A perpetual debate rages over the exact process by which software vulnerabilities should be disclosed. For any vulnerability discovered in a piece of software, we can assign the roles of discoverer (of the vulnerability) and maintainer (of the software). In addition, we can specify a number of events, which may or may not take place, surrounding the discovery of any vulnerability. Some of these events are briefly described here. Please keep in mind that the entire vulnerability-disclosure process is hotly debated, and the following terms are by no means standardized or even widely accepted.

- Discovery

The time at which a vulnerability is initially discovered. For our purposes, we will also consider this to be the time at which an exploit for that vulnerability is initially developed.

- Notification

The time at which the software maintainer is initially made aware of the vulnerability within its product. This may coincide with discovery if the vendor happens to find the vulnerability itself.

- Disclosure

The time at which a vulnerability is made known to the public. This event can be muddied by the level of detail made available regarding the vulnerability. Disclosure may or may not be accompanied by the release or identification of working exploits. In some cases disclosure also serves as notification to the vendor.

- Mitigation

The time at which steps are published that, if followed, may prevent a user from falling victim to an existing exploit. Mitigation steps are work-around solutions for users awaiting the publication of a patch.

- Patch availability

The time at which the maintainer (or a third party) makes available a corrected version of the vulnerable software.

- Patch application

The time at which users actually install the updated, corrected software, rendering themselves immune (hopefully) to all known attacks that rely on the presence of the given vulnerability.

A wealth of papers are more than happy to tell you all about windows of vulnerability, obligations on the part of the discoverer and the maintainer, and exactly how much information should be disclosed and when that disclosure should take place. Getting to the point, it is common for disclosure to coincide with the availability of a patch.

In most cases, a vulnerability advisory is published in conjunction with the patch. The vulnerability advisory provides some level of technical detail describing the nature and severity of the problem that has been patched, but the level of detail is usually insufficient to use in developing a working exploit for the problem. Why anyone would want to develop a working exploit is another matter. Clearly some people are interested in exploiting computers that remain unpatched, and the faster an exploit can be developed, the greater their chance of exploiting more computers. In other cases, vendors may be interested in developing tools that scan for the presence of unpatched systems on networks or in developing techniques for real-time detection of exploitation attempts. In most cases, development of such tools requires a detailed understanding of the exact nature of the newly patched vulnerability.

Advisories may lack such essential information as the exact file or files that contain the vulnerability, the name or location of any vulnerable functions, and exactly what was changed within those functions. The patched files themselves, however, contain all the information that an exploit developer requires in order to develop a working exploit for the newly patched vulnerability. This information is not immediately obvious, nor is it clearly intended for the consumption of an exploit developer. Instead, this information is present in the form of the changes that were made in order to eliminate the underlying vulnerability. The easiest way to highlight such changes is to compare a patched binary against its unpatched counterpart. If we have the luxury of looking for differences in patched source files, then standard text-oriented comparison utilities such as diff can make short work of pinpointing changes. Unfortunately, tracking down behavioral changes between two revisions of a binary file is far more complicated than simple text file diffing.

The difficulty with using difference computation to isolate the changes in two binaries lies in the fact that binaries can change for several reasons. Changes may be triggered by compiler optimizations, changes to the compiler itself, reorganization of source code, addition of code unrelated to the vulnerability, and of course the code that patches the vulnerability itself. The challenge lies in isolating behavioral changes (such as those required to fix the vulnerability) from cosmetic changes (such as the use of different registers to accomplish the same task).

A number of tools designed specifically for binary diffing are available, including the commercial BinDiff from Zynamics;[190] the free Binary Diffing Suite (BDS) from eEye Digital Security;[191] Turbodiff,[192] also free and available from Core Labs (part of Core Security, makers of Core Impact[193]); and PatchDiff2[194] by Nicolas Pouvesle. Each of these tools relies on supplied IDA in one way or another. BinDiff and BDS make use of IDA scripts and plug-ins to perform initial analysis tasks on both the patched and the unpatched versions of the binaries being analyzed. Information extracted by the plug-ins is stored in a backend database, and each tool provides a graph-based display and can navigate through the differences detected during the analysis phase. Turbodiff and PatchDiff2 are implemented as IDA plug-ins and display their results within IDA itself. The ultimate goal of these tools is to quickly highlight the changes made to patch a vulnerability in order to understand why the code was vulnerable in the first place. Additional information on each tool is available on its respective website.

Representative of the free diffing tools, PatchDiff2 is an open source project offering compiled, 32- and 64-bit Windows versions of the plug-in along with subversion access to the plug-in source. Installing the plug-in involves copying the plug-in binaries into <IDADIR>/plugins.

The first step in using PatchDiff2 is to create two separate IDA databases, one for each of the two binaries to be compared. Typically one of these databases would be created for the original version of the binary, while the other database would be created for the patched version of the binary.

Name | PatchDiff2 |

Author | Nicolas Pouvesle |

Distribution | Source and binaries for IDA 5.7 |

Price | Free |

Description | Binary difference generation and display |

Information |

Invoking the plug-in typically involves opening the database for the original binary and then activating PatchDiff2 via the Edit ▸ Plugins menu or its associated hot key (default is ctrl-8). PatchDiff2 refers to the database from which you invoke the plug-in as IDB1, or the “first idb.” Upon activation, PatchDiff2 will ask to open the second database against which the currently open database will be compared; this database is known as IDB2, or the “second idb.” Once a second database has been selected, PatchDiff2 computes a number of identifying features for every function in each database including various types of signatures, hash values, and CRC values. Utilizing these features, PatchDiff2 creates three lists of functions titled Identical Functions, Unmatched Functions, and Matched Functions. Each of these lists is displayed in a new tabbed window opened by PatchDiff2.

The Identical Functions list contains the list of functions that PatchDiff2 deems to be identical in both databases. From an analysis point of view, these functions are likely to be uninteresting because they contribute nothing to the changes that produced the patched version of the binary.

The Unmatched Functions list shows functions from both databases that do not appear to be similar to one another according to the metrics applied by PatchDiff2. In practice, these functions have either been added to the patched version, removed from the unpatched version, or are too similar to other functions within the same binary to be able to distinguish them from corresponding functions in the second binary. With careful manual analysis it is often possible to match pairs of functions within the Unmatched Functions list. As a general rule of thumb, it is a good idea to manually compare the structure of functions that have similar numbers of signatures. To facilitate this, it is best to sort the list based on the sig column so that functions with similar numbers of signatures are listed near one another. The first few lines of an unmatched functions list sorted on sig are shown here.

File Function name Function address Sig Hash CRC ---- ------------- ---------------- --- ---- --- 1 sub_7CB25FE9 7CB25FE9 000000F0 F4E7267B 411C3DCC 1 sub_7CB6814C 7CB6814C 000000F0 F4E7267B 411C3DCC 2 sub_7CB6819A 7CB6819A 000000F0 F4E7267B 411C3DCC 2 sub_7CB2706A 7CB2706A 000000F0 F4E7267B 411C3DCC

It is clear that the two functions from file one are related to the two functions from file two; however, PatchDiff2 is unable to determine how to pair them up. It is not uncommon to see multiple functions with identical structures in binaries that make use of the C++ standard template library (STL). If you are able to manually match a function from one file to its corresponding function in the other file, you may use PatchDiff2’s Set Match feature (available on the context-sensitive menu) to choose one function in the list and match it to a second function in the list. Figure 22-1 shows the Set Match dialog.

Manual matching begins when you choose one function using the Set Match menu option. In the resulting dialog, you must enter the address of the matching function in the file you are not viewing. The Propagate option asks PatchDiff2 to match as many additional functions as it can, given that you have informed it of a new match.

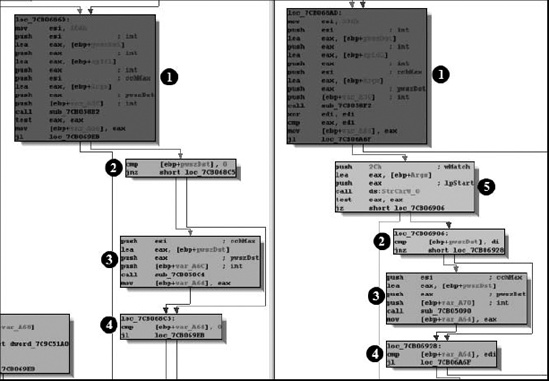

The Matched Functions list contains the list of functions that PatchDiff2 deems sufficiently similar, yet not quite identical, according to the metrics applied by in the matching process. Right-clicking any entry in this list and selecting Display Graphs causes PatchDiff2 to display flow graphs for the two matched functions. One such pair of graphs is shown in Figure 22-2. PatchDiff2 makes use of color coding to highlight blocks that have been introduced into the patched version of the binary, making it easy to focus on the changed portions of the code.

In these graphs, blocks  through

through  are present in both functions, while block

are present in both functions, while block  has been added in the patched version of the function. During differential analysis, matched functions may be of the highest interest initially because they are likely to contain the changes that have been incorporated into the patched binary that address vulnerabilities discovered in the original binary. Close study of these changes may reveal the corrections that have been made or safety checks that have been added in order to address incorrect behavior or exploitable conditions. If we fail to find any interesting changes highlighted in the Matched Functions list, then the Unmatched Functions list is our only other option for attempting to locate the patched code.

has been added in the patched version of the function. During differential analysis, matched functions may be of the highest interest initially because they are likely to contain the changes that have been incorporated into the patched binary that address vulnerabilities discovered in the original binary. Close study of these changes may reveal the corrections that have been made or safety checks that have been added in order to address incorrect behavior or exploitable conditions. If we fail to find any interesting changes highlighted in the Matched Functions list, then the Unmatched Functions list is our only other option for attempting to locate the patched code.

[190] See http://www.zynamics.com/bindiff.html. Note that in March 2011, Zynamics was acquired by Google.

[192] See http://corelabs.coresecurity.com/index.php?module=Wiki&action=view&type=tool&name=turbodiff.

[194] See http://code.google.com/p/patchdiff2. Note also that Alexander Pick has ported PatchDiff2 to IDA 6.0 for OS X. For more information please see https://github.com/alexander-pick/patchdiff2_ida6.