We will implement a procedure that prints a nice illustrating histogram of the numbers a random generator produces. Then, we will run all STL random number generator engines through this procedure and learn from the results. This program contains many repetitive lines, so it might be advantageous to just copy the source code from the code repository accompanying this book on the Internet instead of typing all the repetitive code manually.

- At first, we include all the necessary headers and then declare that we use the std namespace by default:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

#include <random>

#include <iomanip>

#include <limits>

#include <cstdlib>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

- Then we implement a helper function, which helps us maintain and print some statistics for each type of random number engine. It accepts two parameters: the number of partitions and the number of samples. We will see immediately what these are for. The type of random generator is defined via the template parameter RD. The first thing we do in this function is define an alias type for the resulting numeric type of the numbers the generator returns. We also make sure that we have at least 10 partitions:

template <typename RD>

void histogram(size_t partitions, size_t samples)

{

using rand_t = typename RD::result_type;

partitions = max<size_t>(partitions, 10);

- Next, we instantiate an actual generator instance of type RD. Then, we define a divisor variable called div. All random number engines emit random numbers within the range from 0 to RD::max(). The function argument, partitions, allows the caller to choose by how many partitions we divide every random number range. By dividing the largest possible value by the number of partitions, we know how large every partition is:

RD rd;

rand_t div ((double(RD::max()) + 1) / partitions);

- Next, we instantiate a vector of counter variables. It is exactly as large as the number of partitions we have. Then, we get as many random values out of the random engine as the variable samples says. The expression, rd(), gets a random number from the generator and shifts its internal state to prepare it for returning the next random number. By dividing every random number by div, we get the partition number it falls into and can increment the right counter in the vector of counters:

vector<size_t> v (partitions);

for (size_t i {0}; i < samples; ++i) {

++v[rd() / div];

}

- Now we have a nice coarse-grained histogram of sample values. In order to print it, we need to know a little bit more about its actual counter values. Let's extract its largest value using the max_element algorithm. We then divide this largest counter value by 100. This way, we can divide all the counter values by max_div and print a lot of stars on the terminal without exceeding the width of 100. If the largest counter contains a number less than 100, because we did not use so many samples, we use max in order to get a minimal divisor of 1:

rand_t max_elm (*max_element(begin(v), end(v)));

rand_t max_div (max(max_elm / 100, rand_t(1)));

- Let's now print the histogram to the terminal. Every partition gets its own line on the terminal. By dividing its counter value by max_div and print so many asterisk symbols '*', we get histogram lines that fit into the terminal:

for (size_t i {0}; i < partitions; ++i) {

cout << setw(2) << i << ": "

<< string(v[i] / max_div, '*') << 'n';

}

}

- Okay, that's it. Now to the main program. We let the user define how many partitions and samples should be used:

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

if (argc != 3) {

cout << "Usage: " << argv[0]

<< " <partitions> <samples>n";

return 1;

}

- We then read those variables from the command line. Of course, the command line consists of strings, which we can convert to numbers using std::stoull (stoull is an abbreviation for string to unsigned long long):

size_t partitions {stoull(argv[1])};

size_t samples {stoull(argv[2])};

- Now we call our histogram helper function on every random number engine the STL provides. This makes this recipe very long and repetitive. Better copy the example from the Internet. The output of this program is really interesting to look at. We start with random_device. This device tries to distribute the randomness equally over all the possible values:

cout << "random_device" << 'n';

histogram<random_device>(partitions, samples);

- The next random engine we try is default_random_engine. What kind of engine this type refers to is implementation-specific. It can be any of the following random engines:

cout << "ndefault_random_engine" << 'n';

histogram<default_random_engine>(partitions, samples);

- Then we try it on all the other engines:

cout << "nminstd_rand0" << 'n';

histogram<minstd_rand0>(partitions, samples);

cout << "nminstd_rand" << 'n';

histogram<minstd_rand>(partitions, samples);

cout << "nmt19937" << 'n';

histogram<mt19937>(partitions, samples);

cout << "nmt19937_64" << 'n';

histogram<mt19937_64>(partitions, samples);

cout << "nranlux24_base" << 'n';

histogram<ranlux24_base>(partitions, samples);

cout << "nranlux48_base" << 'n';

histogram<ranlux48_base>(partitions, samples);

cout << "nranlux24" << 'n';

histogram<ranlux24>(partitions, samples);

cout << "nranlux48" << 'n';

histogram<ranlux48>(partitions, samples);

cout << "nknuth_b" << 'n';

histogram<knuth_b>(partitions, samples);

}

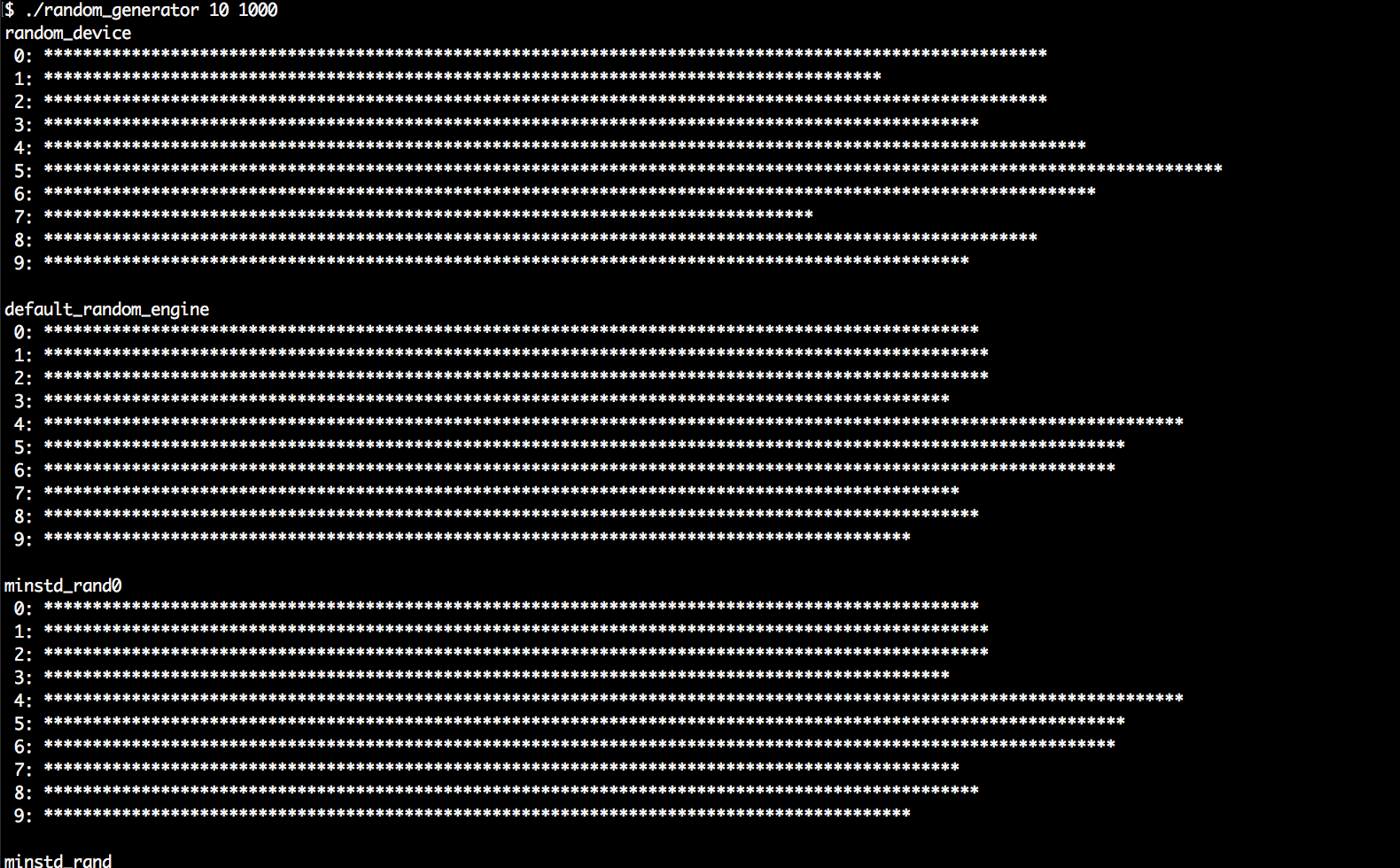

- Compiling and running the program yields interesting results. We will see a long list of output, and we'll see that all the random engines have different characteristics. Let's first run the program with 10 partitions and only 1000 samples:

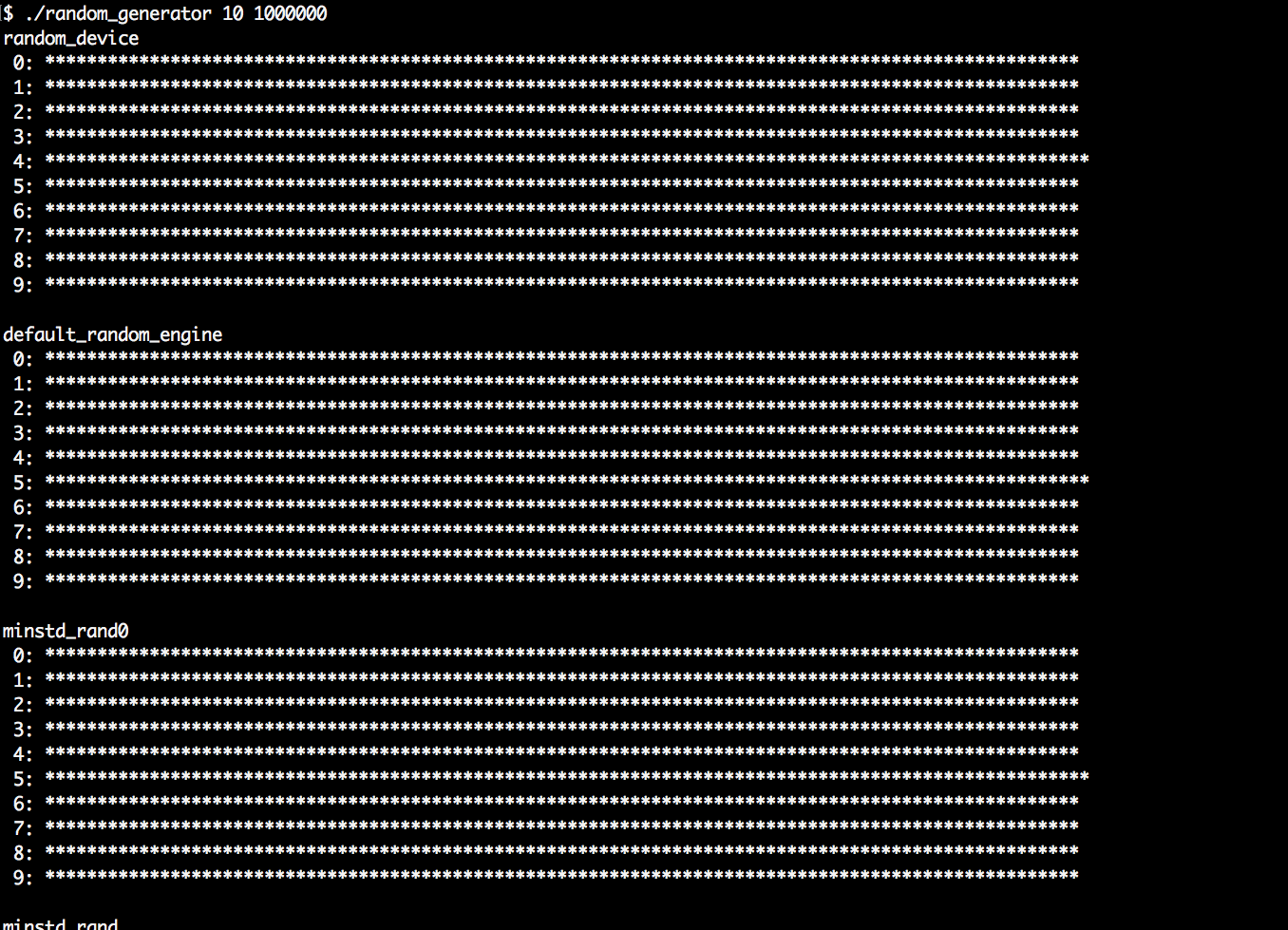

- Then, we run the same program again. This time it is still 10 partitions but 1,000,000 samples. It becomes very obvious that the histograms look much cleaner, when we take more samples from them. This is an important observation: