If you have an Android device, you can debug your web applications using the ADB Chrome extension and the Chrome DevTools introduced in Chapter 2, Key Concepts in OpenLayers. There are quite a few steps to get it all working, but it's worth it when you need it! So, here goes:

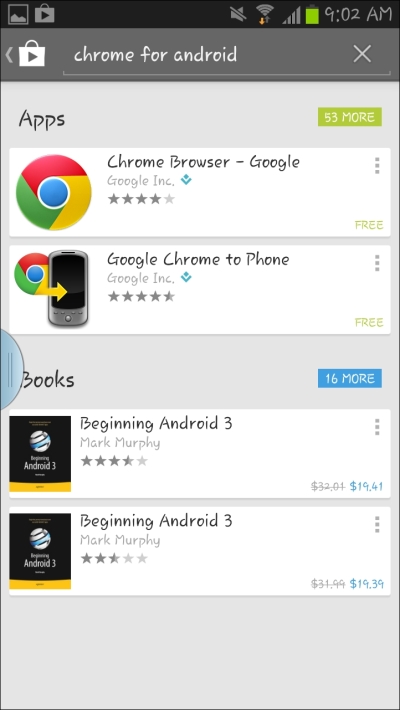

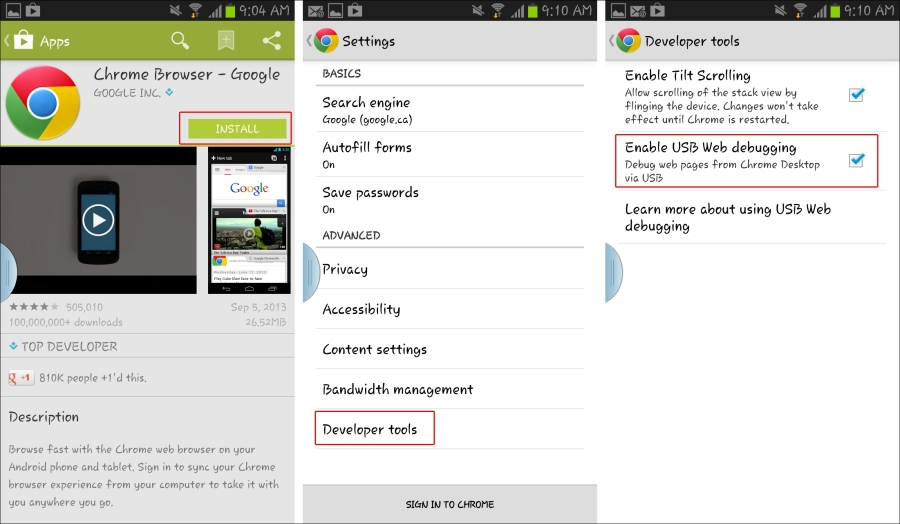

- If Chrome is not already installed by default, install Chrome for Android version 28 or later from Google Play, and connect your device to your computer with a USB. Here's how your screen looks when you perform these actions:

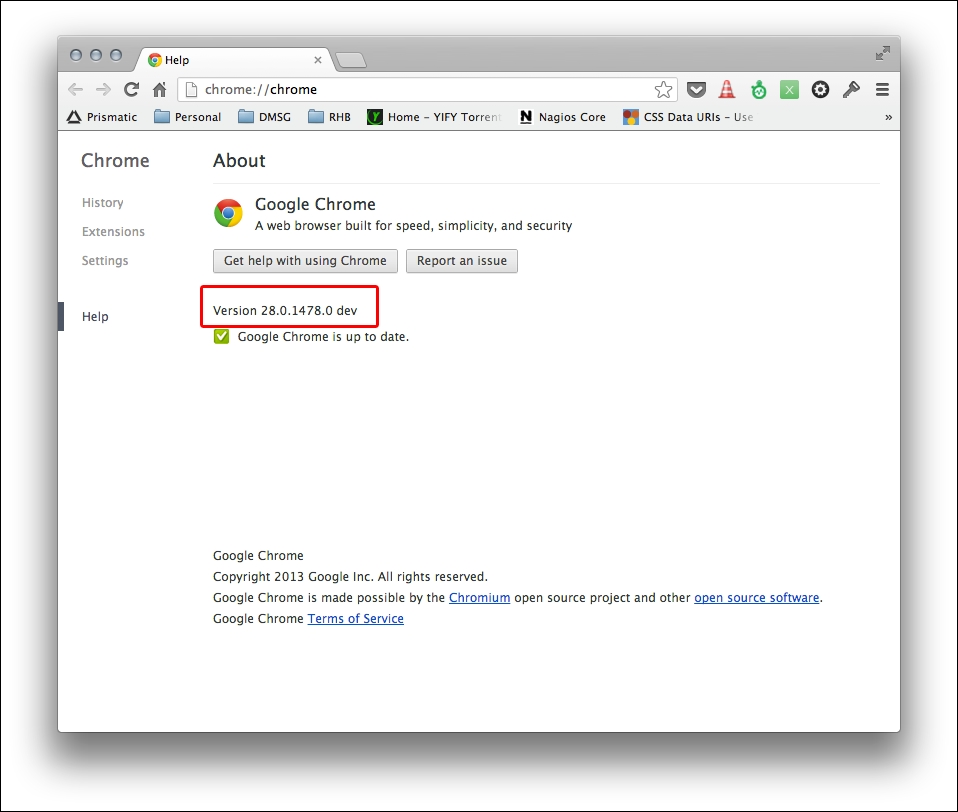

- Install Chrome version 28 or later on your development machine. The following screenshot depicts the screen as it should look while performing this action:

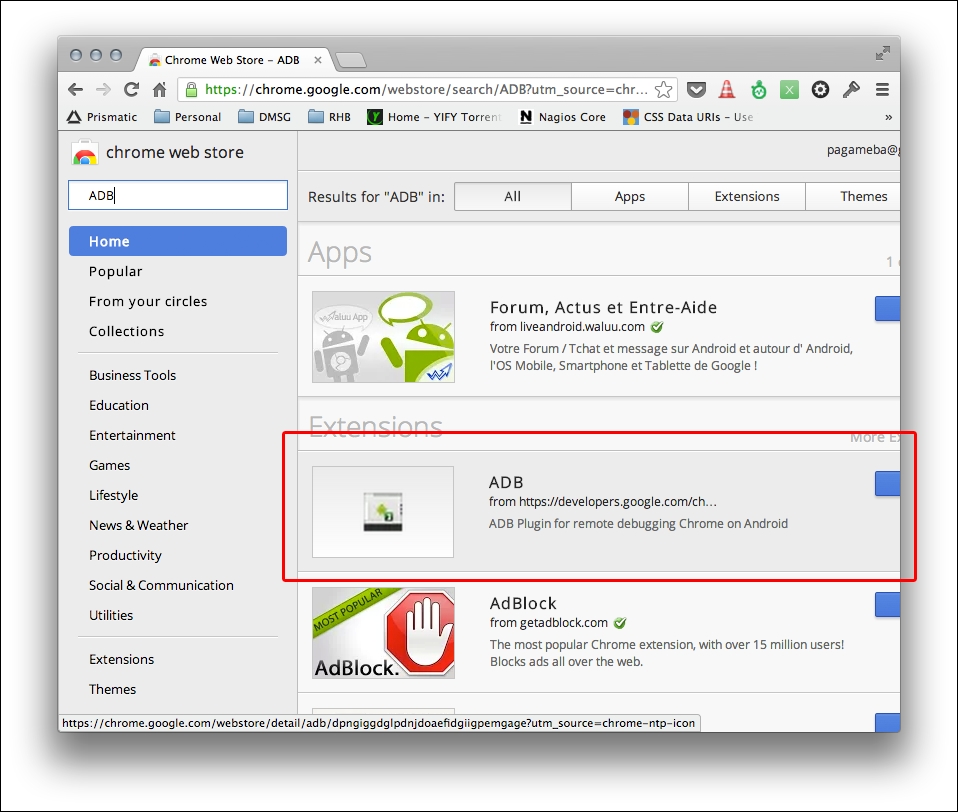

- Install ADB Chrome Extension available in the Chrome web store by opening a new tab in Chrome, clicking the App Store icon, and then searching for ADB, as shown in the following screenshot:

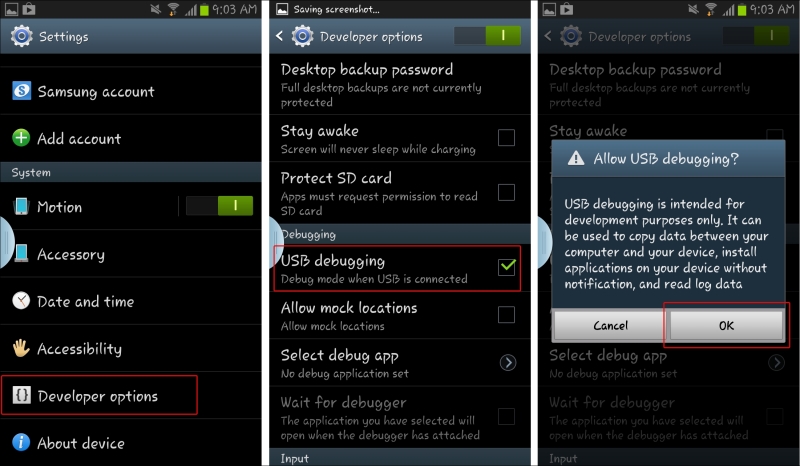

- Enable USB debugging on your device by opening the Developer options settings panel and clicking the checkbox for USB debugging, as follows:

- For Android 3.2 and older, go to Settings | Applications | Development.

- For Android 4.0 and newer, go to Settings | Developer.

- For Android 4.2 and newer, the Developer options panel is hidden by default. To make it available, go to Settings | About phone and tap Build number seven times. Return to the previous screen to find Developer options. Here's how the Developer options screens look during this process:

- Connect your Android device to your computer with a USB cable.

- Launch Chrome for Android on your device, open Settings | Advanced | Developer Tools, and check off the Enable USB Web debugging option, as shown in the following screenshots:

- When you first connect your Android device to your computer, you might see an alert requesting permission to Allow USB debugging. To avoid seeing this again, check Always allow from this computer, and click on OK.

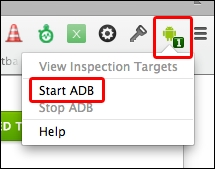

- Start debugging in Chrome on your computer with ADB Chrome Extension by clicking on the ADB icon in the Chrome toolbar and selecting Start ADB, as follows:

- Click on View Inspection Targets to open the about:inspect page that displays each connected device and its tabs.

- Find the mobile device tab you want to debug, and click on the inspect link next to its URL.

Phew! First, we made sure that we installed Chrome for Android on the device and the latest version of Chrome on our computer. Next, we installed ADB Chrome Extension for Chrome. Then, we allowed USB debugging on the device. Finally, we launched ADB Chrome Extension to see it in action. You can now debug your mobile web application running on your device with the Chrome Developer Tools.

Note

It is also possible to debug using Firefox on Android; see https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Tools/Remote_Debugging/Firefox_for_Android for more information.

Native debugging on mobile is great once you get it working, but what do you do when you don't have a USB cable with you, you have an iPhone but not a Mac, or you want to debug on some other device? There's a solution, of course, and the solution is to use WEINRE (WEb INspector REmote), an open source package that gives you an almost native debugging capability for mobile devices.

WEINRE is part of the Apache Cordova project (http://cordova.apache.org/) and was pioneered by Patrick Mueller. We will talk about Apache Cordova in the next section.

Using WEINRE involves combining three separate components, as follows:

- The debug server: This is an HTTP server provided by WEINRE; it's used by the debug client and the debug target.

- The debug client: This is the Web Inspector user interface we will use to debug your application. It displays the Elements and Console panels, among other things.

- The debug target: This refers to both the machine running the browser that we want to debug and the web page being debugged.

The debug client and the debug server run on our development computer and the debug target runs on the mobile device.

To activate the debug target, we will need to add some JavaScript code, provided by the debug server, into the web page.

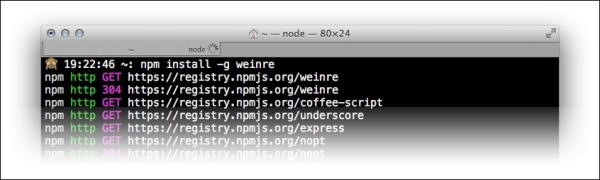

WEINRE is a Node.js application and is published as an NPM package. We've already talked about using Node.js and NPM to run a small server for editing features in Chapter 8, Interacting with Your Map. To install WEINRE then, all we need to do is open a command prompt and run the following command:

npm install –g weinre

This is how the command prompt would look when we run the preceding command. This command instructs NPM to install the WEINRE package globally, which will make the weinre command available to you.

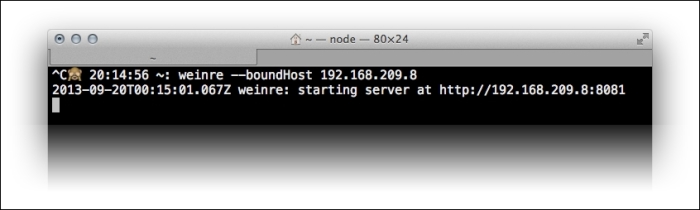

To start WEINRE, we need to use the IP address of the development machine—see the beginning of this chapter if you don't remember it. Open a command prompt and run the following command:

weinre –boundHost <your ip address>

This is how the command prompt would look when we run the preceding command. The boundHost option allows the debug target's JavaScript to be loaded in a page on another machine, such as our mobile device. There are several other command-line options that you can supply to the weinre command; for the most part, you don't need them, but you can read about them in the WEINRE documentation at http://people.apache.org/~pmuellr/weinre/docs/latest/Running.html.

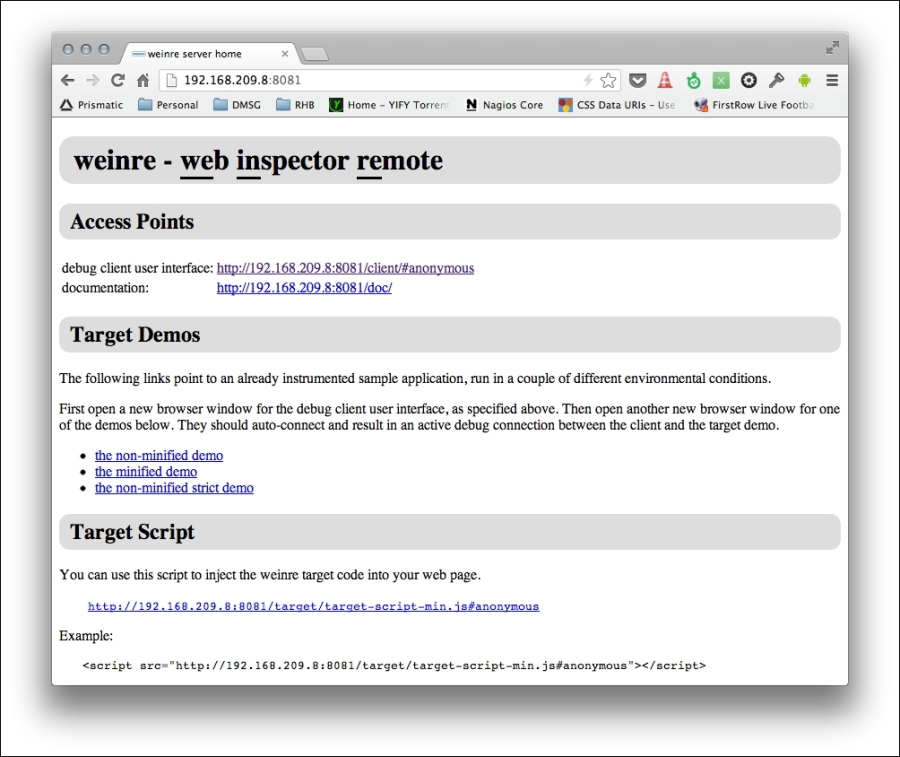

WEINRE starts a debug server and reports the URL at which the debug server page can be accessed. Copy this URL and open it in a web browser. The following is how the page will look when these actions have been performed:

This page has the information and links we need to get started with debugging our mobile web application. The first section, Access Points, contains links to the debug client user interface and documentation. The second section, Target Demos, gives you some quick links to try out WEINRE debugging right away. Try them if you like. The third section contains the link to the JavaScript we will need to add to our mobile web page to activate the debug target code. Let's go ahead with this now.

Open the mobile example page in a code editor. Copy the <script> tag from the following example in the target script section, and paste it into the example page just after the <title> tag, as follows:

<title>Mobile Examples</title> <script src="http://192.168.209.8:8081/target/target-script-min.js#anonymous"></script>

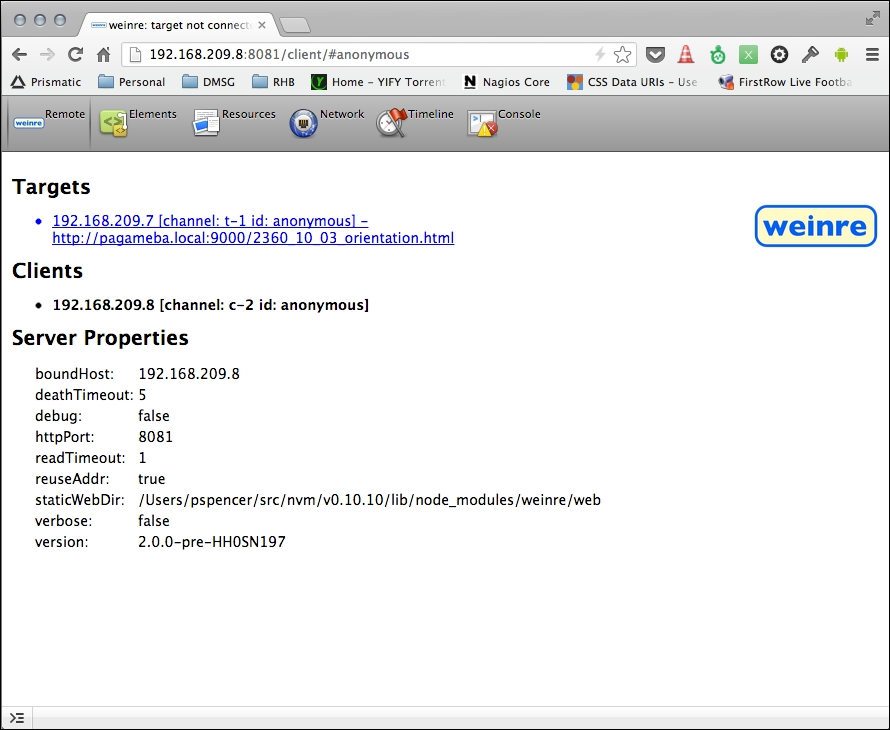

Now, for the big finale—load the mobile example on your mobile device, and then click on the link to open the debug client on your desktop machine. After that, this is how your screen will look:

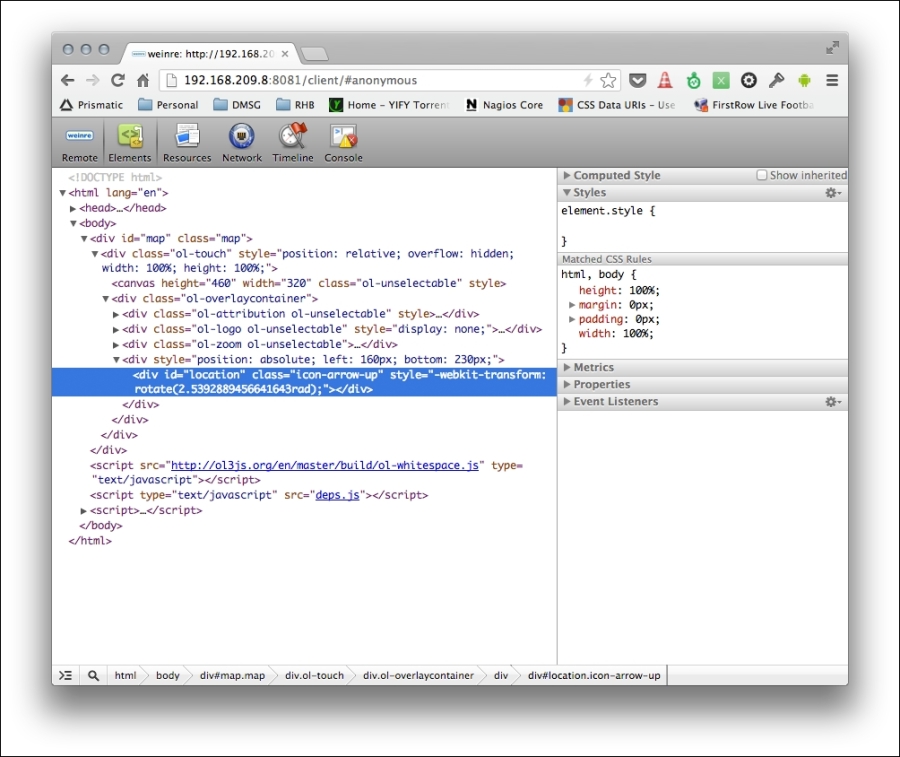

The Remote tab shows the debug target connected and some other information. You can now click on the Elements, Resources, Network, Timeline, and Console tab. Click on the Elements tab to show the Elements panel. This is how your screen will look after performing these actions:

You can use the Elements panel just like Chrome Developer Tools and explore the DOM. Note that it can take a few moments for WEINRE to respond with information, so be patient and wait for it to appear.

The Resources panel shows WebSQL databases and data stored in the local storage and session storage. The Network panel shows XML HTTP requests issued after the page has loaded. Unlike Chrome Developer Tools, it can't capture the assets loaded by the page itself.

The Timeline panel can be used to display timing information about events and to track user-triggered events. Using this panel is beyond the scope of this book, but if you are interested, then check out the WEINRE documentation.

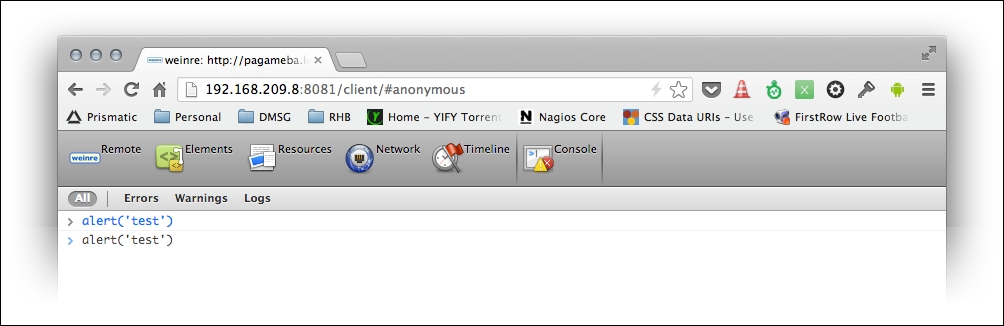

The last tab, Console, displays the JavaScript log and provides a command line for executing arbitrary JavaScript in your web page. Try typing the following command into the console and hit Enter:

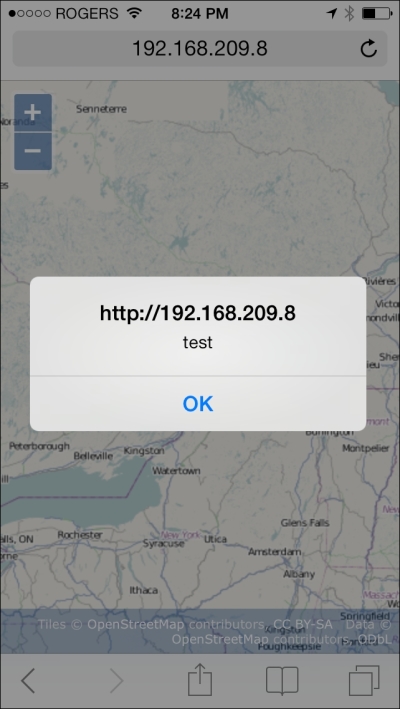

alert('test');

Your screen will look like this when the preceding command has been entered.

You should see an alert pop up on your mobile device, as shown in the following screenshot:

The Console tab also shows log messages, and we can filter by message types (Errors, Warnings, and Logs). Some log messages are generated by the browser itself, typically when an error happens, and we can use WEINRE to see if errors are happening. We can also programmatically send messages to log in our code using methods of the global console object that are available in all web browsers.

WEINRE isn't as complete as native debugging with iOS and Android, but it can certainly help out at a pinch.