Copyright © 2015 Packt Publishing

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles or reviews.

Every effort has been made in the preparation of this book to ensure the accuracy of the information presented. However, the information contained in this book is sold without warranty, either express or implied. Neither the authors, nor Packt Publishing, and its dealers and distributors will be held liable for any damages caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by this book.

Packt Publishing has endeavored to provide trademark information about all of the companies and products mentioned in this book by the appropriate use of capitals. However, Packt Publishing cannot guarantee the accuracy of this information.

First published: March 2011

Second published: January 2015

Production reference: 1210115

Published by Packt Publishing Ltd.

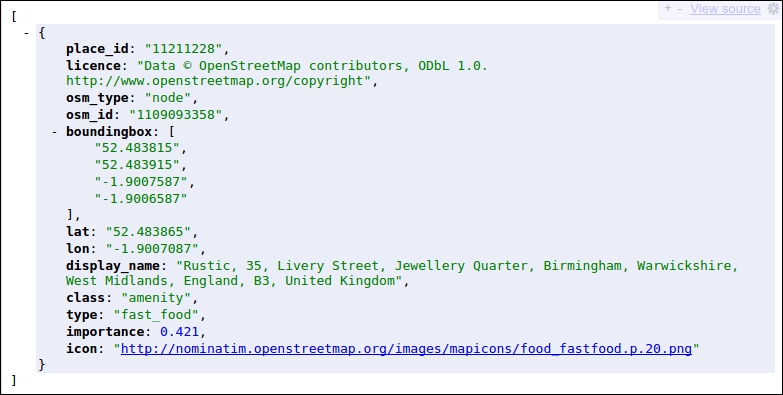

Livery Place

35 Livery Street

Birmingham B3 2PB, UK.

ISBN 978-1-78216-236-0

Authors

Thomas Gratier

Paul Spencer

Erik Hazzard

Reviewers

Jorge Arévalo

Gagan Bansal

Christopher Jennison

Arnaud Vandecasteele

Commissioning Editor

Usha Iyer

Acquisition Editors

Usha Iyer

Sam Wood

Content Development Editor

Sweny Sukumaran

Technical Editor

Parag Topre

Copy Editors

Sarang Chari

Janbal Dharmaraj

Neha Karnani

Project Coordinator

Rashi Khivansara

Proofreaders

Ting Baker

Paul Hindle

Linda Morris

Indexer

Mariammal Chettiyar

Graphics

Valentina D'silva

Disha Haria

Abhinash Sahu

Production Coordinator

Nilesh R. Mohite

Cover Work

Nilesh R. Mohite

Thomas Gratier is a GIS consultant living in Nantes, France, who mainly specializes in web development. He has an MSc degree in geography and urban planning from The Institute Of Alpine Geography of The University of Grenoble. Career-wise, he decided to steer towards more technical work but kept his geospatial passion in mind. He's gained 8 years of geospatial and programming experience, working for public authorities on water and flood risk prevention and management, various private urban consultancies in urban planning and web mapping solutions, and, multinational company CapGemini's GIS Division. He's continued building a stronger knowledge in IT technologies, open source and open data, and both web and geo standards. He does his development work with JavaScript, Pythons and PHP. His favorite libraries and tools for working are GDAL/OGR, PostGIS, QGIS, and OpenLayers, but he also enjoys using OpenStreetMap-related libraries, such as Mapnik or Osm2pgsql. He is an open source advocate, a Charter Member of The Open Source Geospatial Foundation (http://www.osgeo.org)(OSGeo). He gets involved in writing French translations for open source geospatial projects, such as MapServer and Zoo Project. With like-minded professionals, he contributes to weekly geospatial news updates at Geotribu (http://geotribu.net). He currently works as a freelance GIS consultant, providing development, consulting, and training services. More information can be found on his website at Web Geo Data Vore (http://webgeodatavore.com).

Paul Spencer is a software engineer who has worked in the field of open source geospatial software for more than 15 years. He is a strong advocate of open source development and champions its use whenever possible. Paul has architected several successful open source projects and been actively involved in many more. Paul was involved in the early design and development of OpenLayers and continues to be involved as the project evolves. Paul joined DM Solutions Group (DMSG) in 1998, bringing with him advanced software development skills and a strong understanding of the software-development process. In his time with the company, Paul has taken on a leadership role as the CTO and primary architect for DM Solutions Group's web mapping technologies and commercial solutions. Prior to joining DMSG, Paul worked for the Canadian Military, after achieving his master's degree in software engineering from The Royal Military College of Canada.

Erik Hazzard is the author of OpenLayers 2.10 Beginner's Guide, Packt Publishing. He has worked as the lead developer for a GIS-based company, has done contracting work with the design studio, Stamen, and has co-founded two start-ups. Erik is passionate about mapping, game development, and data visualization. In his free time, he enjoys writing and teaching, and can be found at http://vasir.net.

Jorge Arévalo is a computer engineer from Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, UAM. He started developing web applications with JavaScript, PHP, and Python. In 2010, he began working with PostGIS and GDAL projects, after participating in GSoC 2009, creating the PostGIS Raster GDAL driver. He also writes a blog on GIS at http://www.libregis.org. Jorge Arévalo has co-written the book, Zurb Foundation 4 Starter, Packt Publishing. He has also worked as a reviewer for the books, PostGIS 2.0 Cookbook, OpenLayers Beginner's Guide (2nd edition), Memcached, Speed Up your Web Application, and QGIS Cookbook, all by Packt Publishing.

Gagan Bansal has done B.Tech in Civil Engineering and then pursued M.Tech in Remote Sensing. He is experienced in maps application development, geospatial database design, and large-scale mapping using satellite data and aerial photographs. He is also experienced in understanding various market problems and deriving a feasible GIS solution using open source software and database. Currently, he is working with Rediff.com as a maps architect and engaged in developing applications for visualization and overlay of news, socioeconomic data, and business data on maps.

Christopher Jennison is an application developer working in Western Massachusetts with experience in GIS application development and mobile platform development. He has worked in web advertising, mobile advertising and application development, and data science and mapping applications. He has worked for HitPoint Studios, as a brand game developer, and The United States Geological Survey, as well as his own private contracts.

Arnaud Vandecasteele is a map lover and an open source / open data evangelist. After his PhD in computer science and GIS, he decided to move to Canada to conduct research on OpenStreetMap and to promote the use of Open Source GIS software. His experience with OpenLayers started from the very beginning of the library in 2006. From his website (http://geotribu.net), he wrote several tutorials to help beginners to use OpenLayers. Currently, Arnaud runs a GIS consultancy firm called Mapali (http://mapali.re/) that creates online mapping applications and provides consultancy services in the fields of web cartography and online GIS using open source software to a wide range of clients in the Indian Ocean (Réunion island, Mauritius).

For support files and downloads related to your book, please visit www.PacktPub.com.

Did you know that Packt offers eBook versions of every book published, with PDF and ePub files available? You can upgrade to the eBook version at www.PacktPub.com and as a print book customer, you are entitled to a discount on the eBook copy. Get in touch with us at <service@packtpub.com> for more details.

At www.PacktPub.com, you can also read a collection of free technical articles, sign up for a range of free newsletters and receive exclusive discounts and offers on Packt books and eBooks.

https://www2.packtpub.com/books/subscription/packtlib

Do you need instant solutions to your IT questions? PacktLib is Packt's online digital book library. Here, you can search, access, and read Packt's entire library of books.

If you have an account with Packt at www.PacktPub.com, you can use this to access PacktLib today and view 9 entirely free books. Simply use your login credentials for immediate access.

Web mapping is the process of designing, implementing, generating, and delivering maps on the Web and its products. OpenLayers is a powerful, community-driven, open source, pure JavaScript web mapping library. With this, you can easily create your own web map mashup using a myriad of map backends. Interested in knowing more about OpenLayers?

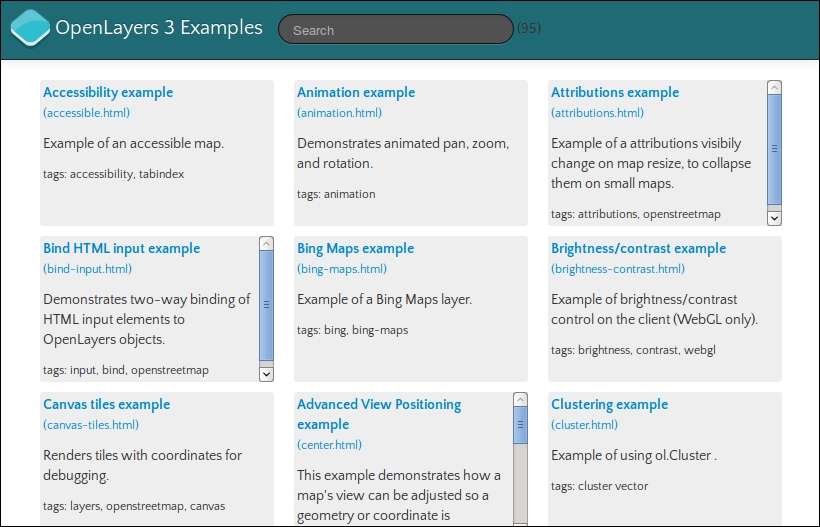

This book is going to help you learn OpenLayers from scratch. OpenLayers 3 Beginner's Guide will walk you through the OpenLayers library in the easiest and most efficient way possible. The core components of OpenLayers are covered in detail, with examples, structured so that you can easily refer back to them later.

The book starts off by showing you how to create a simple map and introduces you to some basic JavaScript programming concepts and tools. You will also find useful resources to learn more about HTML and CSS. Through the course of this book, we will review each component needed to make a map in OpenLayers 3, and you will end with a full-fledged web map application.

You will learn some context to help you understand the key role of each OpenLayers 3 component in making a map. You will also learn important mapping principles such as projections and layers. Maps require sources of data as well; so, you will see how to create your own data files and connect to backend servers for mapping. A key part of this book will also be dedicated to building a mapping application for mobile devices and its specific components.

With OpenLayers 3 Beginner's Guide, you will learn how to create your own map applications independently, without being stuck at the first stage of learning. You will acquire the information you need to develop your skills and knowledge of the OpenLayers 3 library.

Chapter 1, Getting Started with OpenLayers will introduce you to OpenLayers 3 and will help you to learn some basic mapping principles. You will see how to get ready for development in OpenLayers and create your first map.

Chapter 2, Key Concepts in OpenLayers will introduce the main components of the OpenLayers library and illustrate how they are related. We will introduce some key concepts, including events and observable properties, and learn some basic debugging techniques.

Chapter 3, Charting the Map Class will describe two of the core components, the Map and View classes, in detail. We will learn about the properties, methods, and events of both classes and apply them in practical examples.

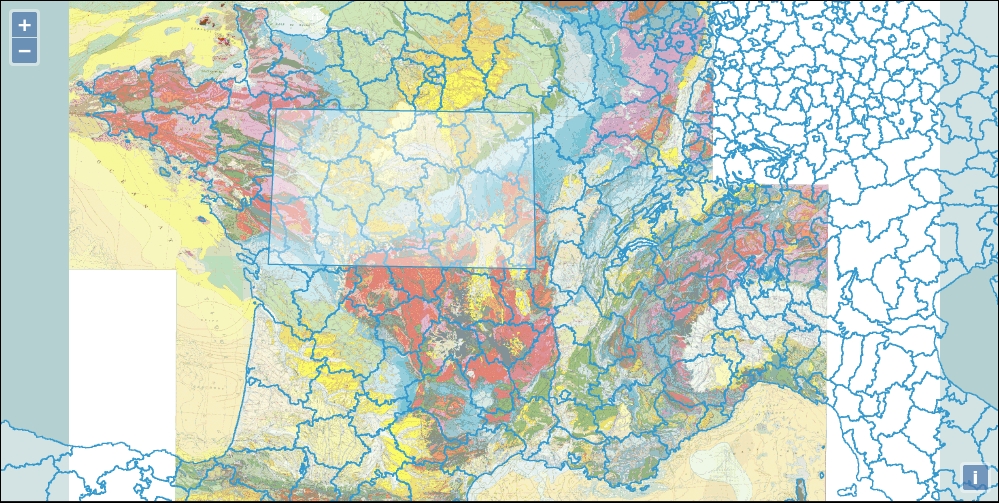

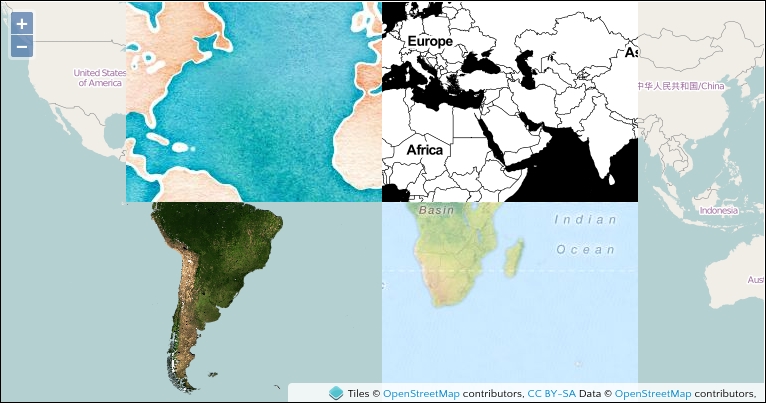

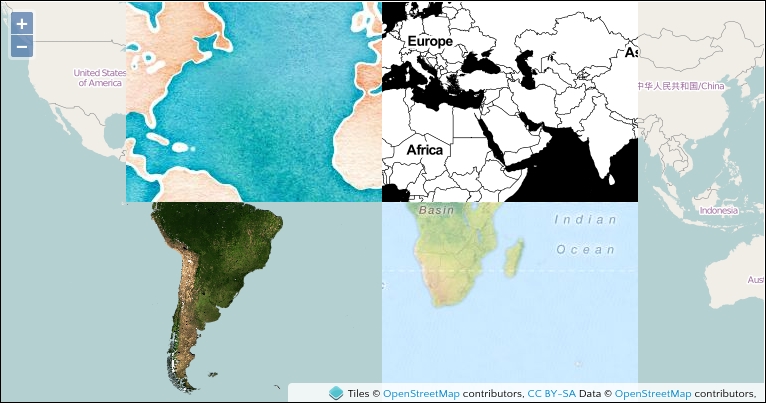

Chapter 4, Interacting with Raster Data Source will introduce the concept of layers and focus on raster layers. We will explain the difference between tiled and untiled layers and learn how to use OpenLayers to visualize any type of image, even non-geospatial ones.

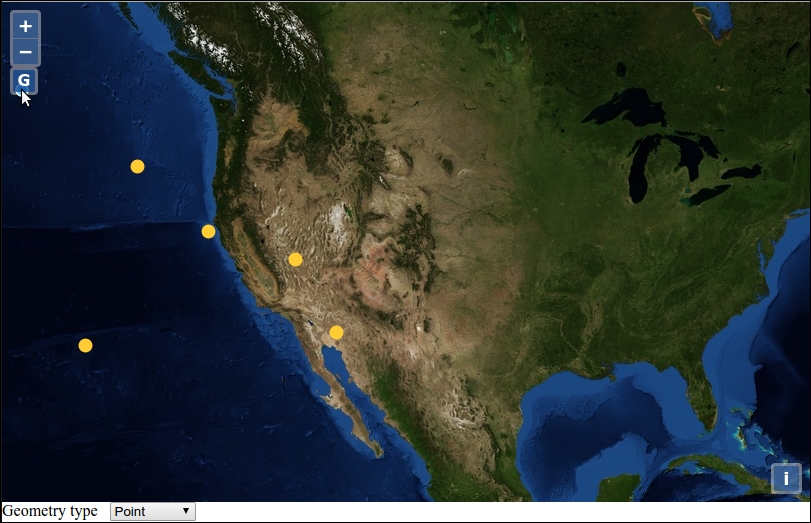

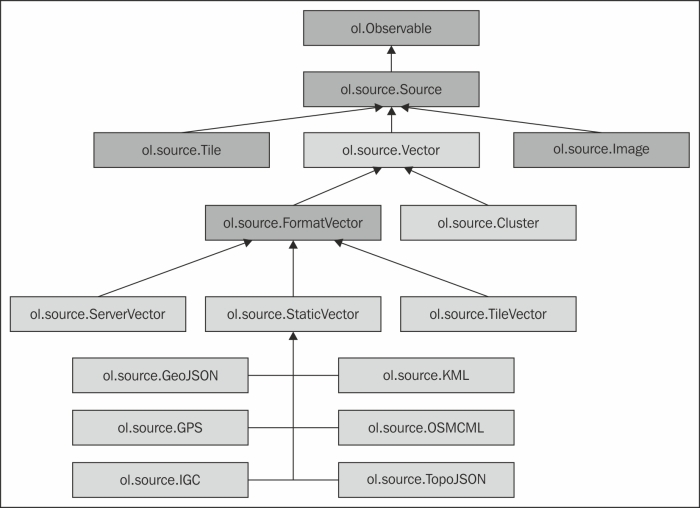

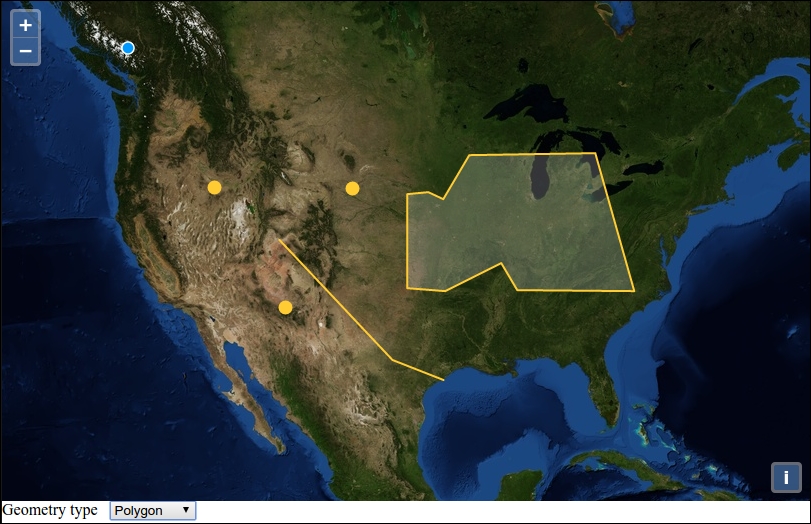

Chapter 5, Using Vector Layers will introduce vector layers and the related source, format, feature, and geometry classes. We will learn the properties, methods, and events associated with each, and how to use them to load a variety of vector data into an OpenLayers map.

Chapter 6, Styling Vector Layers will expand on our knowledge of vector layers by learning how to apply both static and dynamic styles to them. Through hands-on examples, we'll learn how to modify styles interactively in response to user interaction.

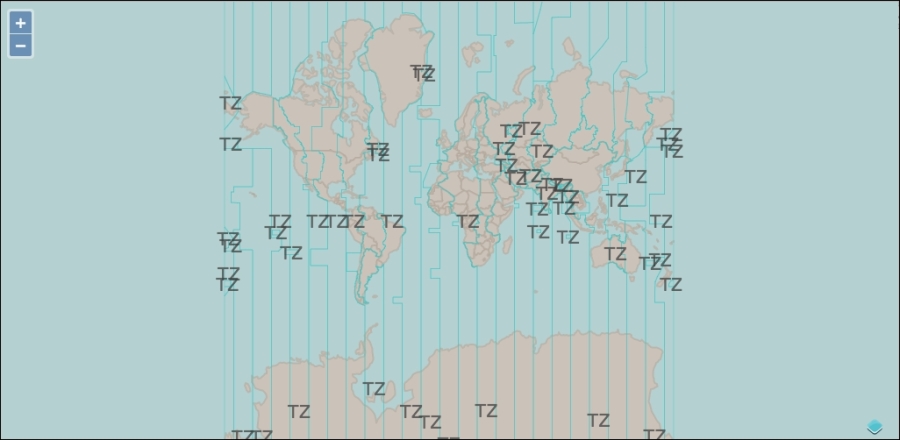

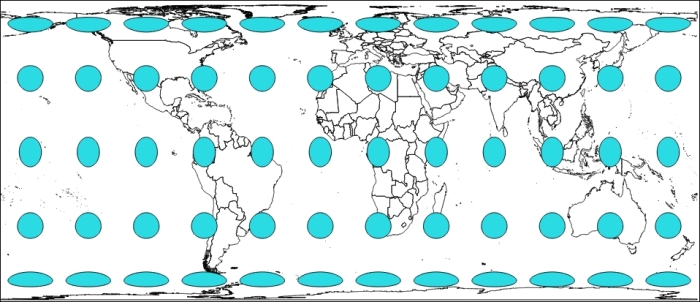

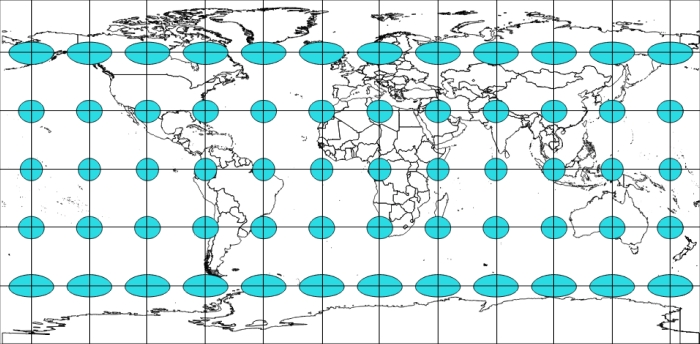

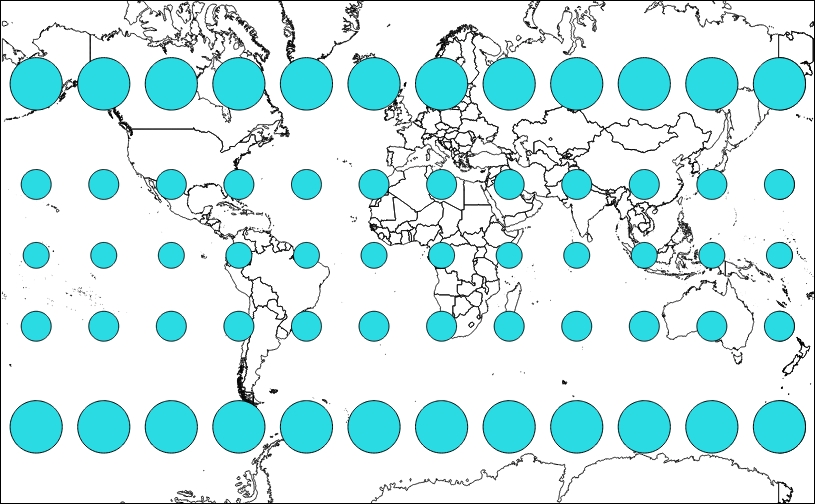

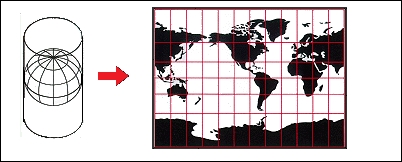

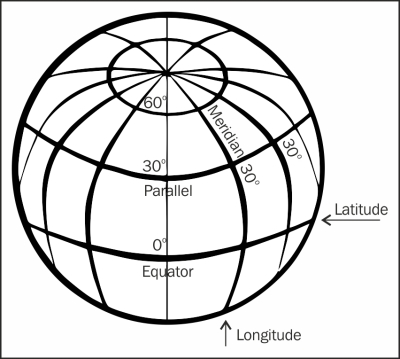

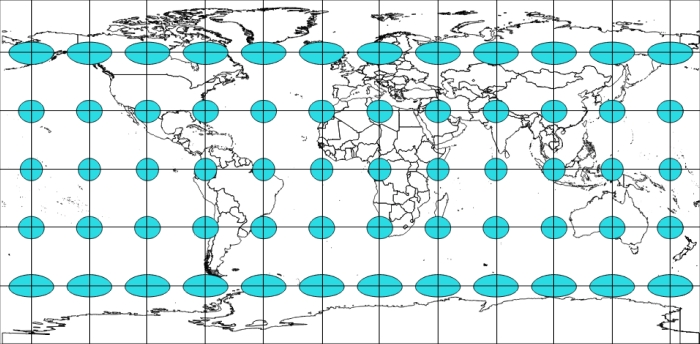

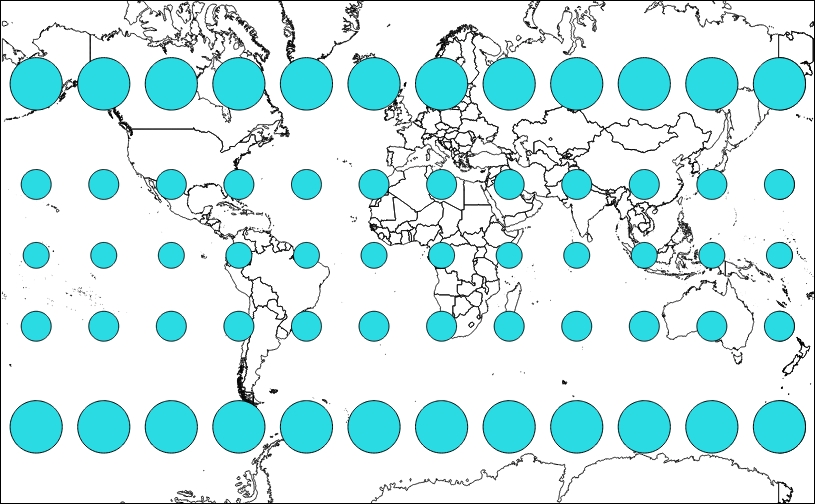

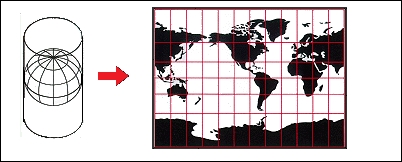

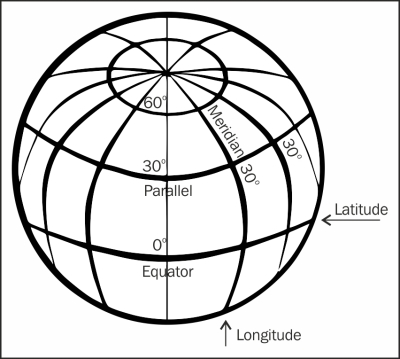

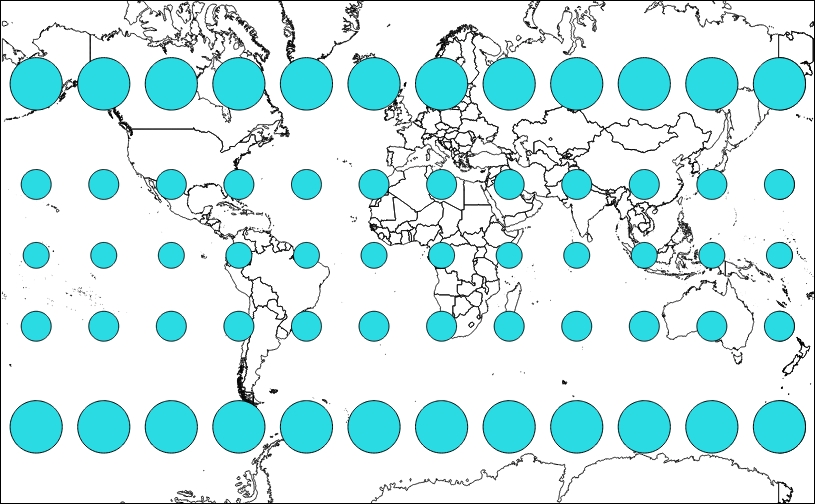

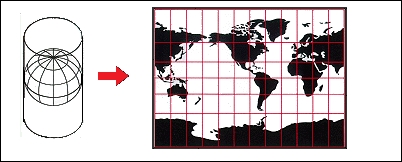

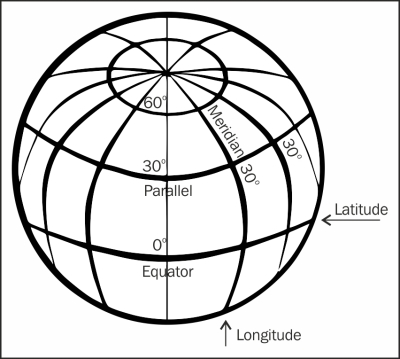

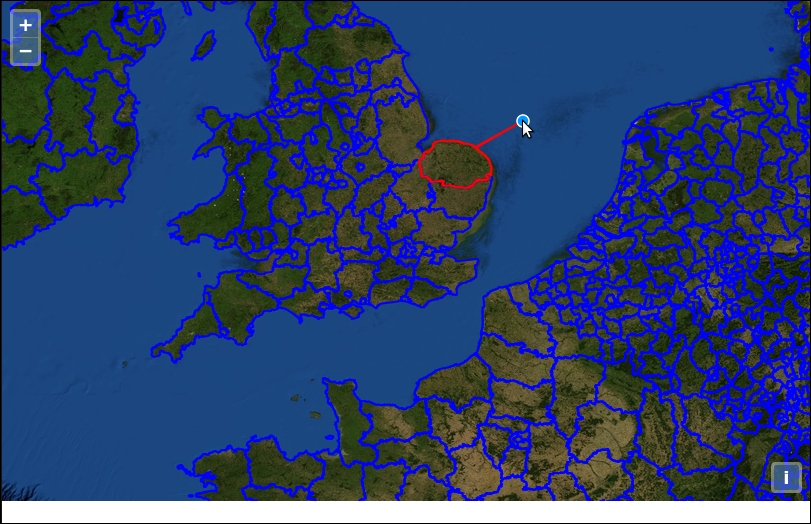

Chapter 7, Wrapping Our Heads Around Projections will cover the basic concepts behind map projections and their characteristics. We will cover projection support within OpenLayers by introducing the Proj4js library and applying it to map, vector, and raster layers.

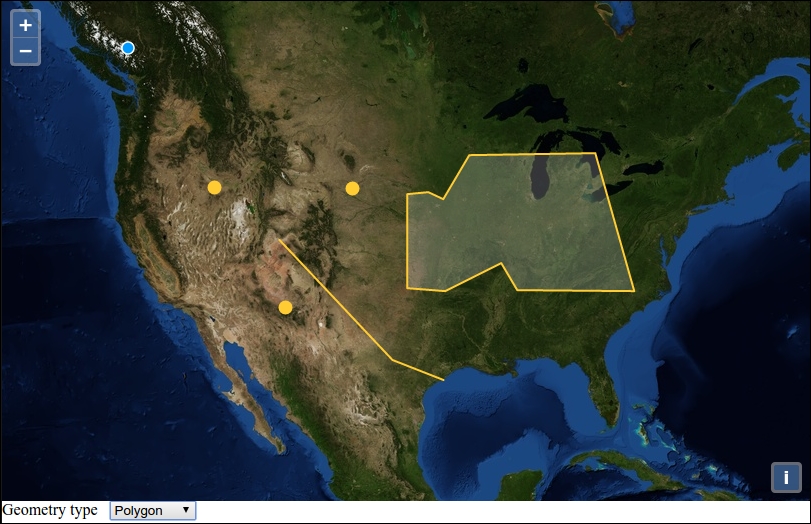

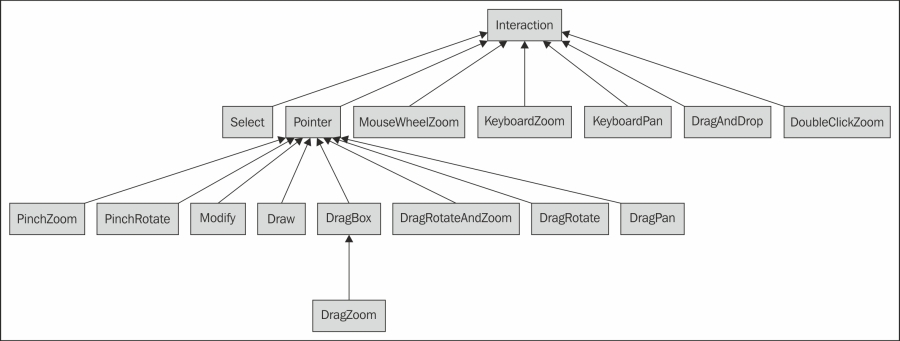

Chapter 8, Interacting with Your Map will dive into the concept of interactions and introduce the default interactions. After covering the available interactions in detail, we will finish with an example showing how to use interactions to draw a rectangle.

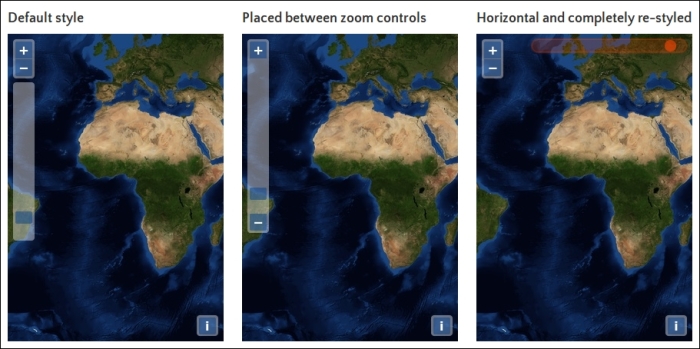

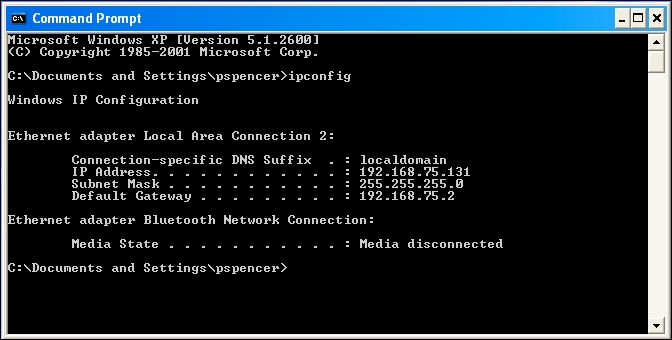

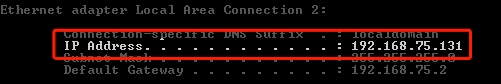

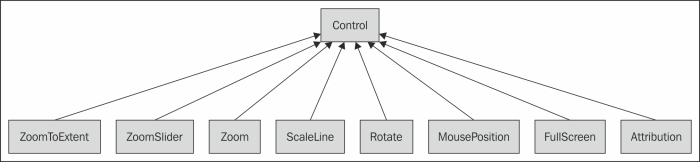

Chapter 9, Taking Control of Controls will demonstrate the use of controls and introduce the default controls provided by OpenLayers. We will also review each of the controls in more detail and learn how to make a custom control.

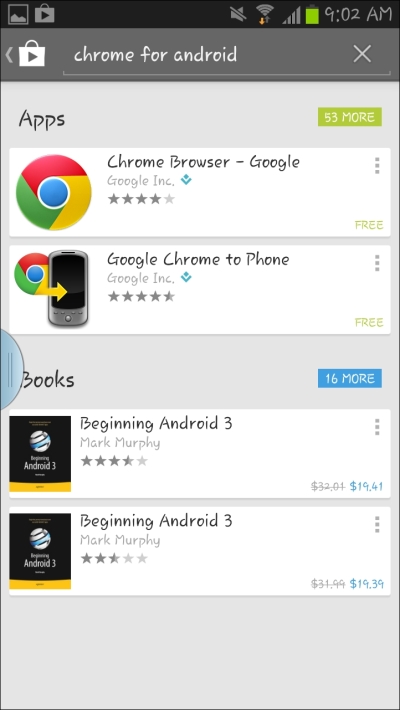

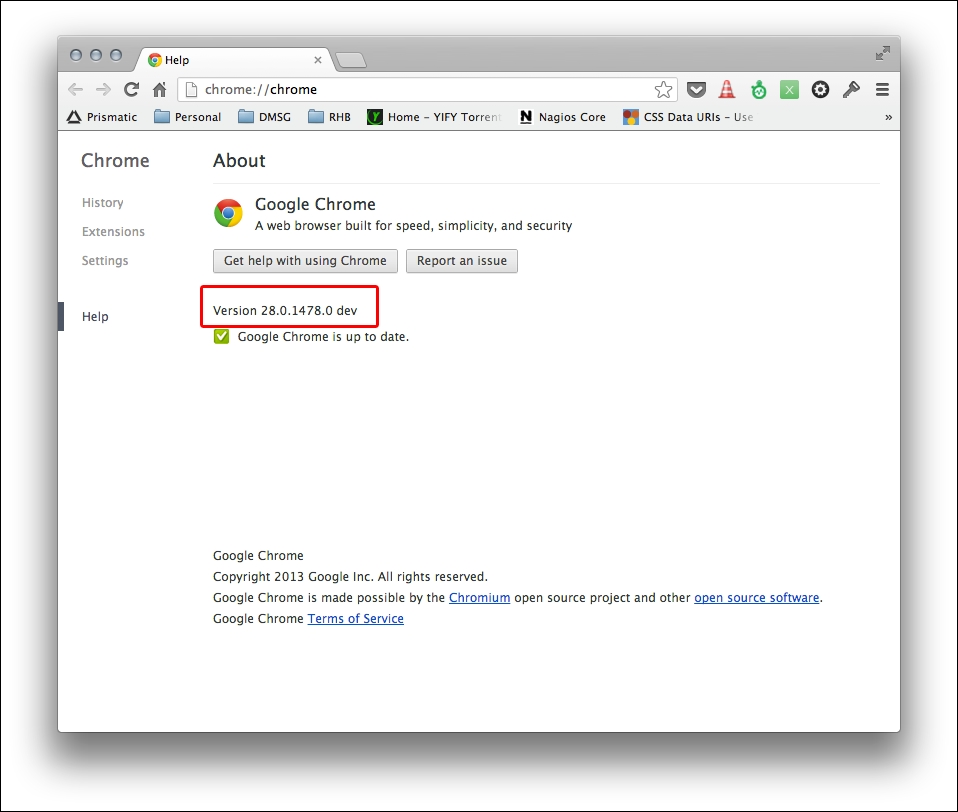

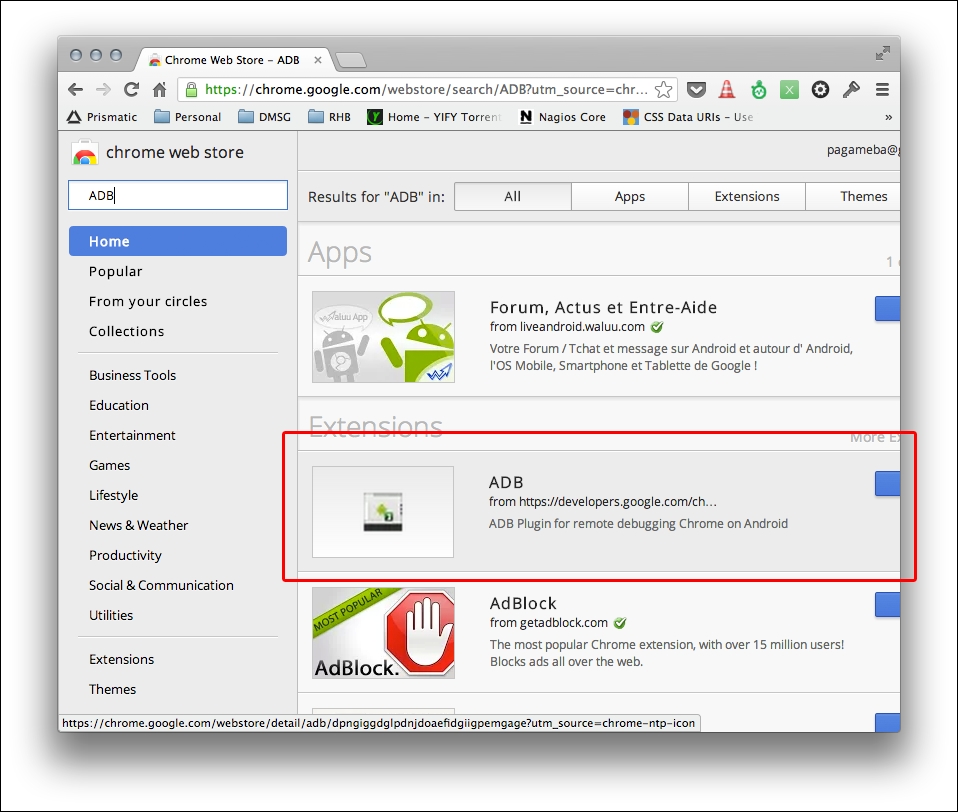

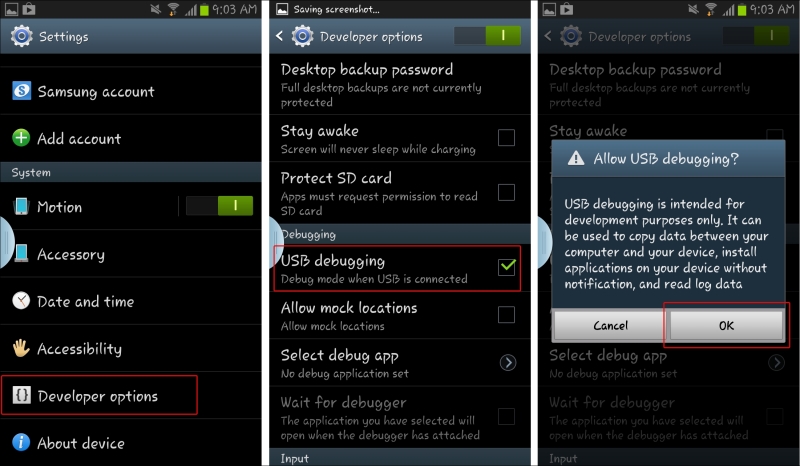

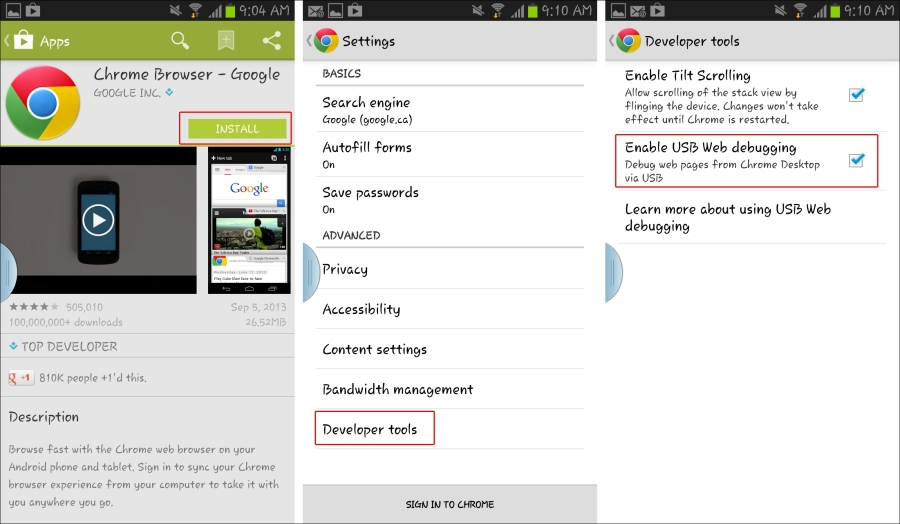

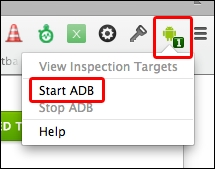

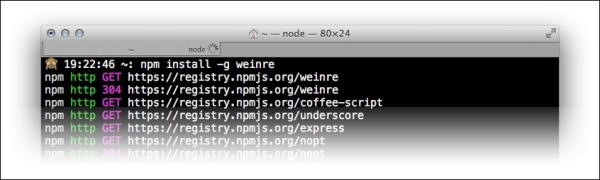

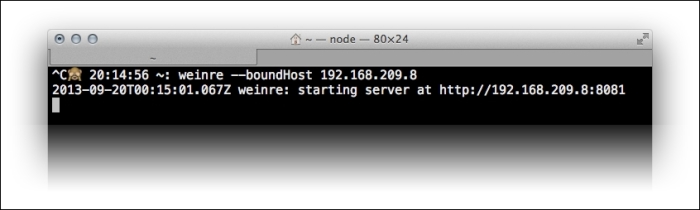

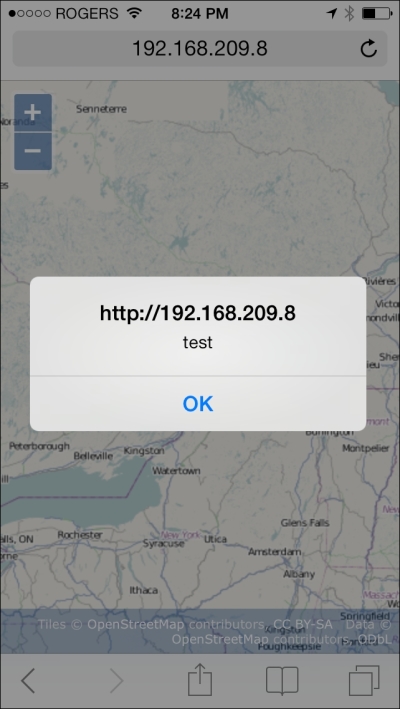

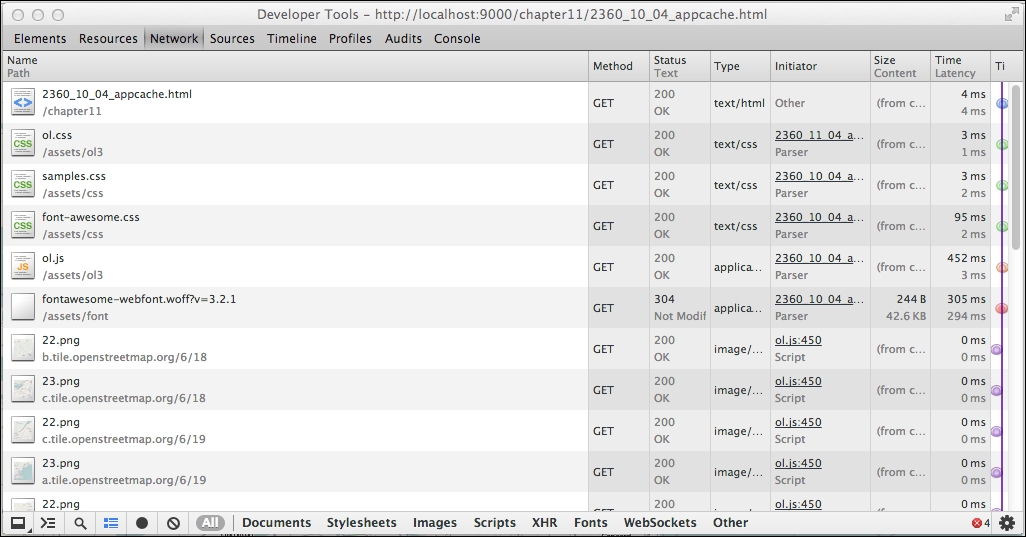

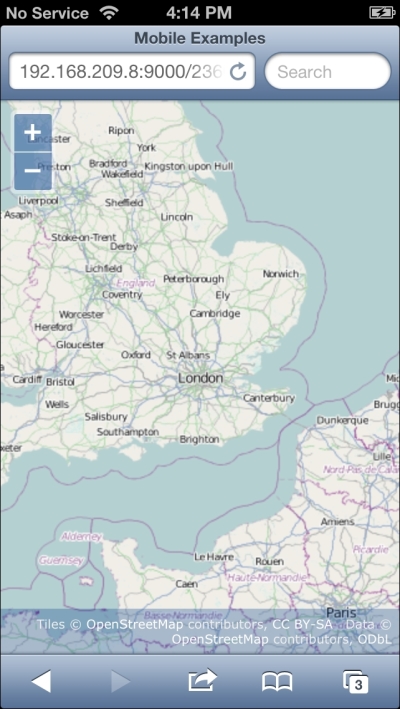

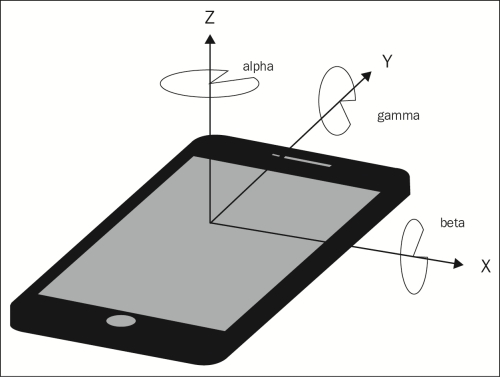

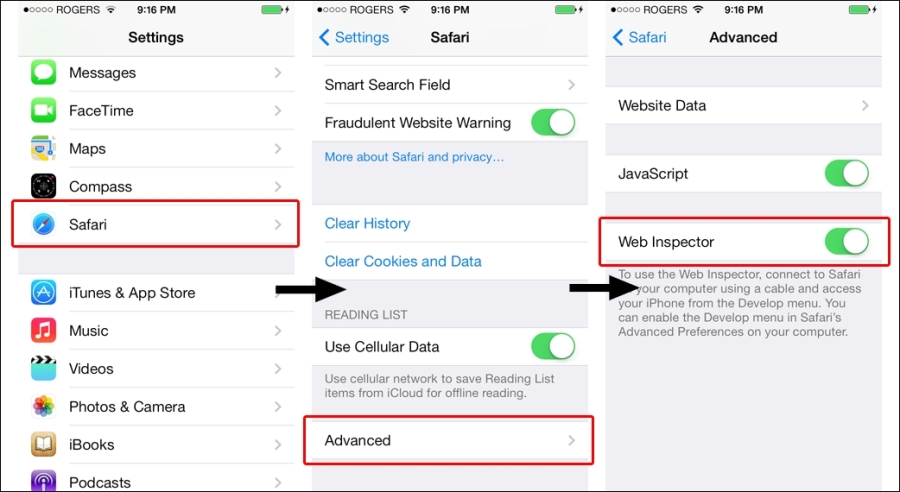

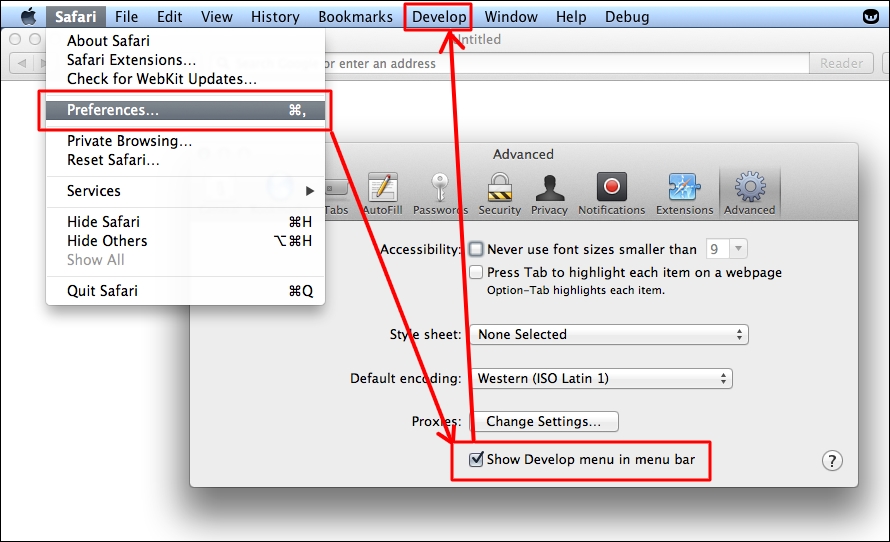

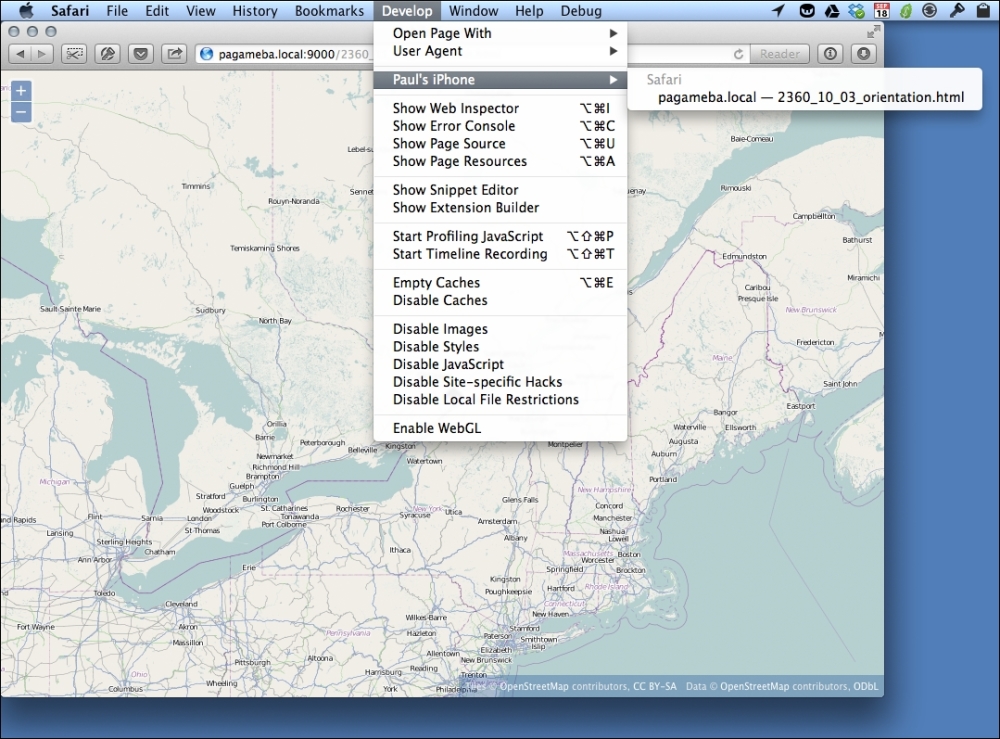

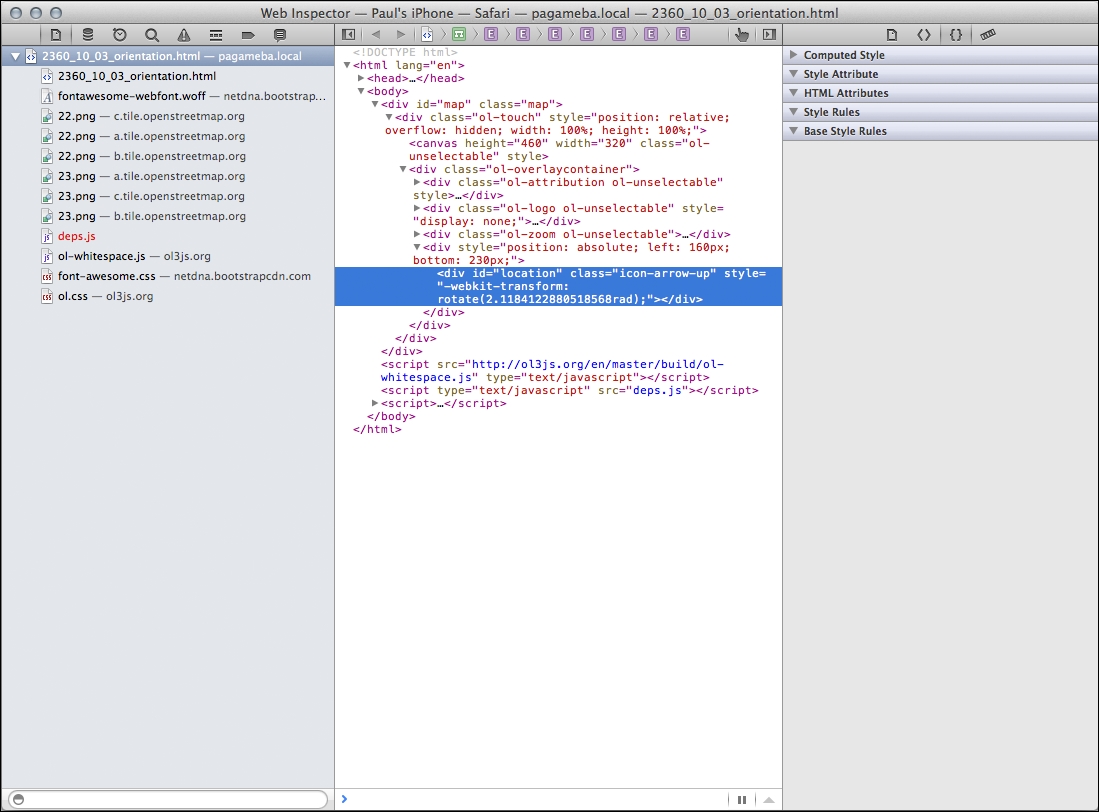

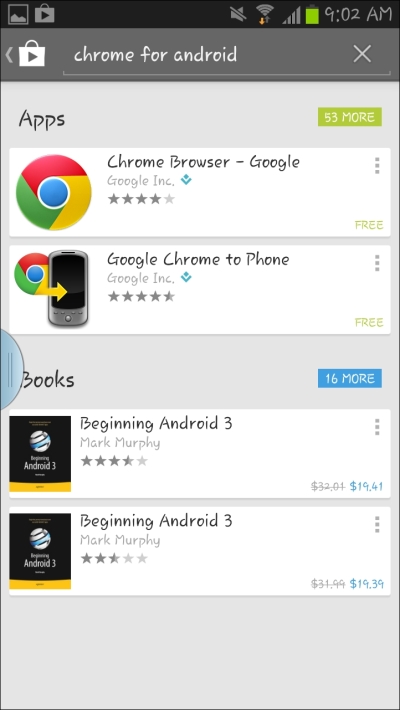

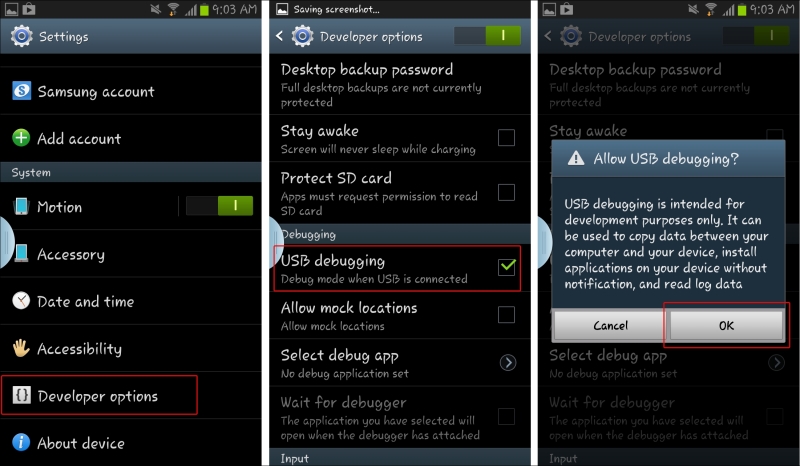

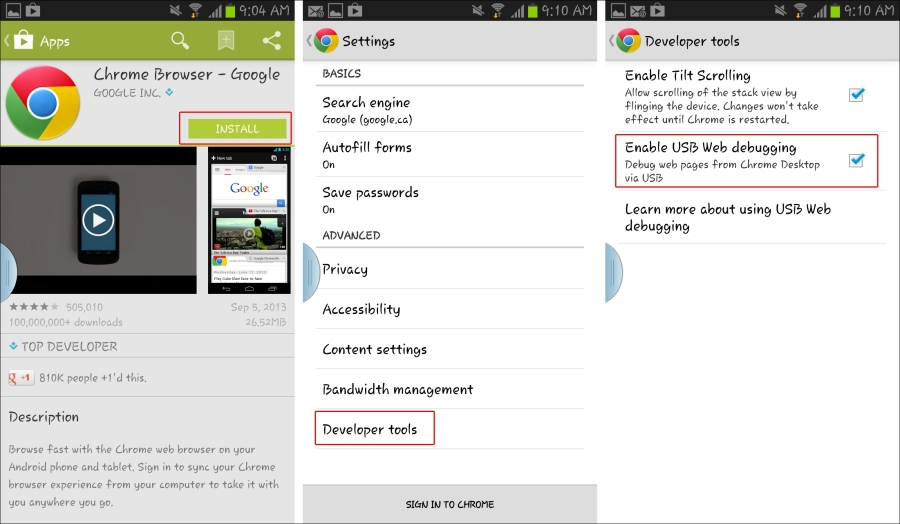

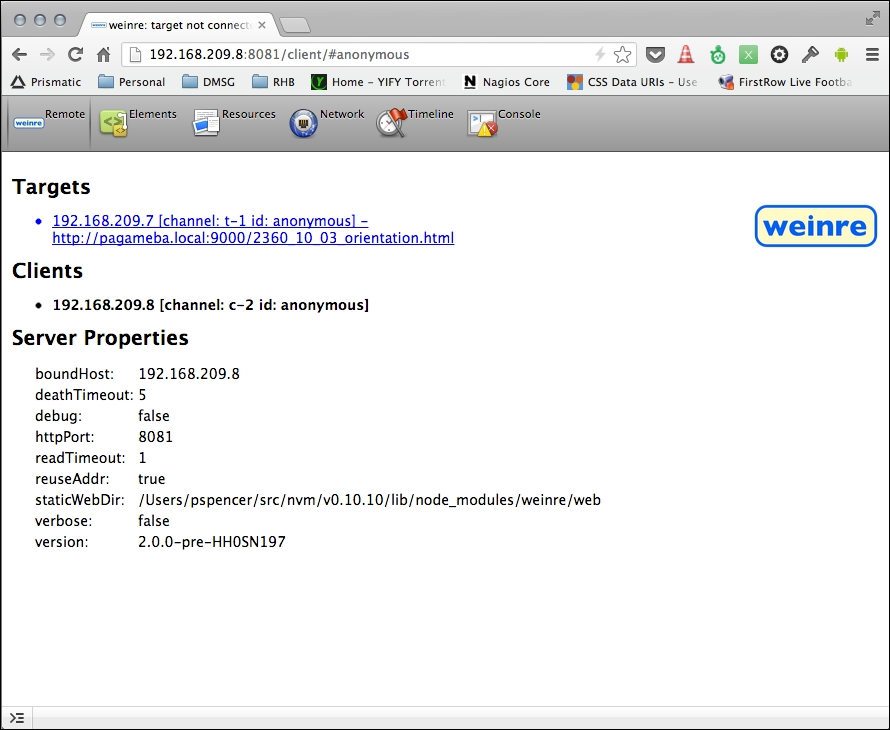

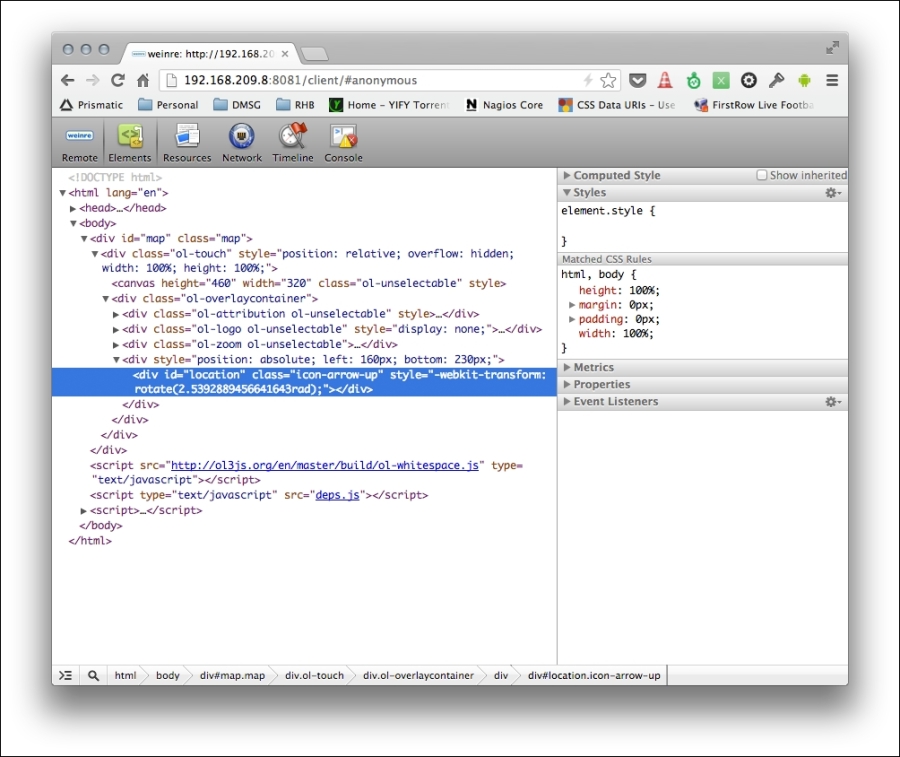

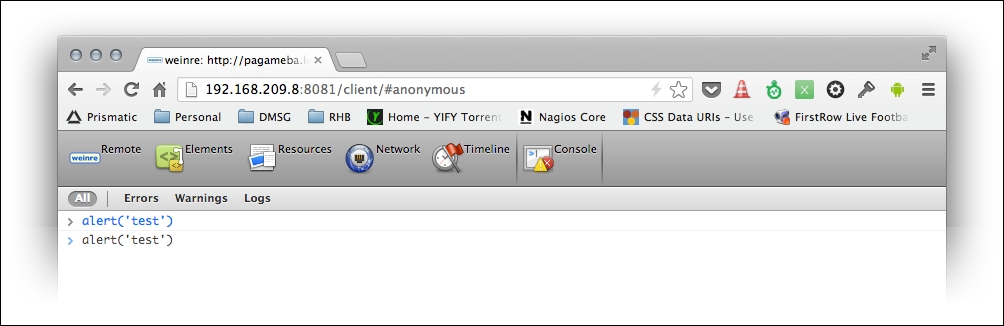

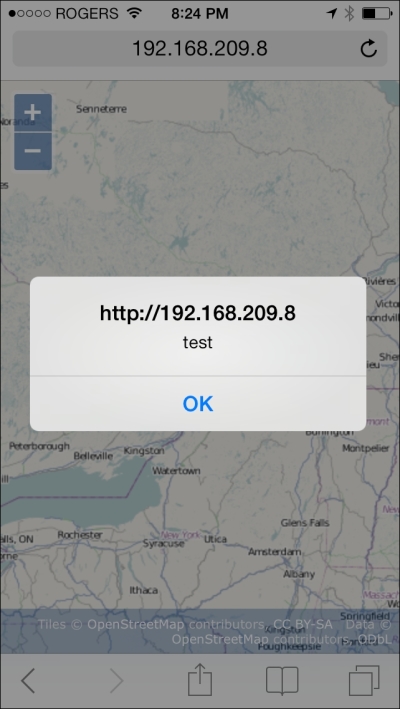

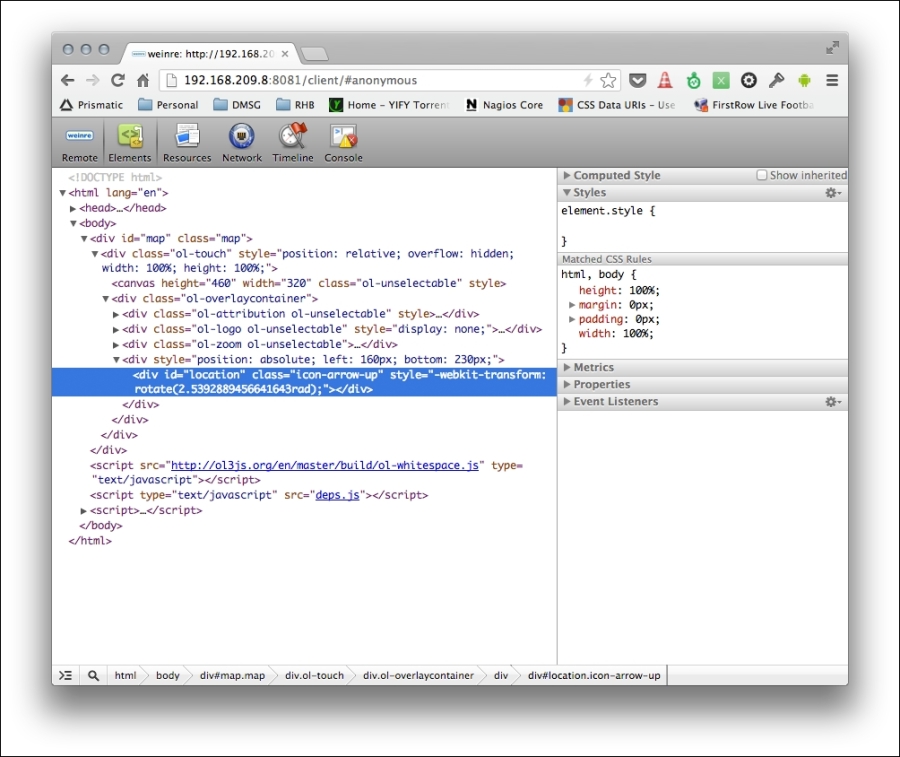

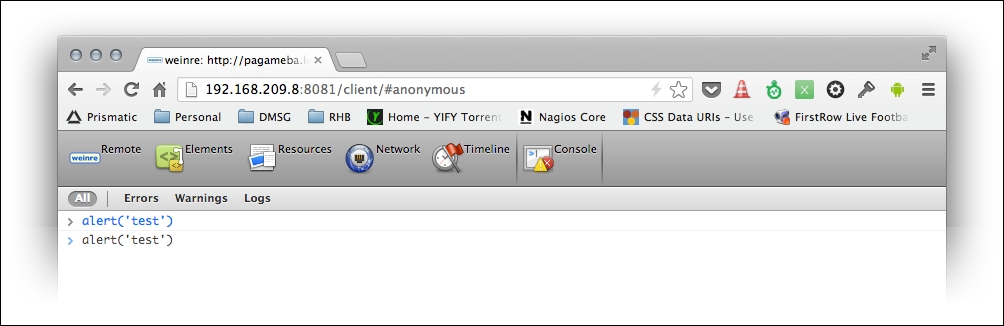

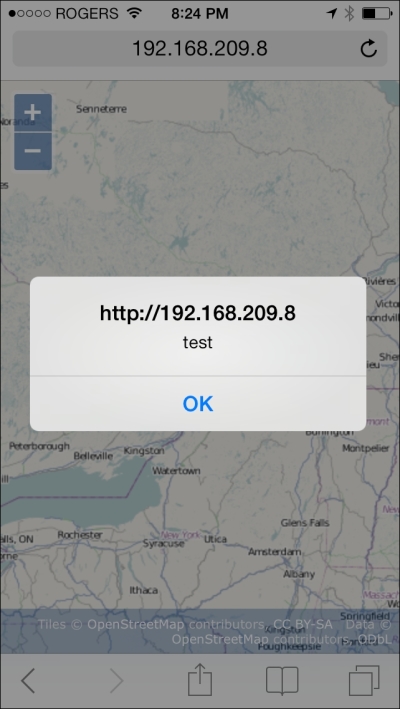

Chapter 10, OpenLayers Goes Mobile will teach us to take advantage of mobile-specific features such as Geolocation and Device Orientation. We will also learn how to debug mobile web applications and look at some mobile-specific browser features that can be useful for geospatial applications.

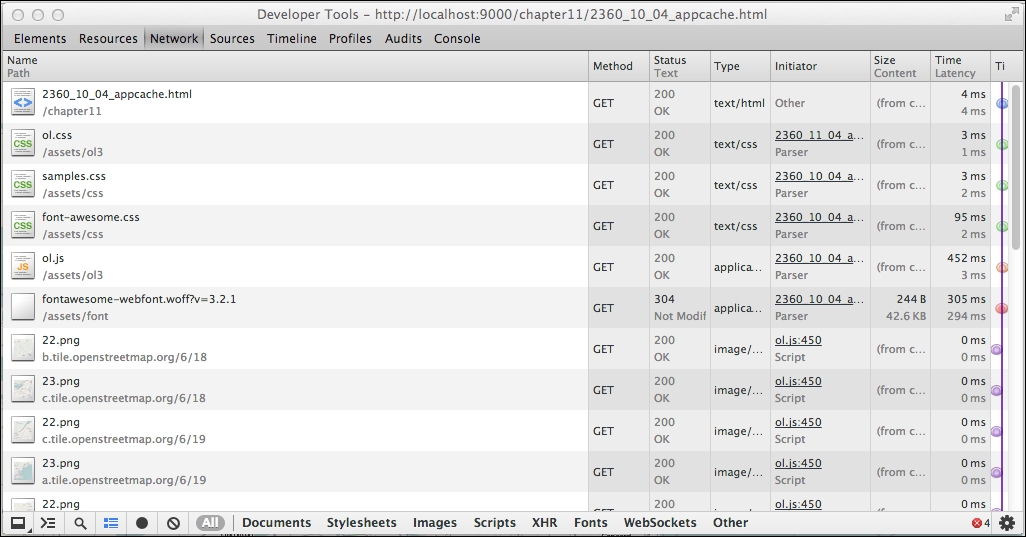

Chapter 11, Creating Web Map Apps will build a complete application from scratch and learn how to use the OpenLayers build system to create a production-ready application from our code.

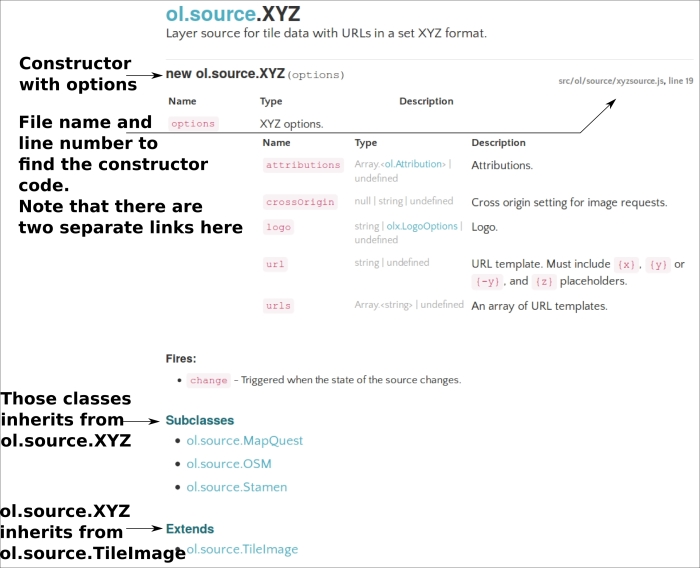

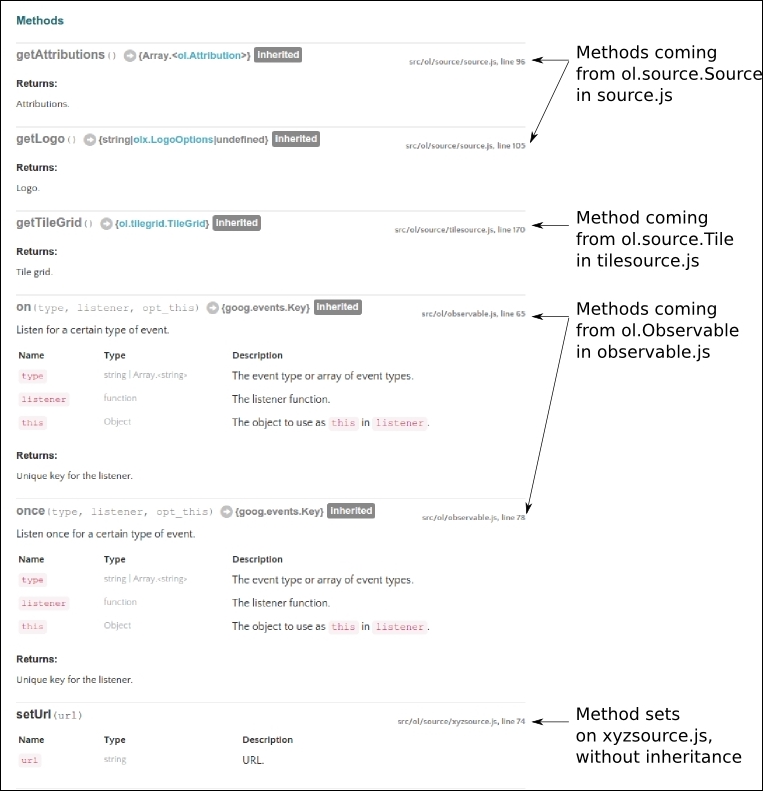

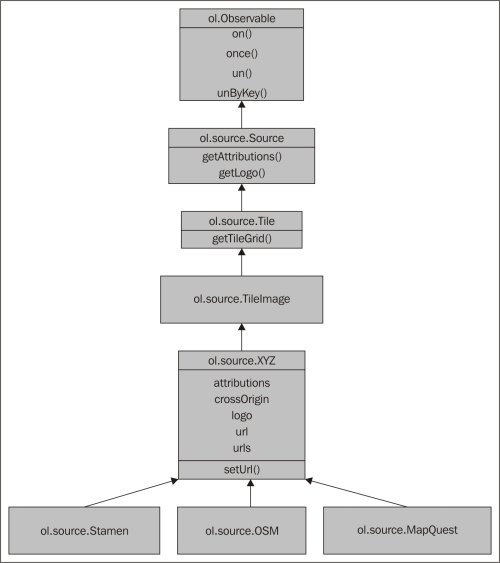

Appendix A, Object-oriented Programming – Introduction and Concepts covers the main concepts of Object-oriented Programming (OOP). After, we will discover how to reuse them exploring the OpenLayers API documentation with OOP in mind.

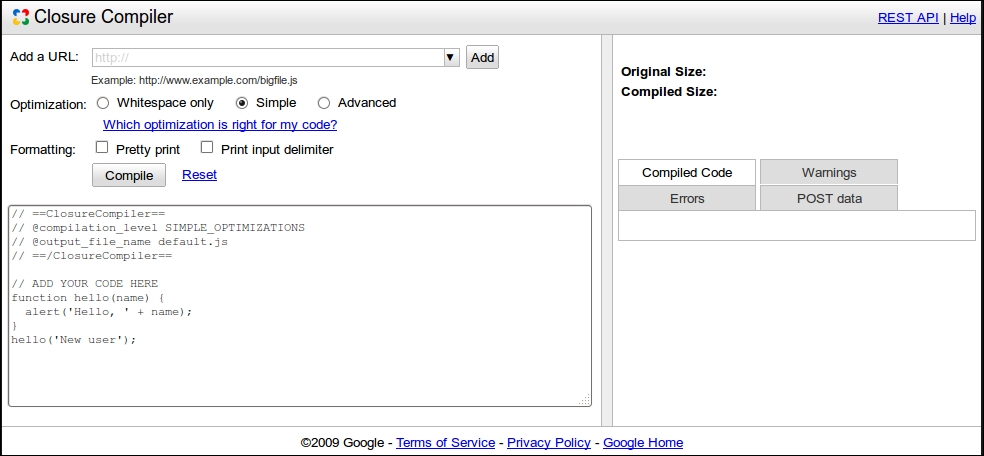

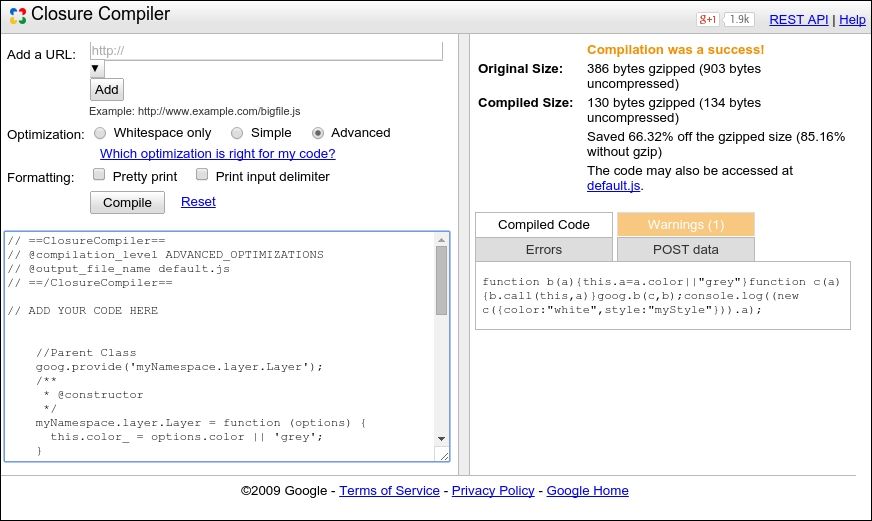

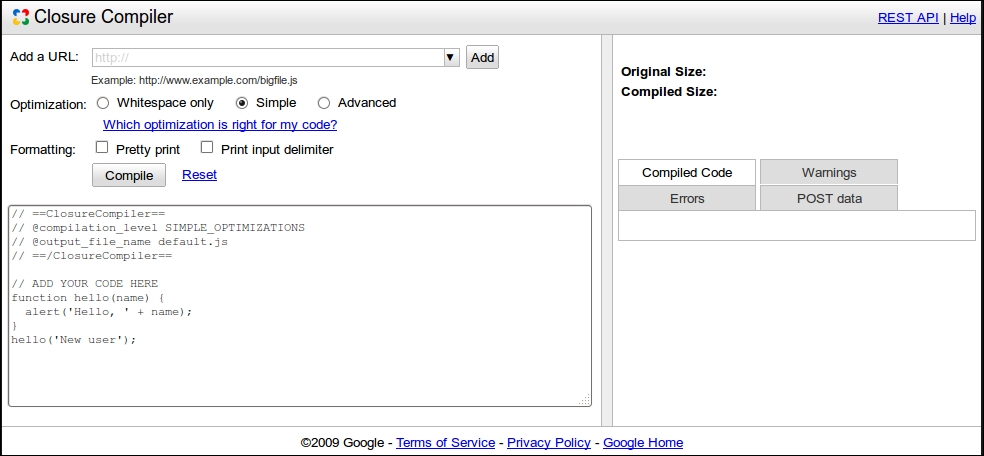

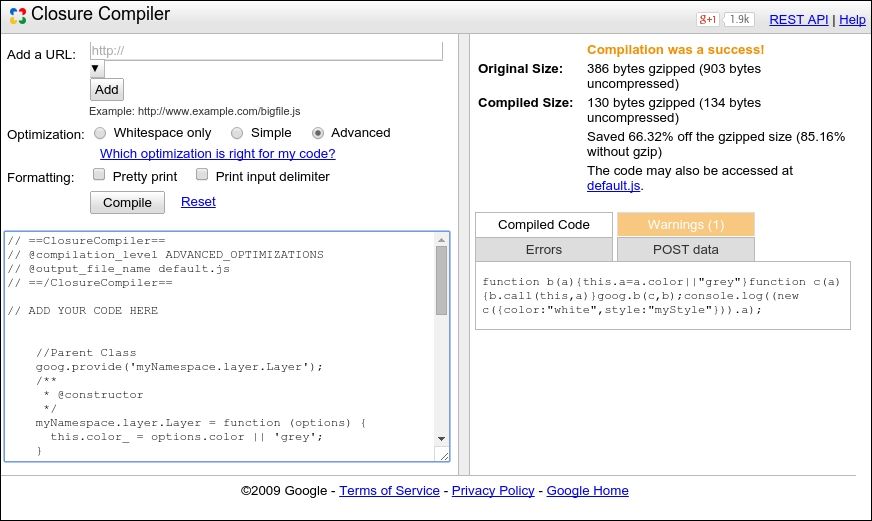

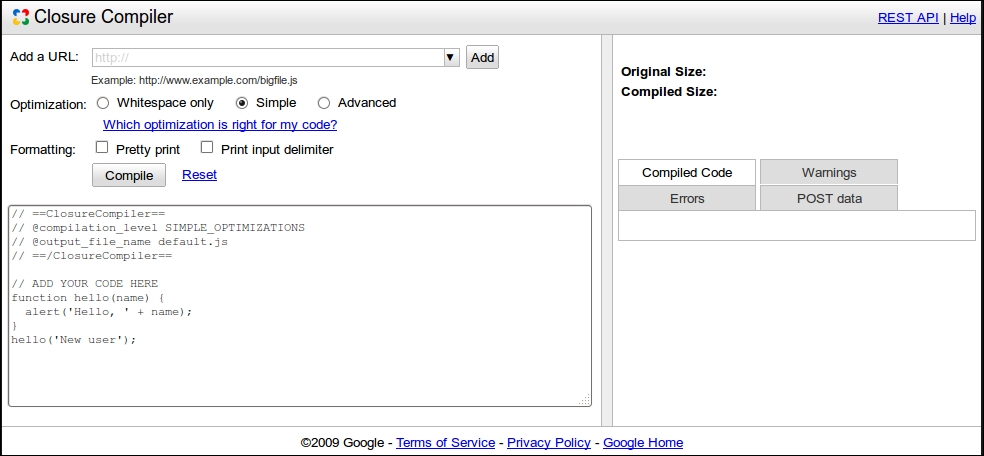

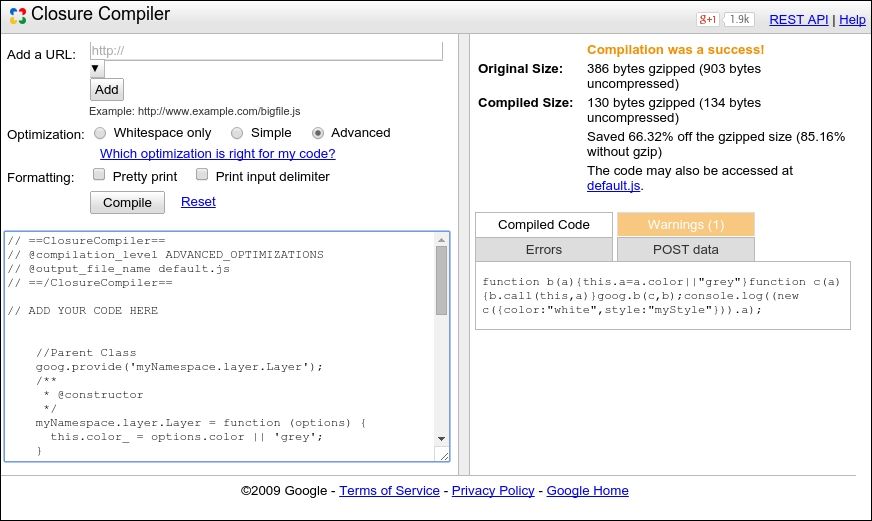

Appendix B, More details on Closure Tools and Code Optimization Techniques will cover more details on Closure Tools and code optimization techniques. This appendix introduces Closure Tools, a set of tools that OpenLayers 3 library relies on. It provides an understanding on how to use the Closure Library and Closure Compiler with a focus on compressing OpenLayers code files. We will finish with a review of styles and syntax for good coding practices.

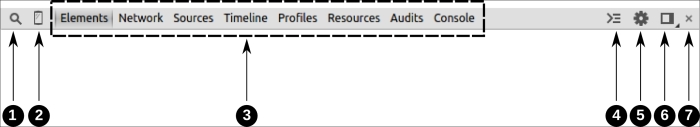

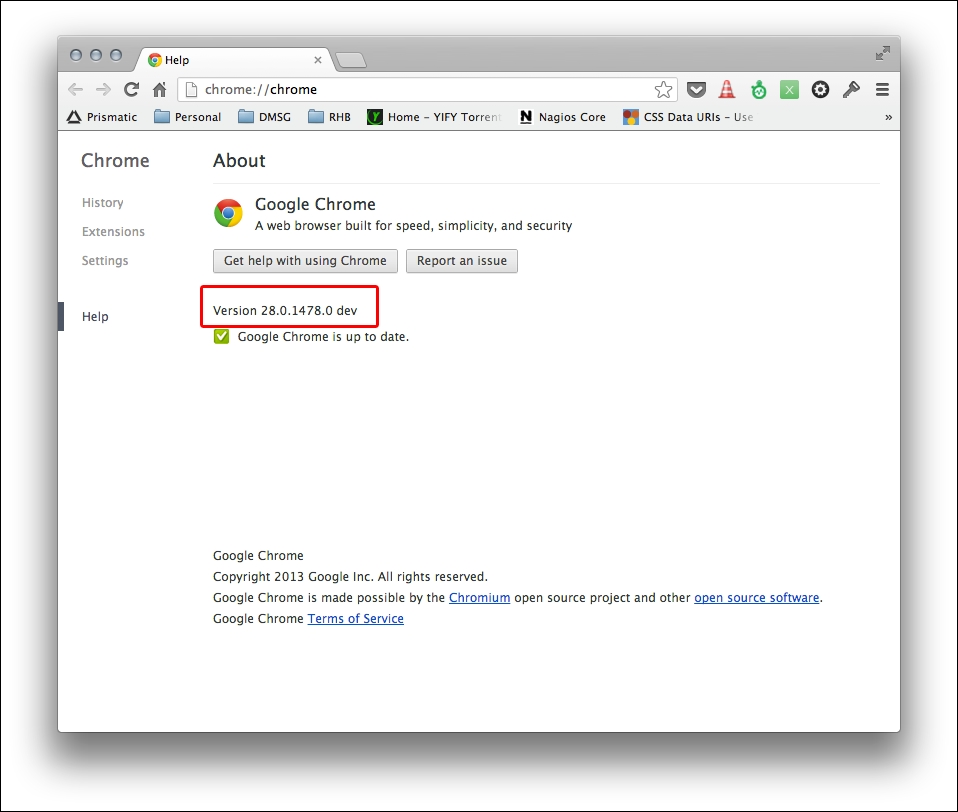

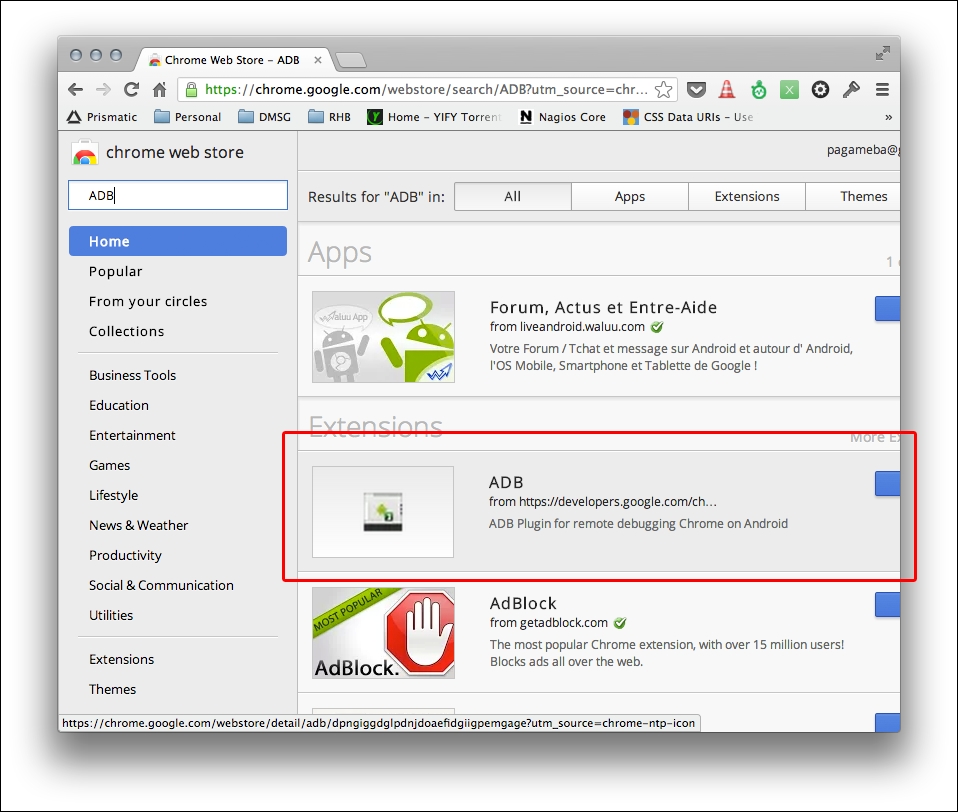

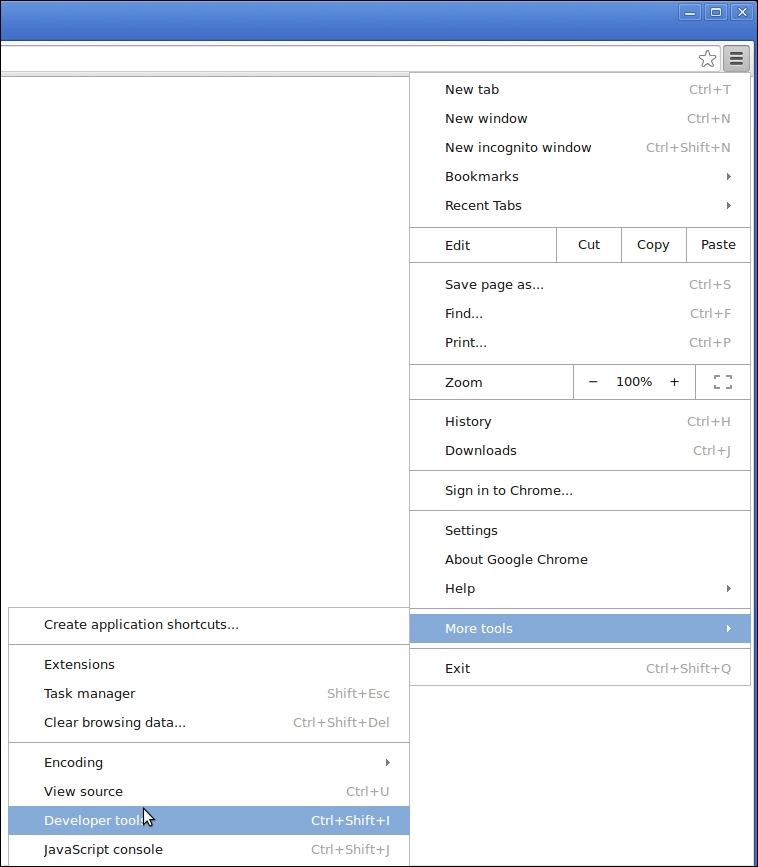

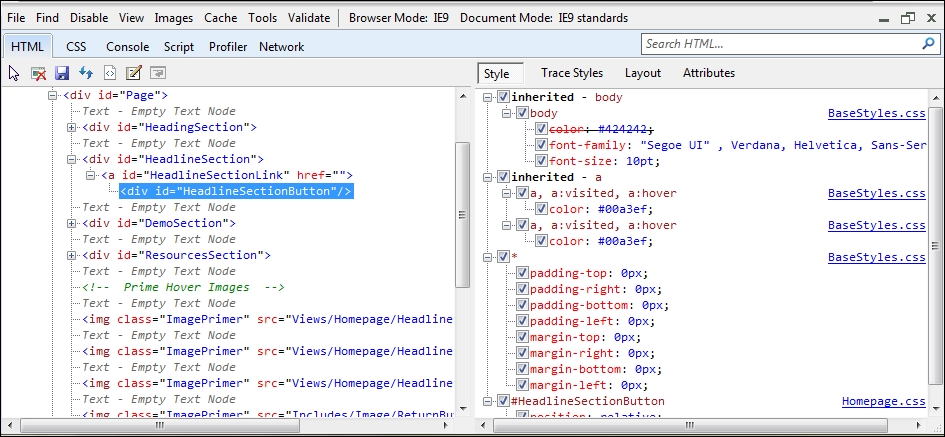

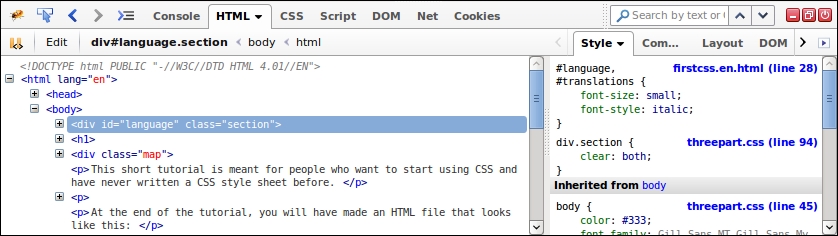

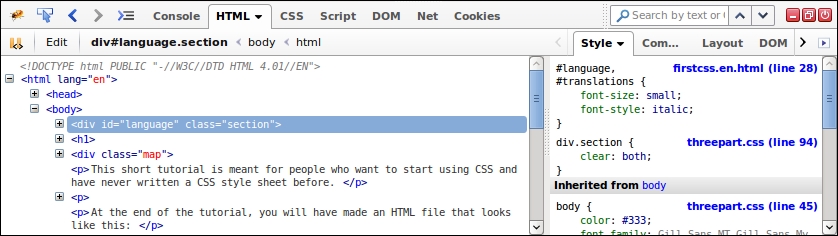

Appendix C, Squashing Bugs with Web Debuggers provides JavaScript beginners with an in-depth review of browser developer tools. We will review Chrome Developer Tools, additional extensions and finish with debugging tools in other browsers such as IE and Firefox.

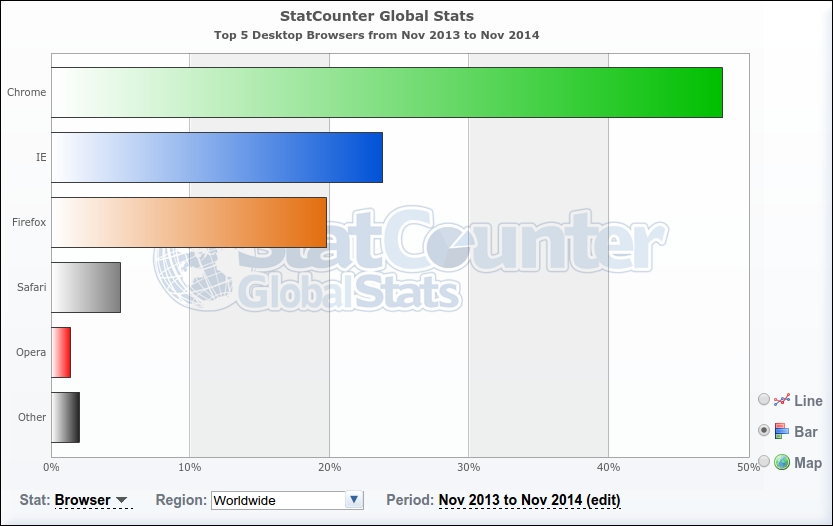

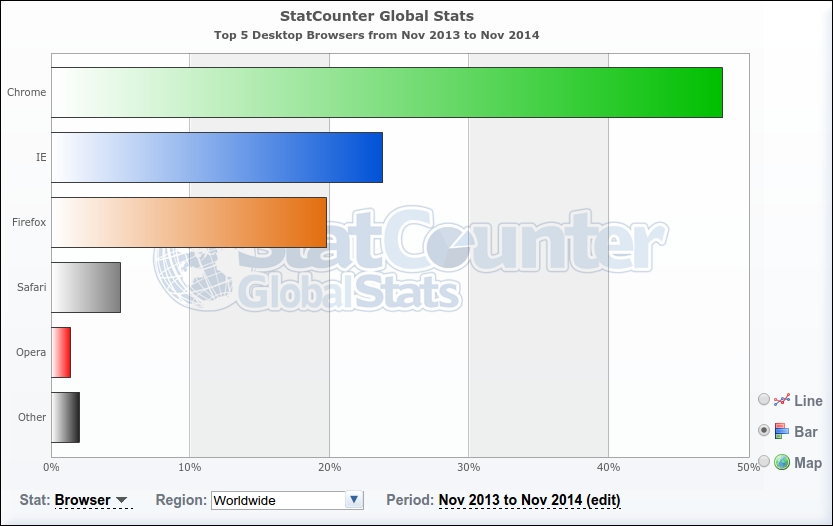

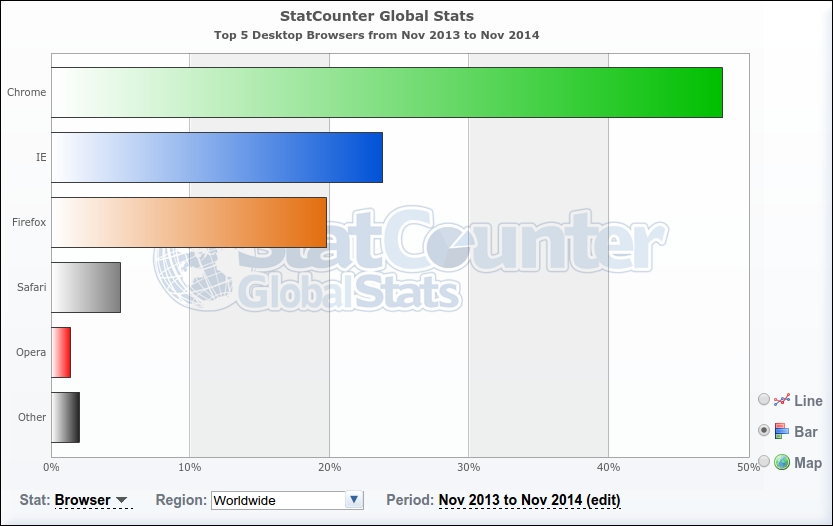

The main thing you'll need for this book is a computer and text editor. Your operating system will come with a text editor, any will do, but you will likely find that a text editor focused on developer needs will be most useful. There are many excellent developer-oriented text editors available for various operating systems, see https://github.com/showcases/text-editors and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_text_editors for some options. An Internet connection will be required to view the maps, and you'll also need a recent version of a modern web browser, such as Firefox, Google Chrome, Safari, Opera, or Internet Explorer (version 9 or higher).

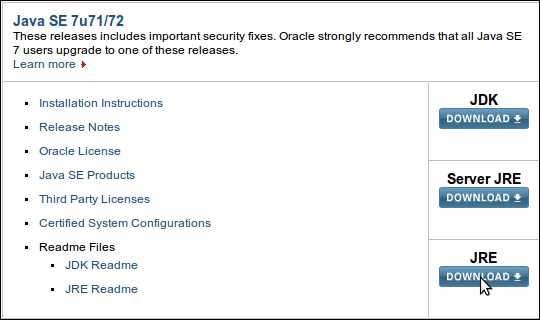

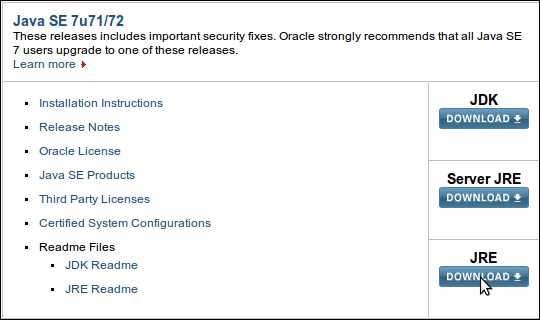

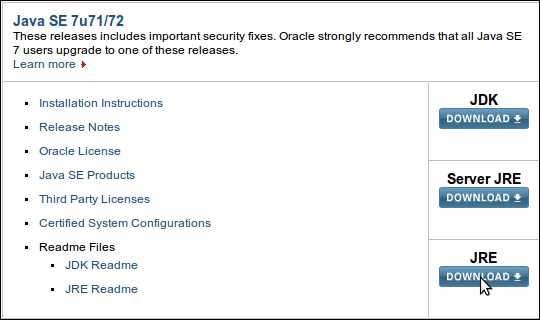

For some advanced uses cases, you will also need Python, NodeJS, Java, and Git (a source code control management software). Installation instructions are provided for these additional tools.

No knowledge of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) is required, nor is extensive JavaScript experience. A basic understanding of JavaScript syntax and HTML/CSS will greatly aid in understanding the material, but is not required.

This book is for anyone who has an interest in using maps on their website, from hobbyists to professional web developers. OpenLayers provides a powerful, but easy-to-use, pure JavaScript and HTML (no third-party plug-ins involved) toolkit to quickly make cross-browser web maps. A basic understanding of JavaScript will be helpful, but there is no prior knowledge required to use this book. If you've never worked with maps before, this book will introduce you to some common mapping topics and gently guide you through the OpenLayers 3 library. If you're an experienced application developer, this book will also serve as a reference to the core components of OpenLayers 3.

Instructions often need some extra explanation to ensure they make sense, so they are followed with these sections:

This section explains the working of the tasks or instructions that you have just completed.

You will also find some other learning aids in the book, for example:

These are short multiple-choice questions intended to help you test your own understanding.

In this book, you will find a number of styles of text that distinguish between different kinds of information. Here are some examples of these styles, and an explanation of their meaning.

Code words in text, folder names, filenames, file extensions, pathnames, URLs, and user input are shown as follows: "You can name the folder whatever you like, but we'll refer to it as the sandbox folder."

A block of code is set as follows:

var map = new ol.Map({

target: 'map',

layers: [layer],

view: view

});When we wish to draw your attention to a particular part of a code block, the relevant lines or items are set in bold:

var map = new ol.Map({

target: 'map',

view: view,

layers: [layer],

renderer: 'dom'

});Any command-line input or output is written as follows:

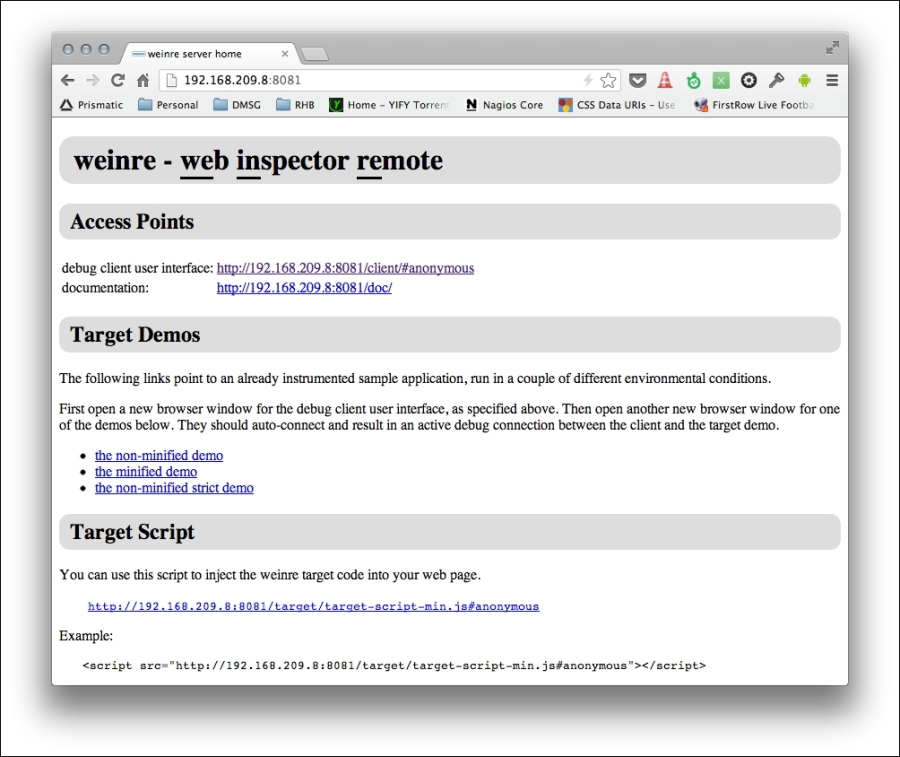

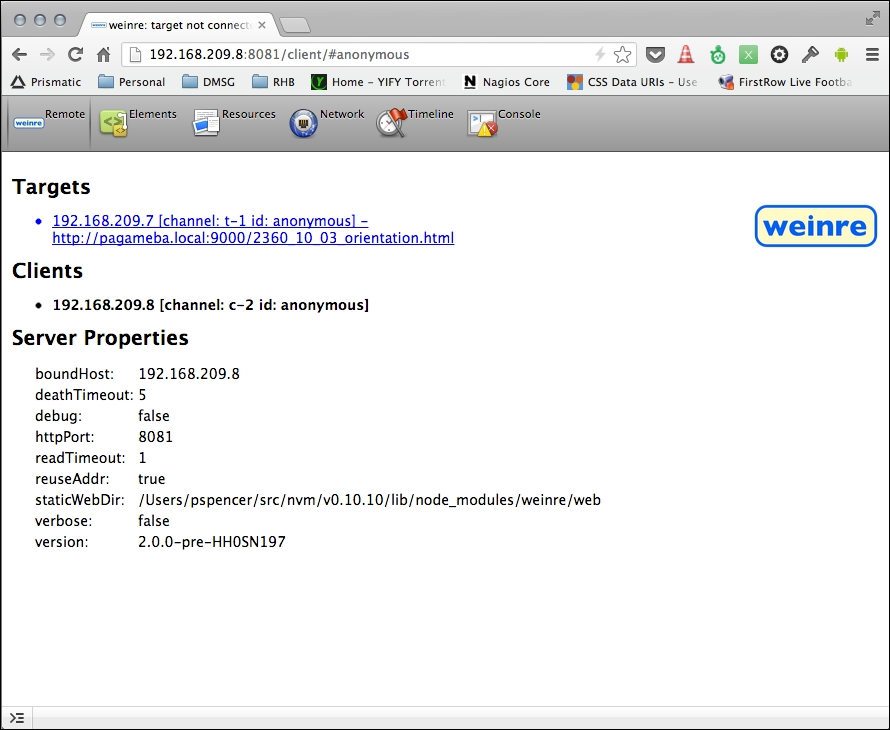

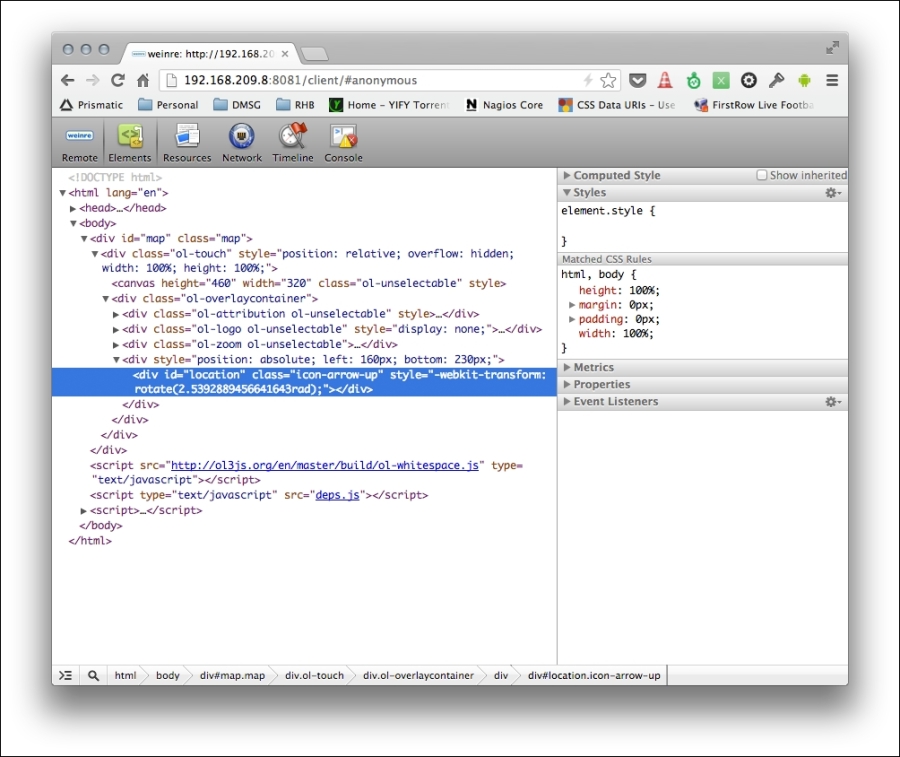

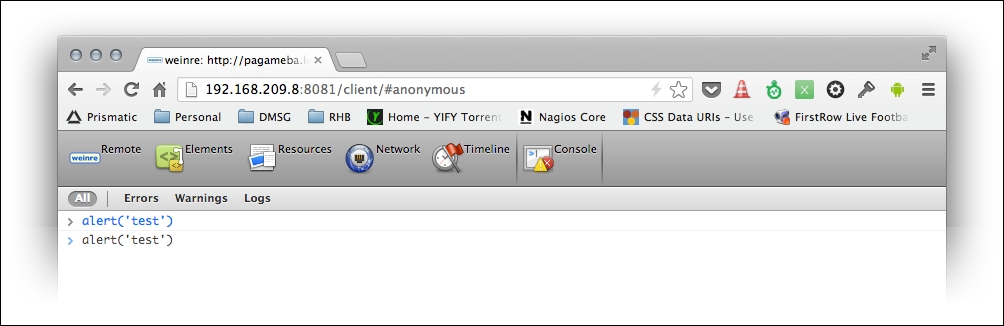

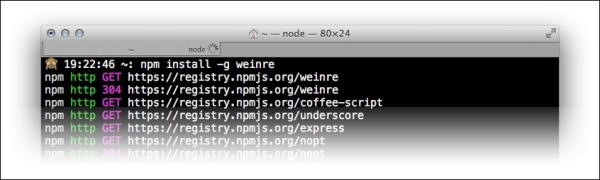

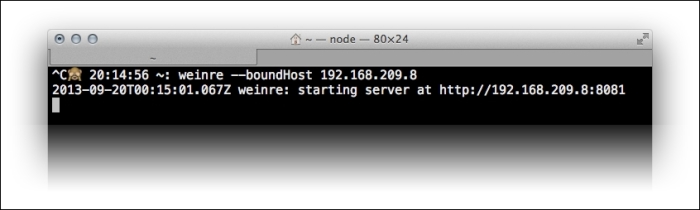

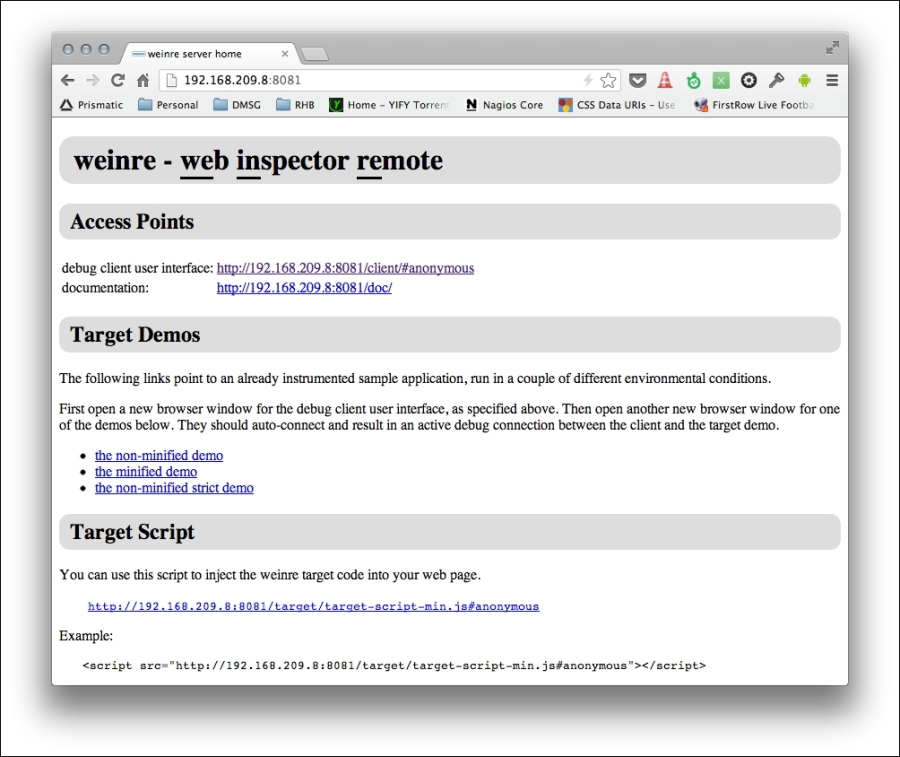

weinre –boundHost <your ip address>

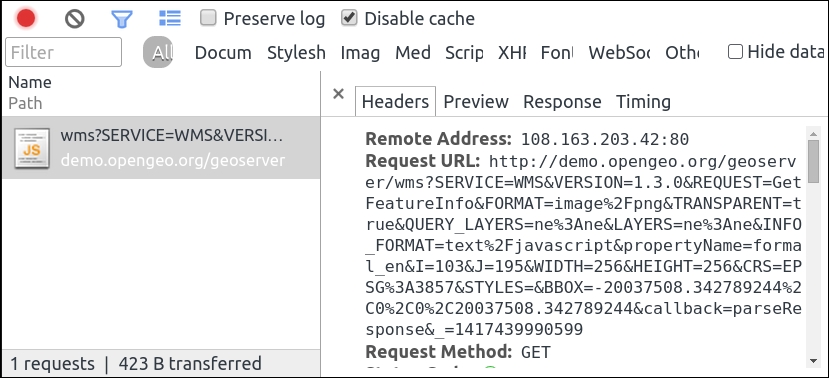

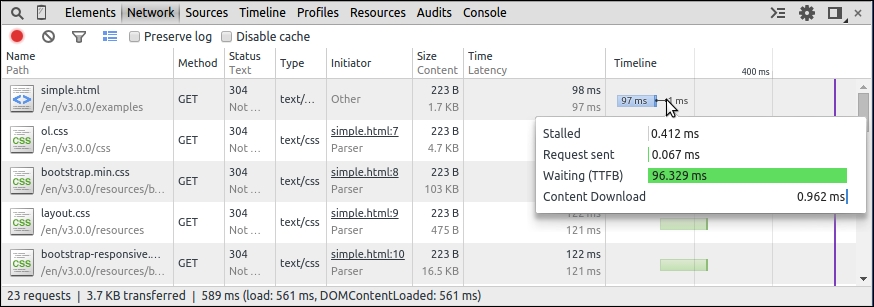

New terms and important words are shown in bold. Words that you see on the screen, in menus or dialog boxes for example, appear in the text like this: "You can do this in several ways but the easiest is to load your page into a web browser and look at the Network tab".

Feedback from our readers is always welcome. Let us know what you think about this book—what you liked or may have disliked. Reader feedback is important for us to develop titles that you really get the most out of.

To send us general feedback, simply send an e-mail to <feedback@packtpub.com>, and mention the book title via the subject of your message.

If there is a topic that you have expertise in and you are interested in either writing or contributing to a book, see our author guide on www.packtpub.com/authors.

Now that you are the proud owner of a Packt book, we have a number of things to help you to get the most from your purchase.

You can download the example code files for all Packt books you have purchased from your account at http://www.packtpub.com. If you purchased this book elsewhere, you can visit http://www.packtpub.com/support and register to have the files e-mailed directly to you.

We also provide you a PDF file that has color images of the screenshots/diagrams used in this book. The color images will help you better understand the changes in the output. You can download this file from: http://www.packtpub.com/sites/default/files/downloads/B02497_ColorImages.pdf

Although we have taken every care to ensure the accuracy of our content, mistakes do happen. If you find a mistake in one of our books—maybe a mistake in the text or the code—we would be grateful if you would report this to us. By doing so, you can save other readers from frustration and help us improve subsequent versions of this book. If you find any errata, please report them by visiting http://www.packtpub.com/submit-errata, selecting your book, clicking on the errata submission form link, and entering the details of your errata. Once your errata are verified, your submission will be accepted and the errata will be uploaded on our website, or added to any list of existing errata, under the Errata section of that title. Any existing errata can be viewed by selecting your title from http://www.packtpub.com/support.

Piracy of copyright material on the Internet is an ongoing problem across all media. At Packt, we take the protection of our copyright and licenses very seriously. If you come across any illegal copies of our works, in any form, on the Internet, please provide us with the location address or website name immediately so that we can pursue a remedy.

Please contact us at <copyright@packtpub.com> with a link to the suspected pirated material.

We appreciate your help in protecting our authors, and our ability to bring you valuable content.

You can contact us at <questions@packtpub.com> if you are having a problem with any aspect of the book, and we will do our best to address it.

Within the past few years, the popularity of interactive web maps has exploded. In the past, creating interactive maps was reserved for large companies or experts with lots of money. But now, with the advent of free services such as Google and Bing Maps, online mapping is easily accessible to everyone. Today, with the right tools, anyone can easily create a web map with little or even no knowledge of geography, cartography, or programming.

Web maps are expected to be fast, accurate, and easy to use. Since they are online, they are expected to be accessible from anywhere on nearly any platform. There are only a few tools that fulfill all these expectations. OpenLayers is one such tool. It's free, open source, and very powerful. Providing both novice developers and seasoned GIS professionals with a robust library, OpenLayers makes it easy to create modern, fast, and interactive web-mapping applications for desktop and mobile.

In this chapter, we will:

OpenLayers is an open source, client-side JavaScript library for making interactive web maps, viewable in nearly any web browser. Since it is a client-side library, it requires no special server-side software or settings—you can use it without even downloading anything! Originally developed by MetaCarta as a response, in part, to Google Maps, the 2.x series of the library has grown into a mature, popular framework with many passionate developers and a very helpful community. At the time of writing, this version is still actively used and maintained, but this book will focus on the latest version, which is 3.0. For people wishing to switch to OpenLayers 3, particularly people already using the OpenLayers 2 series, the main reasons to change are:

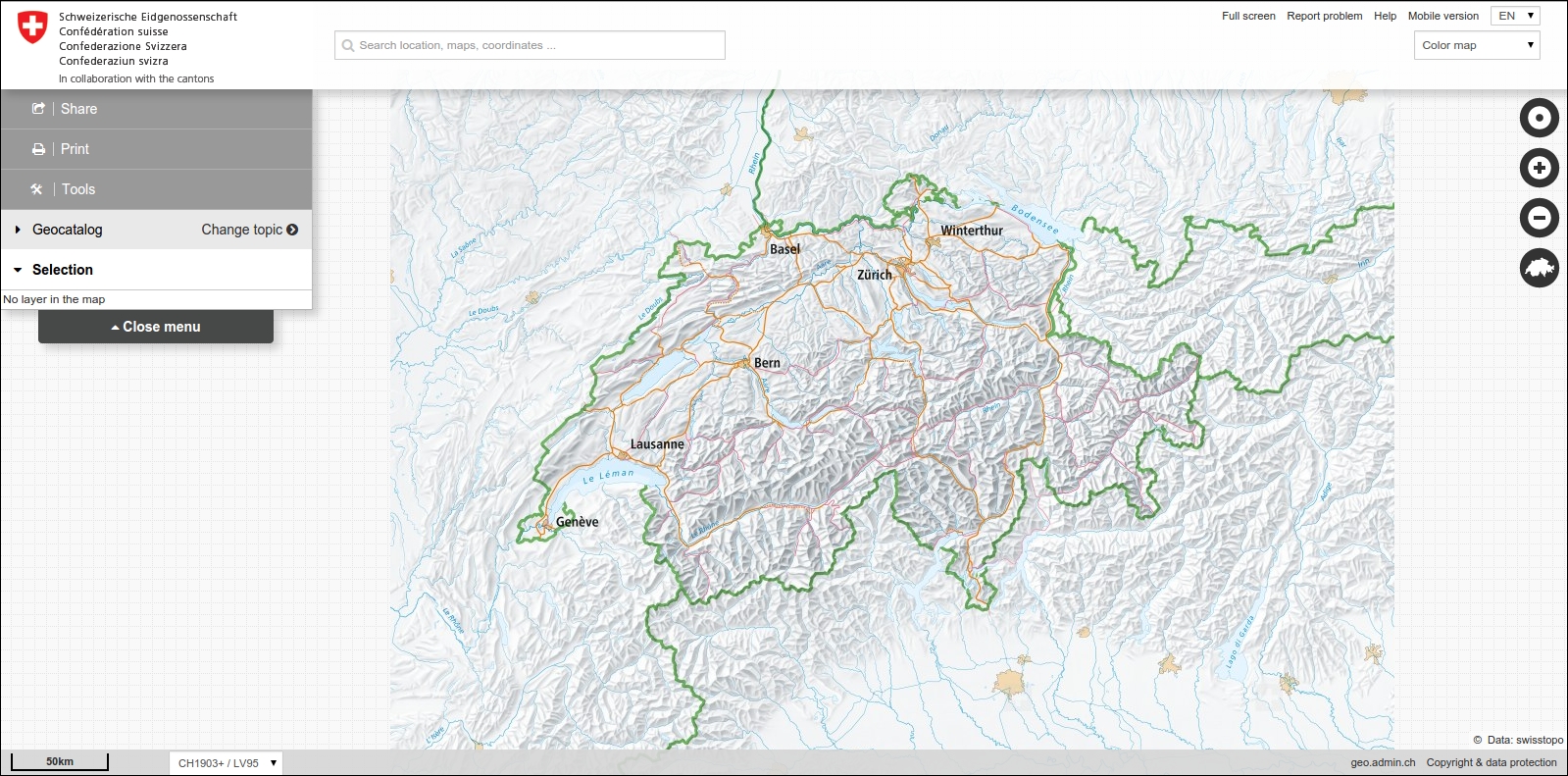

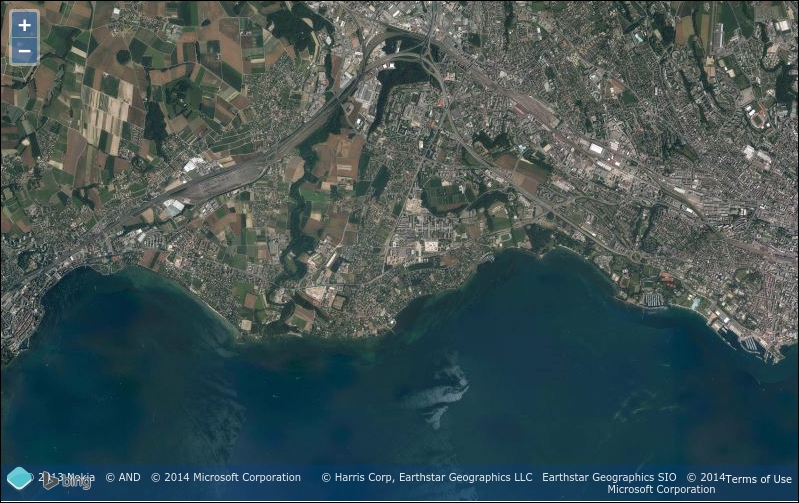

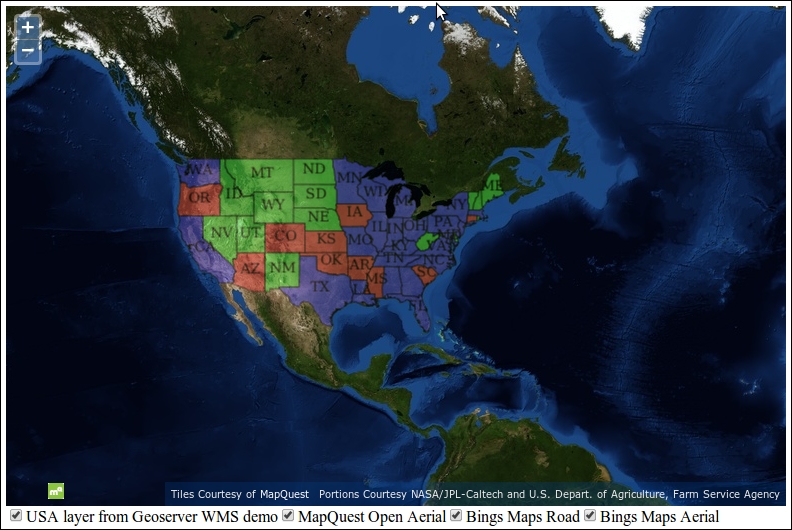

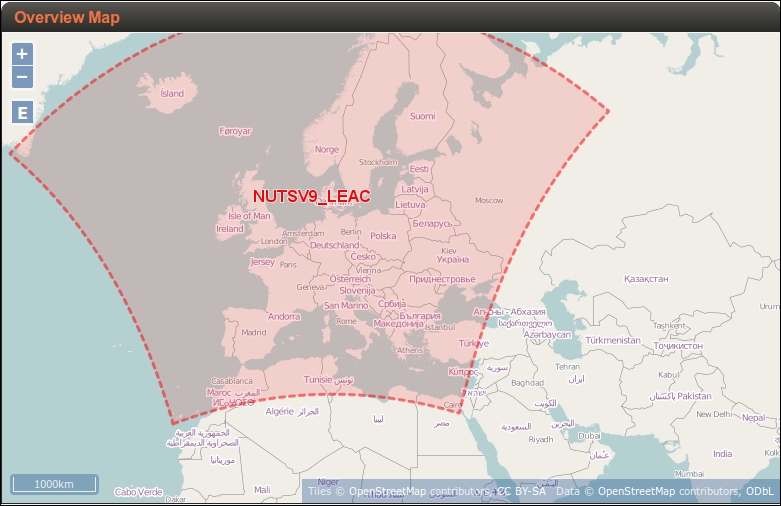

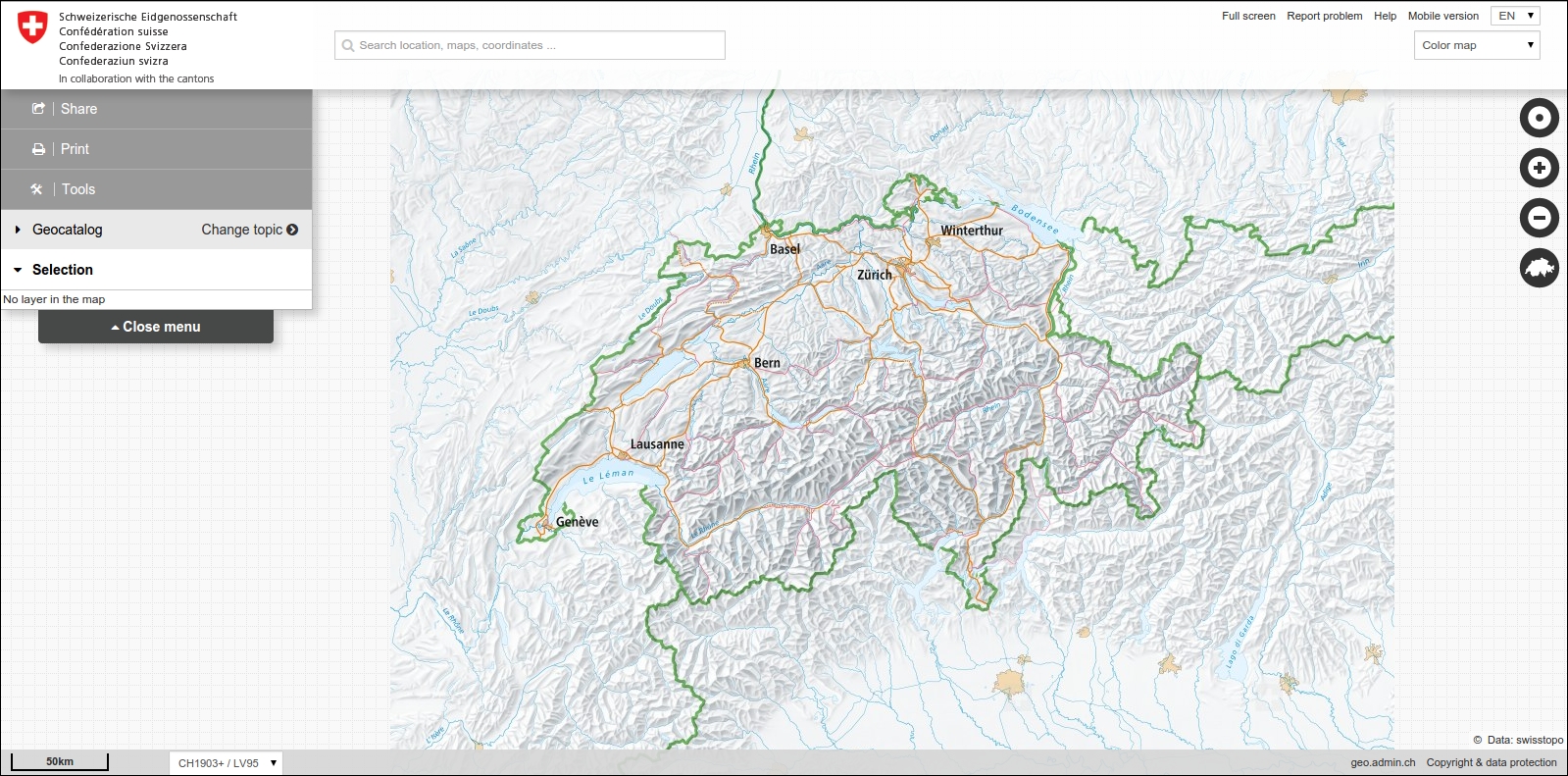

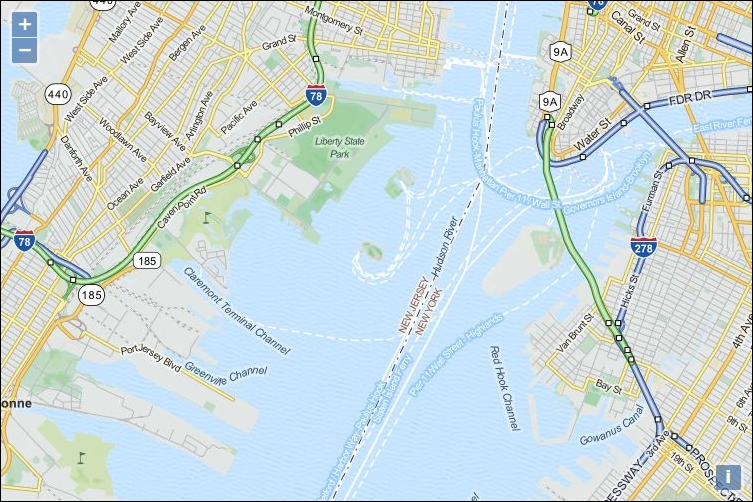

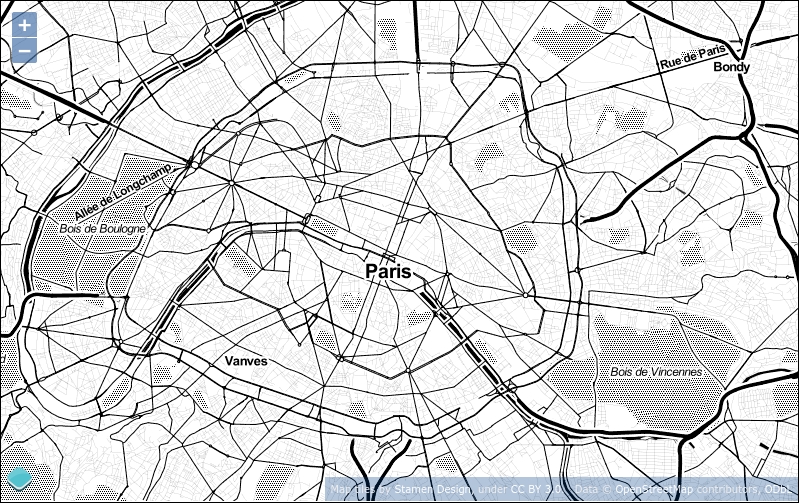

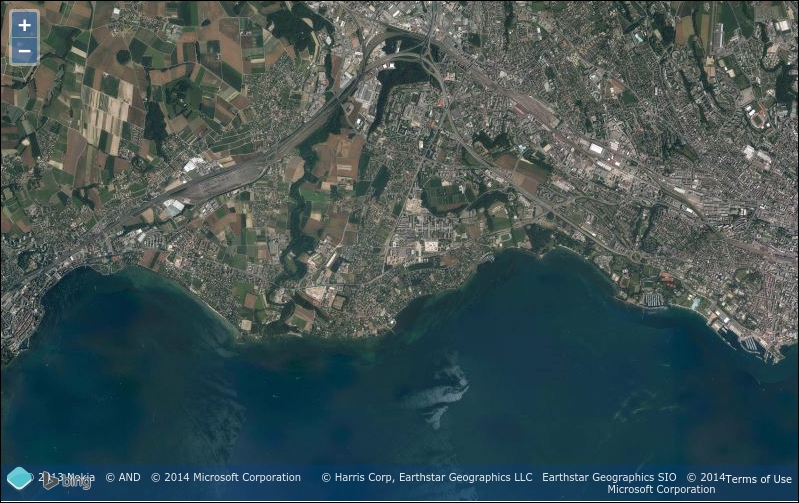

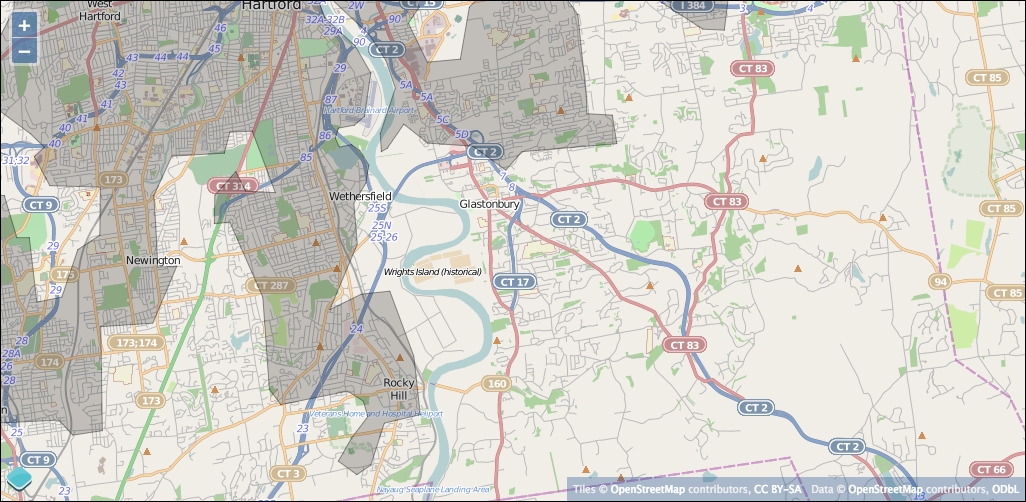

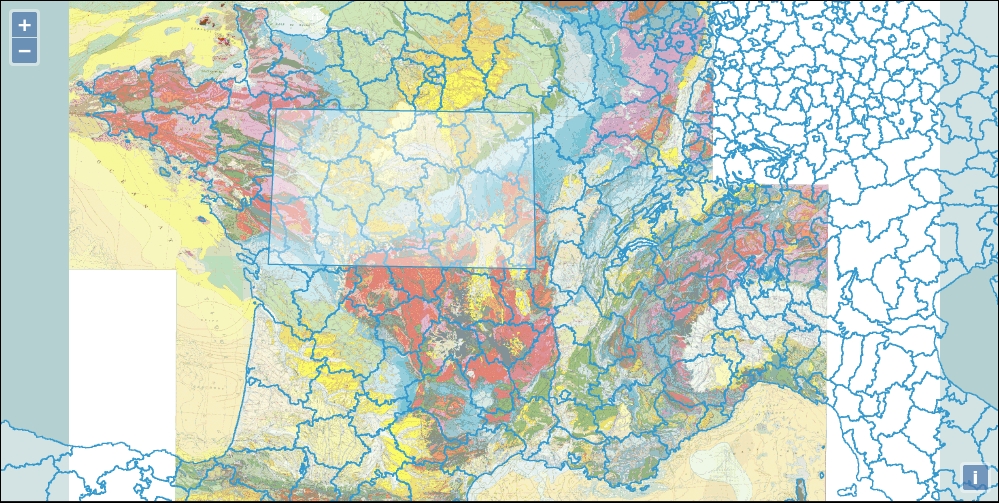

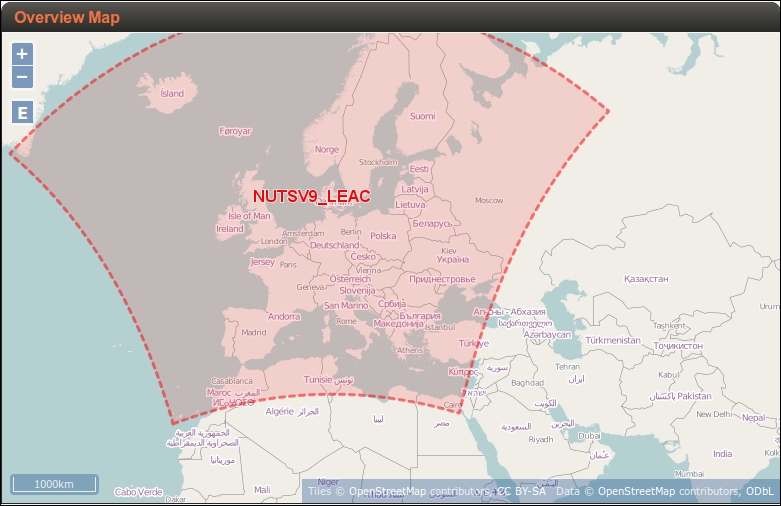

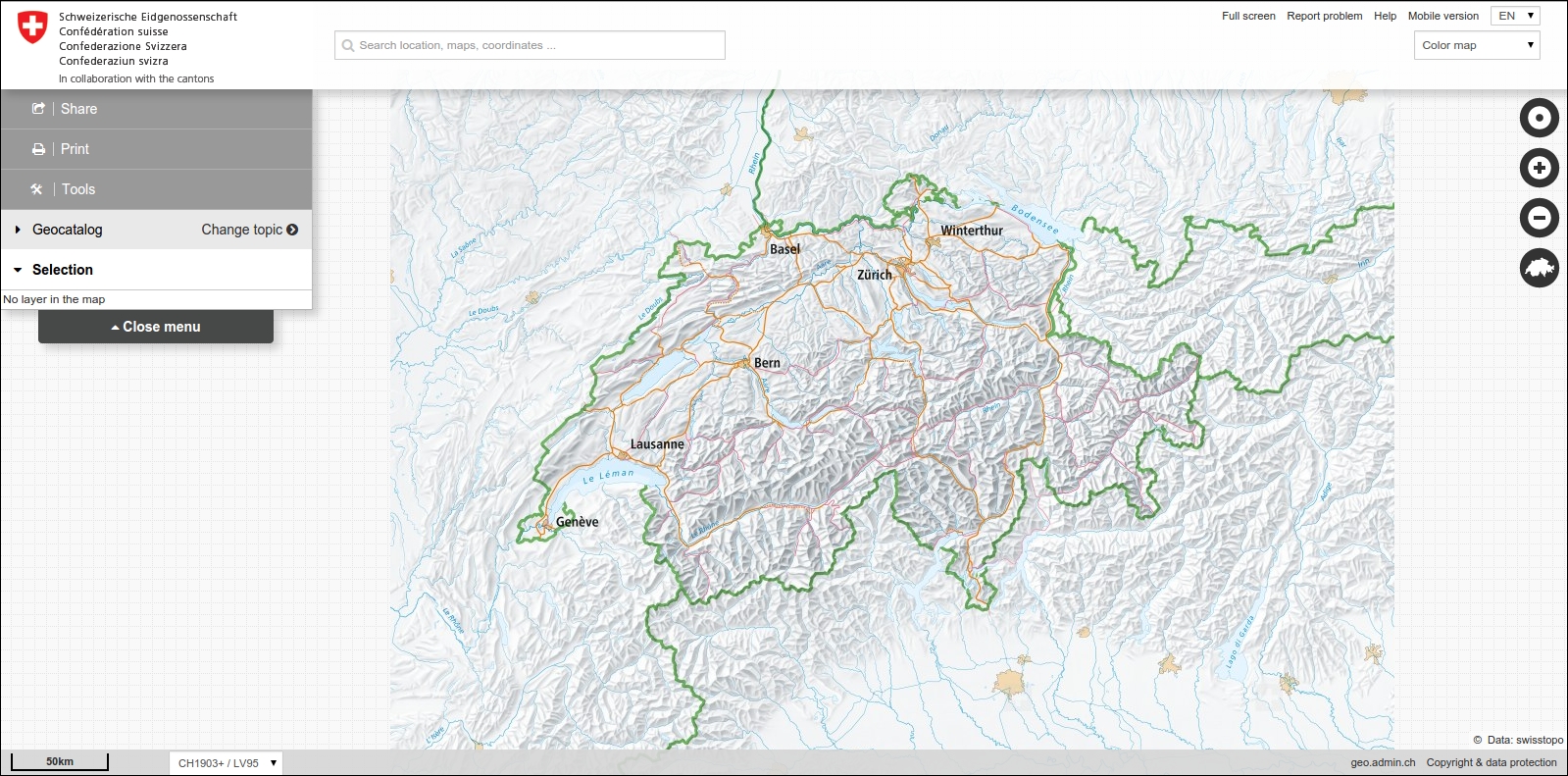

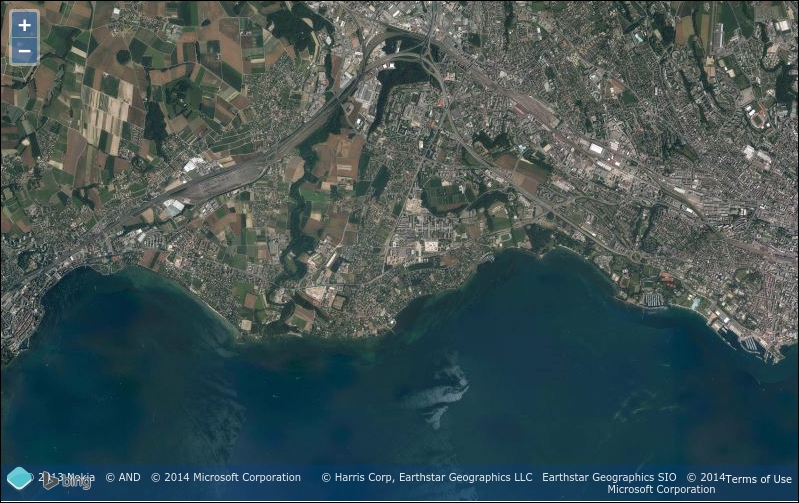

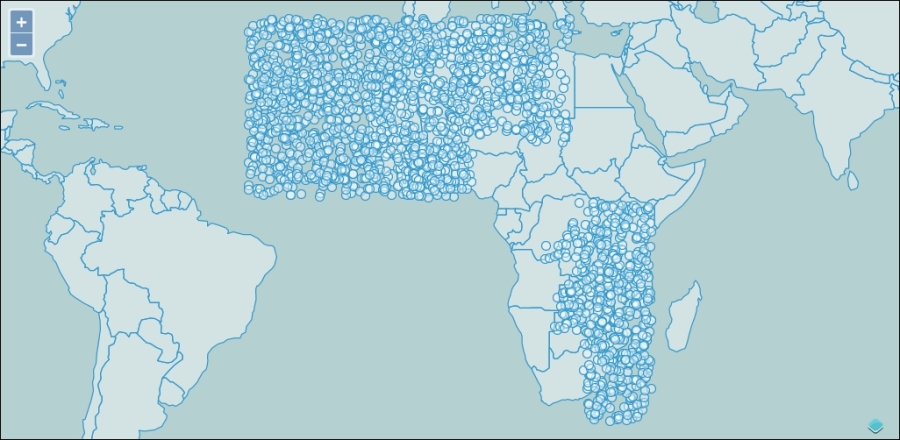

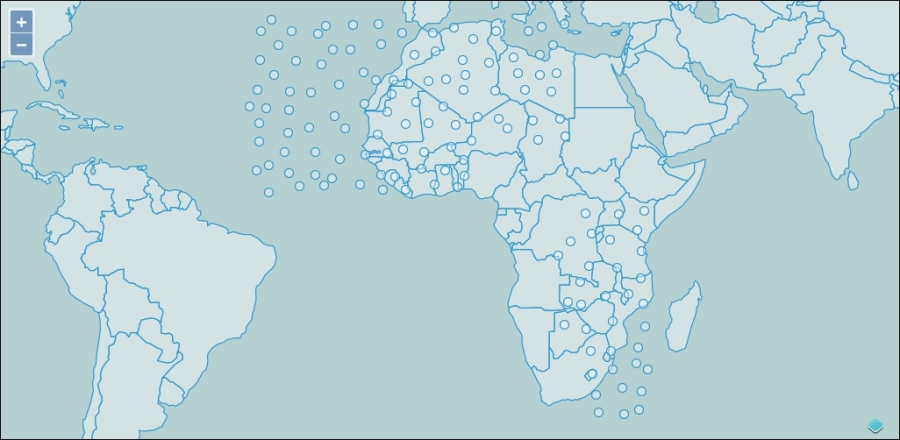

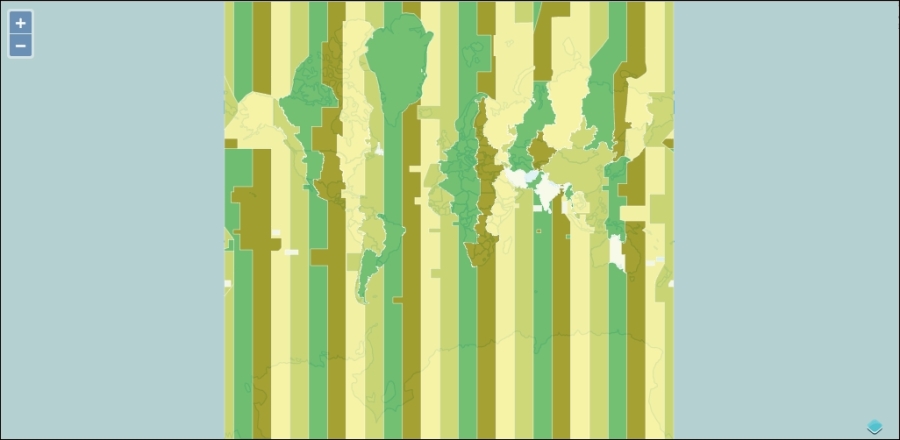

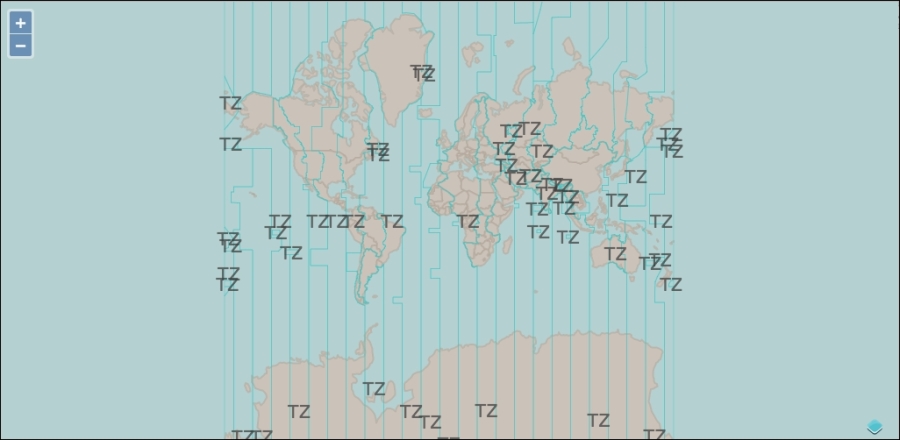

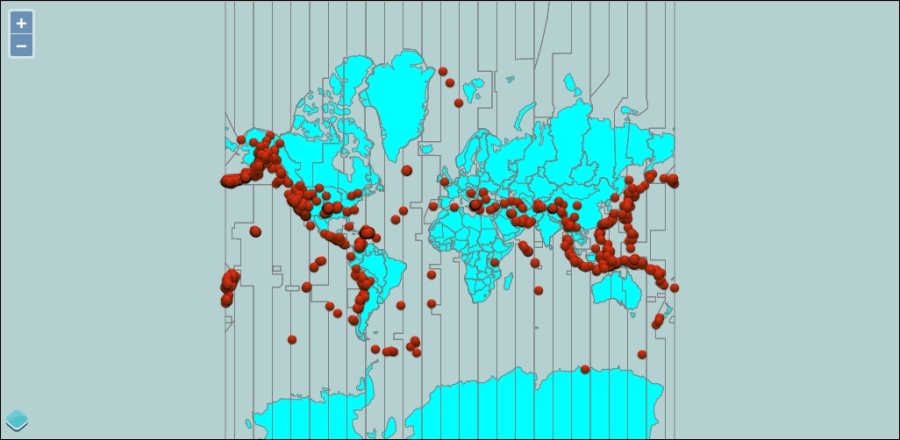

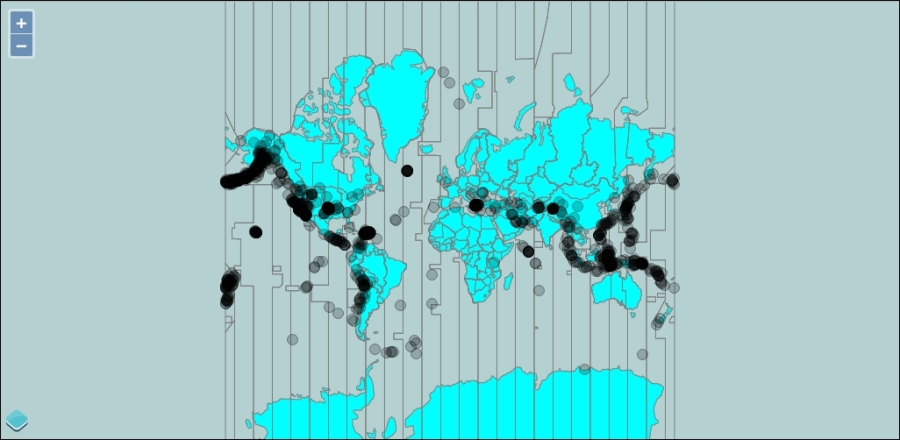

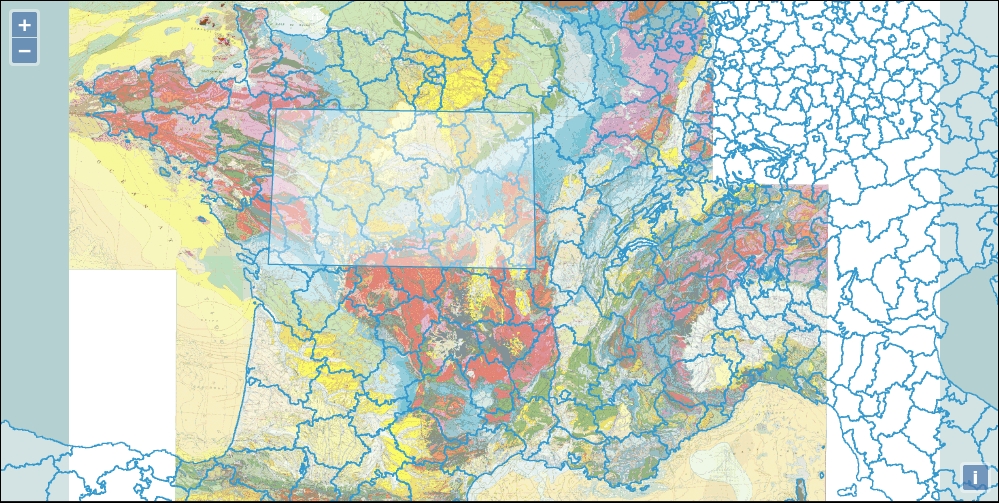

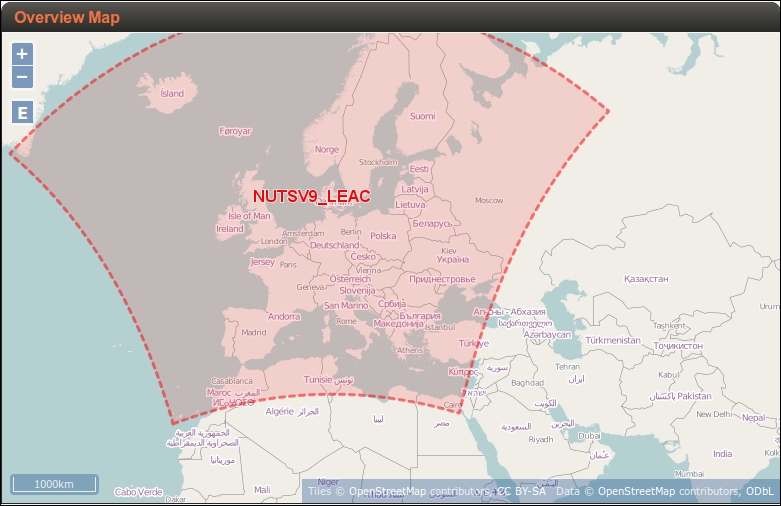

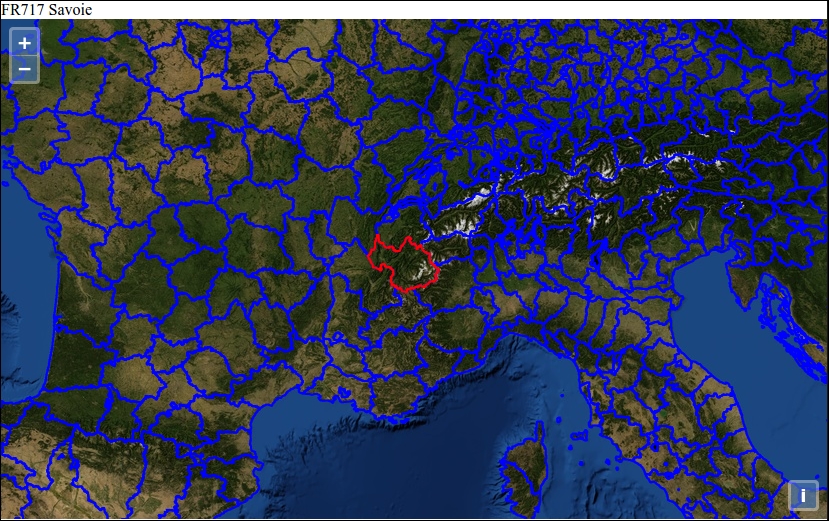

You can also add the fact that the library is already used in production, that demonstrates good performance at the Swiss federal geoportal, http://map.geo.admin.ch (see screenshot for reference ) and the OpenGeo Suite, a commercial open source based solution which already bundles the library:

OpenLayers makes creating powerful web mapping applications easy and fun. It is very simple to use—you don't even need to be a programmer to make a great map with it. It's open source, free, and has a strong community behind it. A big advantage of OpenLayers is that you can integrate it into any closed or open source application because it is released under the BSD 2-Clause license. So, if you want to dig into the internal code, or even improve it, you're encouraged to do so. Cross browser compatibility is handled for you by the Google Closure Library— but you need to have IE9+ because VML rendering (specific to IE8 and older versions) is no longer supported. Furthermore, OpenLayers 3.0 supports modern mobile, touch devices making it easy to develop for mobile technology.

OpenLayers is not tied to any proprietary technology or company, so you don't have to worry much about your application breaking with third party code (unless you break it). Although it's open source, you will get good support from the community and there are commercial support options as well. The library is recognized as well —established by the OSGeo (Open Source Geospatial Foundation), having passed through the OSGeo Incubation process, a kind of open source quality mark for geospatial projects.

You can read further about OSGeo Incubation at http://wiki.osgeo.org/wiki/Incubation_Committee

OpenLayers allows you to build entire mapping applications from the ground up, with the ability to customize every aspect of your map—layers, controls, events, and so on. You can use a multitude of different map server backends together, including a powerful vector layer. It makes creating map mashups extremely easy.

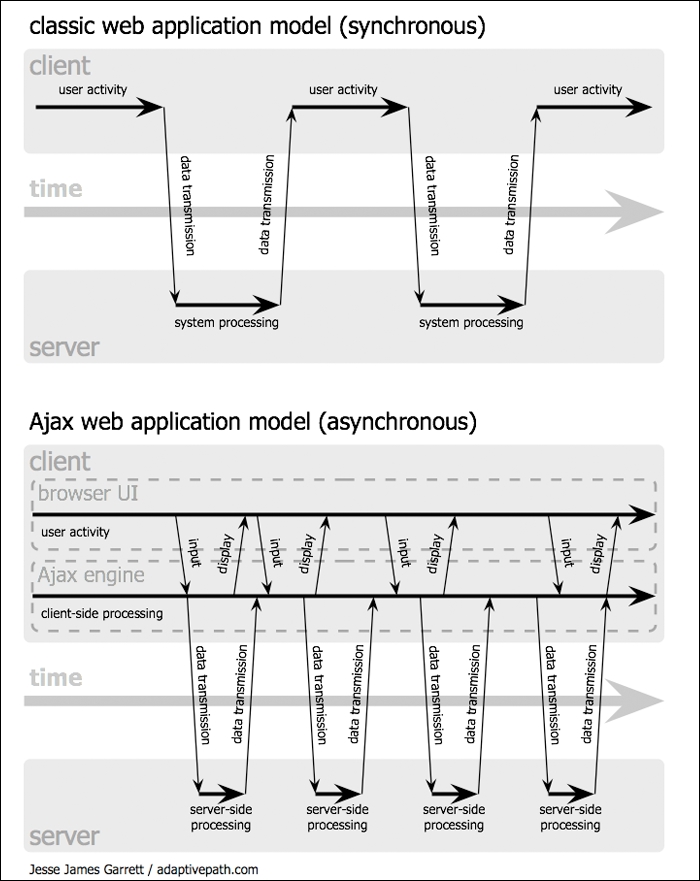

We said OpenLayers is a client-side JavaScript library, but what does this mean? The following context answers this question.

When we say client-side, we are referring to the user's computer, specifically their web browser. The only thing you need to make OpenLayers work is the OpenLayers code itself and a web browser. You can either download it and use it on your computer locally, or download nothing and simply link to the JavaScript file served on the site that hosts the OpenLayers project (http://openlayers.org). OpenLayers works on nearly all modern web browsers and can be served by any web server or your own computer. Using a modern, standard based browser such as Firefox, Google Chrome, Safari, or Opera is recommended.

When we say library, we mean that OpenLayers is a map engine that provides an API (Application Program Interface) that can be used to develop your own web maps. Instead of building a mapping application from scratch, you can use OpenLayers for the mapping part, which is maintained and developed by a bunch of brilliant people.

For example, if you'd want to write a blog, you could either write your own blog engine, or use an existing one such as WordPress or Drupal and build on top of it. Similarly, if you'd want to create a web map, you could either write your own from scratch, or use software that has been developed and tested by a group of developers with a strong community behind it.

By choosing to use OpenLayers, you do have to learn how to use the library (or else you wouldn't be reading this book), but the benefits greatly outweigh the costs. You get to use a rich, highly tested, and maintained code base, and all you have to do is learn how to use it. Hopefully, this book will help you with it.

OpenLayers is written in JavaScript, but don't fret if you don't know it very well. All you really need is some knowledge of the basic syntax, and we'll try to keep things as clear as possible in the code examples.

If you are unfamiliar with JavaScript, Mozilla provides phenomenal JavaScript documentation at https://developer.mozilla.org/en/javascript. We should also visit Eloquent JavaScript at http://eloquentjavascript.net, an online book to get started with the JavaScript language We recommend you also do some interactive exercises at Codecademy, http://codecademy.com, a website dedicated to learn JavaScript programming basics and much more.

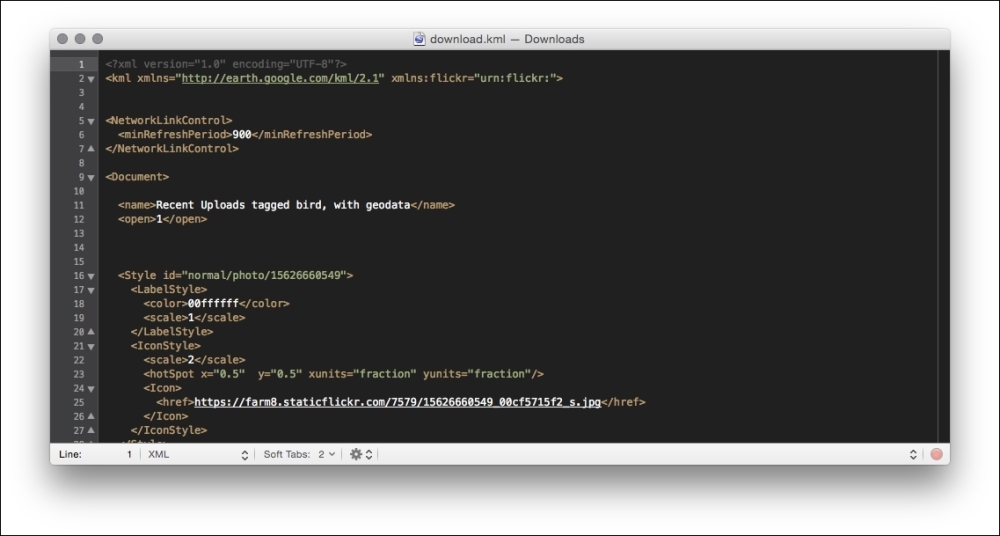

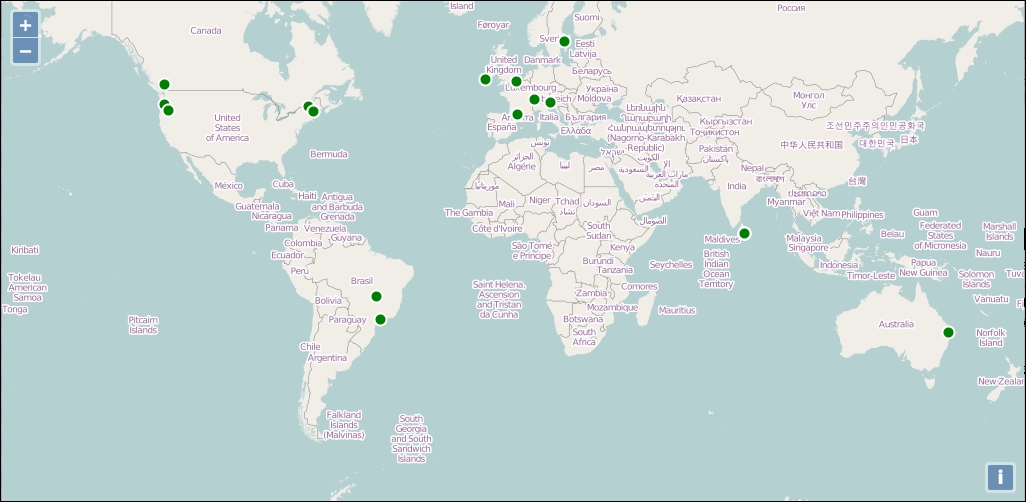

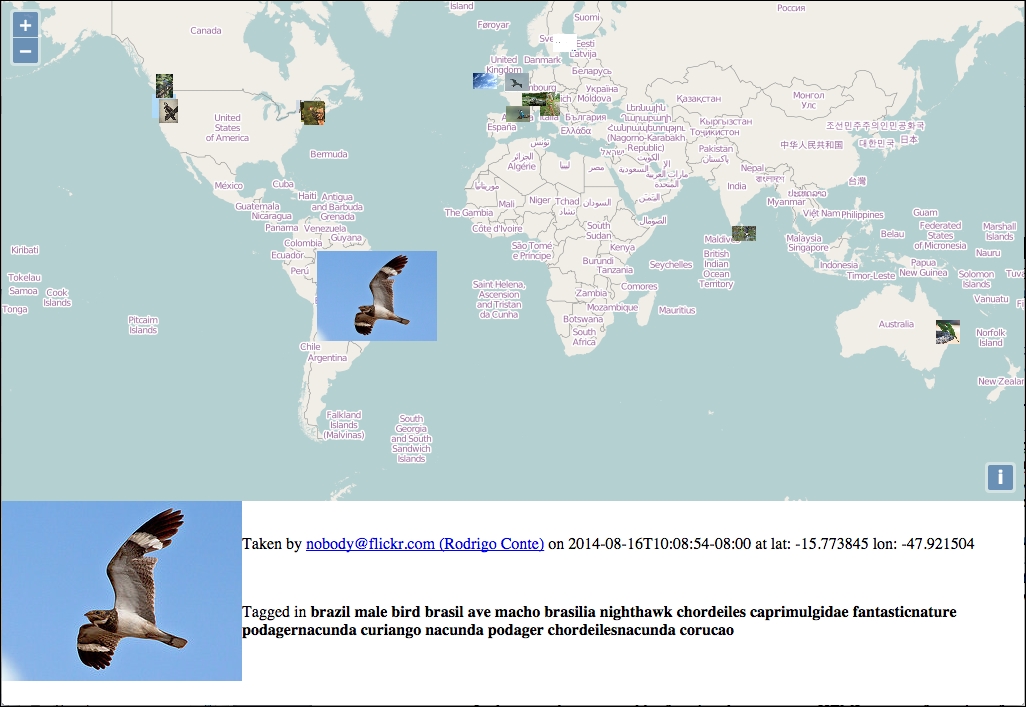

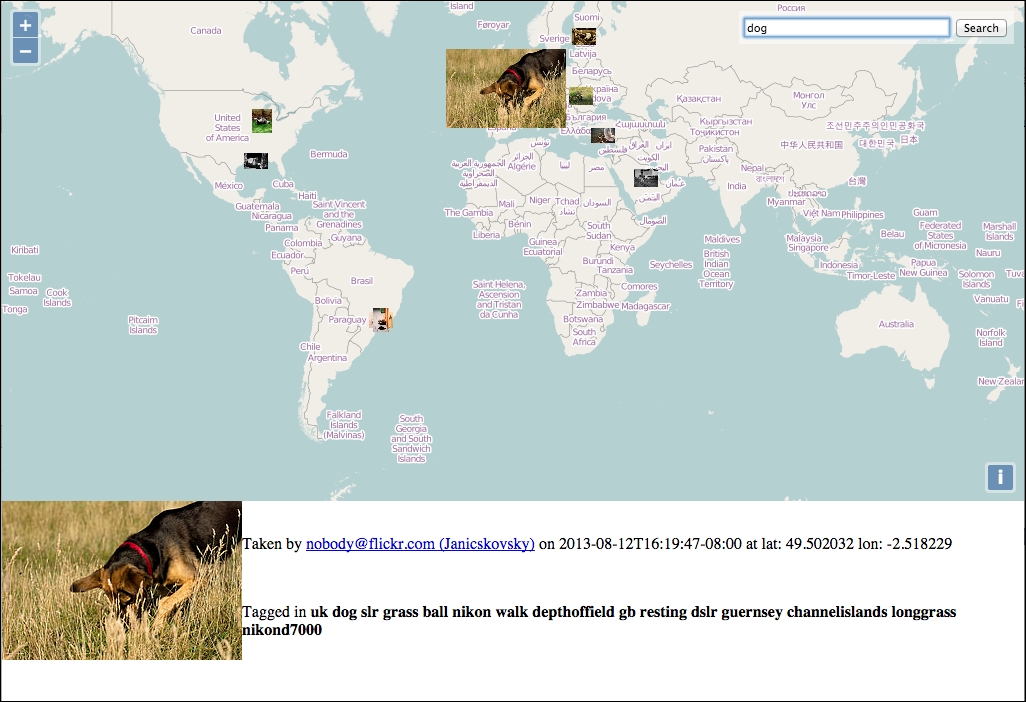

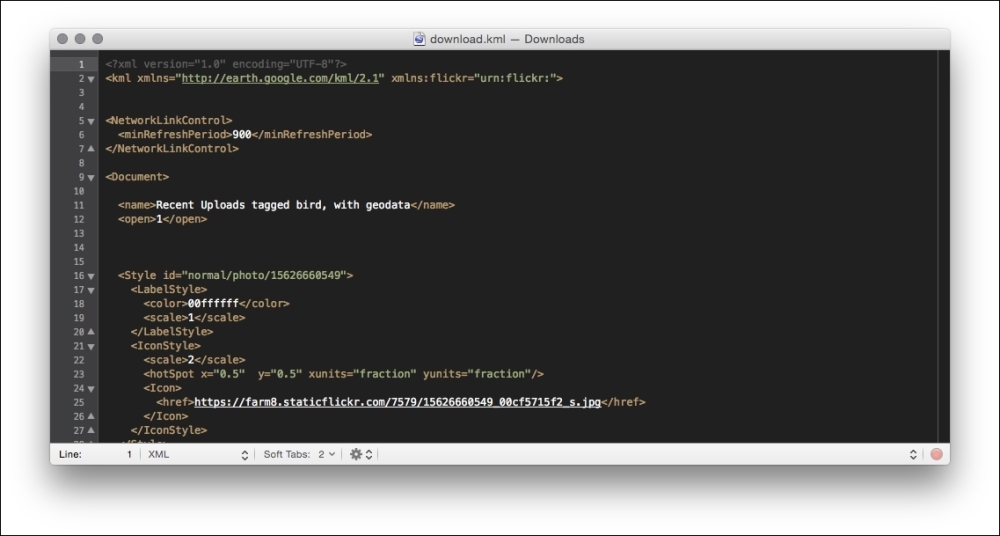

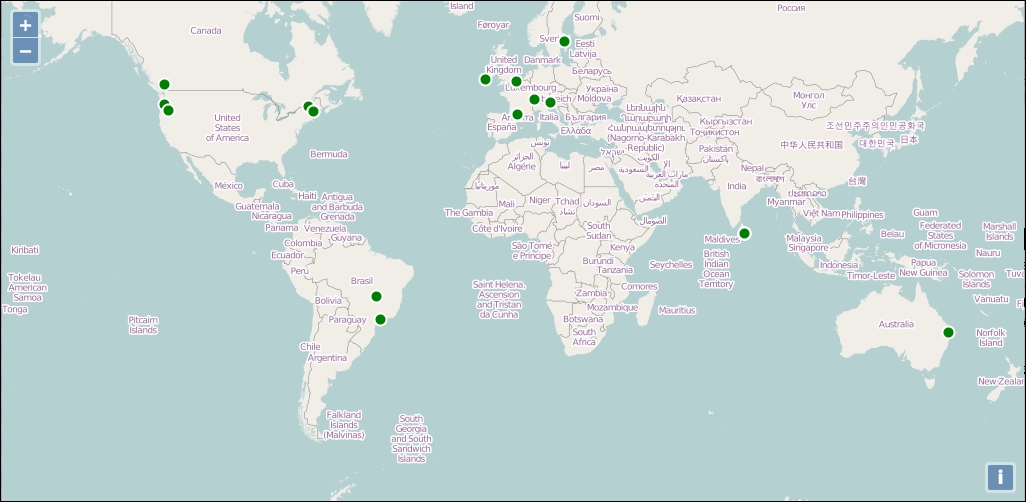

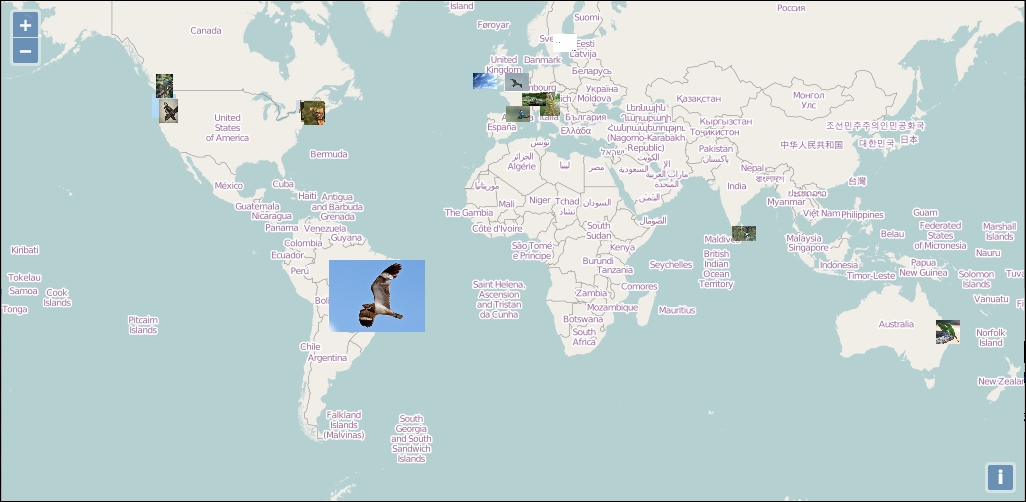

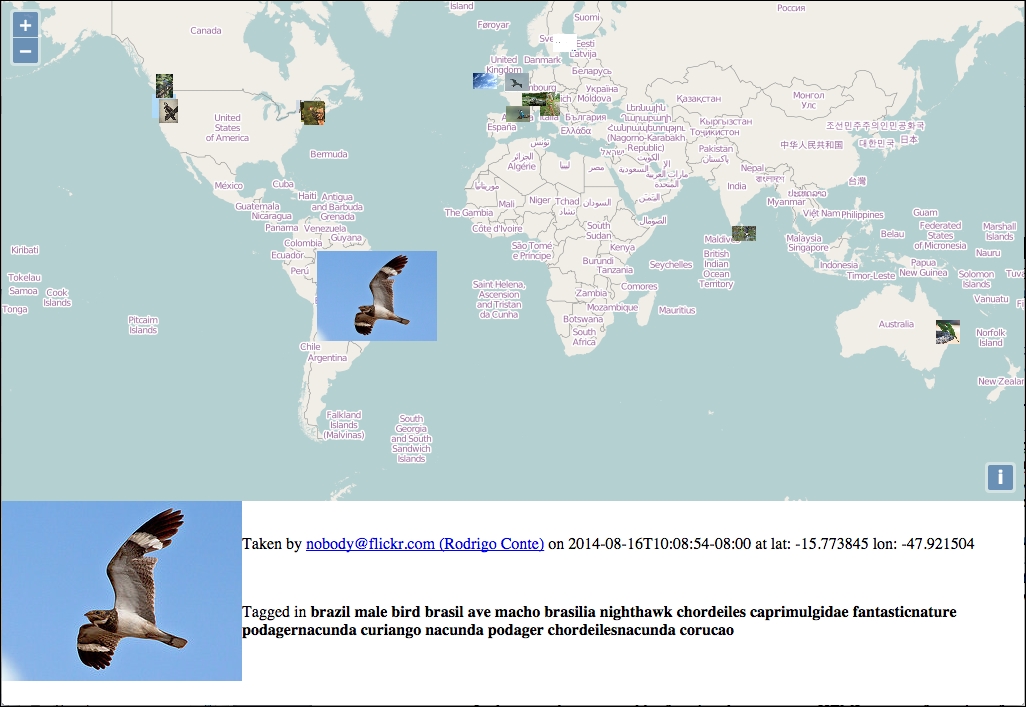

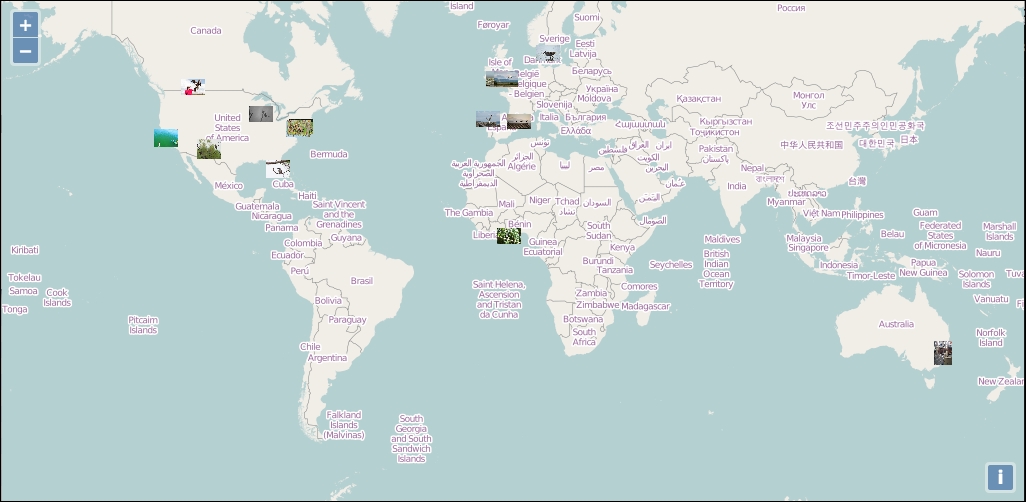

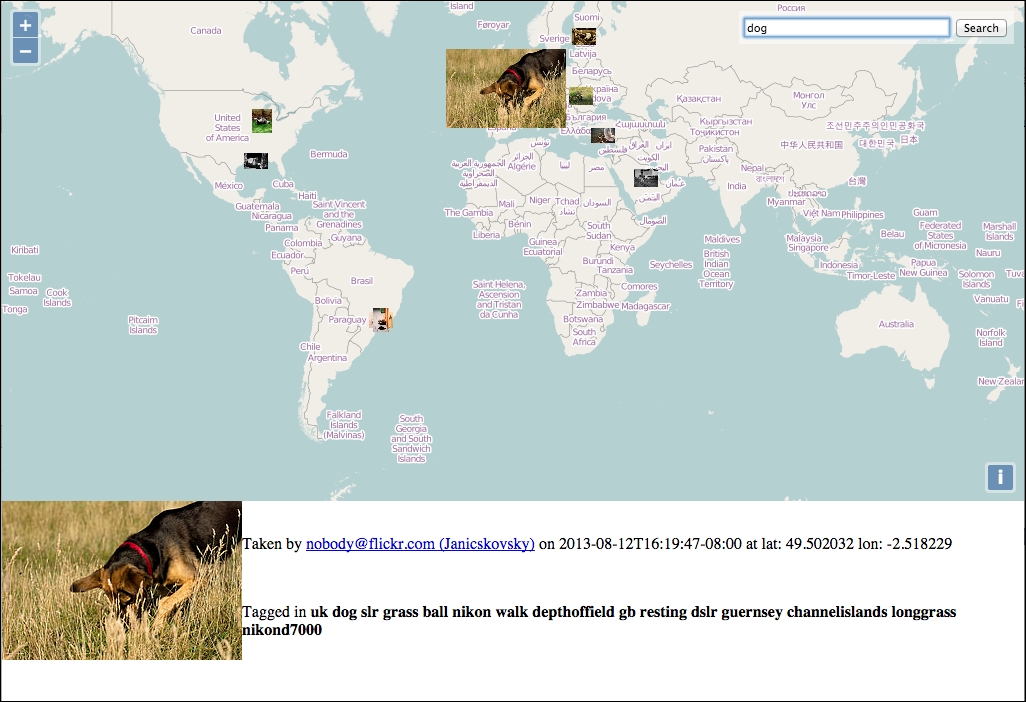

First off, what is a web-mapping application? To put it bluntly, it's some type of Internet application that makes use of a map. This could be a site that displays the latest geo-tagged images from Flickr (we'll do this in Chapter 11, Creating Web Map Apps), a map that shows markers of locations you've traveled to, or an application that tracks invasive plant species and displays them. If it contains a map and it does something, you could argue that it is a web map application. The term can be used in a pretty broad sense.

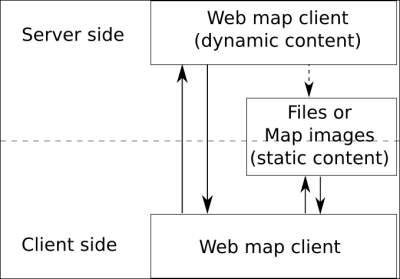

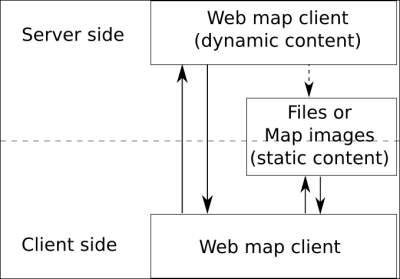

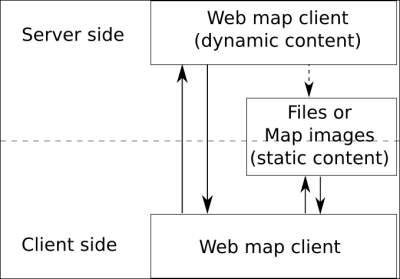

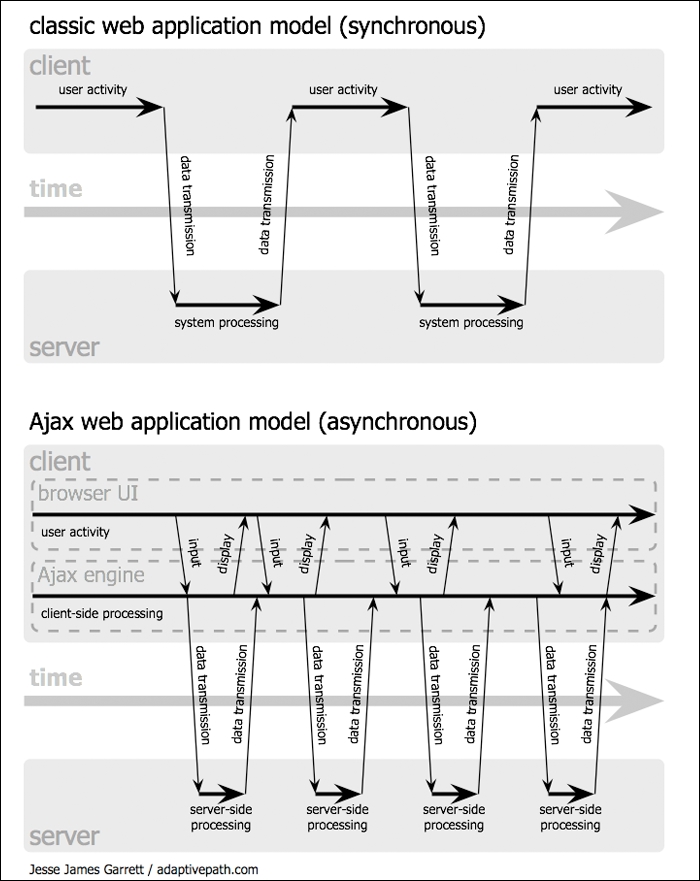

So, where exactly does OpenLayers fit in? We know OpenLayers is a client-side mapping library, but what does that mean? Let's take a look at the following figure:

This is called the client/server model and it is, essentially, the core of how all web applications operate. In the case of a web map application, some sort of map client (for example: OpenLayers) communicates with some sort of web map server (for example: a map server using the WMS (Web Map Service) standard, an OpenStreetMap backend, or some satellite images). We've added a bit of complexity in it because the truth is that you can also rely only on client-side for web mapping applications using static content that you have pre-generated. To illustrate, you can use GeoJSON files, a JSON based format to display pins. For example, it is very useful for mobile content.

OpenLayers lives on the client-side. One of the primary tasks the client performs is to get map images from a map server. Essentially, the client asks a map server for what you want to look at. Every time you navigate or zoom around on the map, the client has to make new requests to the server—because you're asking to look at something different.

OpenLayers handles this all for you, and it is happening via AJAX (asynchronous JavaScript + XML) calls to a map server. Refer to http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ajax_(programming) for further information on AJAX. To reiterate—the basic concept is that OpenLayers sends requests to a map server for map data every time you interact with the map, then OpenLayers pieces together all the returned map data (which might be images or vector data) so it looks like one big, seamless map. In Chapter 2, Key Concepts in OpenLayers, we'll cover this concept in more depth.

A map server (or map service) provides the map itself. There are a myriad of different map server backends. The examples include:

If you are unfamiliar with these terms, don't sweat it. The basic principle behind all these services is that they allow you to specify the area of the map you want to look at (by sending a request), and then the map servers send back a response containing the map image. With OpenLayers, you can choose to use as many different backends in any sort of combination as you'd like.

OpenLayers is not a web map server; it only consumes data from them. So, you will need access to some type of WMS. Don't worry about it though. Fortunately, there are a myriad of free and/or open source web map servers available that are remotely hosted or easy to set up yourself, such as MapServer. We speak a lot about web map servers but you must be aware that depending on your web-mapping application, you can use geographic data files to provide the needed data consumed by OpenLayers.

Throughout this book, we'll often use a freely available web-mapping service from http://www.openstreetmap.org/, so don't worry now about having to provide your own.

With many web map servers, you do not have to do anything to use them—just supplying a URL to them in OpenLayers is enough. OSGeo, OpenStreetMap, Google, Here Maps, and Bing Maps, for instance, provide access to their map servers (although some commercial restrictions may apply with various services in some situations).

The Google, Yahoo!, Bing, and ESRI's Mapping APIs allow you to connect with their map server backend. Their APIs also usually provide a client-side interface.

The Google Maps API, for instance, is fairly powerful. You have the ability to add markers, plot routes, and use KML data (things you can also do in OpenLayers)—but the main drawback is that your mapping application relies totally on Google. The map client and map server are provided by a third party. This is not inherently a bad thing, and for many projects, Google Maps and the others like it, are a good fit.

However, there are quite a few drawbacks such as:

Although we mentioned Google Maps API as one of the main maps, its support in OpenLayers is limited. As there are more tiles providers nowadays, it's not worth it to have code maintenance to support Google Maps API, a third party code that can break the main library, as sometimes happened earlier with the OpenLayers 2 API.

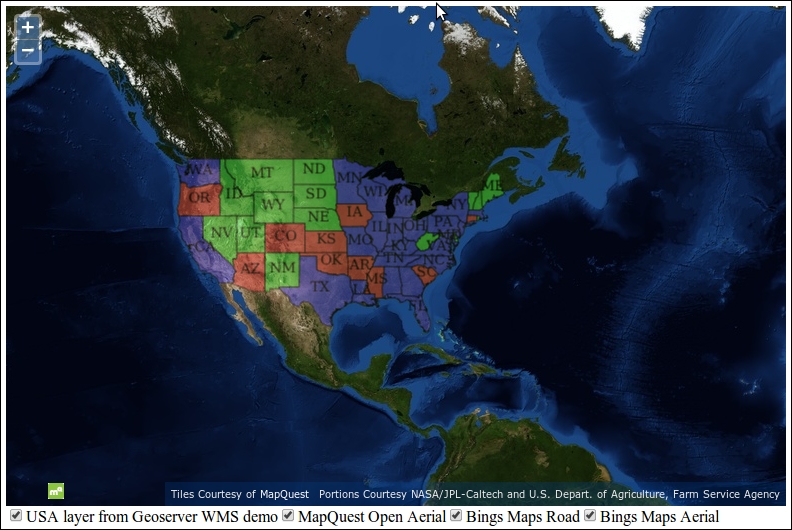

So, what's with the layers in OpenLayers? Well, OpenLayers allows you to have multiple different backend servers that your map can use. To access a web map server, you declare a layer and add it to your map with OpenLayers.

For instance, if you wanted to have a Bing Maps and an OpenStreetMap service displayed on your map, you would use OpenLayers to create a layer referencing Bing Maps and another one for OpenStreetMap, and then add them to your OpenLayers map. We'll soon see an example with an OpenStreetMap layer, so don't worry if you're a little confused.

Like layers of an onion, each layer is above and will cover up the previous one; the order that you add in the layers is important. With OpenLayers, you can arbitrarily set the overall transparency of any layer, so you are easily able to control how many layers cover each other up, and dynamically change the layer order at any time.

Most of the time, you make a distinction between base layers and non-base layers. Base layers are layers below the others and are used as a background on your maps to give general context. When you choose one base layer, the others will not be shown. On the top of base layers, you have non-base layers used to emphasize particular topics. You can also choose to use only overlay layers if you're considering that they are enough to understand the map. As a classical example, you could have a Bing map as your base layer, a layer with satellite imagery that is semi-transparent, and a vector layer, all active on your map at once. A vector layer is a powerful layer that allows for the addition of markers and various geometric objects to our maps—we'll cover it in Chapter 5, Using Vector Layers. Thus, in this example, your map would have three separate layers. We'll study in detail about layers and how to use and combine them in Chapter 4, Interacting with Raster Data Source.

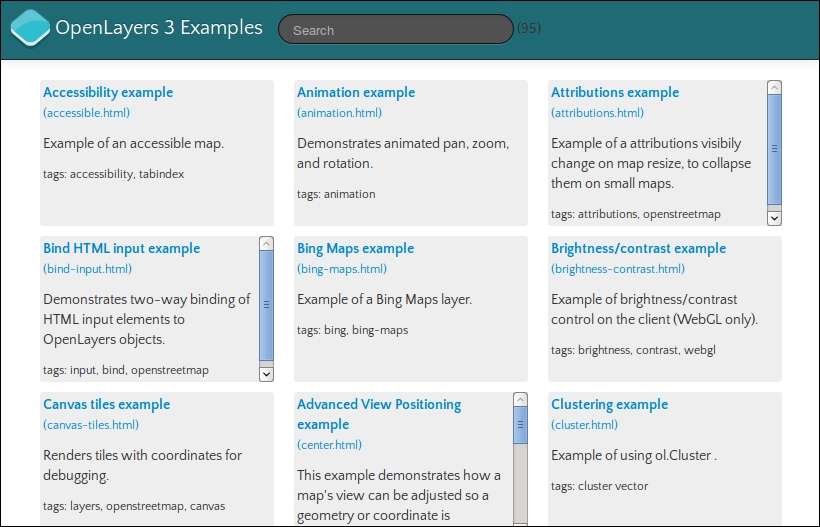

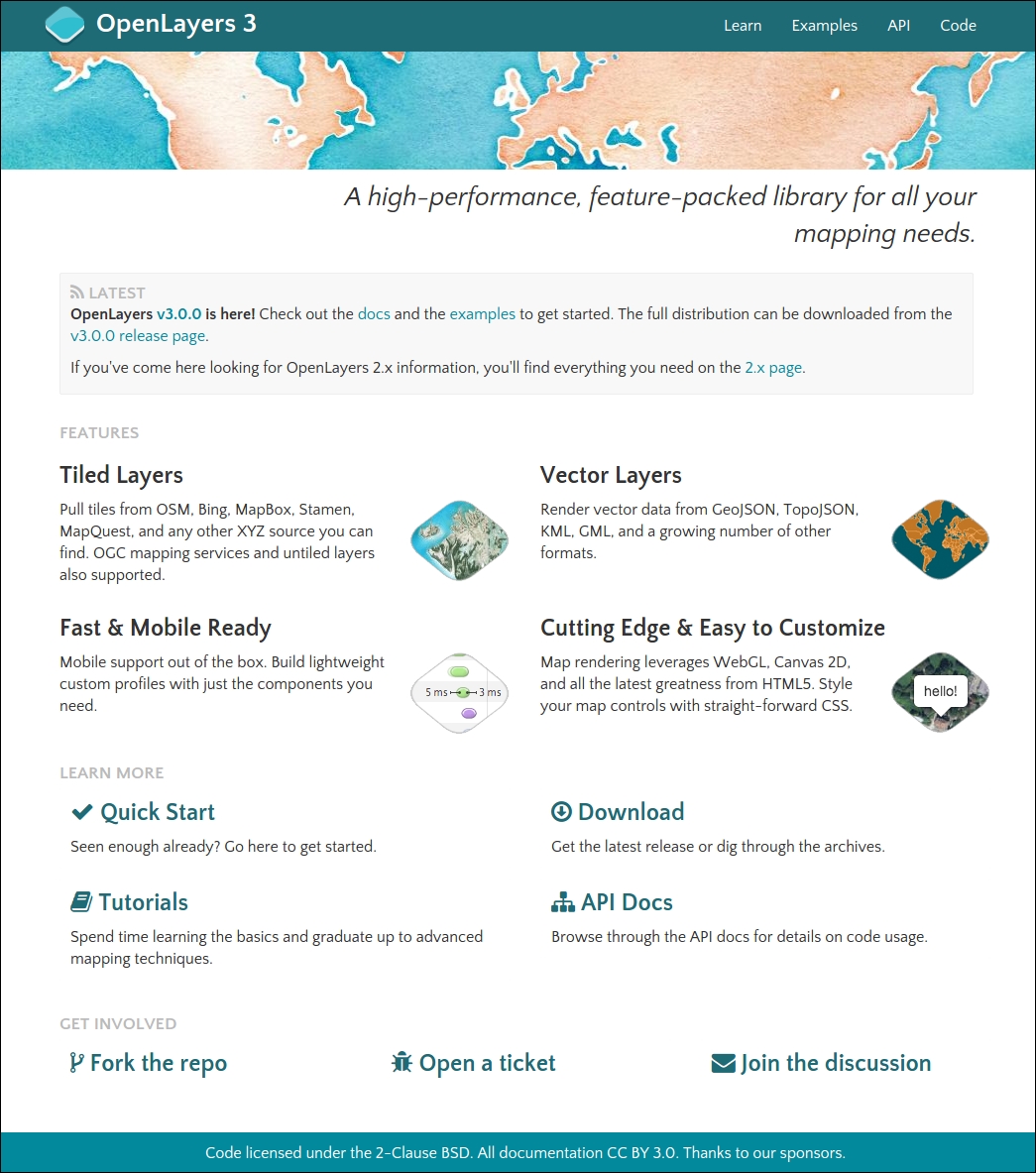

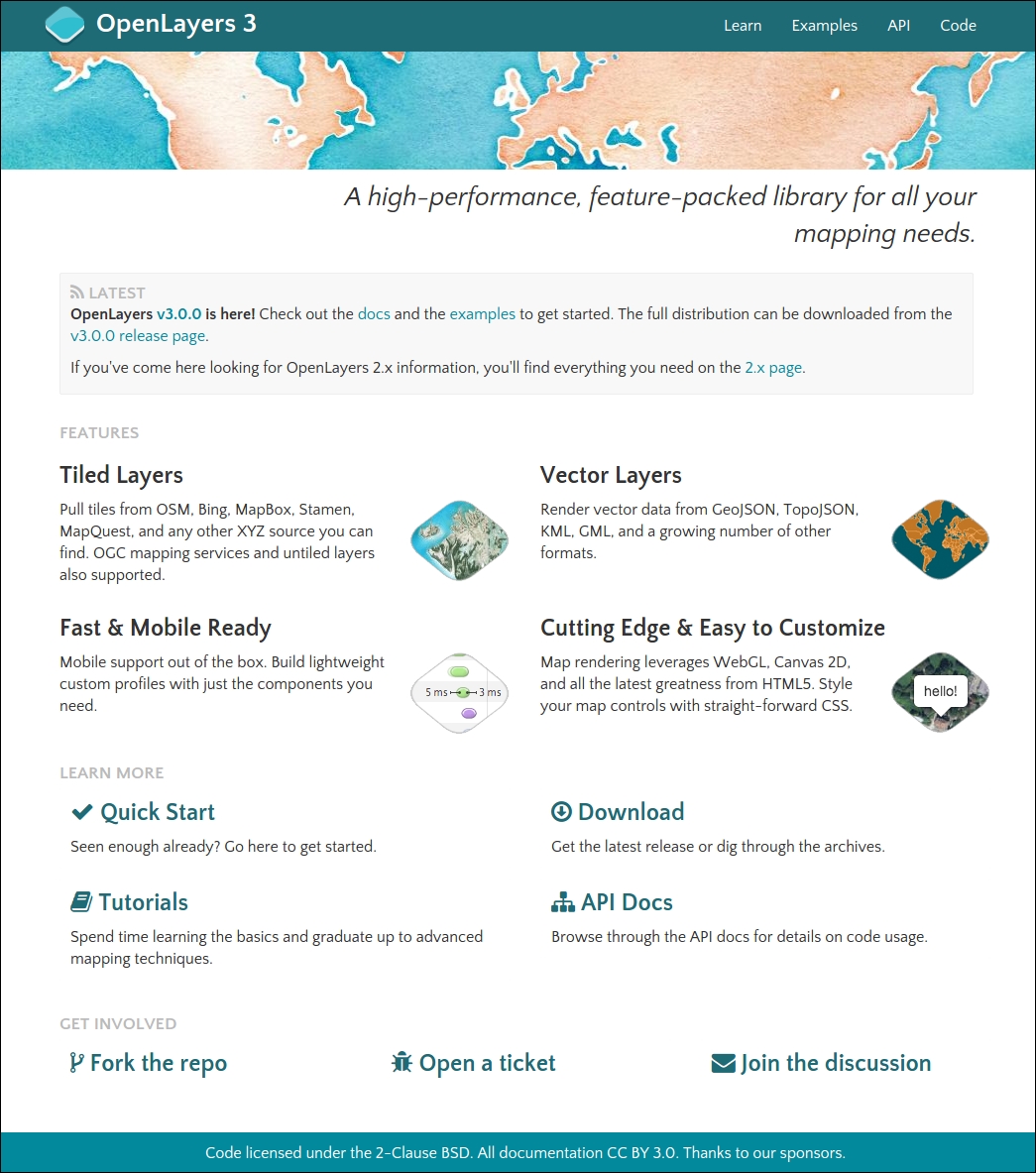

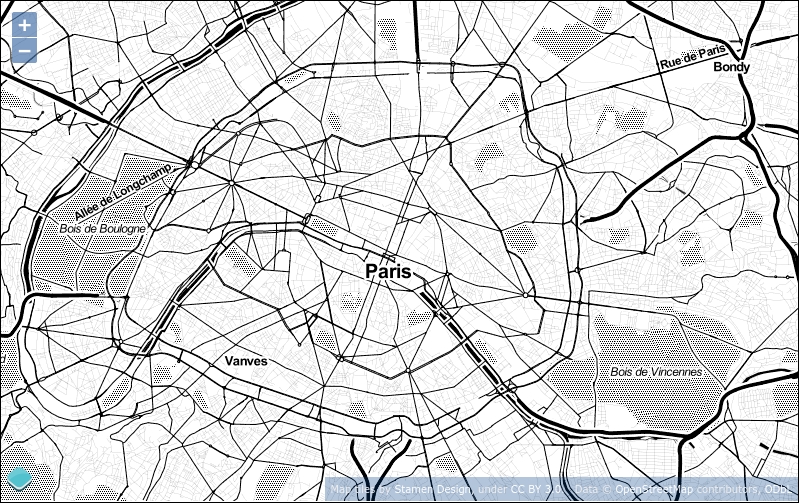

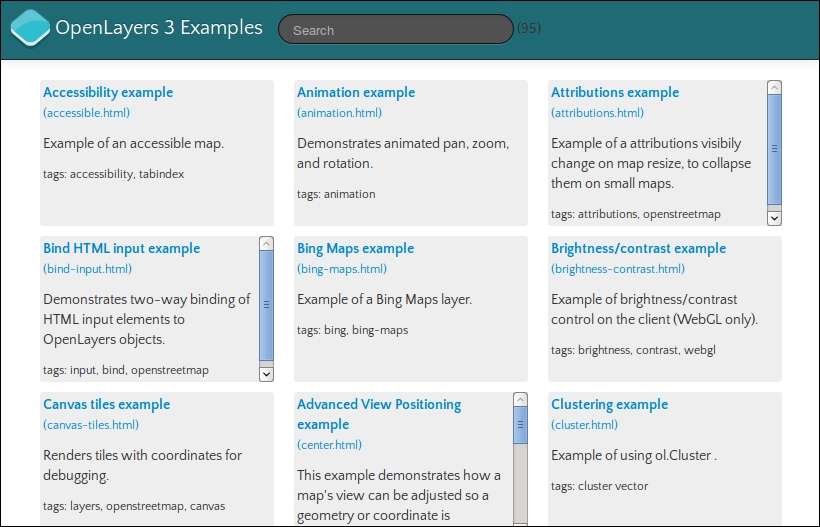

The website for OpenLayers 3 is located at http://openlayers.org. Have a look at the following screenshot:

To begin, you need to download a copy of OpenLayers (or we can directly link to the library—but we'll download a local copy). You can download the compressed library as a .zip by clicking on the green button at the bottom of the release page at https://github.com/openlayers/ol3/releases/tag/v3.0.0.

We will cover the website links by following the different areas of the main web page. Let's start with the navigation bar located at the top right area:

Be aware that currently both versions of OpenLayers exist

Let's download the OpenLayers library. After you're done, you should have the OpenLayers library files set up on your computer. Perform the following steps:

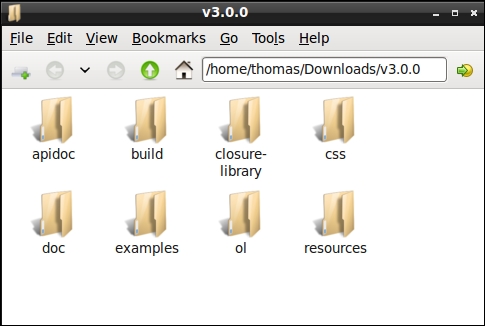

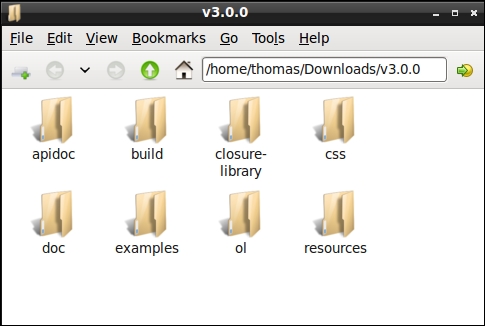

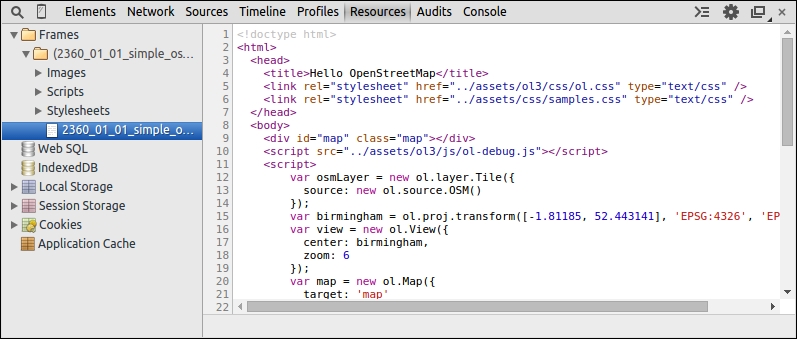

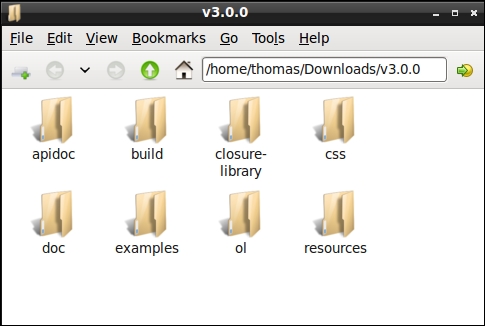

v3.0.0.zip version of the OpenLayers v3.0.0. It's the green button on the bottom left of the Github release page for v3.0.0.v3.0.0 (or whatever your version is).v3.0.0 folder. Once inside, you'll see a lot of folders, but the ones we are concerned with right now are the folders named build and css, as seen in the following screenshot:

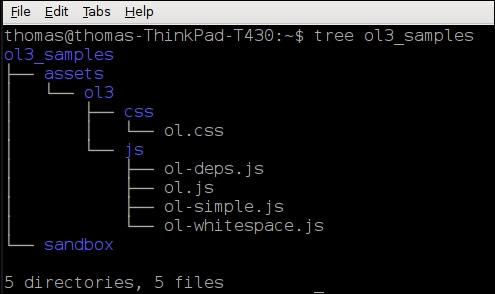

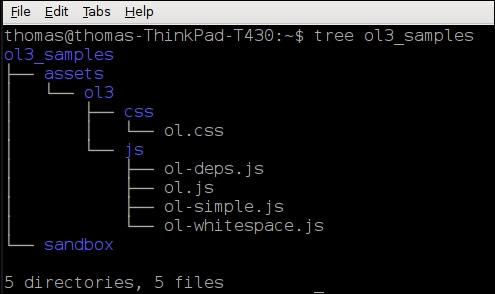

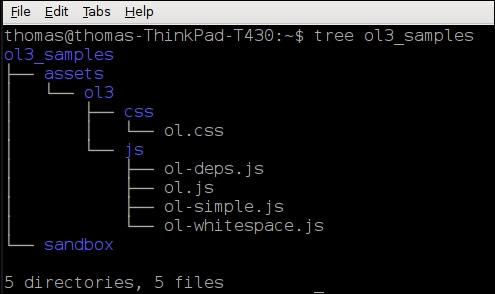

ol3 folder within an assets folder contained within a new folder ol3_samples in your home directory (or C:\ on Windows). Copy the previous build folder from v3.0.0 and rename it as js into the new ol3 directory and also copy the css folder into the same ol3 folder.sandbox into the ol3_samples directory. You can name the folder whatever you like, but we'll refer to it as the sandbox folder. Your new folder structure should look similar to the following screenshot:

We just installed OpenLayers 3 by copying over different pre-built, compressed JavaScript files containing the entire OpenLayers 3 library code (from the build directory) and the associated assets (style sheets). To use OpenLayers, you'll need at a minimum, the ol.js file (the other .js files will be needed during the book but are not always required) and the ol.css file. For best practice, we already gave you some tips to structure the code like separate assets, such as css and js, or separate library code from your own code.

If you open the ol.js file, you'll notice it is nearly unreadable. This is because this is a minified and obfuscated version, which basically means extra white space and unnecessary characters have been stripped out to cut down on the file size and some variables have been shortened whenever possible. While it is no longer readable, it is a bit smaller and thus requires less time to download. If you want to look at the uncompressed source code, you can view it by looking in the ol-debug.js file within the js folder of the ol3 directory.

You can, as we'll see in the last chapter of this book, build your own custom configurations of the library, including only the things you need. But for now, we'll just use the entire library. Now that we have our OpenLayers library files ready to use, let's make use of them!

The process for creating a map with OpenLayers requires, at a minimum, the following things:

ol.layer.* classol.Map class by adding a layerol.View class to set for the Map class (defining the area where the map will initially be displayed)Now, we're finally ready to create our first map!

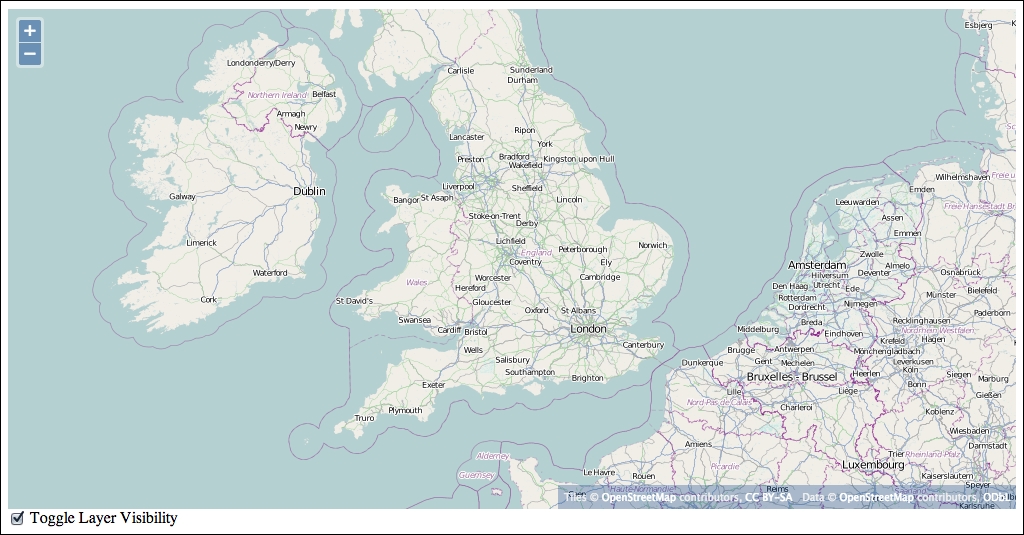

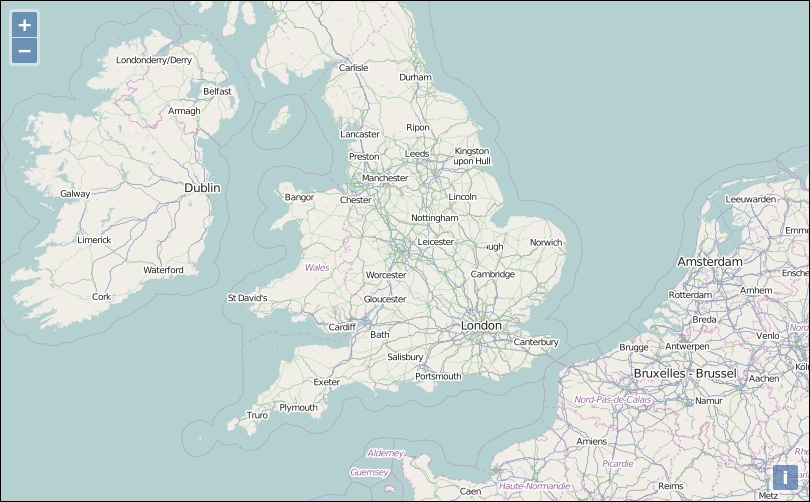

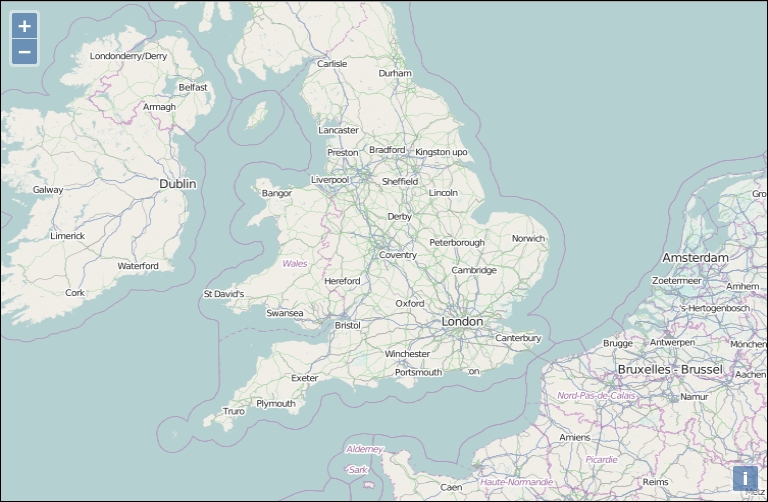

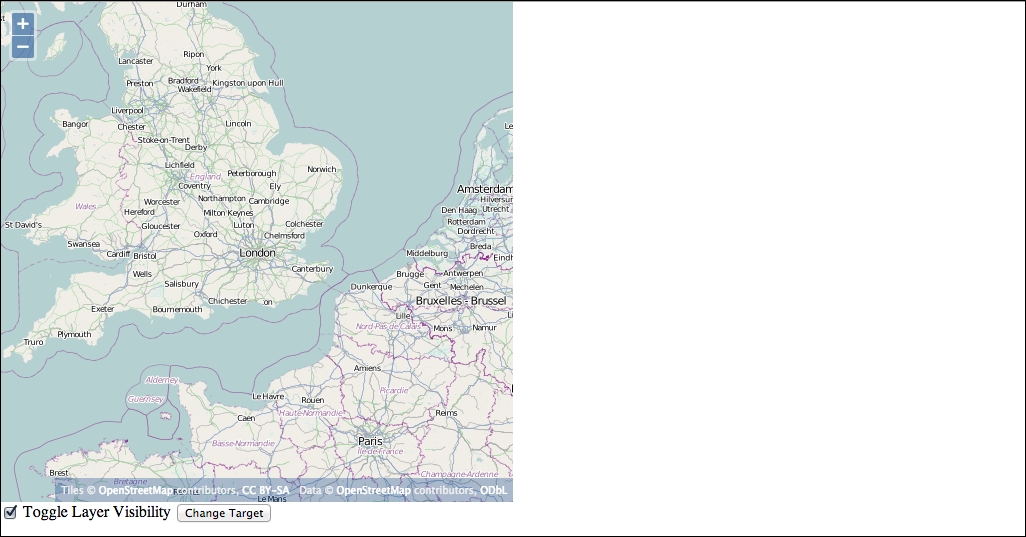

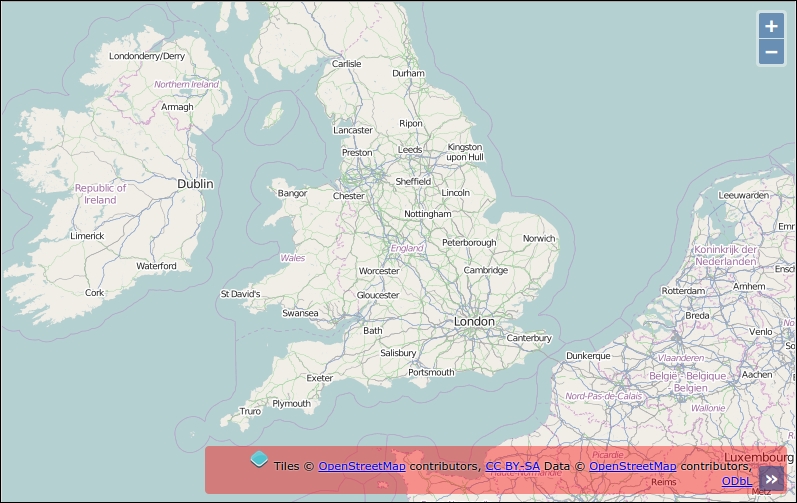

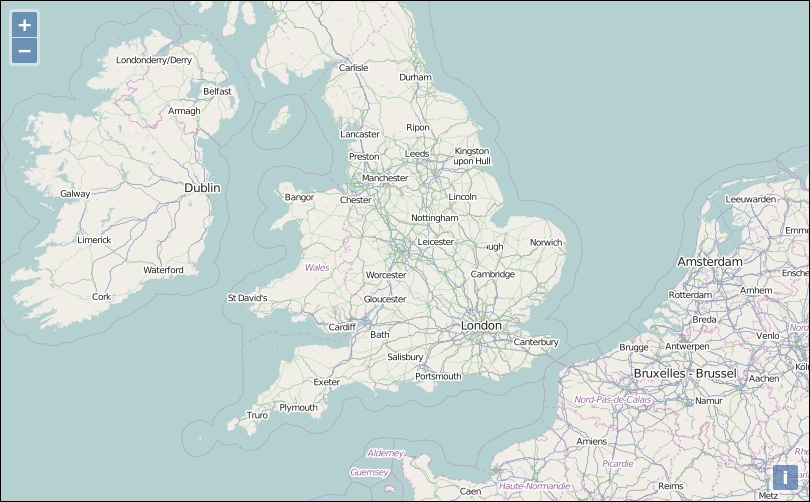

Let's dive into OpenLayers and make a map! After you finish this section, you should have a working map, which uses a publicly available OSM server backend from the OpenStreetMap.org project. Execute the following steps:

assets directory, create a folder css, and create a new file called samples.css. Add the following code:map {

height: 500px;

width: 100%;

background-color: #b5d0d0;

}hello_openstreetmap.html and save the file in the sandbox directory. If you are using Windows, we suggest using Notepad++ in particular because you need to be sure you're editing UTF-8 encoded files. On Linux, you can use Gedit or Geany and for Mac OSX, you can use Text Wrangler (free but not open source). Do not try to edit the file in a program such as Microsoft Word, as it will not save properly. The following code will also be used as the base template code for many future examples in this book, so we'll be using it often and coming back to it a lot:<!doctype html>

<head>

<title> Hello OpenStreetMap </title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="../assets/ol3/css/ol.css" type="text/css" />

<link rel="stylesheet" href="../assets/css/samples.css" type="text/css" />

</head>

<body>

<div id="map" class="map"></div>

<script src="../assets/ol3/js/ol.js">

</script>

<script>

var osmLayer = new ol.layer.Tile({

source: new ol.source.OSM()

});

var birmingham = ol.proj.transform([-1.81185, 52.44314], 'EPSG:4326', 'EPSG:3857');

var view = new ol.View({

center: birmingham,

zoom: 6

});

var map = new ol.Map({

target: 'map'

});

map.addLayer(osmLayer);

map.setView(view);

</script>

</body>

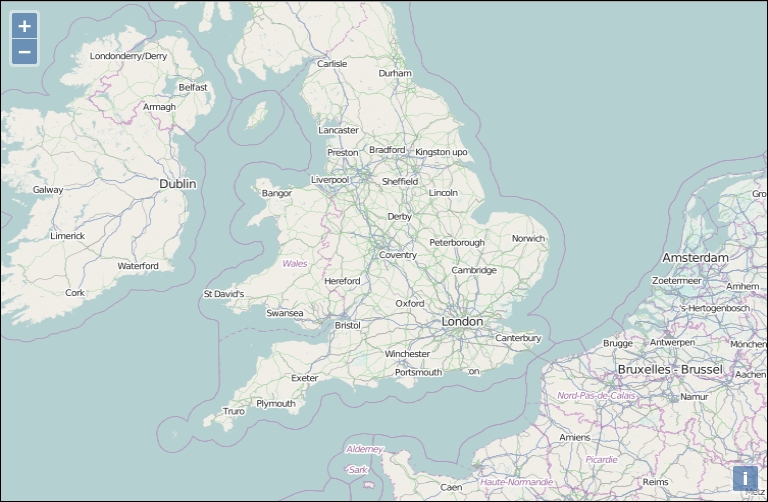

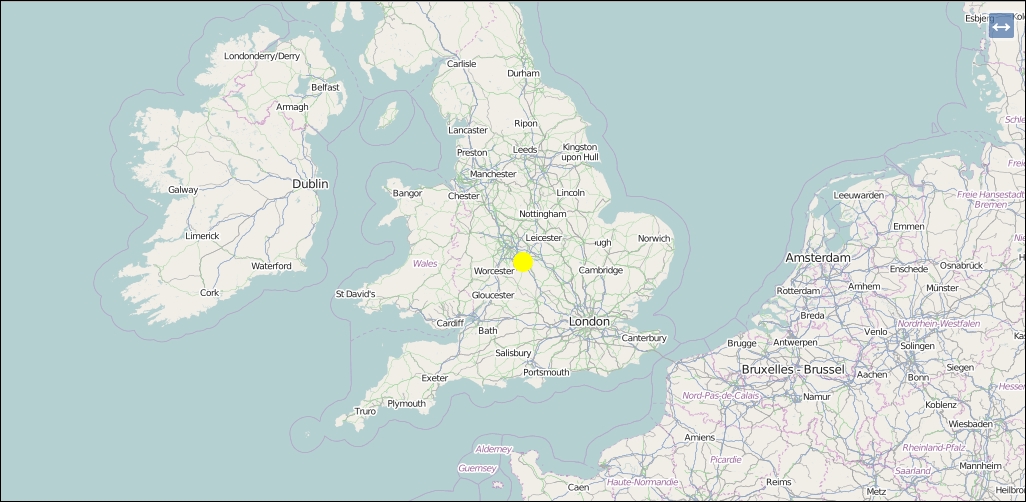

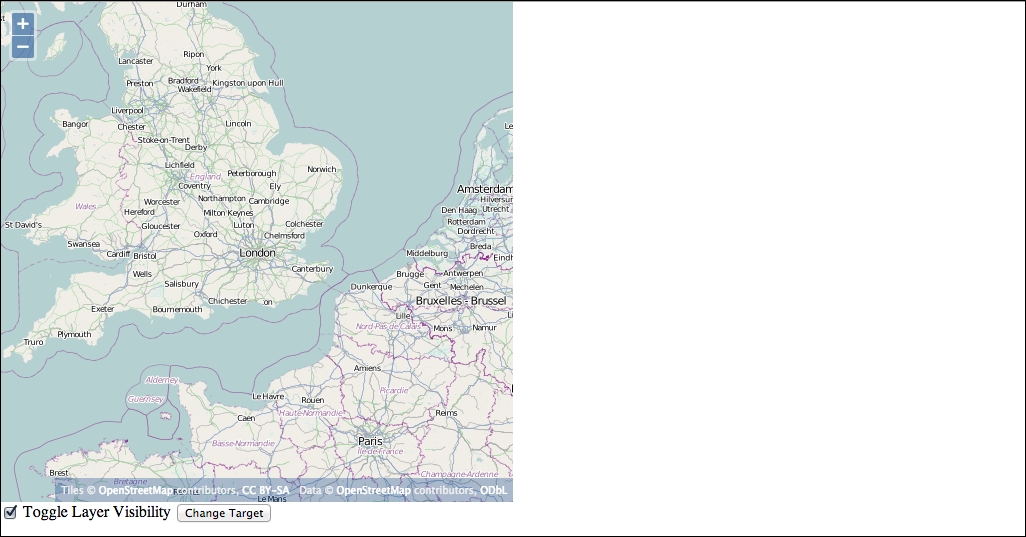

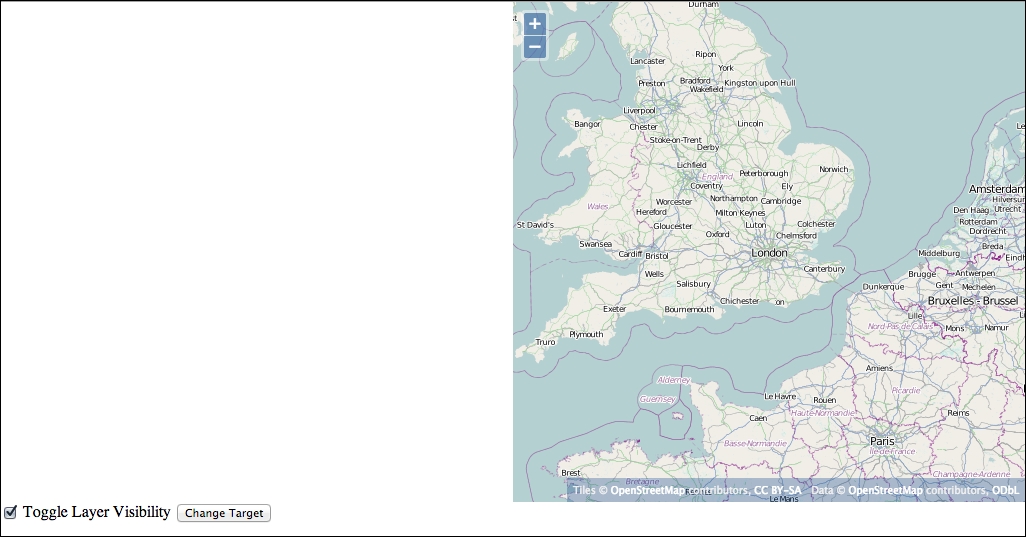

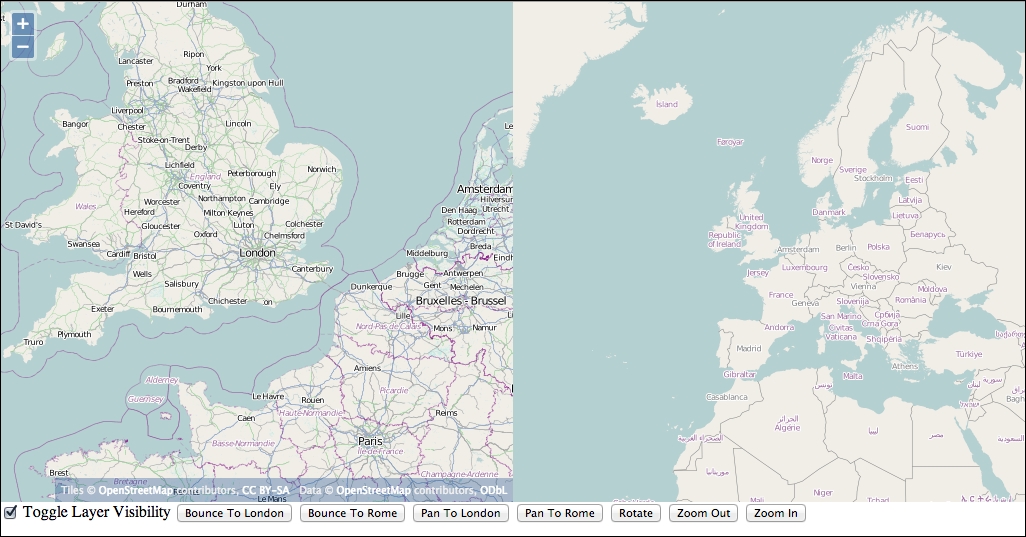

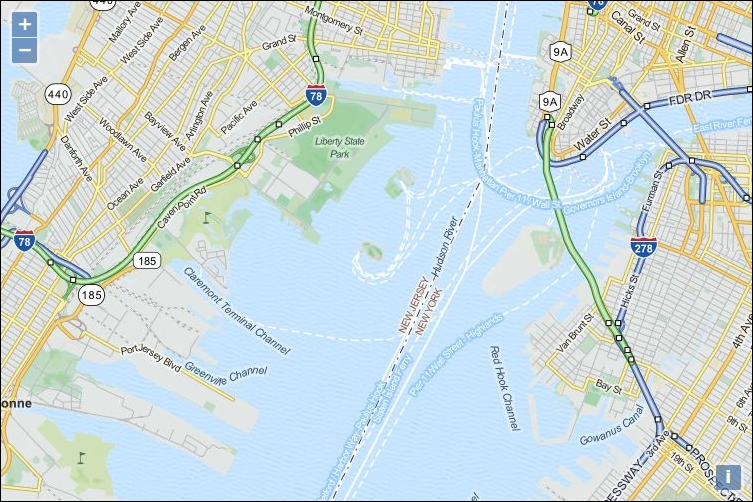

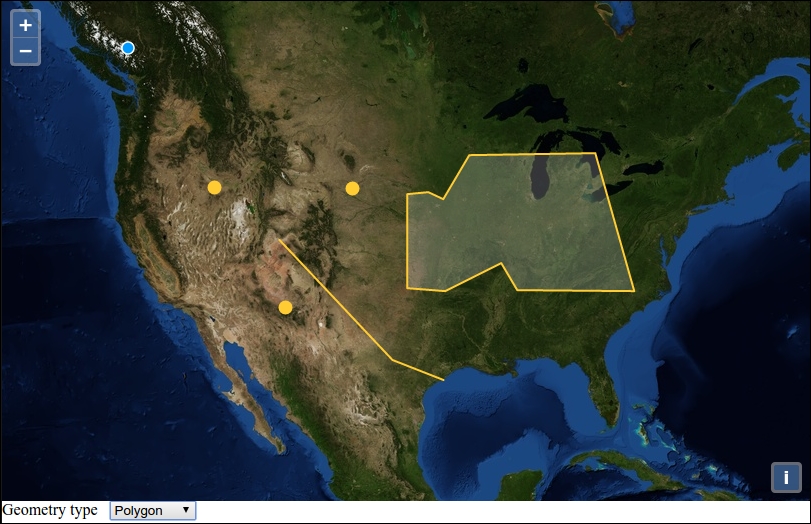

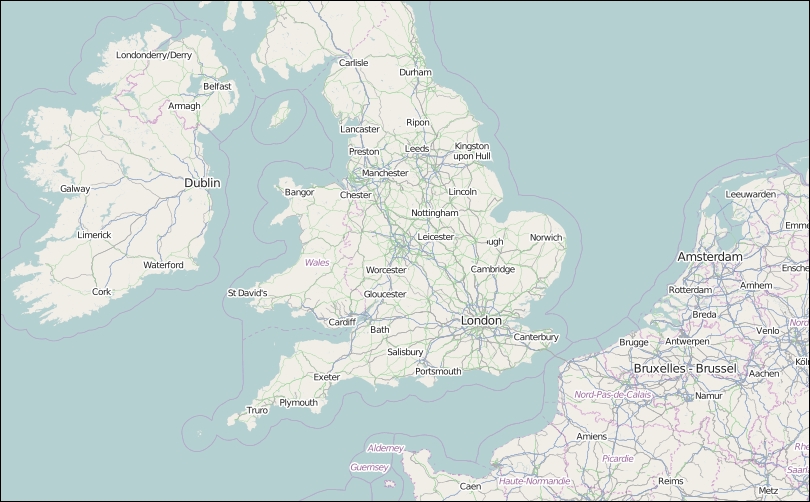

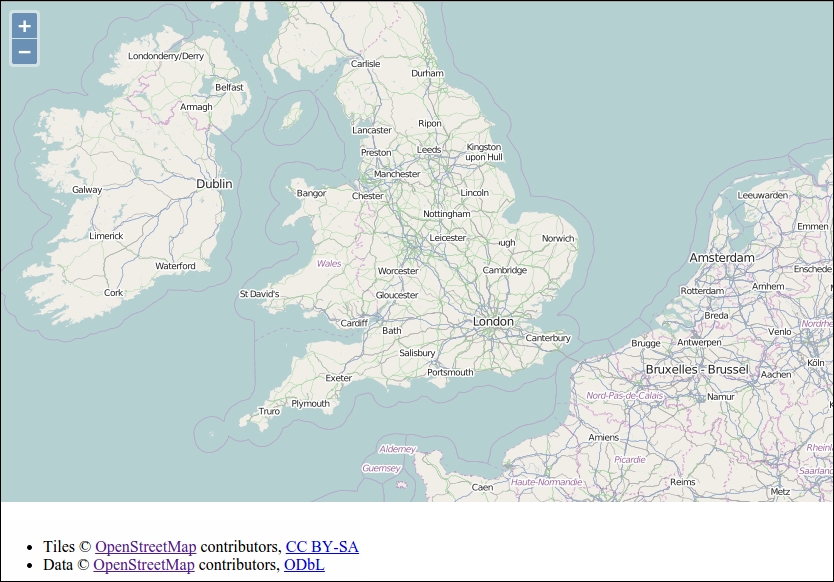

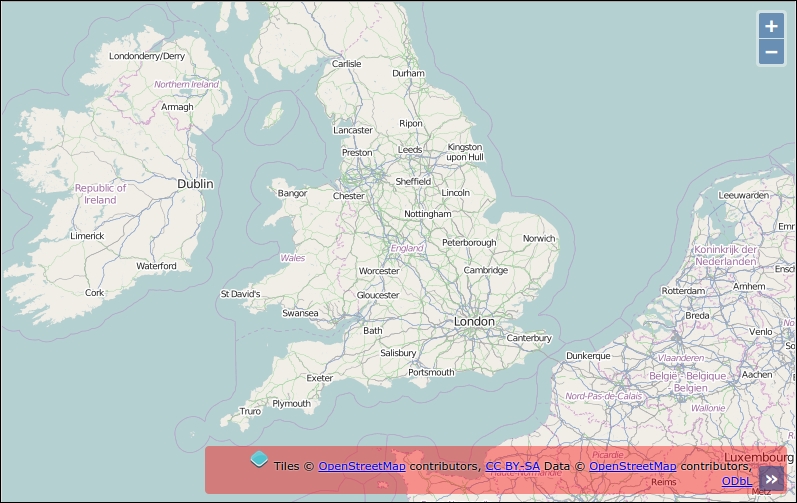

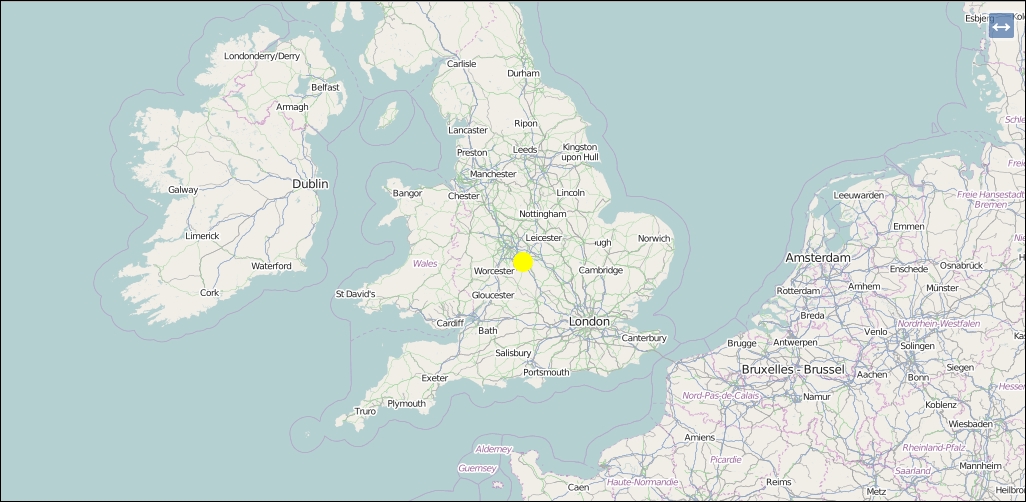

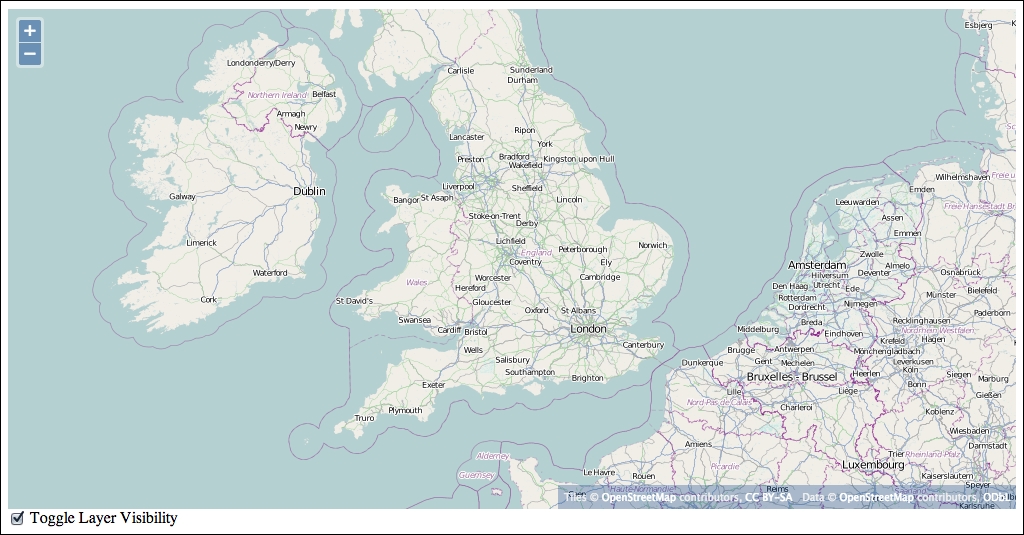

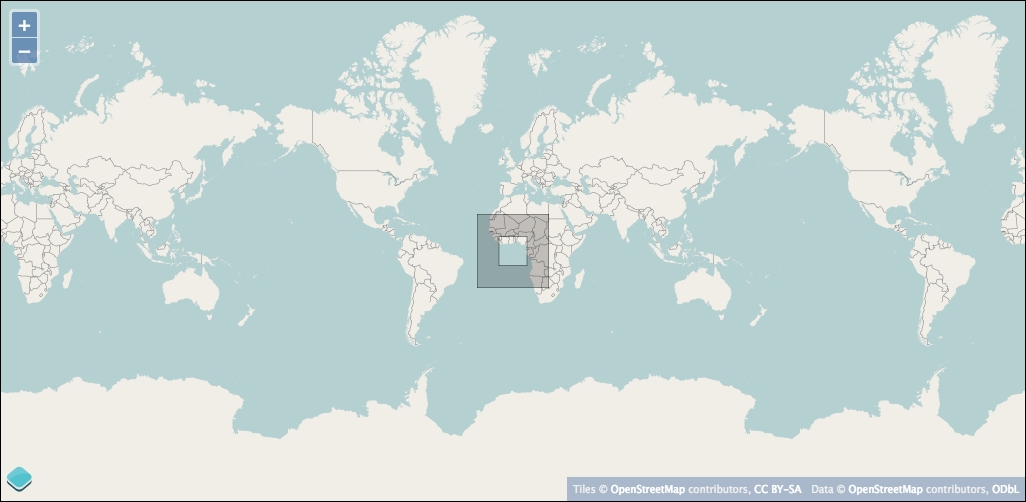

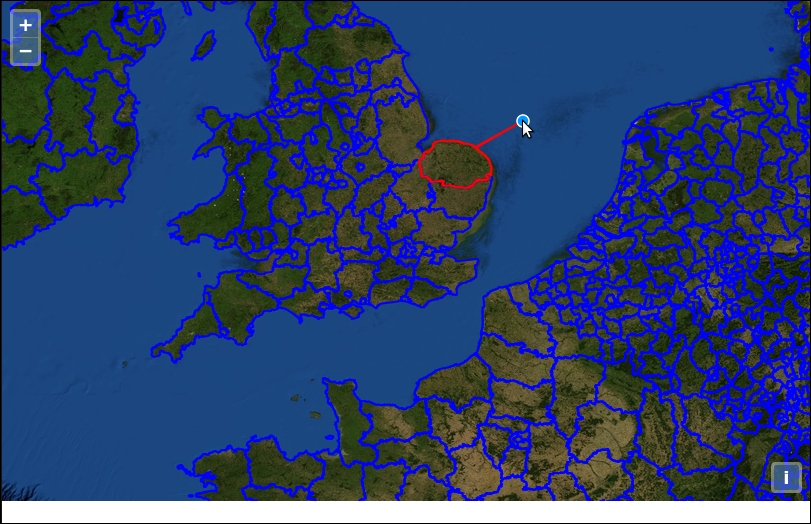

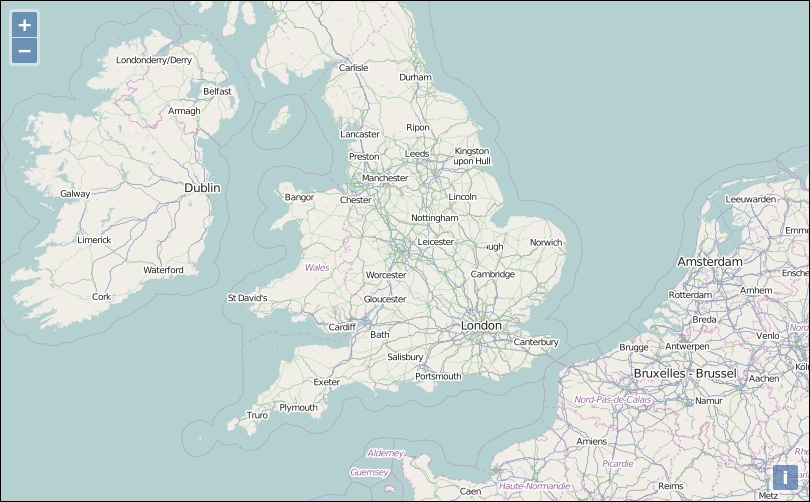

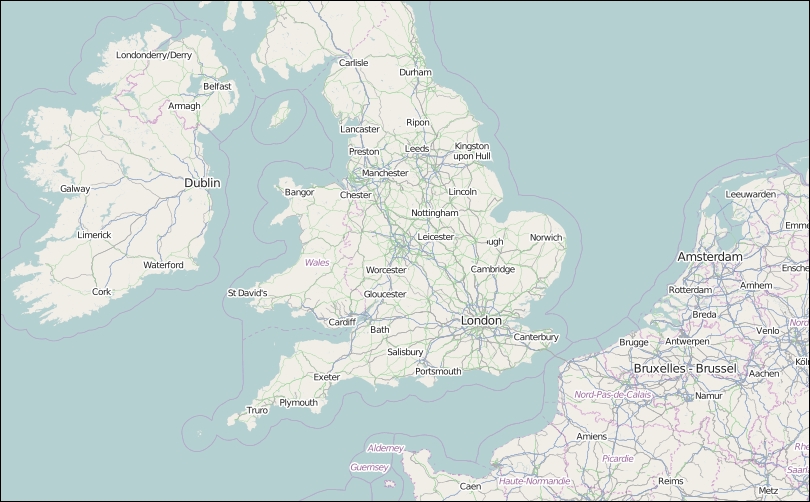

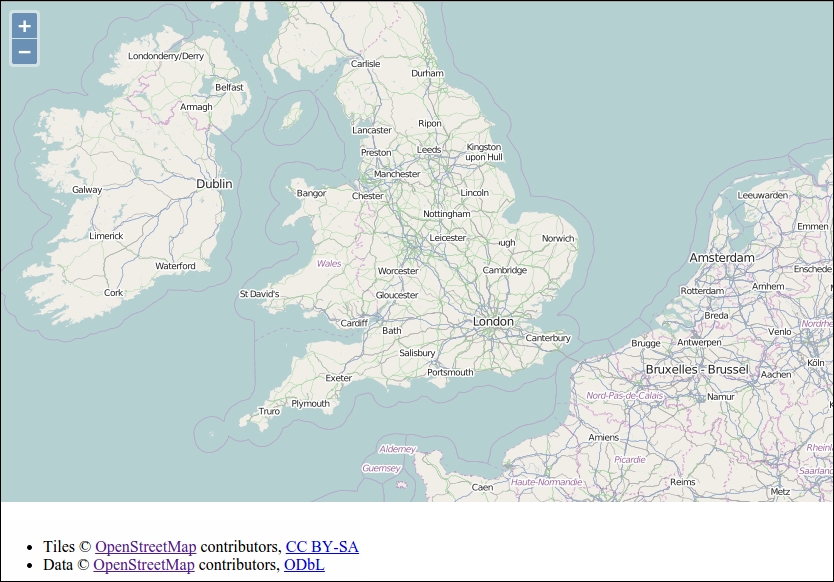

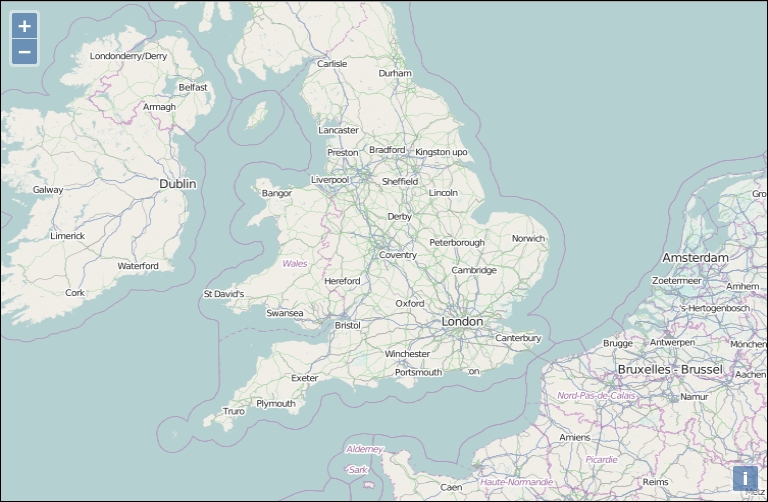

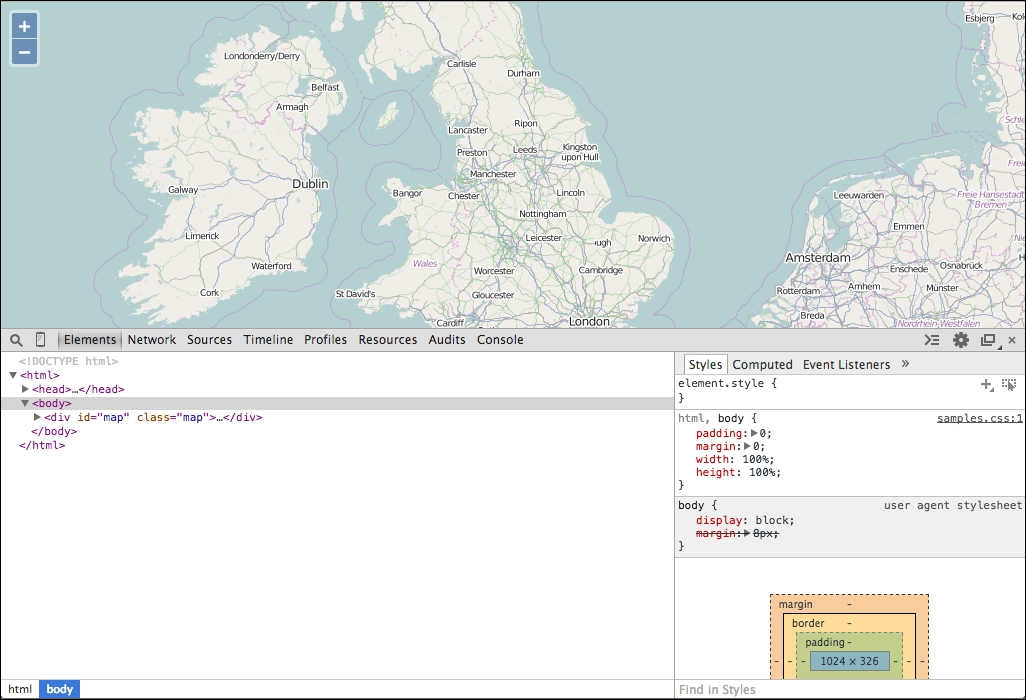

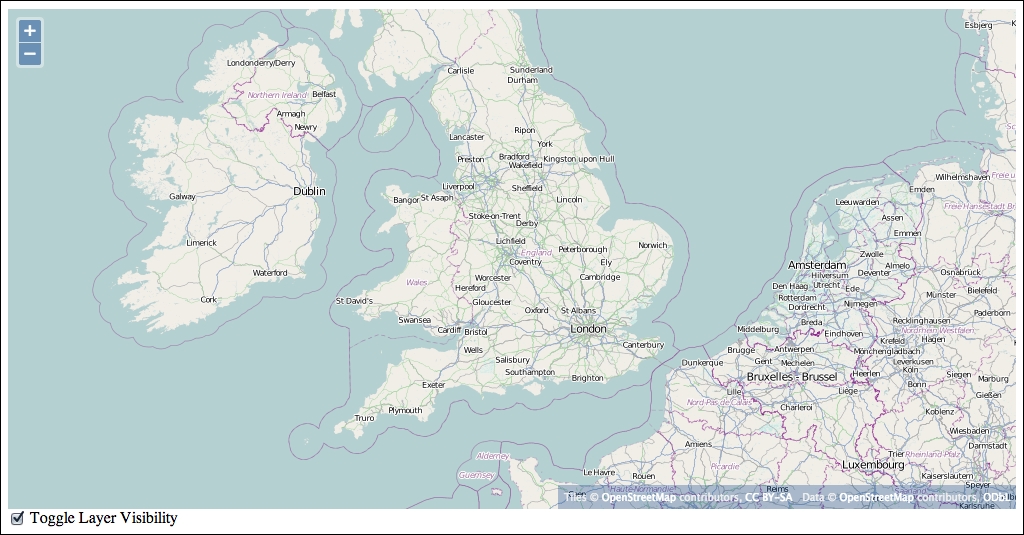

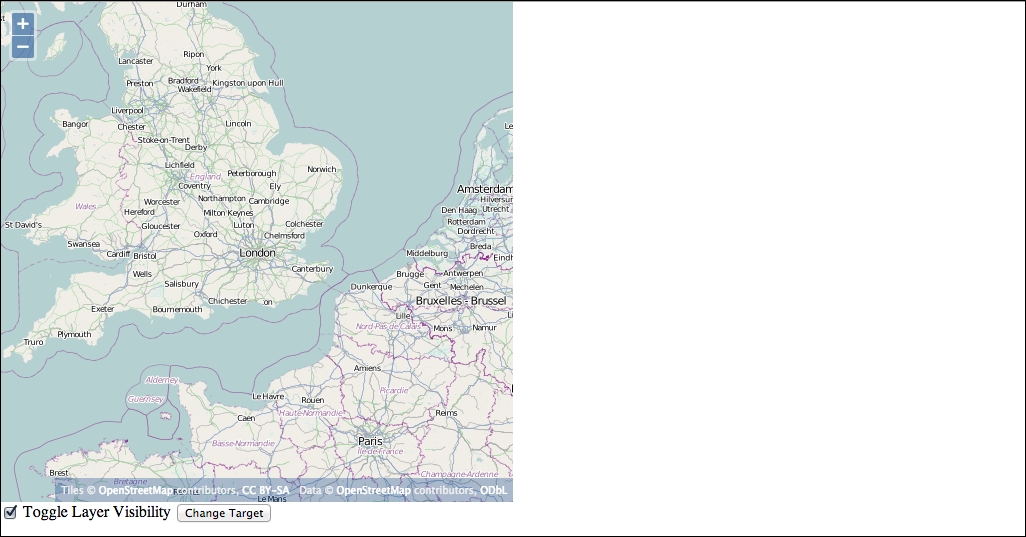

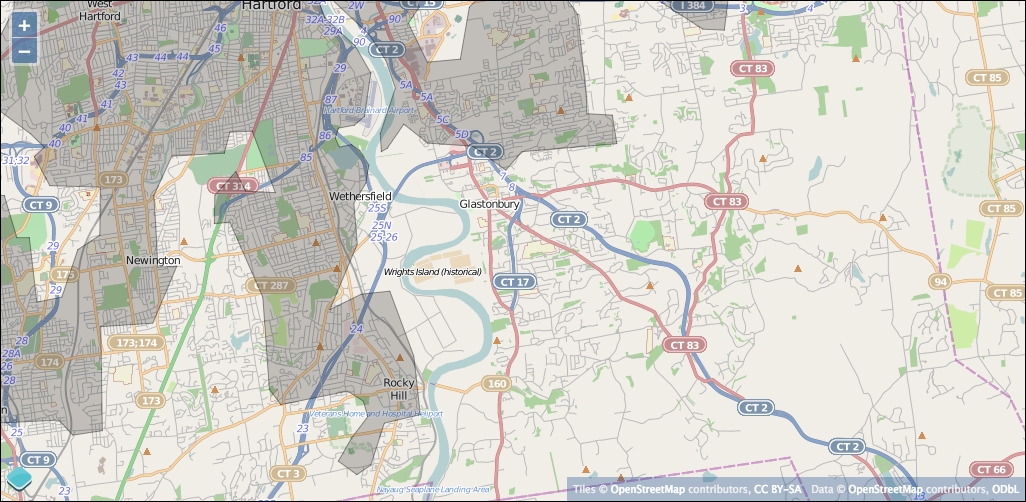

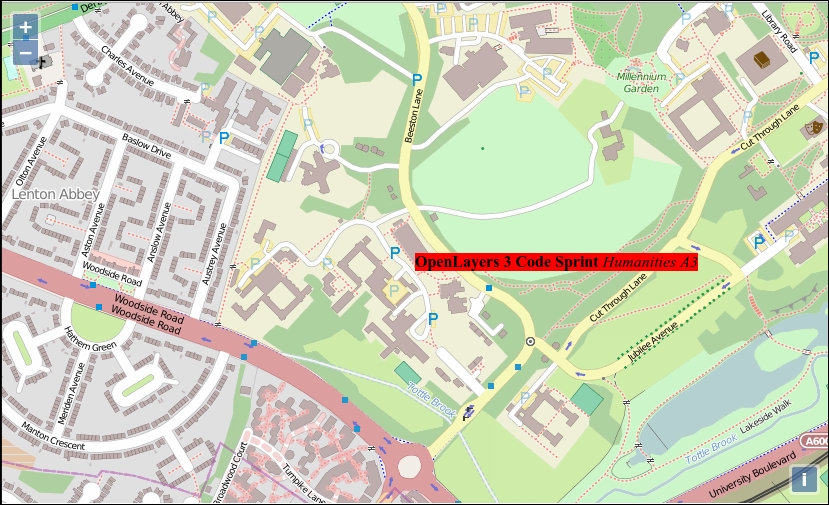

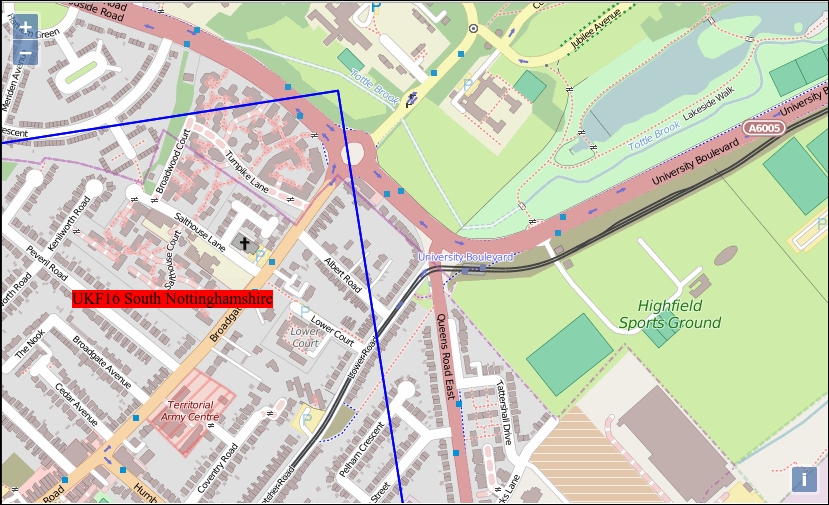

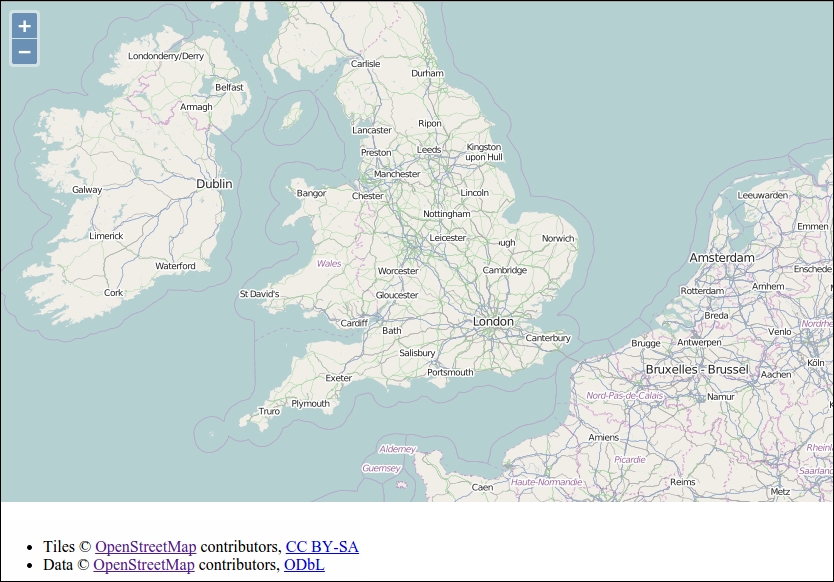

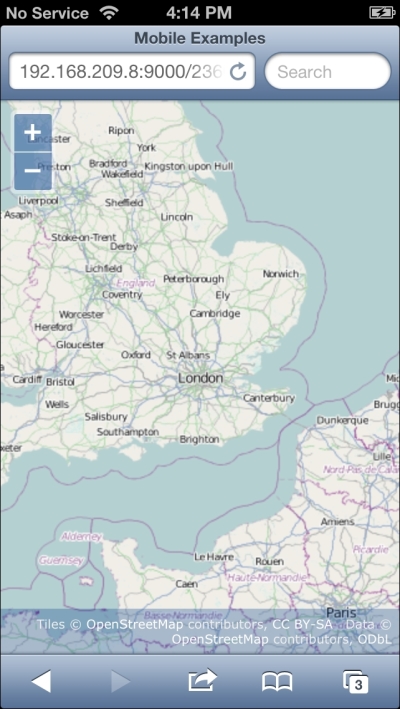

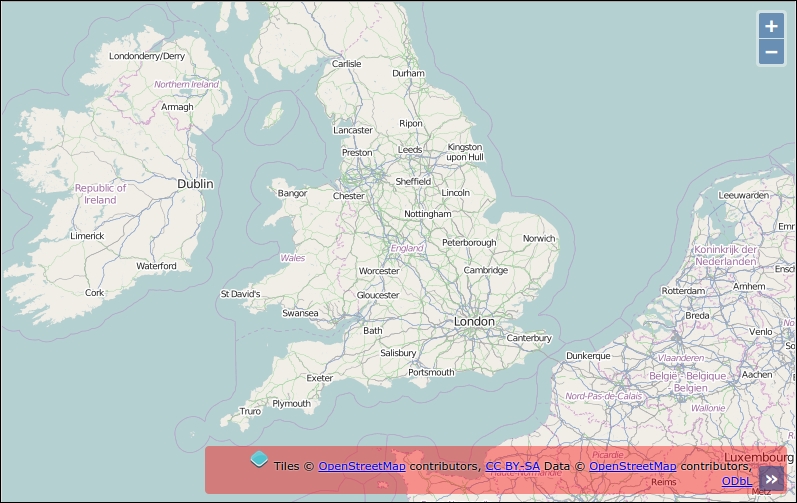

</html>hello_openstreetmap.html in your web browser. It can be hosted on a server or opened as a file. You should see something similar to the screenshot that follows:

We just created our first map using OpenLayers! If it did not work for you for some reason, try double-checking the code and making sure all the commas and parentheses are in place. You can also open the browser debugger and look for JavaScript errors within the console. If you don't know what a console is, don't worry, we will see it soon. You can also refer to the Preface where a link to code samples used in the book is given. By default, we're given a few controls if we don't specify any. We will use the file we created as a template for many examples throughout the book, so save a copy of it so you can easily refer to it later.

The control on the left side (the navigation buttons) is called the Zoom control, which is a ol.control.Zoom object. You can click the buttons to navigate around the map, drag the map with your mouse, use the scroll wheel to zoom in, or use your keyboard's arrow keys. ol.control.Attribution is added by default. It will be populated if a layer (such as OSM) has attribution info available. This control is on the bottom right corner and gives the credits for the data you're using such as license and data producer.

We'll cover controls in greater detail in Chapter 9, Taking Control of Controls.

Now, let's take a look at the code, line by line.

<html> and <head> tag, and the extraneous code you see specifies various settings that inform your browser that this is an HTML5 compliant page. For example, we include the DOCTYPE declaration in line 1 to specify that the page conforms to standards set by the WC3. We also specify a <title> tag, which contains the title that will be displayed on the page. We also add a css stylesheet content to display correctly the zoom and attribution controls, and set the future map size to a height of 500px and a width of 100% (the width will always be at the max width depending on the browser window).This is the structure that all our code examples will follow, so this basic code template will be implicitly assumed in all examples that follow throughout the book.

<body> <div id="map" class="map"></div>

To make an OpenLayers map, we need an HTML element where the map will be displayed in. Almost always, this element will be a div. You can give it whatever ID you would like, and the ID of this HTML element is passed into the call to create the map object. You can style the <div> tag however you would like—setting the width and height to be 100 percent, for instance, if you want a full page map. We choose a class for this, also called map.

<script src="../assets/ol3/js/ol.js" type="text/javascript"></script>

This includes the OpenLayers library. The location of the file is specified by the src='../assets/ol3/js/ol.js' attribute. Here, we're using a relative path. As the hello_openstreetmap.html page is within the sandbox at the same level as the assets, we need to go outside the sandbox directory and then set the path to ol.js file . The file could either be on your computer, or another computer. Browsers can load it on any computer thanks to the relative path.

We can also use an absolute path, which means we pass in a URL where the script is located at. openlayers.org hosts the script file as well; we could use the following line of code to link to the library file directly:

<script src='http://openlayers.org/en/v3.0.0/build/ol.js></script>

Notice how the src specifies an actual URL which is an absolute path http://openlayers.org/en/v3.0.0/css/ol.css at line 5. Either way works, however, throughout the book we'll assume that you are using a relative path and have the OpenLayers library on your own computer/server. If you use the hosted OpenLayers library, you cannot be sure that it will always be available, so using a local copy is recommended.

Be aware that when browsers load a page, they load it from top to bottom. To use any DOM (Document Object Model) elements (any HTML element on your page) in JavaScript, they first have to be loaded by the browser. So, you cannot reference HTML with JavaScript before the browser sees the element. It'd be similar to trying to access a variable that hasn't yet been created. Because of this behavior, don't forget to call your JavaScript content after the <div id="map" class="map"></div>.

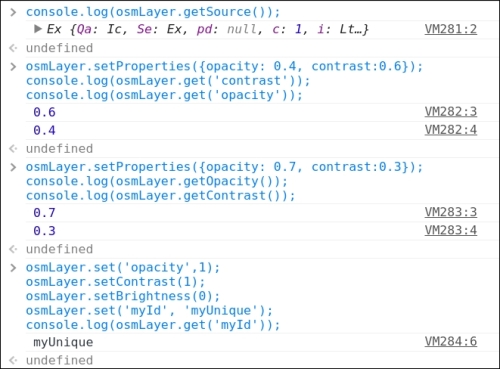

<script> block. We'll set up all our code inside it to create our map. Since the OpenLayers library has been included in line 13, we are able to use all the classes and functions the library contains. var osmLayer = new ol.layer.Tile({

source: new ol.source.OSM()

});In the previous three lines of code, we created a global variable called osmLayer. In JavaScript, any time we create a variable we need to place var in front of it to ensure that we don't run into scope issues (what functions can access which variables). When accessing a variable, you do not need to put var in front of it.

Since we are defining osmLayer as a variable at the global level (outside of any functions), we can access it anywhere in our code. We declare the osmLayer as an ol.layer.Tile object. It means we use an ol.layer.Tile class for creating the variable layerOsm.

The object created is also referred to as an instance of the ol.layer.Tile class. We'll talk about what this means later in the Appendix A, Object-oriented Programming – Introduction and Concepts.

Now, let's look at the right hand side of the equal sign (=): new keyword means that we are creating a new object from the class that follows it. ol.layer.Tile is the class name which we are creating an object from. Notice that something is inside the parenthesis: {source: new ol.source.OSM()}. This means we are passing one thing into the class (called an argument). Every class in OpenLayers expects different arguments to be passed into it, and some classes don't expect anything.

The ol.layer.Tile class expects one parameter following the API doc reference. Take a look at: http://openlayers.org/en/v3.0.0/apidoc/ol.layer.Tile.html. The {source: new ol.source.OSM()} is the layer options, consisting of key:value pairs (for example, {key:value} ). This is also called JavaScript Object Literal Notation, a way to create objects on the fly.

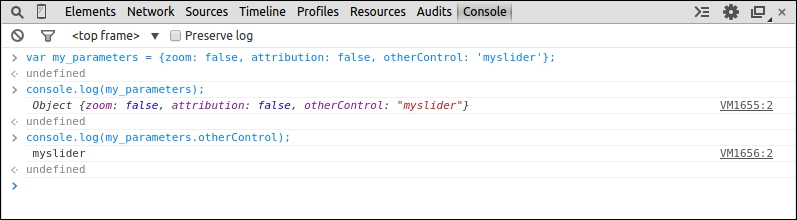

JavaScript object literal notation

In OpenLayers, we often pass in anonymous objects to classes . In JavaScript, anonymous objects are commas separated key:value pairs, and are set up in the format of {key1:value1, key2:value2}. They are, basically, objects that are created without deriving from a class. This format is also referred to as object literal notation.

When we say key1:value1, it's similar to saying key1 = value1, but we use a colon instead of an equals sign. We can also affect to a variable an object and reuse this variable instead of creating it on the line, for example:

var layer_parameters = {source: new ol.source.OSM()};

var osmLayer = new ol.layer.Tile(layer_parameters);So, the option source new ol.source.OSM() is the way to tell the characteristic of the tiles we want to retrieve such as the URL or the default attribution text, whereas ol.layer.Tile is the way to say how you ask the map image, not where it comes from.

The type of ol.source can be any from a multitude of different services, but we are using OSM here as a source. OSM (OpenStreetMap), is a crowdsourcing project focusing on creating open source map data. The main visible part of the project is the OSM world map we are using.

The arguments, like the source we can pass in for layers, are dependent on the layer class—we cover layers in detail in Chapter 3, Charting the Map Class. If you don't want to wait, you can also check out the documentation at http://openlayers.org/en/v3.0.0/apidoc/ to see what arguments different layers of classes expect.

var birmingham = ol.proj.transform([-1.81185 52.44314], 'EPSG:4326', 'EPSG:3857');

In this line of code, we take coordinates from a place, Birmingham in the UK, and we use a custom function that transforms [longitude, latitude] to the projected coordinate the map will expect in the view.

var view = new ol.View({ center: birmingham zoom: 6 });In the preceding four lines of code, we are defining a view from class ol.View. It's to use a view. Until now, we have defined what we will see, but with the view, we will define from where we are seeing it. Think of view as equivalent to a shot you might see in a cinema and where the cameraman chooses to see actors with more or less light, from far away or near, from below or above. Maps are usually 2D objects but because of new capabilities in the library, you can also have a tilted 2D view. We will not cover it because it requires advanced knowledge.

We have two options here in the JavaScript object: center and zoom.

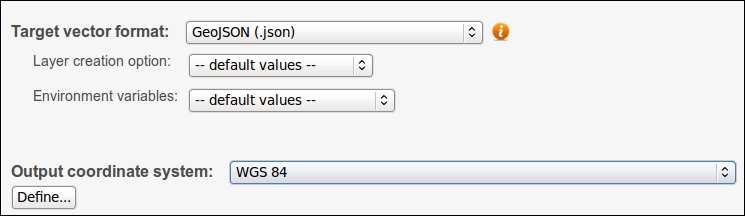

The first one sets the center of the map with coordinates. These are not using latitude and longitude coordinates but Spherical Mercator coordinates, a common web mapping standard projection. We will explain this topic in Chapter 7, Wrapping Our Heads Around Projections.

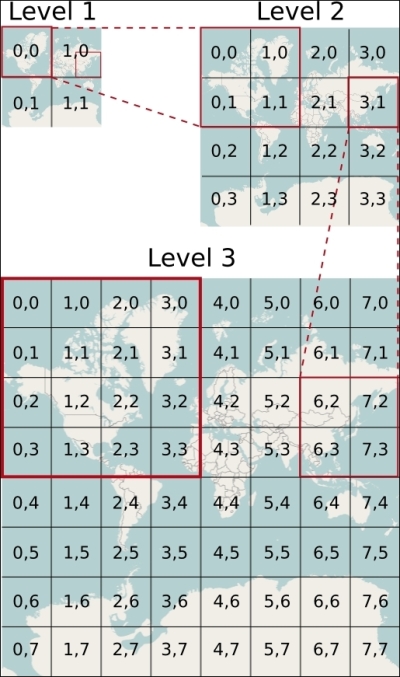

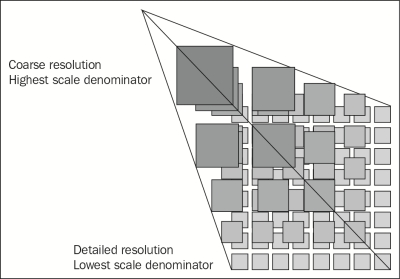

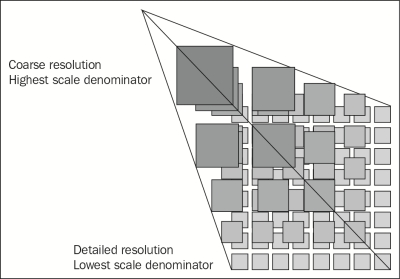

The zoom is a way to set the level of details you get on the map when you open the web page. Change this value to understand better. The value for using the OSM layer can be between 0 and 18. The more you increase the value, the more you zoom in. If you set the value to 20, you will see that the image is always of the level 18 but the library resizes the image itself and and the image quality will be reduced.

var map = new ol.Map({ target: 'map' });We previously created a layer in order to add it to a map but this map was not already created. We have done it using the ol.Map class. The map object is the crux of our OpenLayers application— we call its functions to tell the view bound to the map to zoom to areas, fire off events, keep track of layers, and so on.

The ol.Map class expects a JavaScript object parameter. Within this object, we use one object parameter: target. You can provide another parameter renderer to choose the way the image will be displayed in the browser. It can be, DOM, Canvas, or WebGL. Don't worry about these terms, we will explain what they cover. This is not a mandatory option but we'd prefer to tell you already to be aware of this. You will learn more about this in Chapter 2, Key Concepts in OpenLayers.

The other object parameter is target. Its purpose is to set where you will attach your map in the HTML. It refers to the id of an HTML element available in your web page.

Notice, we don't include everything on one line when creating our map object—this improves readability, making it easier to see what we pass in. The only difference is that we are also adding a new line after the comma separating arguments, which doesn't affect the code (but does make it easier to read).

map.addLayer(osmLayer);

Now that we have created both the map and layer, we can add the layer to the map. In OpenLayers, every map needs to have at least one layer. The layer points to the backend, or the server side map server, as we discussed earlier.

Notice, we are calling a function of the map object. There are actually a few ways to go about adding a layer to a map object. We can use the previous code (by calling map.addLayer), where we pass in an individual layer but we can also add the layers when instantiating the ol.Map with something such as the following:

var map = new ol.Map({ target: 'map',

layers: [osmLayer]

});In this second case, you have to create your layer before the map. Most official examples use the second syntax but for learning purposes, we thought it would be better to separate map instantiation from layers addition.

map.setView(view);

This line enables you to set the view to render the image and display it at the right place you defined previously in the ol.View instance, the view variable.

</script> </body> </html>

These lines close the JavaScript block and the remaining HTML blocks.

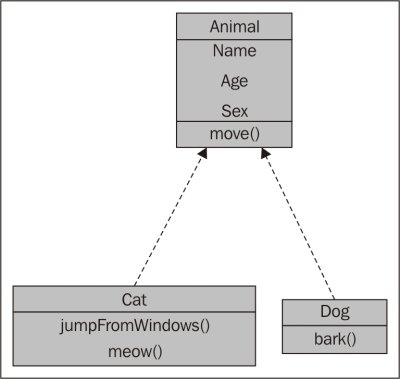

After reviewing this first example, if the concept of object-oriented programming is unfamiliar to you, we recommend that you take some time to explore this topic. While you don't necessarily need to know OOP concepts thoroughly to use this book, understanding keywords such as class, properties, abstract class, methods, instance, constructor, or inheritance should ring a bell in your mind. If not, we advise you to visit the Appendix A, Object-oriented Programming – Introduction and Concepts.

Now, let's introduce you to the main resources for getting the most important information about OpenLayers and its ecosystem.

Our coverage of the sample code was not meant to be extremely thorough; just enough to give you an idea of how it works. We'll be covering OOP concepts in more detail throughout the remaining chapters, so if anything is a bit unclear, don't worry too much.

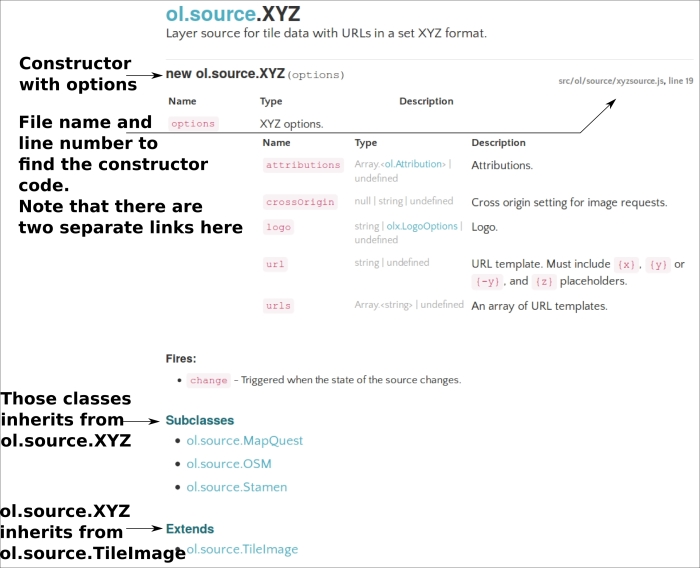

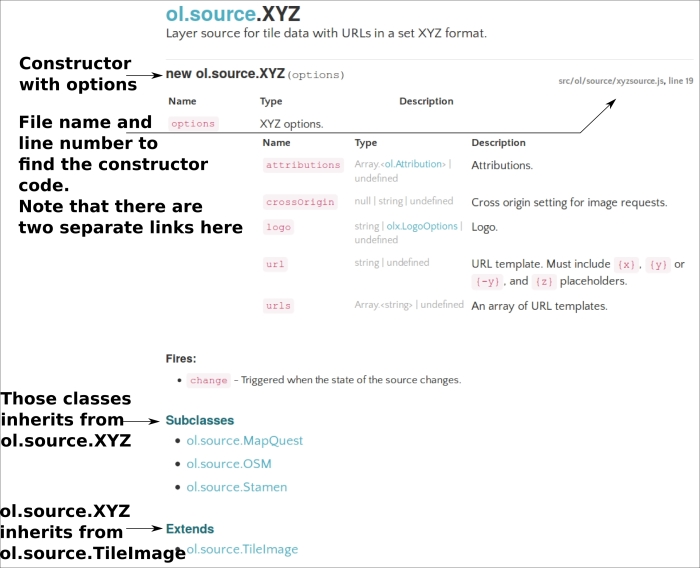

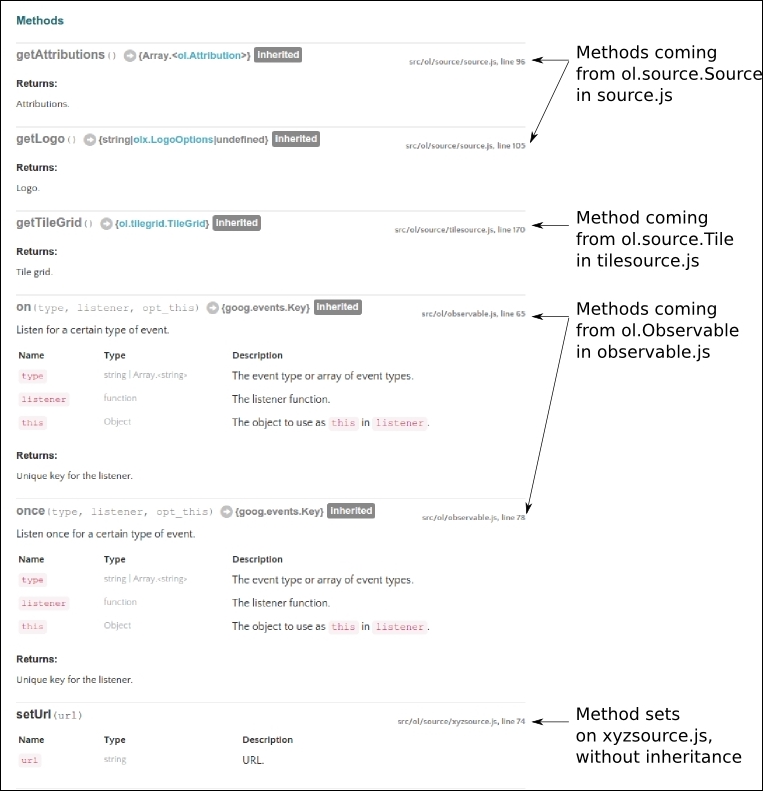

As OpenLayers is a library and provides functions for you, it is important to know what these functions are and what they do. There are many places to do this, but the best source is the API docs.

The API documentation is always up-to-date and contains an exhaustive description of all the classes in OpenLayers. It is usually the best and first place to go when you have a question. You can access the documentation at: http://openlayers.org/en/v3.0.0/apidoc/ for the 3.0.0 release. It contains a wealth of information. We will constantly refer to it throughout the book, so keep the link handy! Sometimes, however, the API docs may not seem clear enough, but there are plenty of other resources out there to help you. We'll cover a bit about how to find your way in API documentation in Chapter 2, Key Concepts in OpenLayers and in Appendix A, Object-oriented Programming – Introduction and Concepts.

The extension website for this book can be found at: http://openlayersbook.github.io/openlayersbook/. Current, up-to-date corrections and code fixes, along with more advanced tutorials and explanations, can be found there. You can also grab the code and more information about this book at Packt Publishing's website, located at https://www.packtpub.com/web-development/openlayers-3-beginner%E2%80%99s-guide.

The OpenLayers mailing list is an invaluable resource that lets you not only post questions, but also browse questions others have asked (and answered). There were two main OpenLayers news groups—Users and Dev for the OpenLayers 2 Version. There is a list only for OpenLayers 3 development discussions located at https://groups.google.com/forum/#!forum/ol3-dev. You may find some users' questions in the archives as it was before for both development and users questions.

Now, user questions should be only posted on http://stackoverflow.com and tagged with openlayers. OpenLayers 3 library developers will answer directly here.

When posting a question, please be as thorough as possible, stating your problem, what you have done, and the relevant source code (for example, "I have a problem with using a WMS layer. I have tried this and that, and here is what my source code looks like..."). A good guideline for asking questions in a way that will best elicit a response can be found at http://www.catb.org/~esr/faqs/smart-questions.html.

Books are great, but they're basically just a one way form of communication. If you have any questions that the book does not answer, your favorite search engine is the best place to go to. The Questions and Answers website http://gis.stackexchange.com, the young brother of StackOverflow, dedicated to GIS (Geographical Information System) can also be quite useful. But, at the end, don't forget that mailing lists and IRC are other great resources.

Sometimes, you will hit an error without understanding why you encounter it, for example related to a mobile browser's unexpected behavior. Before asking to check mailing lists or IRC, we encourage you to make a small search in the list of issues located at Github https://github.com/openlayers/ol3/issues. You can search issues by milestone, status (opened, closed, etc), or keywords.

IRC (Internet Relay Chat) is another great place to go to if you have questions about OpenLayers. IRC is used for group communication; a big chat room, essentially. If you have exhausted Google, issues' trackers, and the mailing list, IRC provides you in real time with other people interested in OpenLayers.

Generally, the people who hang out in the OpenLayers chat room are very friendly, but please try to find an answer before asking in IRC. The server is irc.freenode.net and the chat room is #openlayers. You can download an IRC client online; a good Windows one is mIRC (http://mirc.com). More information about how to use IRC can be found at http://www.mirc.com/install.html. For beginners, we recommend using Chatzilla, a Firefox Mozilla add—on http://chatzilla.hacksrus.com or CIRC, a Google Chrome add—on http://flackr.github.io/circ/.

When you've installed it, just type irc://irc.freenode.net/openlayers (for Chatzilla only) in your browser address bar, press enter, wait and you're ready to speak on OpenLayers IRC channel.

The source code repository location is hosted at GitHub. You can access the entire code repository at http://github.com/openlayers/ol3.

Feel free to download a copy and play around with it yourself. When you become an advanced user, you can submit evolutions to the official source code base and become a contributor to the library. Without going so far, it cannot hurt to download a copy of the code base and look around it yourself to figure out how it's really working!

Nowadays, some people prefer to aggregate content using RSS feeds or social networks.

Let's review how you can access alternatively to all the previous resources and more.

For the OpenLayers 3 Developers mailing list, you can use atom or RSS feed, available at https://groups.google.com/forum/#!aboutgroup/ol3-dev

When you want to get news about OpenLayers 3 development, you have to rely on Github website capabilities.

You can see:

In this chapter, we were introduced to OpenLayers and learnt a bit about it.

We saw what web map applications are and how they work. After that, we created our first map with OpenLayers, then analyzed how the code works. Then, we covered a fundamental concept, object-oriented programming, which we'll need to know about while really working with OpenLayers. Lastly, resources for help and information outside this book were provided.

Now that we have a basic handle on OpenLayers, we'll jump straight into Chapter 2, Key Concepts in OpenLayers. We will discover relationships between library core parts. Using examples, we will also review Events and Observe behaviors. It would be impossible to get an interactive map without them. Then, to finish, we will focus on basic debugging techniques. To learn more about JavaScript debugging, you can also refer to Appendix C, Squashing Bugs with Web Debuggers.

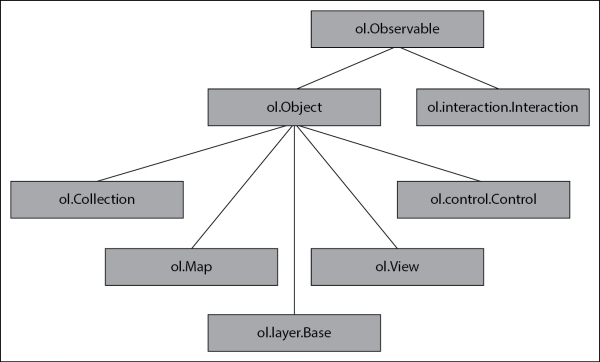

Now that we've seen the basics and made our first map with OpenLayers, let's take a step back and look at the big picture. OpenLayers is a software library based on an Object-oriented design principles, which means that it contains classes to encapsulate behavior, formal relationships between those classes, and standardized mechanisms for communication between objects. While OpenLayers contains many classes, there are just a few that form the foundation of the OpenLayers architecture. In this chapter, we will introduce these core components of the library and also two key concepts— events and observable properties—that are the basis for standardized communication between objects. Along the way, we'll use concrete examples and introduce some basic debugging techniques you can use to solve problems and explore the relationships between objects in a running application.

In this chapter, we will:

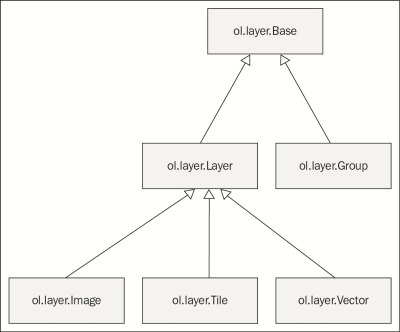

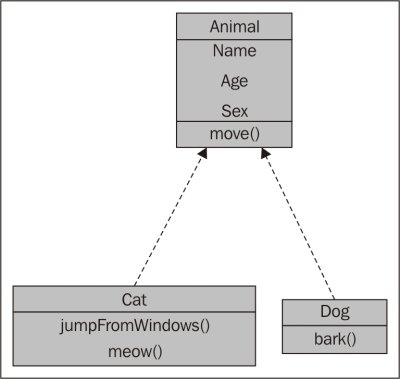

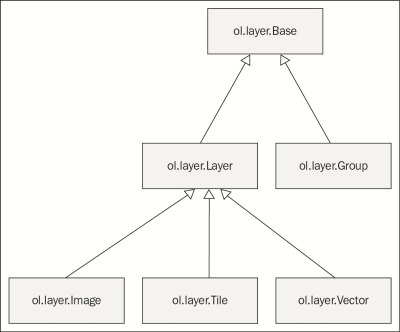

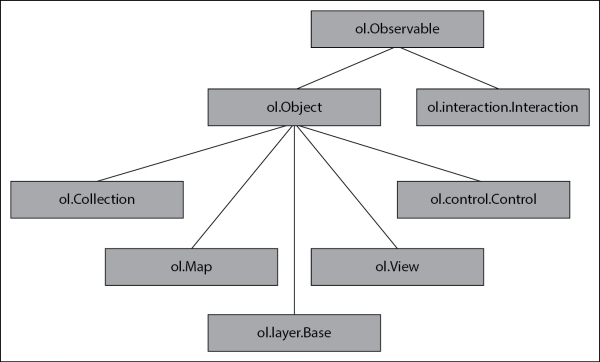

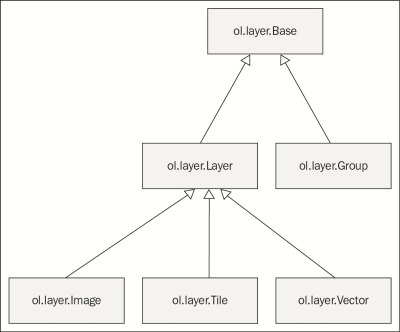

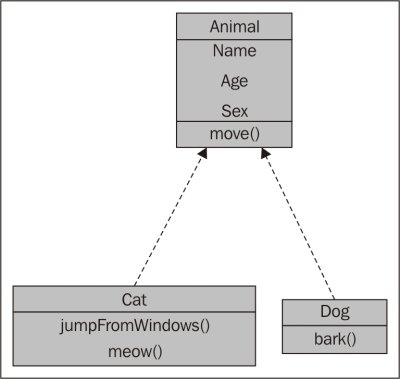

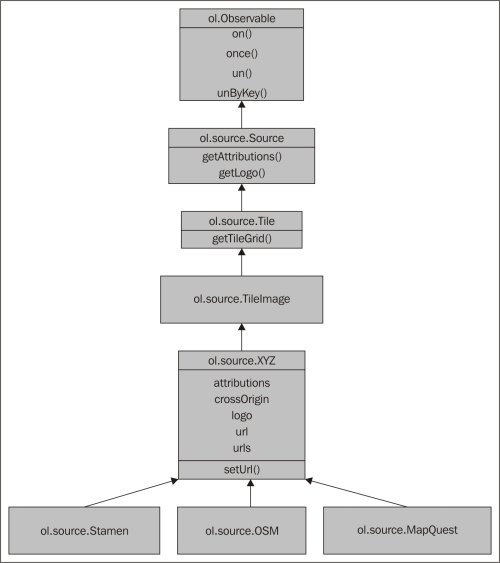

The OpenLayers library provides web developers with components useful to build web mapping applications. Following the principles of an Object-oriented design, these components are called classes. The relationship between all the classes in the OpenLayers library is part of the deliberate design, or architecture, of the library. There are two types of relationships that we, as developers using the library, need to know about: relationships between classes and inheritance between classes. We briefly talked about object-oriented programming in Chapter 1, Getting Started with OpenLayers and a more detailed discussion is included in Appendix A, Object-oriented Programming – Introduction and Concepts but for the purpose of this chapter, let's summarize the two types of relationships we are interested in:

We'll start our discussion of the key components of OpenLayers by focusing on the first of these—the relationship between classes. OpenLayers includes a lot of classes for our use, and we'll cover a lot of these in later chapters, but for now, we'll start by looking at the Map class—ol.Map.

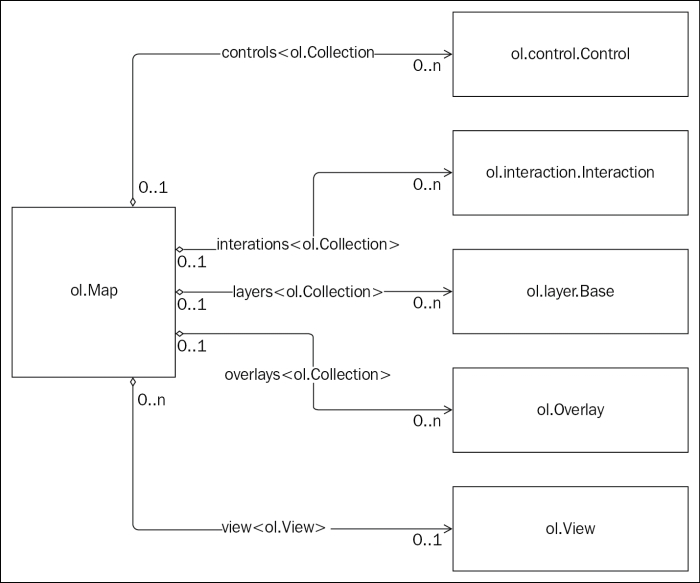

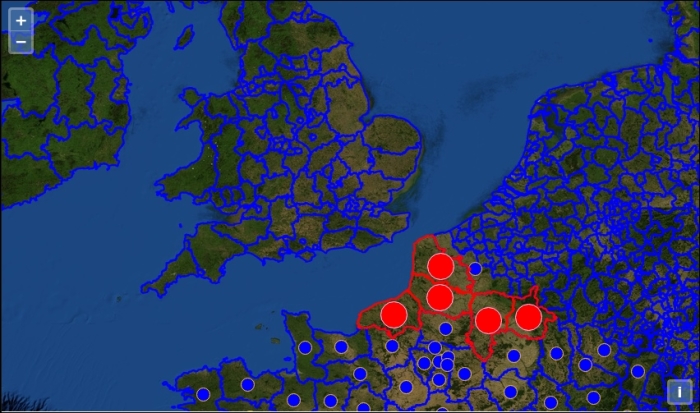

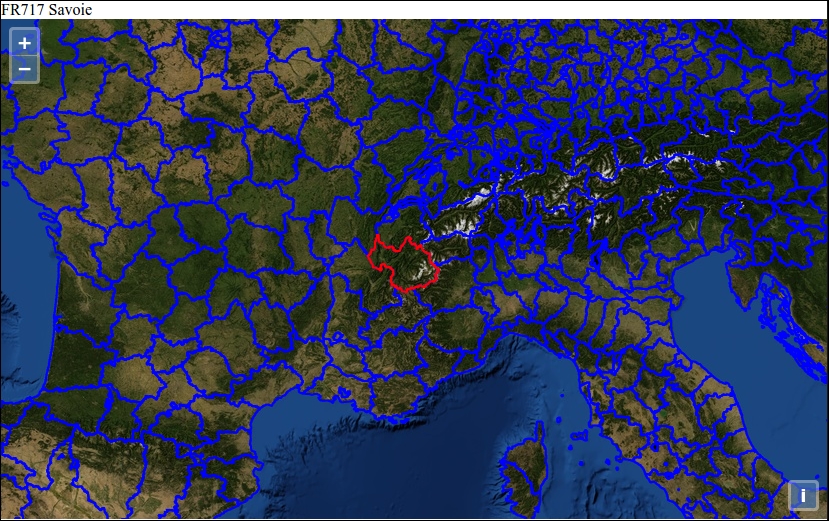

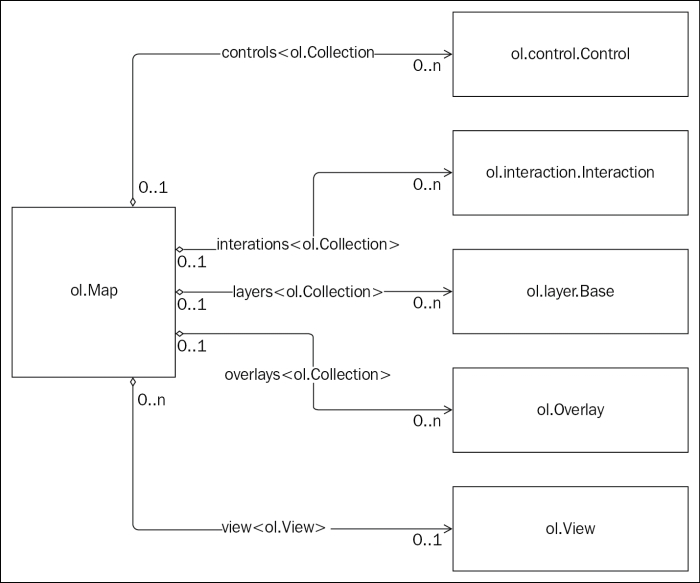

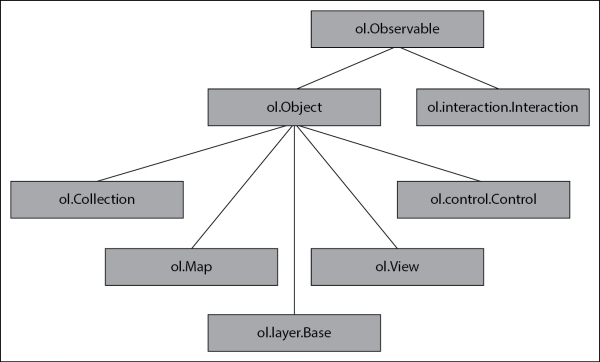

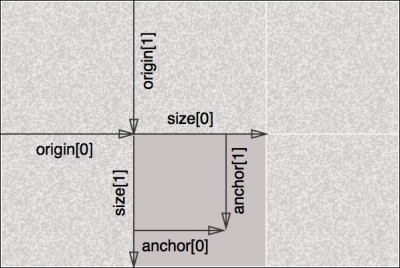

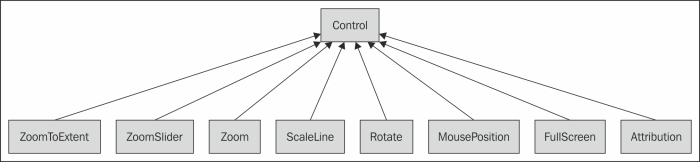

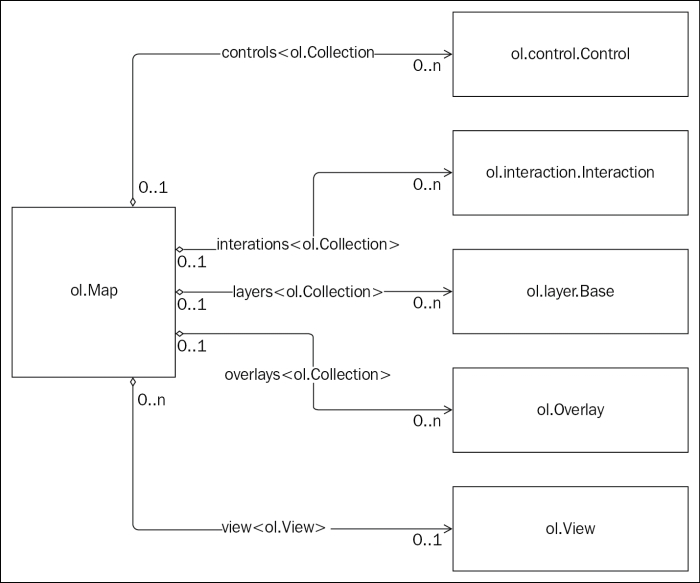

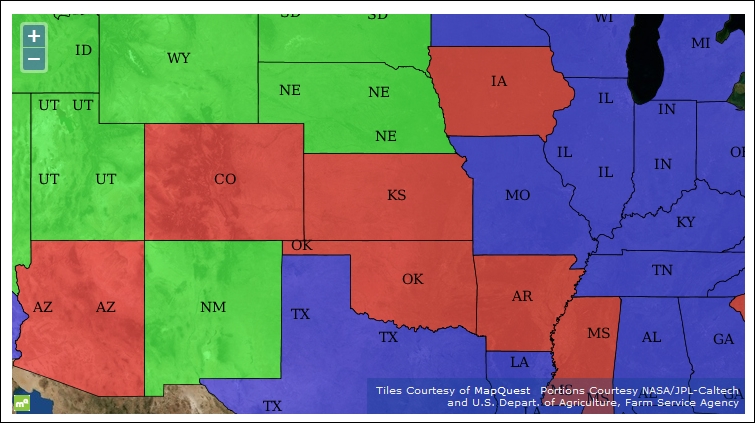

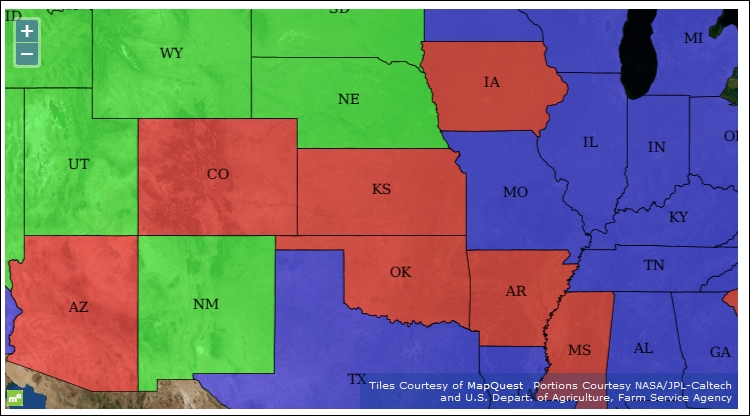

Instances of the map class are at the center of every OpenLayers application. These objects are instances of the ol.Map class and they use instances of other classes to do their job, which is to put an interactive map onto a web page. Almost every other class in the OpenLayers is related to the Map class in some direct or indirect relationship. The following diagram illustrates the direct relationships that we are most interested in:

The preceding diagram shows the most important relationships between the Map class and other classes it uses to do its job. It tells us several important things:

view to refer to it. A view may be associated with multiple maps, however.Collection class and a layer may be associated with 0 or one Map class. The Map class has a member variable named layers that it uses to refer to this collection.Collection class and an overlay may be associated with 0 or one Map class. The Map class has a member variable named overlays that it uses to refer to this collection.ol.Collection (more on collections at the end of this chapter) and controls may be associated with 0 or one Map class. The Map class has a member variable named controls that it uses to refer to this collection.Collection class and an interaction may be associated with 0 or one Map class. The Map class has a member variable named interactions that it uses to refer to this collection.Although these are not the only relationships between the Map class and other classes, these are the ones we'll be working with the most. We've already seen some of these classes in action in the examples from the previous chapter. We'll do another example in a moment, but first let's introduce each of these new classes.

View class (ol.View) manages information about the current position of the Map class.If you are familiar with the programming concept of MVC (Model-View-Controller), be aware that the view class is not a View in the MVC sense. It does not provide the presentation layer for the map, rather it acts more like a controller (although there is not an exact parallel because OpenLayers was not designed with MVC in mind.)

Layer class (ol.layer.Base) is the base class for classes that provide data to the map to be rendered.Overlay class (ol.Overlay) is an interactive visual element like a control, but it is tied to a specific geographic position.Control class (ol.control.Control) is the base class for a group of classes that collectively provide the ability to a user to interact with the map. Controls have a visible user interface element (such as a button or a form input element) with which the user interacts.Interaction class (ol.interaction.Interaction) is the base class for a group of classes that also allow the user to interact with the map, but differ from controls in which they have no visible user interface element. For example, the DragPan interaction allows the user to click on and drag the map to pan around.Let's create a new OpenLayers application and identify the components as we go:

components.html in the sandbox directory and put in the standard HTML structure for our applications as follows:<!doctype html>

<html>

<head>

<title>OpenLayers Components</title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="../assets/ol3/css/ol.css" type="text/css" />

<link rel="stylesheet" href="../assets/css/samples.css" type="text/css" />

</head>

<body>

<div id="map" class="map"></div>

<script src="../assets/ol3/js/ol.js"></script>

<script>

</script>

</body>

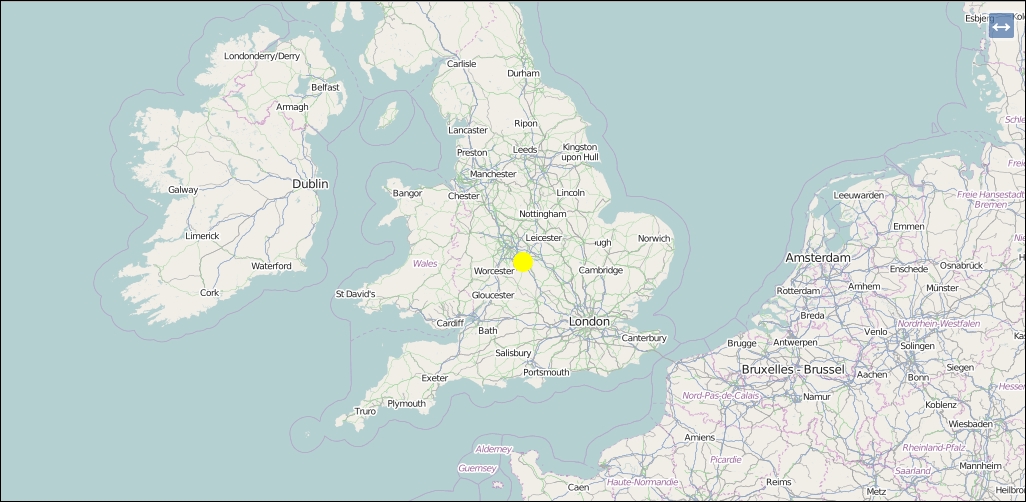

</html>layers collection:var layer = new ol.layer.Tile({

source: new ol.source.OSM()

});DragRotateAndZoom:var interaction = new ol.interaction.DragRotateAndZoom();

FullScreen:var control = new ol.control.FullScreen();

<div> tag containing our map:<div id="overlay" style="background-color: yellow; width: 20px; height: 20px; border-radius: 10px;">

var center = ol.proj.transform([-1.812, 52.443], 'EPSG:4326', 'EPSG:3857');

var overlay = new ol.Overlay({

position: center,

element: document.getElementById('overlay')

});var view = new ol.View({

center: center,

zoom: 6

});var map = new ol.Map({

target: 'map',

layers: [layer],

interactions: [interaction],

controls: [control],

overlays: [overlay],

view: view

});

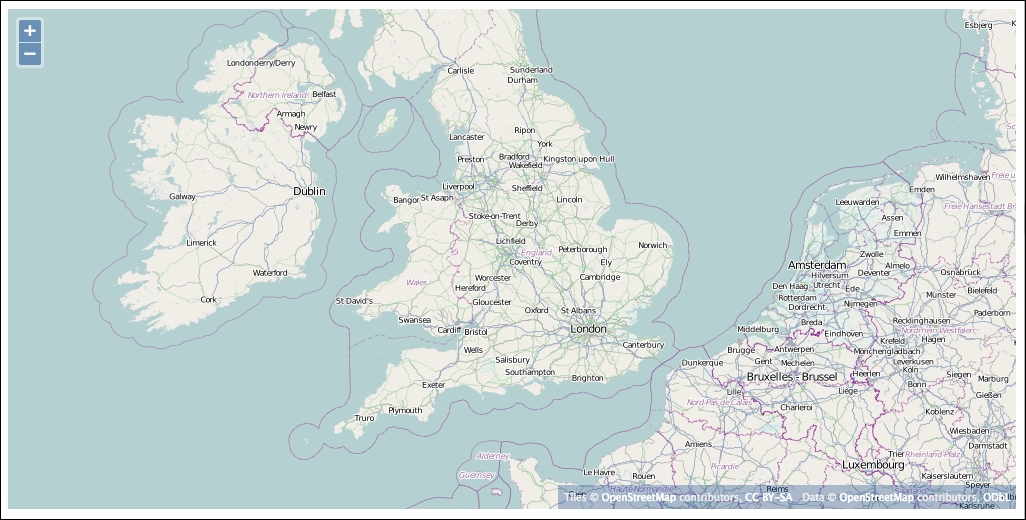

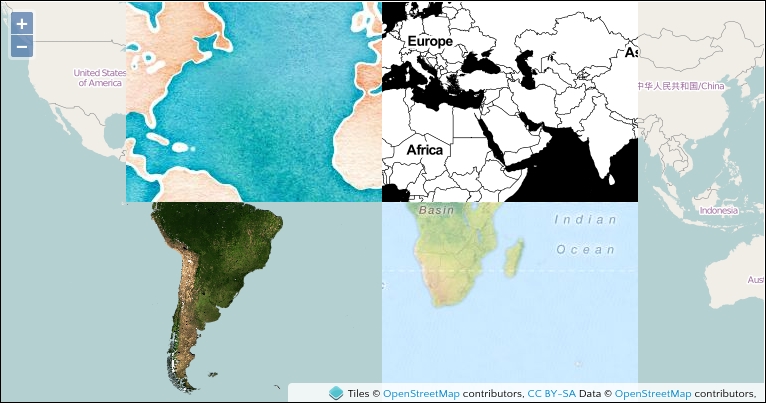

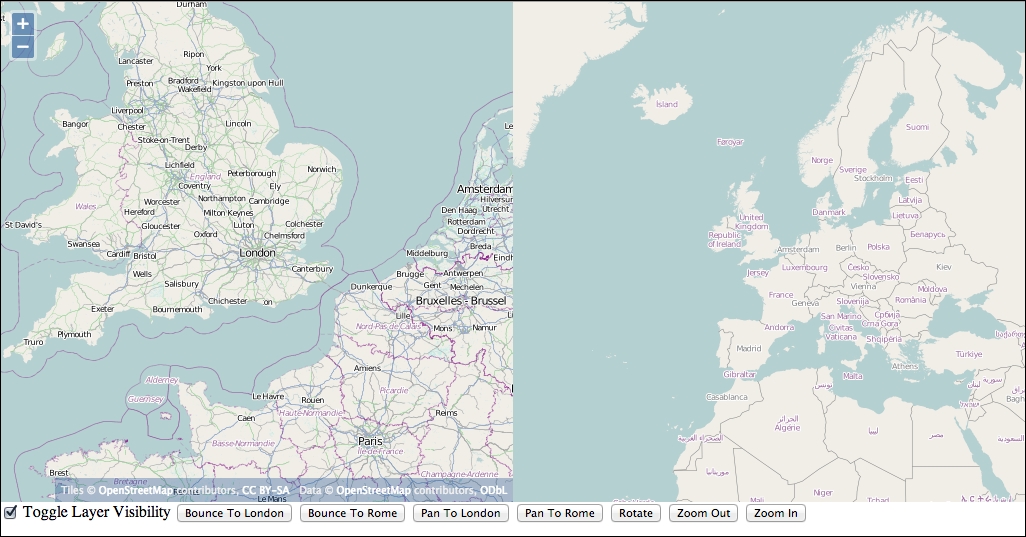

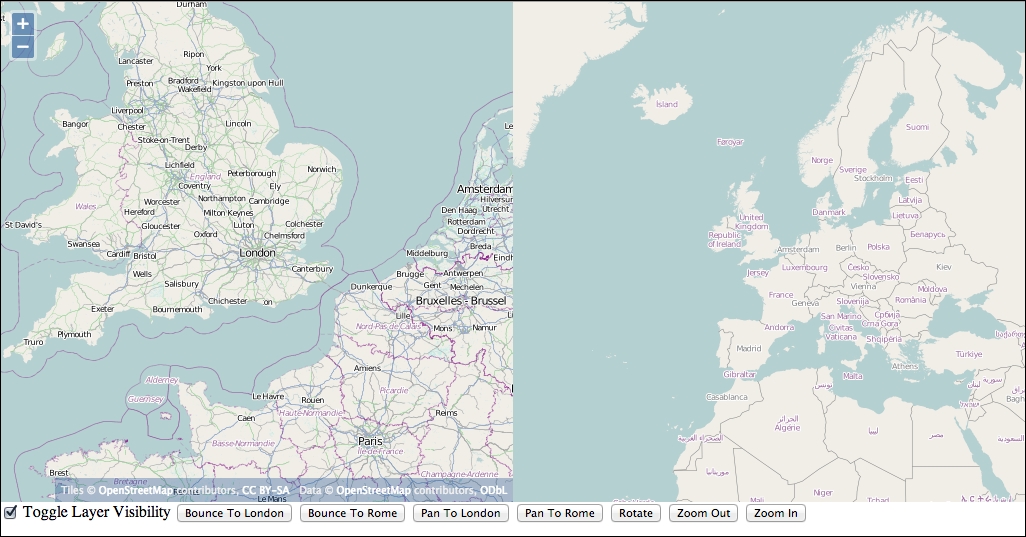

If you try to interact with the map, you'll notice something immediately—you can't click and drag to pan. Instead, if you hold down the Shift key while clicking and dragging, you'll get a whole new behavior. We've also lost the zoom in and out buttons at the top left corner, and the attribution icon in the bottom right corner, but there is a new button in the top-right corner. What does it do?

In the first step, we added our boilerplate HTML code for a simple OpenLayers application. This includes standard HTML tags suitable for any web page, and also includes the OpenLayers CSS and JavaScript files.

Next, we started creating instances of various OpenLayers components to use with our map. The first one was a layer that renders tiles from the OpenStreetMap tile servers. Next, we created an interaction called DragRotateAndZoom. This interaction has no visible element, but rather is triggered by holding down the Shift key while dragging the map. As the name suggests, this interaction will rotate and zoom the map in response to dragging the mouse cursor. Then we created a control called FullScreen. Again, the name gives away what it does—launches the web page into fullscreen mode. Because it is a control, it has a button that is clicked to activate its behavior. Next, we created an overlay, which displays an HTML element at a specific geographic location. Finally, we created the view, giving it the same center as the position we provided to the overlay.

The last step is to tie it all together with the Map class object by passing all our components as part of the constructor. We'll look at the Map class's constructor in more detail in Chapter 3, Charting the Map Class but for now, it's enough to know that we can provide arrays of layers, interactions, controls, and overlays as options, and the Map class will know what to do with them.

We saw that by providing our own set of interactions and controls; we changed the default behavior of an OpenLayers application. This is because the Map class has a default set of interactions and controls that it creates when they are not explicitly provided as options to the constructor. There are two ways we can restore the default behavior and add our new components as well.

The first way is to use helper functions provided by OpenLayers to obtain the collection of default interactions and default controls and extend those with our new components. We will do something like this (this example is not complete as the Map class is missing a view):

// create our interaction

var interaction = new ol.interaction.DragRotateAndZoom();

// get the default interactions and add our new one

var interactions = ol.interaction.defaults().extend([interaction]);

// create our control

var control = new ol.control.FullScreen();

// get the default controls and add our new one

var controls = ol.control.defaults().extend([control]);

// create the map and pass in the extended set of interactions and controls

var map = new ol.Map({

interactions: interactions,

controls: controls

});The second method is to add them to the map after calling the constructor, for instance, (again, this example is not complete):

var interaction = new ol.interaction.DragRotateAndZoom(); var control = new ol.control.FullScreen(); var map = new ol.Map(); map.addInteraction(interaction); map.addControl(control);

The advantage of the first method (passing constructor options) is that it gives you complete control over which interactions and controls are in use, while the second method (adding them after creating the map) has the advantage of being simpler if you want to add to the existing set of interactions and controls.

In many parts of OpenLayers, you will discover that there are multiple ways of accomplishing a given task. This is part of the design of the OpenLayers library and provides developers with the option to write code in a way that makes most sense for them.

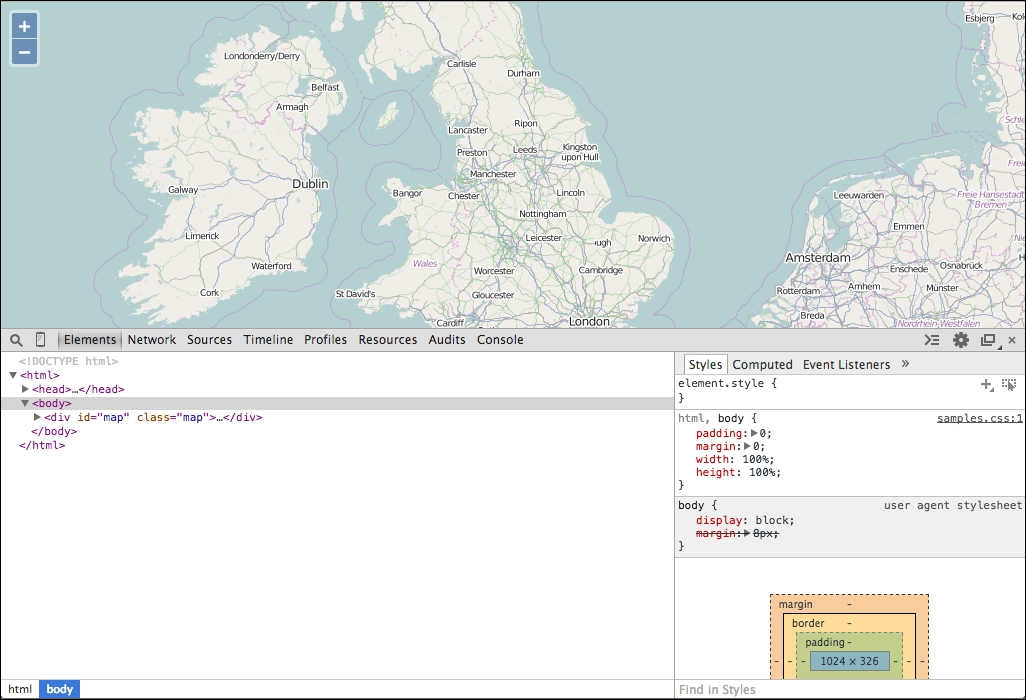

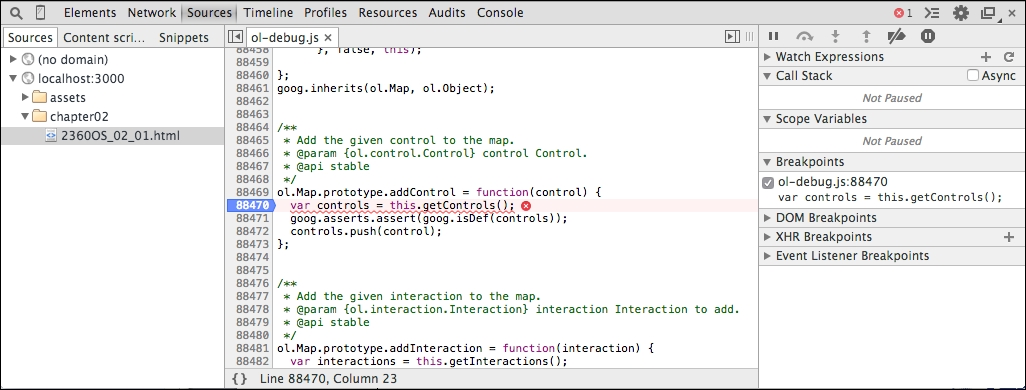

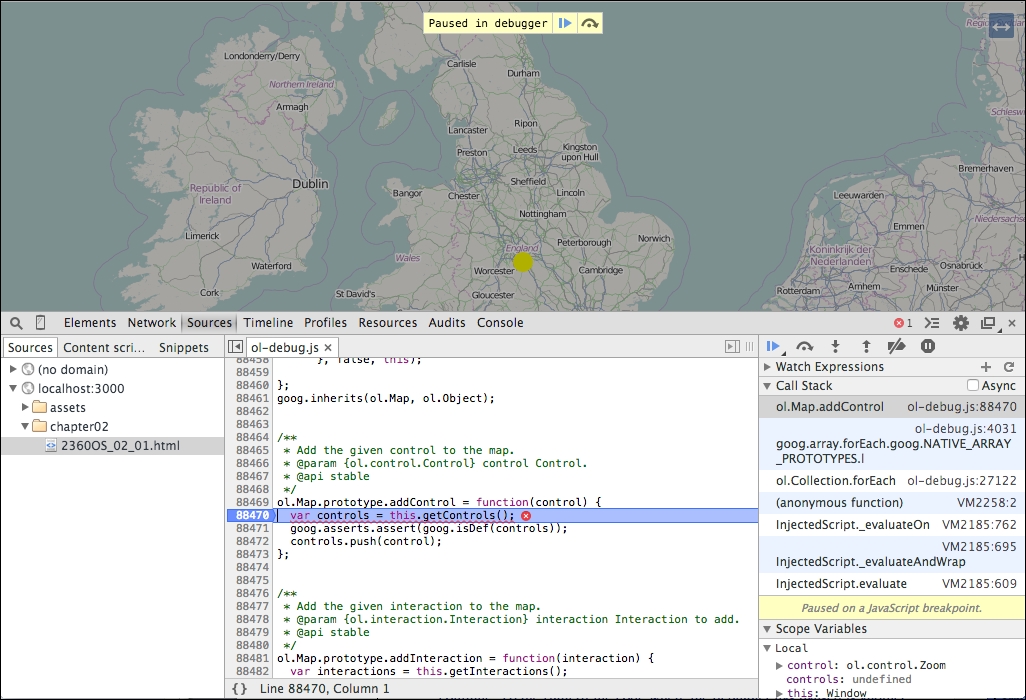

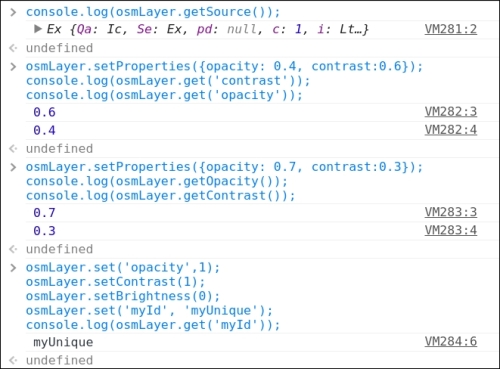

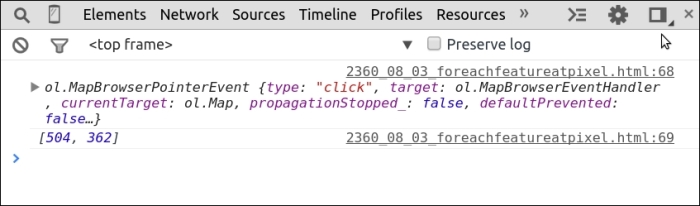

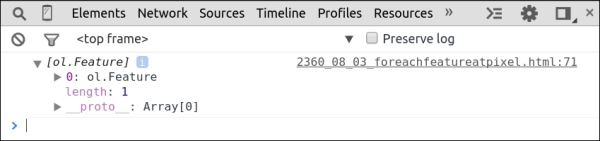

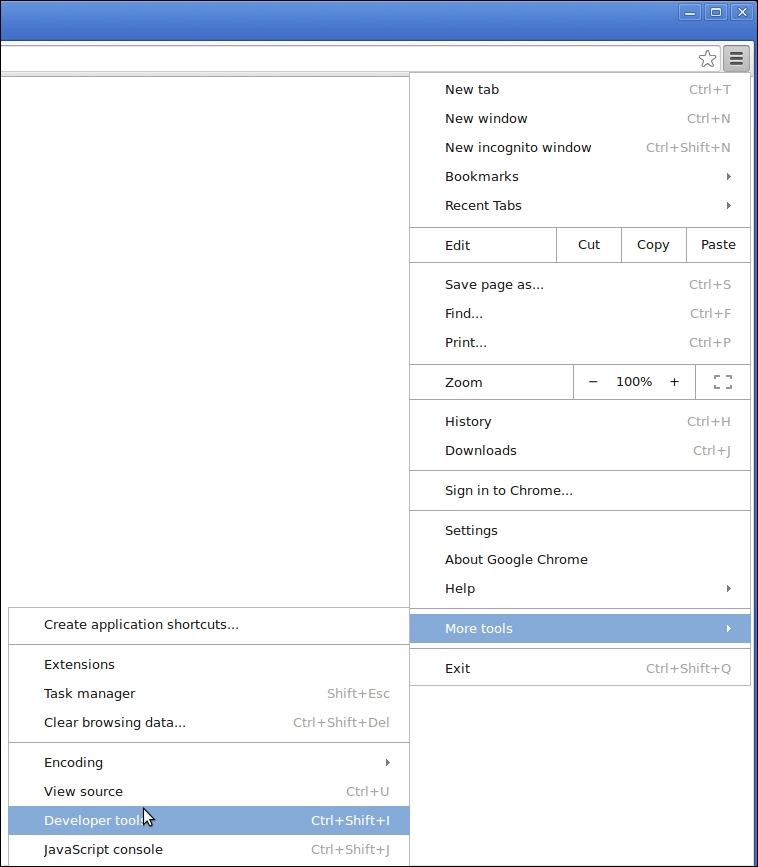

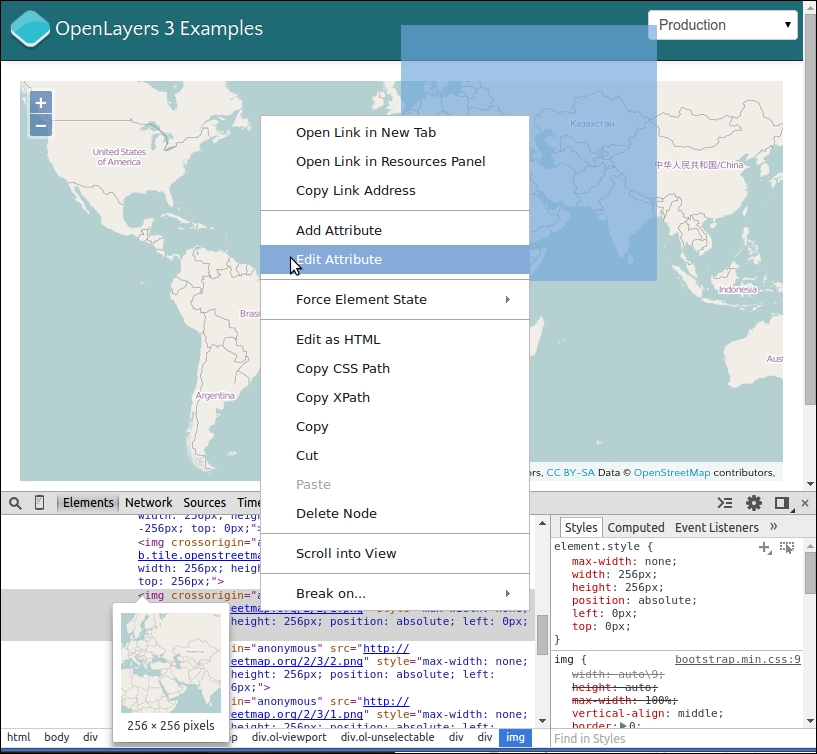

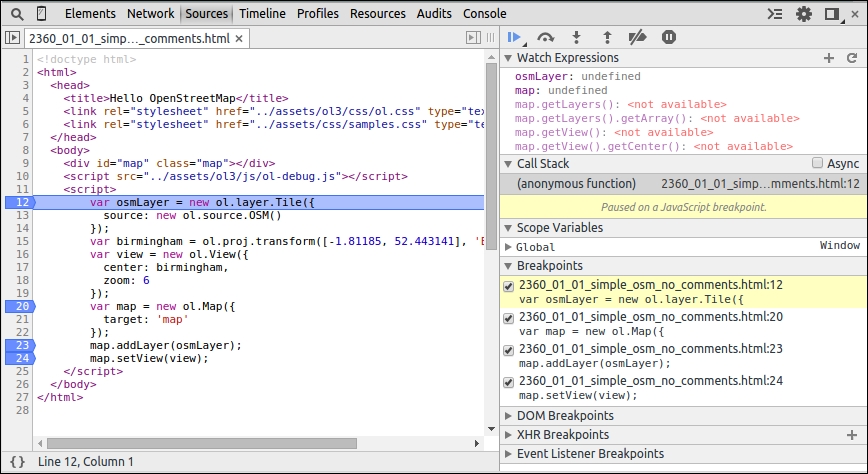

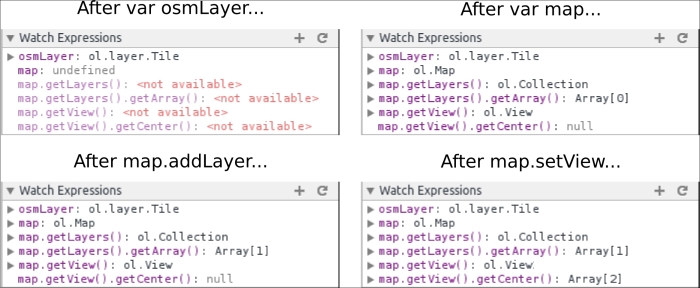

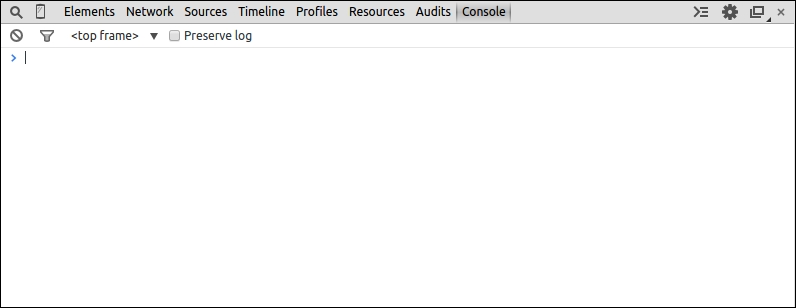

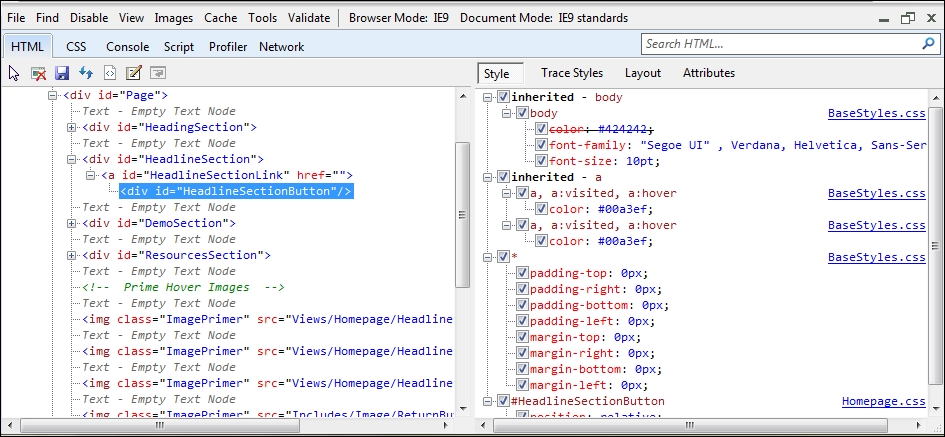

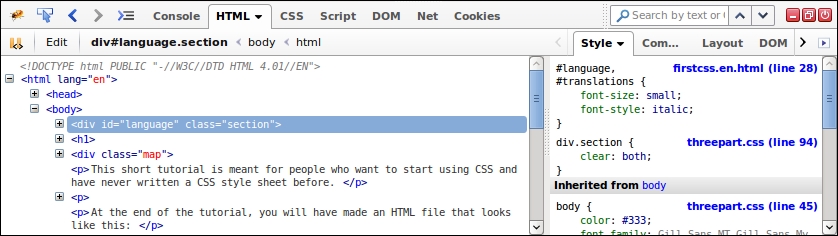

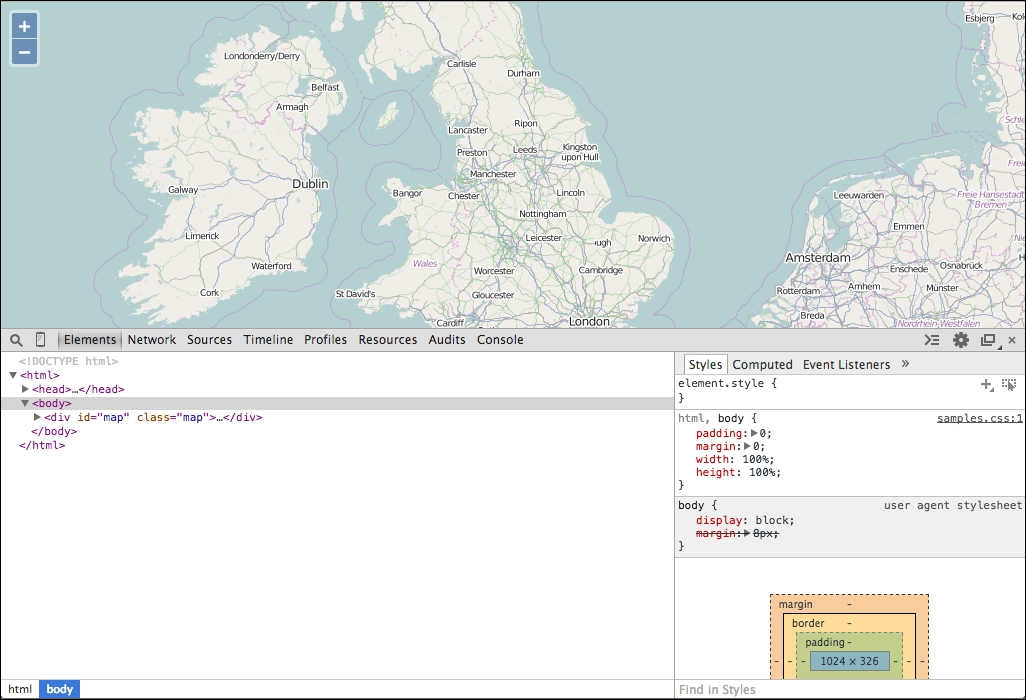

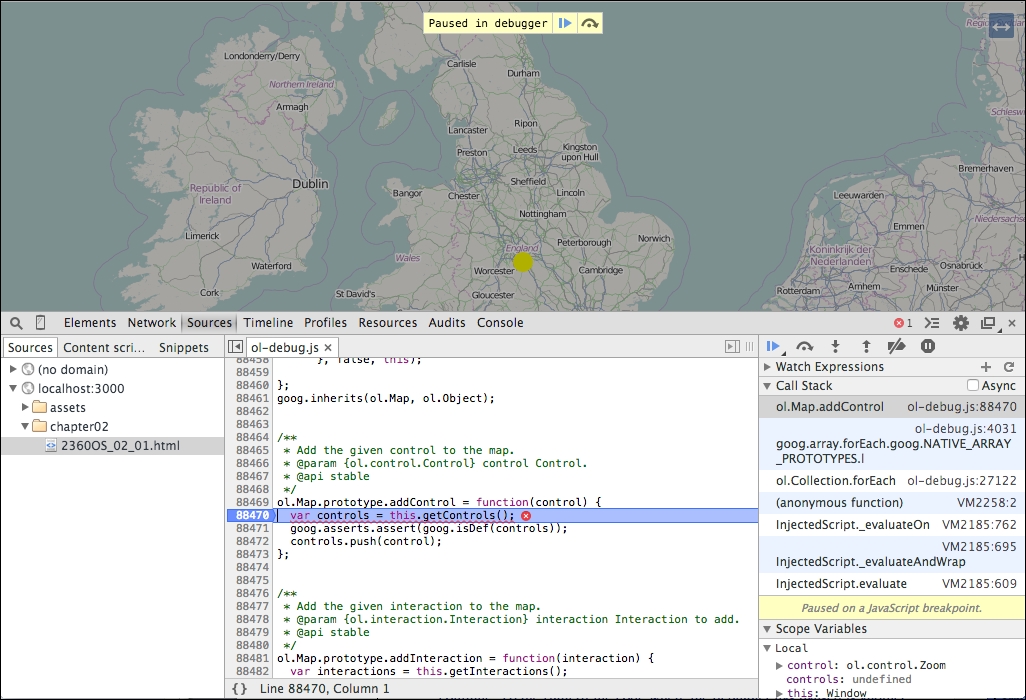

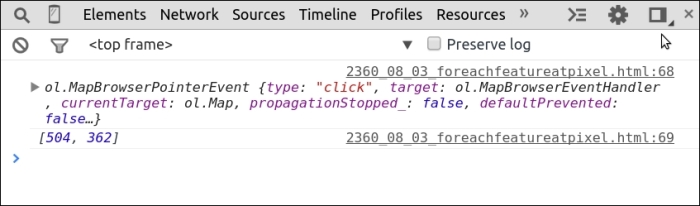

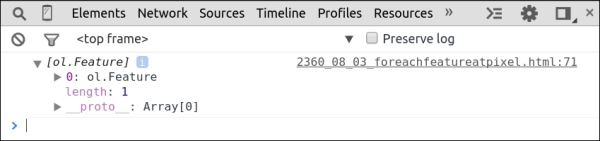

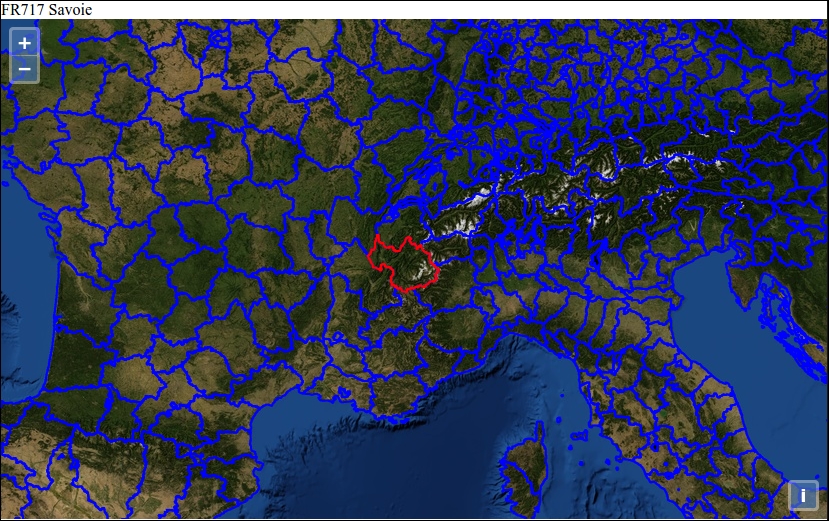

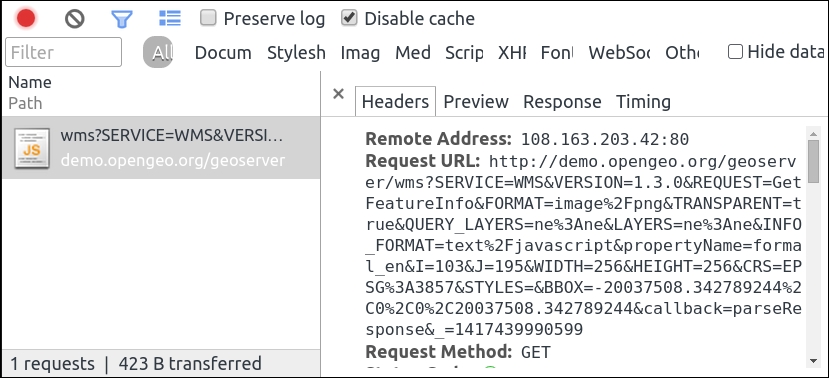

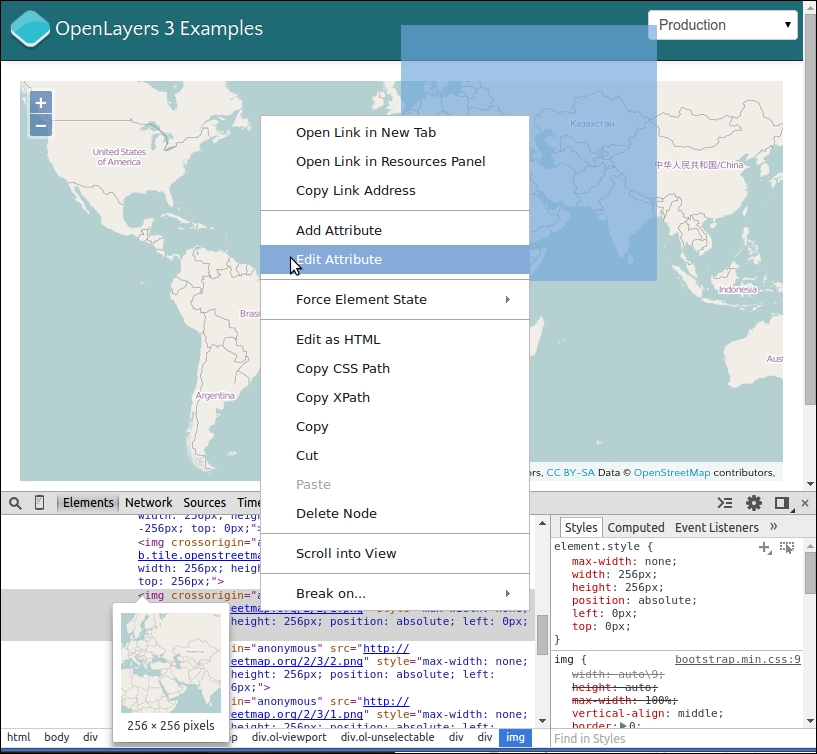

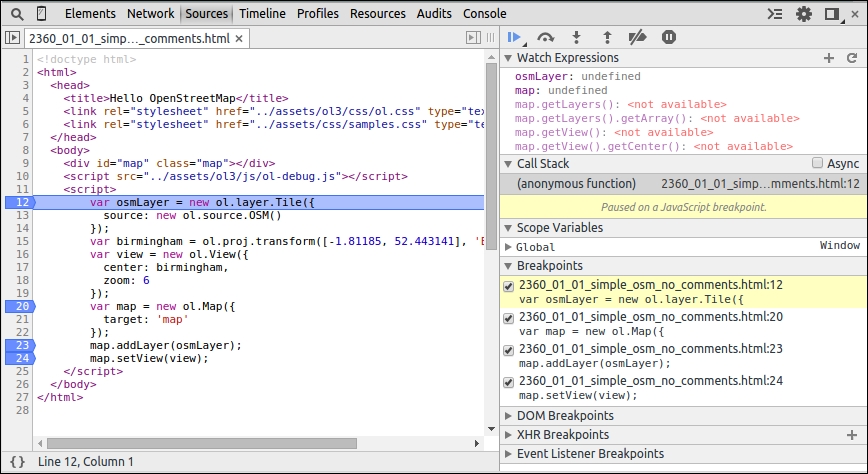

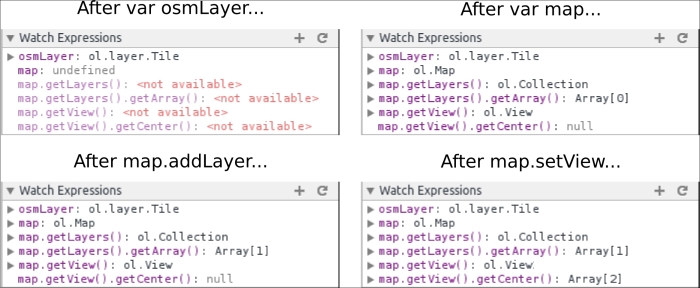

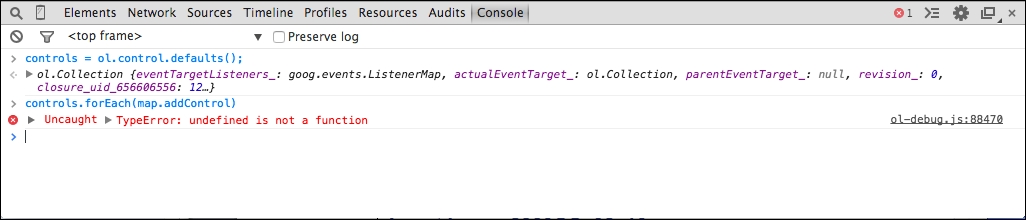

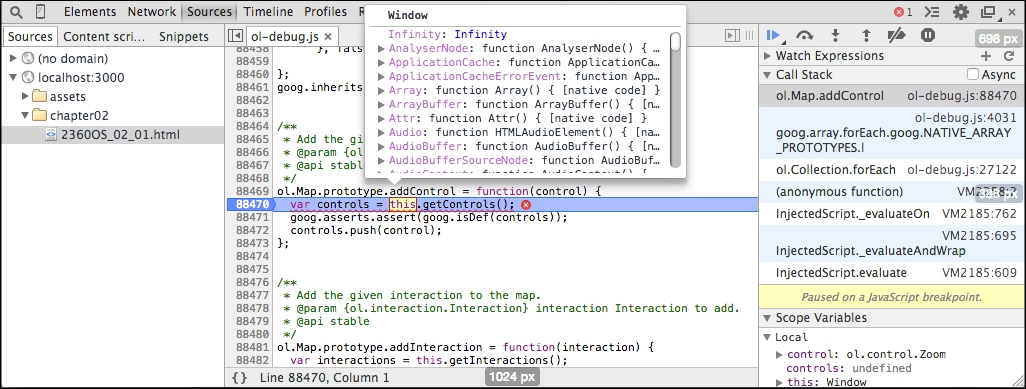

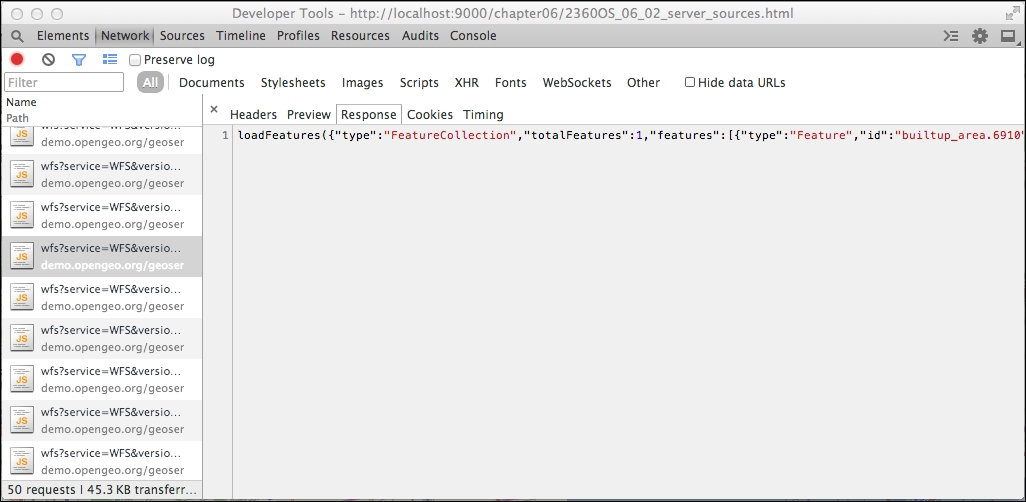

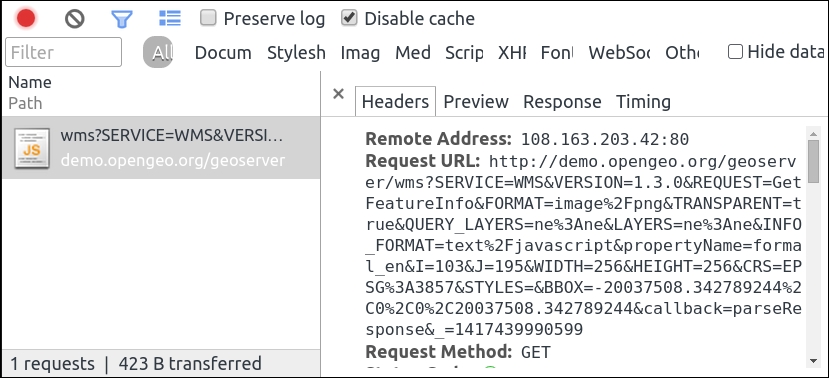

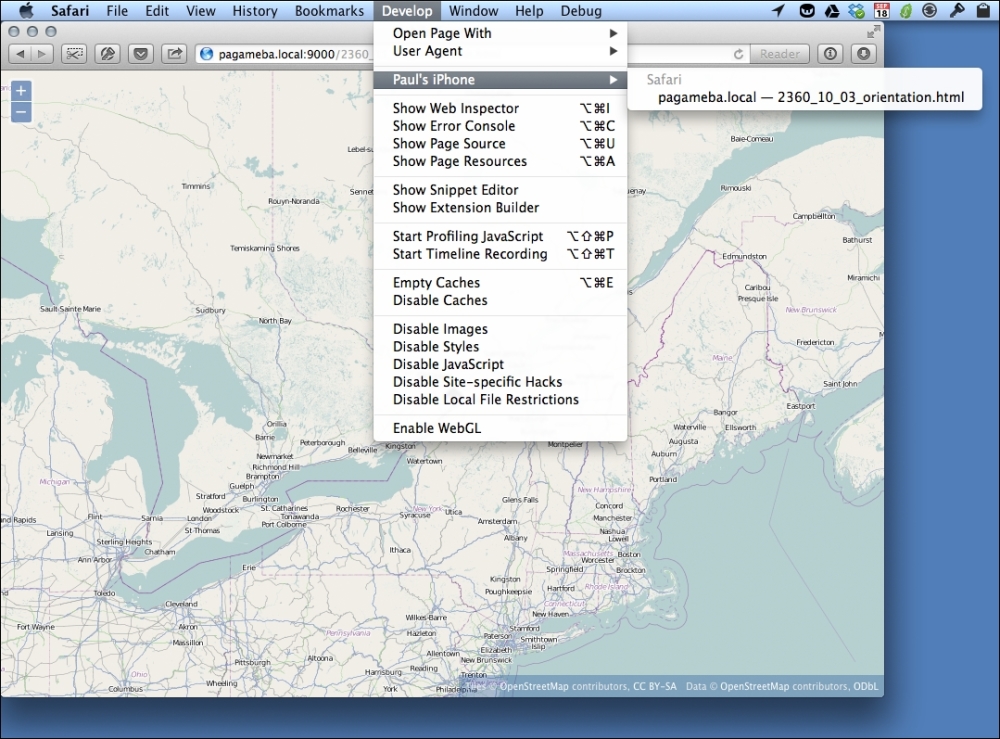

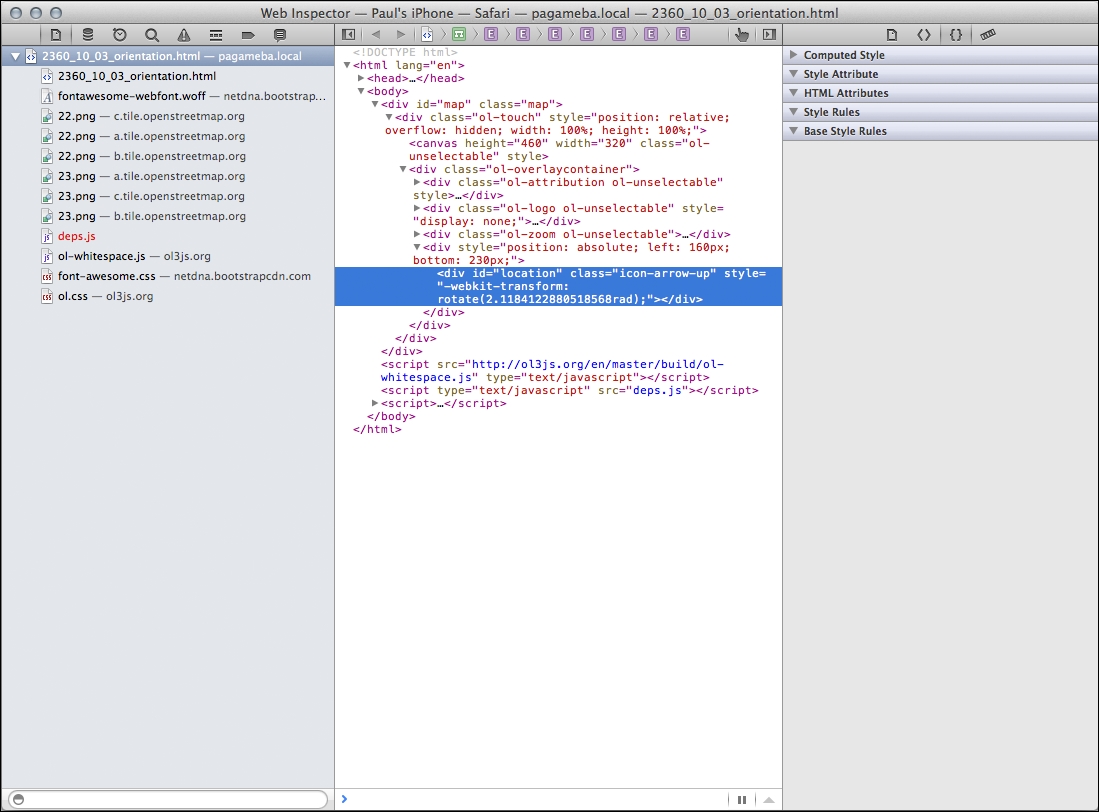

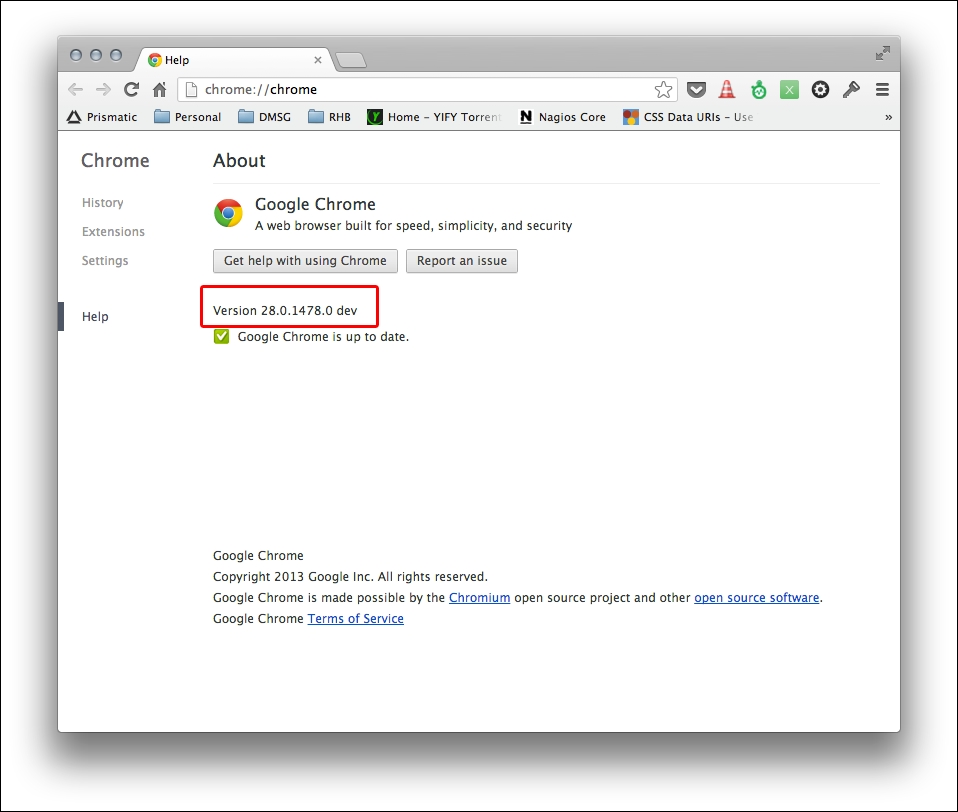

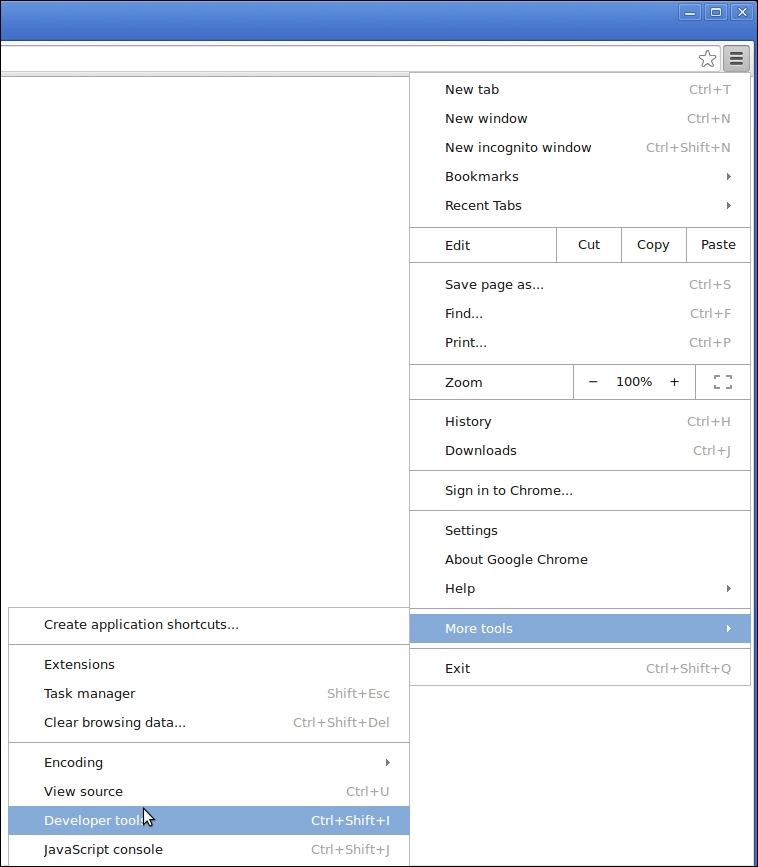

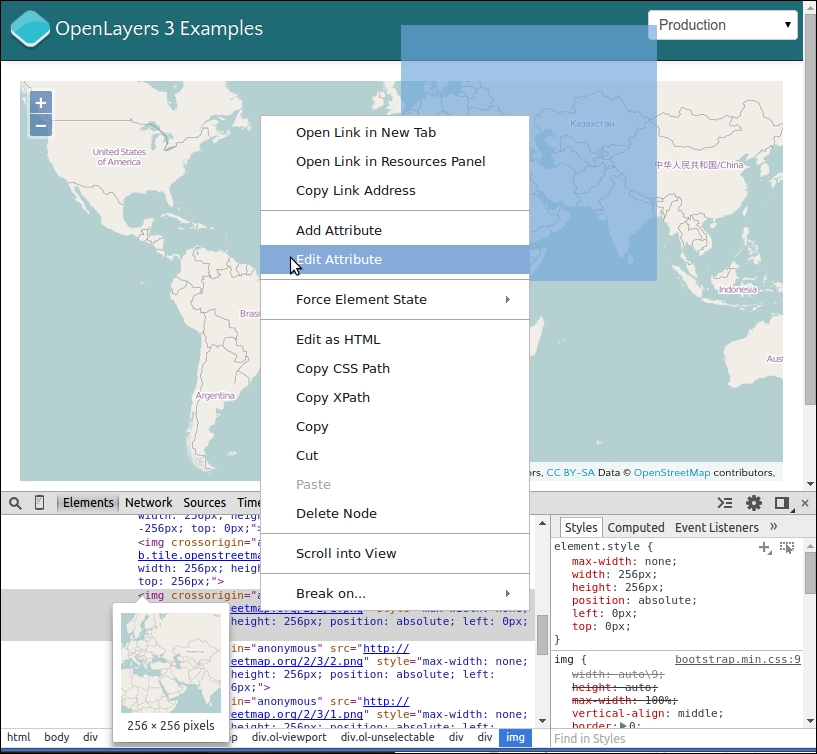

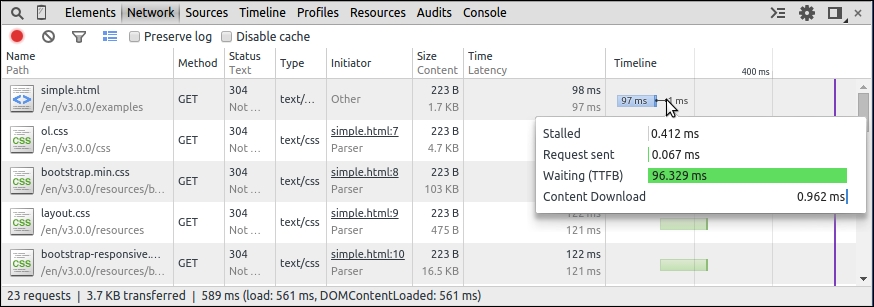

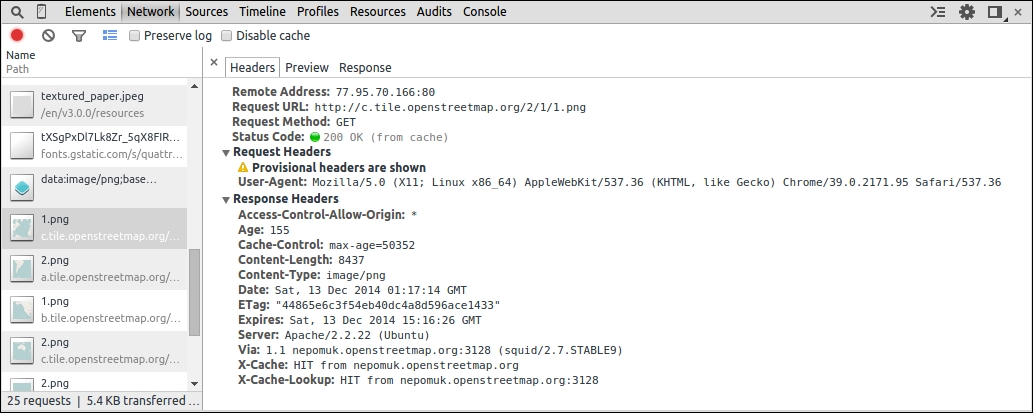

We noted at the end of the previous example that the map wasn't working normally. We replaced the default controls and interactions and so the default behavior wasn't present any more. Let's take a moment to try to fix this. In many cases, mistakes or oversights in our code will produce unexpected results. Web developers have a number of tools available to help them diagnose and fix these problems. In this example, we'll work with the Developer Tools available in the Chrome browser. Similar tools exist for all major browsers; if you are not using Chrome, you should still be able to follow along using your browser's Developer Tools. With the previous example open in your browser, let's get started:

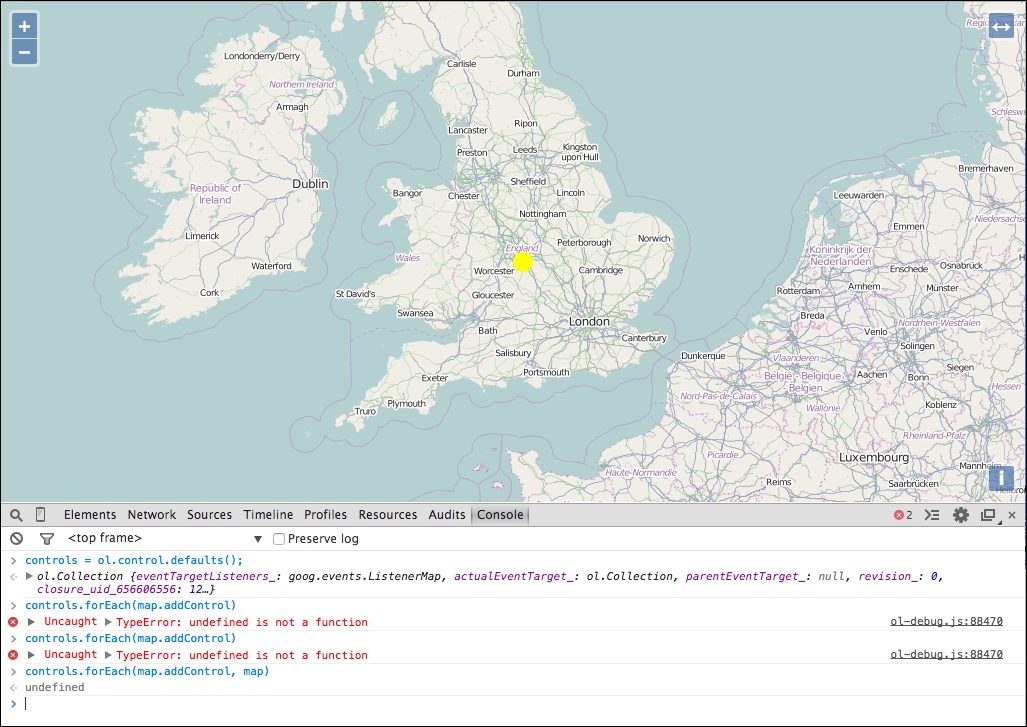

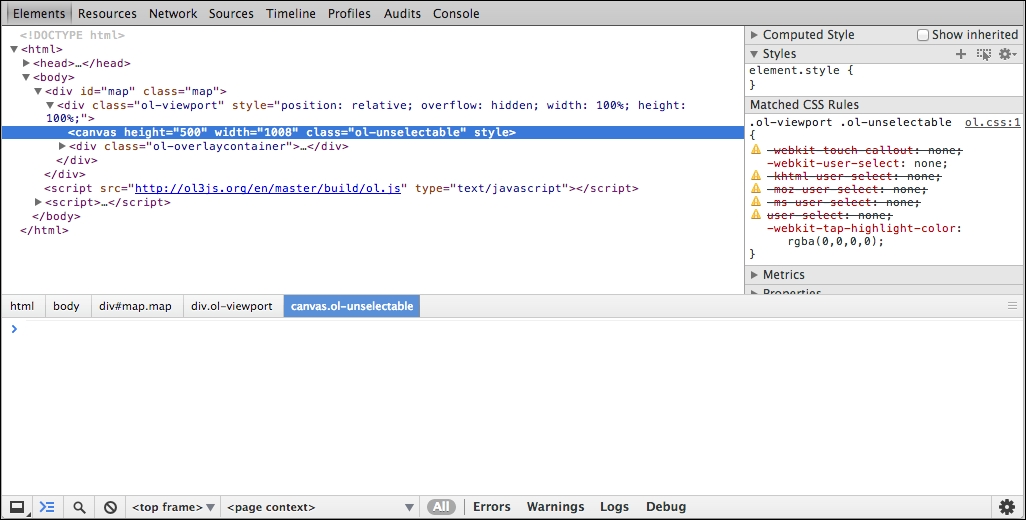

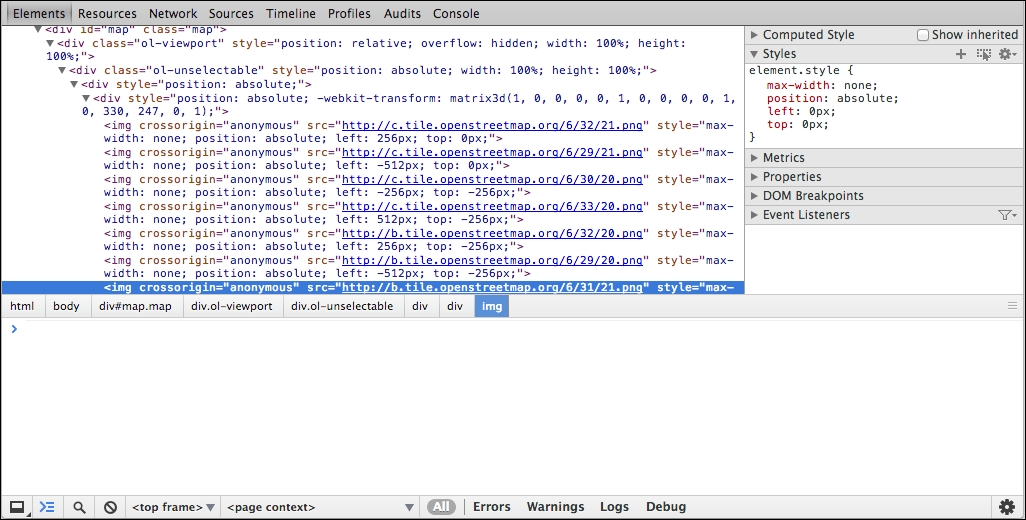

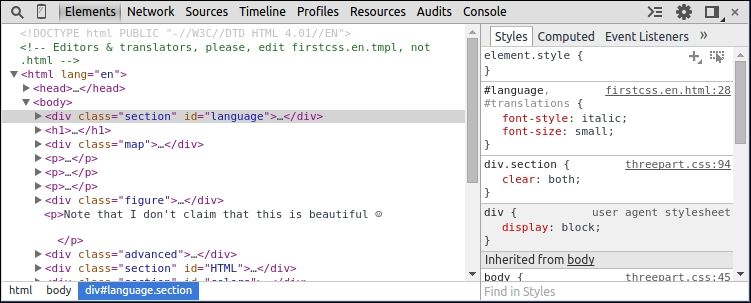

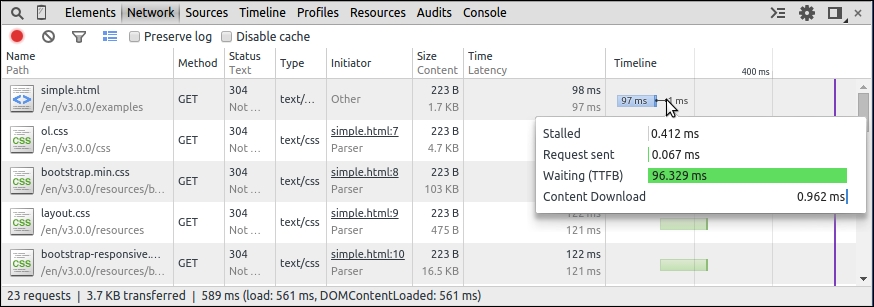

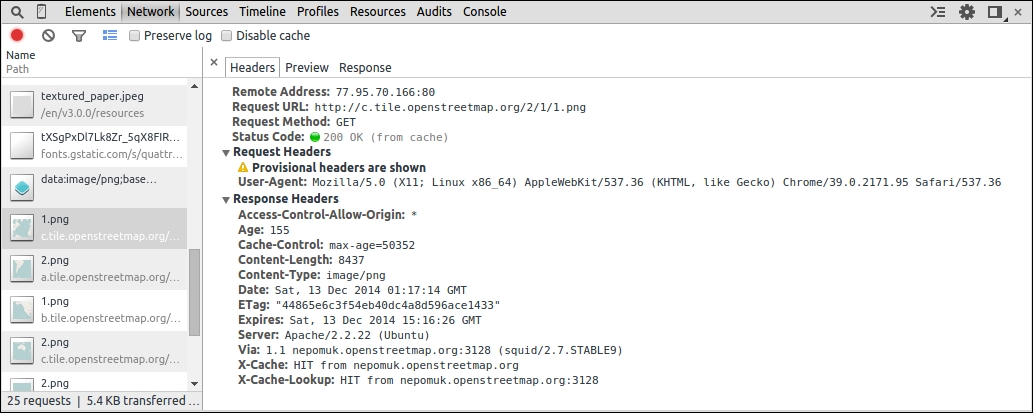

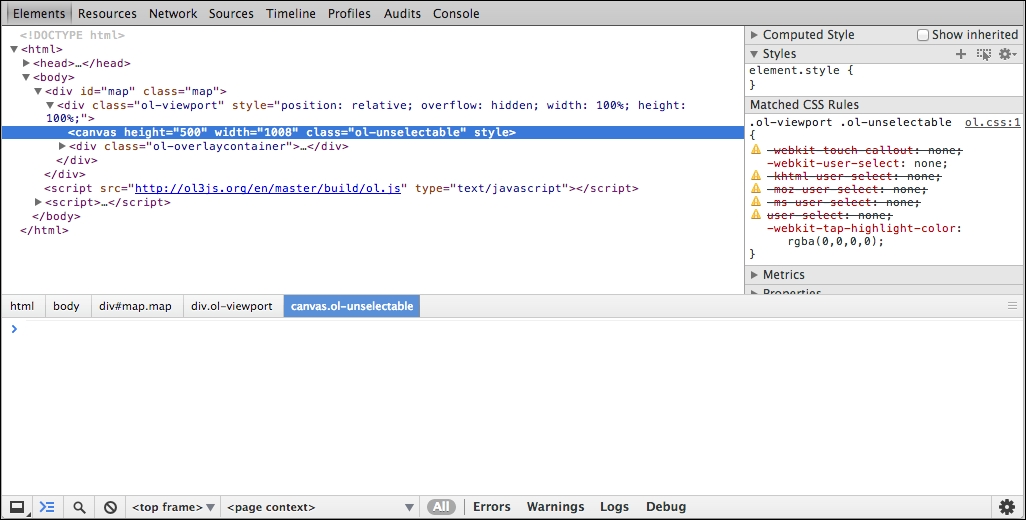

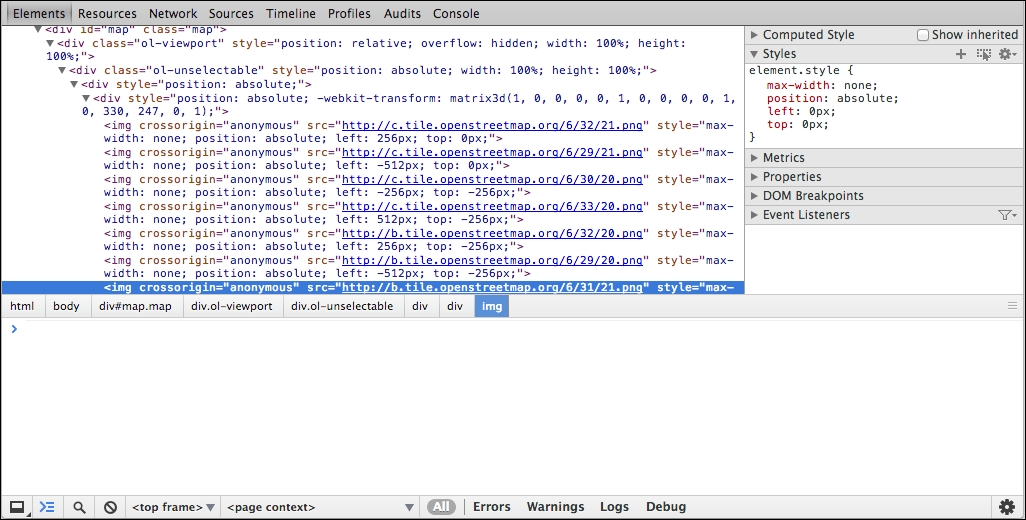

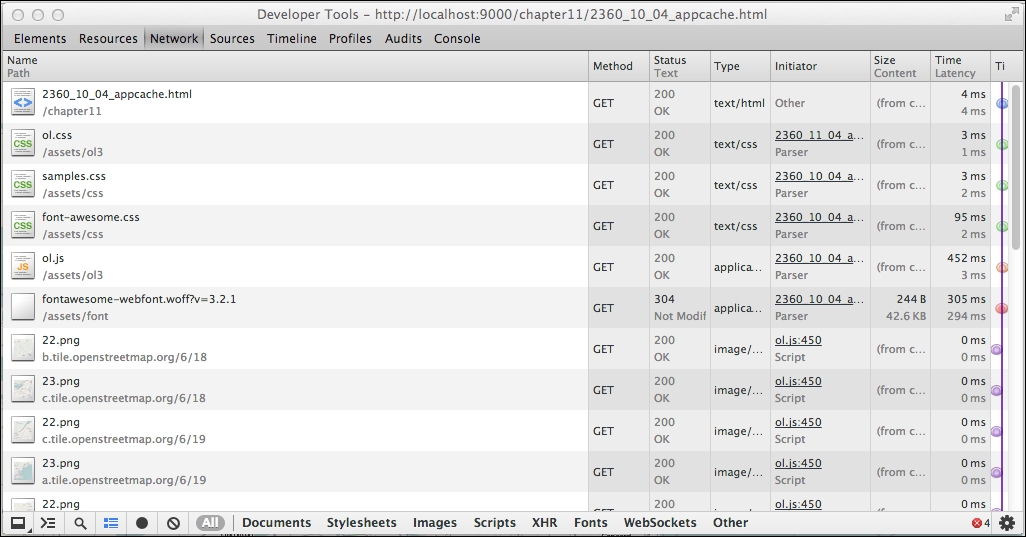

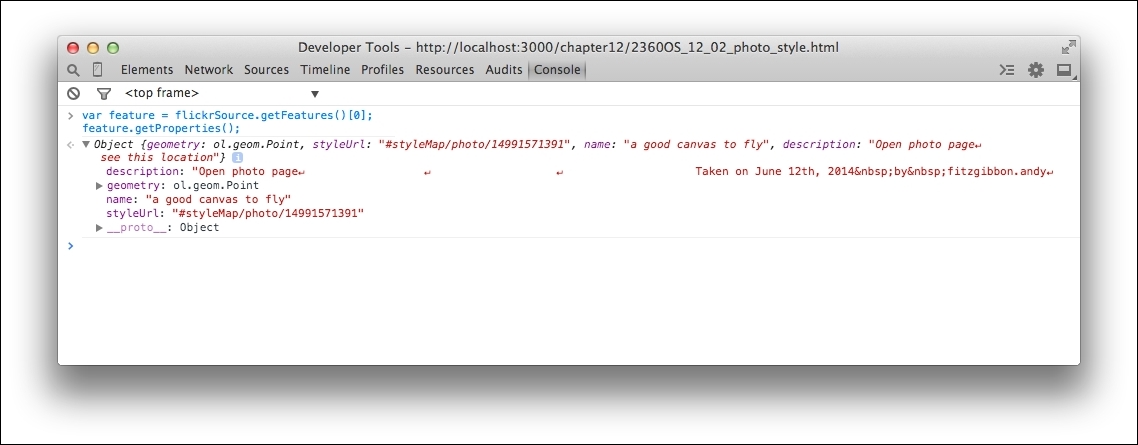

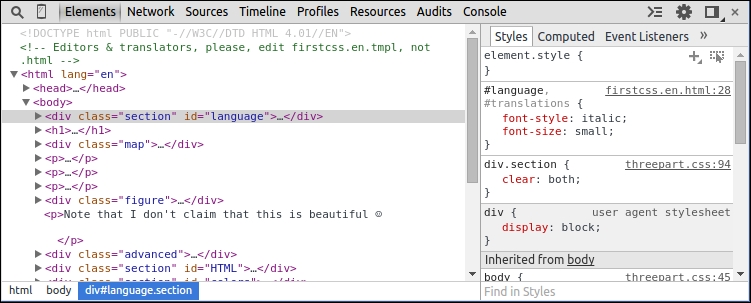

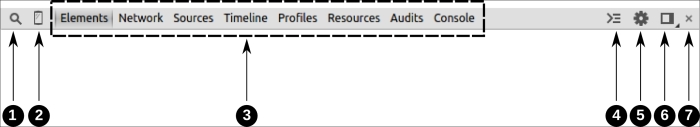

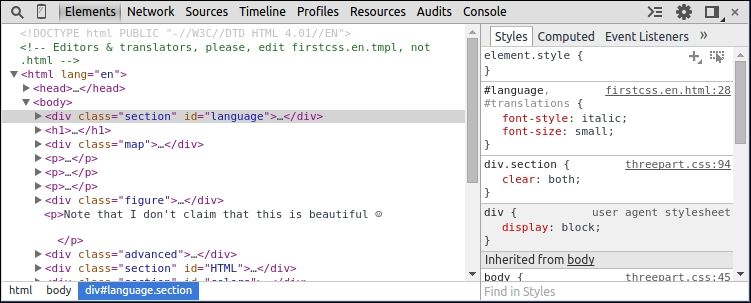

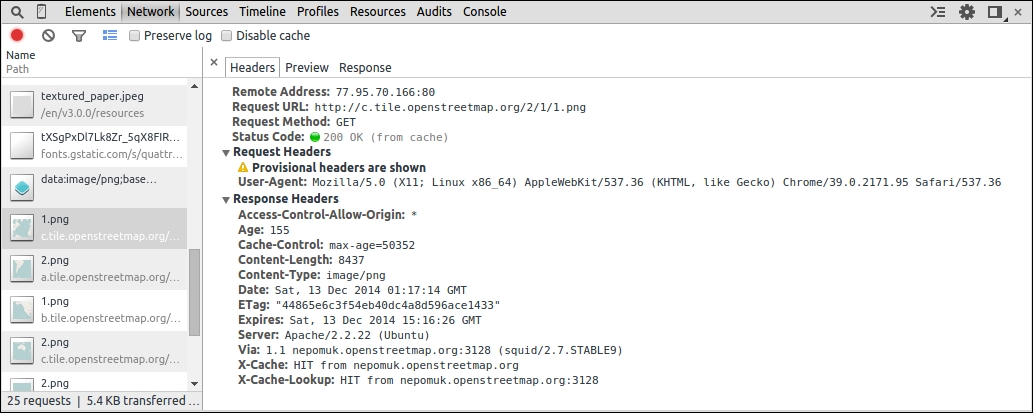

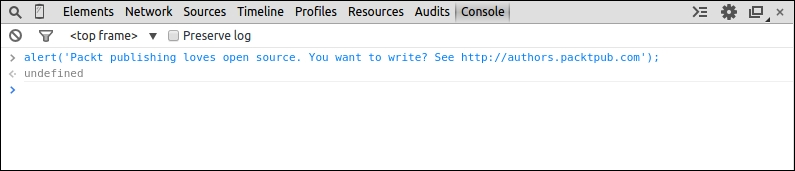

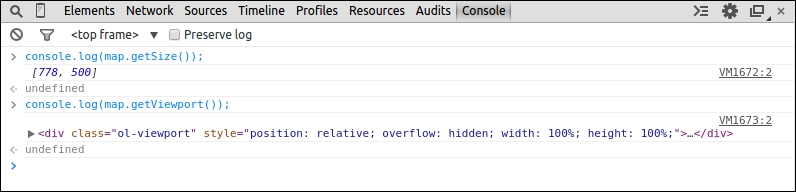

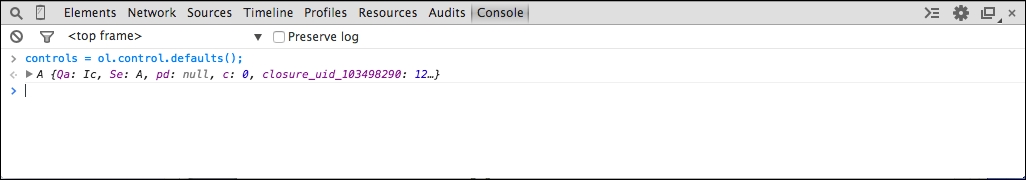

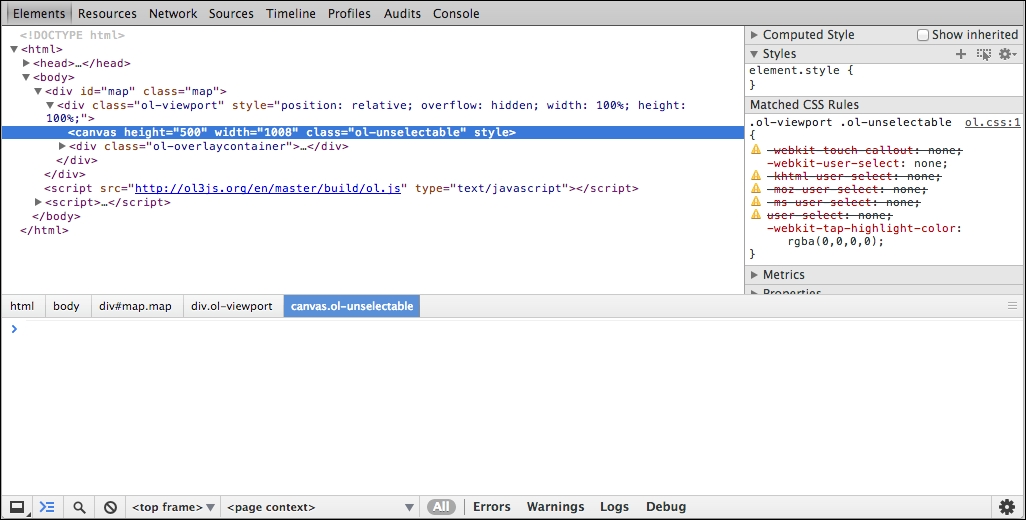

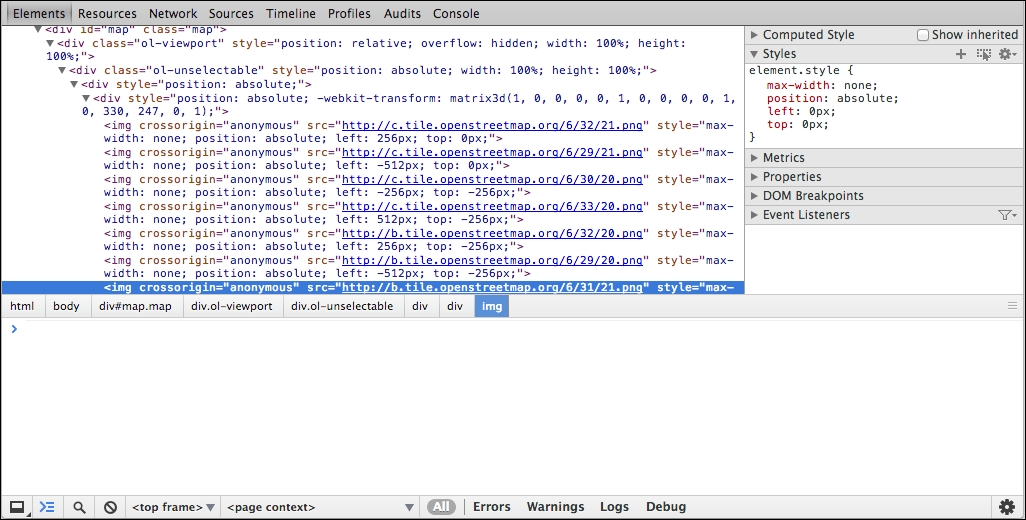

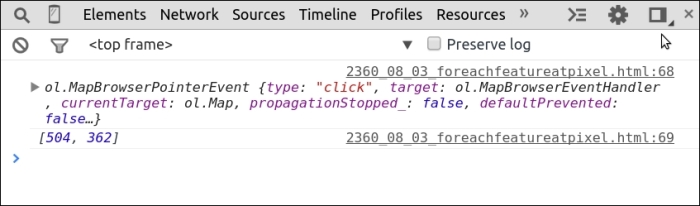

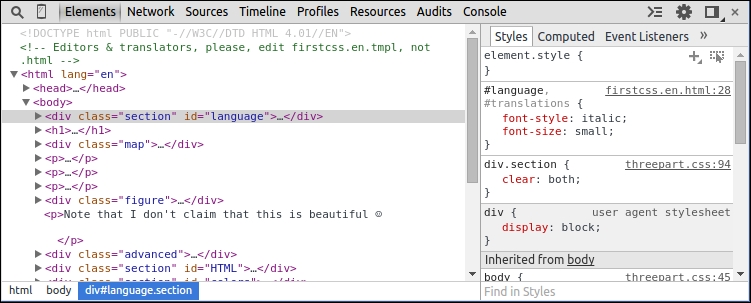

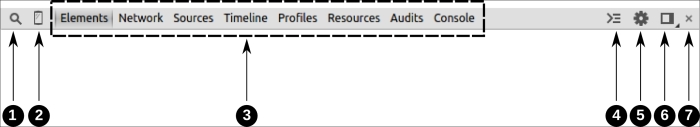

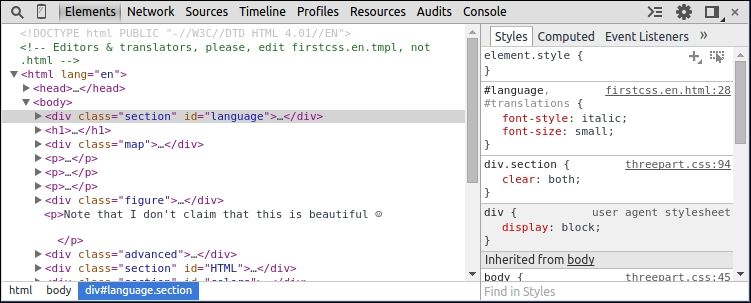

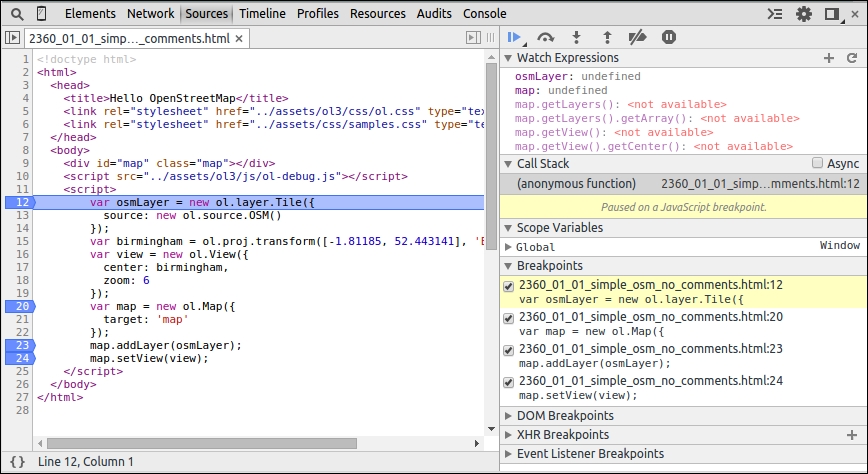

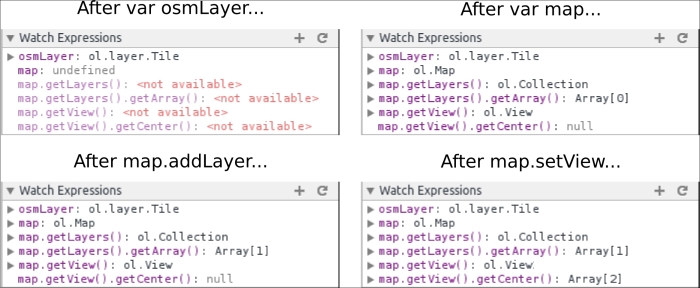

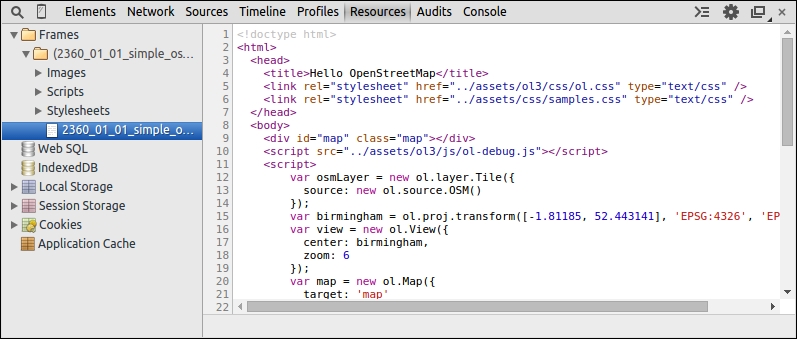

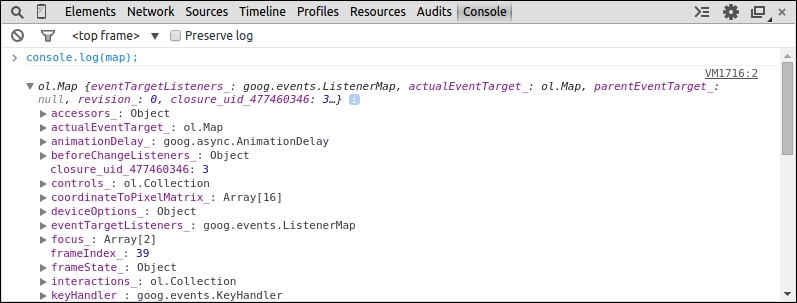

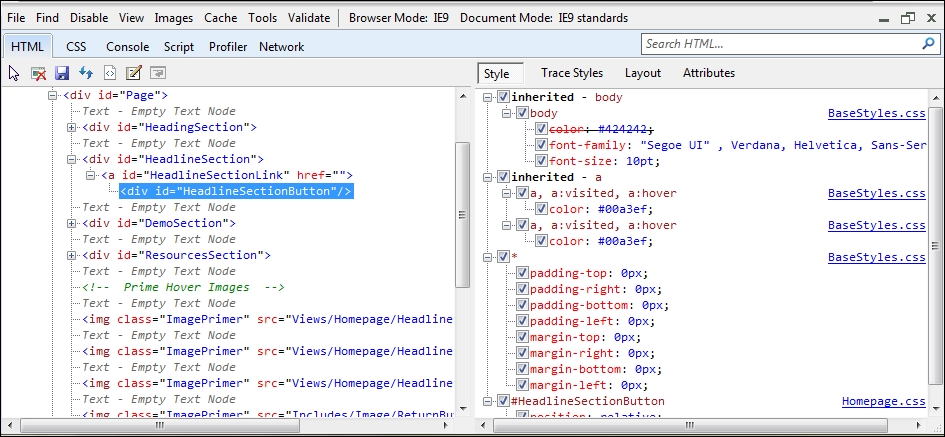

Using any of these methods, a new Developer Tools window will open. By default, the Developer Tools window will be docked to the current tab at the bottom. You can change this by detaching it to a separate window or moving it to one side, but for now, let's keep it at the bottom. It should look something like the following screenshot:

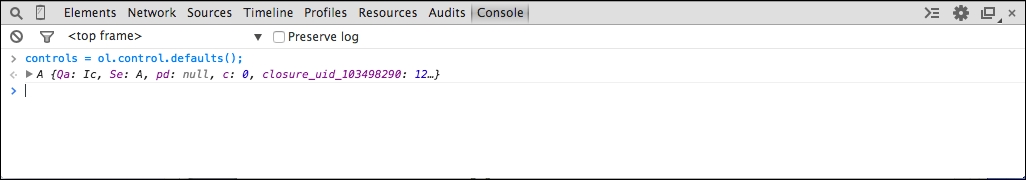

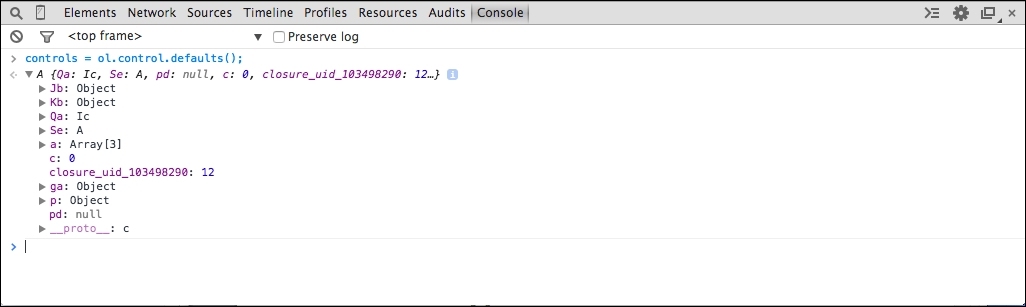

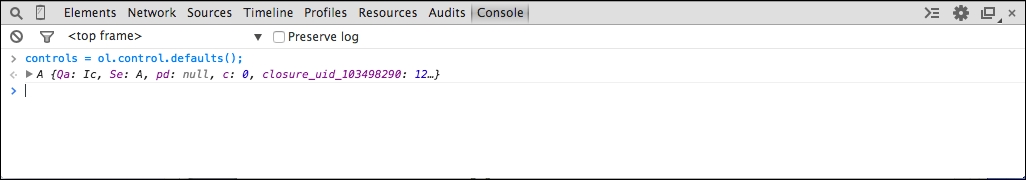

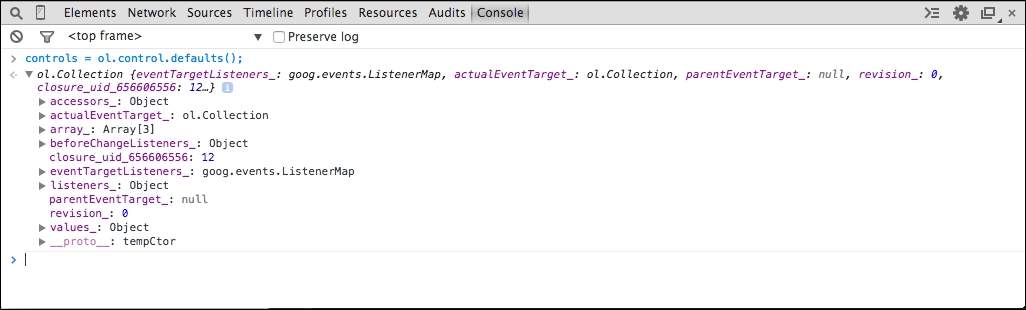

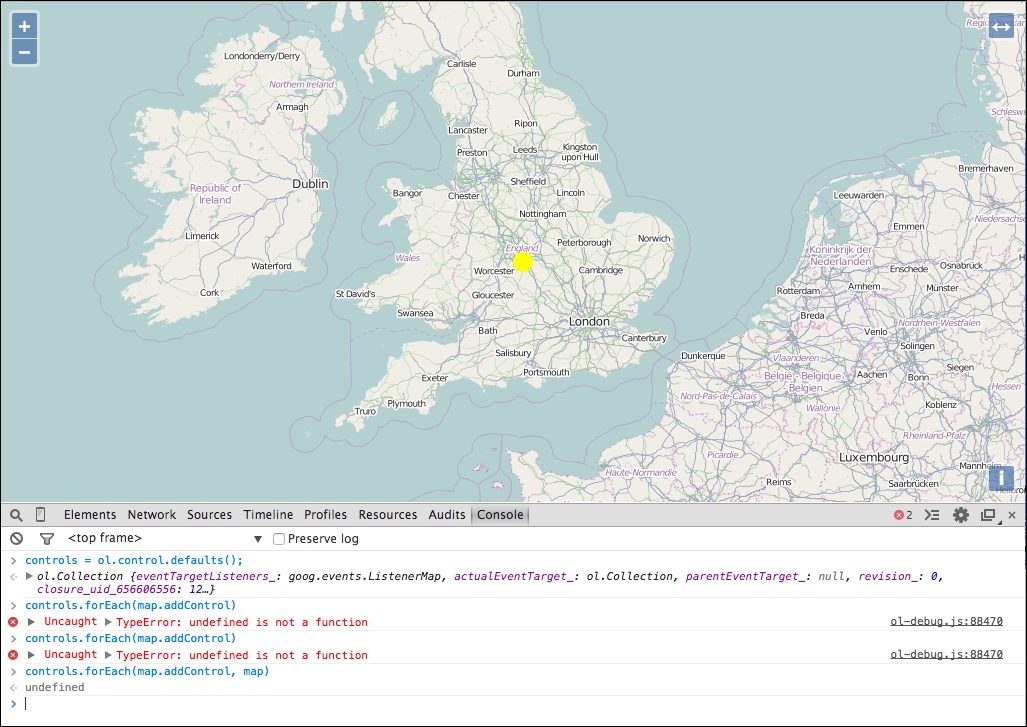

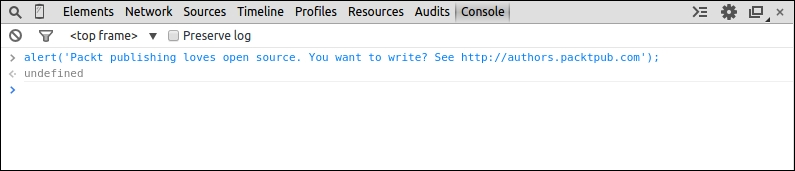

controls = ol.control.defaults();

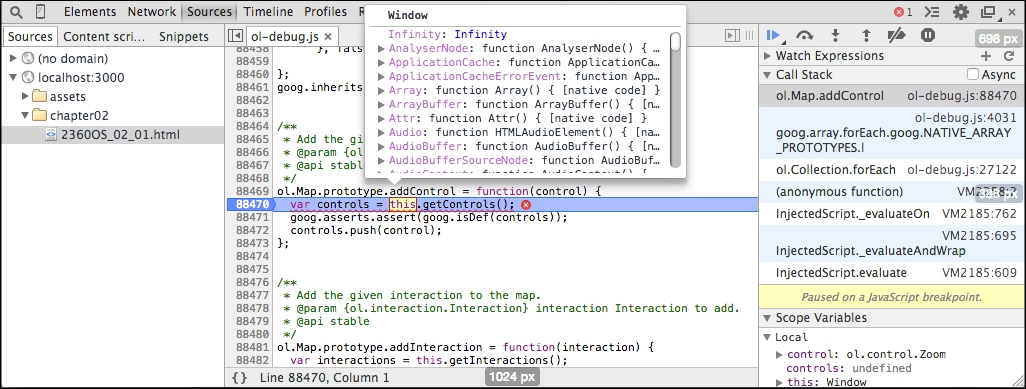

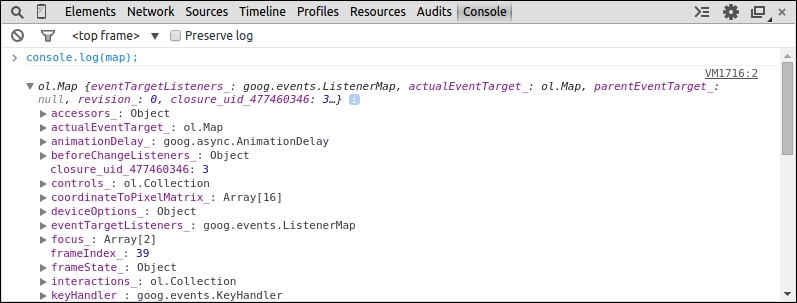

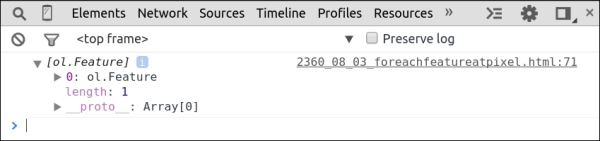

This should output the value that was assigned to the variable controls, something like the following screenshot:

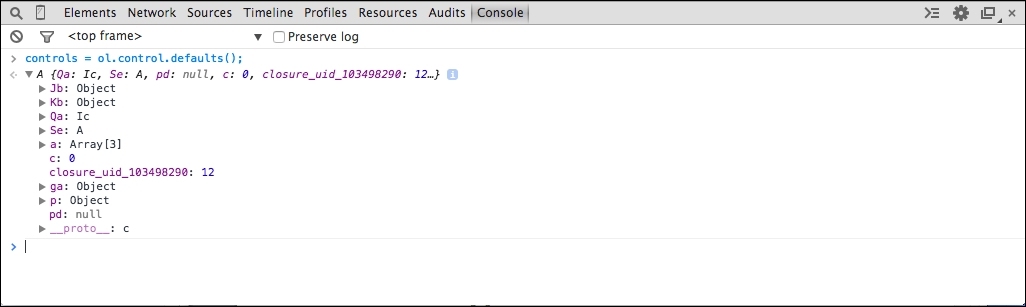

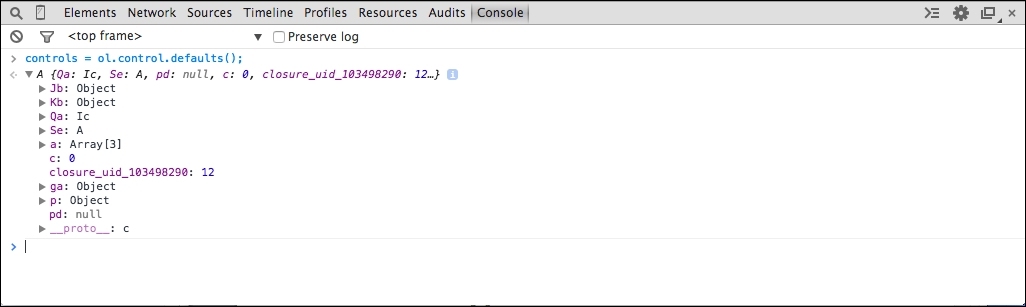

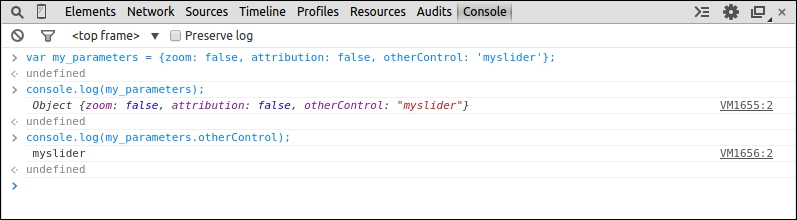

You can click the small triangle next to the line of output to expose properties of the object, like the following screenshot:

We can't even tell what kind of object this is! Let's fix that first.

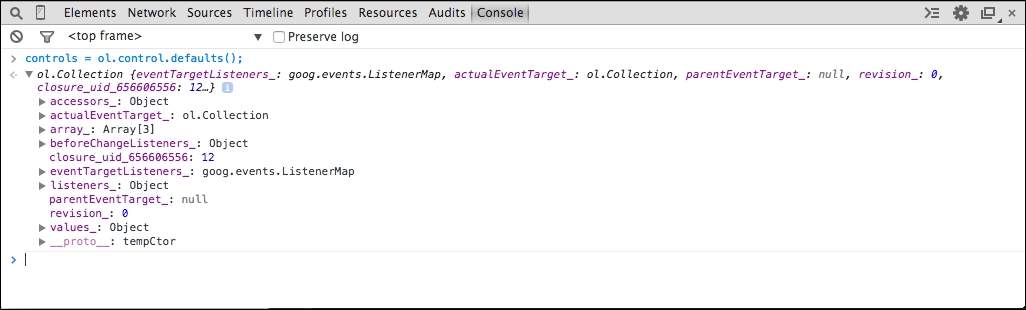

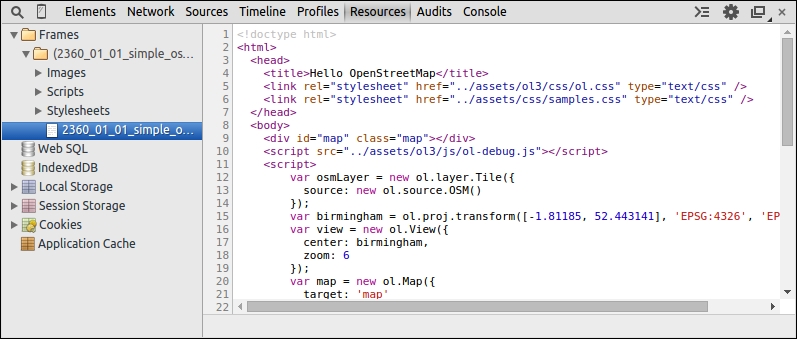

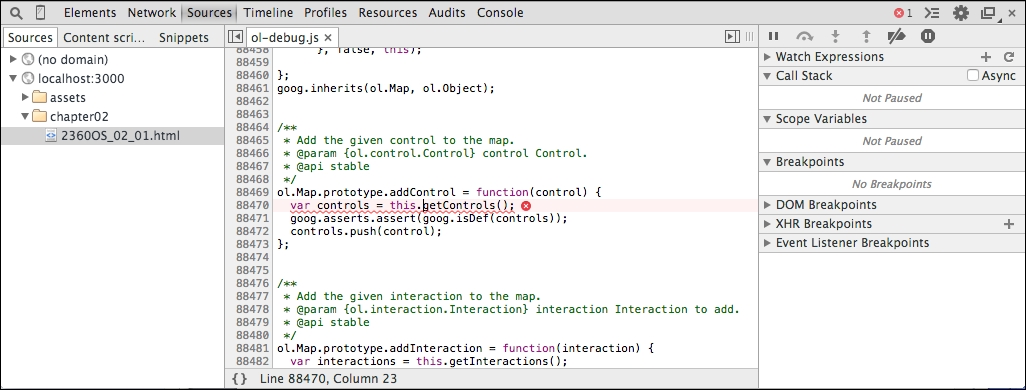

ol.js to load the debug version ol-debug.js:<script src="../assets/ol3/js/ol-debug.js"></script>

The build process used to create production and debug versions of OpenLayers is covered in detail in Chapter 11, Creating Web Map Apps and Appendix B, More details on Closure Tools and Code Optimization Techniques.

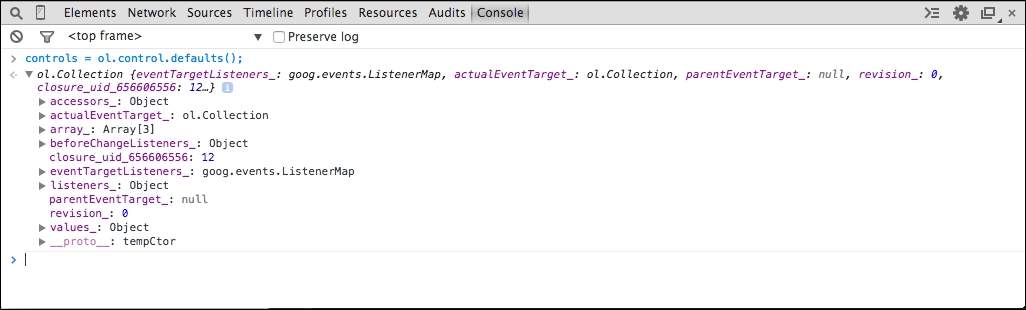

Now, we can see that the controls variable is an instance of ol.Collection and we should be able to add each of the elements of the collection to the map. The line of output expanded, you can see the properties of the collection object.

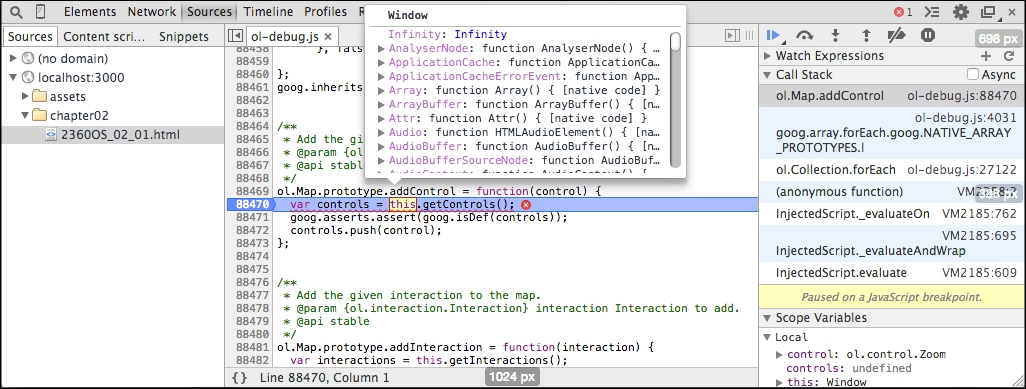

The last entry is labeled __proto__ and has a triangle next to it. The __proto__ property is a special property that shows us an object's prototype, essentially the methods it gains from the class the object was created from. We can explore this property for methods available to be called on the object. Note that the __proto__ property may also have a __proto__ property revealing further methods inherited from other classes in the inheritance hierarchy.

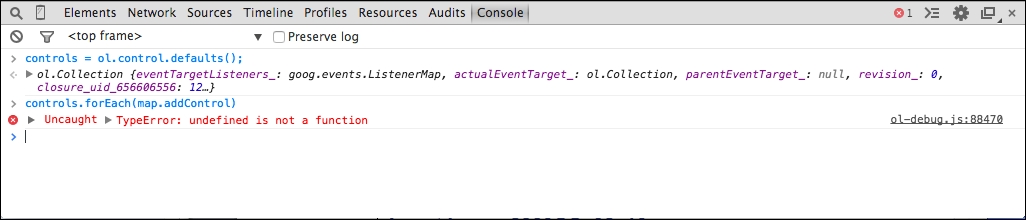

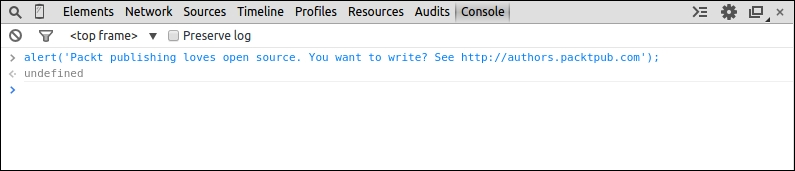

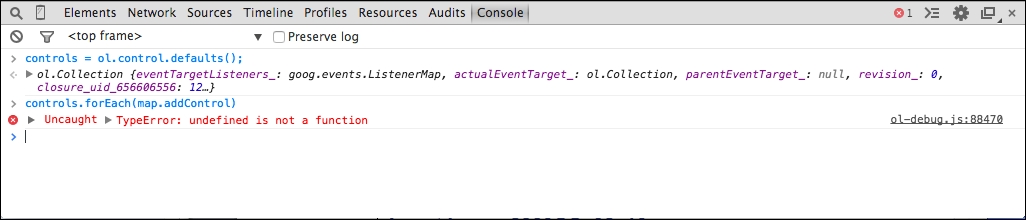

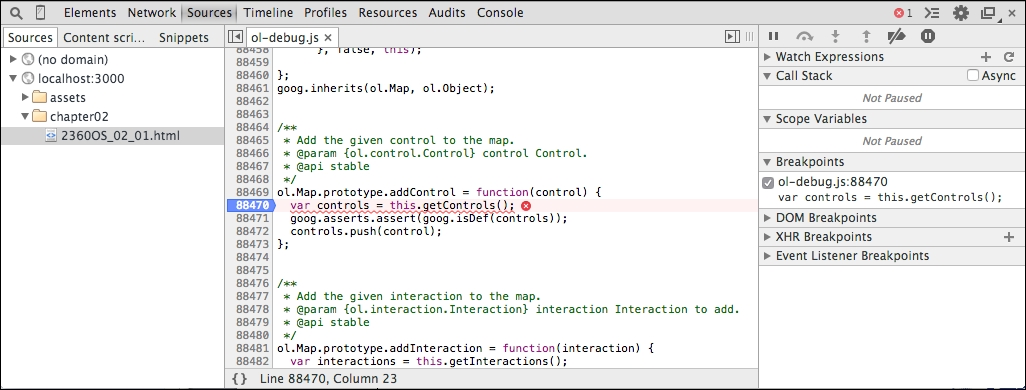

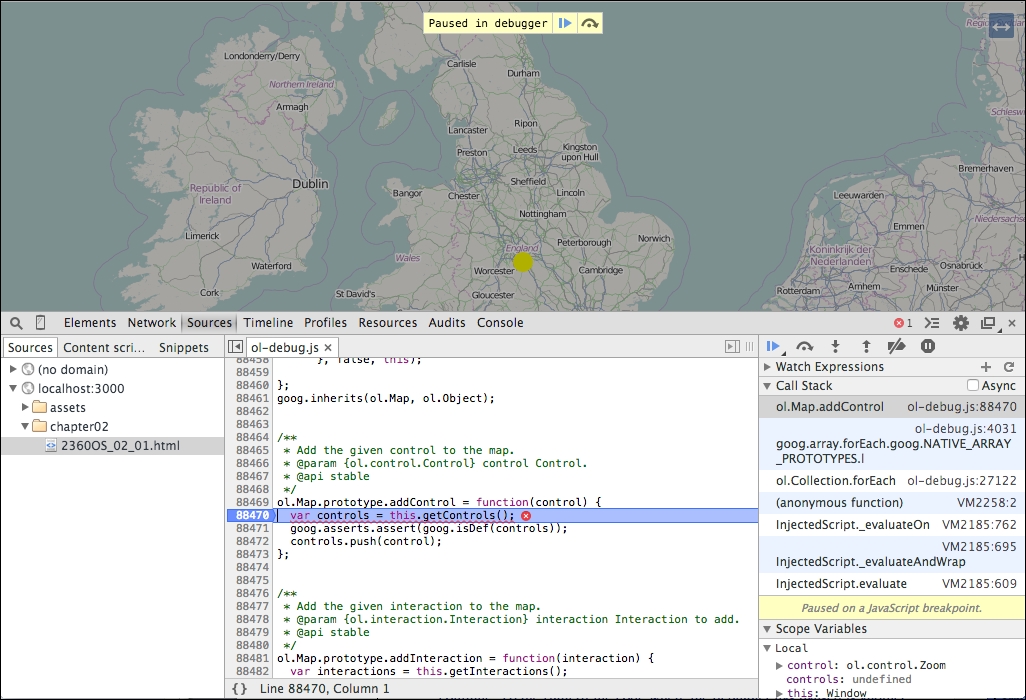

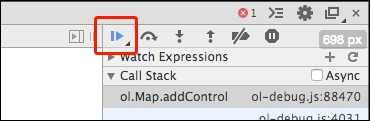

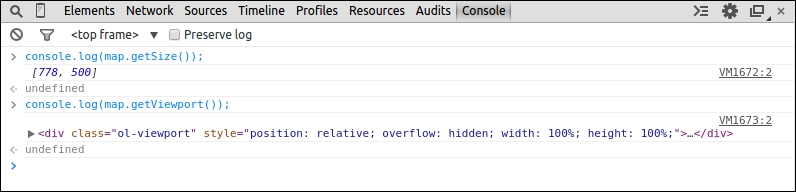

addControl method to add one control at a time, so we need a way of doing this for each individual controls in the collection. Collections have a forEach method that invokes a function for each item in the collection, which sounds ideal! Let's give it a try by running the following code in the Console tab:controls.forEach(map.addControl);

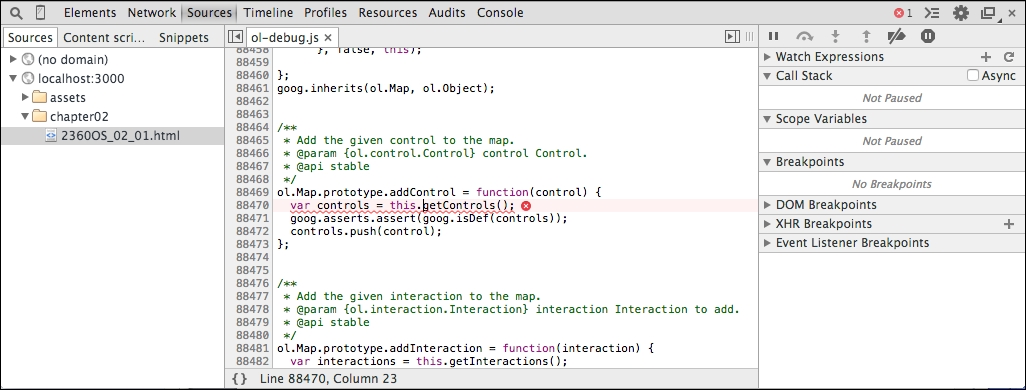

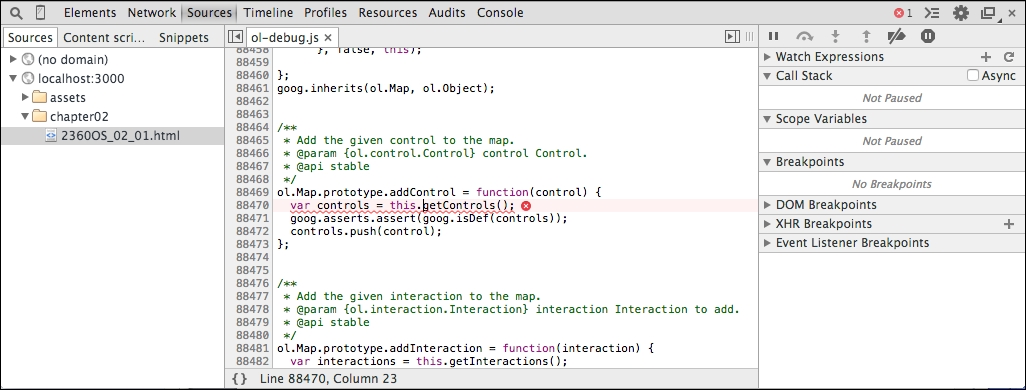

Something is not right, we are getting an error. Let's investigate.

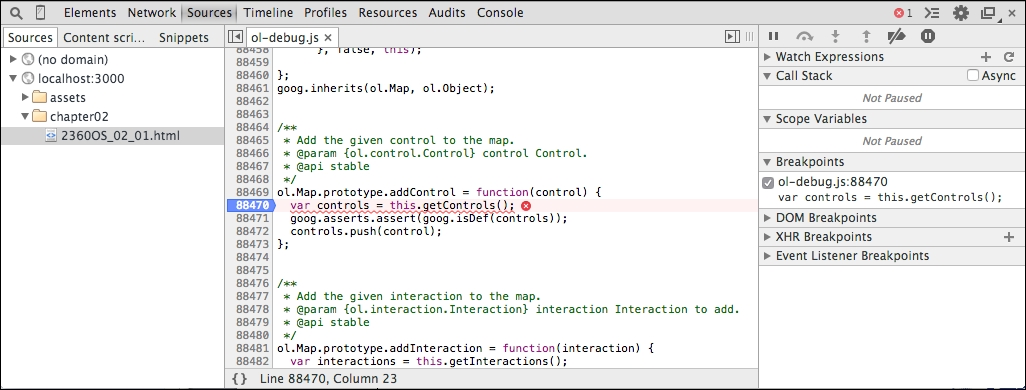

this.getControls(). Move the mouse over the this keyword and the debugger will show us what its value is. Now, we can see that this is the Window object and not a Map class object, which is why the getInteractions method is undefined! We need to provide the correct object, map, as the scope of the forEach function call by passing it as the second argument.

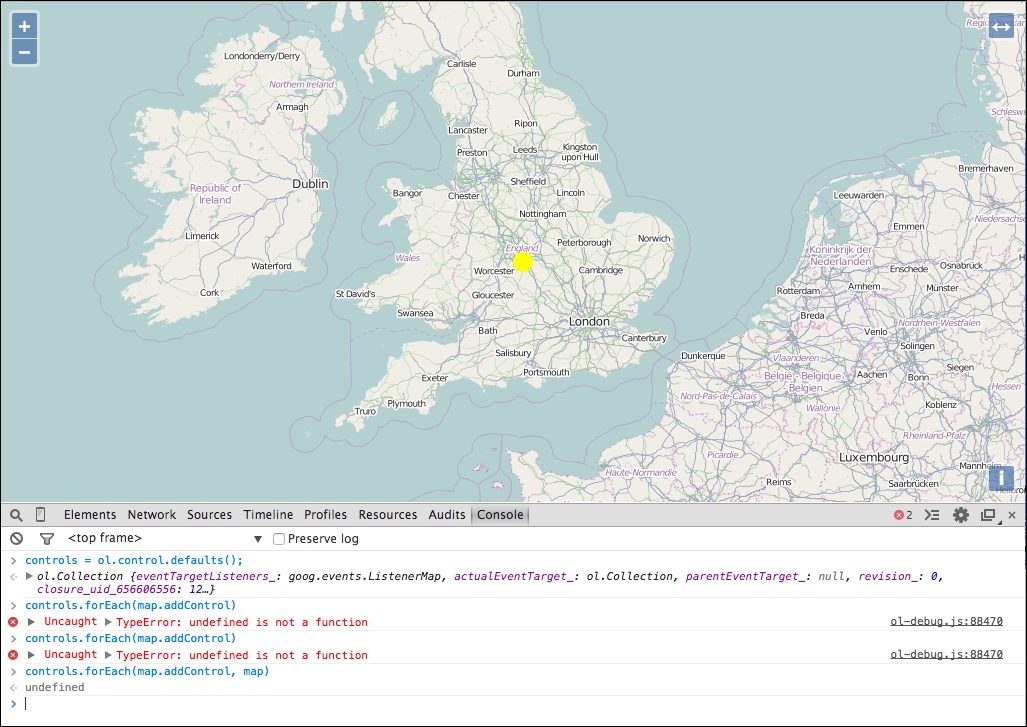

controls.forEach(map.addControl, map);

Much better! Now, we have all our controls back.

We used the Developer tools console to execute some JavaScript and modify our running application to add the default zoom controls that were missing. Along the way, we ran into a problem and switched to the debug build of the OpenLayers library so that we could get more useful information about problems we ran into. We touched briefly on using the powerful Developer tools, including the Console and Sources panels.

There are a great many things we can do with the Developer tools, and this just touches briefly on one aspect of them. Please read Appendix C, Squashing Bugs with Web Debuggers to learn more about using the Developer tools in application development.

In the following sections, we'll look a little more closely at each of the components we've introduced so far, starting with the view class.

Based on the previous example, use the Console to add the default interactions to the running application. You can get the default interactions by calling the ol.interaction.defaults() method.

The OpenLayers view class, ol.View, represents a simple two-dimensional view of the world. It is responsible for determining where, and to some degree how, the user is looking at the world. We'll cover views in more detail at the end of Chapter 3, Charting the Map Class, but briefly, it is responsible for managing the following information:

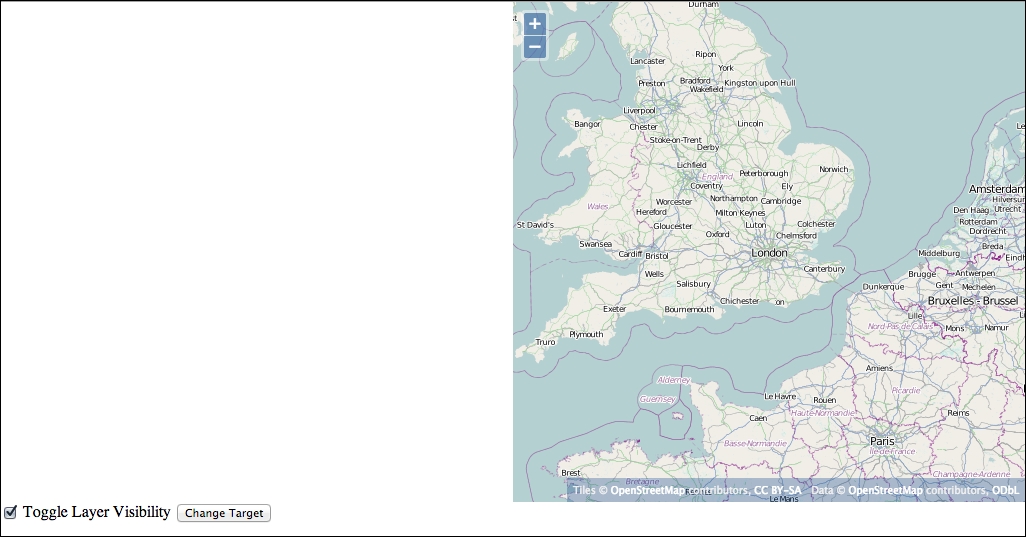

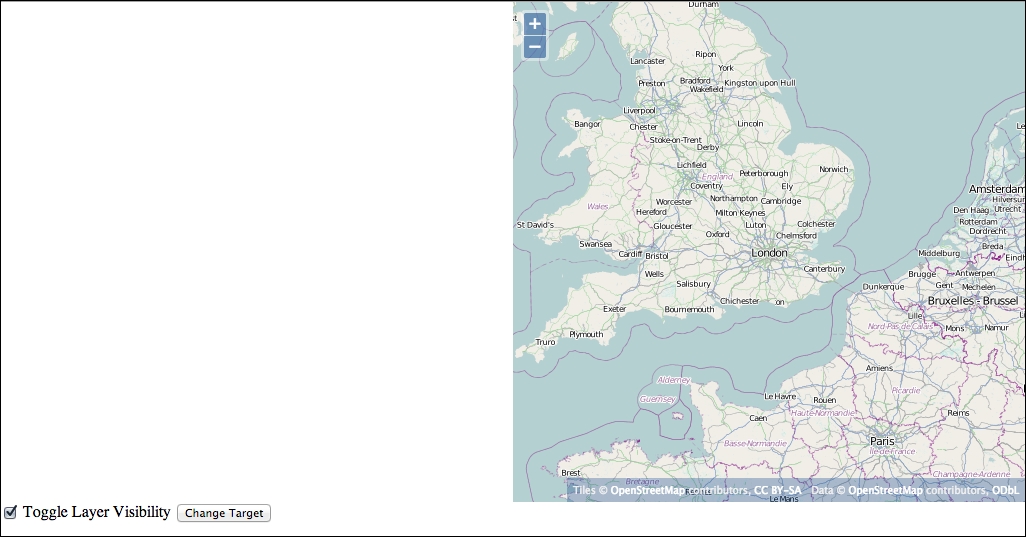

Although you can create a map without a view, it won't display anything until a view is assigned to it. Every map must have a view in order to display any map data at all. However, a view may be shared between multiple instances of the Map class. This effectively synchronizes the center, resolution, and rotation of each of the maps. In this way, you can create two or more maps in different HTML containers on a web page, even showing different information, and have them look at the same world position. Changing the position of any of the maps (for instance, by dragging one) automatically updates the other maps at the same time! We'll see an example of this in the next chapter.

So, if the view is responsible for managing where the user is looking in the world, which component is responsible for determining what the user sees there? That's the job of layers and overlays.

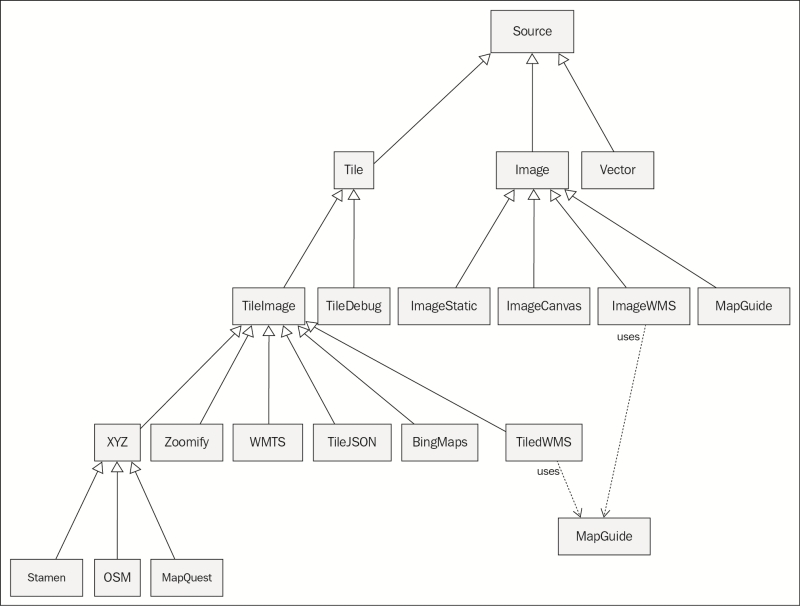

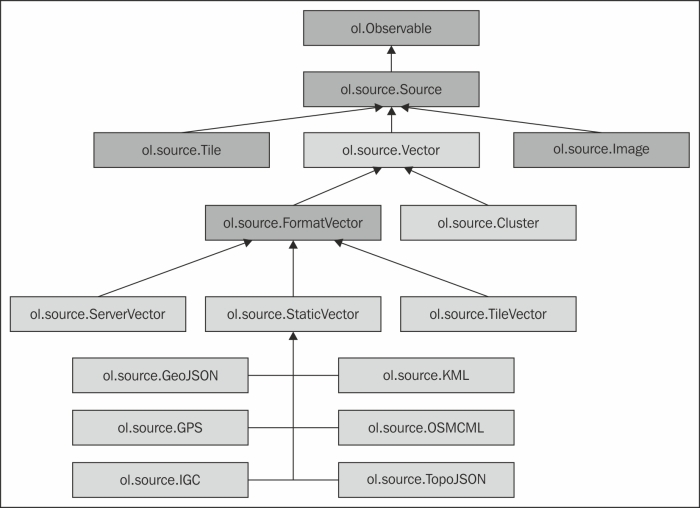

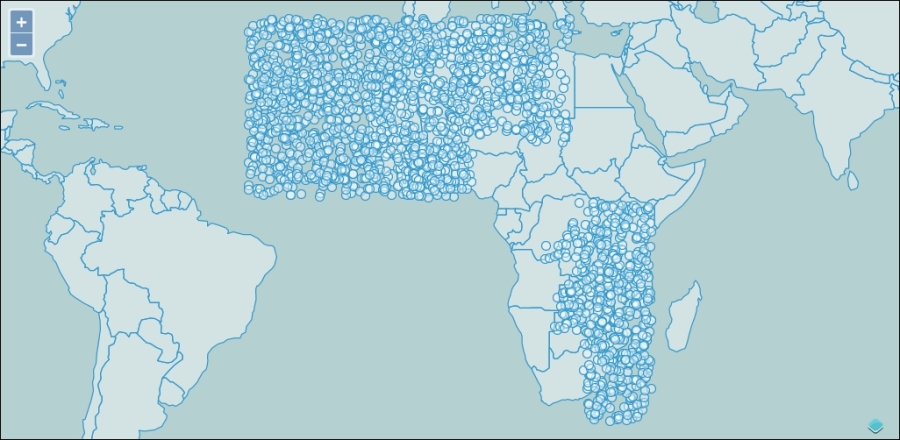

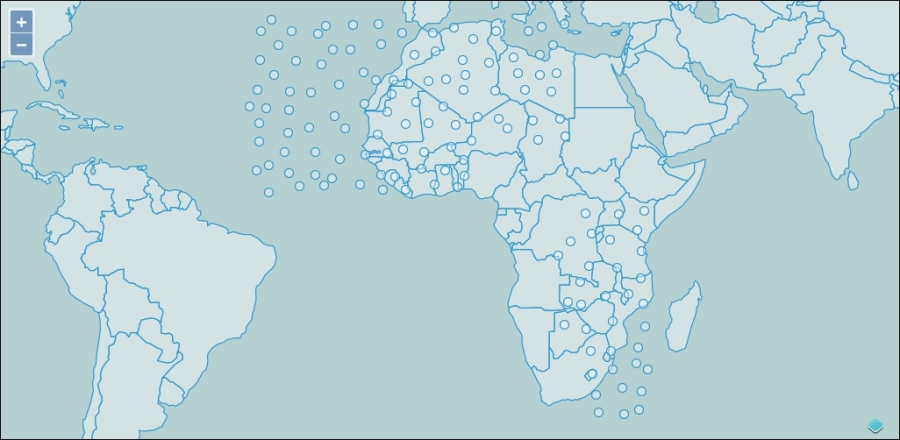

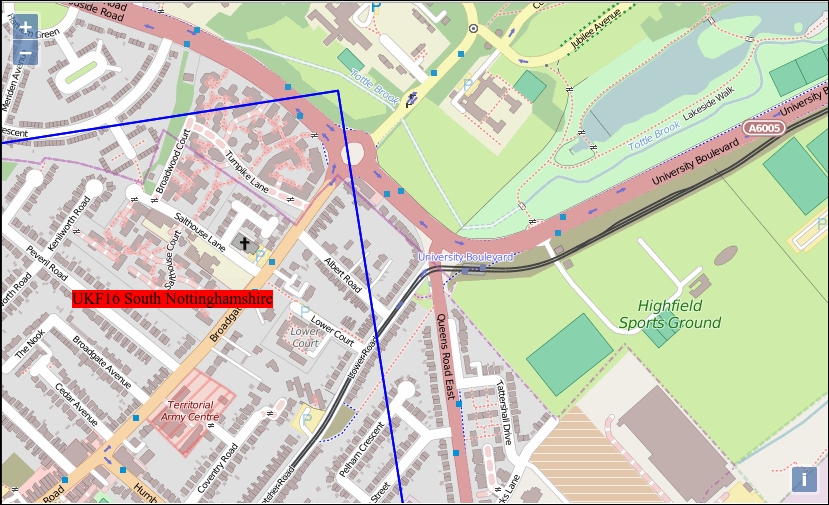

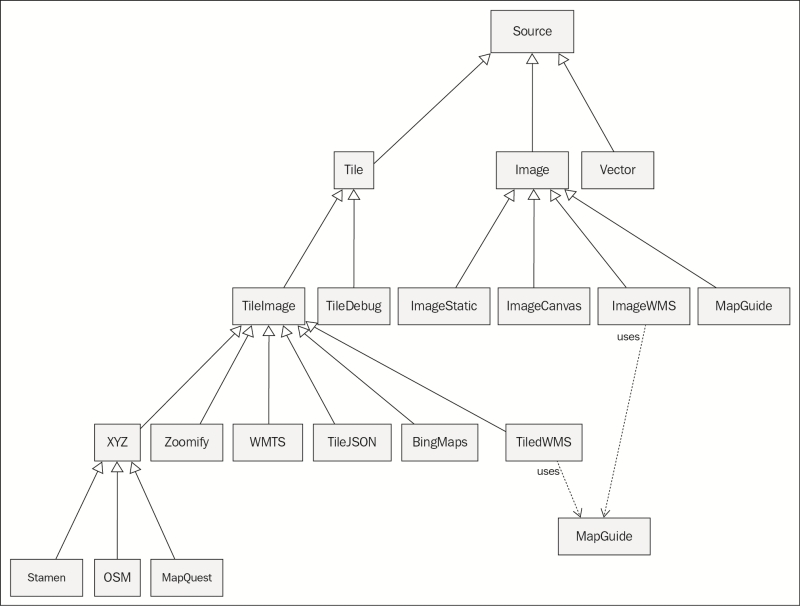

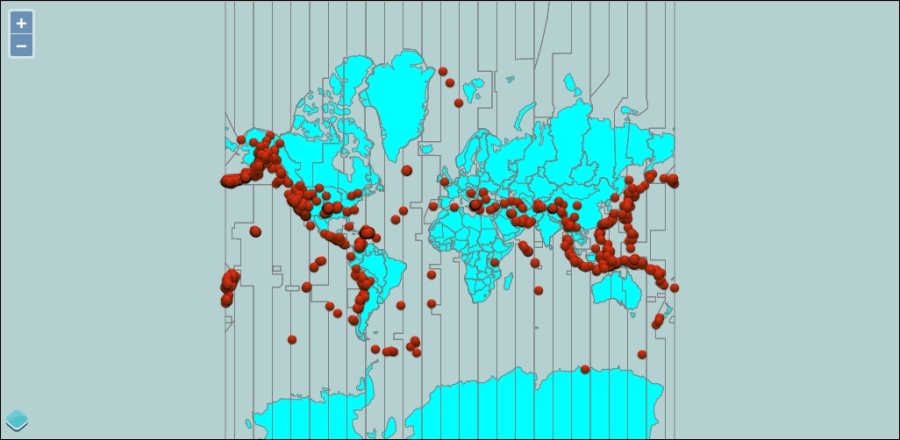

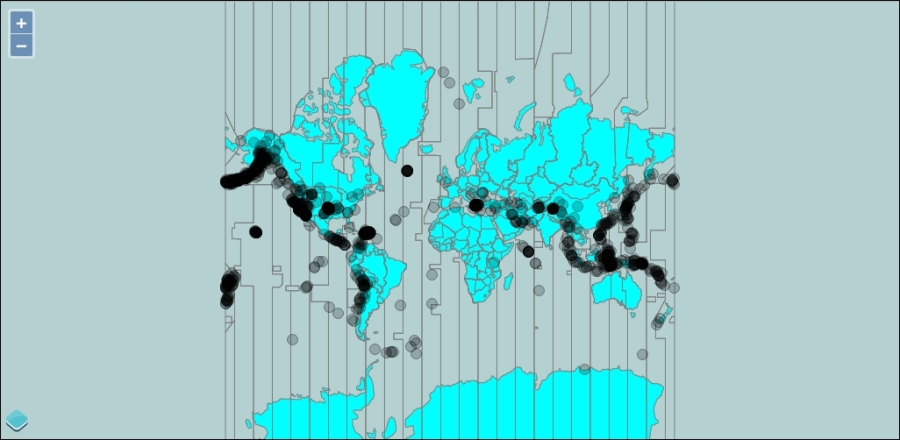

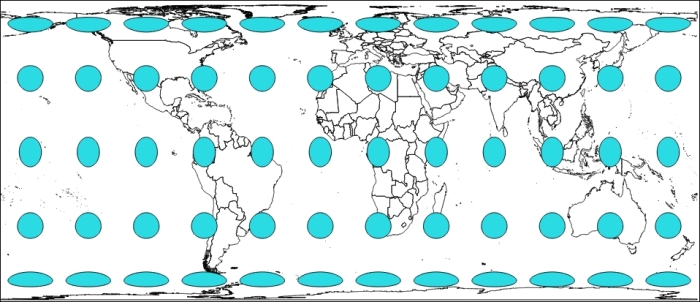

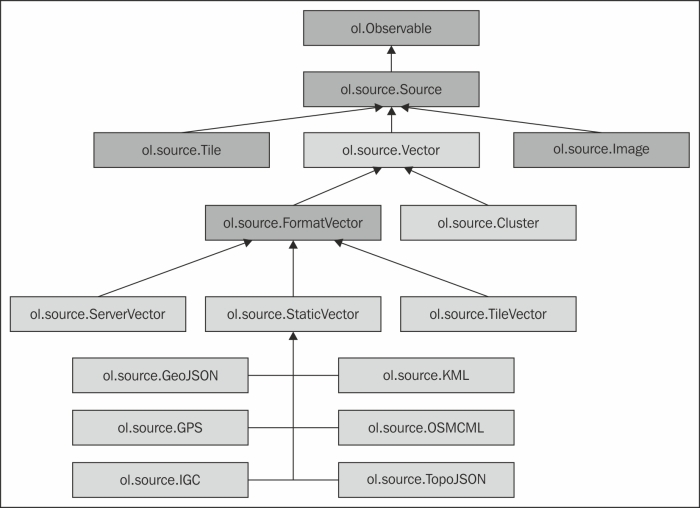

A layer provides access to a source of geospatial data. There are two basic kinds of layers, that is, raster and vector layers:

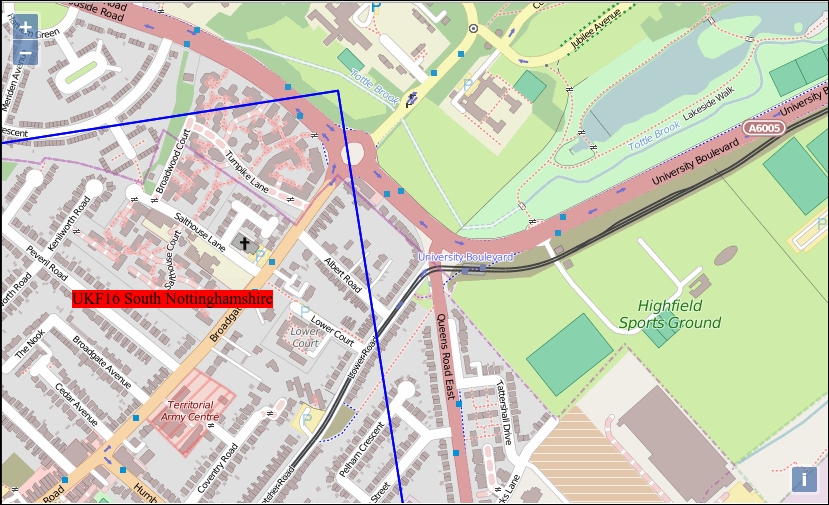

Layers are not the only way to display spatial information on the map. The other way is to use an overlay. As we saw in the example earlier in this chapter, we can create instances of ol.Overlay and add them to the map at specific locations. The overlay then positions its content (an HTML element) on the map at the specified location. The HTML element can then be used like any other HTML element.

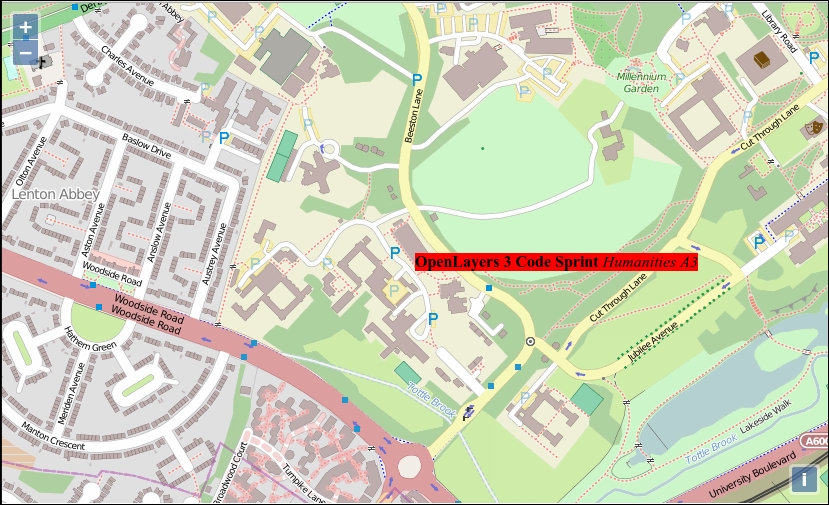

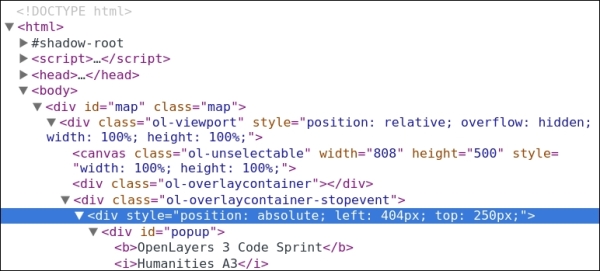

The most common use of overlays is to display spatially relevant information in a pop-up dialog in response to the mouse moving over, or clicking on a geographic feature.

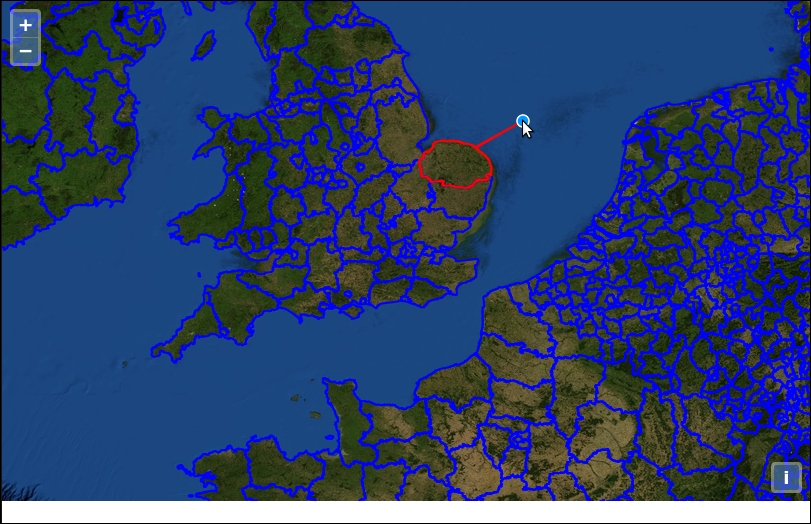

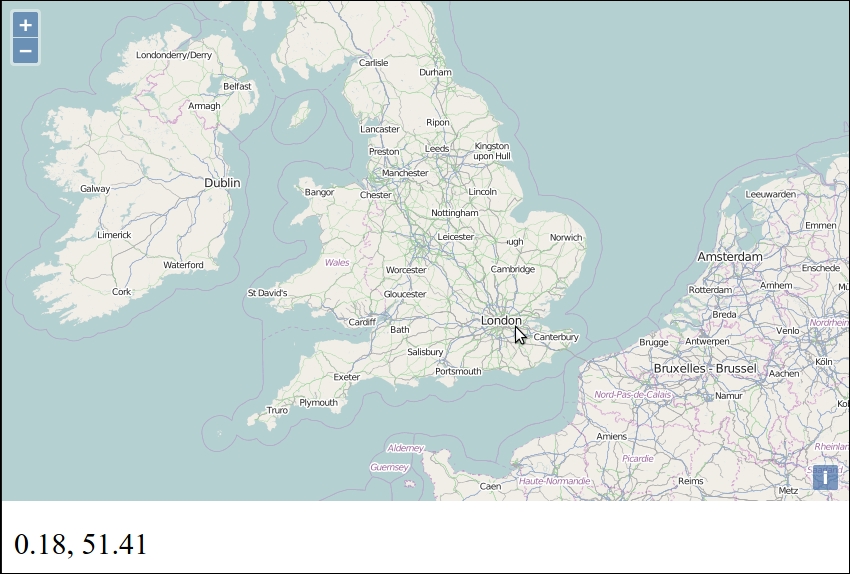

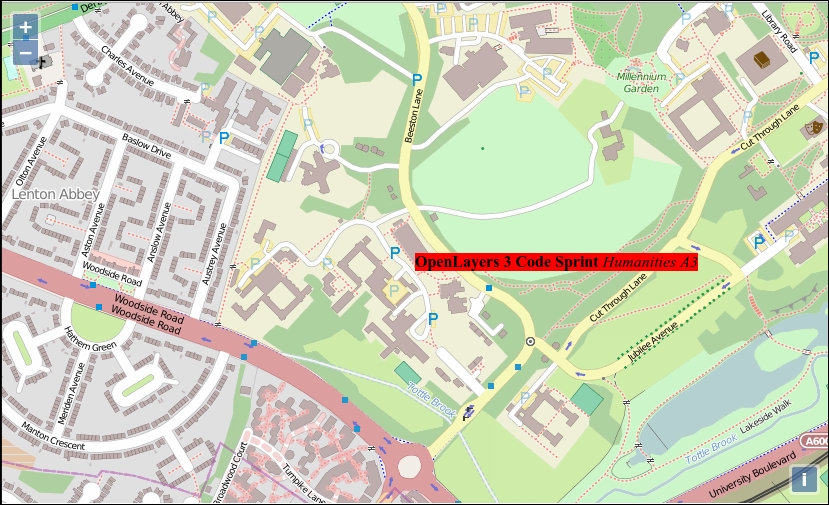

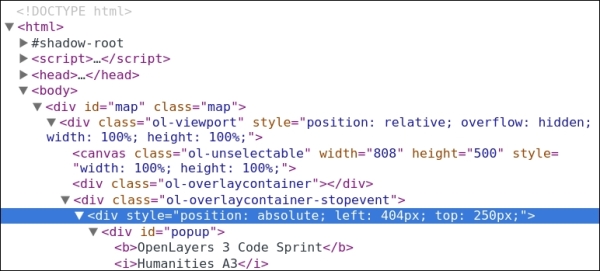

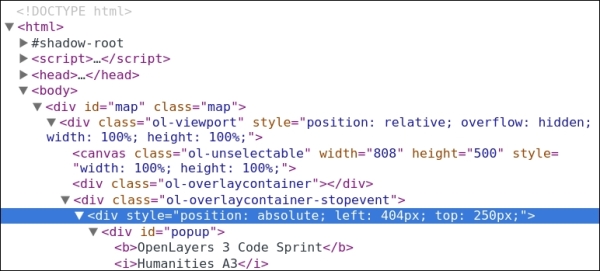

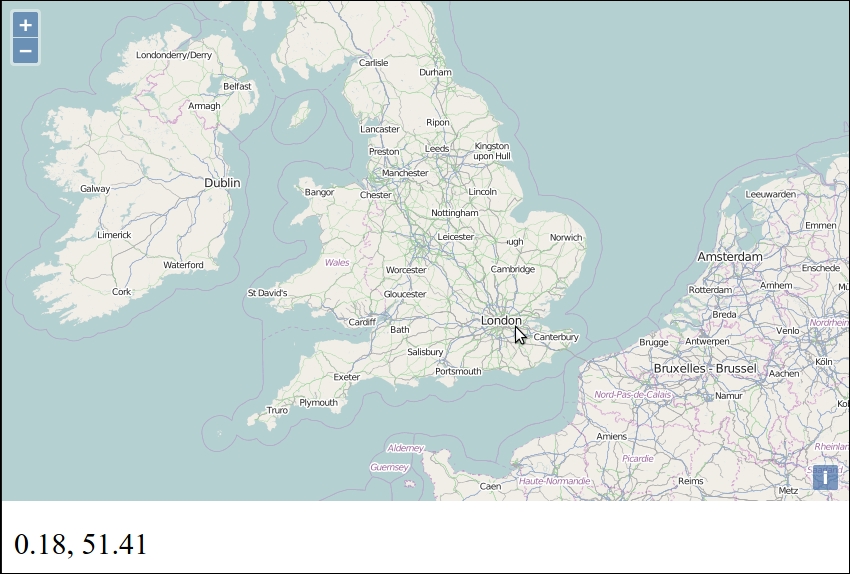

In the previous example, we added an overlay but we didn't really investigate how it behaves. Let's do something a bit more interesting with overlays to illustrate what they do. In this example, we'll build an OpenLayers application that displays the latitude and longitude of the mouse position in an overlay when you click on the map:

overlay.html in the sandbox directory. Add the standard boilerplate content to get started:<!doctype html>

<html>

<head>

<title>OpenLayers Overlays</title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="../assets/ol3/css/ol.css" type="text/css" />

<link rel="stylesheet" href="../assets/css/samples.css" type="text/css" />

</head>

<body>

<div id="map" class="map"></div>

<script src="../assets/ol3/js/ol.js"></script>

<script>

</script>

</body>

</html>var layer = new ol.layer.Tile({

source: new ol.source.OSM()

});

var center = ol.proj.transform([-1.812, 52.443], 'EPSG:4326', 'EPSG:3857');

var view = new ol.View({

center: center,

zoom: 6

});

var map = new ol.Map({

target: 'map',

layers: [layer],

view: view

});<div> element. You can change the style of the element if you wish:<div id="overlay" style="background-color: white; border-radius: 10px; border: 1px solid black; padding: 5px 10px;">

Map class:var overlay = new ol.Overlay({

element: document.getElementById('overlay'),

positioning: 'bottom-center'

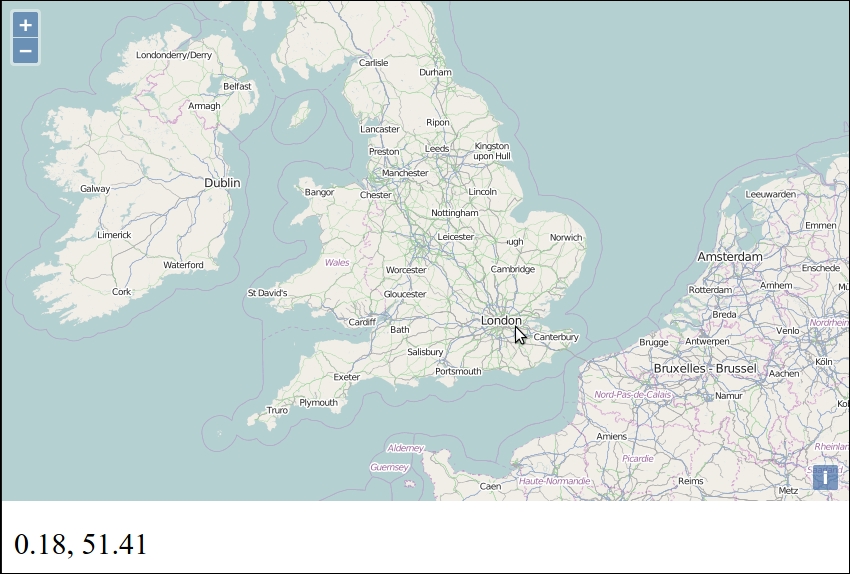

});map.on('click', function(event) {

var coord = event.coordinate;

var degrees = ol.proj.transform(coord, 'EPSG:3857', 'EPSG:4326')

var hdms = ol.coordinate.toStringHDMS(degrees);

var element = overlay.getElement();

element.innerHTML = hdms;

overlay.setPosition(coord);

map.addOverlay(overlay);

});

In this example, we illustrated how an overlay is positioned at a geographic location on the map, how it moves with the map to stay at that same location, and how it can be used to display information about some location.

After setting up the boilerplate HTML structure for the page, we added a raster layer with the OpenStreetMap data, a view, and a map to the application. We then created an overlay object pointing at an HTML element for content and with the positioning set to 'bottom-center', which tells OpenLayers to align the bottom, center of the HTML element with the geographic position of the overlay. This means that the overlay will appear above the location, centered on it.

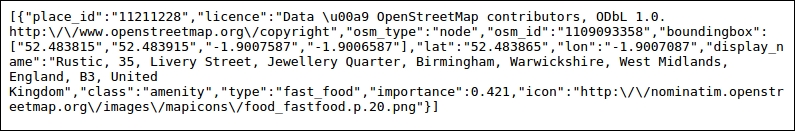

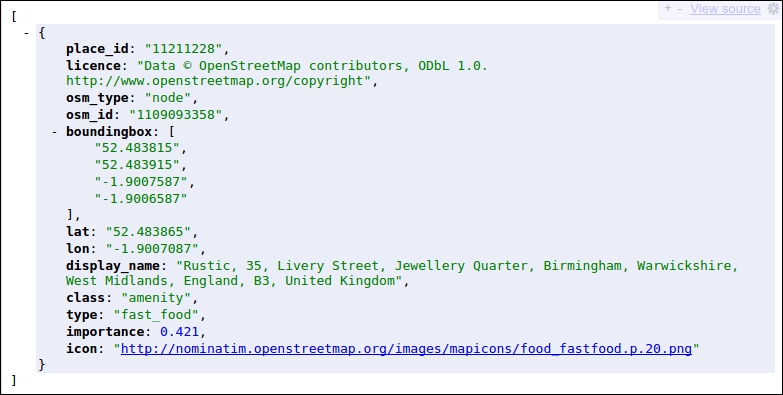

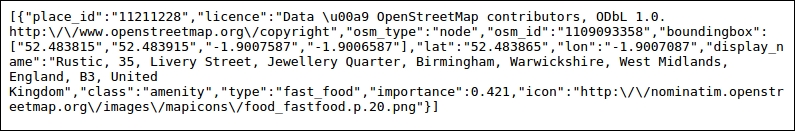

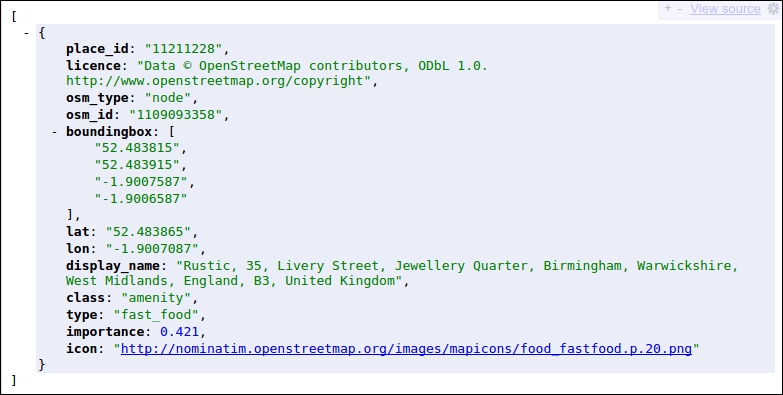

The last step was to register an event handler (more on events later in this chapter) for the map's click event. When the user clicks on the map, the event handler function is called with an event object that contains coordinate (the geographic position) of the click on the map. We transform the coordinate from the map's projection into decimal degrees (longitude and latitude values) and use a helper function in the OpenLayers library to format this into degrees minutes and seconds (a standard way of representing geographic location in human readable form). We then update the content of our overlay's HTML element with this information, set the position of the overlay to the coordinate provided with the event, and add it to the map using the addOverlay method.

If some of this seems overwhelming, don't worry, we'll be covering all of this in later chapters.

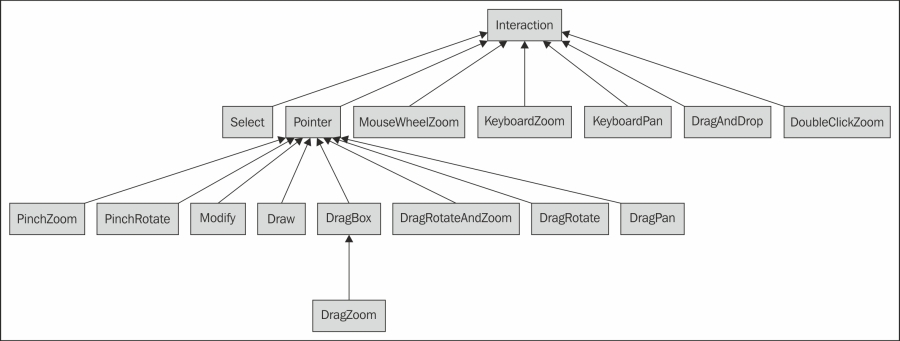

As mentioned earlier, the two components that allow users to interact with the map are interactions and controls. Let's look at them in a bit more detail.

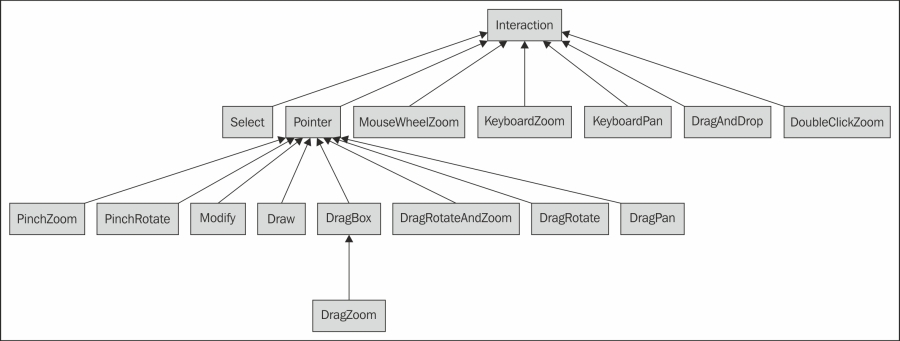

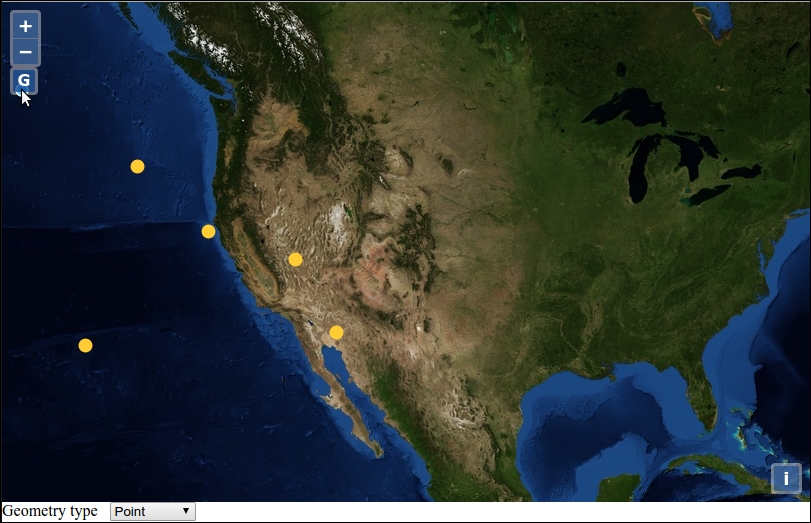

Interactions are components that allow the user to interact with the map via some direct input, usually by using the mouse (or a finger with a touch screen). Interactions have no visible user interface. The default set of interactions are:

ol.interaction.DoubleClickZoom: If you double-click the left mouse button, the map will zoom in by a factor of 2ol.interaction.DragPan: If you drag the map, it will pan as you move the mouseol.interaction.PinchRotate: On touch-enabled devices, placing two fingers on the device and rotating them in a circular motion will rotate the mapol.interaction.PinchZoom: On touch-enabled devices, placing two fingers on the device and pinching them together or spreading them apart will zoom the map out and in respectivelyol.interaction.KeyboardPan: You can use the arrow keys to pan the map in the direction of the arrowsol.interaction.KeyboardZoom: You can use the + and – keys to zoom in and outol.interaction.MouseWheelZoom: You can use the scroll wheel on a mouse to zoom the map in and outol.interaction.DragZoom: If you hold the Shift key while dragging on map, a rectangular region will be drawn and when you release the mouse button, you will zoom into that area.We will discuss interactions in detail in Chapter 8, Interacting with Your Map.

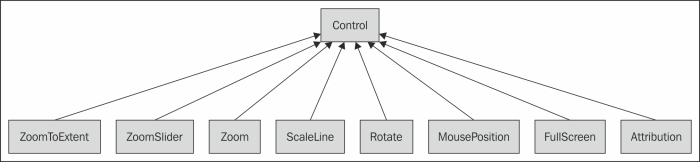

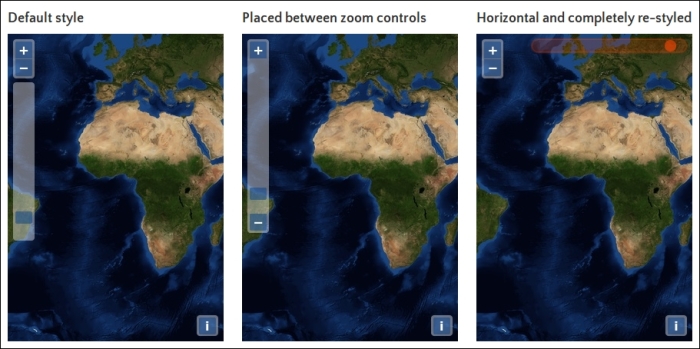

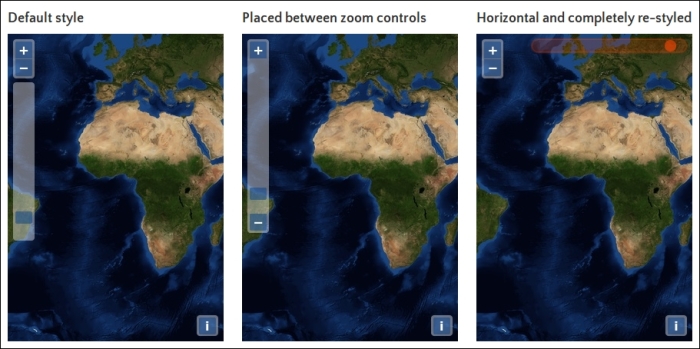

Controls are components that allow the user to modify the map state via some visible user interface element, such as a button. In the examples we've seen so far, we've seen zoom buttons in the top-left corner of the map and an attribution control in the bottom-right corner of the map. In fact, the default controls are:

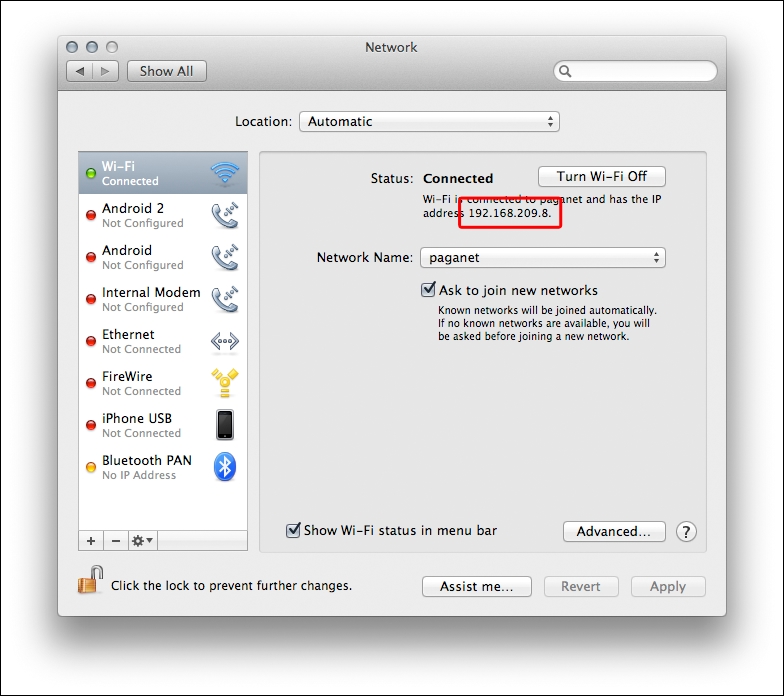

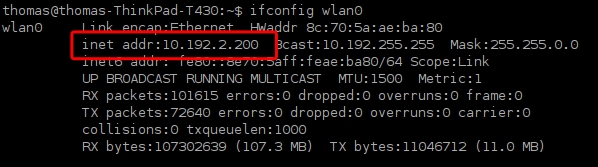

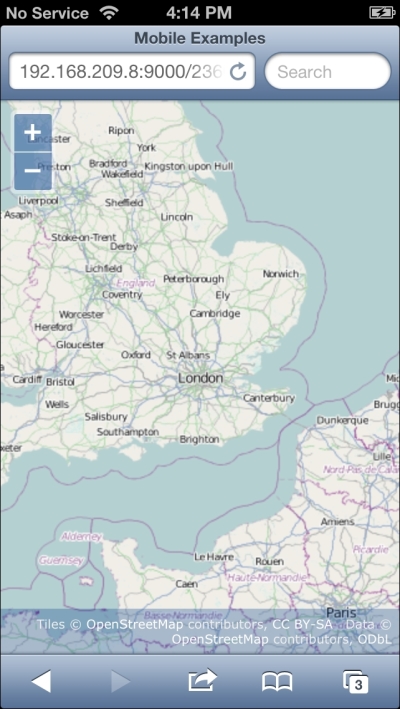

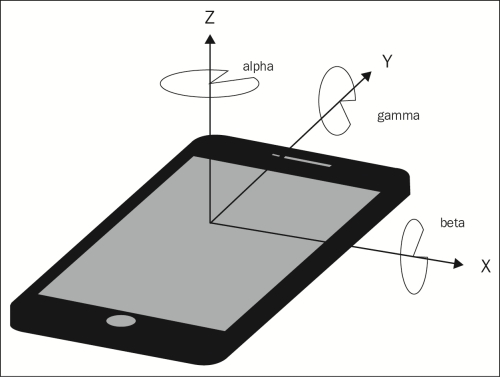

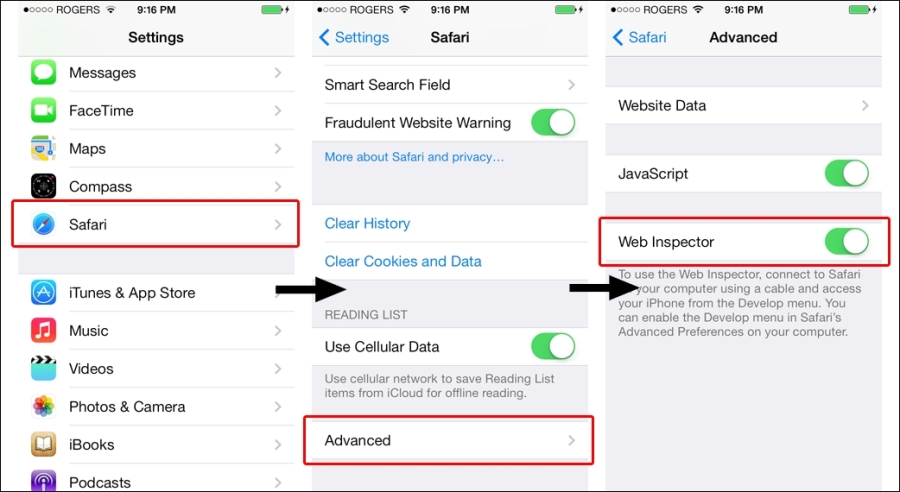

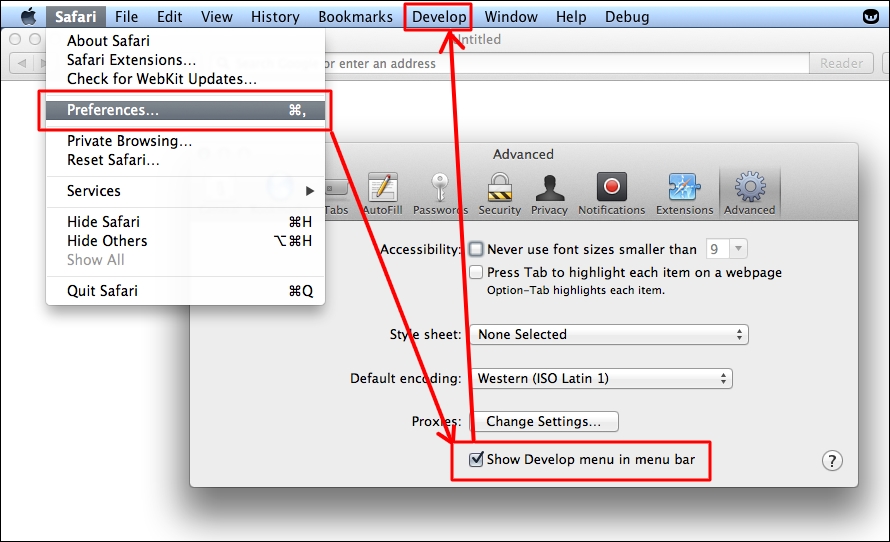

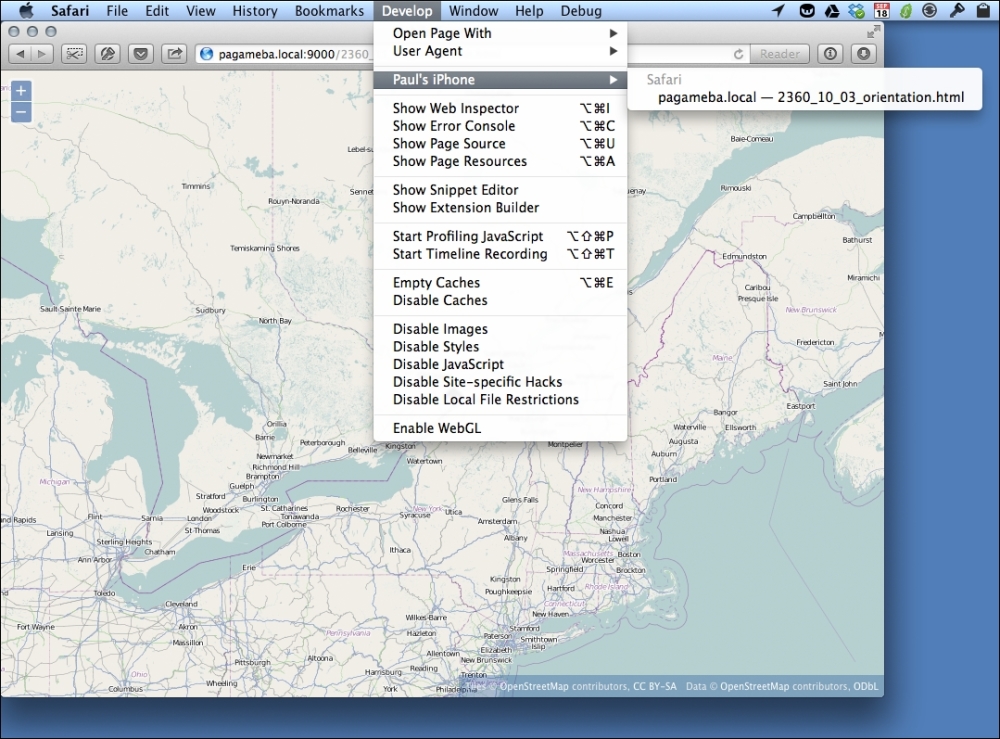

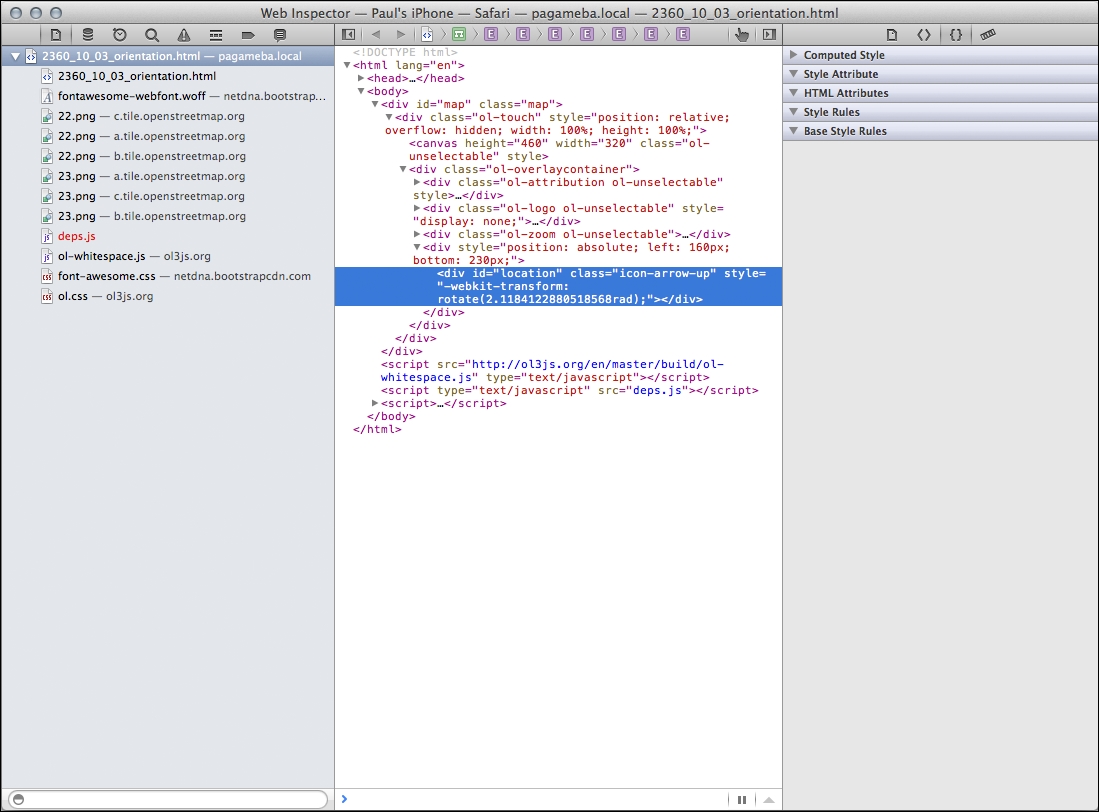

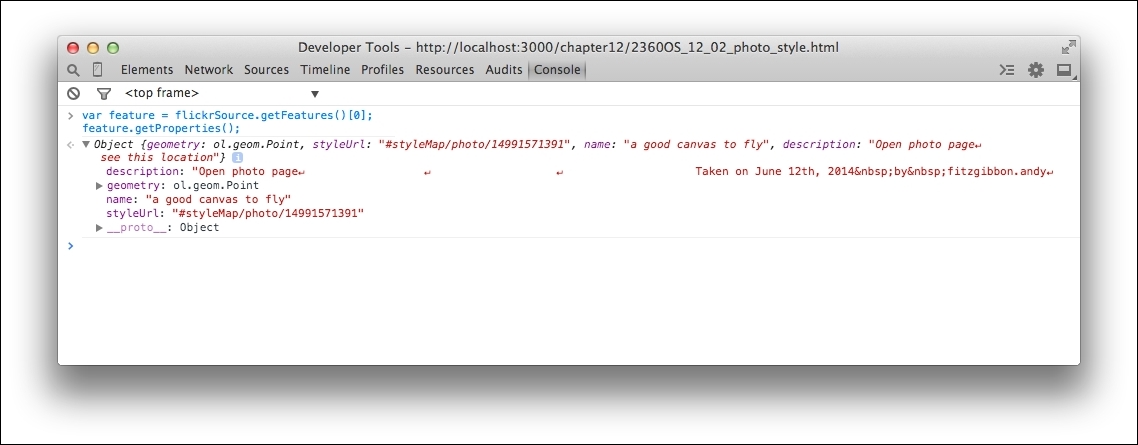

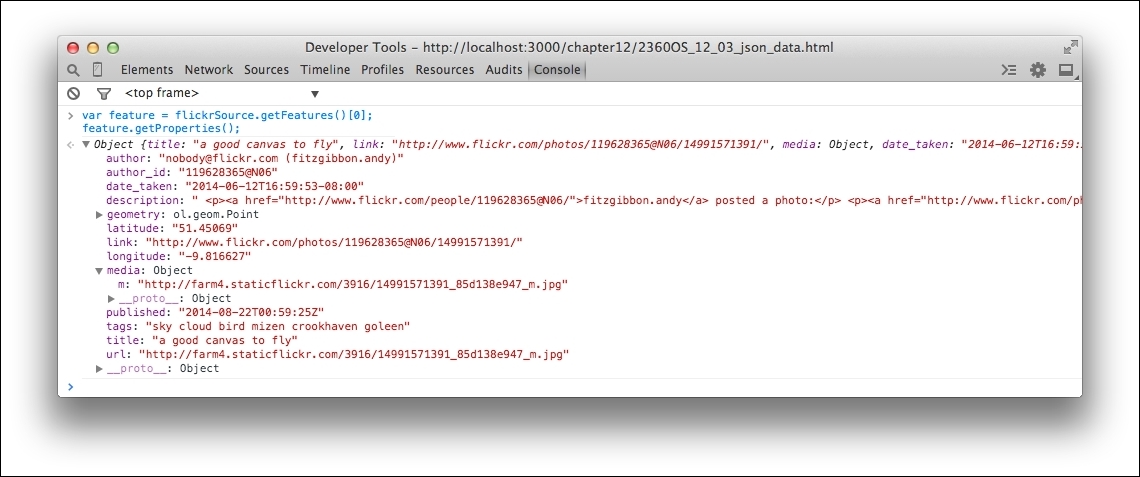

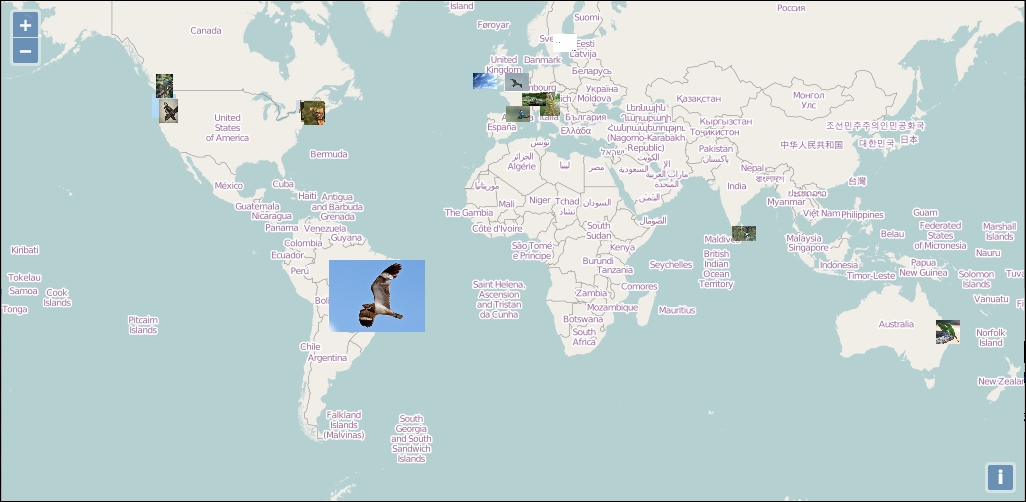

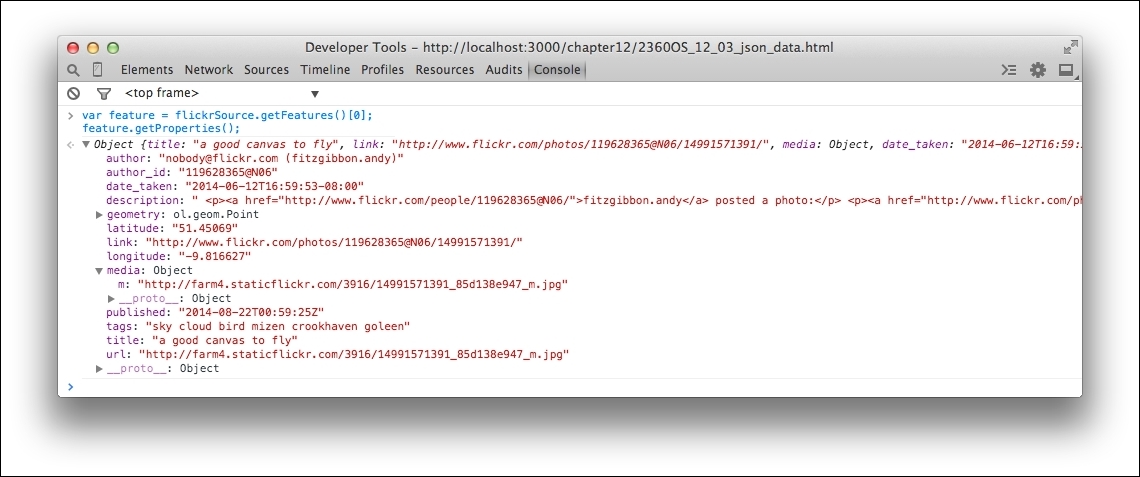

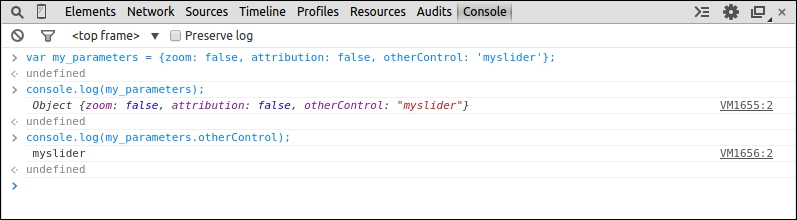

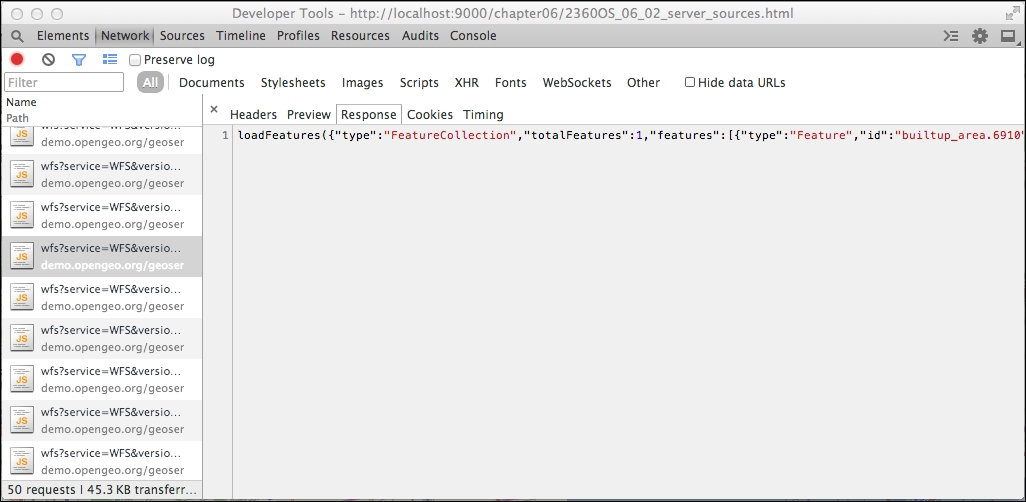

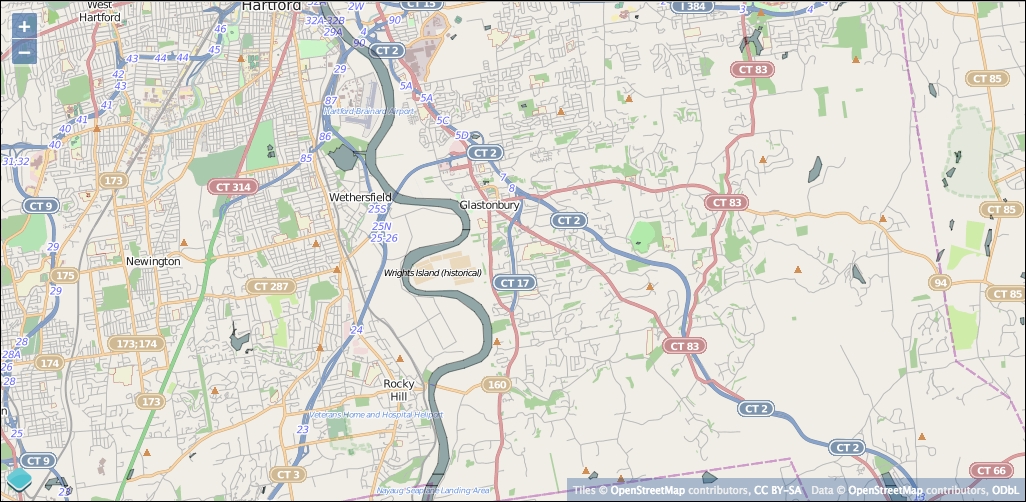

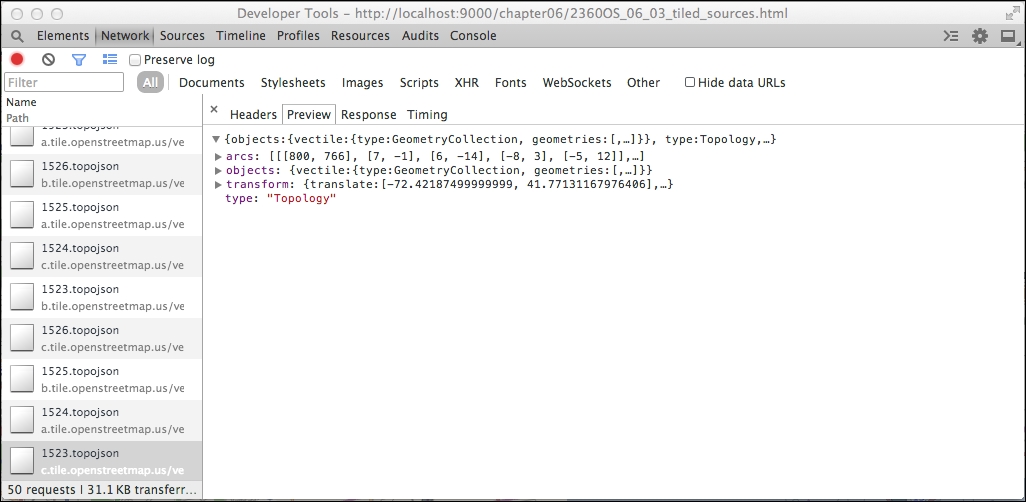

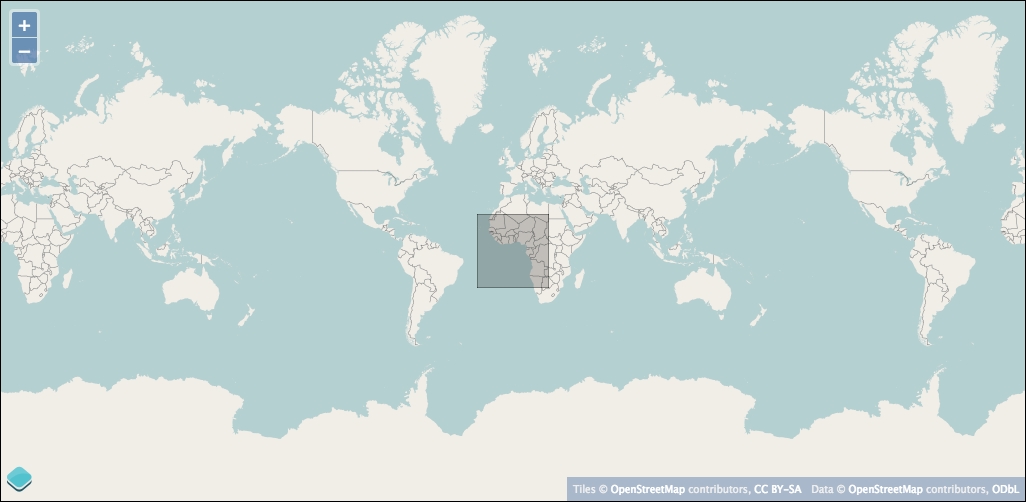

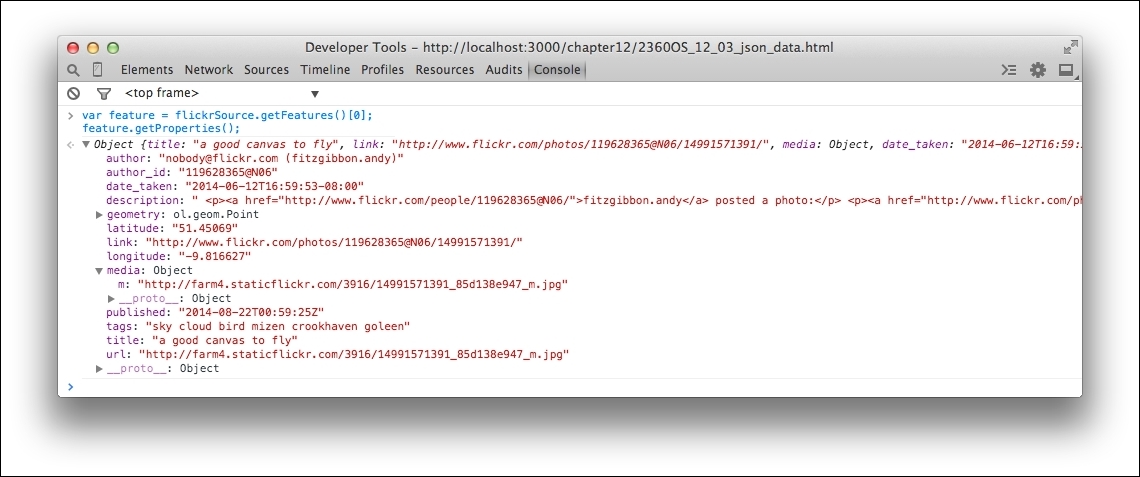

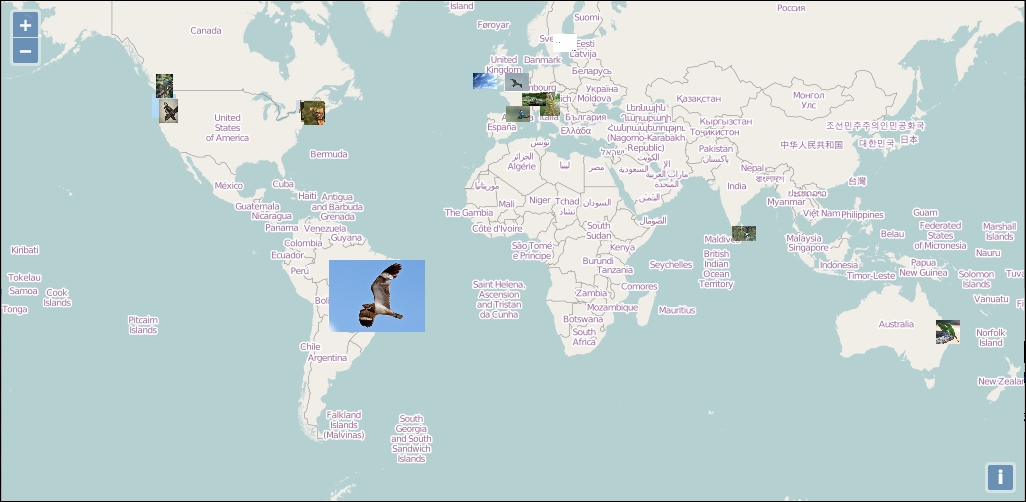

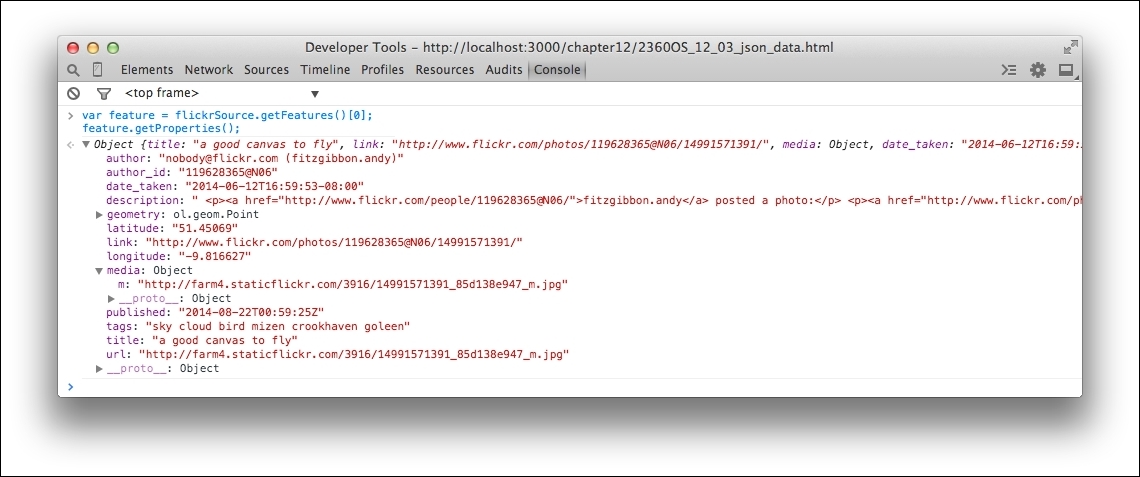

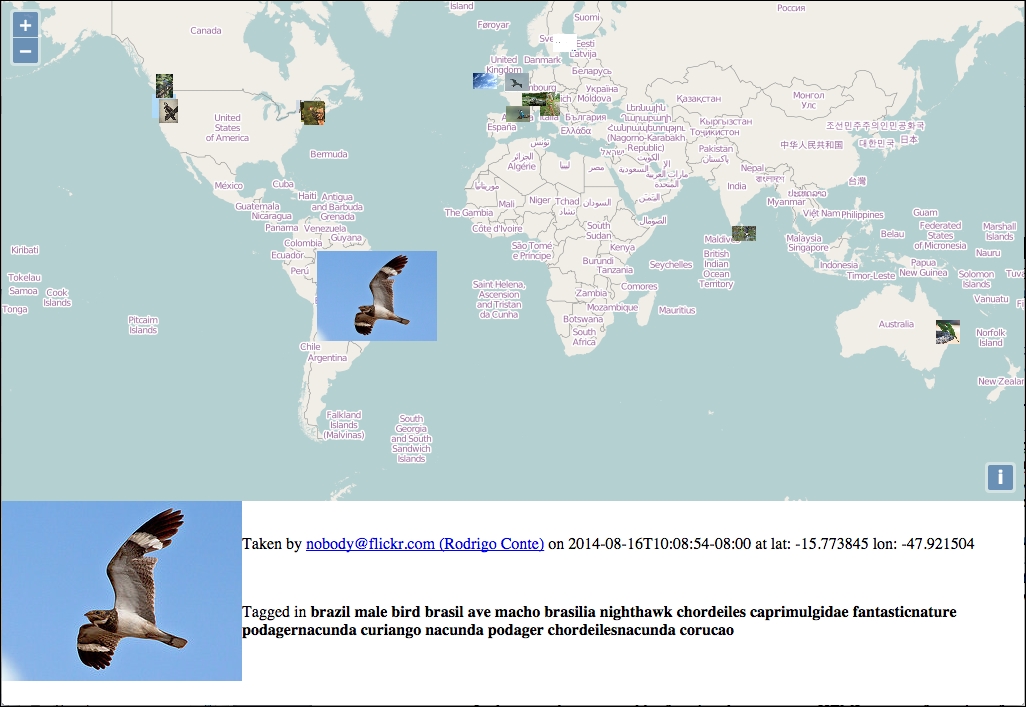

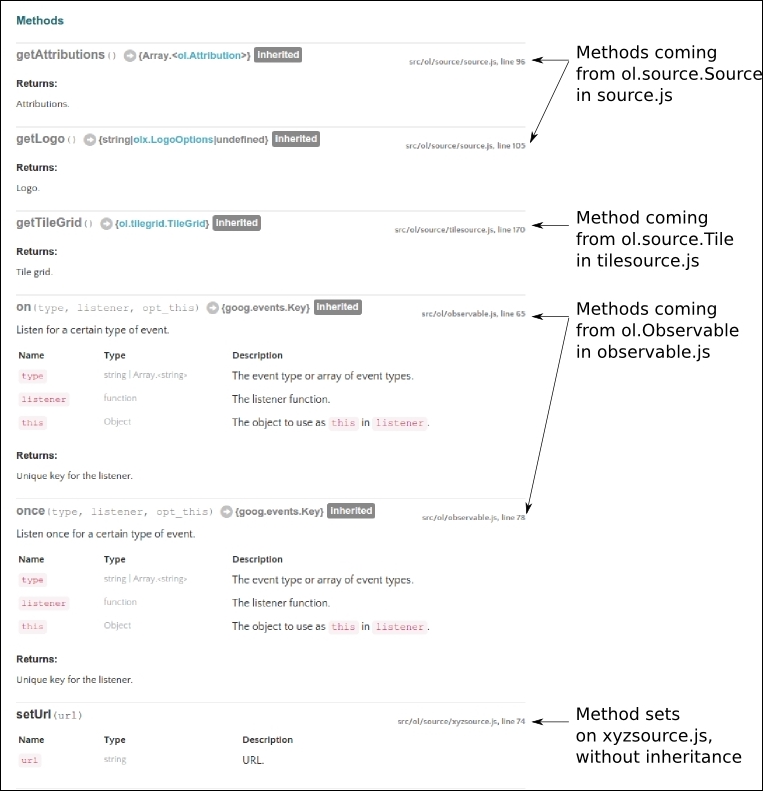

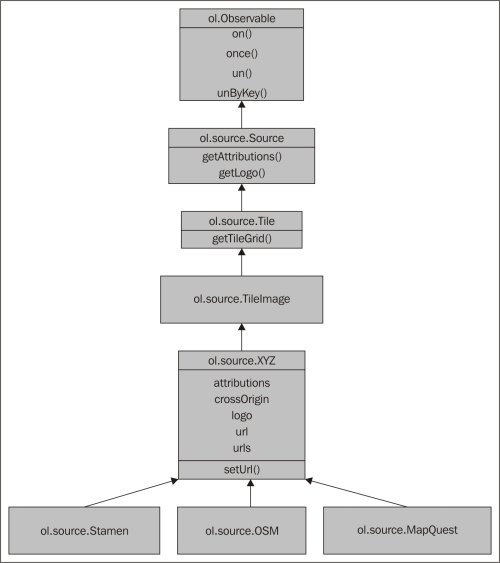

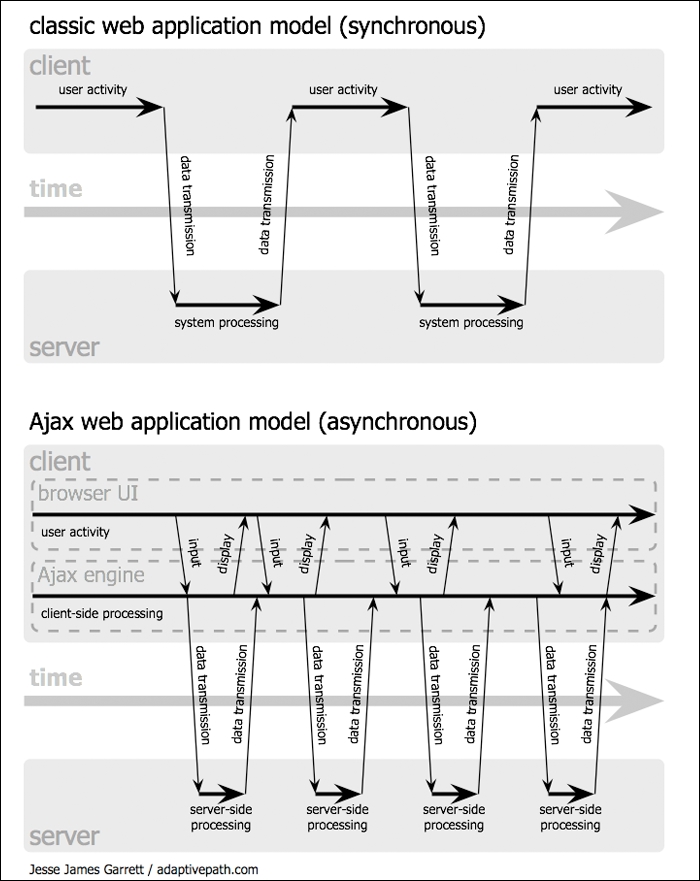

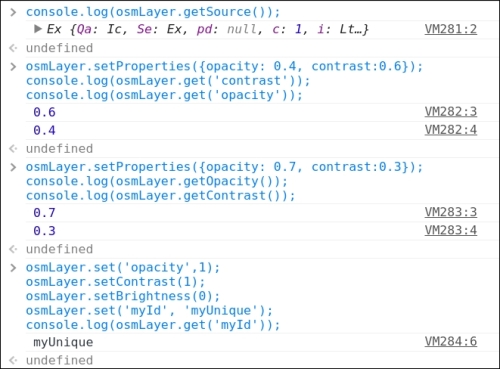

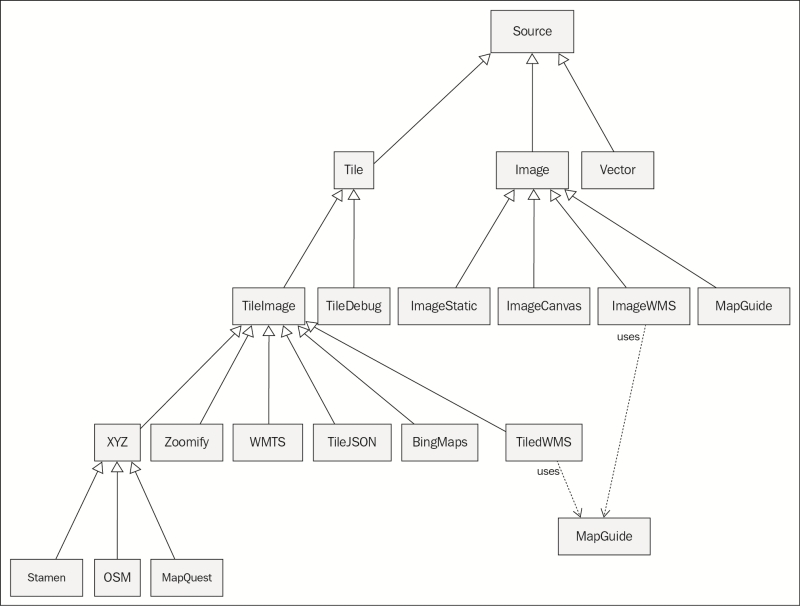

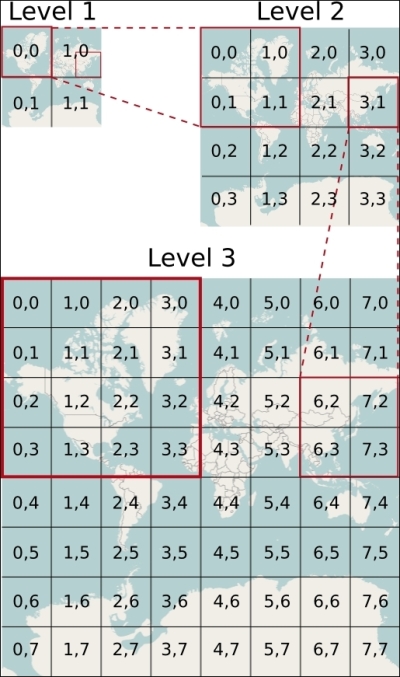

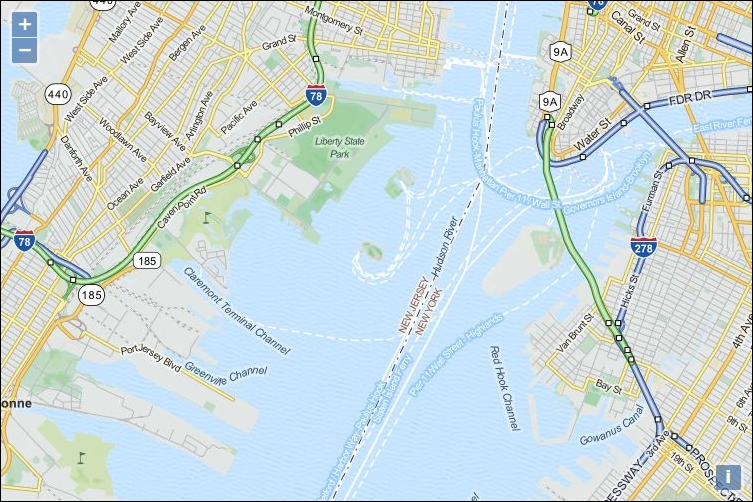

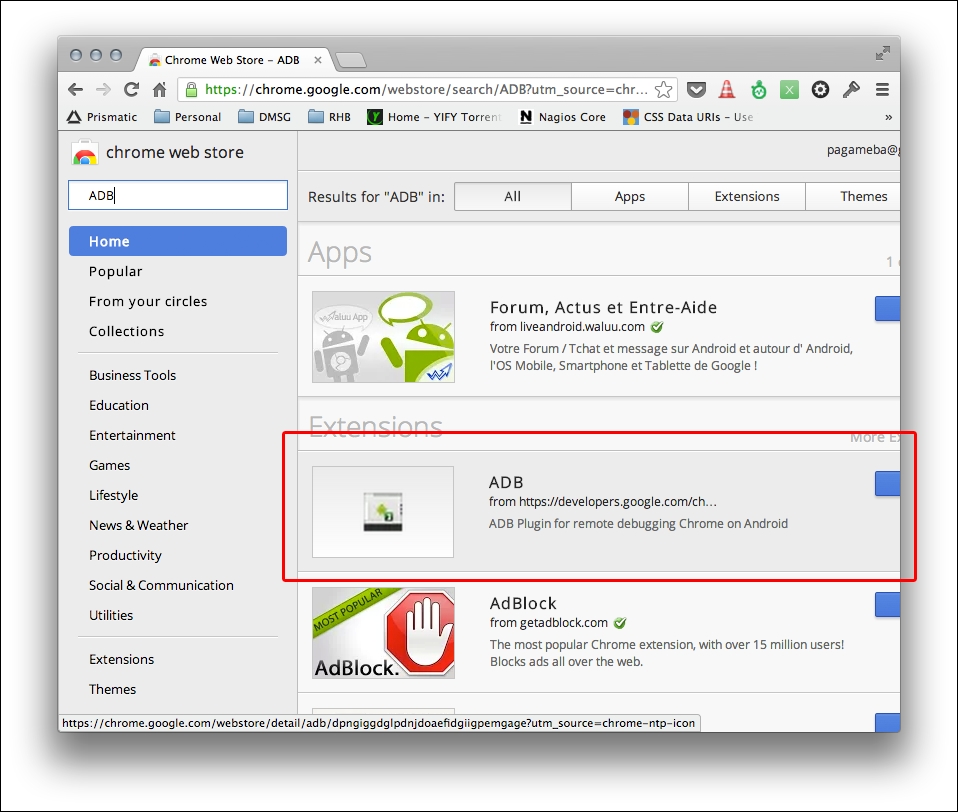

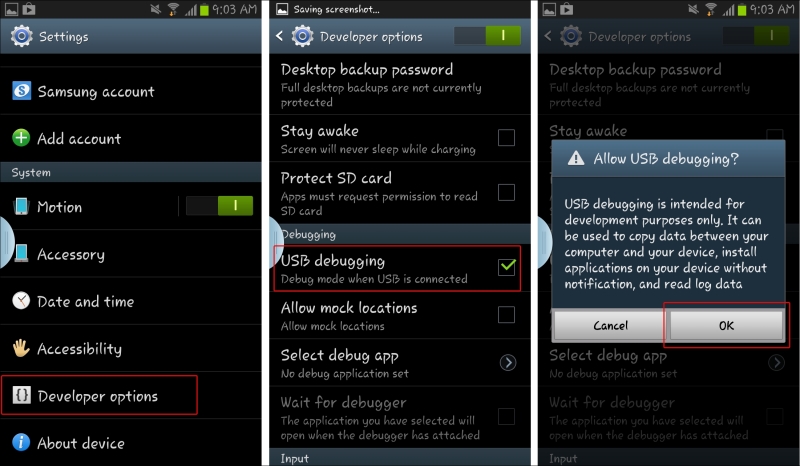

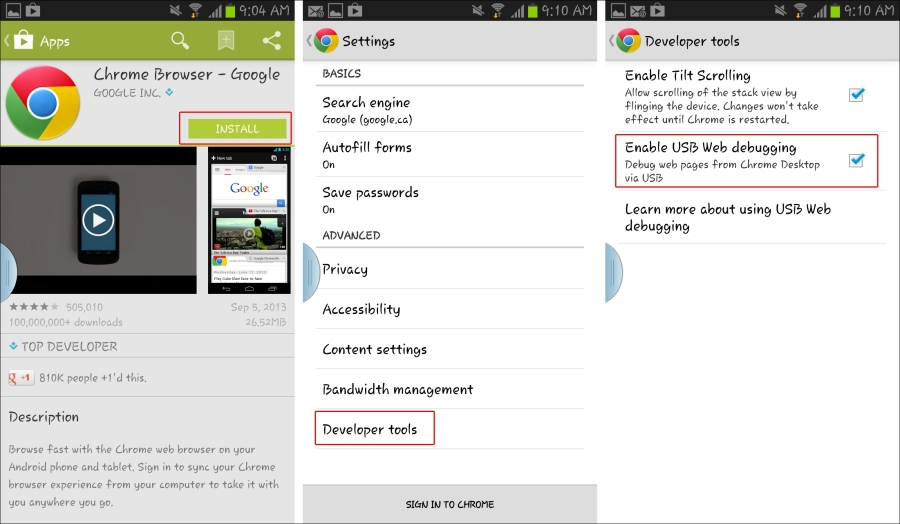

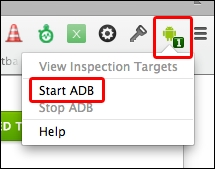

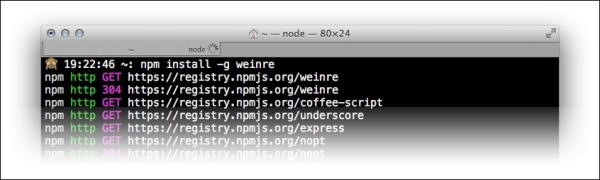

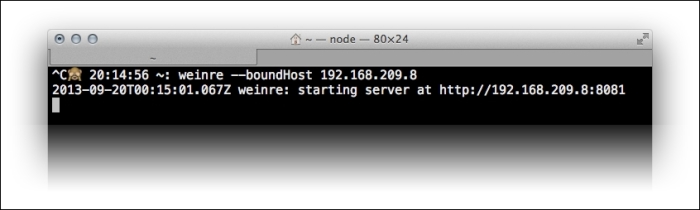

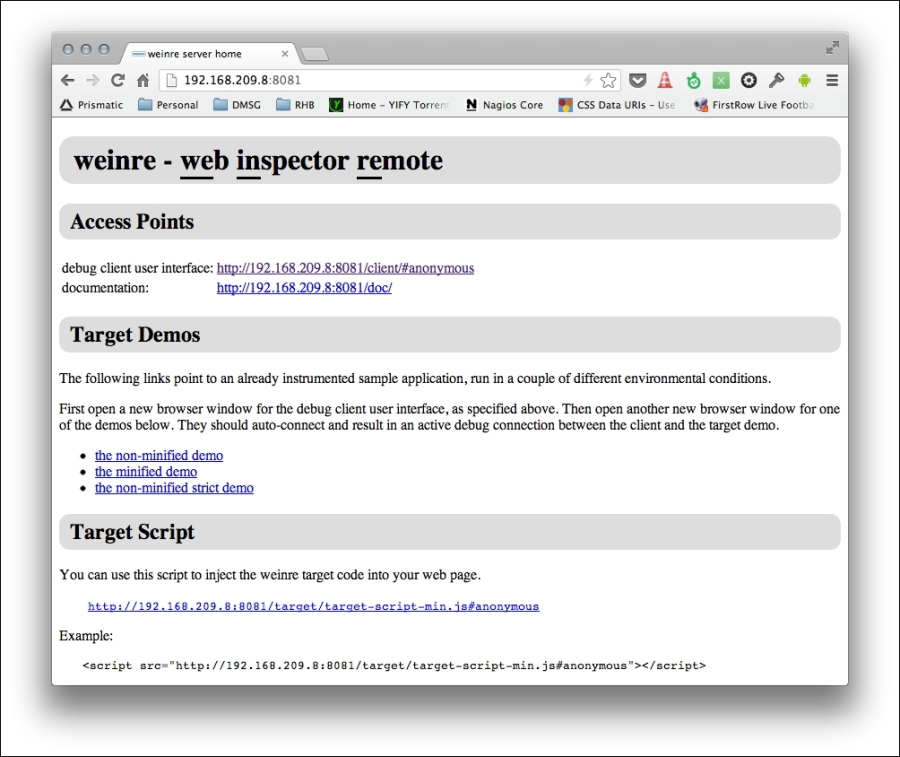

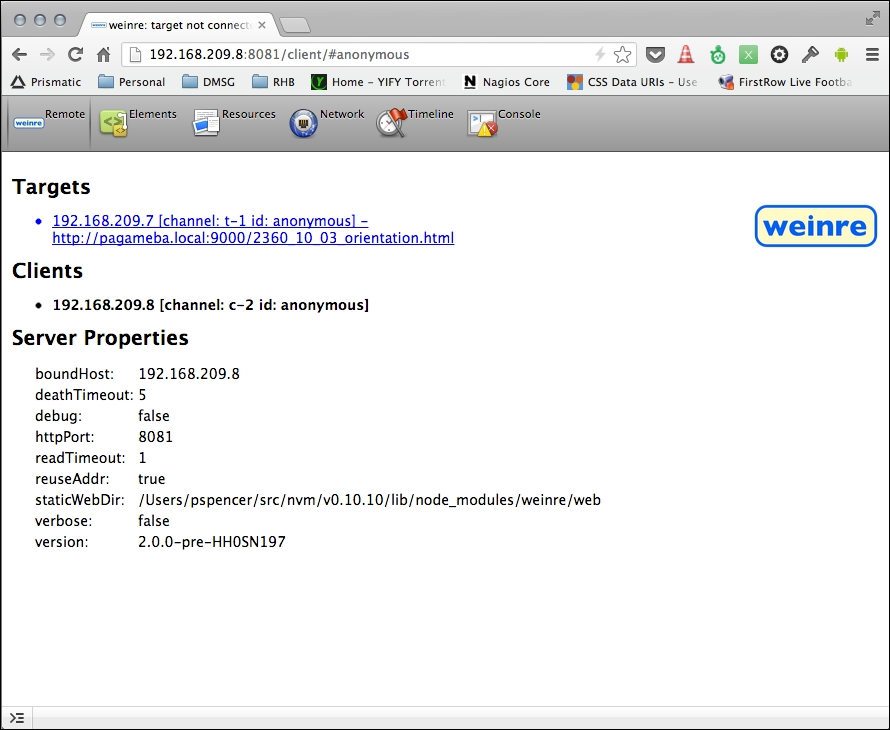

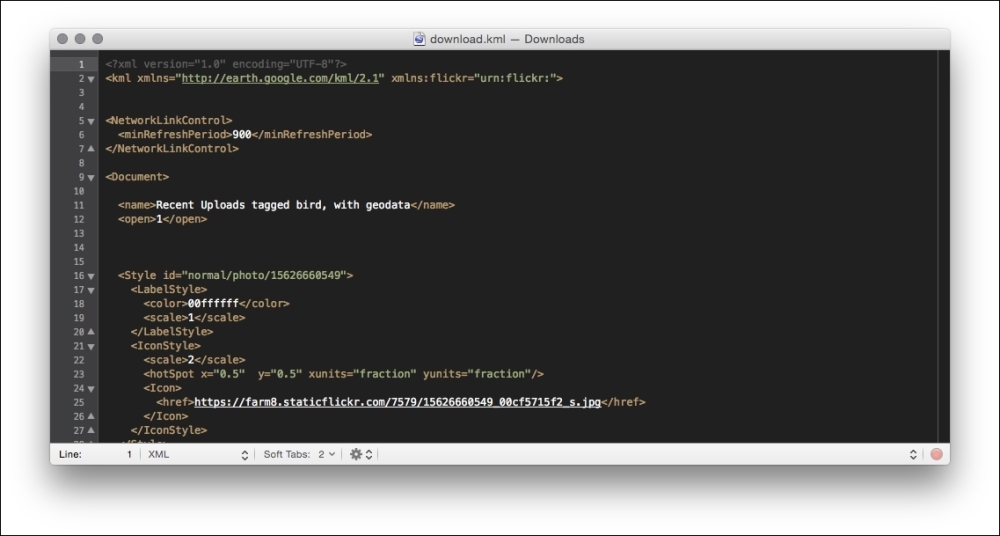

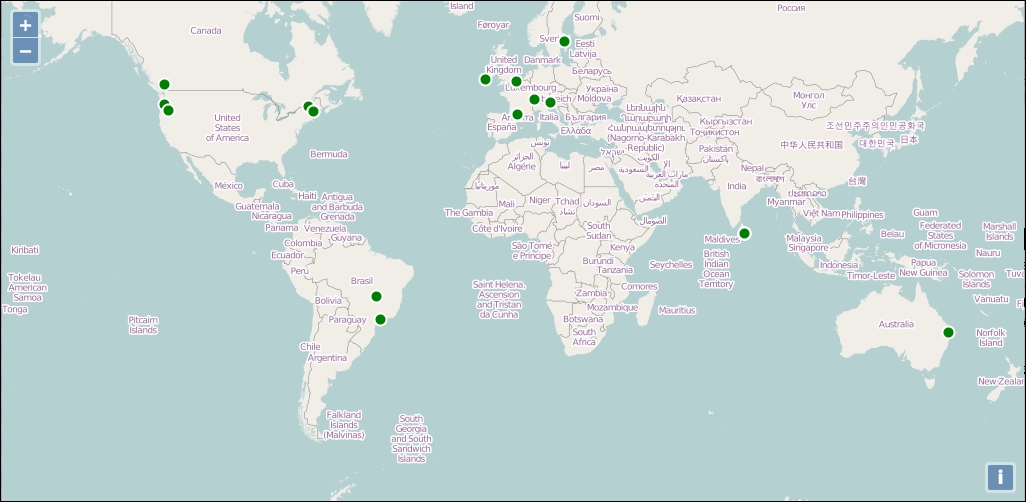

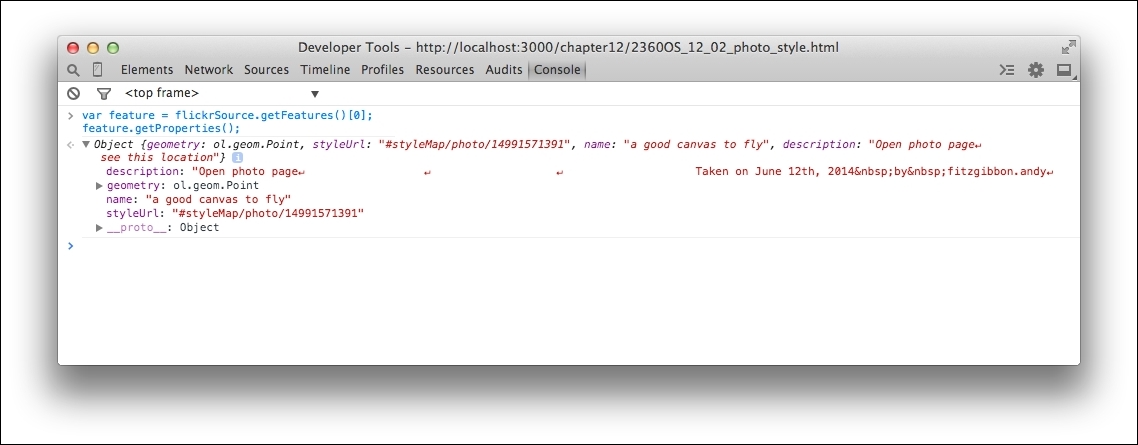

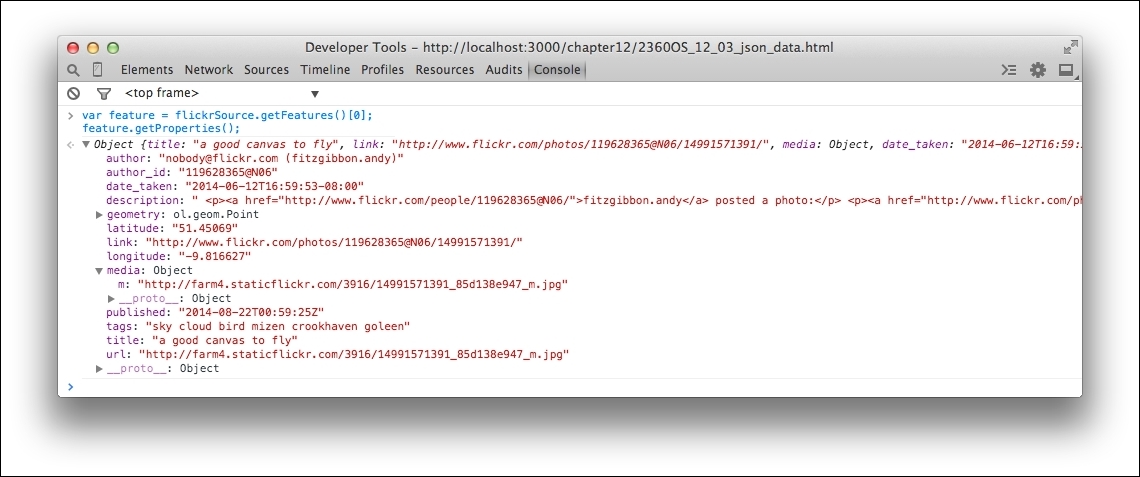

ol.control.Zoom: This displays the zoom buttons in the top-left corner.ol.control.Rotate: This is a button to reset rotation to 0; by default, this is only displayed when the map's rotation is not 0.ol.control.Attribution: This displays attribution text for the layers currently visible in the map. By default, the attributions are collapsed to a single icon in the bottom-right corner and clicking the icon will show the attributions.We will discuss these controls and more in detail in Chapter 9, Taking Control of Controls.