In Chapter 6, we discussed the most common calling conventions utilized in C and C++ code. While adherence to a published calling convention is crucial when attempting to interface one compiled module to another, nothing prohibits the use of custom calling conventions by functions within a single module. This is commonly seen in highly optimized functions that are not designed to be called from outside the module in which they reside.

The following code represents the first four lines of a function that uses a nonstandard calling convention:

.text:000158AC sub_158AC proc near .text:000158AC.text:000158AC arg_0 = dword ptr 4 .text:000158AC .text:000158AC push [esp+arg_0] .text:000158B0

mov edx, [eax+118h] .text:000158B6 push eax .text:000158B7

movzx ecx, cl .text:000158BA mov cl, [edx+ecx+0A0h]

According to IDA’s analysis, only one argument  exists in the function’s stack frame. However, upon closer inspection of the code, you can see that both the EAX register

exists in the function’s stack frame. However, upon closer inspection of the code, you can see that both the EAX register  and the CL register

and the CL register  are used without any initialization taking place within the function. The only possible conclusion is that both EAX and CL are expected to be initialized by the caller. Therefore, you should view this function as a three-argument function rather than a single-argument function, and you must take special care when calling it to ensure that the three arguments are all in their proper places.

are used without any initialization taking place within the function. The only possible conclusion is that both EAX and CL are expected to be initialized by the caller. Therefore, you should view this function as a three-argument function rather than a single-argument function, and you must take special care when calling it to ensure that the three arguments are all in their proper places.

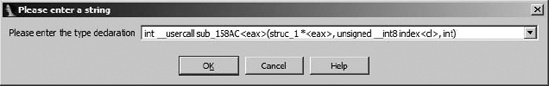

IDA allows you to specify custom calling conventions for any function by setting the function’s “type.” This is done by entering the function’s prototype via the Edit ▸ Functions ▸ Set function type menu option and using IDA’s __usercall calling convention. Figure 20-1 shows the resulting dialog used to set the type for sub_158AC in the preceding example.

For clarity, the declaration is shown again here:

int __usercall sub_158AC<eax>(struc_1 *<eax>, unsigned __int8 index<cl>, int)

Here the IDA keyword __usercall is used in place of one of the standard calling conventions such as __cdecl or __stdcall. The use of __usercall requires us to tell IDA the name of the register used to hold the function’s return value by appending the register name to the name of the function (yielding sub_158AC<eax> in this case). If the function returns no value, the return register may be omitted. Within the parameter list, each register-based parameter must also be annotated by appending the corresponding register name to the parameter’s data type. After the function’s type has been set, IDA propagates parameter information to calling functions, which results in improved commenting of function call sequences as shown in the following listing:

.text:00014B9Flea eax, [ebp+var_218] ; struc_1 * .text:00014BA5

mov cl, 1 ; index .text:00014BA7

push edx ; int .text:00014BA8 call sub_158AC

Here it is clear that IDA recognizes that EAX will hold the first argument to the function  , CL will hold the second argument

, CL will hold the second argument  , and the third argument will placed on the stack

, and the third argument will placed on the stack  .

.

To demonstrate that calling conventions can vary widely even with a single executable, a second example using a custom calling convention is taken from the same binary file and shown here:

.text:0001669E sub_1669E proc near .text:0001669E.text:0001669E arg_0 = byte ptr 4 .text:0001669E .text:0001669E

mov eax, [esi+18h] .text:000166A1 add eax, 684h .text:000166A6 cmp [esp+arg_0], 0

Here again, IDA has indicated that the function accesses only one argument  within the stack frame. Closer inspection makes it quite clear that the ESI register

within the stack frame. Closer inspection makes it quite clear that the ESI register  is also expected to be initialized prior to calling this function. This example demonstrates that even with the same binary file, the registers chosen to hold register-based arguments may vary from function to function.

is also expected to be initialized prior to calling this function. This example demonstrates that even with the same binary file, the registers chosen to hold register-based arguments may vary from function to function.

The lesson to be learned here is to make certain that you understand how each register used in a function is initialized. If a function makes use of a register prior to initializing that register, then the register is being used to pass a parameter. Please refer to Chapter 6 for a review of which registers are used by various compilers and common calling conventions.