in menus or dialog boxes appear in the text like this. Here is an example: "Select System info from the Administration panel."

Feedback from our readers is always welcome.

GGeneral feedback: If you have questions about any aspect of this book, mention the book title in the subject of your message and email us at customercare@packtpub.com.

Errata: Although we have taken every care to ensure the accuracy of our content, mistakes do happen. If you have found a mistake in this book, we would be grateful if you would report this to us. Please visit www.packt.com/submit-errata, selecting your book, clicking on the Errata Submission Form link, and entering the details.

Piracy: If you come across any illegal copies of our works in any form on the Internet, we would be grateful if you would provide us with the location address or website name. Please contact us at copyright@packtpub.com with a link to the material.

If you are interested in becoming an author: If there is a topic that you have expertise in and you are interested in either writing or contributing to a book, please visit authors.packtpub.com.

Please leave a review. Once you have read and used this book, why not leave a review on the site that you purchased it from? Potential readers can then see and use your unbiased opinion to make purchase decisions, we at Packt can understand what you think about our products, and our authors can see your feedback on their book. Thank you!

For more information about Packt, please visit packt.com.

One thing that separates a good company from a great company is their processes. In a great company, everyone understands what is expected of them, what they can expect from others, the vision of the company, and the philosophy of the workplace. With that foundation, the staff has the freedom to be creative and innovate, working within the processes and boundaries set by the company.

When there are no processes, there is chaos. Developers wouldn't know what to expect— are the requirements and specifications documented? Where can I find them? They also wouldn't understand what's expected of them—do I need to write tests or is this a Proof of Concept (PoC)? What edge cases should I test for? Without processes, managers and developers will waste time chasing requirements and clarifications, giving them less time to be creative and innovative, and thus excel at their jobs.

Ultimately, a chaotic environment leads to a product that's lower in quality. On the technical side, there'll be more technical debt—bugs and inefficiencies that need to be fixed later. The product team will suffer too, as fewer features would be delivered.

For these companies, the best way to improve is simply to start implementing robust processes on the technical level by implementing Test-Driven Development (TDD), and on the management level by adopting Agile principles and/or implementing the Scrum framework. In this chapter, we will focus on the technical aspect—implementing TDD. Specifically, we will cover the following:

One of the most popular questions on the Software Engineering Stack Exchange (https://softwareengineering.stackexchange.com/) website is this:

Whilst this should never be regarded as normal, for many developers, it is their reality. So, why do so many projects end up in an unmaintainable state? After all, every project starts off with a blank slate.

Some may say that it's because most programmers are inherently lazy, but most also take pride in their work, and value quality over speed. Others may say it's because the developers are incompetent, but even companies that employ very talented technical teams fall victim to this.

My theory is that during the lengthy development process, it's too easy to make little concessions along the way, where code quality is sacrificed to save other resources, usually time. For instance, you may stop writing tests to meet a deadline, or forgo refactoring because your manager assures you that the project is just a PoC or Minimum Viable Product (MVP). Little by little, these small concessions build up. Oftentimes, the deadlines become ever more unreasonable, and the MVP becomes the company's flagship product. That's how we end up with so many unmaintainable projects in this world.

These compromises, although small at the time, have a knock-on effect on the code that is written afterward. This cumulative effect is described using the metaphor of technical debt, which plays on the analogy of financial debt, where you incur compound interest on your existing debts.

Technical debt is a metaphor created by Ward Cunningham, an American computer programmer:

For example, if you want to start your own business, but do not have enough personal savings, you may opt to take out a loan with a bank. In this case, you incur a small debt now in order to acquire a potentially larger reward later, when your business generates a profit.

Likewise, you may decide to incur some technical debt in order to capture the First-Mover Advantage (FMA) to ship a feature before your competitors go to market. The debt comes in the form of poorly-written code; for instance, you may write everything into a single file (colloquially called a kitchen sink) with no modularization or tests.

In both cases, the debt is incurred with the expectation that it will be repaid, with interest, at a later date.

For development, repayment comes in the form of refactoring. This is where time is re-invested to revise the poorly-written code back to an acceptable standard. As this requires time and manpower, by incurring the technical debt, you are, in essence, trading a moderate increase in development speed now for a significant decrease later.

The problem arises when the debt is not repaid sufficiently quickly. At some point, the amount of maintenance done on the project is so great that no more features can be added, and the business may opt for a complete rewrite instead.

Before we discuss how to tackle technical debt, let's first examine some of its most common causes:

All of these causes can easily be mitigated. The problem of inexperienced developers can be tackled through mentoring, code reviews, and general training. The problem of morale can be tempered by providing better working environments. The issue of lack of time can be remedied by reducing the scope of the project to something more achievable; this may mean pushing non-essential features to a subsequent phase. Besides this, the business can employ more staff and/or outsource the development of well-defined modules to external contractors.

The real problem lies in the reluctance to tackle technical debt, since the biggest cause of technical debt is the existing technical debt. Any new code that depends on the bad code will very soon become part of the technical debt and incur further debt down the line.

When you talk with product managers or business owners, most of them understand the concept of technical debt; however, most managers or business owners I've encountered also tend to overestimate the short-term returns and underestimate the long-term consequences. They believe that technical debt works like personal loans issued by banks, with an interest rate of around 3% Annual Percentage Rate (APR); in reality, it works more like payday loans that charge you 1500% APR.

In fact, the debt metaphor isn't completely accurate. This is because, unlike a formalized loan, when you incur technical debt, you don't actually know the interest rate or repayment period beforehand.

The debt may require one week of refactoring time that you can delay indefinitely, or it may cost you a few months' time just a few days down the line. It is very hard to predict and quantify the effect of technical debt.

Furthermore, there's no guarantee that by incurring the debt, the current set of features are actually going to be finished earlier. Often, the consequences of technical debt are close to immediate; therefore, by rushing, it may actually slow you down within the same development cycle. It is very hard to predict and quantify the short-term benefits of incurring technical debt. In that sense, incurring technical debt resembles more of a gamble than a loan.

Next, let's examine the consequences of technical debt. Some are obvious:

On the other hand, the human cost of technical debt is often overlooked; so let's spend some time discussing it here.

Most developers want to work on greenfield projects where they can develop new features, rather than to inherit legacy brownfield projects riddled with bugs and technical debt. This will likely reduce the morale of the developers.

In some cases, those working on brownfield projects may even show animosity toward their colleagues who work on greenfield projects. This is because newer frameworks, libraries, and paradigms will eventually replace older ones, making them obsolete. Those working on legacy projects know that the skills they develop will be worthless in a few years' time, making them less competitive on the job market. In comparison, their colleagues are gaining valuable experience on more modern frameworks that will increase their market value. I can't imagine a developer being happy knowing their skills are becoming less and less relevant.

Furthermore, having technical debt would likely ignite disagreement between developers and their managers about the best time to repay the debt. Typically, developers demand immediate repayment, while the (inexperienced) managers would try to push it further down the line.

Overall, having technical debt in the project tends to lower the morale of its developers.

In turn, low morale leads to the following:

Some managers may argue that the business is not responsible for the happiness of its developers—they pay them to produce work and value, not to be happy. Whilst this is true, an experienced project manager should remember that a development team is not a machine—it consists of people, each with their individual ambitions and emotions. Thus, the manager would be wise to consider the human costs of technical debt when making a business decision.

Despite its negative repercussions, incurring technical debt is often inevitable. In those cases, you must ensure that the decision is an informed and conscious one, and remember to repay the debt as soon as possible. So how do we actually pay back the debt? We do this through refactoring—or making our code cleaner without changing the existing behavior.

Whilst there are no formal definitions on what clean means, here are some signs of clean code:

As you gain more experience, you'll be able to detect code that deviates from these signs. In programming, we call these deviations code smells. Code smells are weaknesses within the code that violate well-established design principles, paradigms, and patterns. While they are not bugs themselves, they may slow down development and make the code base more prone to errors later.

Therefore, refactoring is simply a process that moves the current code base from having a lot of code smells to one that is cleaner. As we have mentioned before, there is more than one way to achieve the same results, and developers need to be creative and figure out the best solutions to problems that arise.

The important point here is that developers should be given time to refactor; in other words, refactoring should be the core part of a development process, and be included in the time estimates that the developers provide.

Prevention is better than cure. Instead of incurring technical debt, how about avoiding it in the first place? Here, we outline some easy tactics that you can adopt to prevent technical debt.

Most decision makers, especially those without a technical background, greatly underestimate the effects of technical debt. Furthermore, in their view, developers do not understand the business costs of repaying technical debt in terms of manpower, salaries, and time.

That's why it is important for a professional developer to understand the situation from the decision maker's perspective and the constraints that they must work within. One of the most relevant models is the triple constraint model.

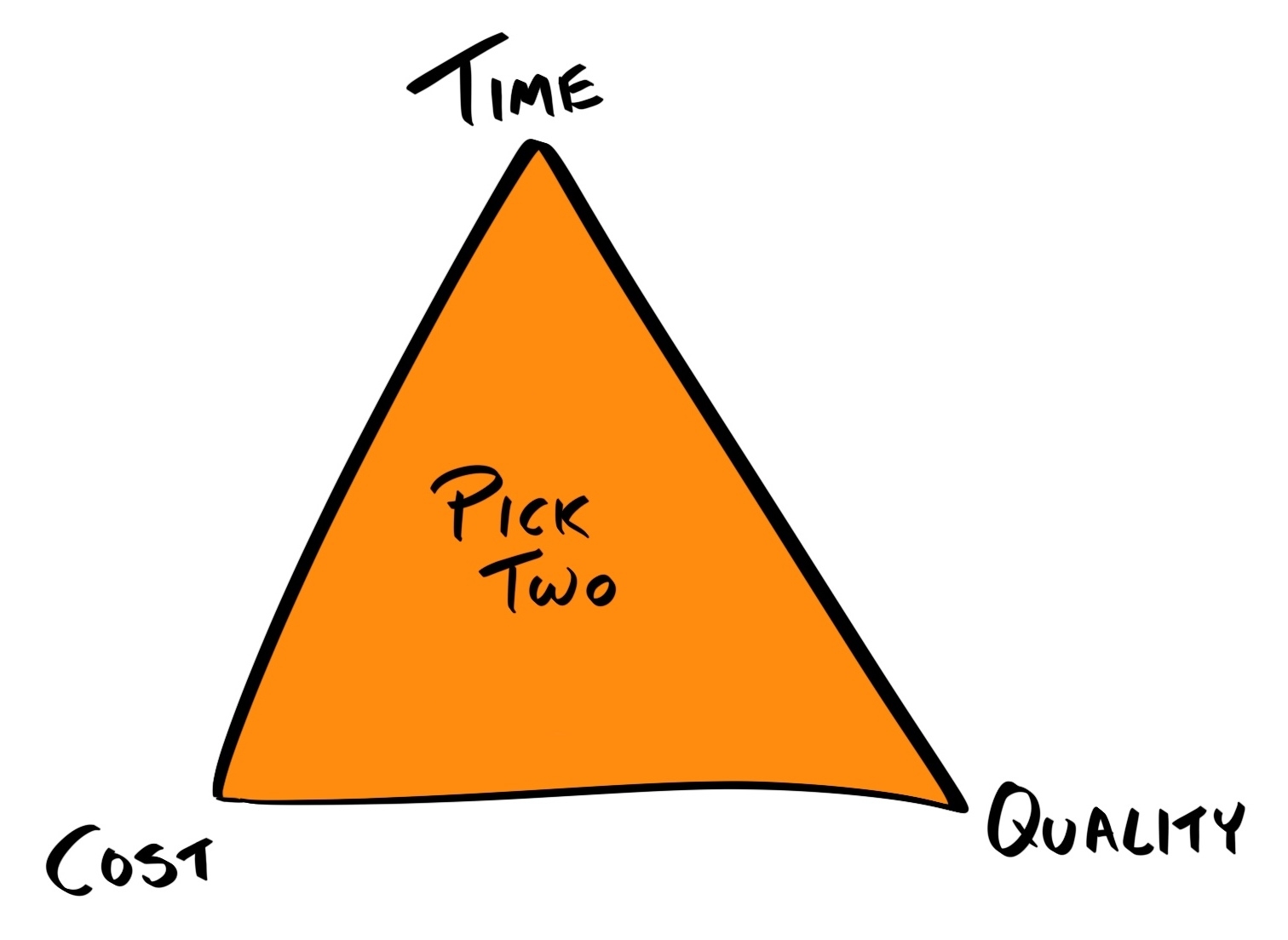

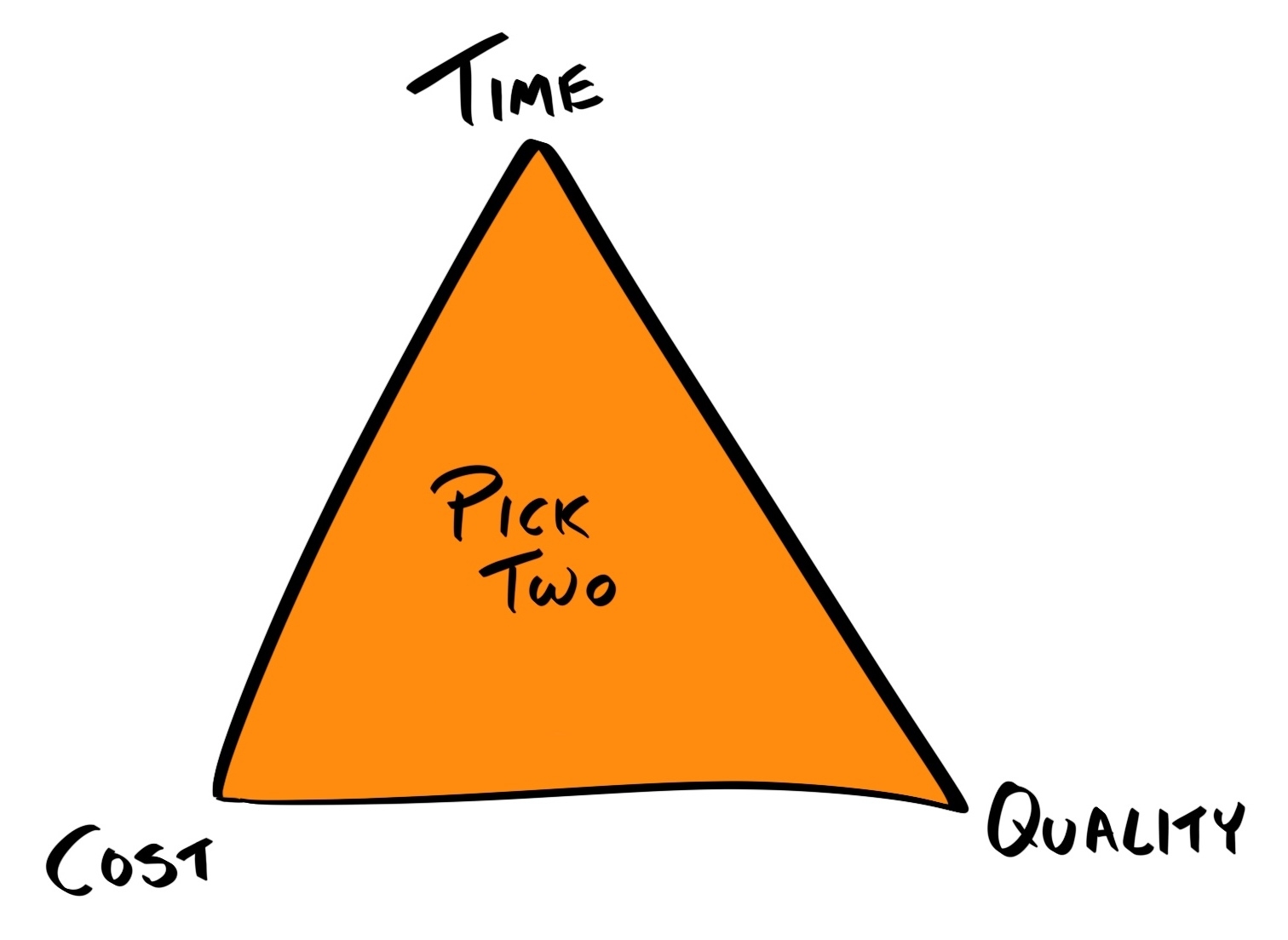

The classic project management triangle (also known as triple constraint or the iron triangle) coined the popular saying Time, Quality, Cost. Pick two. The triangle is shown as follows:

The triple constraint is a model used in project management to visualize the constraints on any projects, and to consider how optimizing the project for one area would cause another area to suffer:

Most businesses are limited largely by their time and cost: by time, because for each day the product is not launched, the greater the chance their competitor delivers a similar product and captures the first-mover advantage (FMA); by cost, because the company still has to pay their staff salaries while the product is not generating any revenue.

To exacerbate the problem, many managers and business owners are focused more on tangible, immediate results, rather than long-term rewards. For these reasons, when given the choice, most decision-makers pick time and cost over quality.

The fallacy here is that by neglecting quality and incurring debt, they'll eventually be increasing both the time and cost requirements many times over.

Therefore, it is the duty of the developer to inform the product manager and business owner of the unpredictable effects of incurring technical debt to give them all of the advice they need to make an informed decision. You may want to turn the tables and approach it from a positive perspective—cleaning up technical debt would allow future development of new features to be completed more quickly.

Do this to prevent the worst-case scenario where the effort required to fix the code is greater than rewriting everything from scratch.

If the code base is so bad that it's close to FUBAR (a variation on the military slang that stands for 'Fucked Up Beyond Any Repair'), then a more drastic approach may be to refuse further development until refactoring is done. This may seem extreme, given that the people you're disobeying are paying your salary. While this is an easy way to forgo responsibility, it's not what a professional developer should do.

To paraphrase an analogy from The Clean Code by Robert C. Martin: Let's suppose you are a doctor and a patient asks you to perform open heart surgery on him/her in order to relieve a sore throat, what would you do? Of course, you'd refuse! Patients do not know what are best for them, that's why they must rely on your professional opinion.

Likewise, most business owners do not know what is best for them technically, which is why they hired you to make the best possible technical decisions for their business. They pay you not simply to code; they pay you because they want you to bring value to the business. As a professional, you should think about whether your actions are beneficial or detrimental to the business, in both the short and long term.

Business owners also need to trust the advice of their developers. If they do not respect their professional opinion, they shouldn't hire them in the first place.

However, it's not always the business owner's fault for making unreasonable demands; the developer who commits to those demands is equally at fault.

Remember, it is the business owner's, or your manager's, role to get as much out of you as possible. But more importantly, it is your duty to inform them of what is and isn't possible; so, when asked to complete features under a deadline that you cannot meet without sacrificing on quality, do not accept the deadline.

You may think the business would appreciate you for going the extra mile and making the impossible possible, but there are four problems with this line of thinking:

There's a time to stick your head out to save a business, but by doing it too often, you are actually hurting the team. The danger is that neither you nor the business owner will realize this; in fact, you may even naïvely celebrate the rapid progress being made.

The solution here is to manage your business owner's expectations. If you believe there's a 50% chance of meeting an optimistic deadline, then ask for the scope to be reduced further until you can be more confident in your estimate. Speaking from experience, business owners would rather hear it's not possible a month in advance than a promise of everything will be done that was not delivered.

This brings me back to the topic of defining and documenting processes. Good code starts with good planning, design, and management, and is maintained by good processes. Many of the problems outlined previously can be mitigated if there are clear guidelines outlining the following issues:

Software development paradigms such as Agile and Waterfall, as well as their implementations such as Scrum and Kanban, provide different ways to define and enforce these processes. For example, in Scrum, development happens in short iterations (typically one and four weeks) called sprints. At the beginning of each sprint, a meeting is held to review pending tasks and select features to be tackled in this sprint. At the end of each sprint, a retrospective meeting is held to review the progress of the sprint and identify lessons that can be learned and applied to subsequent sprints.

Although these paradigms and methodologies are popular in software development, they are not coupled to any technical processes at all. Instead, they deal with the entire development process, including gathering requirements and specifications, communicating with the client, design, development, and deployment.

Therefore, of more relevance to developers are development techniques, which specify how a developer should develop a feature. The most prominent technique is TDD.

Test-Driven Development is a development practice created by Kent Beck, it requires the developer to write tests for a feature before that feature is implemented. This provides some immediate benefits:

So, let's examine the principles of TDD, outline its process, and see how we can incorporate it into our workflow.

TDD consists of a rapid repetition of the following steps:

For example, if we want to build a math utility library, then our first iteration of the TDD cycle may look like this:

var assert = require('assert');

var sum = require('sum');

describe('sum', function() {

it('should return 34 when 15 and 19 are passed in', function() {

assert.equal(34, sum(15, 19));

});

});

const sum = function(x, y) {

return x + y;

}

This completes one cycle of the TDD process. In the next cycle, we will work on the same function, but define additional test cases:

describe('sum', function() {

...

it('should return 105 when 56, 32 and 17 are passed in', function() {

assert.equal(105, sum(56, 32, 17));

});

});

const sum = function(x, y, z) {

return x + y + z;

}

const sum = function(...args) => [...args].reduce((x, y) => x + y, 0);

Note that calling with just two arguments would still work, and so the original behavior is not altered.

Once a sufficient number of test cases have been completed, we can then move on to the next function, such as multiply.

By following TDD, the number of bugs should reduce drastically; however, no process can guarantee error-free code. There will always be edge cases that were overlooked. Previously, we outlined the TDD process for implementing a new feature; now, let's look at how can we can apply the same process to fixing bugs.

In TDD, when a bug is encountered, it is treated the same way as a new feature—you'd first write a (failing) test to reproduce the bug, and then update the code until the test passes. Having the bug documented as a test case ensures the bug stays fixed in the future, preventing regression.

When you first learn to code, no one ever starts with writing tests. This means that for many developers, having tests in the code is an afterthought—a luxury if time permits. But what they don't realize is that everyone tests their code, consciously or otherwise.

After you've written a function, how do you know it works? You may open the browser console and run the function with some dummy test parameters, and if the output matches your expectations, then you may assume it's working. But what you're doing here is actually manually testing a function that has already been implemented.

The advantage of manual testing is that it requires no upfront costs—you just run the function and see if it works. However, the downside is that it cannot be automated, eating up more time in the long run.

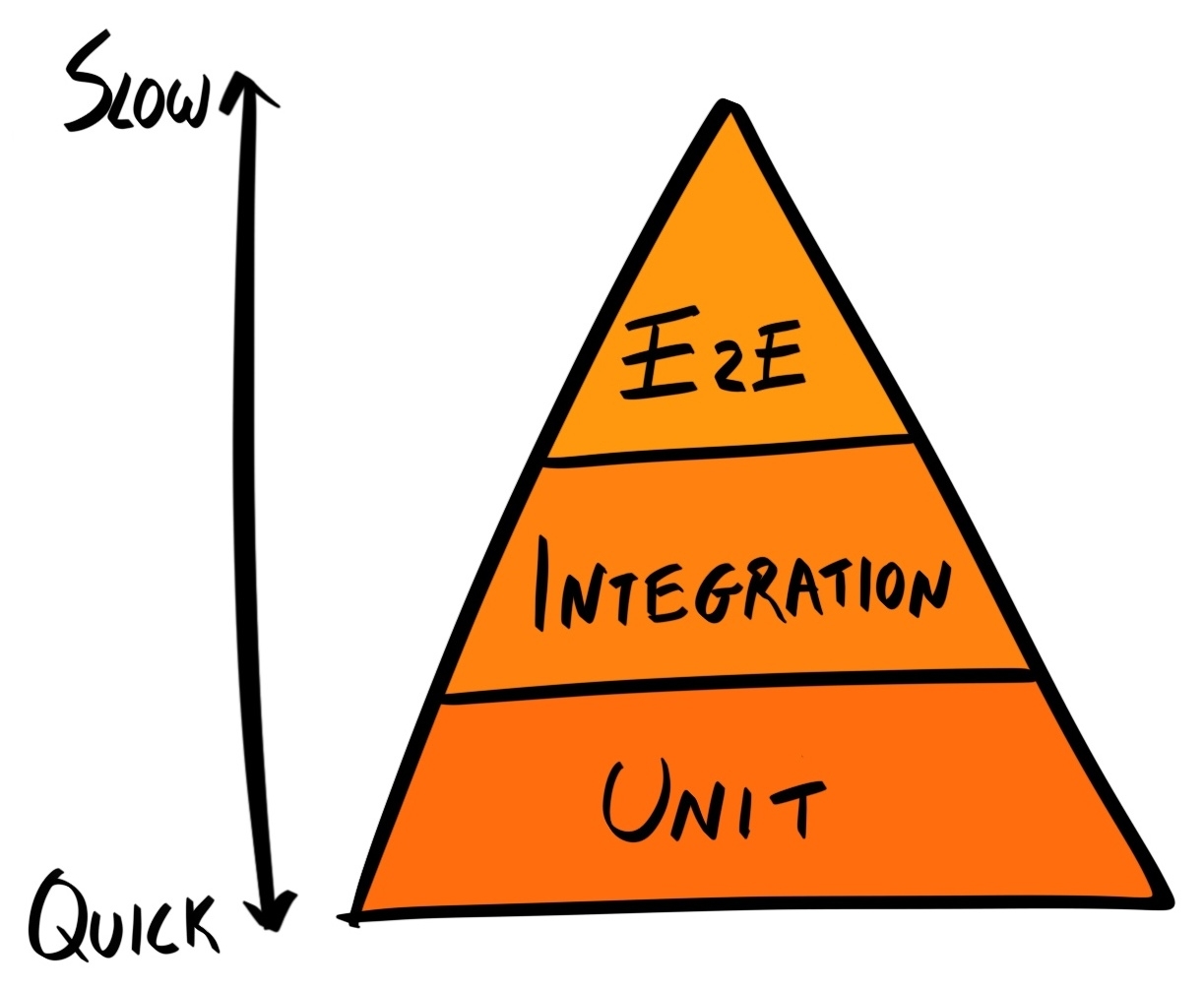

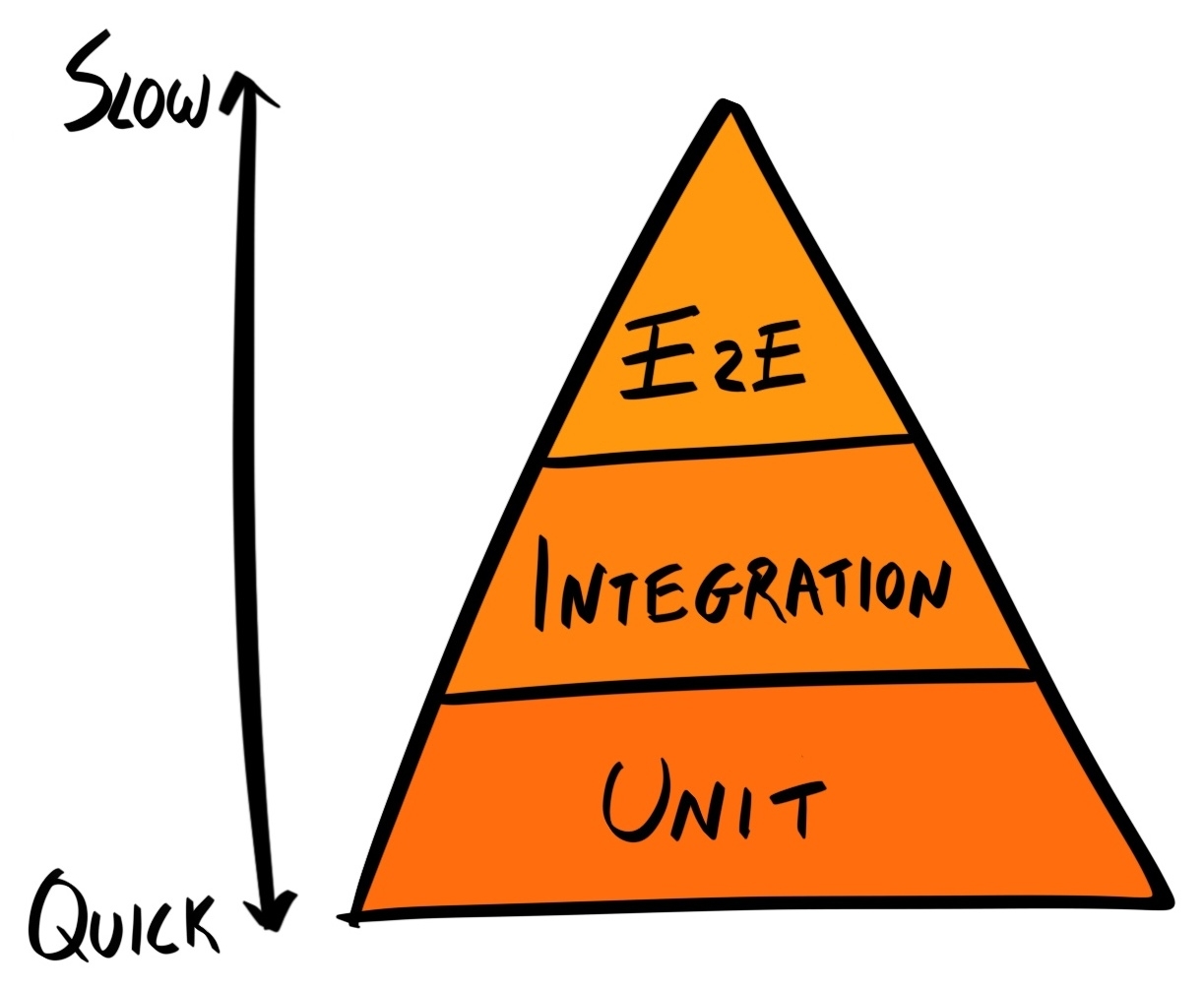

Instead, you should formally define these manual tests as code, in the form of unit, integration and end-to-end (E2E) tests, among others.

Formally defining tests has a higher initial cost, but the benefit is that the tests can now be automated. As we will cover in Chapter 5, Writing End-to-End Tests, once a test is defined as code, we can use npm scripts to run it automatically every time the code changes, making the cost to run the tests in the future virtually zero.

The truth is that you'll need to test your code anyways; it's just a choice of whether you invest time to automate it now, saving time in the future, or save the time now but waste more time repeating each test manually in the future.

Mike Cohn developed the concept of the Testing Pyramid, which shows that an application should have a lot of unit tests (as they are fast and cheap to run), fewer integration tests, and even fewer UI tests, which take the most amount of time and are the most expensive to define and run. Needless to say, manual testing should only be done after unit, integration, and UI tests have been thoroughly defined:

Whilst avoiding manual testing is a benefit of TDD, it certainly is not the only one. A developer can still write their unit, integration and E2E tests after implementation of the feature. So what are the benefits of writing tests before implementation?

The answer is that it forces you to think about your requirements and break them down into atomic units. You can then write each test case around a specific requirement. The end result is that the test cases form the specification for your feature. Writing tests first helps you structure your code around the requirements, rather than retrofitting requirements around your code.

This also helps you to abide by the You Aren't Gonna Need It (YAGNI) principle, which prevents you from implementing features that aren't actually needed.

Lastly, writing the tests (and thus the specifications) forces you to think about the interface that consumers of your function would have to use to interact with your function—should everything be defined as properties inside a generic options object, or should it be a plain list of arguments?

// Using a generic options object

User.search(options) {

return db.users.find(options.name, {

limit: options.limit,

skip: options.skip

})

}

// A list of arguments

User.search(name, limit, skip) {

return db.users.find(name, {limit, skip});

}

When developers want to use a tool or library, they learn by reading the documentation or guides that contain code samples they can try, or by following tutorials to build a basic application.

Test cases can essentially act as code samples and form part of the documentation. In fact, tests are the most comprehensive set of code samples there are, covering every use case that the application cares about.

Because TDD focuses on a single functional block at a time, its development cycles are usually very short (minutes to hours). This means small, incremental changes can be made and released rapidly.

When TDD is implemented within the framework of a software development methodology such as Scrum, small development cycles allow the methodology practitioner to capture fine-grained metrics on the progress of the team.

While TDD is the gold standard amongst development techniques, there are many obstacles preventing its implementation:

Although I encourage you to incorporate TDD into your workflow, I should add a disclaimer that it is not a silver bullet. TDD does not magically make your code performant or modular; it's just one technique that forces you to design your system better, making it more testable and maintainable.

Furthermore, TDD induces a high initial cost, so there are a few cases where this investment is not advisable:

In this chapter, we've looked at technical debt, its causes, consequences, and ways to prevent it. Then, we introduced TDD as a process to avoid technical debt; we outlined its benefits, and how to implement it in your workflow. In Chapter 5, Writing End-to-End Tests and Chapter 6, Storing Data in Elasticsearch, we will cover in more depth the different types of tests (unit, integration, and E2E / acceptance tests).

Good code, whatever its definition, takes less time to write than bad code in the long run. It would be wise to realize this fact and have the discipline to build a strong foundation from the get-go. You can build a house on weak foundations, and it may stand for a hundred years, but build a skyscraper on a weak foundation, it'll come tumbling down quicker than you can imagine.

avaScript has not traditionally been considered a backend language; that space belonged to the likes of Java, Python, C/C++, C#/.NET, PHP, Ruby and so on. JavaScript was just a 'toy language' that allowed web developers to add animation to websites in order to improve its aesthetics. But this all changed with the advent of Node.js. With Node.js, developers can now write JavaScript code that executes on the server, as well as the client. In other words, developers can now write both front and backend code using the same language!

This provides huge productivity benefits, as common code can now be shared across the stack. Furthermore, developers can avoid context switching between different languages, which often breaks concentration and reduces output.

It also led to the rise in Isomorphic, or Universal, JavaScript frameworks, such as Meteor. These types of frameworks allow you to write applications entirely in JavaScript that run on both the client and the server.

Here's what we'll cover in this chapter:

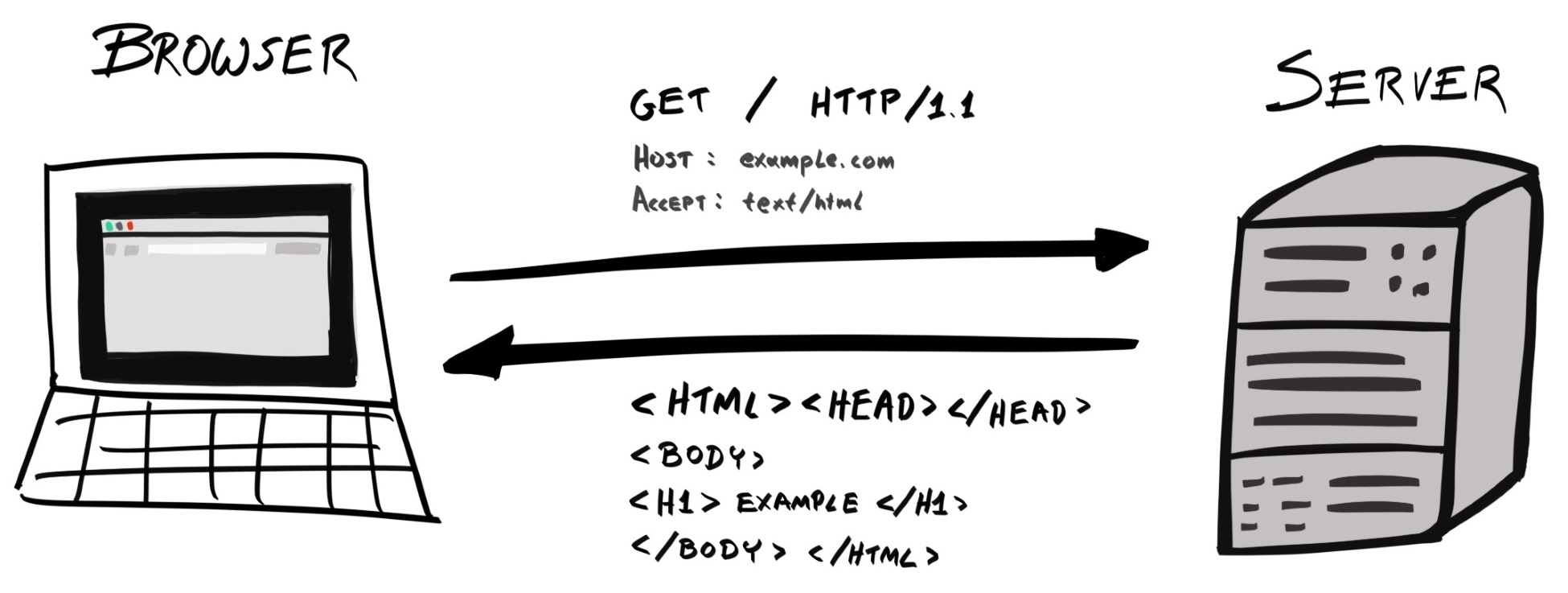

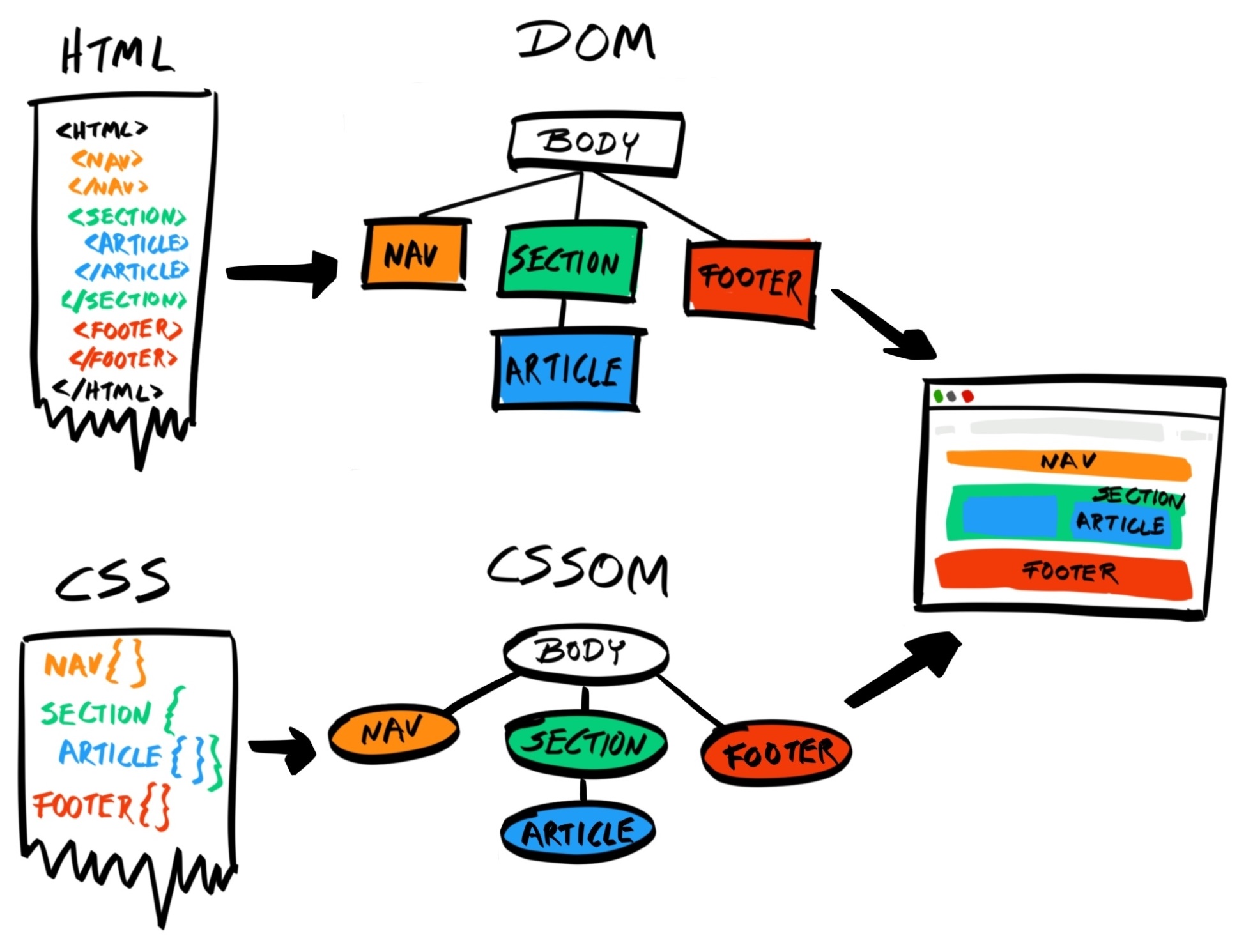

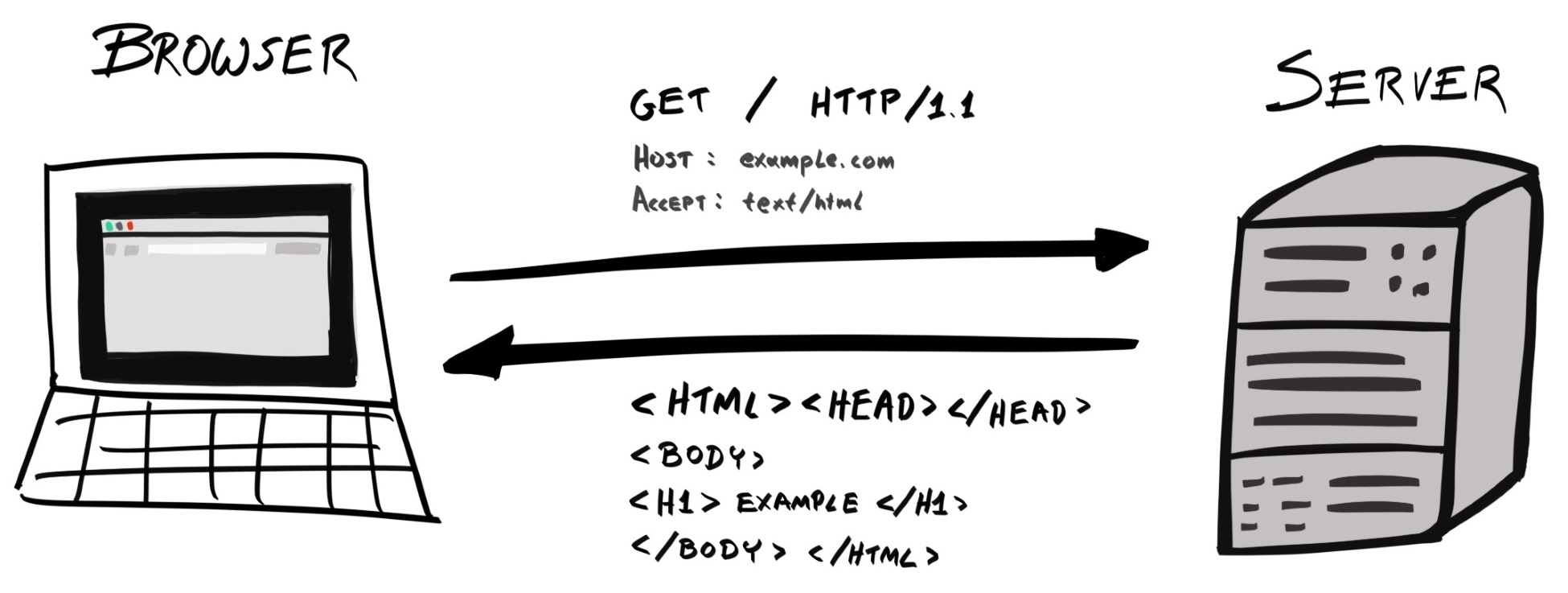

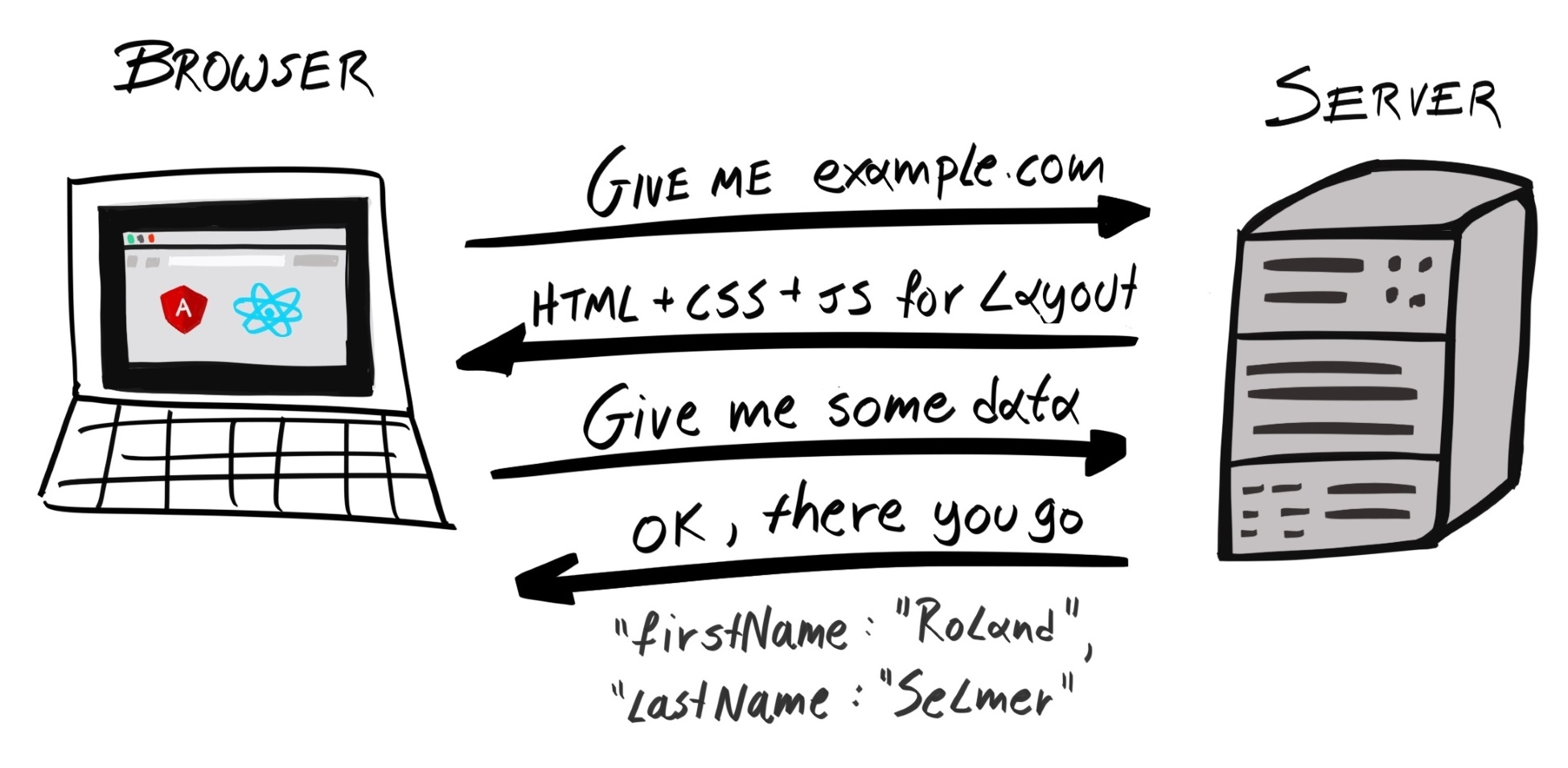

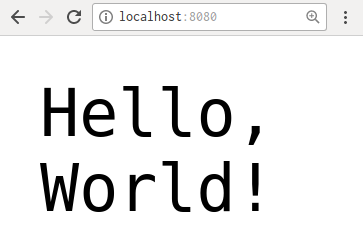

When you type a URL, such as www.example.com, into your browser, what actually happens? First, the browser would send a request to one of Example Corp's servers, which retrieves the resource requested (for example, an HTML file), and sends it back to the client:

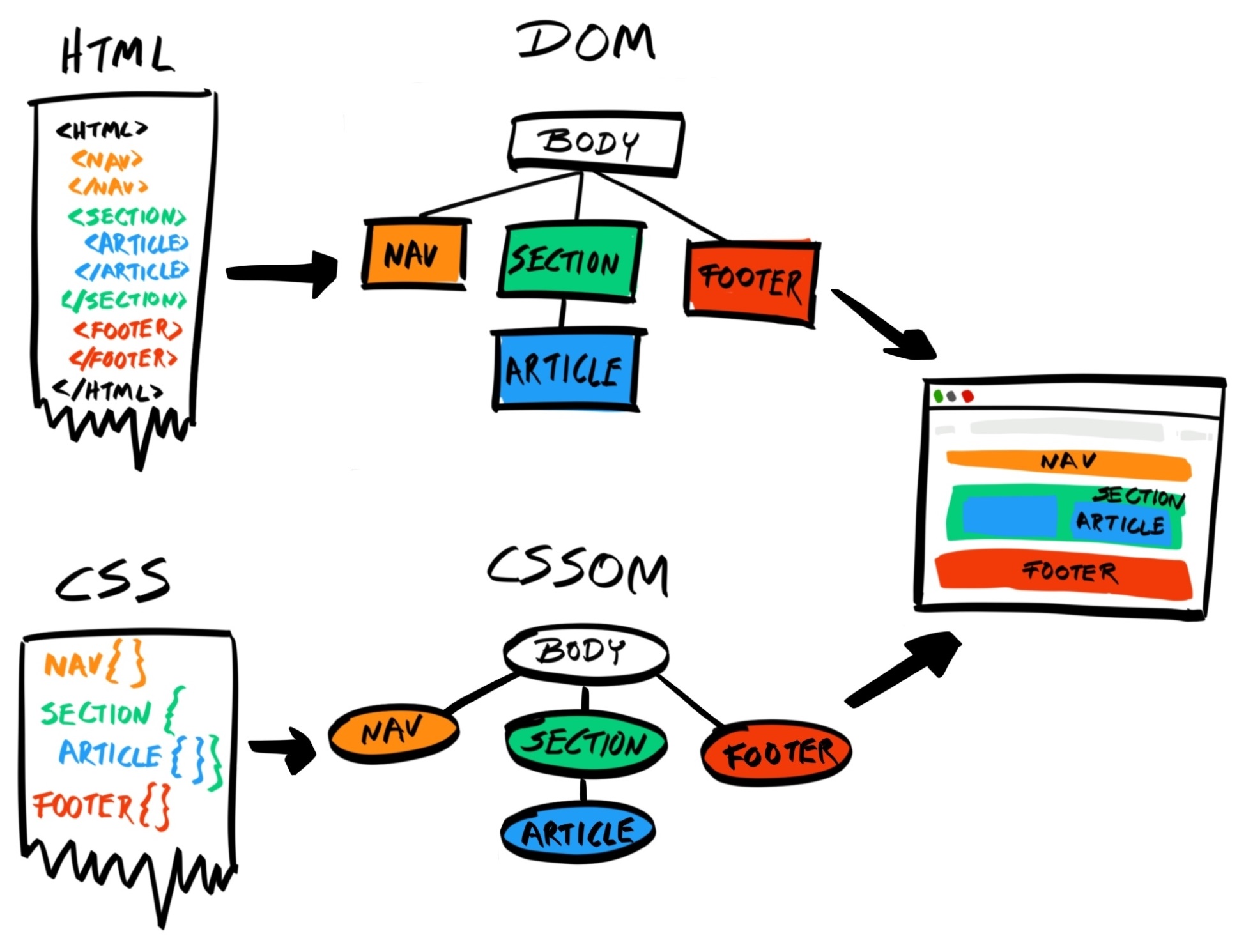

The browser then parses the HTML, retrieves all the files the web page depends on, such as CSS, JavaScript, and media files, and renders it onto the page.

This scheme is known as the client-server model. In this model, most of the processing is handled server-side; the client's role is limited to simple and superficial uses, such as rendering the page, animating menus and image carousels, and providing event-based interactivity.

This model was popular in the 1990s and 2000s, when web browsers were not very powerful. Creating entire applications with JavaScript on the client side was unheard of, and those that had that requirement resorted to Java applets and Adobe Flash (and, to a certain extent, Microsoft Silverlight). However, over time, the computing power of personal devices, such as desktop computers, laptops, and smartphones increased dramatically, and this allowed browsers to handle more elaborate operations.

Between 2008 and 2009, Mozilla, the company behind Firefox, slowly introduced TraceMonkey, the first Just-in-time (JIT) compiler for JavaScript, in different versions of Firefox 3.x, starting with 3.1. Similarly, the V8 JavaScript Engine, which powers Chrome and Safari, and Chakra, which powers Internet Explorer and Edge, also included a JIT compiler.

Traditionally, the JavaScript engine uses an interpreter, which translates the JavaScript source code into machine code that your computer can run. The JIT compiler improved the performance of the engine by identifying blocks of code that are frequently run, compiling them, and adding them to a cache. When the same block of code needs to be run again at a later time, the JavaScript engine can simply run the cached, pre-compiled machine code, skipping the interpreter altogether. Needless to say, this is much faster and the JavaScript engine can execute more operations per unit time, greatly increasing performance.

Because of this increased performance, developers can now build feature-rich JavaScript applications that run on the browser. Google was the first major company to take advantage of this, when they released the first client-side web application framework—Angular - on 20 October 2010. Since then, many competitors have emerged, including Ember, React, and Vue.js, but Angular still remains relevant today.

Angular is a framework for building SPAs. Instead of delegating the bulk of the processing to the server, the client takes on most of the responsibility.

Let's take an e-commerce web application as an example. In the client-server model, when the server receives a request from the client, it will compose a fully-formed HTML and attach it as the payload of the response. If it needs data from the database, it will query the database and inject the data into an HTML template to produce the fully-formed HTML. The client, usually a browser, is then entrusted with the simple task of rendering the HTML onto the screen.

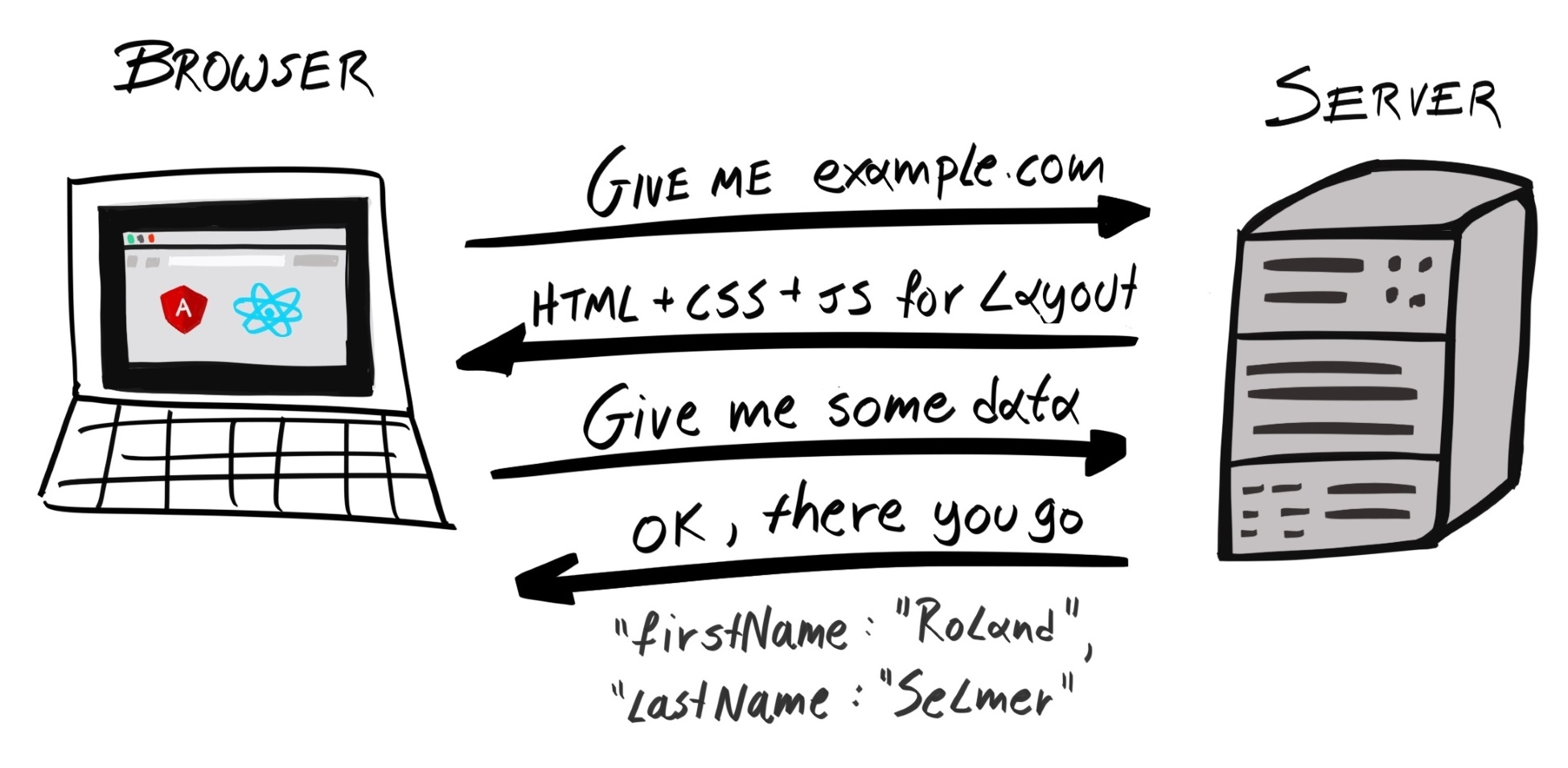

In the SPA model, the server would initially send the entire application, including any HTML, CSS, and JavaScript files, to the client. All the application logic, including routing, now resides on the client. Because of this, the client can update the UI of the application very quickly, as it does not need to wait for a response from the server. Whenever the client requires information it does not have, such as certain entries in the database, it will send a request to the server. The server would then respond with the raw data, usually presented in JSON format, and nothing else. It is then the client's job to process this information and update the UI appropriately. With SPAs, most of the logic is handled client-side; the server's job is simply to retrieve and send back data:

The SPA model has many benefits over the client-server model:

Nowadays, most web applications are built with an SPA framework. Tesla, Sony, Microsoft Support, Genius, Renault, Staples, Udemy, and Healthcare.gov are all websites built with Angular; Airbnb, Asana, BBC, Dropbox, Facebook, Lyft, Netflix, PayPal, and Uber all use React on their websites; although Vue.js is relatively new, several major Asian companies have already adopted it, such as Alibaba, Baidu, Tencent, Xiaomi, and Line.

However, everything has its drawbacks, and SPAs are no exception. The most obvious shortcoming of SPAs is that more code needs to be transferred at the beginning, which can increase the initial load time of the page. To counteract this deficiency, a technique called server-side rendering (SSR) can be employed.

With SSR, the initial page is processed and rendered on the server in the same way as the traditional client-server model. However, the returned HTML contains a tag that'll request the rest of the application to be downloaded at a later time, after the initial page has been successfully rendered. This allows us to improve the initial page load speed, whilst keeping all the benefits of the SPA. Furthermore, SSR is also useful for ensuring Search Engine Optimization (SEO) performance, as it helps web crawlers to quickly decipher how a page should look, without having to download all the assets.

SSR can be used alongside other techniques, such as code splitting and tree shaking, to reduce the size of the initial response payload, thus reducing the time-to-first-render (TTFR) and improving the user experience.

This is the state of the web application today. New web standards such as HTTP/2 and WebAssembly (a.k.a. Wasm) may all change how we approach building web applications in the near future. In the fast-moving world of front-end development, this SPA + SSR model may soon be superseded by a new paradigm.

JavaScript is the language of the browser. There's no denying that. Next, let's examine the reasons why a developer should pick Node.js as the back-end language for their application. Although there are many reasons, here we've boiled it down to two factors—context switching and shared code.

Context switching, or task switching, is when a developer is working on multiple projects, or in different languages, at the same time and has to switch between them regularly.

Programming is an activity that requires you to keep many variables in memory at the same time—variable names, interfaces of different modules, application structure and many more. If you switch to a different project, you'll have to dump the context of the current project and load in the context of the new project. The time required for this switch increases with the complexity of the project, and varies from one individual to the next, but can take anything from a few minutes to a few hours. This makes development extremely inefficient.

This is why, instead of multitasking, you should complete one project before moving on to another.

The same principle applies when switching between different programming languages. When switching between projects, you need to juggle between different contexts; when switching between languages, you need to juggle between different syntax, data structures, and ecosystems. To demonstrate, the following table illustrates some key differences between Python and JavaScript:

| Python | JavaScript |

| Has many data types, including None, Boolean, int, float, complex, list, tuple, range, str, bytes, bytearray, memoryview, set, frozenset, dict, and many more | Has seven data types: undefined, null, Boolean, number, string, symbol, and object |

| Statements are grouped by indentation | Statements are grouped by blocks, expressed using enclosing braces ({}) |

| Uses virtualenv to create isolated environments | Uses Node Version Manager (https://github.com/creationix/nvm) (nvm), package.json, and the local node_modules directory to create isolated environments |

| Uses a class-based inheritance model | Uses a prototype-based inheritance model |

In addition to syntactical differences, different languages may also follow different paradigms—Elixir is a functional language, whereas Java is an object-oriented (OO) language.

Therefore, context-switching between different languages also makes the development process very inefficient.

From a business point of view, using different languages for the front- and back-end means they need to hire two different types of developer: JavaScript developers for the front-end and, say, Python developers for the back-end. If there's a large backlog in back-end tasks, front-end developers wouldn't be able to help (unless they also know Python). This makes resource allocation more difficult for project managers. But if everyone develops in JavaScript, then this problem becomes null.

Furthermore, using JavaScript for the entire stack makes the development process more efficient. Apart from the efficiencies gained by avoiding context switching, a single developer can now develop an entire feature from start to finish, as they can code both the front- and back-end.

As Node.js and SPAs have became more popular, more and more JavaScript libraries are being written every day. At the time of writing, over 775,000 packages are listed on npmjs.com, the de facto package manager for JavaScript. These include libraries for handling time and date (moment.js), utility libraries (lodash), and even a deep learning library (convnetjs).

npm packages were originally only meant to be installed and run by server-side Node.js; however, tools such as Browserify and Webpack allowed us to bundle these dependencies and send them to the client. Now, many npm packages can be used in both the front- and back-end.

Likewise, by using JavaScript across your entire stack, you can encapsulate common logic and use it across both environments. For example, authentication checks should be performed on both the server (for security reasons) as well as the client (to ensure performance by preventing unnecessary requests).

If JavaScript is used for front- and back-end code, then the code can be shared and reused. If, however, we use Python in the back-end, then the same logic must be duplicated in JavaScript. This violates the Don't Repeat Yourself (DRY) principle and makes our development process slower and more error-prone.

The project also becomes harder to maintain. Now, when we need to make changes to the code, we must update it twice, in two different languages, possibly across two different projects; both projects may also need to be deployed at the same time.

Therefore, using JavaScript in the front-end and Node.js in the back-end allows you to improve maintainability, reduce compatibility issues, and conserve manpower and development time.

In this chapter, we described the evolution of web applications from using the client-server model to SPAs, and how advances in JavaScript engines facilitated this transformation. Then, we discussed the benefits of using JavaScript across the stack, focusing on the topics of context switching and shared code.

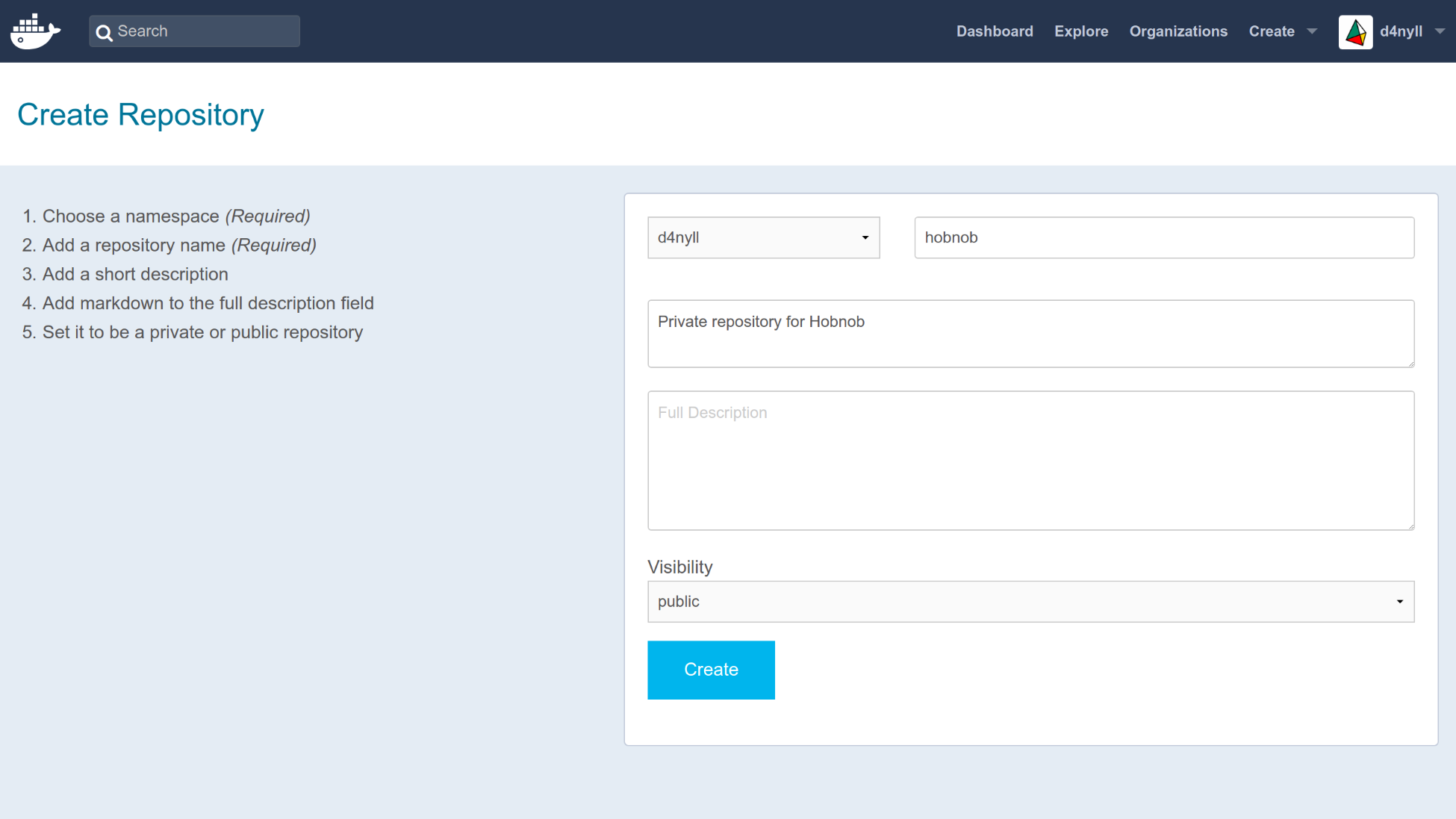

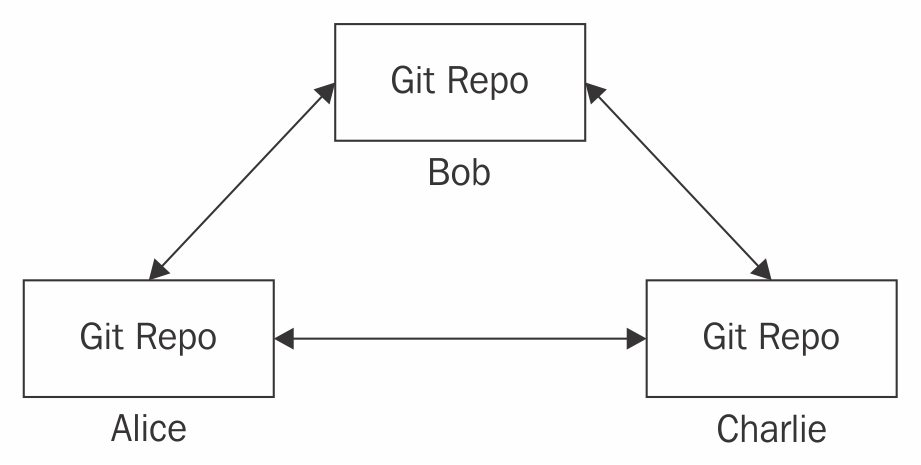

In this book, starting from Chapter 4, Setting Up Development Tools, we're going to be building a very simple user directory, which we've randomly named hobnob. We need a way for us to keep a versioned history of our code, so that if we've made some mistakes along the way, we can simply revert back to the last known good version and start again from there. This is known as version control (VC).

The simplest way to implement version control is to copy the entire codebase into date-stamped directories; however, this is tedious and may take up a lot of disk space. Instead, we can use a Version Control System (VCS) that'll manage these versions for us. We simply have to instruct the VCS when to create a snapshot of our code, and it will keep that version.

There have been many implementations of VCS, starting in 1972 with Source Code Control System (SCCS), which was superseded by Revision Control System (RCS, released in 1982), Concurrent Versions System (CVS, released in 1990), and Apache Subversion (SVN, released in 2000). Nowadays, we mainly use Git (released in 2005), a type of VCS known as Distributed VCS (DVCS).

Git was created by Linus Torvalds, who's also the creator of the Linux kernel. It is used to track changes in the development of the Linux kernel, as well as the tens of millions of repositories currently on GitHub. In this chapter, we will guide you through setting up and configuring Git, as well as explaining basic Git concepts, such as:

First, we must install Git.

Git is available for macOS, Windows, and Linux. You can find download instructions for Git at https://git-scm.com/downloads. Since we are using Ubuntu, the git package will be available from our distribution's package manager, Advanced Packaging Tool (APT). We should run sudo apt update to ensure that the list of repositories available to APT is up to date, before installing the git package:

$ sudo apt update

$ sudo apt-get install git

Git is now available as the git command-line interface (CLI).

Next, create a directory, named hobnob, to house our project. Then, navigate inside and run git init. This will allow Git to start tracking changes to our project; a project tracked by Git is also known as a repository:

$ mkdir -p ~/projects/hobnob

$ cd ~/projects/hobnob/

$ git init

Initialised empty Git repository in ~/projects/hobnob/.git/

Running git init creates a .git directory, which holds all version-control-related information about the project. When we interact with Git using its CLI, all it's doing is manipulating the content of this .git directory. We usually don't have to care about the contents of the .git directory, as we can interact with Git purely through the CLI.

We can configure Git using the git config command. This command will manipulate the .git/config file on our behalf. In fact, if we print the content of the .git/config file, you'll see that it is similar to the output of the git config command:

$ cd ~/projects/hobnob/

$ cat .git/config

[core]

repositoryformatversion = 0

filemode = true

bare = false

logallrefupdates = true

$ git config --list --local

core.repositoryformatversion=0

core.filemode=true

core.bare=false

core.logallrefupdates=true

To configure Git, we must first understand that there are three scopes, or levels, of configurations, each with a corresponding configuration file stored at different locations:

The local configuration settings will override the global settings, which, in turn, override the system settings.

When we ask Git to take a snapshot of our code (also called committing), Git will record several pieces of information, such as the time and author of the commit. The information about the author is saved as Git configurations, which saves us from having to re-type them each time we commit.

By default, adding/updating the configuration would write to the local config file. However, since you are going to be the only person using your user account on your machine, it's better to set the user settings in the global configuration file:

$ git config --global user.name "Daniel Li"

$ git config --global user.email "dan@danyll.com"

This will cause future commits to be, by default, identified as "Daniel Li" whose email address is "dan@danyll.com".

We have now successfully set up Git and configured our user.

For the remainder of this chapter, we will use dummy files to illustrate how Git works and the workflow we will follow. Everything you do for the rest of this chapter should be viewed as an educational exercise, and can be discarded afterward. At the beginning of the next chapter, we will start our project again from scratch, and you will use the things you learned in this chapter to keep your code base's history organized!

The primary purpose of Git is to keep a history of changes, or revisions. To illustrate this, let's create a simple file and commit it to the history of the repository.

First, let's confirm our repository's Git history by running git log, which shows a history of past commits:

$ git log

fatal: your current branch 'master' does not have any commits yet

The error correctly informs us that there are currently no commits. Now, let's create a short README.md file, which represents the first change we want to commit:

$ cd ~/projects/hobnob/

$ echo -e "# hobnob" >> README.md

We've created our first file and thus made our first change. We can now run git status, which will output information about the current state of our repository. We should see our README.md file being picked up by Git:

$ git status

On branch master

Initial commit

Untracked files: (use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

README.md

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

The output tells us that we are on the default master branch (more on branching later), and that this is our initial commit—we have not committed anything to the repository yet. It then says we have untracked files. To understand what that means, we must understand the different states that a file can be in with Git.

In Git, every file can be in one of two generic states: tracked and untracked.

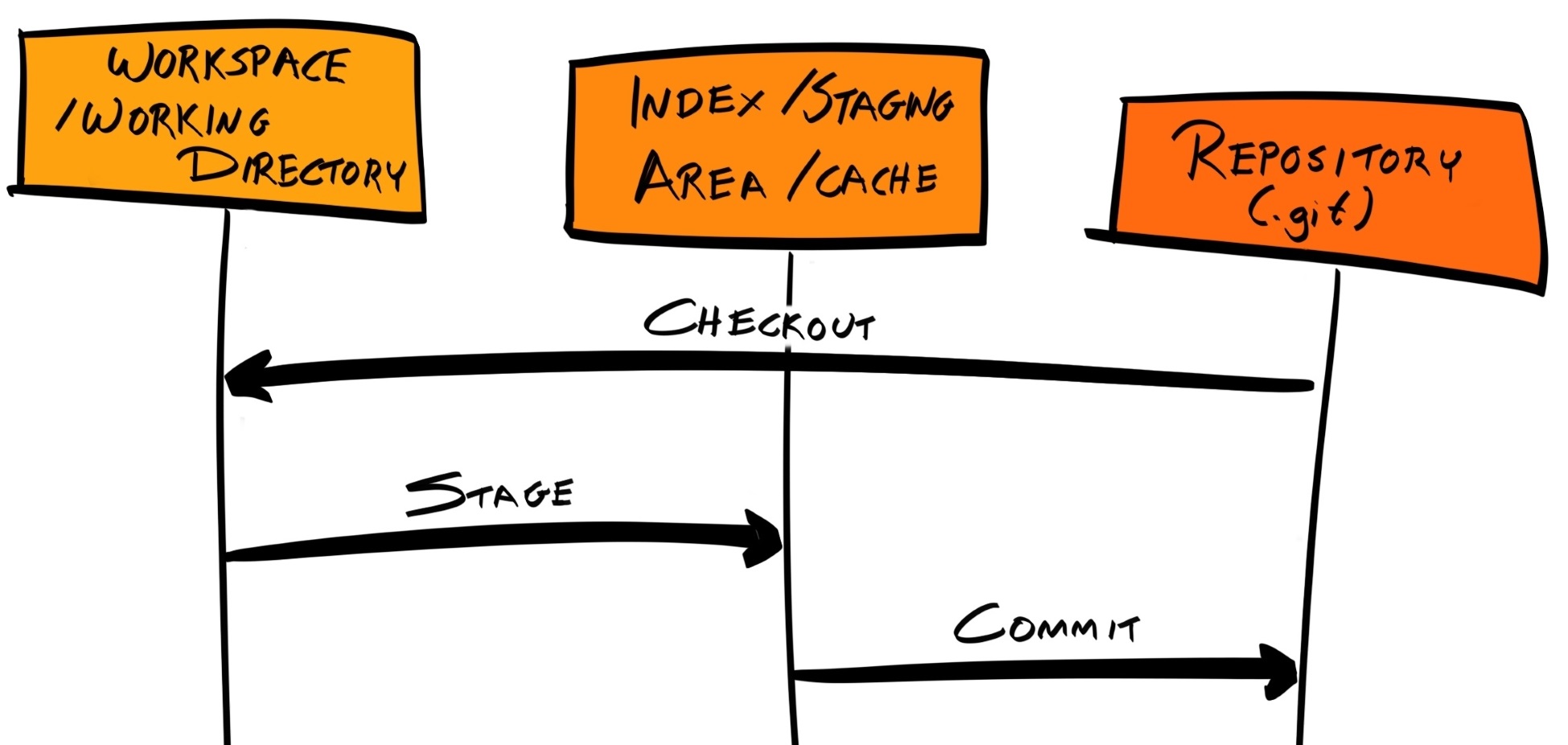

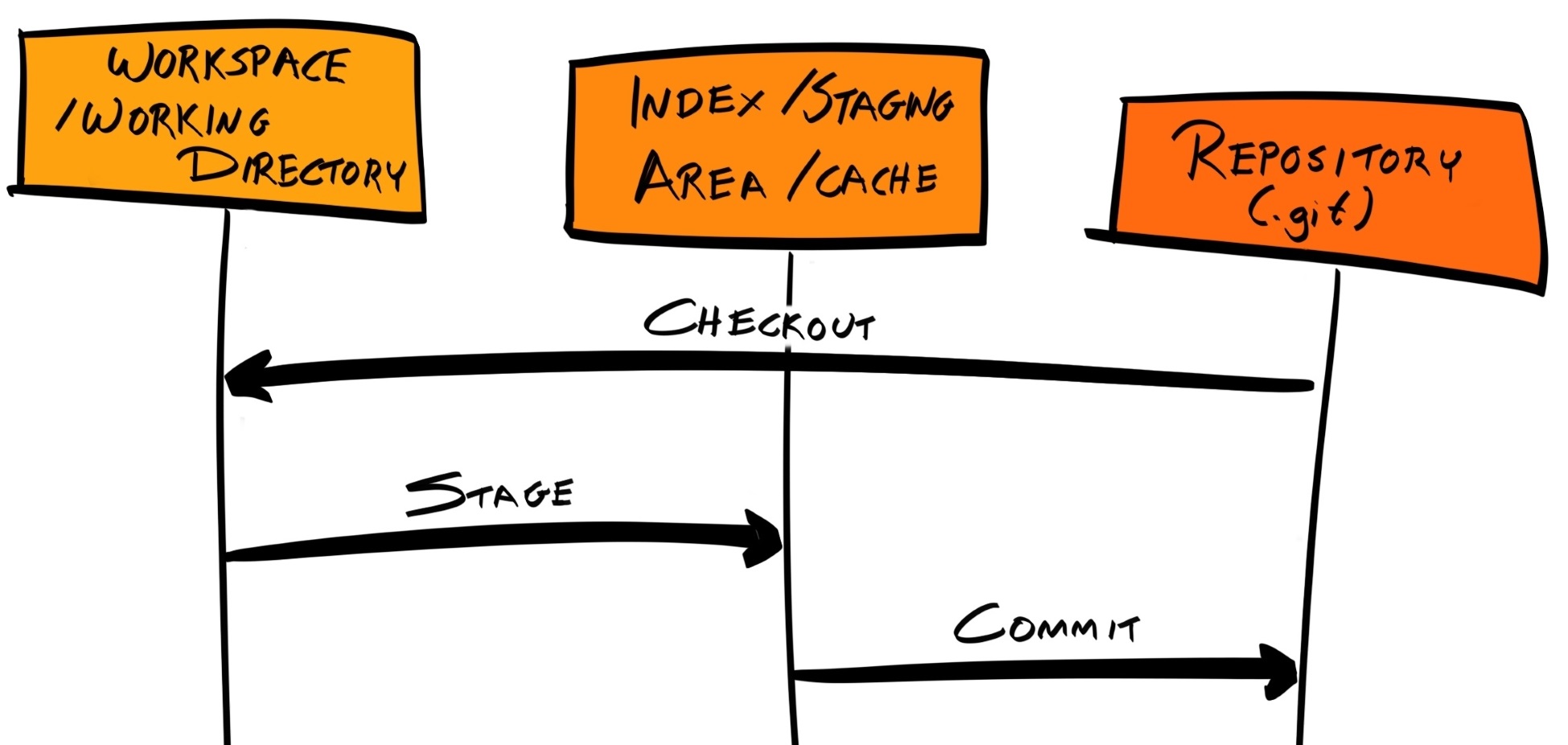

Initially, all files exists in the workspace (also known as working tree or working directory) and are in the untracked state. These untracked files are not part of the repository, and Git won't pick up changes made to them. When we run git status, Git sees that there are files in our workspace that are untracked (not part of the repository) and asks whether we want to add them to the repository. When we commit a new file to the repository using git add and git commit, it transitions from untracked to tracked:

$ git add README.md

$ git commit -m "Initial commit"

[master (root-commit) 6883f4e] Initial commit

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 README.md

README.md is now part of the repository and is in the tracked state.

We can confirm this by looking at the Git commit history of the repository with the git log command:

$ git log

commit 9caf6edcd5c7eab2b88f23770bec1bd73552fa4a (HEAD -> master)

Author: Daniel Li <dan@danyll.com>

Date: Fri Dec 8 12:29:10 2017 +0000

Initial commit

To be more precise, the tracked state can be further subdivided into three substates: modified, staged, and committed. Our README.md file is in the committed state.

Git will pay attention to all the tracked files; if we modify any of them (which includes deletions and renames), they will change their state from committed to modified:

$ echo "A very simple user directory API with recommendation engine" >> README.md

$ git status

On branch master

Changes not staged for commit:

modified: README.md

Modified files, alongside any untracked files, will be listed when we run git status. Modified files can be committed in the same manner as untracked files:

$ git add README.md

$ git commit -m "Update README.md"

[master 85434b6] Update README.md

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

You might be wondering why we had to run git add before we ran git commit. git add places the untracked or modified file into what is known as the staging area, which is also known as the index or cache. When a file is placed into the staging area, it is in the staged state. When we commit, only changes in the staging area are added to the repository; changes that remain in the workspace are not committed.

By having a staging area, we can git add multiple related changes and git commit them all at the same time—as a single commit.

Here, the staging area acts as a temporary environment to collect these related changes. For example, if we add a new feature into our application, we should also document this in our README.md. These changes are related to each other and should be committed together:

$ echo "console.log('Hello World')" >> index.js

$ echo -e "# Usage\nRun \`node index.js\`" >> README.md

$ git add index.js README.md

$ git commit -m "Add main script and documentation"

[master cf3221a] Add main script and documentation

2 files changed, 3 insertions(+)

create mode 100644 index.js

Let's quickly summarize what we've learned so far:

So far, we have been adding changes sequentially to the repository, resulting in a history with a linear structure. But what if you, or your team, want to work on different features/multiple tasks at the same time? If we continue with our current workflow, the Git commit history is going to look disjointed:

Here, we have commits relating to bug fixes interleaved between commits relating to features. This is not ideal. Git branches were created to deal with this issue.

As we've briefly mentioned, the default branch is called master, and we've been adding commits to this branch up to this point.

Now, when we develop a new feature or fix a particular bug, rather than adding those commits directory to master, we can instead create a branch from a certain commit from master. Any new commits to these bug fix and/or feature branches will be grouped together in a separate branch in the history tree, which does not affect the master branch. If and when the fix or feature is complete, we can merge this branch back into master.

The end result is the same, but the Git history is now much easier to read and understand. Furthermore, branches allow you to write and commit experimental code in an isolated part of the repository, so your changes, which may introduce new bugs and regressions, won't affect others until they have been tested and peer-reviewed.

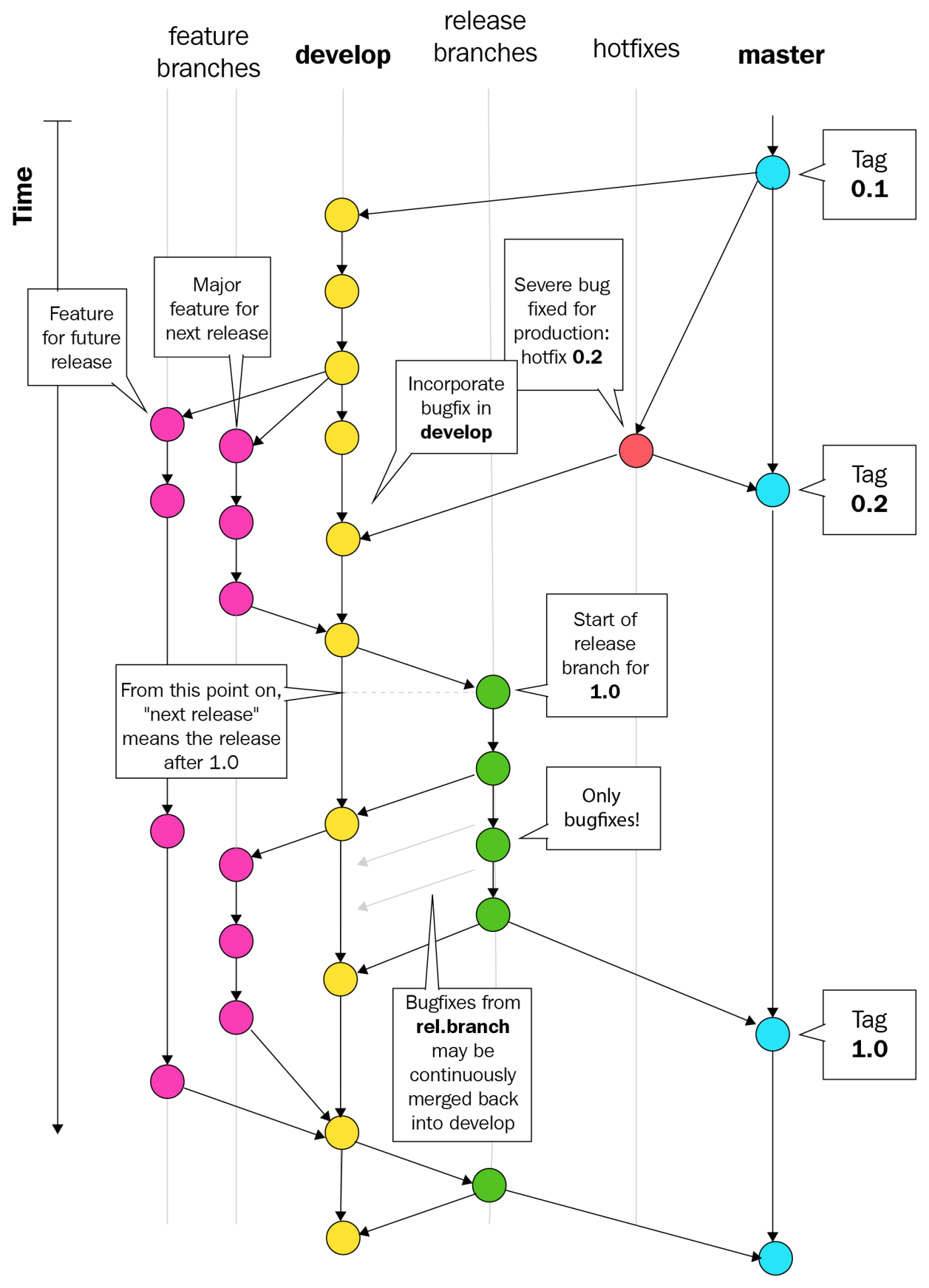

The workflow we described is an example of a branching model, which is just a term that describes how you structure your branches. As you can imagine, there are many branching models, and most are more complex than the one we've outlined.

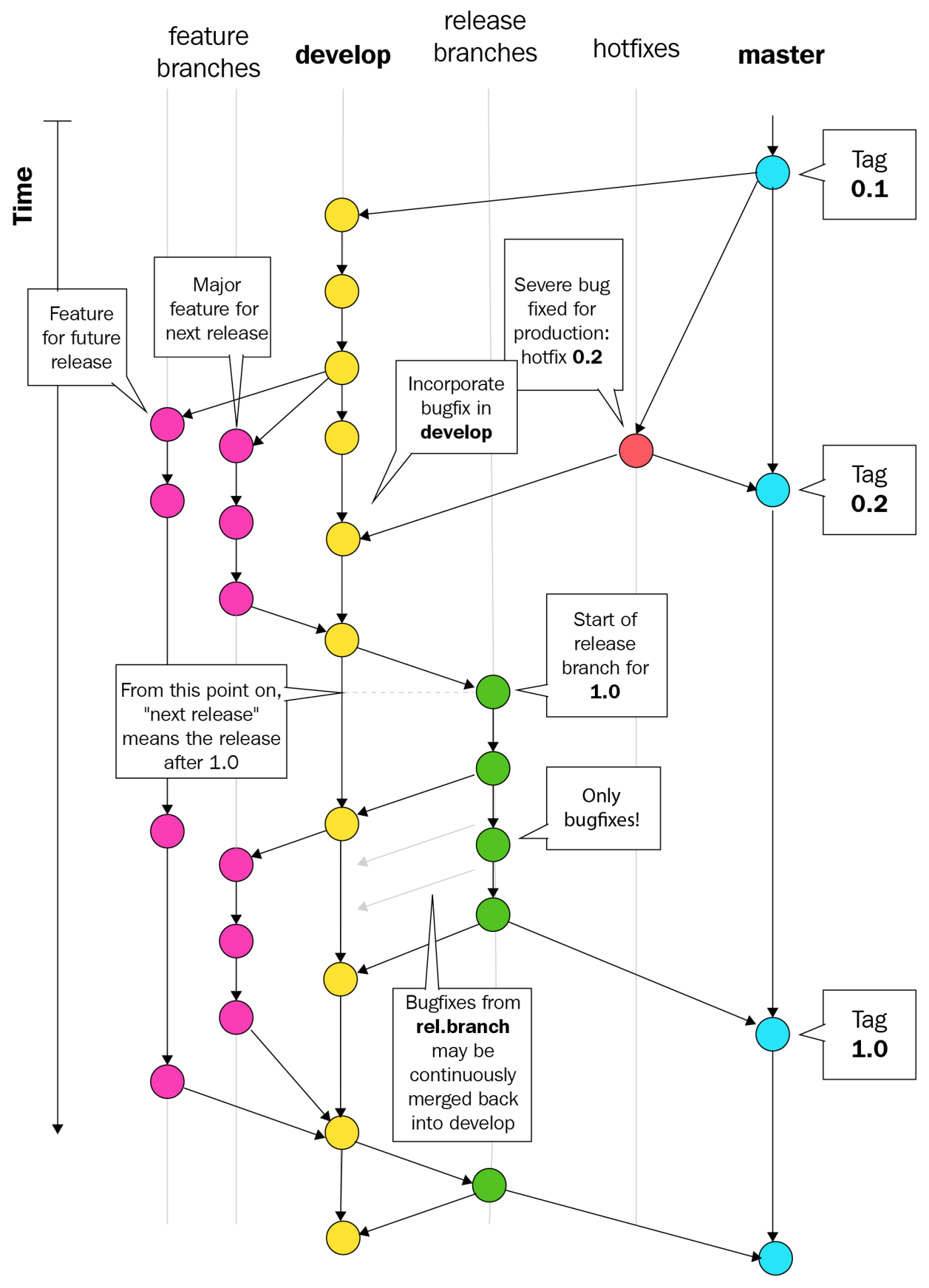

For this book, we will follow a branching model put forward by Vincent Driessen in his article A successful Git branching model, but you're free to explore other models and use the one that makes sense to you. The most important thing is that you and your team stick to the model consistently, so everyone on the team knows what is expected of them.

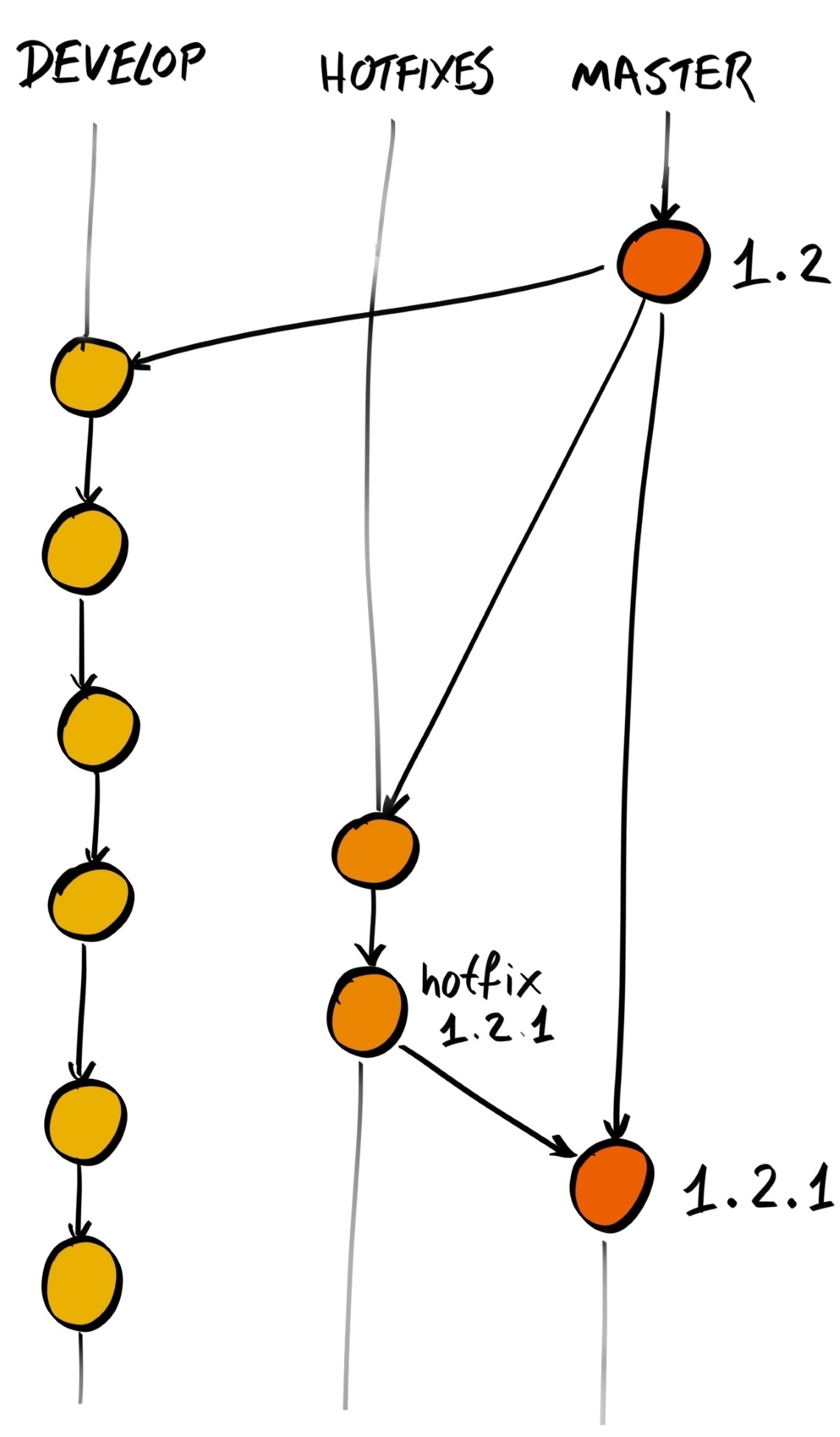

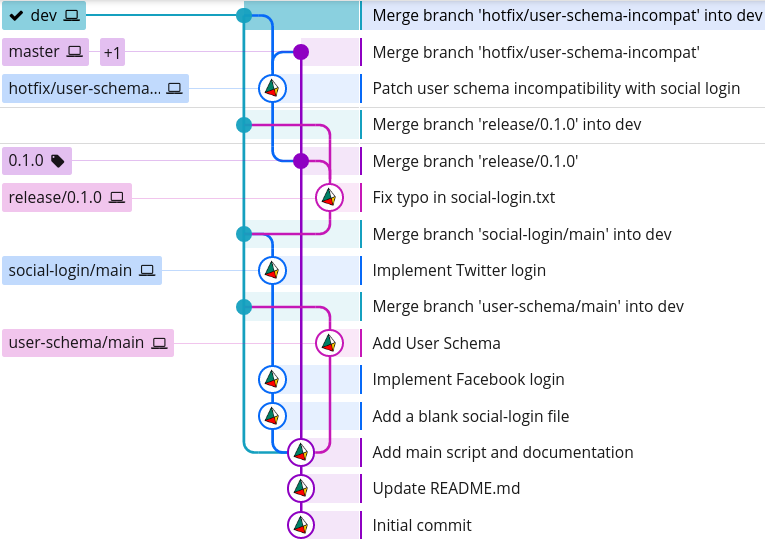

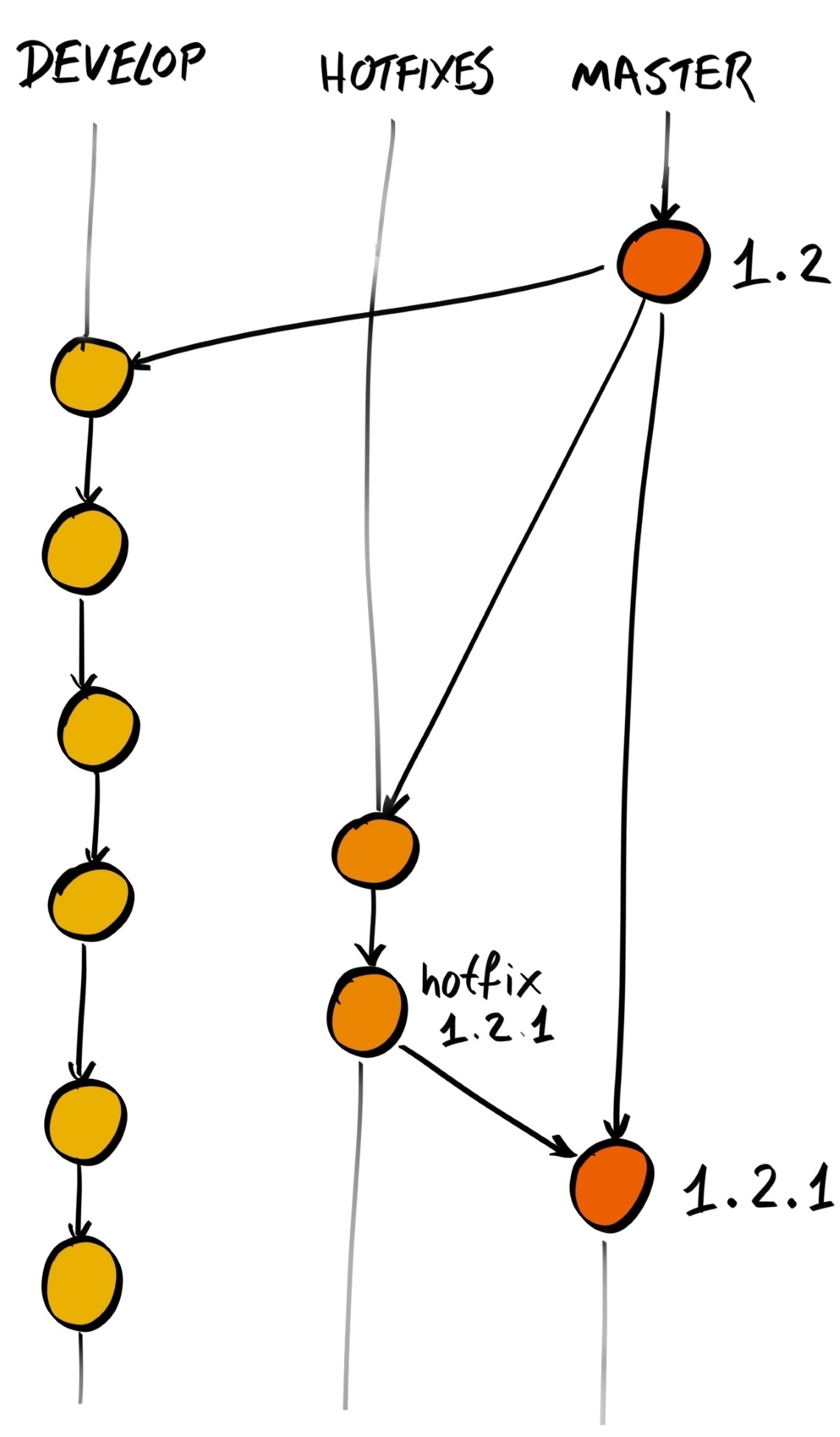

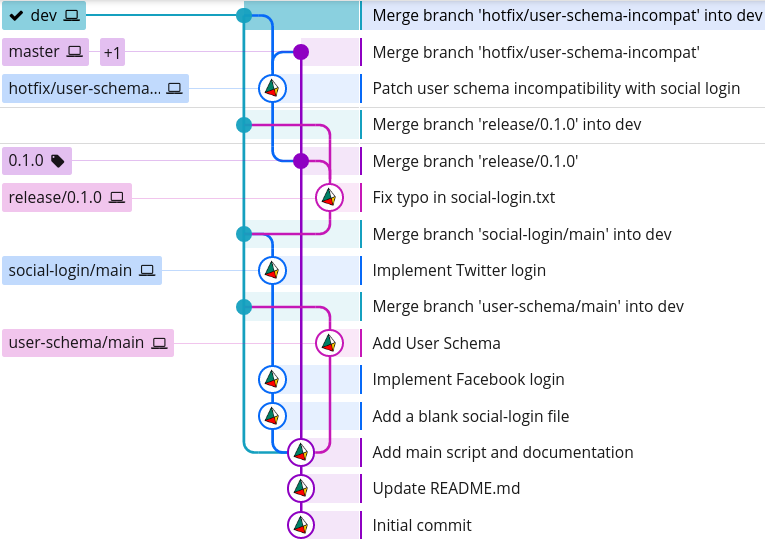

Driessen provided a detailed diagram of how his model works:

In Driessen's model, there are two permanent branches:

There are also other non-permanent branches:

To implement the Driessen Model, we must first create the dev branch from the master branch. To check which branch we are currently on, we can run git branch --list or simply git branch:

$ git branch

* master

This returns a list of all branches, with an asterisk (*) next to the currently active branch, which is currently master. To create a new dev branch from the current branch, we can run git branch dev.

However, we are instead going to run git checkout -b dev master, which creates a new branch and makes it active at the same time:

$ git checkout -b dev master

Switched to a new branch 'dev'

$ git branch

* dev

master

Any new features should be developed by branching off dev. Be sure to name the feature branch so that it clearly indicates the feature being worked on. For example, if you're working on the social login feature, name your branch social-login:

$ git branch

* dev

master

$ git checkout -b social-login dev

Switched to a new branch 'social-login'

If that feature has sub-features, you may create sub-branches from the main feature branch. For example, the social-login branch may include facebook-login and twitter-login sub-branches.

There are multiple valid ways to name these sub-branches, but the most popular convention uses grouping tokens, with various delimiters. For example, our Facebook and Twitter login sub-branches can be grouped under the social-login grouping token, with a period (.) as a delimiter, and a sub-token such as facebook or twitter:

$ git checkout -b social-login.facebook social-login

Switched to a new branch 'social-login.facebook'

$ git branch

dev

master

social-login

* social-login.facebook

You can use almost anything as a delimiter; the comma (,), hash (#), and greater-than sign (>) are all valid delimiters. However, there are several rules outlined under the git-check-ref-format part of the documentation that give valid reference names. For example, the following characters are unavailable: space, tilde (~), caret (^), colon (:), question mark (?), asterisk (*), and open bracket ([).

Most conventions I have encountered use a forward slash (/) as the delimiter, and so we do the same here. However, this poses a problem because branches are stored as text files under .git/refs/heads. If we create a sub-branch called social-login/facebook, then it'd need to be created at .git/refs/heads/social-login/facebook, but this is impossible in our case because the social-login name is already used for the file, and thus cannot act as a directory at the same time:

$ git checkout -b social-login/facebook social-login

fatal: cannot lock ref 'refs/heads/social-login/facebook': 'refs/heads/social-login' exists; cannot create 'refs/heads/social-login/facebook'

Therefore, when we create a new feature branch, we need to provide a default sub-token, such as main. With that in mind, let's delete our current feature branches and create them again with the main sub-token:

$ git checkout dev

$ git branch -D social-login social-login.facebook

$ git checkout -b social-login/main dev

$ git branch

dev

master

* social-login/main

We are now on the social-login/main feature branch, and can start developing our social login feature.

First, let's create that file and commit it to the social-login/main branch:

$ touch social-login.txt

$ git add -A && git commit -m "Add a blank social-login file"

Now, we are going to create a sub-feature branch and develop our Facebook login feature:

$ git checkout -b social-login/facebook social-login/main

$ echo "facebook" >> social-login.txt

$ git add -A && git commit -m "Implement Facebook login"

Now, do the same for the Twitter login feature, making sure to branch from the main feature branch:

$ git checkout -b social-login/twitter social-login/main

$ echo "twitter" >> social-login.txt

$ git add -A && git commit -m "Implement Twitter login"

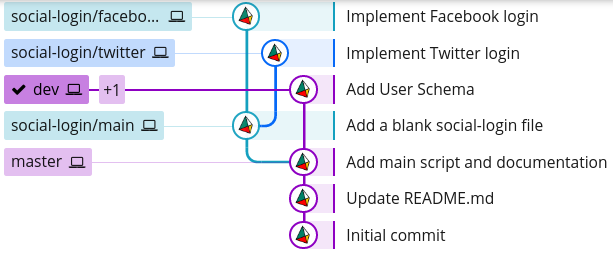

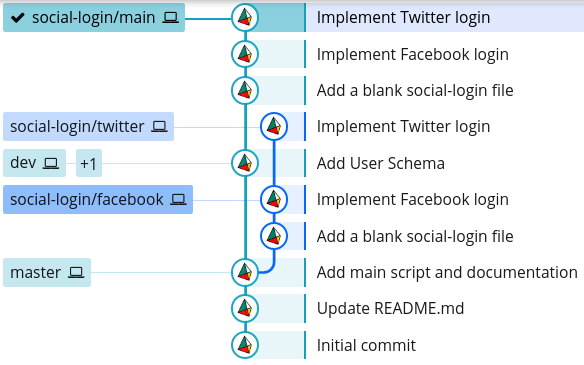

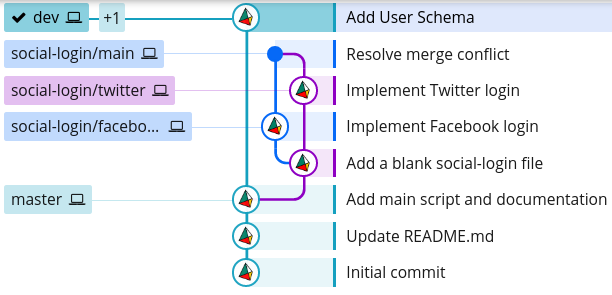

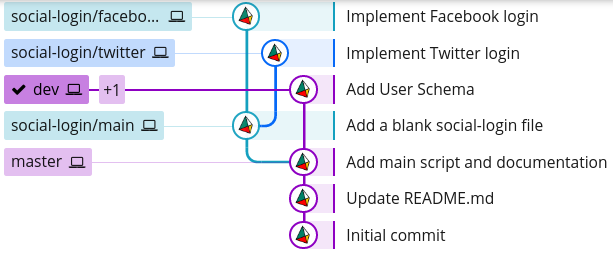

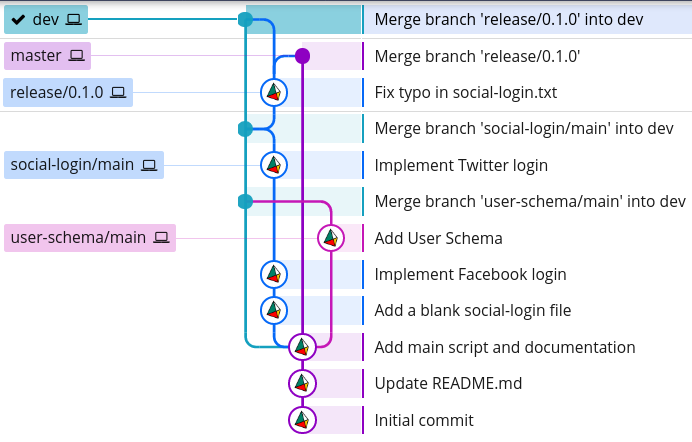

We now have two sub-feature branches, one main feature branch, one dev branch, and our original master branch:

$ git branch

dev

master

social-login/facebook

social-login/main

* social-login/twitter

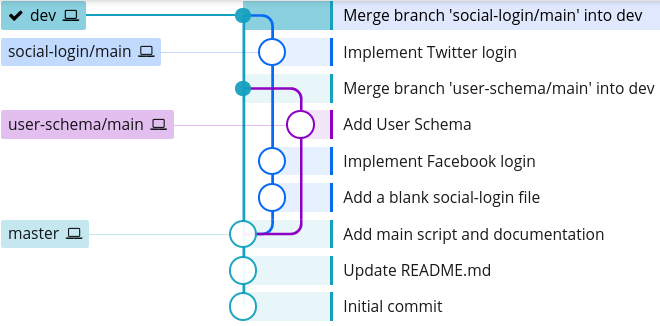

We have developed our Facebook and Twitter login features on two separate sub-feature branches; how can we get these changes back onto the master branch? Following the Driessen Model, we must merge the two sub-feature branches onto the main feature branch, then merge the feature branch into the dev branch, and then create a release branch off dev and merge that release branch into master.

To get started, let's merge the social-login/facebook branch into the social-login/main branch using git merge:

$ git checkout social-login/main

$ git merge social-login/facebook

Updating 8d9f102..09bc8ac

Fast-forward

social-login.txt | 1 +

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

Git will attempt to automatically merge the changes from the social-login/facebook branch into the social-login/main branch. Now, our branch structure looks like this:

$ git log --graph --oneline --decorate --all

* 9204a6b (social-login/twitter) Implement Twitter login

| * 09bc8ac (HEAD -> social-login/main, social-login/facebook) Implement Facebook login

|/

* 8d9f102 Add a blank social-login file

* cf3221a (master, dev) Add main script and documentation

* 85434b6 Update README.md

* 6883f4e Initial commit

Next, we need to do the same for our Twitter login sub-feature. However, when we attempt the merge, it fails due to a merge conflict:

$ git checkout social-login/main

$ git merge social-login/twitter

Auto-merging social-login.txt

CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in social-login.txt

Automatic merge failed; fix conflicts and then commit the result.

A merge conflict occurs when the changes from the two branches being merged overlap each other; Git doesn't know which version is the most appropriate version to move forward with, and so it does not automatically merge them. Instead, it adds special Git markup into the file where the merge conflict occurs and expects you to manually resolve them:

<<<<<<< HEAD

=======

>>>>>>> social-login/twitter

The part between <<<<<<< HEAD and ======= is the version on our current branch, which is social-login/main; the part between ======= and >>>>>>> social-login/twitter is the version on the social-login/twitter branch.

We must resolve this merge conflict before the merge is complete. To do that, we simply need to edit the file to the version we want, and remove the Git-specific sequences. In our example, we want to add the text for twitter after facebook, so we would edit the file to become the following:

Now the conflict is resolved, we need to complete the merge by adding social-login.txt to the staging area and committing it:

$ git status

On branch social-login/main

You have unmerged paths.

Unmerged paths:

both modified: social-login.txt

$ git add -A && git commit -m "Resolve merge conflict"

[social-login/main 8a635ca] Resolve merge conflict

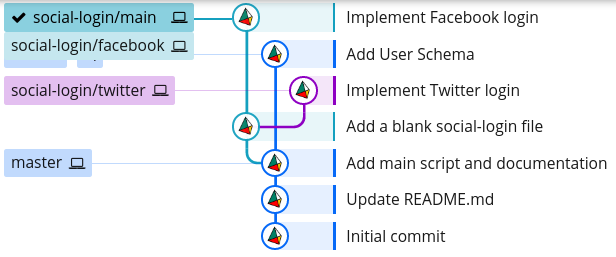

Now, if we look again at our Git history, we can see that we've implemented the Facebook and Twitter login features on two separate branches, and then merged them together in a separate commit (the one with the hash 37eb1b9):

$ git log --graph --oneline --decorate --all

* 37eb1b9 (HEAD -> social-login/main) Resolve merge conflict

|\

| * 9204a6b (social-login/twitter) Implement Twitter login

* | 09bc8ac (social-login/facebook) Implement Facebook login

|/

* 8d9f102 Add a blank social-login file

* cf3221a (master, dev) Add main script and documentation

* 85434b6 Update README.md

* 6883f4e Initial commit

The example we went through previously is very simple and a bit contrived. In a more realistic working environment, the dev branch will be very active: there will be many feature/bug fix branches that stem from dev and ultimately merge back into it. To illustrate how that can cause issues, and to show you how those issues can be mitigated, we're going back to the dev branch to create another feature branch; let's call it user-schema/main:

$ git checkout -b user-schema/main dev

Switched to a new branch 'user-schema/main'

Now, let's add a file, user-schema.js, which represents the entirety of our user schema feature:

$ touch user-schema.js

$ git add -A && git commit -m "Add User Schema"

[user-schema/main 8a31446] Add User Schema

1 file changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

create mode 100644 user-schema.js

Now, we can merge this feature branch back into dev:

$ git checkout dev

Switched to branch 'dev'

$ git merge user-schema/main

Updating cf3221a..8a31446

Fast-forward

user-schema.js | 0

1 file changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

create mode 100644 user-schema.js

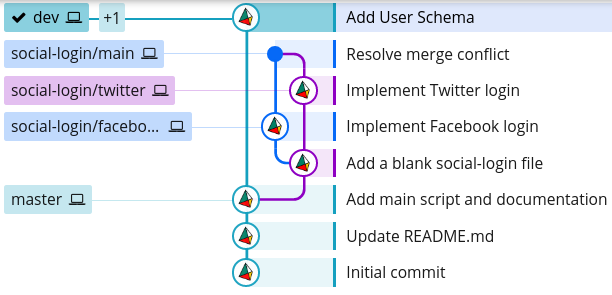

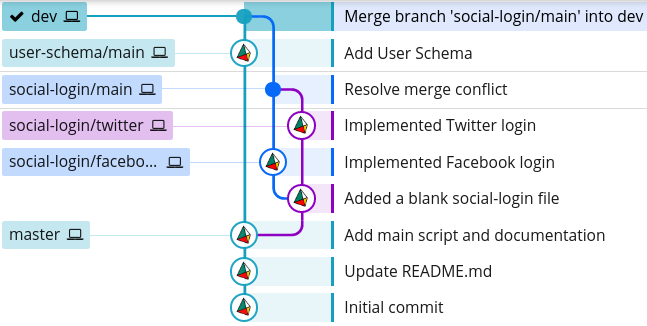

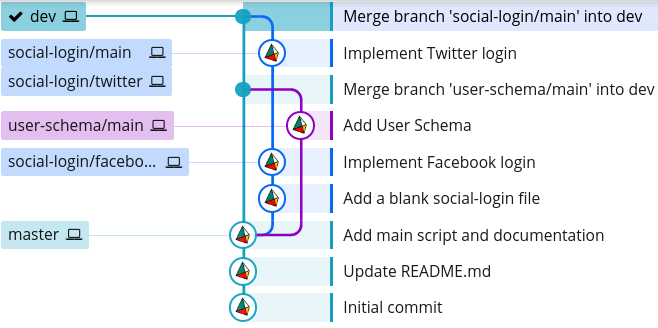

Our Git history tree now looks like this:

$ git log --graph --oneline --decorate --all

* 8a31446 (HEAD -> dev, user-schema/main) Add User Schema

| * 37eb1b9 (social-login/main) Resolve merge conflict

| |\

| | * 9204a6b (social-login/twitter) Implement Twitter login

| * | 09bc8ac (social-login/facebook) Implement Facebook login

| |/

| * 8d9f102 Add a blank social-login file

|/

* cf3221a (master) Add main script and documentation

* 85434b6 Update README.md

* 6883f4e Initial commit

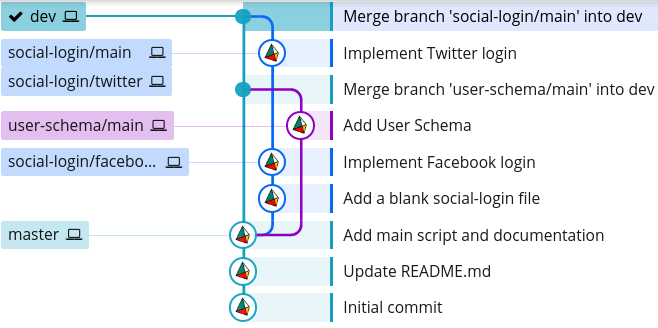

Now, we could merge our social-login/main branch back into dev, which will produce the following branch structure:

However, we should not do this because:

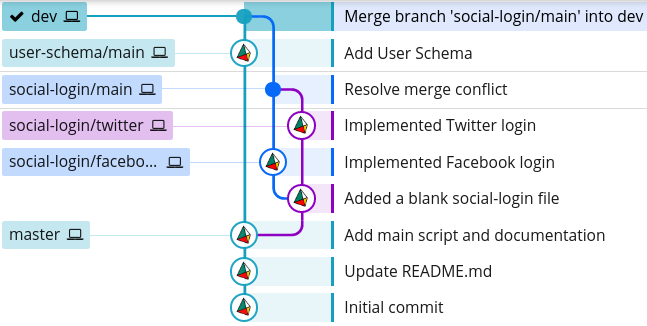

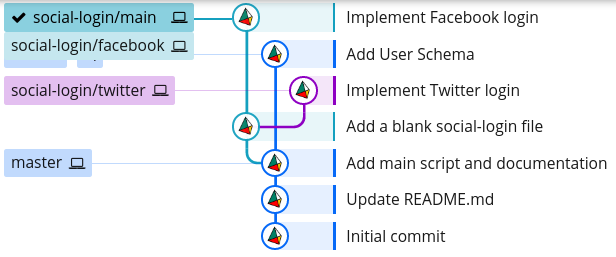

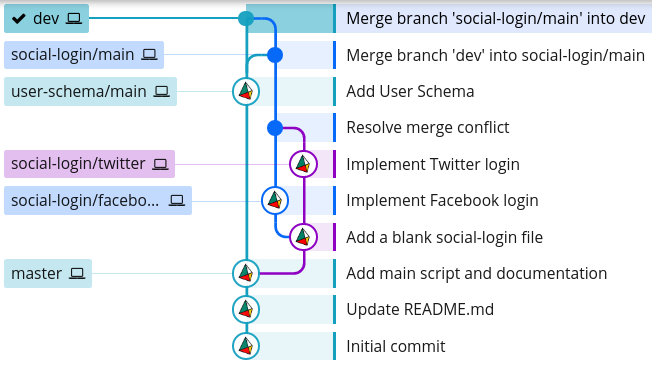

The first issue can be tackled by merging the dev branch into social-login/main, testing that everything works as normal, and then merging it back into dev:

$ git checkout social-login/main

$ git merge dev

$ git checkout dev

$ git merge social-login/main

This way, any bugs that arise due to the incompatibility of the branches will remain on the feature branch, and not on dev. This gives us a chance to fix these bugs before merging back into dev.

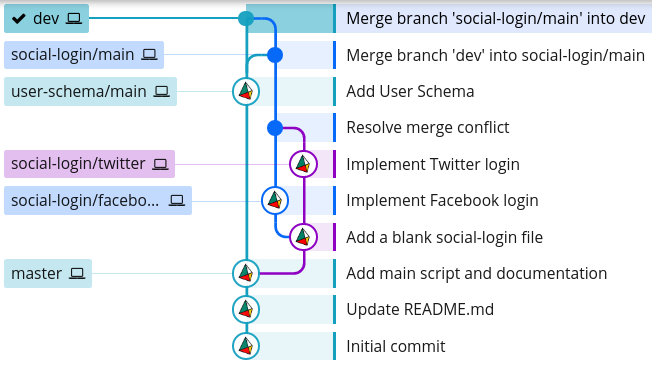

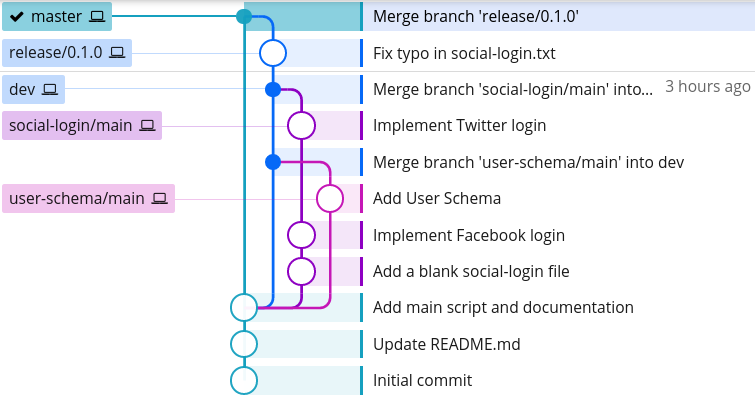

While this solved one issue, it exacerbated the other. Our Git history now looks like this:

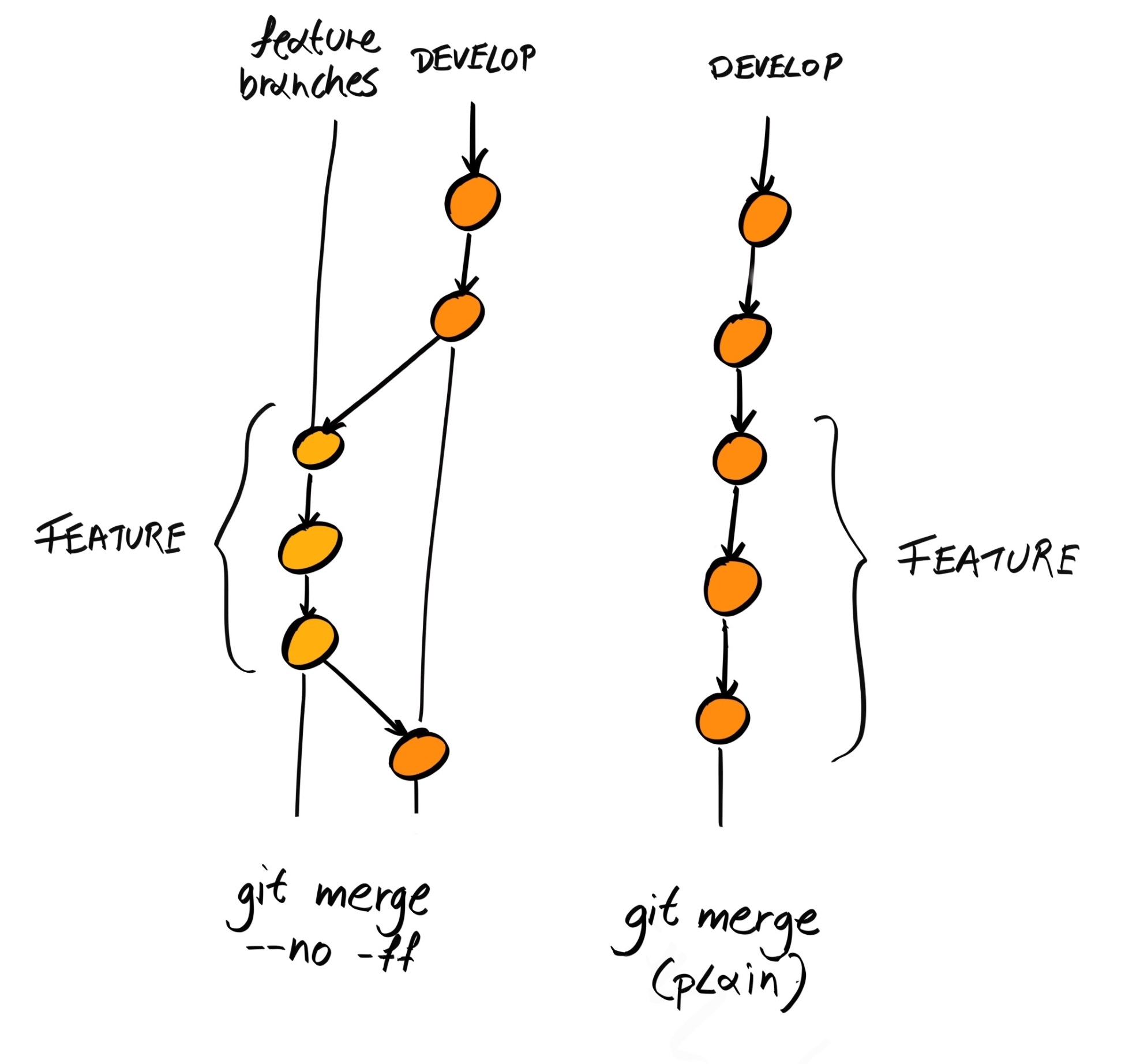

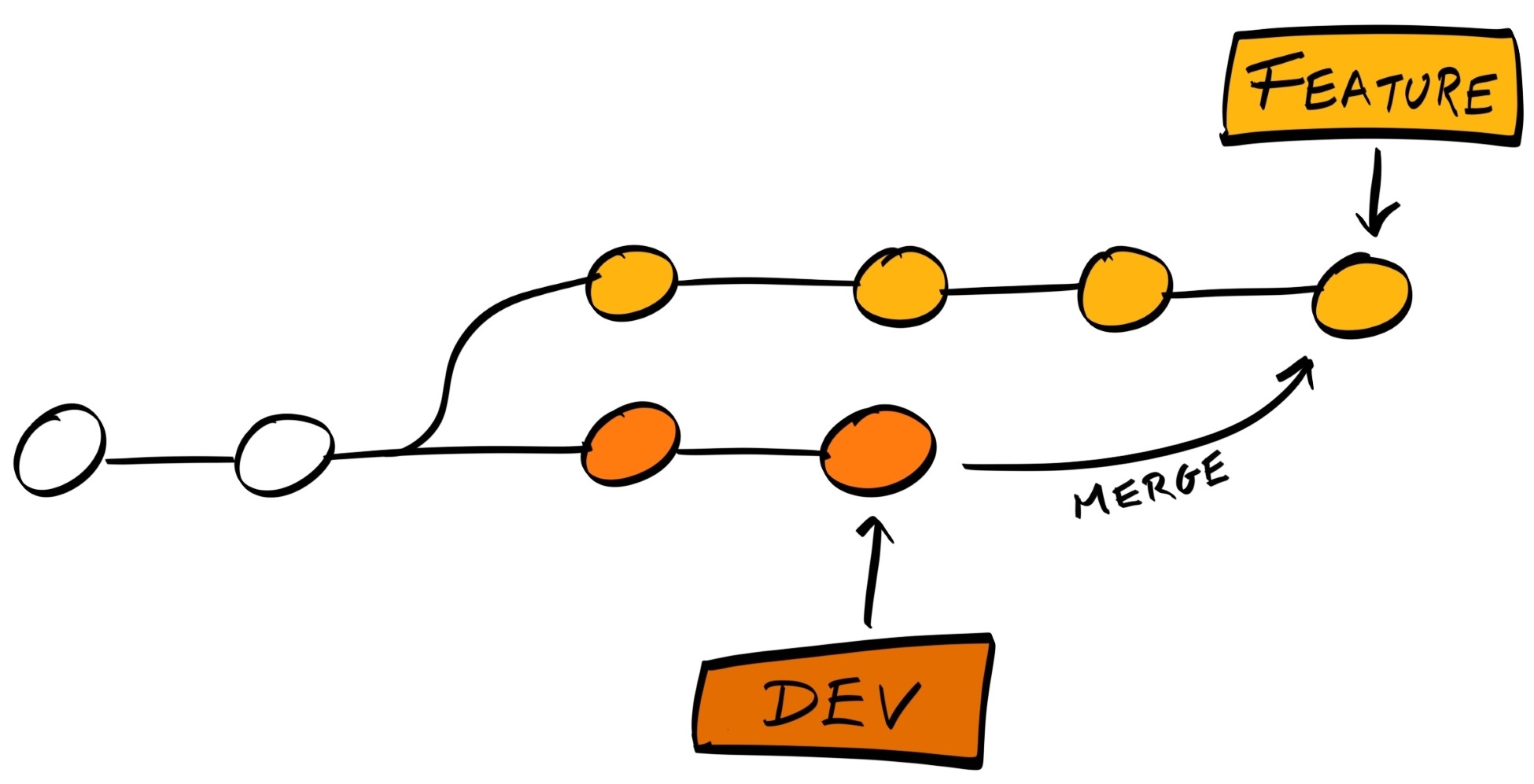

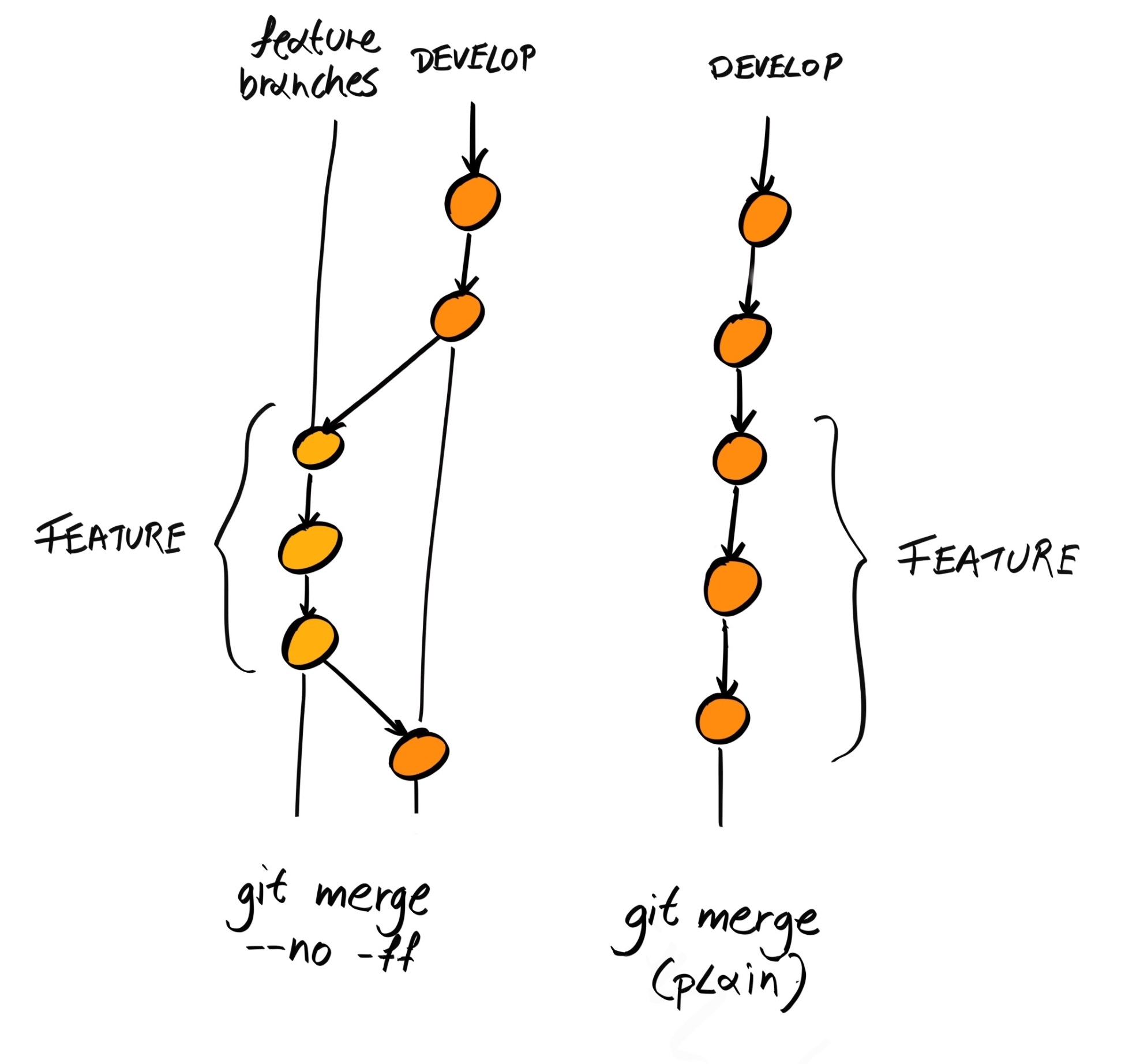

The reason our Git history looks so complicated is because git merge creates a separate commit for the merge. This is good because it doesn't alter the history of any of the branches; in other words, it is non-destructive:

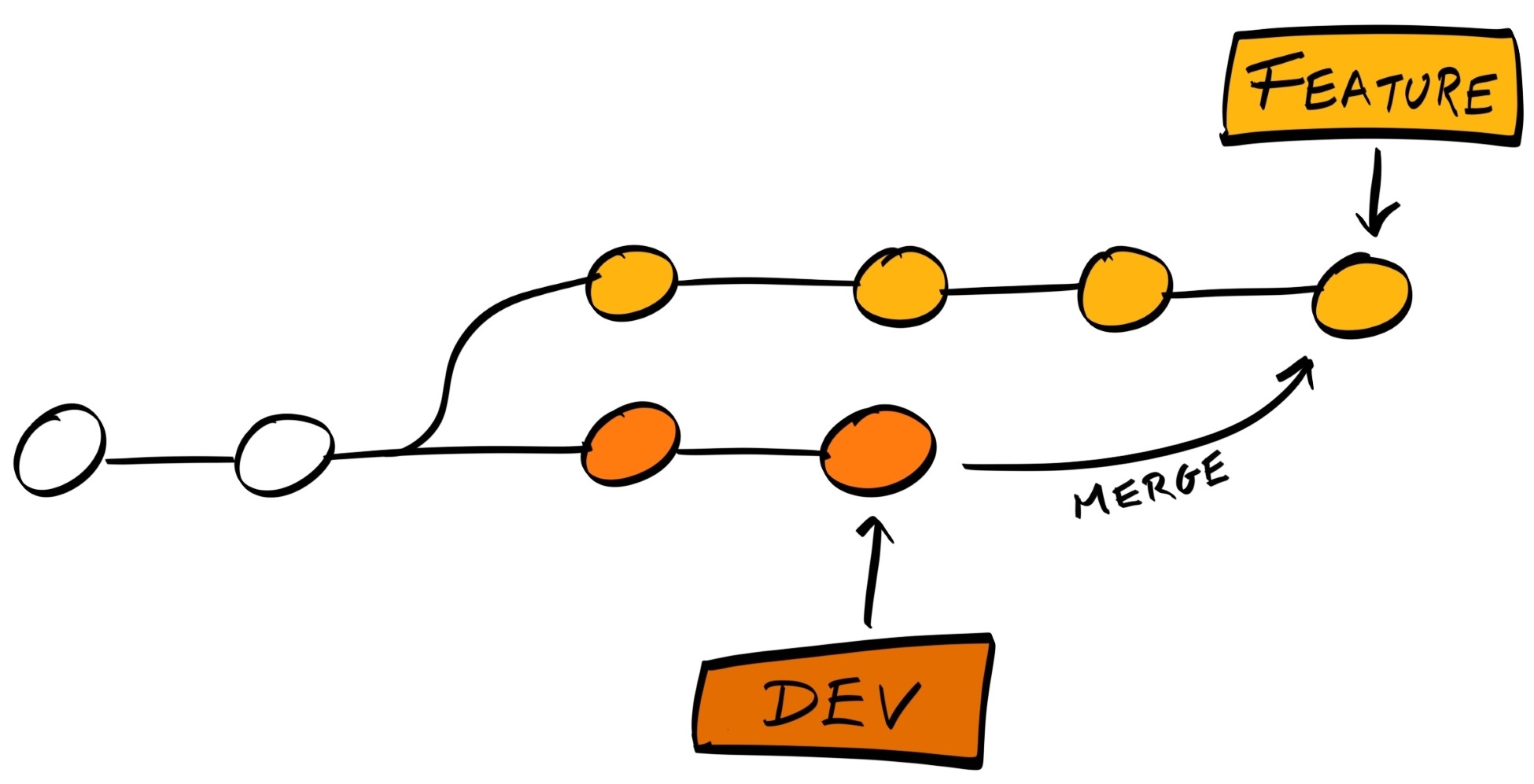

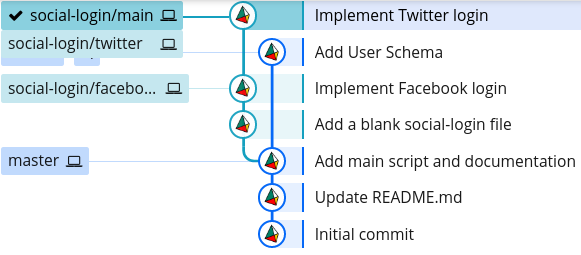

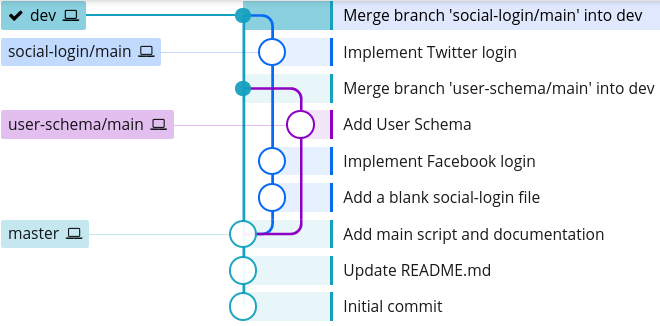

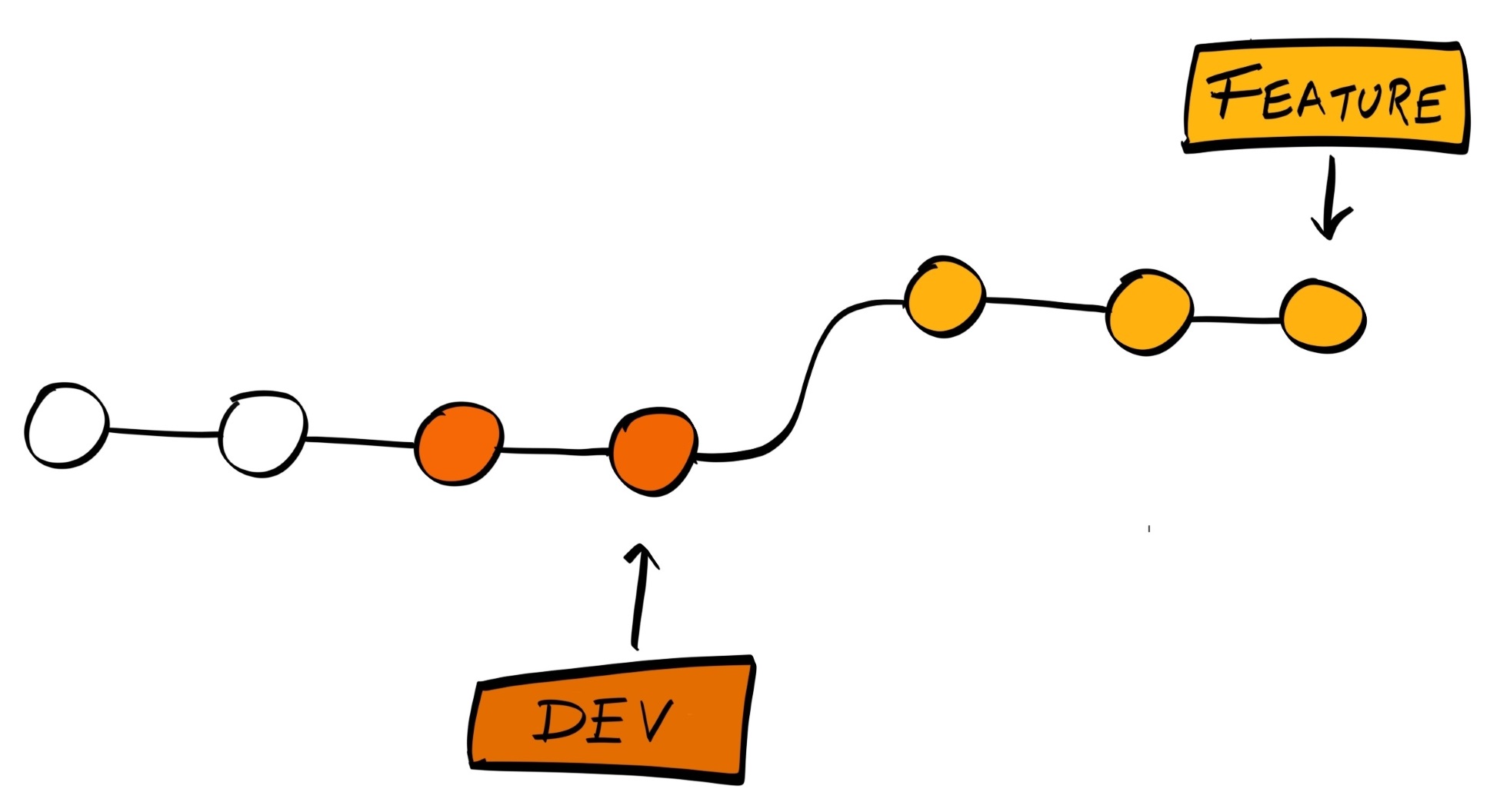

To prevent the complicated history tree we have here, Git provides an alternative command, rebase, that allows us to merge changes, as well as keep our history clean.

With git rebase, instead of creating a new commit for the merge, it will try to place the changes on the feature branch as if they were made directly after the last commit on the main branch:

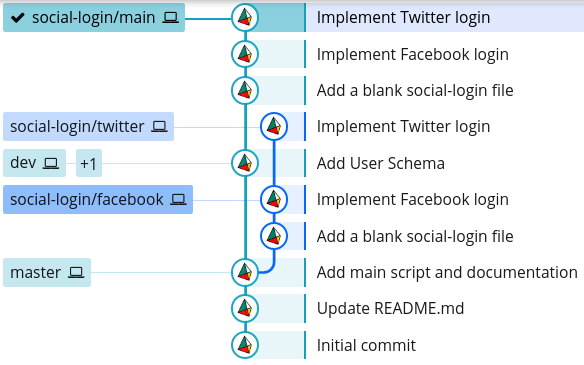

To see how we can work with rebase, let's repeat everything we've done so far, but using rebase instead of merge. Create a new directory and open your Terminal, then copy and paste the following commands (which will replicate everything we've done so far):

git init &&

echo -e "# hobnob" >> README.md &&

git add README.md && git commit -m "Initial commit" &&

echo "A very simple user directory API with recommendation engine" >> README.md &&

git add README.md && git commit -m "Update README.md" &&

echo "console.log('Hello World')" >> index.js &&

echo -e "# Usage\nRun \`node index.js\`" >> README.md &&

git add -A && git commit -m "Add main script and documentation" &&

git checkout -b dev master &&

git checkout -b social-login/main dev &&

touch social-login.txt &&

git add -A && git commit -m "Add a blank social-login file" &&

git checkout -b social-login/facebook social-login/main &&

echo "facebook" >> social-login.txt &&

git add -A && git commit -m "Implement Facebook login" &&

git checkout -b social-login/twitter social-login/main &&

echo "twitter" >> social-login.txt &&

git add -A && git commit -m "Implement Twitter login" &&

git checkout -b user-schema/main dev &&

touch user-schema.js &&

git add -A && git commit -m "Add User Schema" &&

git checkout dev &&

git merge user-schema/main

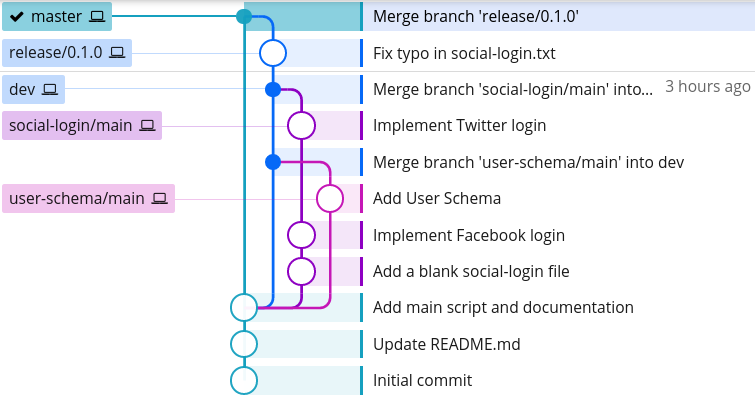

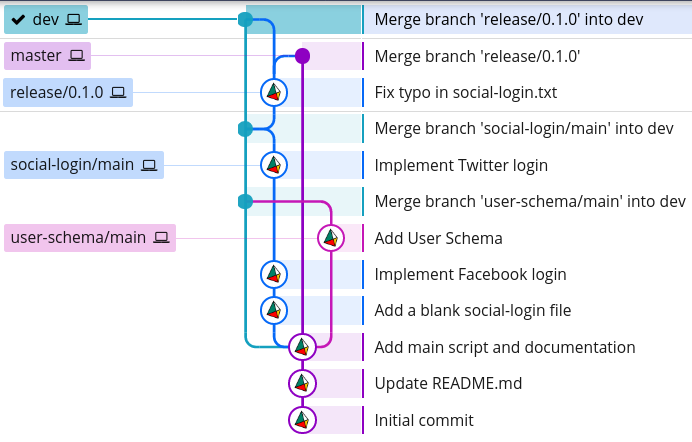

Our Git history tree now looks like this: