By now it should be clear that a high-quality disassembly is much more than a list of mnemonics and operands derived from a sequence of bytes. In order to make a disassembly useful, it is important to augment the disassembly with information derived from the processing of various API-related data such as function prototypes and standard datatypes. In Chapter 8 we discussed IDA’s handling of data structures, including how to access standard API data structures and how to define your own custom data structures. In this chapter, we continue our discussion of extending IDA’s knowledge by examining the use of IDA’s idsutils and loadint utilities. These utilities are available on your IDA distribution CD or via download at the Hex-Rays download site.[87]

IDA derives its knowledge of functions from two sources: type library (.til) files and IDS utilities (.ids) files. During the initial analysis phase, IDA uses information stored in these files to both improve the accuracy of the disassembly and make the disassembly more readable. It does so by incorporating function parameter names and types as well as comments that have been associated with various library functions.

In Chapter 8 we discussed type library files as the mechanism by which IDA stores the layout of complex data structures. Type library files are also the means by which IDA records information about a function’s calling conventions and parameter sequence. IDA uses function signature information in several ways. First, when a binary uses shared libraries, IDA has no way to know what calling conventions may be employed by the functions in those libraries. In such cases, IDA attempts to match library functions against their associated signatures in a type library file. If a matching signature is found, IDA can understand the calling convention used by the function and make adjustments to the stack pointer as necessary (recall that stdcall functions perform their own stack cleanup). The second use for function signatures is to annotate the parameters being passed to a function with comments that denote exactly which parameter is being pushed on the stack prior to calling the function. The amount of information present in the comment depends on how much information was present in the function signature that IDA was able to parse. The two signatures that follow are both legal C declarations, though the second provides more insight into the function, as it provides formal parameter names in addition to datatypes.

LSTATUS _stdcall RegOpenKey(HKEY, LPCTSTR, PHKEY); LSTATUS _stdcall RegOpenKey(HKEY hKey, LPCTSTR lpSubKey, PHKEY phkResult);

IDA’s type libraries contain signature information for a large number of common API functions, including a substantial portion of the Windows API. A default disassembly of a call to the RegOpenKey function is shown here:

.text:00401006 00C lea eax, [ebp+hKey] .text:00401009 00C push eax

; phkResult .text:0040100A 010 push offset

SubKey ; "Software\\Hex-Rays\\IDA" .text:0040100F 014 push 80000001h

; hKey .text:00401014 018 call ds:RegOpenKeyA .text:0040101A

00C mov [ebp+var_8], eax

Note that IDA has added comments in the right margin  , indicating which parameter is being pushed at each instruction leading up to the call to

, indicating which parameter is being pushed at each instruction leading up to the call to RegOpenKey. When formal parameter names are available in the function signature, IDA attempts to go one step further and automatically name variables that correspond to specific parameters. In two cases in the preceding example  , we can see that IDA has named a local variable (

, we can see that IDA has named a local variable (hKey) and a global variable (SubKey) based on their correspondence with formal parameters in the RegOpenKey prototype. If the parsed function prototype had contained only type information and no formal parameter names, then the comments in the preceding example would name the datatypes of the corresponding arguments rather than the parameter names. In the case of the lpSubKey parameter, the parameter name is not displayed as a comment because the parameter happens to point to a global string variable, and the content of the string is being displayed using IDA’s repeating comment facility. Finally, note that IDA has recognized RegOpenKey as a stdcall function and automatically adjusted the stack pointer  as

as RegOpenKey would do upon returning. All of this information is extracted from the function’s signature, which IDA also displays as a comment within the disassembly at the appropriate import table location, as shown in the following listing:

.idata:0040A000 ; LSTATUS __stdcall RegOpenKeyA(HKEY hKey, LPCSTR lpSubKey, PHKEY phkResult) .idata:0040A000 extrn RegOpenKeyA:dword ; CODE XREF: _main+14p .idata:0040A000 ; DATA XREF: _main+14r

The comment displaying the function prototype comes from an IDA .til file containing information on Windows API functions.

Under what circumstances might you wish to generate your own function type signatures?[88] Whenever you encounter a binary that is linked, either dynamically or statically, to a library for which IDA has no function prototype information, you may want to generate type signature information for all of the functions contained in that library in order to provide IDA with the ability to automatically annotate your disassembly. Examples of such libraries might include common graphics or encryption libraries that are not part of a standard Windows distribution but that might be in widespread use. The OpenSSL cryptographic library is one example of such a library.

Just as we were able to add complex datatype information to a database’s local .til file in Chapter 8, we can add function prototype information to that same .til file by having IDA parse one or more function prototypes via File ▸ Load File▸ Parse C Header File. Similarly, you may use tilib.exe (see Chapter 8) to parse header files and create standalone .til files, which can be made globally available by copying them into <IDADIR>/til.

This is all well and good when you happen to have access to source code that you then allow IDA (or tilib.exe)to parse on your behalf. Unfortunately, more often than you would like, you will have no access to source code, yet you will want the same high-quality disassembly. How can you go about educating IDA if you have no source code for it to consume? This is the precisely the purpose of the IDS utilities, or idsutils. The IDS utilities are a set of three utility programs used to create .ids files. We first discuss what a .ids file is and then turn our attention to creating our own .ids files.

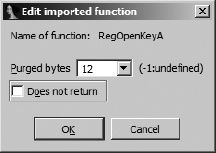

IDA uses .ids files to supplement its knowledge of library functions. A .ids file describes the content of a shared library by listing every exported function contained within the library. Information detailed for each function includes the function’s name, its associated ordinal number,[90] whether the function utilizes stdcall, and if so, how many bytes the function clears from the stack upon return, and optional comments to be displayed when the function is referenced within a disassembly. In practice, .ids files are actually compressed .idt files, with .idt files containing the textual descriptions of each library function.

When an executable file is first loaded into a database, IDA determines which shared library files the executable depends on. For each shared library, IDA searches for a corresponding .ids file in the <IDADIR>/ids hierarchy in order to obtain descriptions of any library functions that the executable may reference. It is important to understand that .ids files do not necessarily contain function signature information. Therefore, IDA may not provide function parameter analysis based on information contained solely in .ids files. IDA can, however, perform accurate stack pointer accounting when a .ids file contains correct information concerning the calling conventions employed by functions and the number of bytes that the functions clear from the stack. In situations where a DLL exports mangled names, IDA may be able to infer a function’s parameter signature from the mangled name, in which case this information becomes available when the .ids file is loaded. We describe the syntax of .idt files in the next section. In this regard, .til files contain more useful information with respect to disassembling function calls, though source code is required in order to generate .til files.

IDA’s idsutils utilities are used to create .ids files. The utilities include two library parsers, dll2idt for extracting information from Windows DLLs and ar2idt for extracting information from ar-style libraries. In both cases, the output is a text .idt file containing a single line per exported function that maps the exported function’s ordinal number to the function’s name. The syntax for .idt files, which is very straightforward, is described in the readme.txt file included with idsutils. The majority of lines in a .idt file are used to describe exported functions according to the following scheme:

An export entry begins with a positive number. This number represents the ordinal number of the exported function.

The ordinal number is followed by a space and then a

Namedirective in the formName=function, for example,Name=RegOpenKeyA. If the special ordinal value zero is used, then theNamedirective is used to specify the name of the library described in the current .idt file, such as in this example:0 Name=advapi32.dll

An optional

Pascaldirective may be used to specify that a function uses thestdcallcalling convention and to indicate how many bytes the function removes from the stack upon return. Here is an example:483 Name=RegOpenKeyA Pascal=12

An optional

Commentdirective can be appended to an export entry to specify a comment to be displayed with the function at each reference to the function within a disassembly. A completed export entry might look like the following:483 Name=RegOpenKeyA Pascal=12 Comment=Open a registry key

Additional, optional directives are described in the idsutils readme.txt file. The purpose of the idsutils parsing utilities is to automate, as much as possible, the creation of .idt files. The first step in creating a .idt file is to obtain a copy of the library that you wish to parse; the next step is to parse it using the appropriate parsing utility. If we wished to create a .idt file for the OpenSSL -related library ssleay32.dll, we would use the following command:

$ ./dll2idt.exe ssleay32.dll

Convert DLL to IDT file. Copyright 1997 by Yury Haron. Version 1.5

File: ssleay32.dll ... okSuccessful parsing in this case results in a file named SSLEAY32.idt. The difference in capitalization between the input filename and the output filename is due to the fact that dll2idt derives the name of the output file based on information contained within the DLL itself. The first few lines of the resulting .idt file are shown here:

ALIGNMENT 4 ;DECLARATION ; 0 Name=SSLEAY32.dll ; 121 Name=BIO_f_ssl 173 Name=BIO_new_buffer_ssl_connect 122 Name=BIO_new_ssl 174 Name=BIO_new_ssl_connect 124 Name=BIO_ssl_copy_session_id

Note that it is not possible for the parsers to determine whether a function uses stdcall and, if so, how many bytes are purged from the stack. The addition of any Pascal or Comment directives must be performed manually using a text editor prior to creating the final .ids file. The final steps for creating a .ids are to use the zipids utility to compress the .idt file and then to copy the resulting .ids file to <IDADIR>/ids.

$ ./zipids.exe SSLEAY32.idt

File: SSLEAY32.idt ... {219 entries [0/0/0]} packed

$ cp SSLEAY32.ids ../Ida/idsAt this point, IDA loads SSLEAY32.ids anytime a binary that links to ssleay32.dll is loaded. If you elect not to copy your newly created .ids files into <IDADIR>/ids, you can load them at any time via File ▸ Load File ▸ IDS File.

An additional step in the use of .ids files allows you to link .ids files to specific .sig or .til files. When you choose .ids files, IDA utilizes an IDS configuration file named <IDADIR>/ida/idsnames. This text file contains lines to allow for the following:

Map a shared library name to its corresponding .ids filename. This allows IDA to locate the correct .ids file when a shared library name does not translate neatly to an MS-DOS-style 8.3 filename as with the following:

libc.so.6 libc.ids +

Map a .ids file to a .til file. In such cases, IDA automatically loads the specified .til file whenever it loads the specified .ids file. The following example would cause openssl.til to be loaded anytime SSLEAY32.ids is loaded (see

idsnamesfor syntax details):SSLEAY32.ids SSLEAY32.ids + openssl.til

Map a .sig file to a corresponding .ids file. In this case, IDA loads the indicated .ids file anytime the named .sig file is applied to a disassembly. The following line directs IDA to load SSLEAY32.ids anytime a user applies the libssl.sig FLIRT signature:

libssl.sig SSLEAY32.ids +

In Chapter 15 we will look at a script-oriented alternative to the library parsers provided by idsutils, and we’ll leverage IDA’s function-analysis capabilities to generate more descriptive .idt files.

[87] See http://www.hex-rays.com/idapro/idadown.htm. A valid IDA username and password are required.

[88] In this case we are using the term signature to refer to a function’s parameter type(s), quantity, and sequence rather than a pattern of code to match the compiled function.

[89] Use of the simplex method as introduced in IDA version 5.1 is described in a blog post by Ilfak here: http://www.hexblog.com/2006/06/.

[90] An ordinal number is an integer index associated with each exported function. The use of ordinals allows a function to be located using an integer lookup table rather than by a slower string comparison against the function’s name.