Let's create a basic map using a different projection. Using the usual code from Chapter 1, Getting Started with OpenLayers, recreate your map object the following way. We'll be specifying the projection property, along with the center and zoom properties. The projection we will use is EPSG:4326, a projection used for world data. Usually, when you don't specify a projection, the default projection in OpenLayers is EPSG:3857 (historically, called EPSG:900913), used by Google Maps and other third-party APIs such as Bing Maps or OpenStreetMap.

- Declare a new layer:

var blueMarbleLayer = new ol.layer.Tile({ source: new ol.source.TileWMS({ url: 'http://maps.boundlessgeo.com/geowebcache/service/wms', params: { 'TILED' : true, 'VERSION': '1.1.1', 'LAYERS': 'bluemarble', 'FORMAT': 'image/jpeg' } }) }); - Then, declare a new view:

var view = new ol.view({ projection: 'EPSG:4326', center: [-1.81185, 52.44314], zoom: 6 }); - Now, declare the map object:

var map = new ol.Map({ target: 'map' }); - Add the layer and the view to the map object:

map.addLayer(blueMarbleLayer); map.setView(view);

- Save the file into the usual sandbox folder, we'll refer to it as

chapter7_ex1.html. You should see something like the following:

We just created a map with the EPSG:4326 projection. The process to use another projection is really similar to all previous examples in the book.

One of the main differences is the backend server. It can provide a layer projected in another projection from the default one in OpenLayers 3 library. In our case, it's the source URL, http://maps.boundlessgeo.com/geowebcache/service/wms, from the blueMarbleLayer layer object that permits this.

The other difference is at the view level. In the constructor, we set a new property: projection that refers to wanted EPSG code and we also directly use coordinates from the projection to set the center on our map.

Apart from the code, you'll notice that the example looks quite different from the maps we've made so far. This is because of its projection.

OpenLayers supports any projection, but if you want to use a projection other than EPSG:3857, you must specify this option in the view projection. The default value is EPSG:3857.

If you do not specify this option, the default value is used (most of the other maps so far, have been using the default values).

You can pass to the projection a string with EPSG:yourcode, but you can also give it an ol.proj.Projection object. You can define it manually but most of the time, you will retrieve it from a preconfigured projection setting. We will only cover how to define it when you are using Proj4js, a JavaScript library dedicated to manage projections. As a beginner will not need to work with use cases without EPSG codes. Be careful, as OpenLayers only supports EPSG:4326 and EPSG:3857 (both with a few aliases) out-of-the-box.

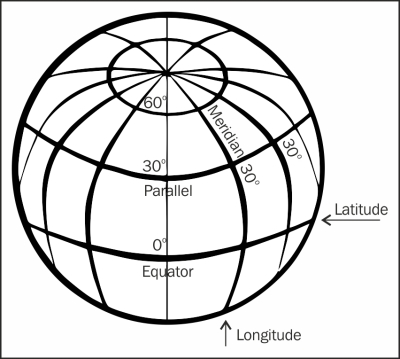

Longitude and latitude are two terms most people are familiar with, though they have limited geographic knowledge or get confused by the two. Let's take a look at the following screenshot and then go over these two terms:

Latitude lines are imaginary lines parallel to the equator, aptly known also as parallels of latitude. Latitude is divided into 90 degrees, or 90 spaces (or cells), above and below the equator. -90° is the South Pole, 0° would be the Equator, and 90° is the North Pole.

Each space, or cell, (from 42° to 43°, for example) is further divided into 60 minutes and each minute is further divided into 60 seconds. The minutes and seconds terminology has little to do with time. In the context of mapping, they are just terms used for precision. The size of a degree of latitude is constant (if calculation bot is based on projected distance). Because they measure 'north to south', OpenLayers considers the y coordinate to be the latitude.

Longitude lines are perpendicular to the lines of latitude. All lines of longitude, also known as meridians of longitude, intersect at the North Pole and South Pole, and unlike latitude, the length of each longitude line is the same. Longitude is divided into 360 degrees, or spaces. Similar to latitude, each space is also divided into 60 minutes, and each minute is divided into 60 seconds. For EPSG:4326, -180 to 0 measures west of the Greenwich meridian, whereas 0 to 180 measures east of Greenwich.

As the space between longitude lines gets smaller, the closer you get to the poles, the size of a degree of longitude changes (when not relying on projected distance). The closer you are to the poles, the lesser time it will take you to walk around the Earth.

With latitude, it makes sense to use the equator as 0°, but with longitude, there is no spot better than to start the 0° mark at. So, while this spot is really arbitrary, the Observatory of Greenwich, England, is today universally considered to be 0° longitude. Because longitude measures east and west, OpenLayers considers the x coordinate to be longitude.