Let's walk through creating a simple map from the beginning. Create a new file in your text editor to get started. To make it easy, save this file in the sandbox

folder. Remember that all the samples are set up to use the version of OpenLayers we've provided in the assets folder:

- Start with the HTML code needed to set up the page:

<!doctype html> <html> <head> <title> Map Examples </title> <link rel="stylesheet" href="../assets/ol3/ol.css" type="text/css" /> <link rel="stylesheet" href="../assets/css/samples.css" type="text/css" /> </head> <body> <div id="map" class="map"></div> <script src="../assets/ol3/ol.js"> </script>We are just setting up a standard HTML 5 web page and including our stylesheets and the OpenLayers library.

- Add a

<script>block with the following code:<script> var layer = new ol.layer.Tile({ source: new ol.source.OSM() }); var london = ol.proj.transform([-0.12755, 51.507222], 'EPSG:4326', 'EPSG:3857'); var view = new ol.View({ center: london, zoom: 6, }); var map = new ol.Map({ target: 'map', layers: [layer], view: view }); </script>This code should look familiar to the ones used in the previous chapters, and you'll be seeing it (with minor variations) quite a bit through the rest of this book. We create a layer that will show OSM tiles, use

londonas our starting point for the view and create an instance ofol.Mapin ourmapdiv. - Finish off by closing the body and HTML tags:

</body> </html>

- Save this file as

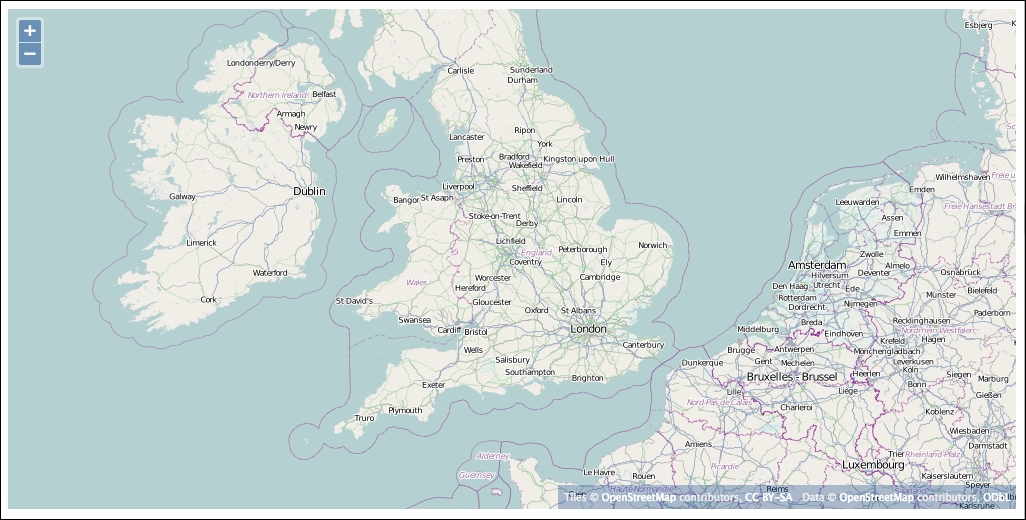

map.htmland open it in your web browser, you should see a familiar sight, as shown here:

Let's look a little closer at how we create our map object in this block of code:

var map = new ol.Map({

target: 'map',

layers: [layer],

view: view

});We use the new operator to create an instance of the ol.Map class and pass it an object literal containing several options, namely, target, view, and layers. We've used these before in the previous examples without really explaining them or any of the other options we might want to use. Here's the full list of available options and what they do:

|

Name |

Type |

Description |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Controls are covered in detail in Chapter 7, Wrapping Our Heads Around Projections; so, we don't need to go in-depth here. We can define our map's controls when we create the map object by specifying them with this option, or we can add them via the |

|

|

|

The

|

|

|

|

Interactions are used by the map to handle browser events, such as the user clicking or dragging on the map. The map passes browser events to each of its interactions in sequence, allowing each to determine whether it should take action and whether it should consume (stop further processing of) the event. The order of interactions is important—if an interaction consumes a browser event, subsequent interactions will not see the event. Interactions are closely related to controls and are discussed in more detail in Chapter 8, Interacting with Your Map with controls. The default interactions, if this option is not provided, are |

|

|

|

This option indicates which HTML element will be used to receive keyboard events for interactions that use them (such as |

|

|

|

The |

|

|

|

This controls the display of the ol3 logo in the map, |

|

|

|

The overlays option defines which overlays will be added to the map initially. We will review them thoroughly in Chapter 8, Interacting with Your Map. |

|

|

|

The number of physical pixels per screen pixel, normally computed automatically. |

|

|

|

The

We'll discuss what these actually mean a little further on in this chapter. |

|

|

|

The target identifies the HTML element in which the map will be drawn on the web page. In all our examples, we pass a string value that matches the |

|

|

|

The |