With some disassembly background under our belts, and before we begin our dive into the specifics of IDA Pro, it will be useful to understand some of the other tools that are used for reverse engineering binaries. Many of these tools predate IDA and continue to be useful for quick glimpses into files as well as for double-checking the work that IDA does. As we will see, IDA rolls many of the capabilities of these tools into its user interface to provide a single, integrated environment for reverse engineering. Finally, although IDA does contain an integrated debugger, we will not cover debuggers here as Chapter 24, Chapter 25, and Chapter 26 are dedicated to the topic.

When first confronted with an unknown file, it is often useful to answer simple questions such as “What is this thing?” The first rule of thumb when attempting to answer that question is to never rely on a filename extension to determine what a file actually is. That is also the second, third, and fourth rules of thumb. Once you have become an adherent of the file extensions are meaningless line of thinking, you may wish to familiarize yourself with one or more of the following utilities.

The file command is a standard utility, included with most *NIX-style operating systems and with the Cygwin[4] or MinGW[5] tools for Windows. File attempts to identify a file’s type by examining specific fields within the file. In some cases file recognizes common strings such as #!/bin/sh (a shell script) or <html> (an HTML document). Files containing non-ASCII content present somewhat more of a challenge. In such cases, file attempts to determine whether the content appears to be structured according to a known file format. In many cases it searches for specific tag values (often referred to as magic numbers[6]) known to be unique to specific file types. The hex listings below show several examples of magic numbers used to identify some common file types.

Windows PE executable file 000000004D 5A90 00 03 00 00 00 04 00 00 00 FF FF 00 00MZ.............. 00000010 B8 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 40 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ........@....... Jpeg image file 00000000FF D8FF E0 00 104A 46 49 4600 01 01 01 00 60 ......JFIF.....` 00000010 00 60 00 00 FF DB 00 43 00 0A 07 07 08 07 06 0A .`.....C........ Java .class file 00000000CA FE BA BE00 00 00 32 00 98 0A 00 2E 00 3E 08 .......2......>. 00000010 00 3F 09 00 40 00 41 08 00 42 0A 00 43 00 44 0A .?..@.A..B..C.D.

file has the capability to identify a large number of file formats, including several types of ASCII text files and various executable and data file formats. The magic number checks performed by file are governed by rules contained in a magic file. The default magic file varies by operating system, but common locations include /usr/share/file/magic, /usr/share/misc/magic, and /etc/magic. Please refer to the documentation for file for more information concerning magic files.

In some cases, file can distinguish variations within a given file type. The following listing demonstrates file’s ability to identify not only several variations of ELF binaries but also information pertaining to how the binary was linked (statically or dynamically) and whether the binary was stripped or not.

idabook# file ch2_ex_*

ch2_ex.exe: MS-DOS executable PE for MS Windows (console)

Intel 80386 32-bit

ch2_ex_upx.exe: MS-DOS executable PE for MS Windows (console)

Intel 80386 32-bit, UPX compressed

ch2_ex_freebsd: ELF 32-bit LSB executable, Intel 80386,

version 1 (FreeBSD), for FreeBSD 5.4,

dynamically linked (uses shared libs),

FreeBSD-style, not stripped

ch2_ex_freebsd_static: ELF 32-bit LSB executable, Intel 80386,

version 1 (FreeBSD), for FreeBSD 5.4,

statically linked, FreeBSD-style, not stripped

ch2_ex_freebsd_static_strip: ELF 32-bit LSB executable, Intel 80386,

version 1 (FreeBSD), for FreeBSD 5.4,

statically linked, FreeBSD-style, stripped

ch2_ex_linux: ELF 32-bit LSB executable, Intel 80386,

version 1 (SYSV), for GNU/Linux 2.6.9,

dynamically linked (uses shared libs),

not stripped

ch2_ex_linux_static: ELF 32-bit LSB executable, Intel 80386,

version 1 (SYSV), for GNU/Linux 2.6.9,

statically linked, not stripped

ch2_ex_linux_static_strip: ELF 32-bit LSB executable, Intel 80386,

version 1 (SYSV), for GNU/Linux 2.6.9,

statically linked, stripped

ch2_ex_linux_stripped: ELF 32-bit LSB executable, Intel 80386,

version 1 (SYSV), for GNU/Linux 2.6.9,

dynamically linked (uses shared libs), strippedfile and similar utilities are not foolproof. It is quite possible for a file to be misidentified simply because it happens to bear the identifying marks of some file format. You can see this for yourself by using a hex editor to modify the first four bytes of any file to the Java magic number sequence: CA FE BA BE. The file utility will incorrectly identify the newly modified file as compiled Java class data. Similarly, a text file containing only the two characters MZ will be identified as an MS-DOS executable. A good approach to take in any reverse engineering effort is to never fully trust the output of any tool until you have correlated that output with several tools and manual analysis.

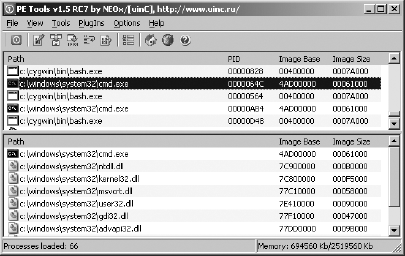

PE Tools[7] is a collection of tools useful for analyzing both running processes and executable files on Windows systems. Figure 2-1 shows the primary interface offered by PE Tools, which displays a list of active processes and provides access to all of the PE Tools utilities.

From the process list, users can dump a process’s memory image to a file or utilize the PE Sniffer utility to determine what compiler was used to build the executable or whether the executable was processed by any known obfuscation utilities. The Tools menu offers similar options for analysis of disk files. Users can view a file’s PE header fields by using the embedded PE Editor utility, which also allows for easy modification of any header values. Modification of PE headers is often required when attempting to reconstruct a valid PE from an obfuscated version of that file.

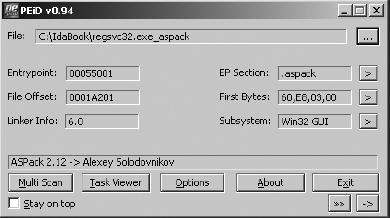

PEiD[8] is another Windows tool whose primary purposes are to identify the compiler used to build a particular Windows PE binary and to identify any tools used to obfuscate a Windows PE binary. Figure 2-2 shows the use of PEiD to identify the tool (ASPack in this case) used to obfuscate a variant of the Gaobot[9] worm.

Many additional capabilities of PEiD overlap those of PE Tools, including the ability to summarize PE file headers, collect information on running processes, and perform basic disassembly.

[4] See http://www.cygwin.com/.

[5] See http://www.mingw.org/.

[6] A magic number is a special tag value required by some file format specifications whose presence indicates conformance to such specifications. In some cases humorous reasons surround the selection of magic numbers. The MZ tag in MS-DOS executable file headers represents the initials of Mark Zbikowski, one of the original architects of MS-DOS, while the hex value 0xcafebabe, the well-known magic number associated with Java .class files, was chosen because it is an easily remembered sequence of hex digits.

[8] See http://peid.info/.