sudo apt install ruby-dev

Copyright © 2018 Packt Publishing

All rights reserved. No part of this learning path may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles or reviews.

Every effort has been made in the preparation of this learning path to ensure the accuracy of the information presented. However, the information contained in this learning path is sold without warranty, either express or implied. Neither the authors, nor Packt Publishing or its dealers and distributors, will be held liable for any damages caused or alleged to have been caused directly or indirectly by this learning path.

Packt Publishing has endeavored to provide trademark information about all of the companies and products mentioned in this learning path by the appropriate use of capitals. However, Packt Publishing cannot guarantee the accuracy of this information.

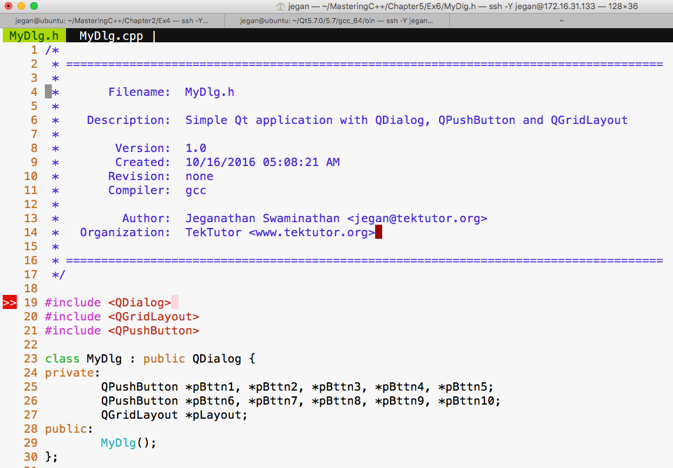

Authors: Jeganathan Swaminathan, Maya Posch, Jacek Galowicz

Reviewer: Brandon James, Louis E. Mauget, Arne Mertz

Content Development Editor: Priyanka Sawant

Graphics: Jisha Chirayal

Production Coordinator: Nilesh Mohite

Published on: April 2018

Production reference: 1060418

Published by Packt Publishing Ltd.

Livery Place

35 Livery Street

Birmingham

B3 2PB, UK.

ISBN 978-1-78883-139-0

Mapt is an online digital library that gives you full access to over 5,000 books and videos, as well as industry leading tools to help you plan your personal development and advance your career. For more information, please visit our website.

Spend less time learning and more time coding with practical eBooks and Videos from over 4,000 industry professionals

Improve your learning with Skill Plans built especially for you

Get a free eBook or video every month

Mapt is fully searchable

Copy and paste, print, and bookmark content

Did you know that Packt offers eBook versions of every book published, with PDF and ePub files available? You can upgrade to the eBook version at www.PacktPub.com and as a print book customer, you are entitled to a discount on the eBook copy. Get in touch with us at service@packtpub.com for more details.

At www.PacktPub.com, you can also read a collection of free technical articles, sign up for a range of free newsletters, and receive exclusive discounts and offers on Packt books and eBooks.

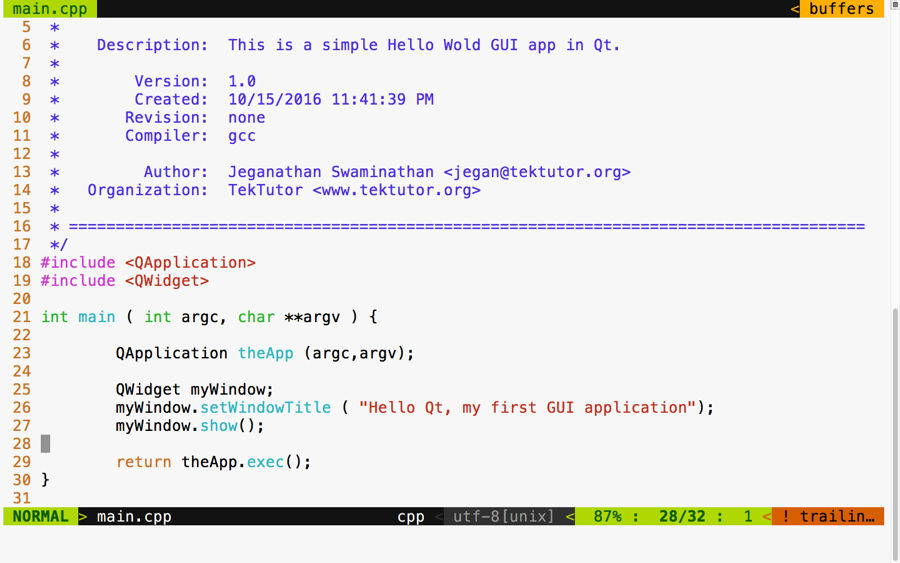

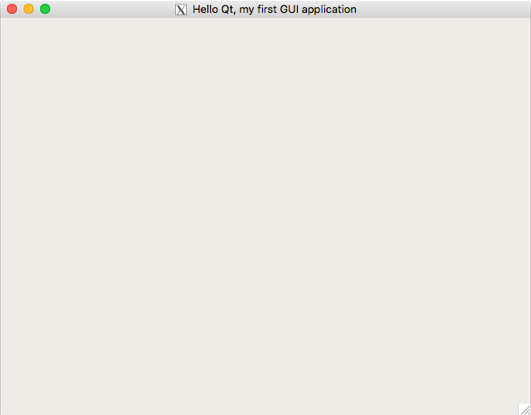

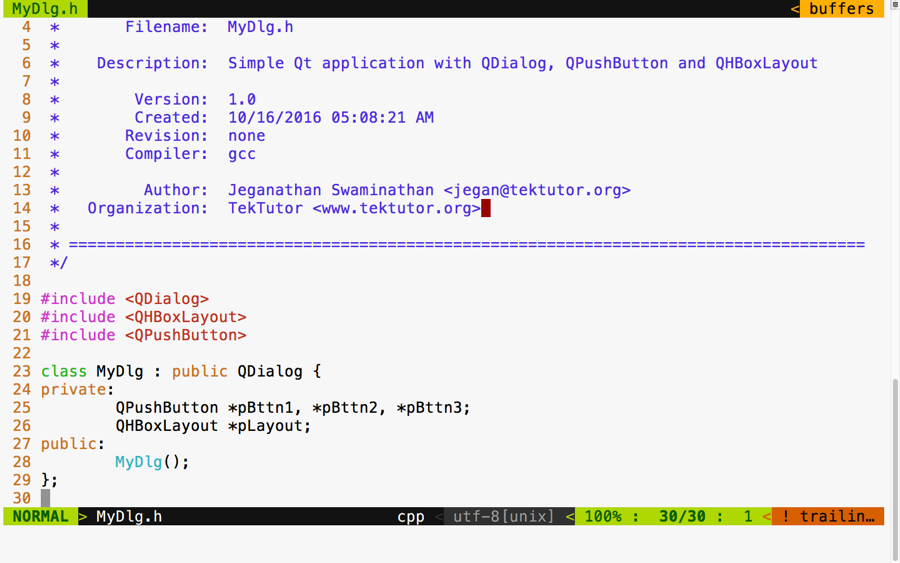

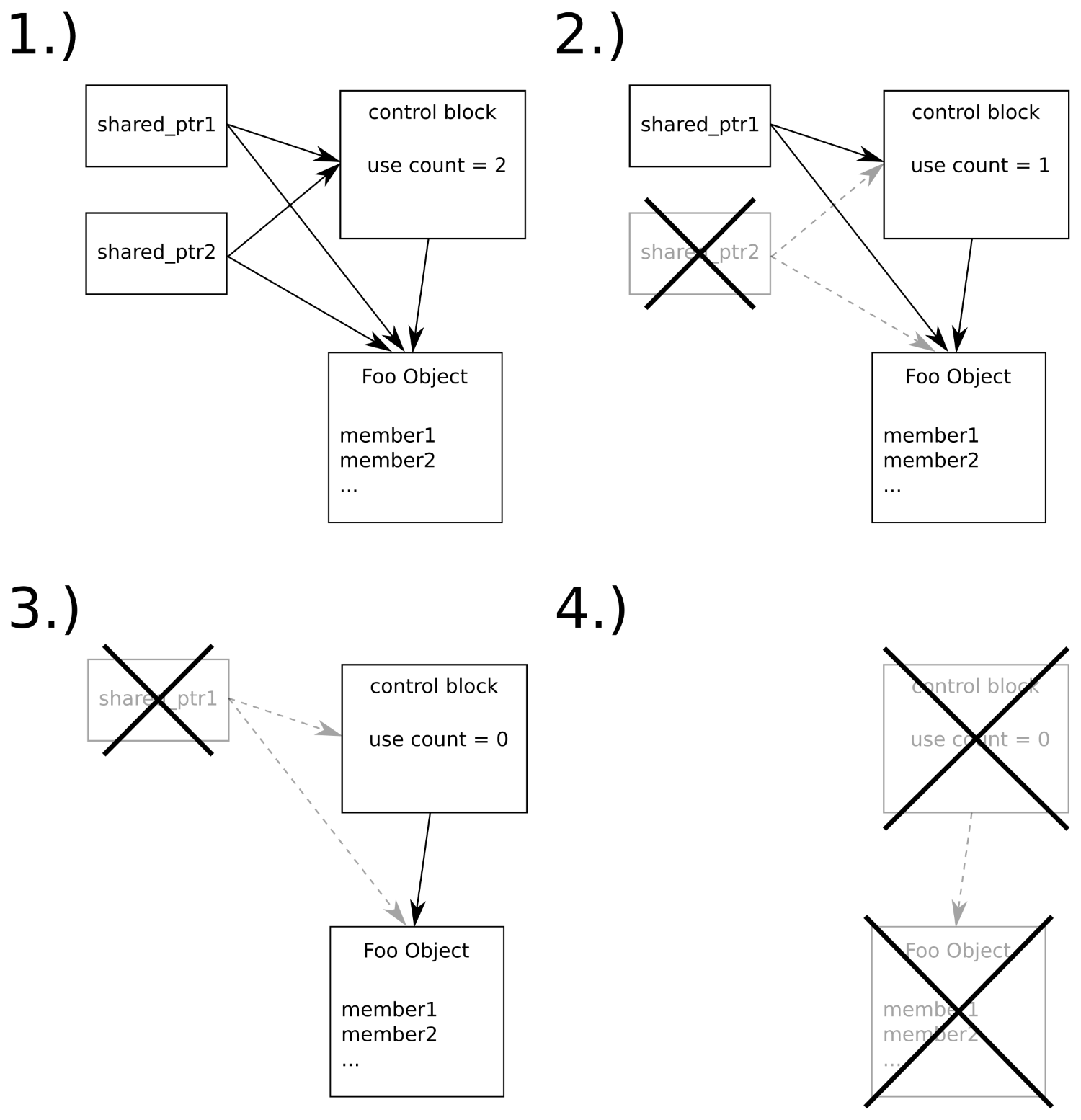

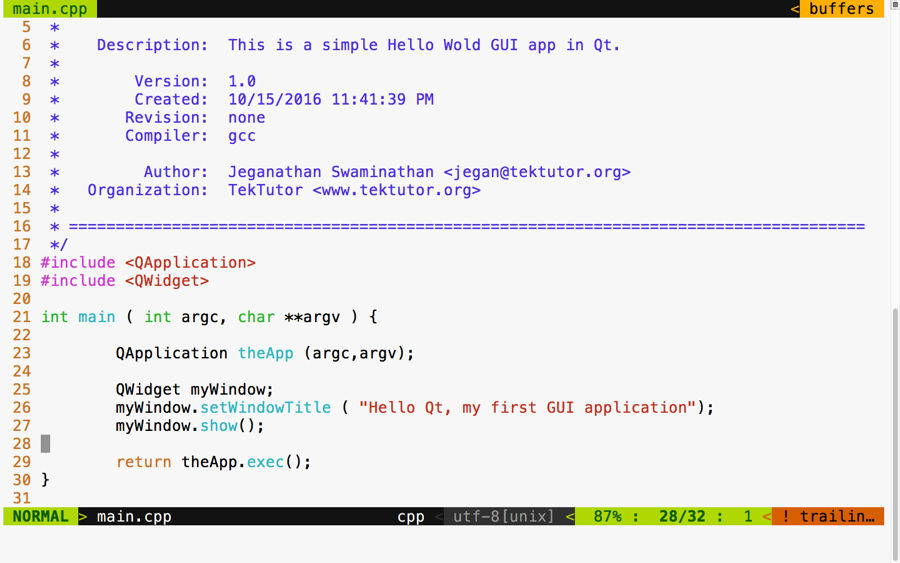

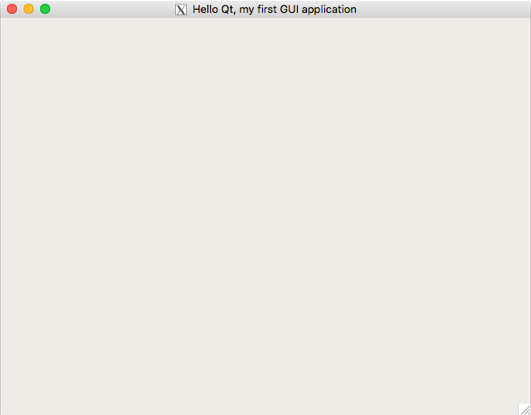

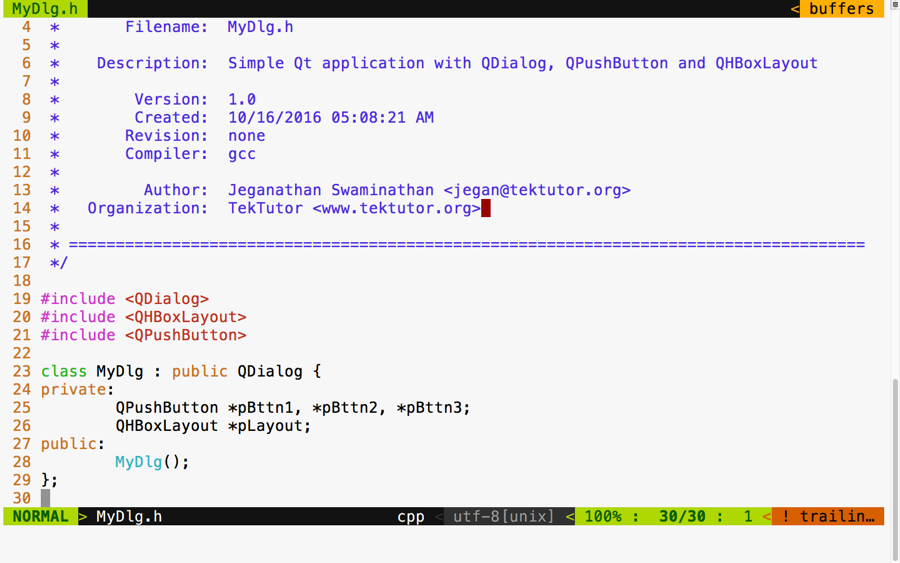

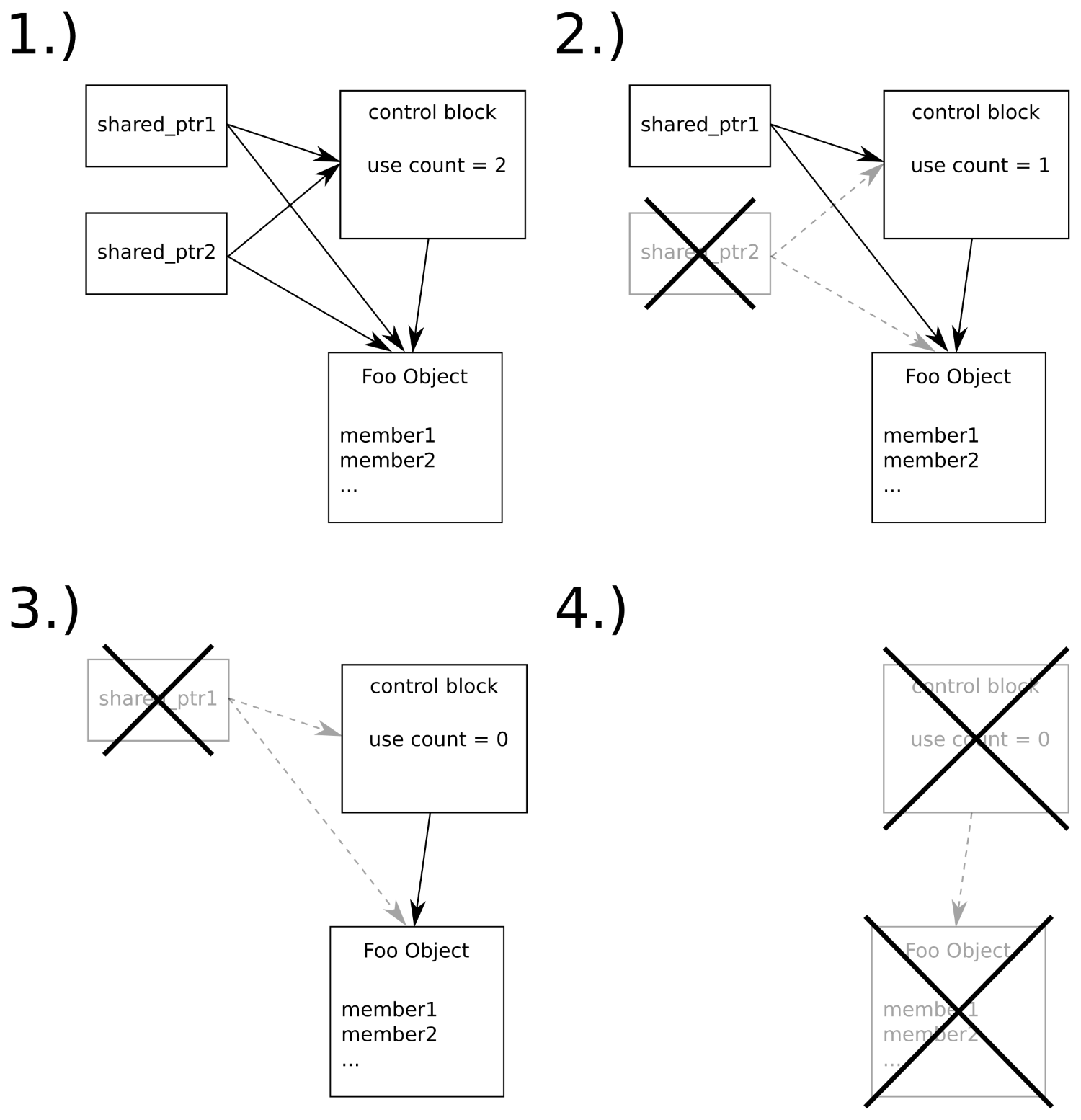

C++ has come a long way and has now been adopted in several contexts. Its key strengths are its software infrastructure and resource-constrained applications. The C++ 17 release will change the way developers write code, and this course will help you master your developing skills with C++. With real-world, practical examples explaining each concept, the course is divided into three modules where will begin by introducing you to the latest features in C++ 17. It encourages clean code practices in C++ in general and demonstrates the GUI app-development options in C++. You’ll get tips on avoiding memory leaks using smart-pointers.

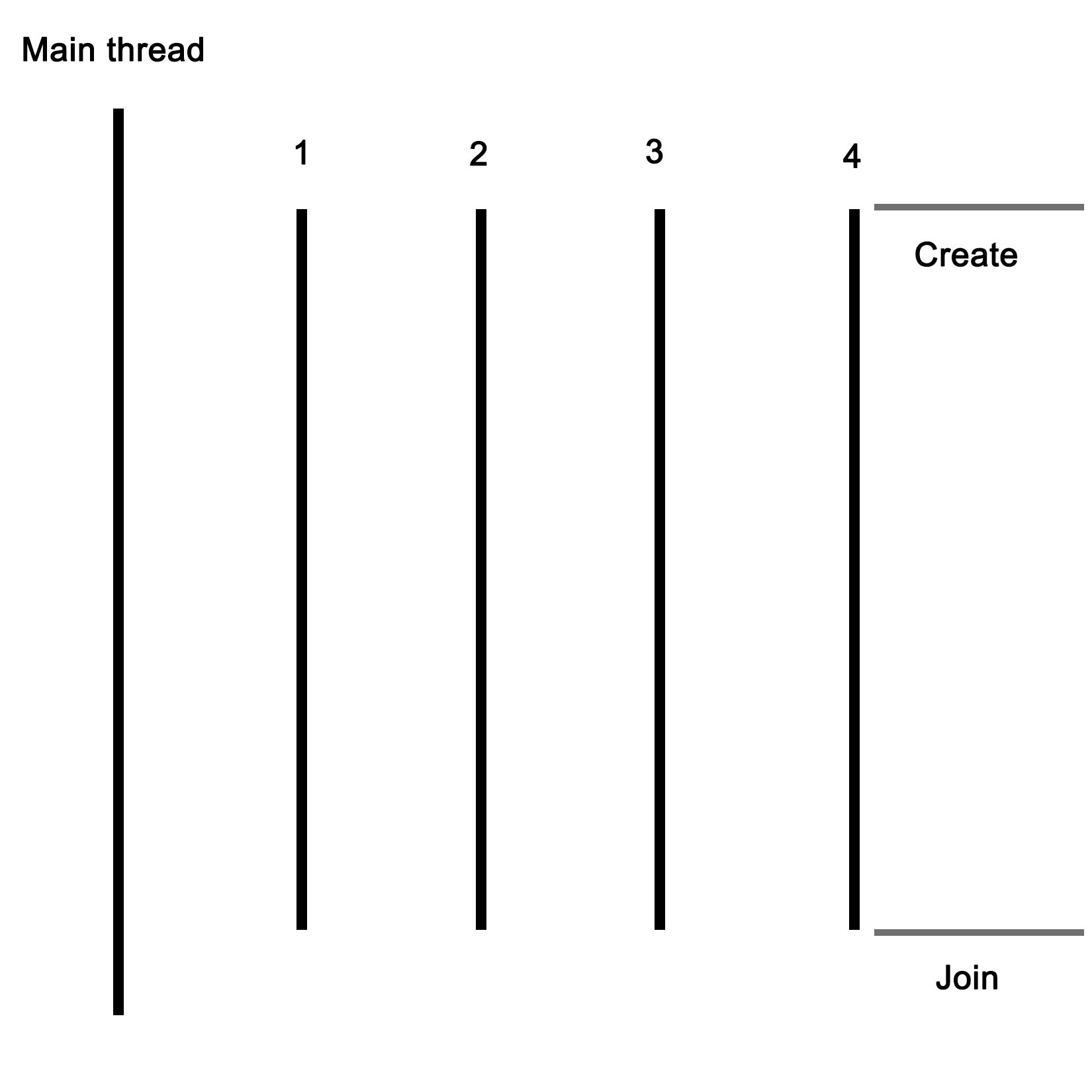

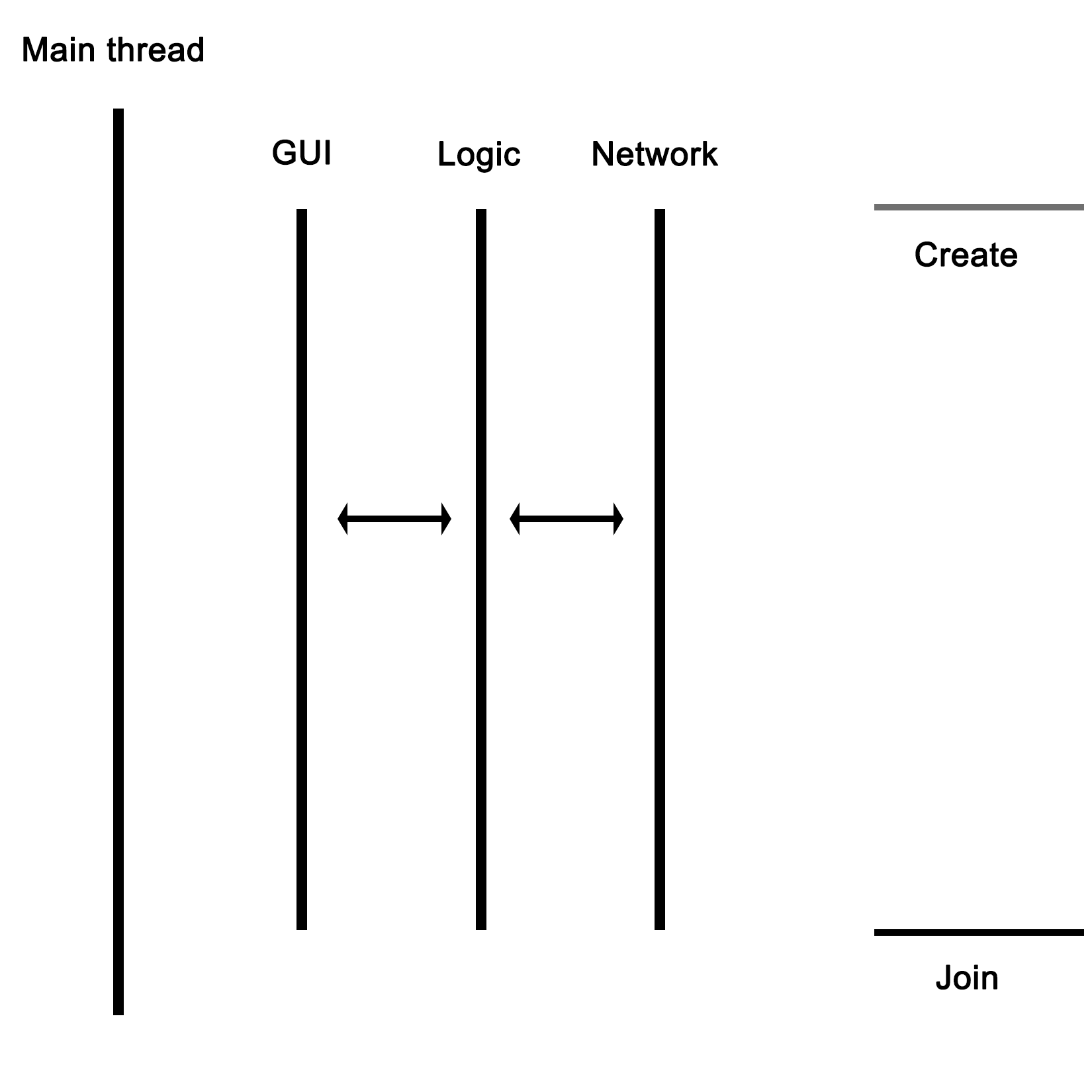

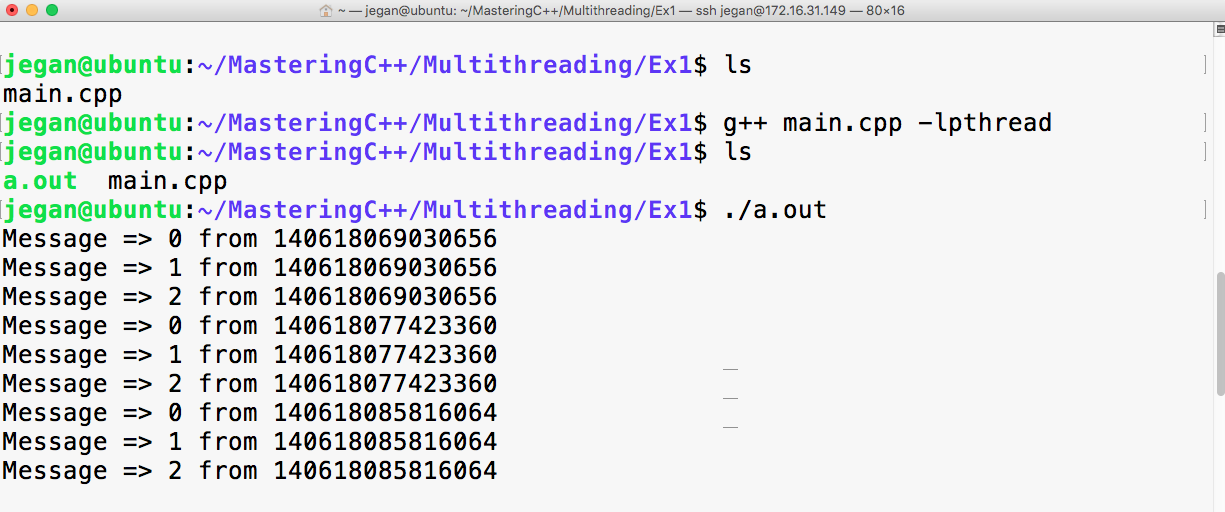

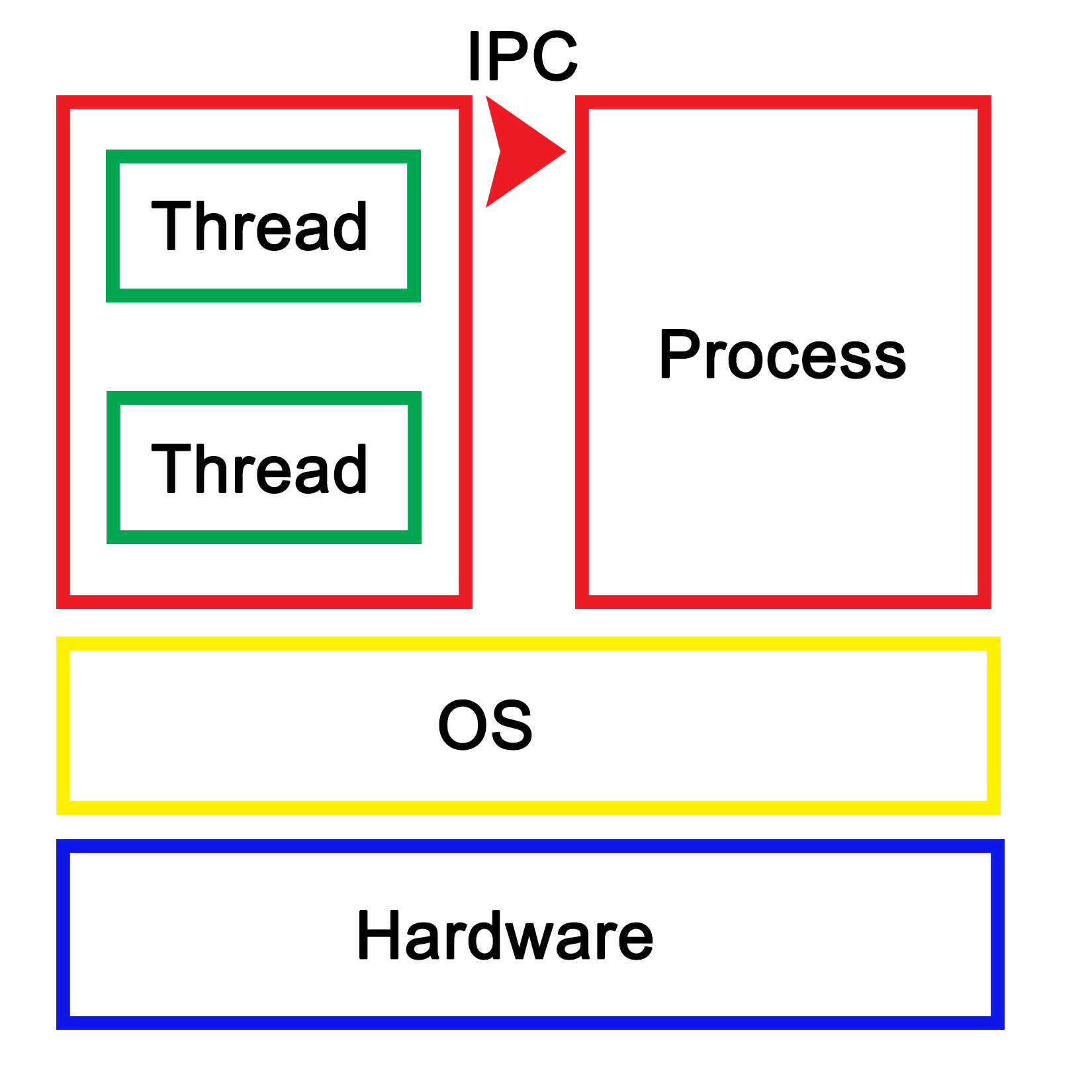

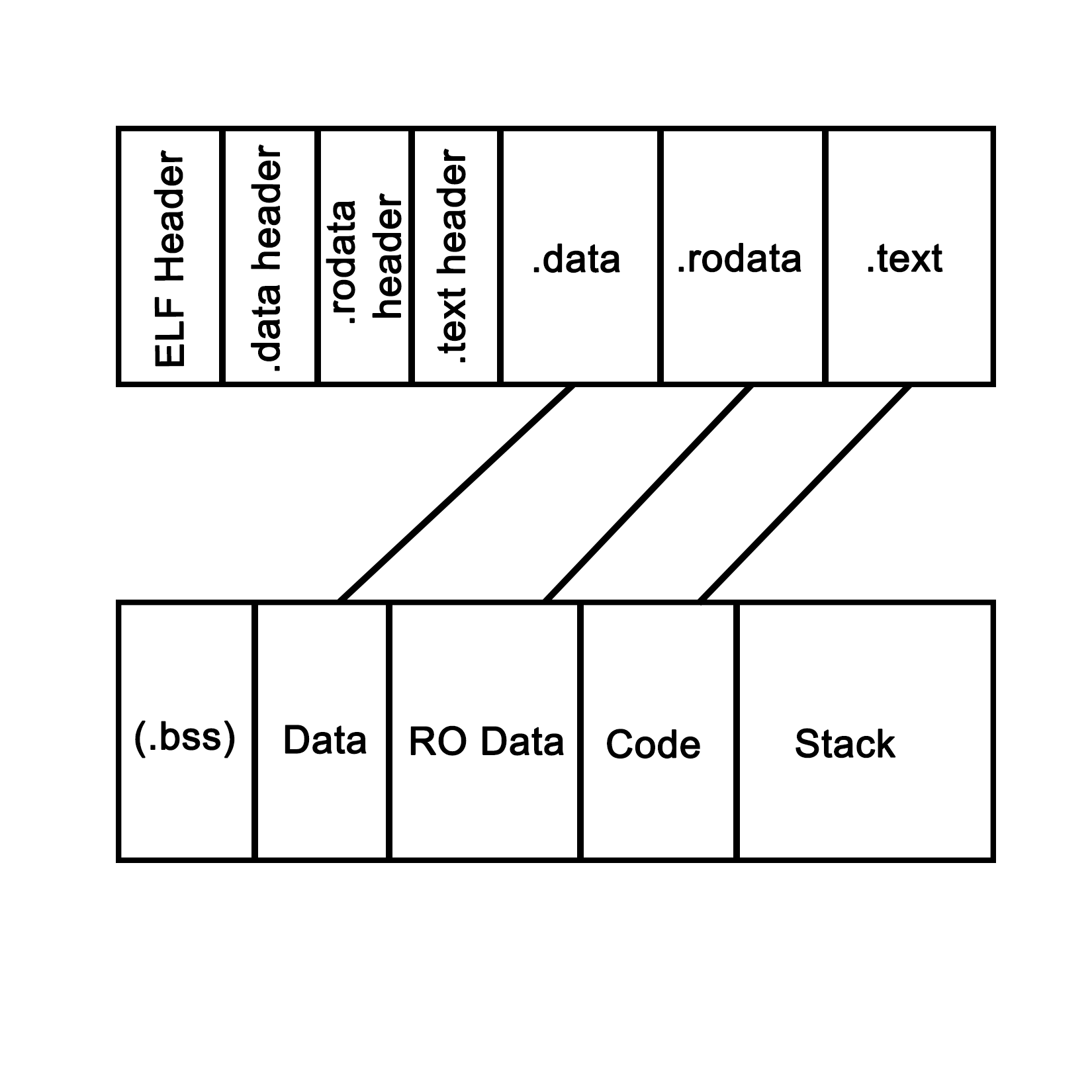

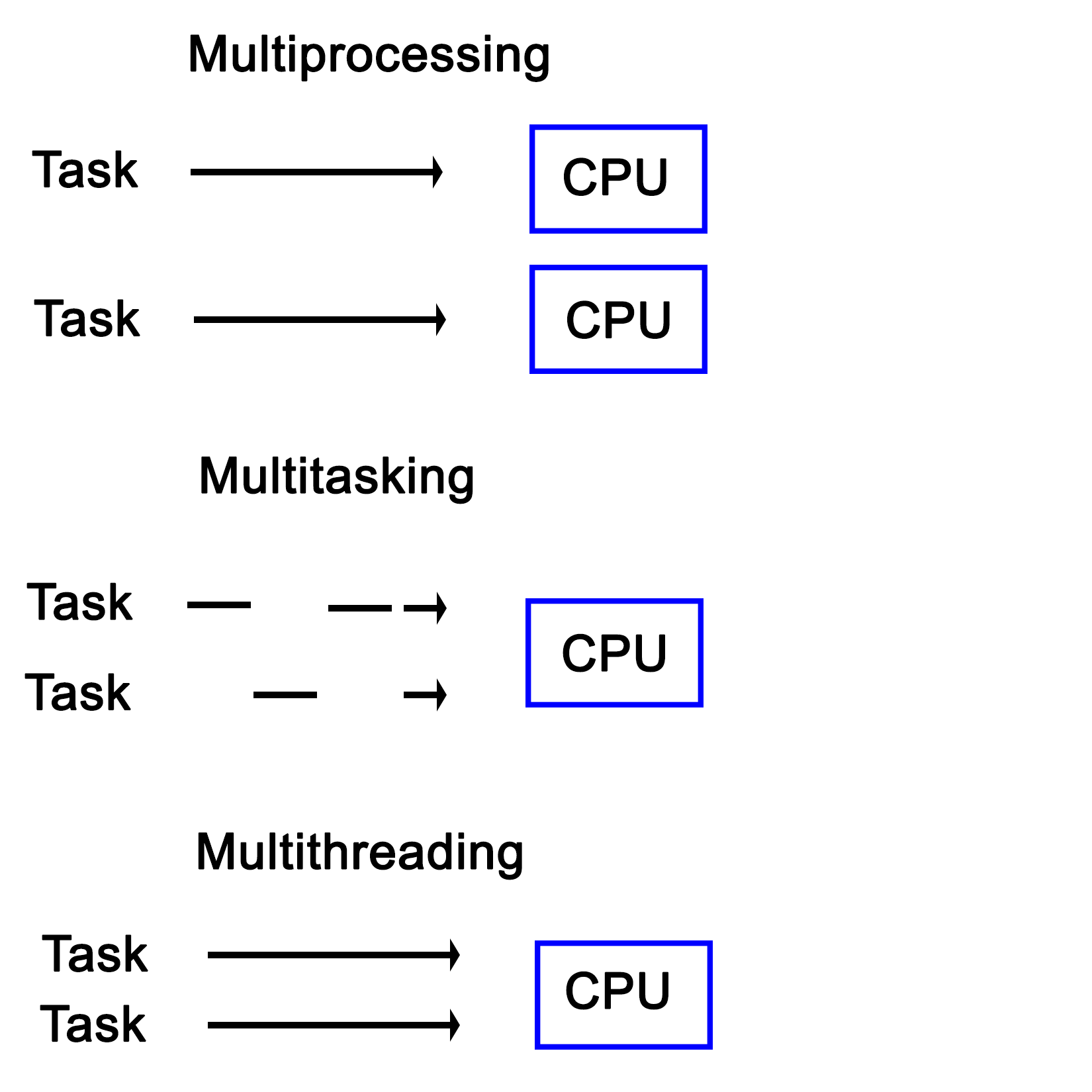

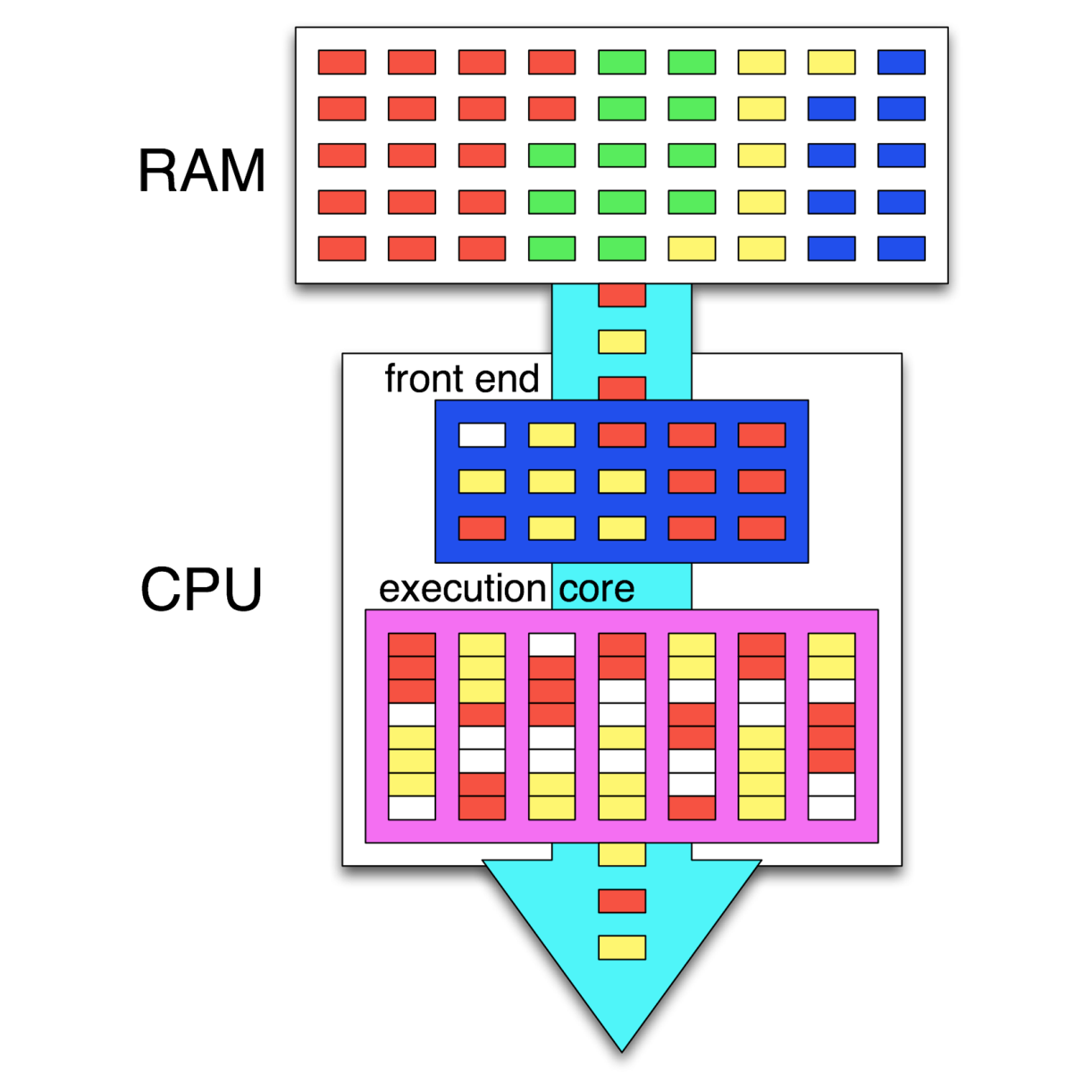

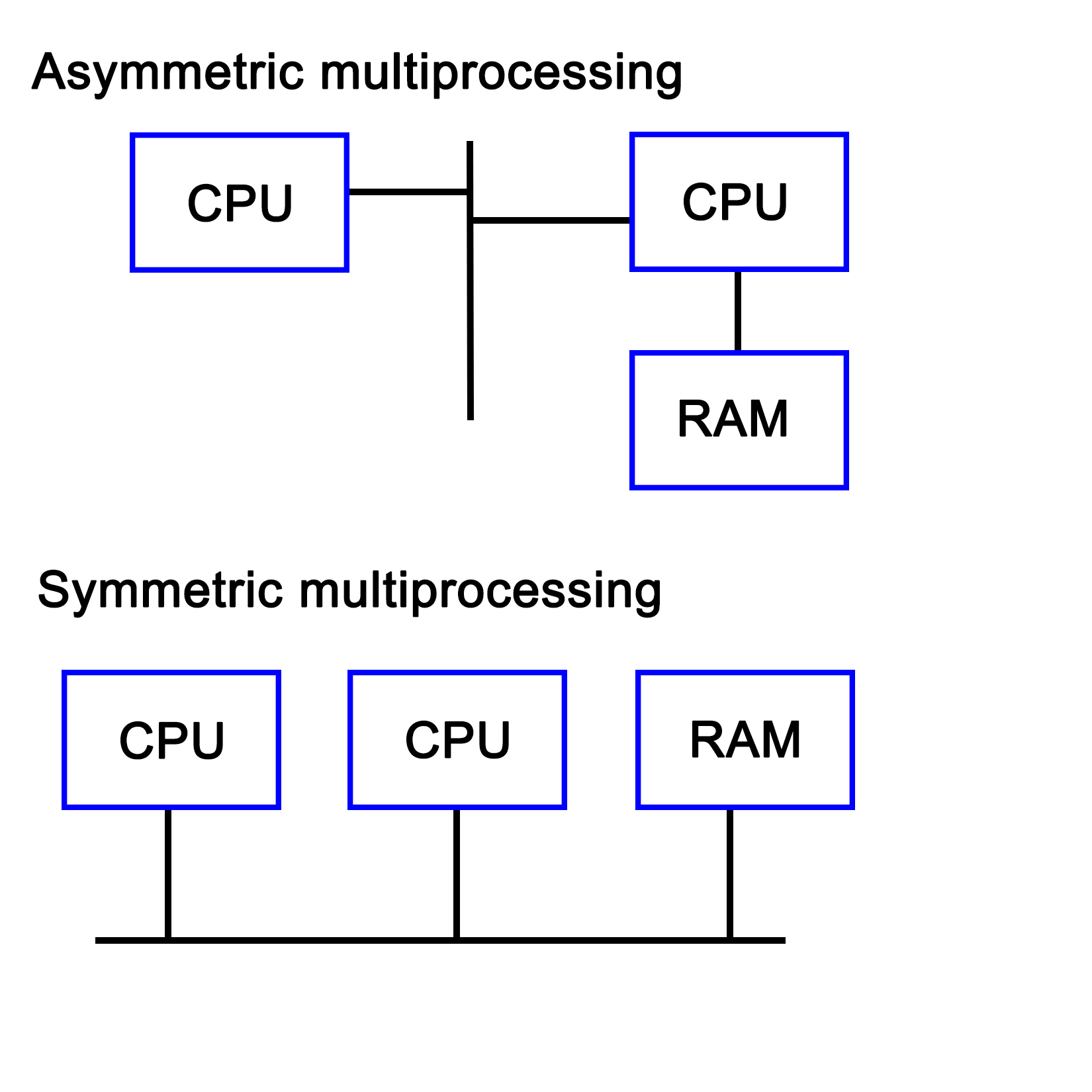

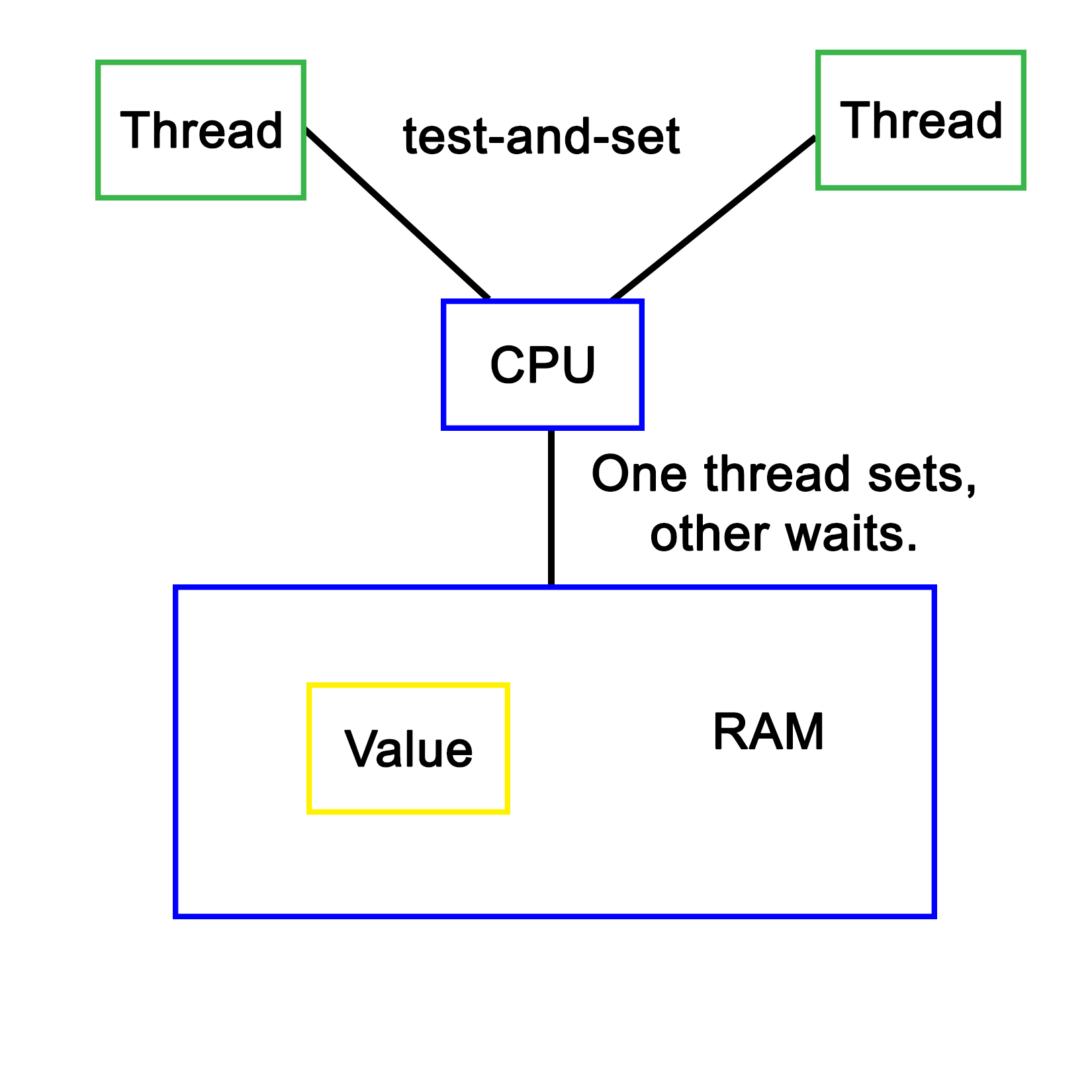

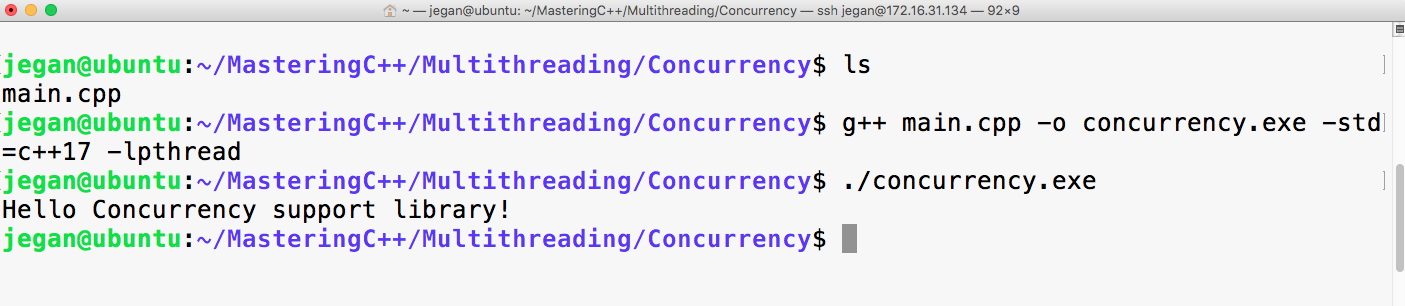

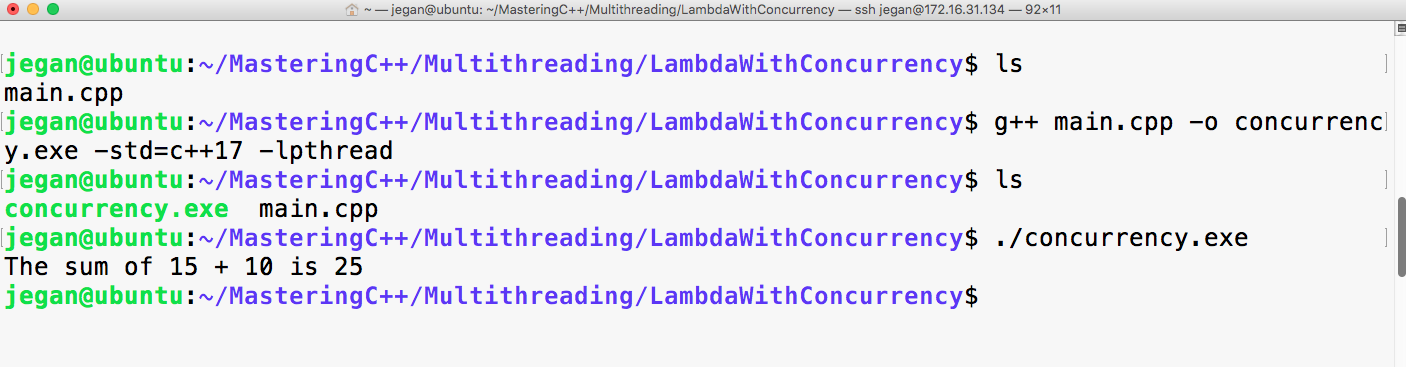

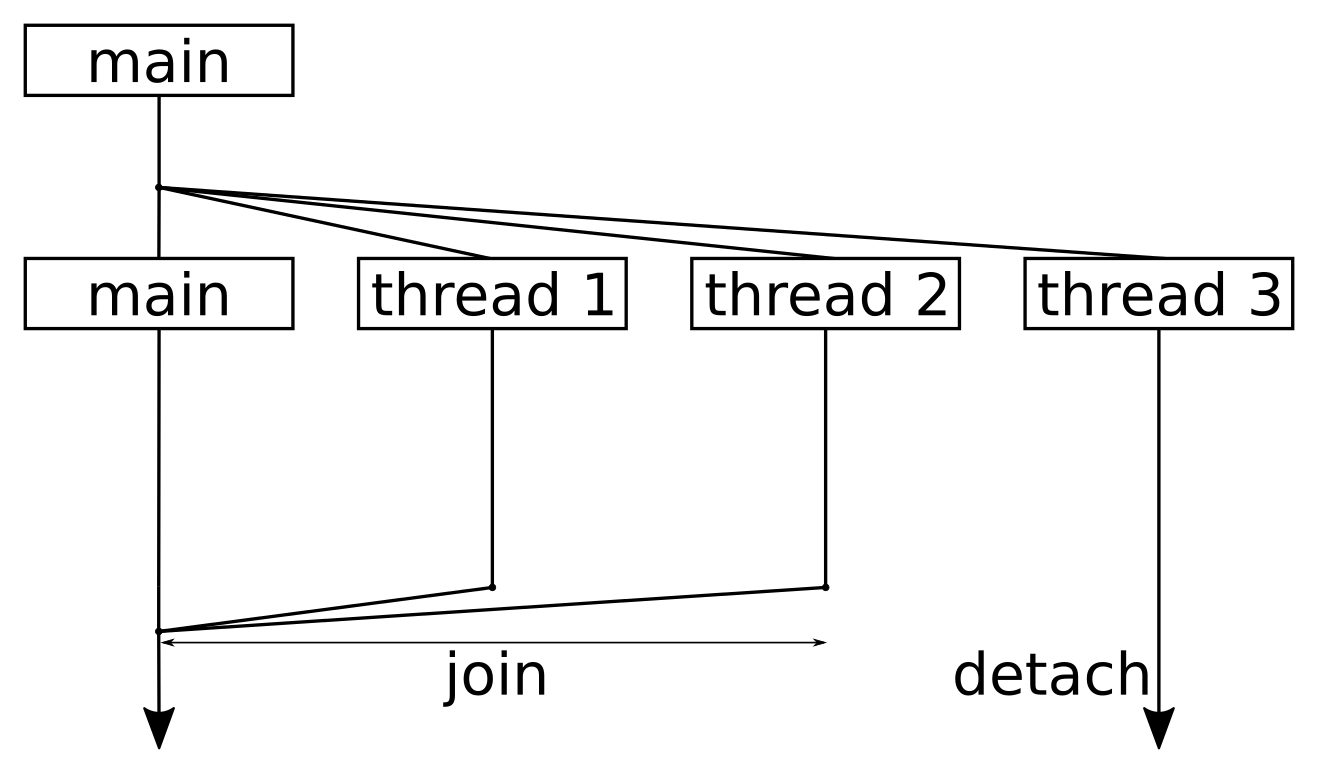

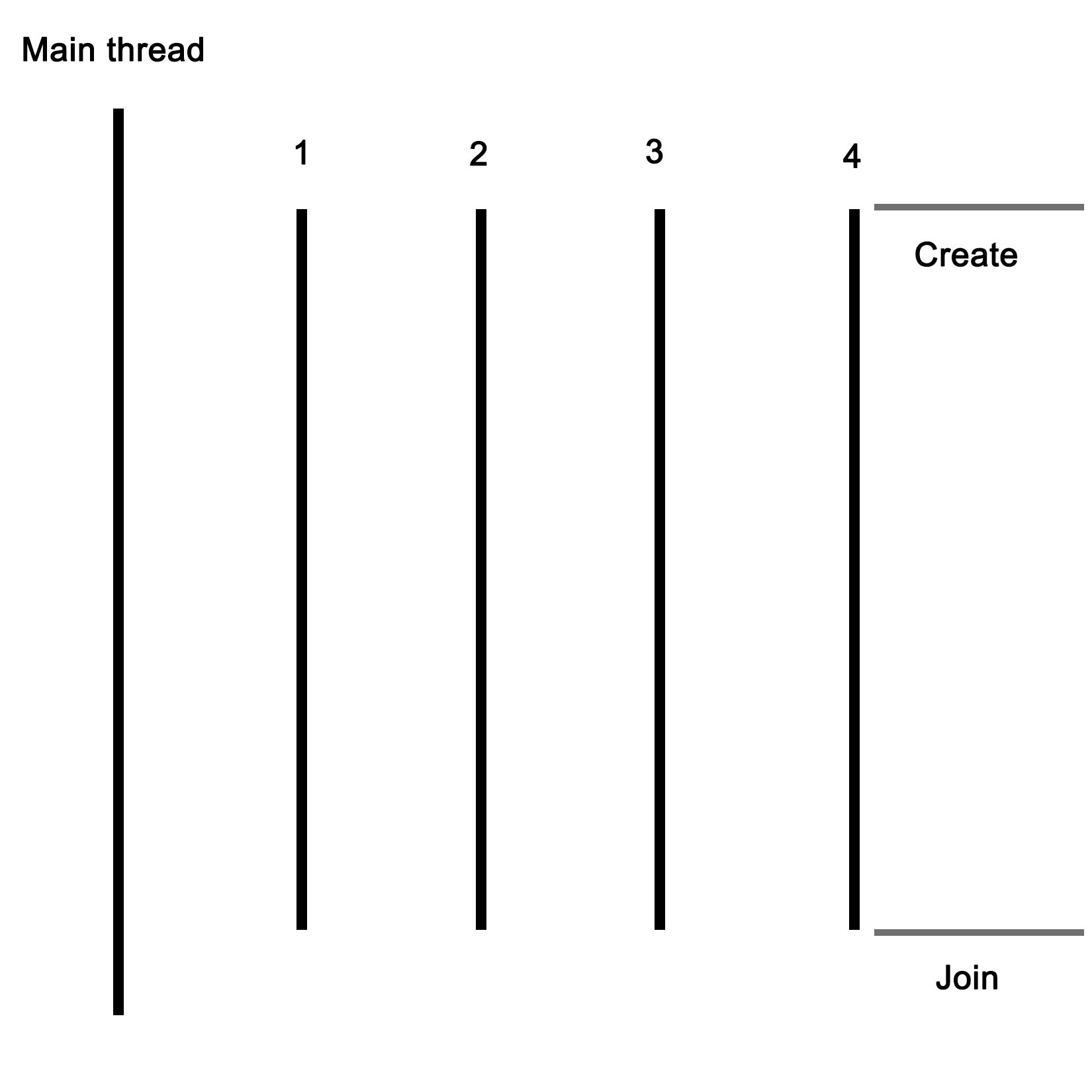

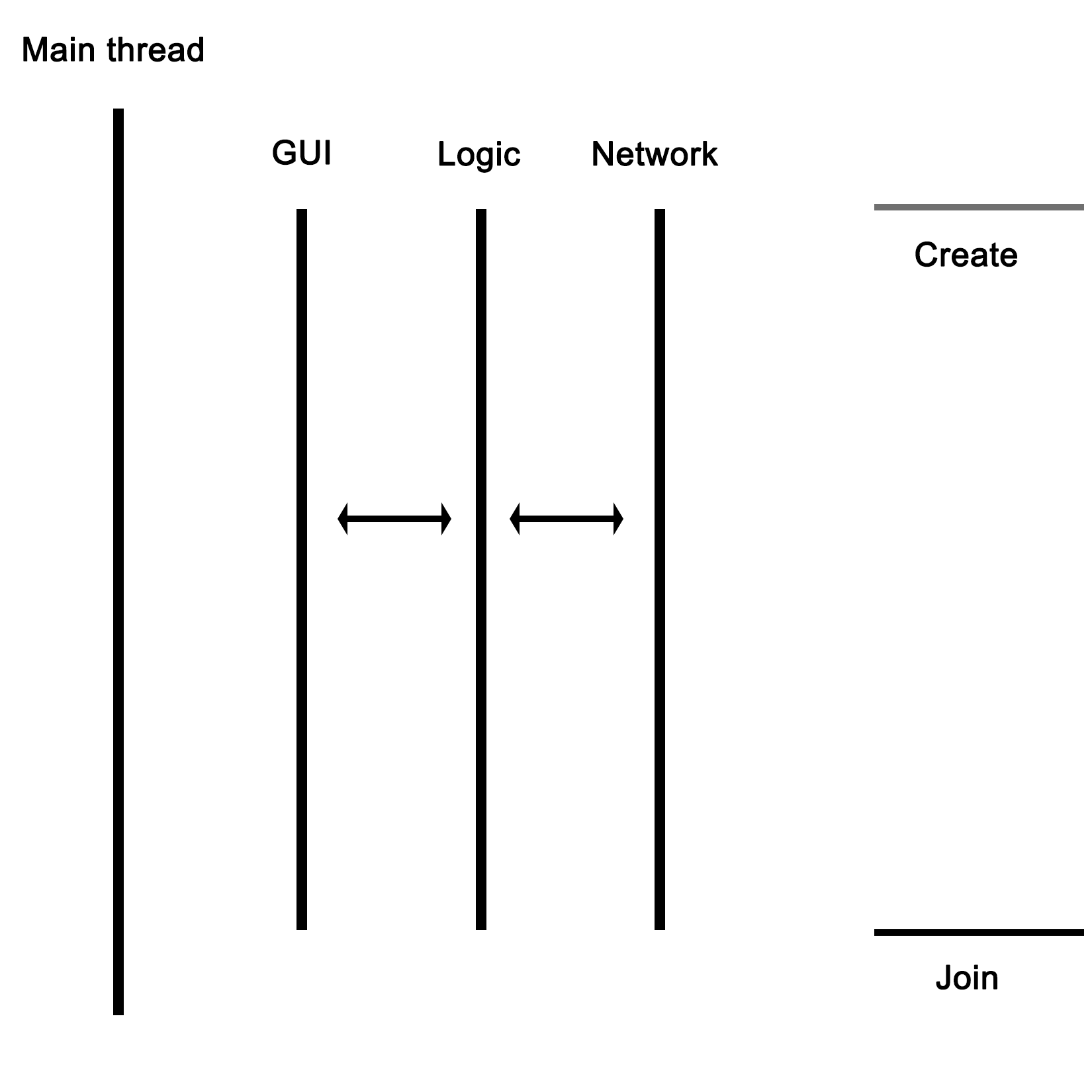

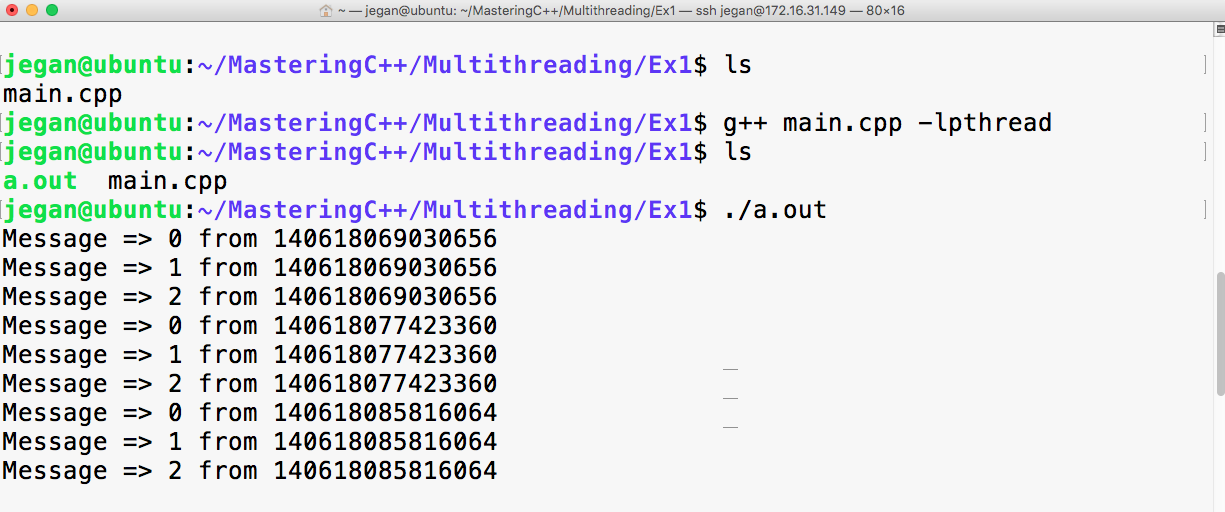

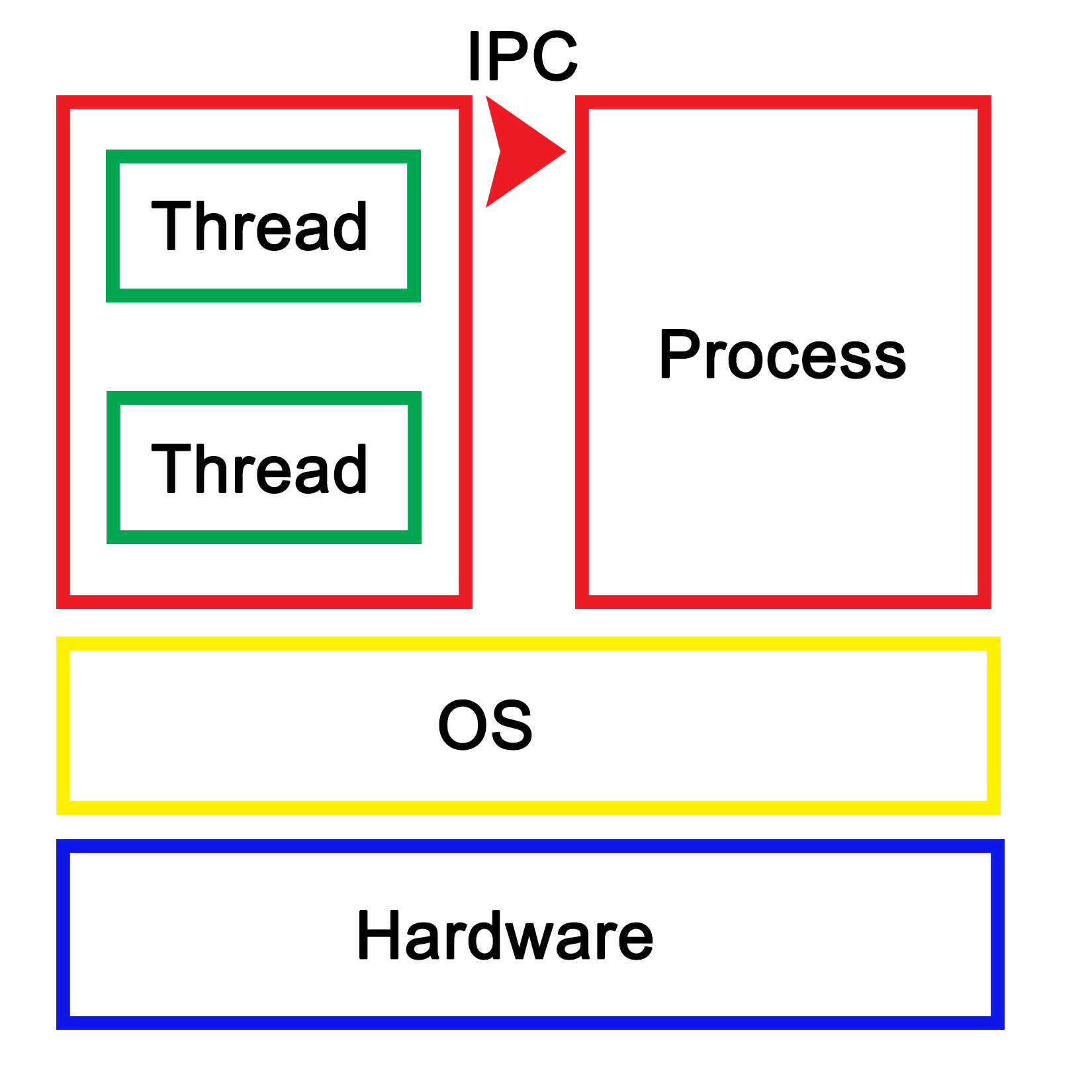

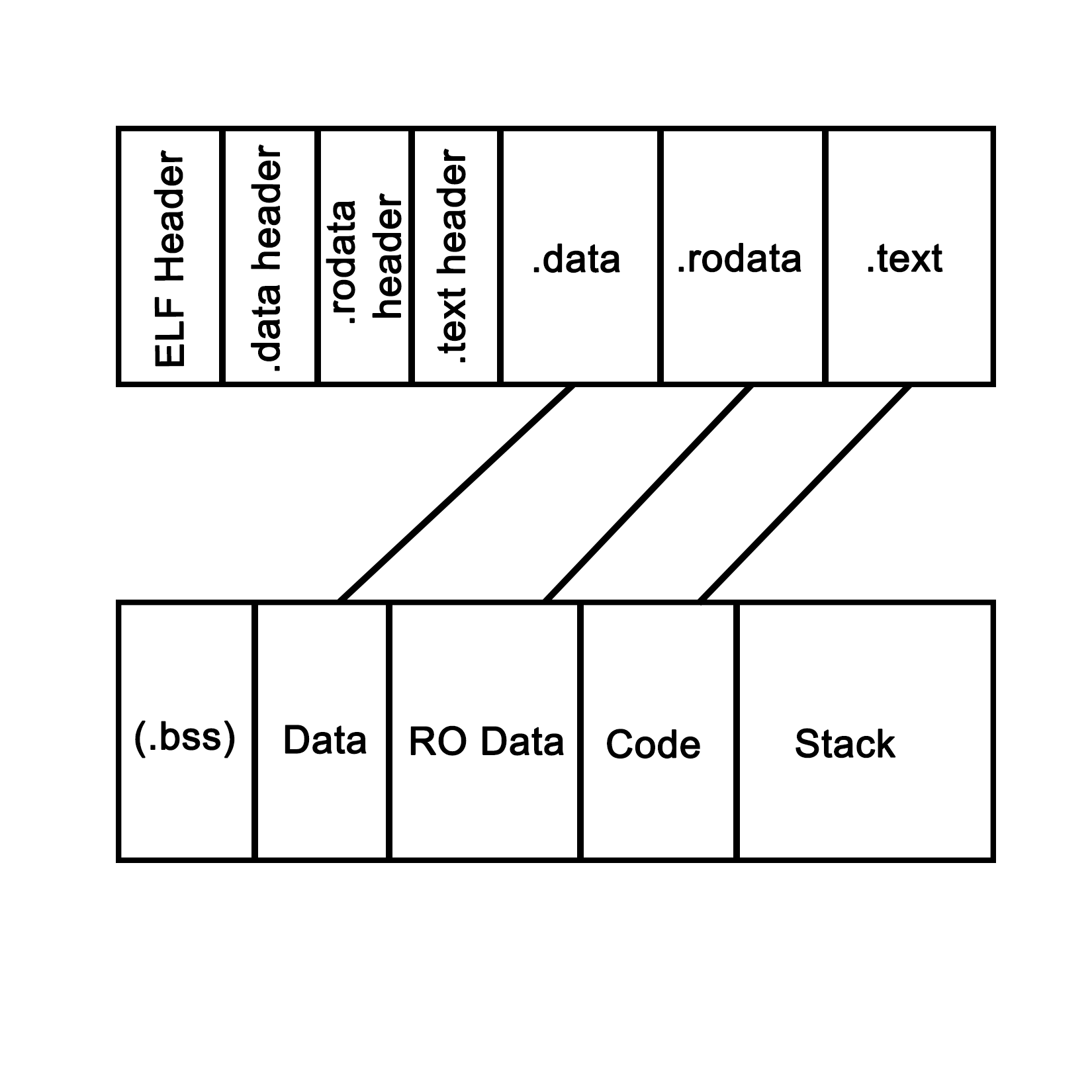

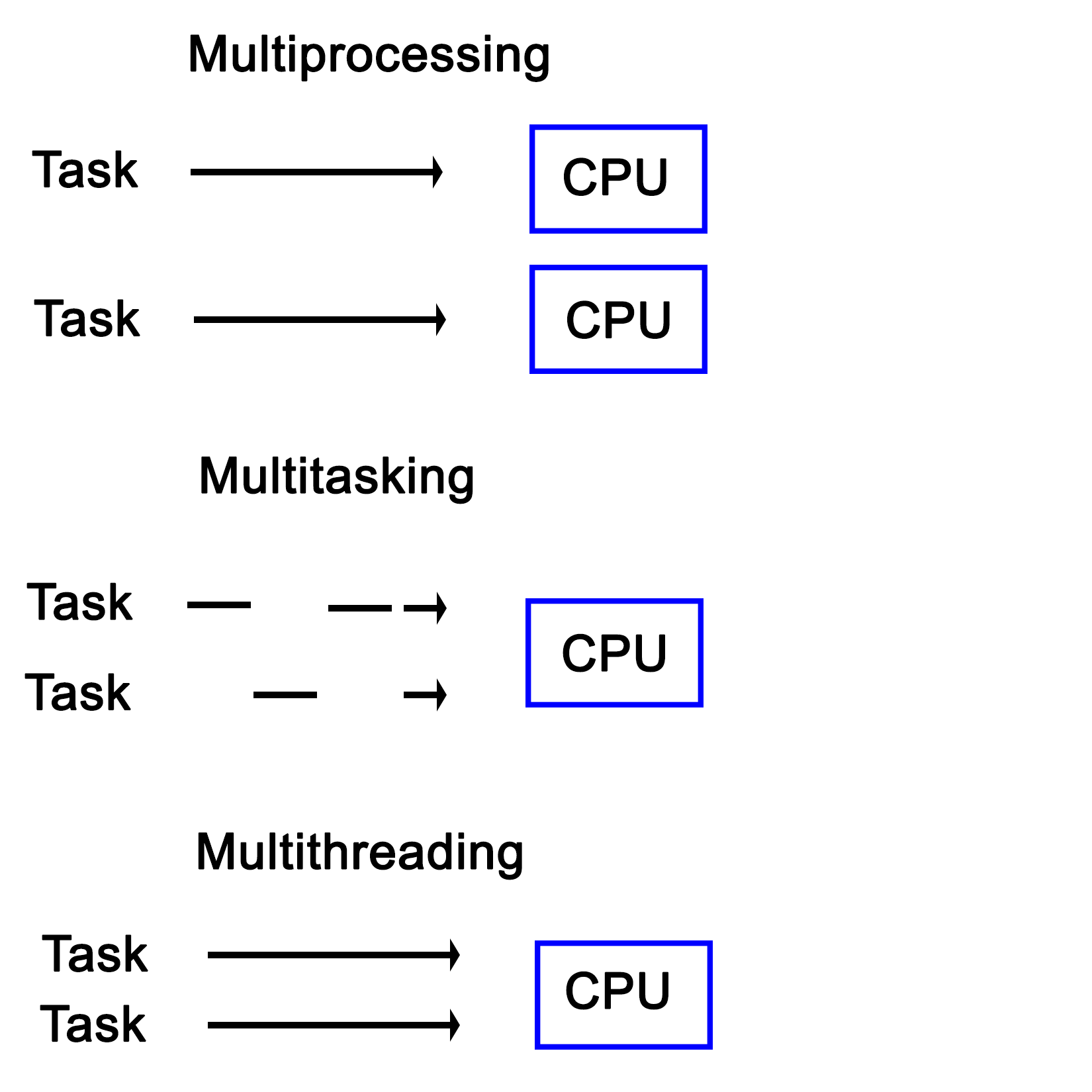

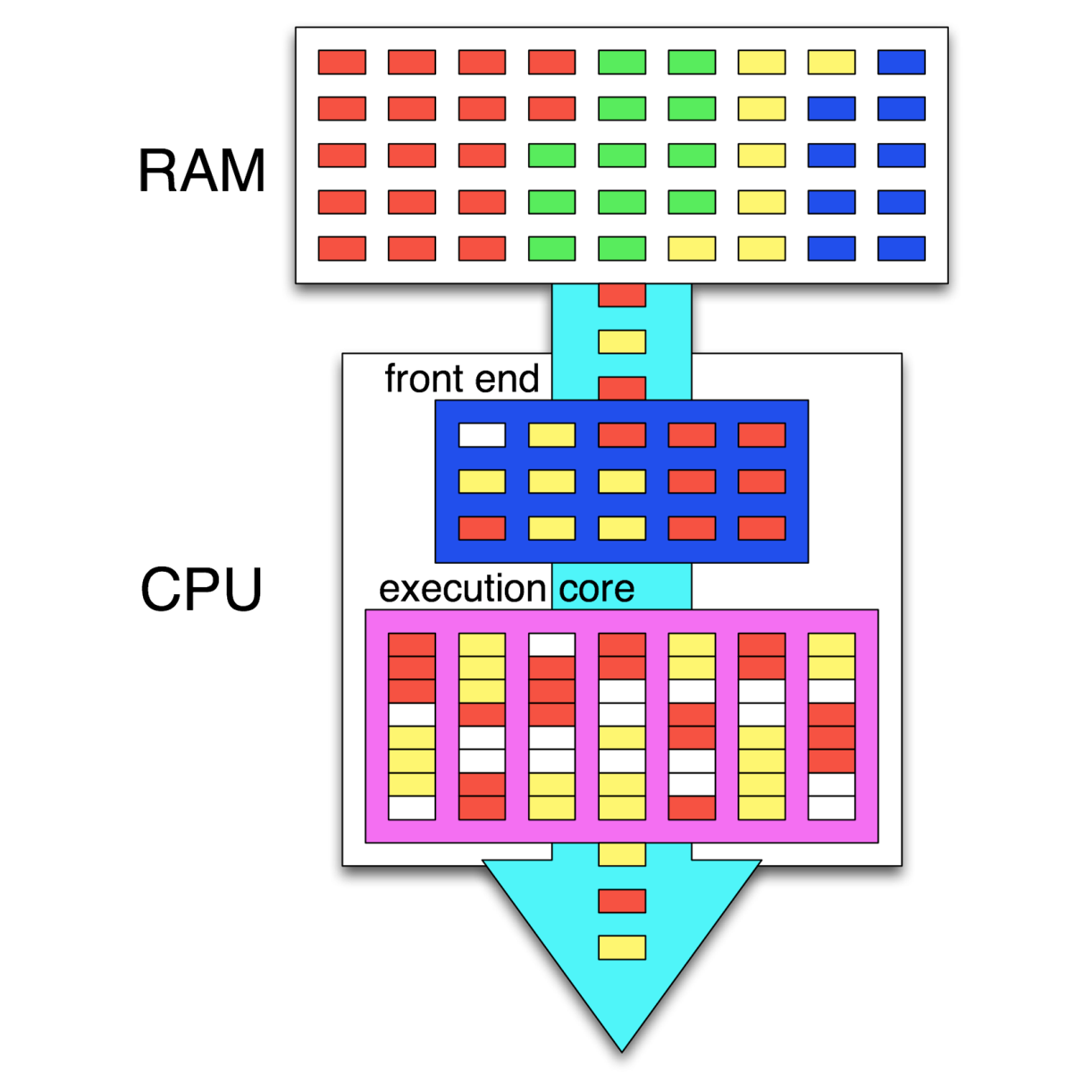

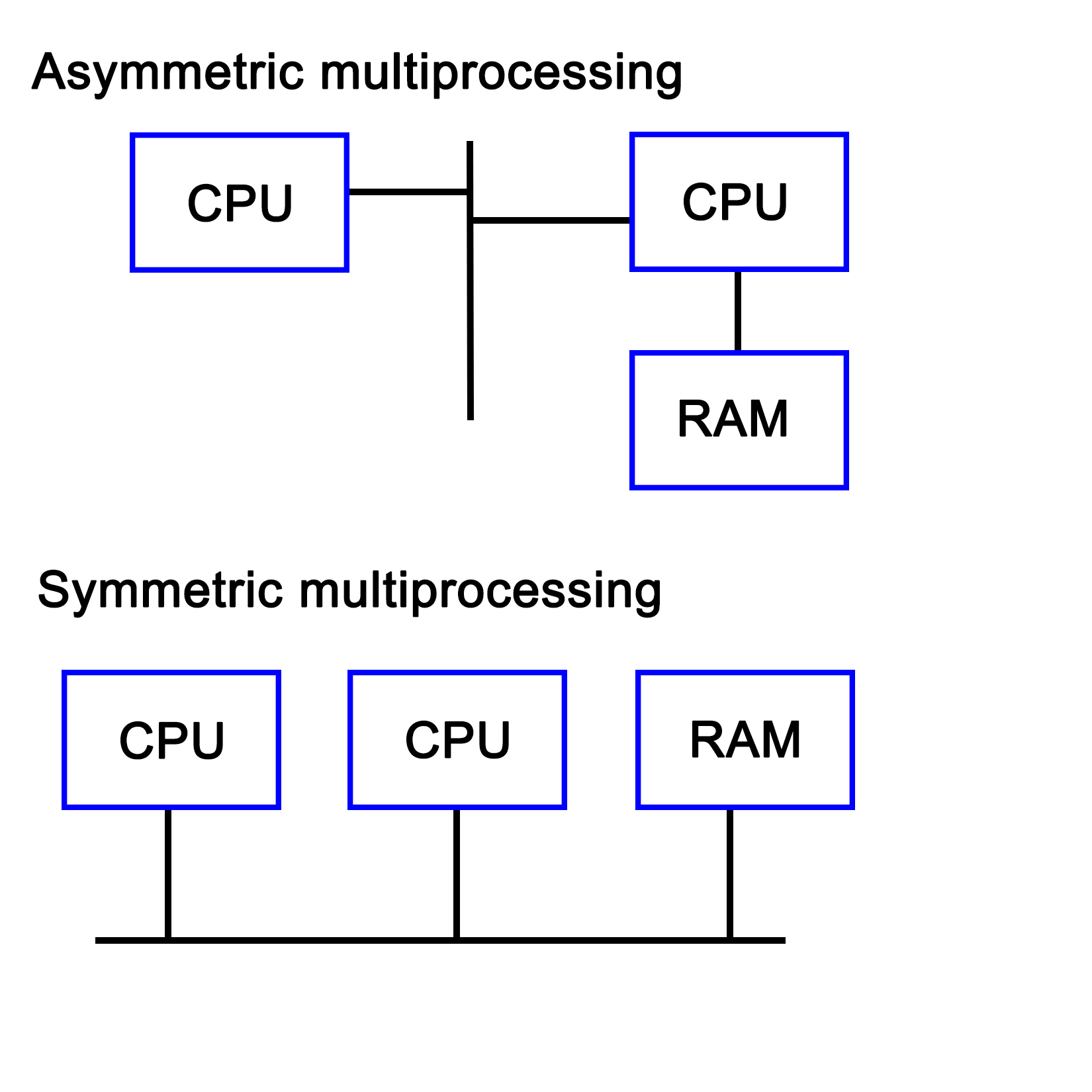

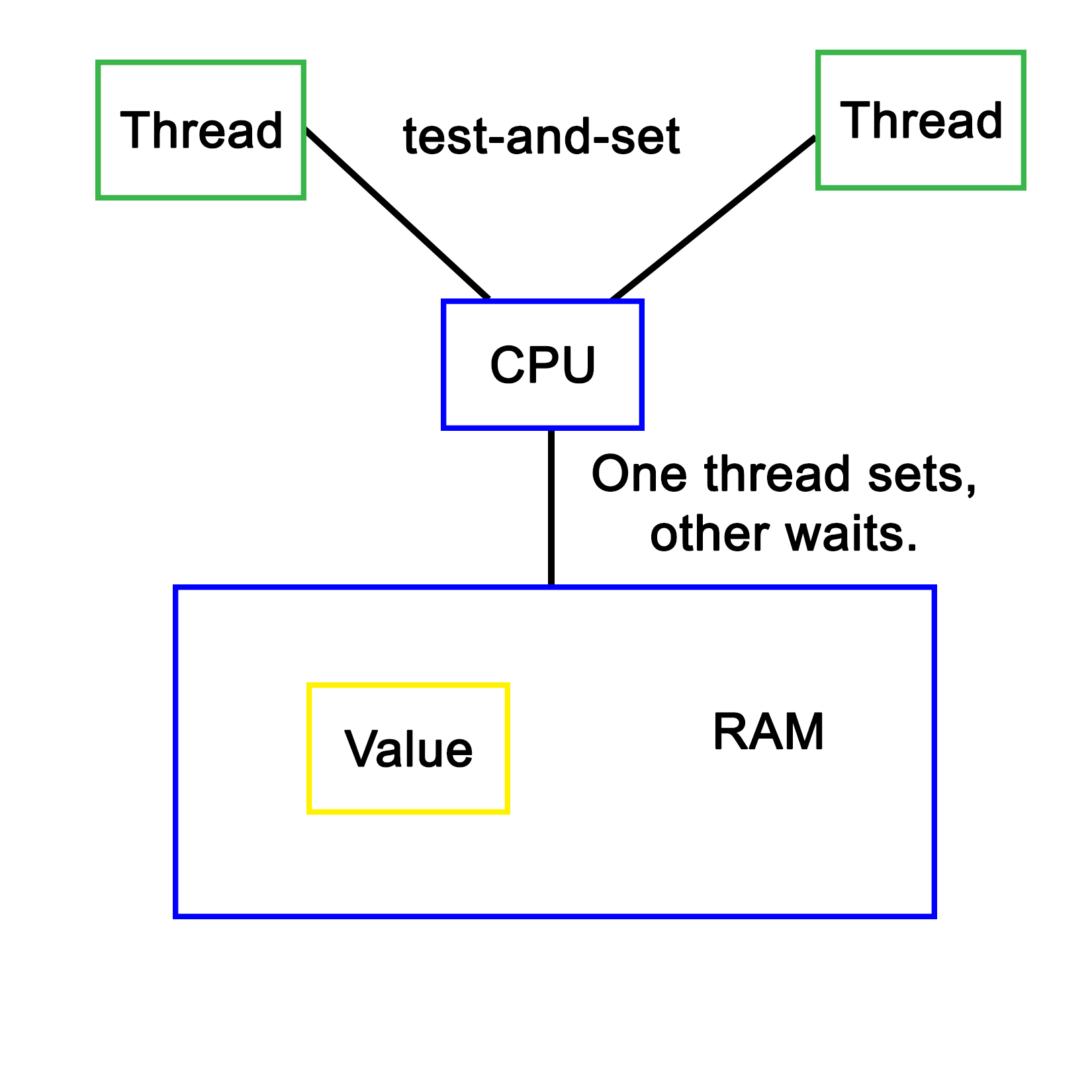

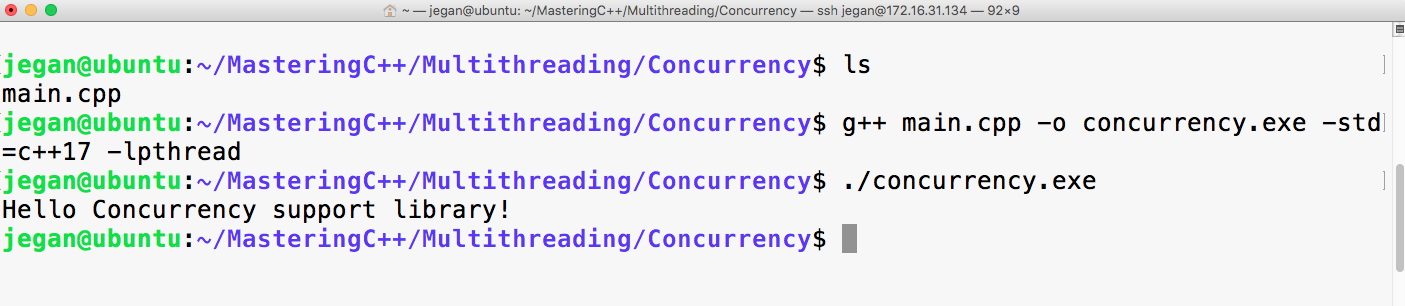

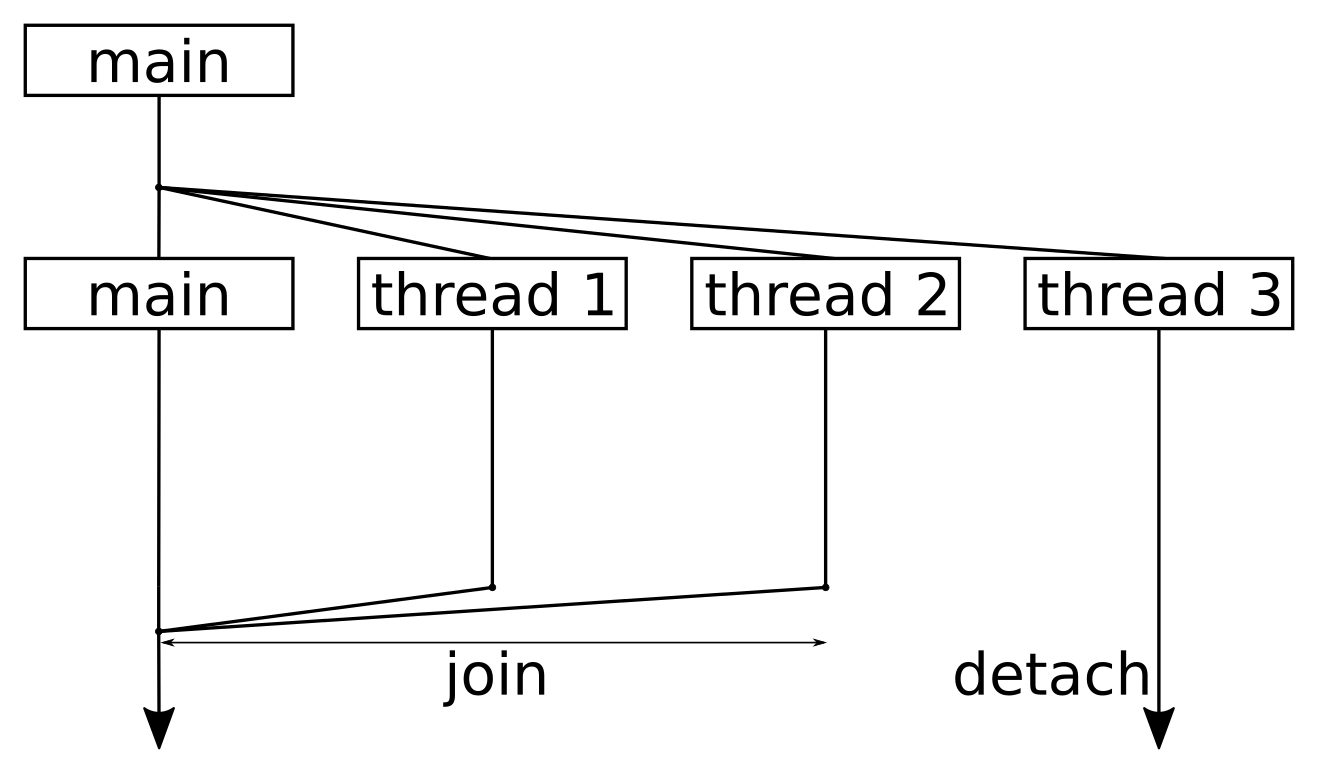

In the next module, you’ll see how multi-threaded programming can help you achieve concurrency in your applications. We start with a brief introduction to the fundamentals of multithreading and concurrency concepts. We then take an in-depth look at how these concepts work at the hardware-level as well as how both operating systems and frameworks use these low-level functions.

You will learn about the native multithreading and concurrency support available in C++ since the 2011 revision, synchronization and communication between threads, debugging concurrent C++ applications, and the best programming practices in C++.

Moving on, you’ll get an in-depth understanding of the C++ Standard Template Library. Where we show implementation-specific, problem-solution approach that will help you quickly overcome hurdles. You will learn the core STL concepts, such as containers, algorithms, utility classes, lambda expressions, iterators, and more while working on practical real-world recipes. These recipes will help you get the most from the STL and show you how to program in a better way.

This course is for intermediate to advanced level C++ developers who want to get the most out of C++ to build concurrent and scalable application.

Section 1, Mastering C++ Programming, introducing you to the latest features in C++ 17 and STL. It encourages clean code practices in C++ in general and demonstrates the GUI app-development options in C++. You’ll get tips on avoiding memory leaks using smart-pointers.

Section 2, Mastering C++ Multithreading, you’ll see how multi-threaded programming can help you achieve concurrency in your applications. We start with a brief introduction to the fundamentals of multithreading and concurrency concepts. We then take an in-depth look at how these concepts work at the hardware-level as well as how both operating systems and frameworks use these low-level functions. You will learn about the native multithreading and concurrency support available in C++ since the 2011 revision, synchronization and communication between threads, debugging concurrent C++ applications, and the best programming practices in C++.

Section 3, C++17 STL Cookbook, you’ll get an in-depth understanding of the C++ Standard Template Library; we show implementation-specific, problem-solution approaches that will help you quickly overcome hurdles. You will learn the core STL concepts, such as containers, algorithms, utility classes, lambda expressions, iterators, and more while working on practical real-world recipes. These recipes will help you get the most from the STL and show you how to program in a better way.

A strong understanding of C++ language is highly recommended as the book is for the experienced developers. You will need any OS (Windows, Linux, or macOS) and any C++ compiler installed on your systems in order to get started.

You can download the example code files for this learning path from your account at www.packtpub.com. If you purchased this learning path elsewhere, you can visit www.packtpub.com/support and register to have the files emailed directly to you.

You can download the code files by following these steps:

Once the file is downloaded, please make sure that you unzip or extract the folder using the latest version of:

The code bundle for the learning path is also hosted on GitHub at https://github.com/PacktPublishing/Expert-Cpp-Programming. We also have other code bundles from our rich catalog of books and videos available at https://github.com/PacktPublishing/. Check them out!

There are a number of text conventions used throughout this book.

CodeInText: Indicates code words in text, database table names, folder names, filenames, file extensions, pathnames, dummy URLs, user input, and Twitter handles. Here is an example: "Mount the downloaded WebStorm-10*.dmg disk image file as another disk in your system."

A block of code is set as follows:

html, body, #map {

height: 100%;

margin: 0;

padding: 0

}

When we wish to draw your attention to a particular part of a code block, the relevant lines or items are set in bold:

[default]

exten => s,1,Dial(Zap/1|30)

exten => s,2,Voicemail(u100)

exten => s,102,Voicemail(b100)

exten => i,1,Voicemail(s0)

Any command-line input or output is written as follows:

$ mkdir css

$ cd css

Bold: Indicates a new term, an important word, or words that you see onscreen. For example, words in menus or dialog boxes appear in the text like this. Here is an example: "Select System info from the Administration panel."

Feedback from our readers is always welcome.

General feedback: Email feedback@packtpub.com and mention the learning path title in the subject of your message. If you have questions about any aspect of this learning path, please email us at questions@packtpub.com.

Errata: Although we have taken every care to ensure the accuracy of our content, mistakes do happen. If you have found a mistake in this learning path, we would be grateful if you would report this to us. Please visit www.packtpub.com/submit-errata, selecting your learning path, clicking on the Errata Submission Form link, and entering the details.

Piracy: If you come across any illegal copies of our works in any form on the Internet, we would be grateful if you would provide us with the location address or website name. Please contact us at copyright@packtpub.com with a link to the material.

If you are interested in becoming an author: If there is a topic that you have expertise in and you are interested in either writing or contributing to a book, please visit authors.packtpub.com.

Please leave a review. Once you have read and used this learning path, why not leave a review on the site that you purchased it from? Potential readers can then see and use your unbiased opinion to make purchase decisions, we at Packt can understand what you think about our products, and our authors can see your feedback on their book. Thank you!

For more information about Packt, please visit packtpub.com.

As you know, the C++ language is the brain child of Bjarne Stroustrup, who developed C++ in 1979. The C++ programming language is standardized by International Organization for Standardization (ISO). The initial standardization was published in 1998, commonly referred to as C++98, and the next standardization C++03 was published in 2003, which was primarily a bug fix release with just one language feature for value initialization. In August 2011, the C++11 standard was published with several additions to the core language, including several significant interesting changes to the Standard Template Library (STL); C++11 basically replaced the C++03 standard. C++14 was published in December, 2014 with some new features, and later, the C++17 standard was published on July 31, 2017. At the time of writing this book, C++17 is the latest revision of the ISO/IEC standard for the C++ programming language.

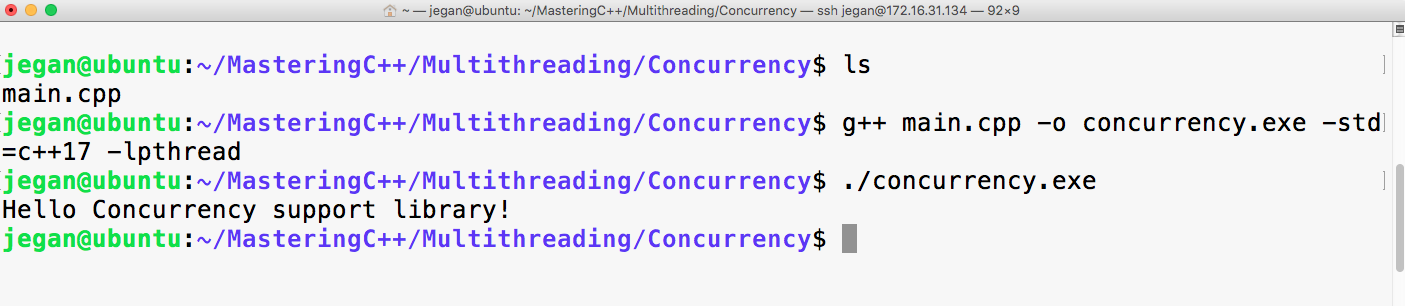

This chapter requires a compiler that supports C++17 features: gcc version 7 or later. As gcc version 7 is the latest version at the time of writing this book, I'll be using gcc version 7.1.0 in this chapter.

This chapter will cover the following topics:

Let's look into the STL topics one by one in the following sections.

The C++ Standard Template Library (STL) offers ready-made generic containers, algorithms that can be applied to the containers, and iterators to navigate the containers. The STL is implemented with C++ templates, and templates allow generic programming in C++.

The STL encourages a C++ developer to focus on the task at hand by freeing up the developer from writing low-level data structures and algorithms. The STL is a time-tested library that allows rapid application development.

The STL is an interesting piece of work and architecture. Its secret formula is compile-time polymorphism. To get better performance, the STL avoids dynamic polymorphism, saying goodbye to virtual functions. Broadly, the STL has the following four components:

The STL architecture stitches all the aforementioned four components together. It has many commonly used algorithms with performance guarantees. The interesting part about STL algorithms is that they work seamlessly without any knowledge about the containers that hold the data. This is made possible due to the iterators that offer high-level traversal APIs, which completely abstracts the underlying data structure used within a container. The STL makes use of operator overloading quite extensively. Let's understand the major components of STL one by one to get a good grasp of the STL conceptually.

The STL algorithms are powered by C++ templates; hence, the same algorithm works irrespective of what data type it deals with or independently of how the data is organized by a container. Interestingly, the STL algorithms are generic enough to support built-in and user-defined data types using templates. As a matter of fact, the algorithms interact with the containers via iterators. Hence, what matters to the algorithms is the iterator supported by the container. Having said that, the performance of an algorithm depends on the underlying data structure used within a container. Hence, certain algorithms work only on selective containers, as each algorithm supported by the STL expects a certain type of iterator.

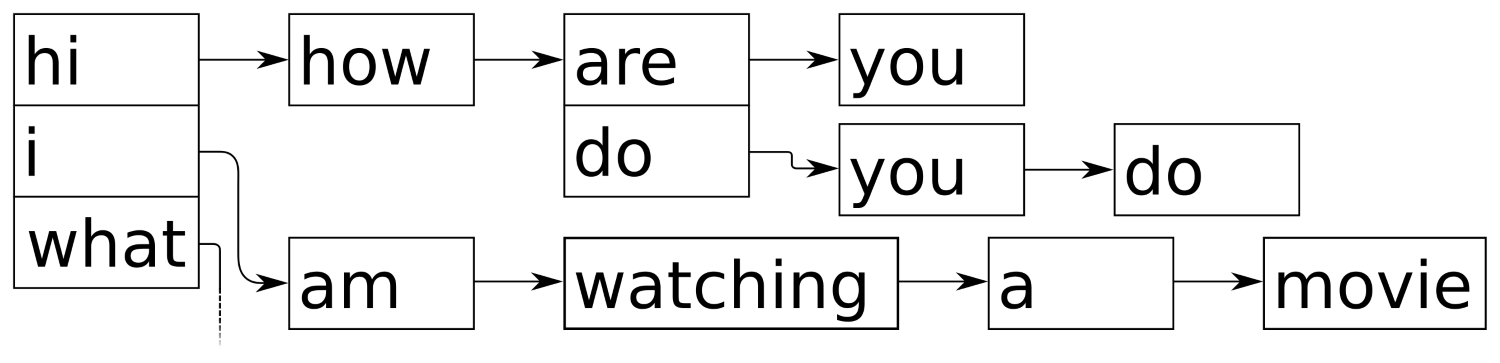

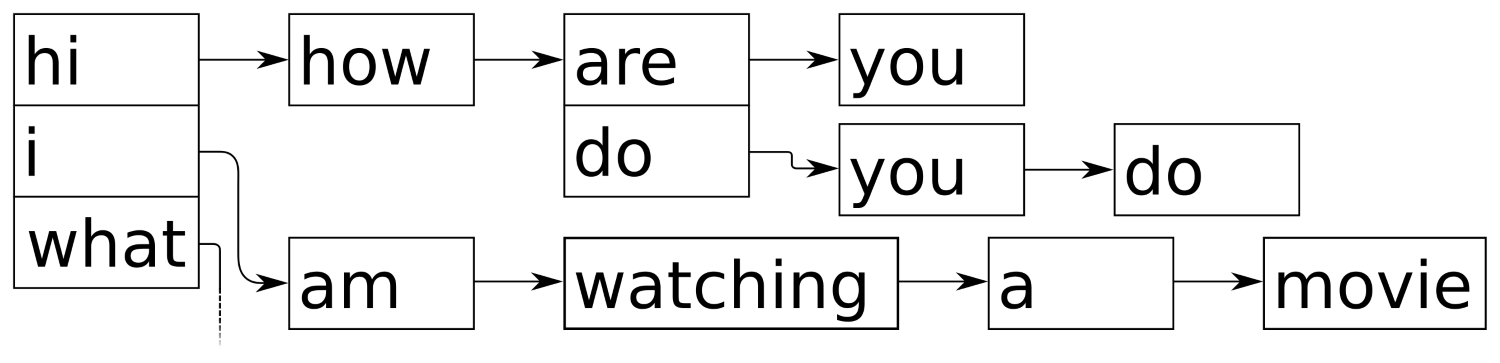

An iterator is a design pattern, but interestingly, the STL work started much before

Gang of Four published their design patterns-related work to the software community. Iterators themselves are objects that allow traversing the containers to access, modify, and manipulate the data stored in the containers. Iterators do this so magically that we don't realize or need to know where and how the data is stored and retrieved.

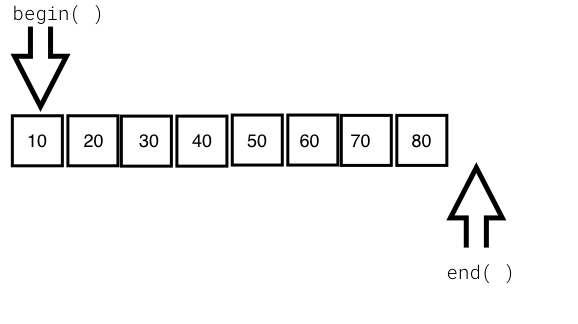

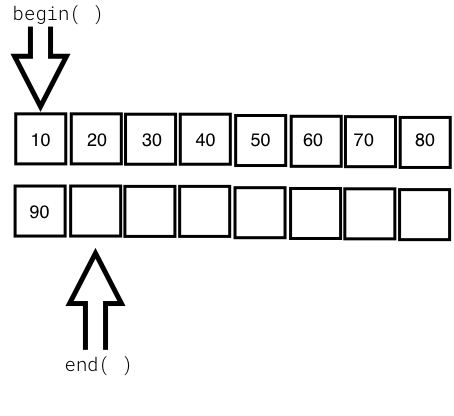

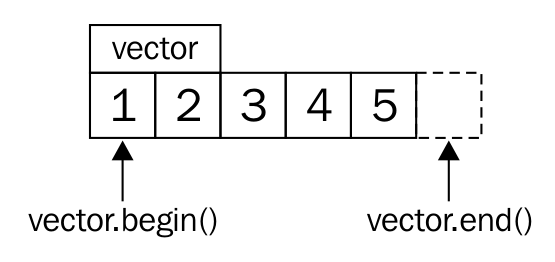

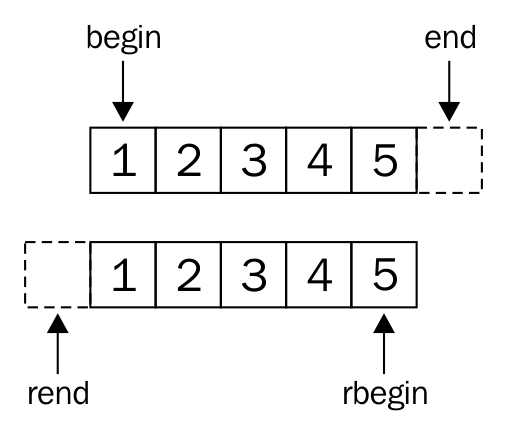

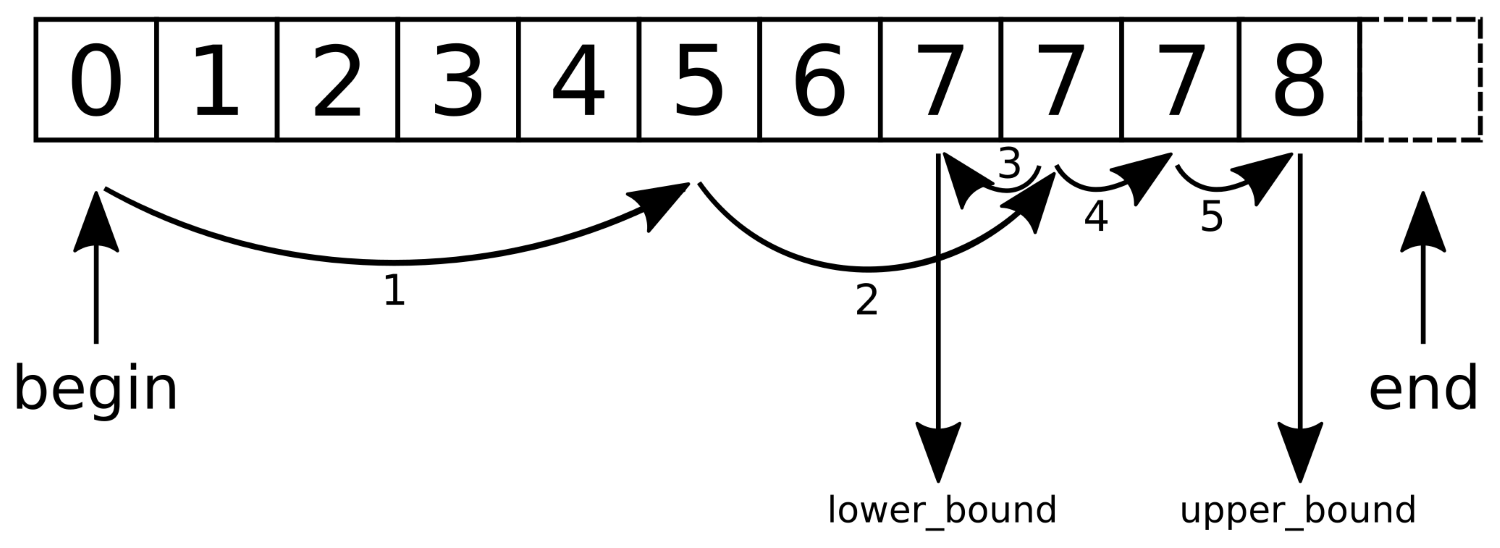

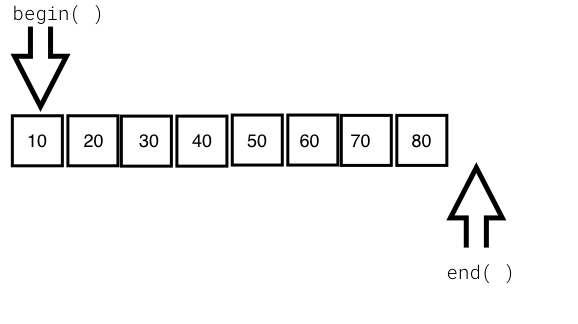

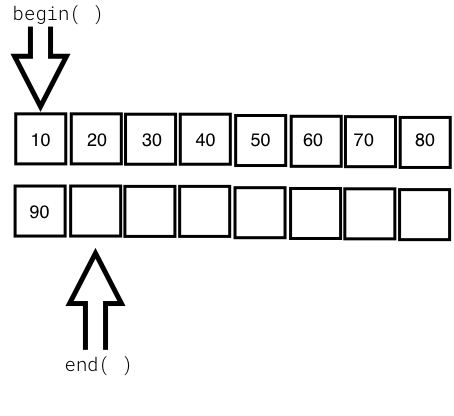

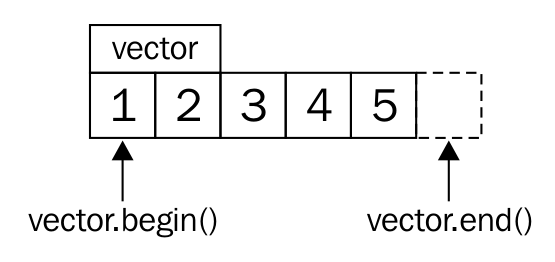

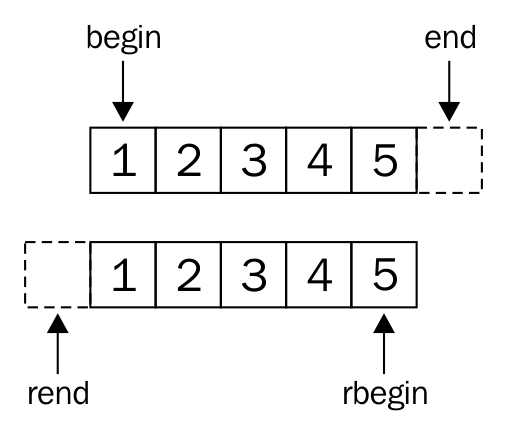

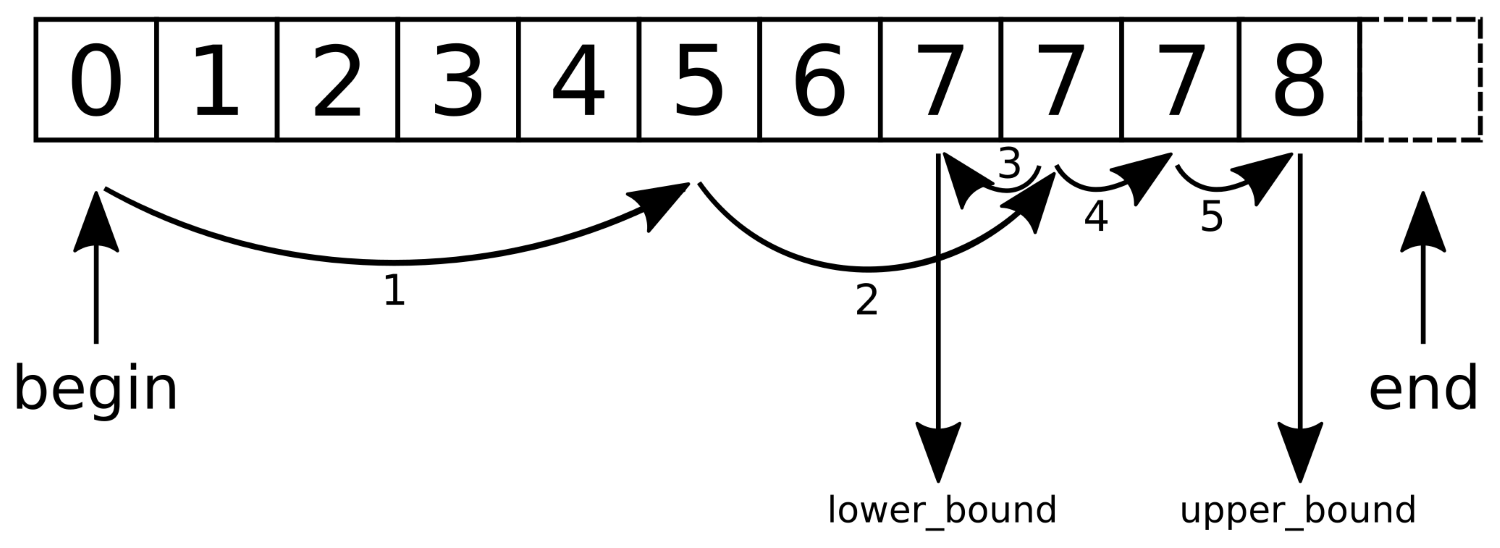

The following image visually represents an iterator:

From the preceding image, you can understand that every iterator supports the begin() API, which returns the first element position, and the end() API returns one position past the last element in the container.

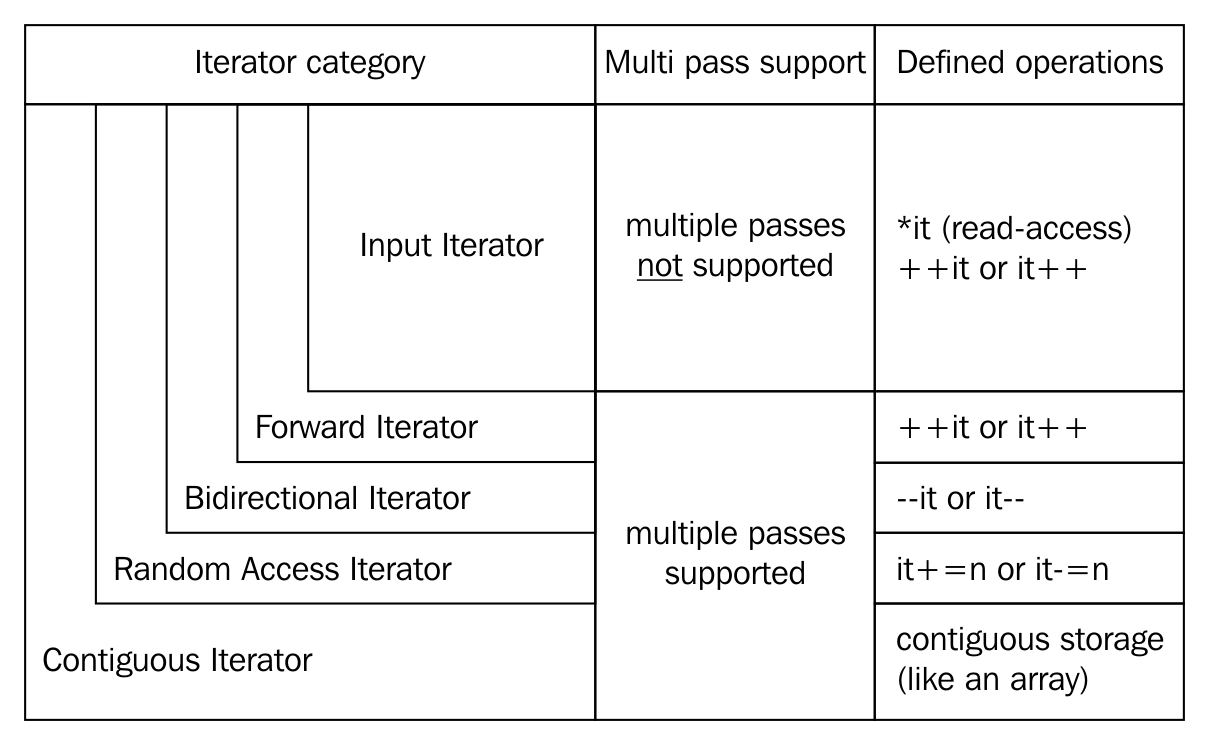

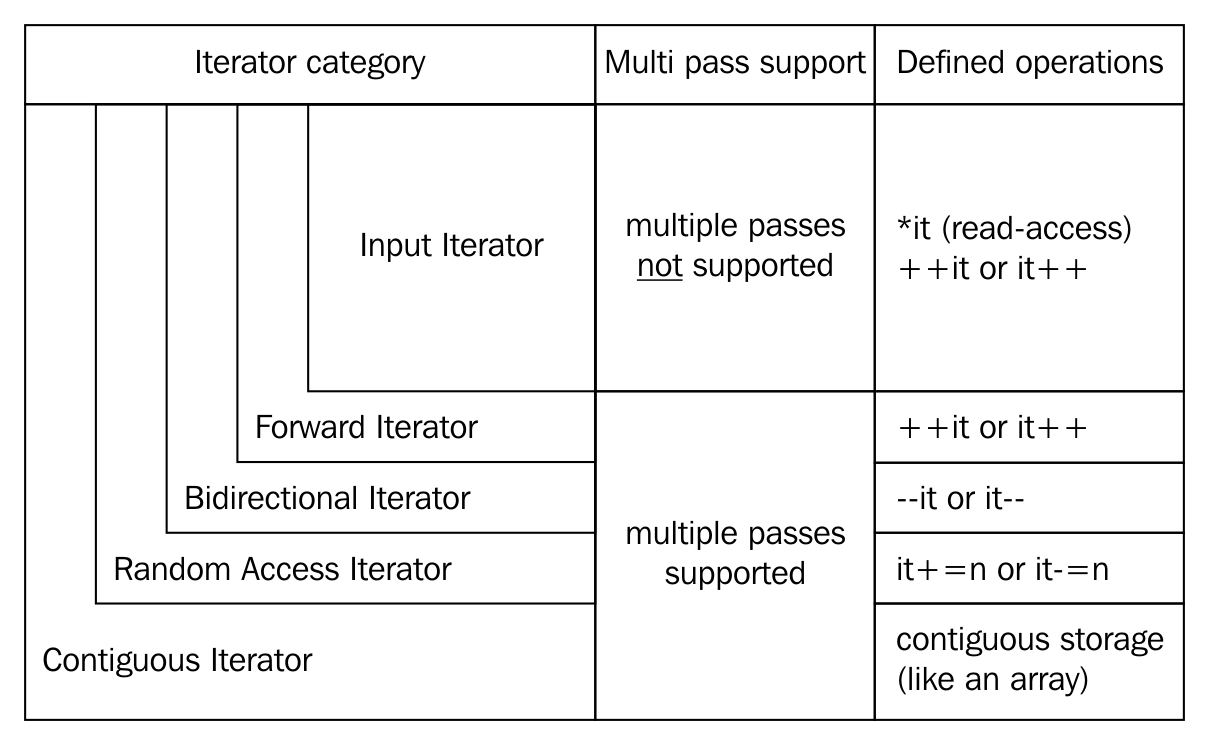

The STL broadly supports the following five types of iterators:

The container implements the iterator to let us easily retrieve and manipulate the data, without delving much into the technical details of a container.

The following table explains each of the five iterators:

|

The type of iterator |

Description |

|

Input iterator |

|

|

Output iterator |

|

|

Forward iterator |

|

|

Bidirectional iterator |

|

|

Random-access iterator |

|

STL containers are objects that typically grow and shrink dynamically. Containers use complex data structures to store the data under the hood and offer high-level functions to access the data without us delving into the complex internal implementation details of the data structure. STL containers are highly efficient and time-tested.

Every container uses different types of data structures to store, organize, and manipulate data in an efficient way. Though many containers may seem similar, they behave differently under the hood. Hence, the wrong choice of containers leads to application performance issues and unnecessary complexities.

Containers come in the following flavors:

The objects stored in the containers are copied or moved, and not referenced. We will explore every type of container in the upcoming sections with simple yet interesting examples.

Functors are objects that behave like regular functions. The beauty is that functors can be substituted in the place of function pointers. Functors are handy objects that let you extend or complement the behavior of an STL function without compromising the object-oriented coding principles.

Functors are easy to implement; all you need to do is overload the function operator. Functors are also referred to as functionoids.

The following code will demonstrate the way a simple functor can be implemented:

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <iterator>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

template <typename T>

class Printer {

public:

void operator() ( const T& element ) {

cout << element << "t";

}

};

int main () {

vector<int> v = { 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 };

cout << "nPrint the vector entries using Functor" << endl;

for_each ( v.begin(), v.end(), Printer<int>() );

cout << endl;

return 0;

}

Let's quickly compile the program using the following command:

g++ main.cpp -std=c++17

./a.out

Let's check the output of the program:

Print the vector entries using Functor

10 20 30 40 50

We hope you realize how easy and cool a functor is.

The STL supports quite an interesting variety of sequence containers. Sequence containers store homogeneous data types in a linear fashion, which can be accessed sequentially. The STL supports the following sequence containers:

As the objects stored in an STL container are nothing but copies of the values, the STL expects certain basic requirements from the user-defined data types in order to hold those objects inside a container. Every object stored in an STL container must provide the following as a minimum requirement:

Let's explore the sequence containers one by one in the following subsections.

The STL array container is a fixed-size sequence container, just like a C/C++ built-in array, except that the STL array is size-aware and a bit smarter than the built-in C/C++ array. Let's understand an STL array with an example:

#include <iostream>

#include <array>

using namespace std;

int main () {

array<int,5> a = { 1, 5, 2, 4, 3 };

cout << "nSize of array is " << a.size() << endl;

auto pos = a.begin();

cout << endl;

while ( pos != a.end() )

cout << *pos++ << "t";

cout << endl;

return 0;

}

The preceding code can be compiled and the output can be viewed with the following commands:

g++ main.cpp -std=c++17

./a.out

The output of the program is as follows:

Size of array is 5

1 5 2 4 3

The following line declares an array of a fixed size (5) and initializes the array with five elements:

array<int,5> a = { 1, 5, 2, 4, 3 };

The size mentioned can't be changed once declared, just like a C/C++ built-in array. The array::size() method returns the size of the array, irrespective of how many integers are initialized in the initializer list. The auto pos = a.begin() method declares an iterator of array<int,5> and assigns the starting position of the array. The array::end() method points to one position after the last element in the array. The iterator behaves like or mimics a C++ pointer, and dereferencing the iterator returns the value pointed by the iterator. The iterator position can be moved forward and backwards with ++pos and --pos, respectively.

The following table shows some commonly used array APIs:

|

API |

Description |

|

at( int index ) |

This returns the value stored at the position referred to by the index. The index is a zero-based index. This API will throw an std::out_of_range exception if the index is outside the index range of the array. |

|

operator [ int index ] |

This is an unsafe method, as it won't throw any exception if the index falls outside the valid range of the array. This tends to be slightly faster than at, as this API doesn't perform bounds checking. |

|

front() |

This returns the first element in the array. |

|

back() |

This returns the last element in the array. |

|

begin() |

This returns the position of the first element in the array |

|

end() |

This returns one position past the last element in the array |

|

rbegin() |

This returns the reverse beginning position, that is, it returns the position of the last element in the array |

|

rend() |

This returns the reverse end position, that is, it returns one position before the first element in the array |

|

size() |

This returns the size of the array |

The array container supports random access; hence, given an index, the array container can fetch a value with a runtime complexity of O(1) or constant time.

The array container elements can be accessed in a reverse fashion using the reverse iterator:

#include <iostream>

#include <array>

using namespace std;

int main () {

array<int, 6> a;

int size = a.size();

for (int index=0; index < size; ++index)

a[index] = (index+1) * 100;

cout << "nPrint values in original order ..." << endl;

auto pos = a.begin();

while ( pos != a.end() )

cout << *pos++ << "t";

cout << endl;

cout << "nPrint values in reverse order ..." << endl;

auto rpos = a.rbegin();

while ( rpos != a.rend() )

cout << *rpos++ << "t";

cout << endl;

return 0;

}

We will use the following command to get the output:

./a.out

The output is as follows:

Print values in original order ...

100 200 300 400 500 600

Print values in reverse order ...

600 500 400 300 200 100

Vector is a quite useful sequence container, and it works exactly as an array, except that the vector can grow and shrink at runtime while an array is of a fixed size. However, the data structure used under the hood in an array and vector is a plain simple built-in C/C++ style array.

Let's look at the following example to understand vectors better:

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

int main () {

vector<int> v = { 1, 5, 2, 4, 3 };

cout << "nSize of vector is " << v.size() << endl;

auto pos = v.begin();

cout << "nPrint vector elements before sorting" << endl;

while ( pos != v.end() )

cout << *pos++ << "t";

cout << endl;

sort( v.begin(), v.end() );

pos = v.begin();

cout << "nPrint vector elements after sorting" << endl;

while ( pos != v.end() )

cout << *pos++ << "t";

cout << endl;

return 0;

}

The preceding code can be compiled and the output can be viewed with the following commands:

g++ main.cpp -std=c++17

./a.out

The output of the program is as follows:

Size of vector is 5

Print vector elements before sorting

1 5 2 4 3

Print vector elements after sorting

1 2 3 4 5

The following line declares a vector and initializes the vector with five elements:

vector<int> v = { 1, 5, 2, 4, 3 };

However, a vector also allows appending values to the end of the vector by using the vector::push_back<data_type>( value ) API. The sort() algorithm takes two random access iterators that represent a range of data that must be sorted. As the vector internally uses a built-in C/C++ array, just like the STL array container, a vector also supports random access iterators; hence the sort() function is a highly efficient algorithm whose runtime complexity is logarithmic, that is, O(N log2 (N)).

The following table shows some commonly used vector APIs:

|

API |

Description |

|

at ( int index ) |

This returns the value stored at the indexed position. It throws the std::out_of_range exception if the index is invalid. |

|

operator [ int index ] |

This returns the value stored at the indexed position. It is faster than at( int index ), since no bounds checking is performed by this function. |

|

front() |

This returns the first value stored in the vector. |

|

back() |

This returns the last value stored in the vector. |

|

empty() |

This returns true if the vector is empty, and false otherwise. |

|

size() |

This returns the number of values stored in the vector. |

|

reserve( int size ) |

This reserves the initial size of the vector. When the vector size has reached its capacity, an attempt to insert new values requires vector resizing. This makes the insertion consume O(N) runtime complexity. The reserve() method is a workaround for the issue described. |

|

capacity() |

This returns the total capacity of the vector, while the size is the actual value stored in the vector. |

|

clear() |

This clears all the values. |

|

push_back<data_type>( value ) |

This adds a new value at the end of the vector. |

It would be really fun and convenient to read and print to/from the vector using istream_iterator and ostream_iterator. The following code demonstrates the use of a vector:

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <algorithm>

#include <iterator>

using namespace std;

int main () {

vector<int> v;

cout << "nType empty string to end the input once you are done feeding the vector" << endl;

cout << "nEnter some numbers to feed the vector ..." << endl;

istream_iterator<int> start_input(cin);

istream_iterator<int> end_input;

copy ( start_input, end_input, back_inserter( v ) );

cout << "nPrint the vector ..." << endl;

copy ( v.begin(), v.end(), ostream_iterator<int>(cout, "t") );

cout << endl;

return 0;

}

Basically, the copy algorithm accepts a range of iterators, where the first two arguments represent the source and the third argument represents the destination, which happens to be the vector:

istream_iterator<int> start_input(cin);

istream_iterator<int> end_input;

copy ( start_input, end_input, back_inserter( v ) );

The start_input iterator instance defines an istream_iterator iterator that receives input from istream and cin, and the end_input iterator instance defines an end-of-file delimiter, which is an empty string by default (""). Hence, the input can be terminated by typing "" in the command-line input terminal.

Similarly, let's understand the following code snippet:

cout << "nPrint the vector ..." << endl;

copy ( v.begin(), v.end(), ostream_iterator<int>(cout, "t") );

cout << endl;

The copy algorithm is used to copy the values from a vector, one element at a time, to ostream, separating the output with a tab character (t).

Every STL container has its own advantages and disadvantages. There is no single STL container that works better in all the scenarios. A vector internally uses an array data structure, and arrays are fixed in size in C/C++. Hence, when you attempt to add new values to the vector at the time the vector size has already reached its maximum capacity, then the vector will allocate new consecutive locations that can accommodate the old values and the new value in a contiguous location. It then starts copying the old values into the new locations. Once all the data elements are copied, the vector will invalidate the old location.

Whenever this happens, the vector insertion will take O(N) runtime complexity. As the size of the vector grows over time, on demand, the O(N) runtime complexity will show up a pretty bad performance. If you know the maximum size required, you could reserve so much initial size upfront in order to overcome this issue. However, not in all scenarios do you need to use a vector. Of course, a vector supports dynamic size and random access, which has performance benefits in some scenarios, but it is possible that the feature you are working on may not really need random access, in which case a list, deque, or some other container may work better for you.

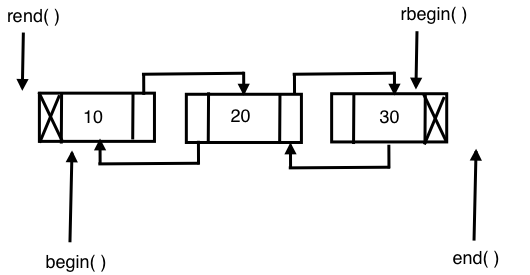

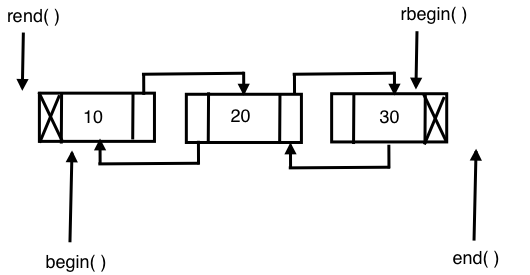

The list STL container makes use of a doubly linked list data structure internally. Hence, a list supports only sequential access, and searching a random value in a list in the worst case may take O(N) runtime complexity. However, if you know for sure that you only need sequential access, the list does offer its own benefits. The list STL container lets you insert data elements at the end, in the front, or in the middle with a constant time complexity, that is, O(1) runtime complexity in the best, average, and worst case scenarios.

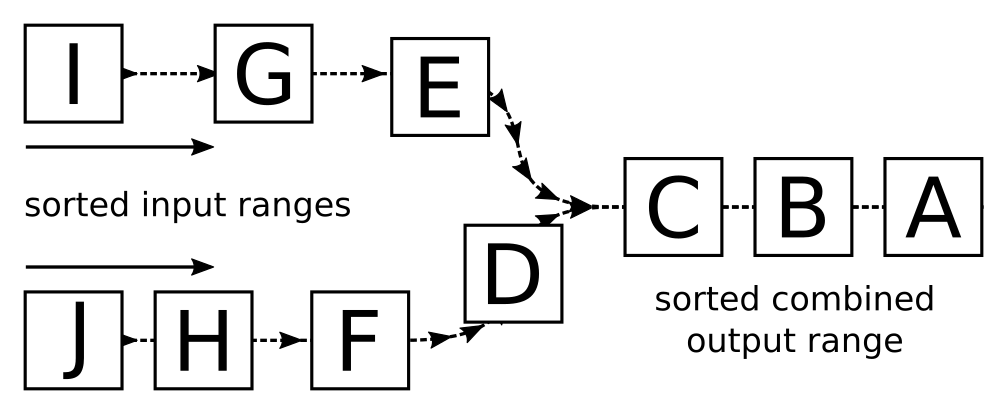

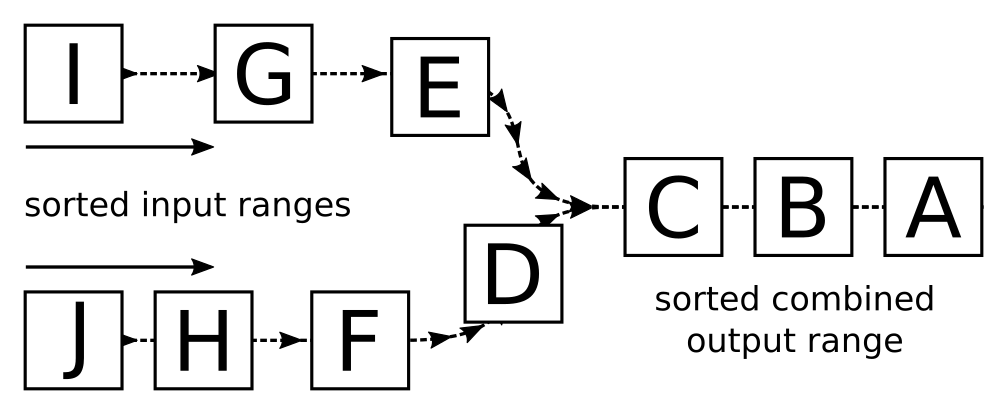

The following image demonstrates the internal data structure used by the list STL:

Let's write a simple program to get first-hand experience of using the list STL:

#include <iostream>

#include <list>

#include <iterator>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

int main () {

list<int> l;

for (int count=0; count<5; ++count)

l.push_back( (count+1) * 100 );

auto pos = l.begin();

cout << "nPrint the list ..." << endl;

while ( pos != l.end() )

cout << *pos++ << "-->";

cout << " X" << endl;

return 0;

}

I'm sure that by now you have got a taste of the C++ STL, its elegance, and its power. Isn't it cool to observe that the syntax remains the same for all the STL containers? You may have observed that the syntax remains the same no matter whether you are using an array, a vector, or a list. Trust me, you will get the same impression when you explore the other STL containers as well.

Having said that, the previous code is self-explanatory, as we did pretty much the same with the other containers.

Let's try to sort the list, as shown in the following code:

#include <iostream>

#include <list>

#include <iterator>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

int main () {

list<int> l = { 100, 20, 80, 50, 60, 5 };

auto pos = l.begin();

cout << "nPrint the list before sorting ..." << endl;

copy ( l.begin(), l.end(), ostream_iterator<int>( cout, "-->" ));

cout << "X" << endl;

l.sort();

cout << "nPrint the list after sorting ..." << endl;

copy ( l.begin(), l.end(), ostream_iterator<int>( cout, "-->" ));

cout << "X" << endl;

return 0;

}

Did you notice the sort() method? Yes, the list container has its own sorting algorithms. The reason for a list container to support its own version of a sorting algorithm is that the generic sort() algorithm expects a random access iterator, whereas a list container doesn't support random access. In such cases, the respective container will offer its own efficient algorithms to overcome the shortcoming.

Interestingly, the runtime complexity of the sort algorithm supported by a list is O (N log2 N).

The following table shows the most commonly used APIs of an STL list:

|

API |

Description |

|

front() |

This returns the first value stored in the list |

|

back() |

This returns the last value stored in the list |

|

size() |

This returns the count of values stored in the list |

|

empty() |

This returns true when the list is empty, and false otherwise |

|

clear() |

This clears all the values stored in the list |

|

push_back<data_type>( value ) |

This adds a value at the end of the list |

|

push_front<data_type>( value ) |

This adds a value at the front of the list |

|

merge( list ) |

This merges two sorted lists with values of the same type |

|

reverse() |

This reverses the list |

|

unique() |

This removes duplicate values from the list |

|

sort() |

This sorts the values stored in a list |

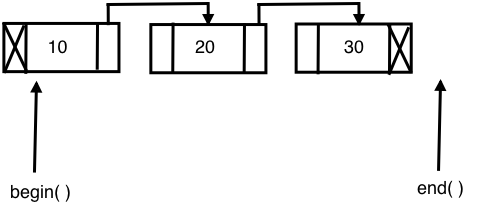

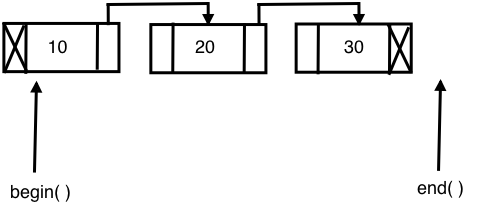

The STL's forward_list container is built on top of a singly linked list data structure; hence, it only supports navigation in the forward direction. As forward_list consumes one less pointer for every node in terms of memory and runtime, it is considered more efficient compared with the list container. However, as price for the extra edge of performance advantage, forward_list had to give up some functionalities.

The following diagram shows the internal data-structure used in forward_list:

Let's explore the following sample code:

#include <iostream>

#include <forward_list>

#include <iterator>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

int main ( ) {

forward_list<int> l = { 10, 10, 20, 30, 45, 45, 50 };

cout << "nlist with all values ..." << endl;

copy ( l.begin(), l.end(), ostream_iterator<int>(cout, "t") );

cout << "nSize of list with duplicates is " << distance( l.begin(), l.end() ) << endl;

l.unique();

cout << "nSize of list without duplicates is " << distance( l.begin(), l.end() ) << endl;

l.resize( distance( l.begin(), l.end() ) );

cout << "nlist after removing duplicates ..." << endl;

copy ( l.begin(), l.end(), ostream_iterator<int>(cout, "t") );

cout << endl;

return 0;

}

The output can be viewed with the following command:

./a.out

The output will be as follows:

list with all values ...

10 10 20 30 45 45 50

Size of list with duplicates is 7

Size of list without duplicates is 5

list after removing duplicates ...

10 20 30 45 50

The following code declares and initializes the forward_list container with some unique values and some duplicate values:

forward_list<int> l = { 10, 10, 20, 30, 45, 45, 50 };

As the forward_list container doesn't support the size() function, we used the distance() function to find the size of the list:

cout << "nSize of list with duplicates is " << distance( l.begin(), l.end() ) << endl;

The following forward_list<int>::unique() function removes the duplicate integers and retains only the unique values:

l.unique();

The following table shows the commonly used forward_list APIs:

|

API |

Description |

|

front() |

This returns the first value stored in the forward_list container |

|

empty() |

This returns true when the forward_list container is empty and false, otherwise |

|

clear() |

This clears all the values stored in forward_list |

|

push_front<data_type>( value ) |

This adds a value to the front of forward_list |

|

merge( list ) |

This merges two sorted forward_list containers with values of the same type |

|

reverse() |

This reverses the forward_list container |

|

unique() |

This removes duplicate values from the forward_list container |

|

sort() |

This sorts the values stored in forward_list |

Let's explore one more example to get a firm understanding of the forward_list container:

#include <iostream>

#include <forward_list>

#include <iterator>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

int main () {

forward_list<int> list1 = { 10, 20, 10, 45, 45, 50, 25 };

forward_list<int> list2 = { 20, 35, 27, 15, 100, 85, 12, 15 };

cout << "nFirst list before sorting ..." << endl;

copy ( list1.begin(), list1.end(), ostream_iterator<int>(cout, "t") );

cout << endl;

cout << "nSecond list before sorting ..." << endl;

copy ( list2.begin(), list2.end(), ostream_iterator<int>(cout, "t") );

cout << endl;

list1.sort();

list2.sort();

cout << "nFirst list after sorting ..." << endl;

copy ( list1.begin(), list1.end(), ostream_iterator<int>(cout, "t") );

cout << endl;

cout << "nSecond list after sorting ..." << endl;

copy ( list2.begin(), list2.end(), ostream_iterator<int>(cout, "t") );

cout << endl;

list1.merge ( list2 );

cout << "nMerged list ..." << endl;

copy ( list1.begin(), list1.end(), ostream_iterator<int>(cout, "t") );

cout << "nMerged list after removing duplicates ..." << endl;

list1.unique();

copy ( list1.begin(), list1.end(), ostream_iterator<int>(cout, "t") );

return 0;

}

The preceding code snippet is an interesting example that demonstrates the practical use of the sort(), merge(), and unique() STL algorithms.

The output can be viewed with the following command:

./a.out

The output of the program is as follows:

First list before sorting ...

10 20 10 45 45 50 25

Second list before sorting ...

20 35 27 15 100 85 12 15

First list after sorting ...

10 10 20 25 45 45 50

Second list after sorting ...

12 15 15 20 27 35 85 100

Merged list ...

10 10 12 15 15 20 20 25 27 35 45 45 50 85 100

Merged list after removing duplicates ...

10 12 15 20 25 27 35 45 50 85 100

The output and the program are pretty self-explanatory.

The deque container is a double-ended queue and the data structure used could be a dynamic array or a vector. In a deque, it is possible to insert an element both at the front and back, with a constant time complexity of O(1), unlike vectors, in which the time complexity of inserting an element at the back is O(1) while that for inserting an element at the front is O(N). The deque doesn't suffer from the problem of reallocation, which is suffered by a vector. However, all the benefits of a vector are there with deque, except that deque is slightly better in terms of performance as compared to a vector as there are several rows of dynamic arrays or vectors in each row.

The following diagram shows the internal data structure used in a deque container:

Let's write a simple program to try out the deque container:

#include <iostream>

#include <deque>

#include <algorithm>

#include <iterator>

using namespace std;

int main () {

deque<int> d = { 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 };

cout << "nInitial size of deque is " << d.size() << endl;

d.push_back( 60 );

d.push_front( 5 );

cout << "nSize of deque after push back and front is " << d.size() << endl;

copy ( d.begin(), d.end(), ostream_iterator<int>( cout, "t" ) );

d.clear();

cout << "nSize of deque after clearing all values is " << d.size() <<

endl;

cout << "nIs the deque empty after clearing values ? " << ( d.empty()

? "true" : "false" ) << endl;

return 0;

}

The output can be viewed with the following command:

./a.out

The output of the program is as follows:

Intitial size of deque is 5

Size of deque after push back and front is 7

Print the deque ...

5 10 20 30 40 50 60

Size of deque after clearing all values is 0

Is the deque empty after clearing values ? true

The following table shows the commonly used deque APIs:

|

API |

Description |

|

at ( int index ) |

This returns the value stored at the indexed position. It throws the std::out_of_range exception if the index is invalid. |

|

operator [ int index ] |

This returns the value stored at the indexed position. It is faster than at( int index ) since no bounds checking is performed by this function. |

|

front() |

This returns the first value stored in the deque. |

|

back() |

This returns the last value stored in the deque. |

|

empty() |

This returns true if the deque is empty and false, otherwise. |

|

size() |

This returns the number of values stored in the deque. |

|

capacity() |

This returns the total capacity of the deque, while size() returns the actual number of values stored in the deque. |

|

clear() |

This clears all the values. |

|

push_back<data_type>( value ) |

This adds a new value at the end of the deque. |

Associative containers store data in a sorted fashion, unlike the sequence containers. Hence, the order in which the data is inserted will not be retained by the associative containers. Associative containers are highly efficient in searching a value with O( log n ) runtime complexity. Every time a new value gets added to the container, the container will reorder the values stored internally if required.

The STL supports the following types of associative containers:

Associative containers organize the data as key-value pairs. The data will be sorted based on the key for random and faster access. Associative containers come in two flavors:

The following associative containers come under ordered containers, as they are ordered/sorted in a particular fashion. Ordered associative containers generally use some form of Binary Search Tree (BST); usually, a red-black tree is used to store the data:

The following associative containers come under unordered containers, as they are not ordered in any particular fashion and they use hash tables:

Let's understand the previously mentioned containers with examples in the following subsections.

A set container stores only unique values in a sorted fashion. A set organizes the values using the value as a key. The set container is immutable, that is, the values stored in a set can't be modified; however, the values can be deleted. A set generally uses a red-black tree data structure, which is a form of balanced BST. The time complexity of set operations are guaranteed to be O ( log N ).

Let's write a simple program using a set:

#include <iostream>

#include <set>

#include <vector>

#include <iterator>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

int main( ) {

set<int> s1 = { 1, 3, 5, 7, 9 };

set<int> s2 = { 2, 3, 7, 8, 10 };

vector<int> v( s1.size() + s2.size() );

cout << "nFirst set values are ..." << endl;

copy ( s1.begin(), s1.end(), ostream_iterator<int> ( cout, "t" ) );

cout << endl;

cout << "nSecond set values are ..." << endl;

copy ( s2.begin(), s2.end(), ostream_iterator<int> ( cout, "t" ) );

cout << endl;

auto pos = set_difference ( s1.begin(), s1.end(), s2.begin(), s2.end(), v.begin() );

v.resize ( pos - v.begin() );

cout << "nValues present in set one but not in set two are ..." << endl;

copy ( v.begin(), v.end(), ostream_iterator<int> ( cout, "t" ) );

cout << endl;

v.clear();

v.resize ( s1.size() + s2.size() );

pos = set_union ( s1.begin(), s1.end(), s2.begin(), s2.end(), v.begin() );

v.resize ( pos - v.begin() );

cout << "nMerged set values in vector are ..." << endl;

copy ( v.begin(), v.end(), ostream_iterator<int> ( cout, "t" ) );

cout << endl;

return 0;

}

The output can be viewed with the following command:

./a.out

The output of the program is as follows:

First set values are ...

1 3 5 7 9

Second set values are ...

2 3 7 8 10

Values present in set one but not in set two are ...

1 5 9

Merged values of first and second set are ...

1 2 3 5 7 8 9 10

The following code declares and initializes two sets, s1 and s2:

set<int> s1 = { 1, 3, 5, 7, 9 };

set<int> s2 = { 2, 3, 7, 8, 10 };

The following line will ensure that the vector has enough room to store the values in the resultant vector:

vector<int> v( s1.size() + s2.size() );

The following code will print the values in s1 and s2:

cout << "nFirst set values are ..." << endl;

copy ( s1.begin(), s1.end(), ostream_iterator<int> ( cout, "t" ) );

cout << endl;

cout << "nSecond set values are ..." << endl;

copy ( s2.begin(), s2.end(), ostream_iterator<int> ( cout, "t" ) );

cout << endl;

The set_difference() algorithm will populate the vector v with values only present in set s1 but not in s2. The iterator, pos, will point to the last element in the vector; hence, the vector resize will ensure that the extra spaces in the vector are removed:

auto pos = set_difference ( s1.begin(), s1.end(), s2.begin(), s2.end(), v.begin() );

v.resize ( pos - v.begin() );

The following code will print the values populated in the vector v:

cout << "nValues present in set one but not in set two are ..." << endl;

copy ( v.begin(), v.end(), ostream_iterator<int> ( cout, "t" ) );

cout << endl;

The set_union() algorithm will merge the contents of sets s1 and s2 into the vector, and the vector is then resized to fit only the merged values:

pos = set_union ( s1.begin(), s1.end(), s2.begin(), s2.end(), v.begin() );

v.resize ( pos - v.begin() );

The following code will print the merged values populated in the vector v:

cout << "nMerged values of first and second set are ..." << endl;

copy ( v.begin(), v.end(), ostream_iterator<int> ( cout, "t" ) );

cout << endl;

The following table describes the commonly used set APIs:

|

API |

Description |

|

insert( value ) |

This inserts a value into the set |

|

clear() |

This clears all the values in the set |

|

size() |

This returns the total number of entries present in the set |

|

empty() |

This will print true if the set is empty, and returns false otherwise |

|

find() |

This finds the element with the specified key and returns the iterator position |

|

equal_range() |

This returns the range of elements matching a specific key |

|

lower_bound() |

This returns an iterator to the first element not less than the given key |

|

upper_bound() |

This returns an iterator to the first element greater than the given key |

A map stores the values organized by keys. Unlike a set, a map has a dedicated key per value. Maps generally use a red-black tree as an internal data structure, which is a balanced BST that guarantees O( log N ) runtime efficiency for searching or locating a value in the map. The values stored in a map are sorted based on the key, using a red-black tree. The keys used in a map must be unique. A map will not retain the sequences of the input as it reorganizes the values based on the key, that is, the red-black tree will be rotated to balance the red-black tree height.

Let's write a simple program to understand map usage:

#include <iostream>

#include <map>

#include <iterator>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

int main ( ) {

map<string, long> contacts;

contacts["Jegan"] = 123456789;

contacts["Meena"] = 523456289;

contacts["Nitesh"] = 623856729;

contacts["Sriram"] = 993456789;

auto pos = contacts.find( "Sriram" );

if ( pos != contacts.end() )

cout << pos->second << endl;

return 0;

}

Let's compile and check the output of the program:

g++ main.cpp -std=c++17

./a.out

The output is as follows:

Mobile number of Sriram is 8901122334

The following line declares a map with a string name as the key and a long mobile number as the value stored in the map:

map< string, long > contacts;

The following code snippet adds four contacts organized by name as the key:

contacts[ "Jegan" ] = 1234567890;

contacts[ "Meena" ] = 5784433221;

contacts[ "Nitesh" ] = 4567891234;

contacts[ "Sriram" ] = 8901122334;

The following line will try to locate the contact with the name, Sriram, in the contacts map; if Sriram is found, then the find() function will return the iterator pointing to the location of the key-value pair; otherwise it returns the contacts.end() position:

auto pos = contacts.find( "Sriram" );

The following code verifies whether the iterator, pos, has reached contacts.end() and prints the contact number. Since the map is an associative container, it stores a key=>value pair; hence, pos->first indicates the key and pos->second indicates the value:

if ( pos != contacts.end() )

cout << "nMobile number of " << pos->first << " is " << pos->second << endl;

else

cout << "nContact not found." << endl;

The following table shows the commonly used map APIs:

|

API |

Description |

|

at ( key ) |

This returns the value for the corresponding key if the key is found; otherwise it throws the std::out_of_range exception |

|

operator[ key ] |

This updates an existing value for the corresponding key if the key is found; otherwise it will add a new entry with the respective key=>value supplied |

|

empty() |

This returns true if the map is empty, and false otherwise |

|

size() |

This returns the count of the key=>value pairs stored in the map |

|

clear() |

This clears the entries stored in the map |

|

count() |

This returns the number of elements matching the given key |

|

find() |

This finds the element with the specified key |

A multiset container works in a manner similar to a set container, except for the fact that a set allows only unique values to be stored whereas a multiset lets you store duplicate values. As you know, in the case of set and multiset containers, the values themselves are used as keys to organize the data. A multiset container is just like a set; it doesn't allow modifying the values stored in the multiset.

Let's write a simple program using a multiset:

#include <iostream>

#include <set>

#include <iterator>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

int main() {

multiset<int> s = { 10, 30, 10, 50, 70, 90 };

cout << "nMultiset values are ..." << endl;

copy ( s.begin(), s.end(), ostream_iterator<int> ( cout, "t" ) );

cout << endl;

return 0;

}

The output can be viewed with the following command:

./a.out

The output of the program is as follows:

Multiset values are ...

10 30 10 50 70 90

Interestingly, in the preceding output, you can see that the multiset holds duplicate values.

A multimap works exactly as a map, except that a multimap container will allow multiple values to be stored with the same key.

Let's explore the multimap container with a simple example:

#include <iostream>

#include <map>

#include <vector>

#include <iterator>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

int main() {

multimap< string, long > contacts = {

{ "Jegan", 2232342343 },

{ "Meena", 3243435343 },

{ "Nitesh", 6234324343 },

{ "Sriram", 8932443241 },

{ "Nitesh", 5534327346 }

};

auto pos = contacts.find ( "Nitesh" );

int count = contacts.count( "Nitesh" );

int index = 0;

while ( pos != contacts.end() ) {

cout << "\nMobile number of " << pos->first << " is " <<

pos->second << endl;

++index;

++pos;

if ( index == count )

break;

}

return 0;

}

The program can be compiled and the output can be viewed with the following commands:

g++ main.cpp -std=c++17

./a.out

The output of the program is as follows:

Mobile number of Nitesh is 6234324343

Mobile number of Nitesh is 5534327346

An unordered set works in a manner similar to a set, except that the internal behavior of these containers differs. A set makes use of red-black trees while an unordered set makes use of hash tables. The time complexity of set operations is O( log N) while the time complexity of unordered set operations is O(1); hence, the unordered set tends to be faster than the set.

The values stored in an unordered set are not organized in any particular fashion, unlike in a set, which stores values in a sorted fashion. If performance is the criteria, then an unordered set is a good bet; however, if iterating the values in a sorted fashion is a requirement, then set is a good choice.

An unordered map works in a manner similar to a map, except that the internal behavior of these containers differs. A map makes use of red-black trees while unordered map makes use of hash tables. The time complexity of map operations is O( log N) while that of unordered map operations is O(1); hence, an unordered map tends to be faster than a map.

The values stored in an unordered map are not organized in any particular fashion, unlike in a map where values are sorted by keys.

An unordered multiset works in a manner similar to a multiset, except that the internal behavior of these containers differs. A multiset makes use of red-black trees while an unordered multiset makes use of hash tables. The time complexity of multiset operations is O( log N) while that of unordered multiset operations is O(1). Hence, an unordered multiset tends to be faster than a multiset.

The values stored in an unordered multiset are not organized in any particular fashion, unlike in a multiset where values are stored in a sorted fashion. If performance is the criteria, unordered multisets are a good bet; however, if iterating the values in a sorted fashion is a requirement, then multiset is a good choice.

An unordered multimap works in a manner similar to a multimap, except that the internal behavior of these containers differs. A multimap makes use of red-black trees while an unordered multimap makes use of hash tables. The time complexity of multimap operations is O( log N) while that of unordered multimap operations is O(1); hence, an unordered multimap tends to be faster than a multimap.

The values stored in an unordered multimap are not organized in any particular fashion, unlike in multimaps where values are sorted by keys. If performance is the criteria, then an unordered multimap is a good bet; however, if iterating the values in a sorted fashion is a requirement, then multimap is a good choice.

Container adapters adapt existing containers to provide new containers. In simple terms, STL extension is done with composition instead of inheritance.

STL containers can't be extended by inheritance, as their constructors aren't virtual. Throughout the STL, you can observe that while static polymorphism is used both in terms of operator overloading and templates, dynamic polymorphism is consciously avoided for performance reasons. Hence, extending the STL by subclassing the existing containers isn't a good idea, as it would lead to memory leaks because container classes aren't designed to behave like base classes.

The STL supports the following container adapters:

Let's explore the container adapters in the following subsections.

Stack is not a new container; it is a template adapter class. The adapter containers wrap an existing container and provide high-level functionalities. The stack adapter container offers stack operations while hiding the unnecessary functionalities that are irrelevant for a stack. The STL stack makes use of a deque container by default; however, we can instruct the stack to use any existing container that meets the requirement of the stack during the stack instantiation.

Deques, lists, and vectors meet the requirements of a stack adapter.

A stack operates on the Last In First Out (LIFO) philosophy.

The following table shows commonly used stack APIs:

|

API |

Description |

|

top() |

This returns the top-most value in the stack, that is, the value that was added last |

|

push<data_type>( value ) |

This will push the value provided to the top of the stack |

|

pop() |

This will remove the top-most value from the stack |

|

size() |

This returns the number of values present in the stack |

|

empty() |

This returns true if the stack is empty; otherwise it returns false |

It's time to get our hands dirty; let's write a simple program to use a stack:

#include <iostream>

#include <stack>

#include <iterator>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

int main ( ) {

stack<string> spoken_languages;

spoken_languages.push ( "French" );

spoken_languages.push ( "German" );

spoken_languages.push ( "English" );

spoken_languages.push ( "Hindi" );

spoken_languages.push ( "Sanskrit" );

spoken_languages.push ( "Tamil" );

cout << "nValues in Stack are ..." << endl;

while ( ! spoken_languages.empty() ) {

cout << spoken_languages.top() << endl;

spoken_languages.pop();

}

cout << endl;

return 0;

}

The program can be compiled and the output can be viewed with the following command:

g++ main.cpp -std=c++17

./a.out

The output of the program is as follows:

Values in Stack are ...

Tamil

Kannada

Telugu

Sanskrit

Hindi

English

German

French

From the preceding output, we can see the LIFO behavior of stack.

A queue works based on the First In First Out (FIFO) principle. A queue is not a new container; it is a templatized adapter class that wraps an existing container and provides the high-level functionalities that are required for queue operations, while hiding the unnecessary functionalities that are irrelevant for a queue. The STL queue makes use of a deque container by default; however, we can instruct the queue to use any existing container that meets the requirement of the queue during the queue instantiation.

In a queue, new values can be added at the back and removed from the front. Deques, lists, and vectors meet the requirements of a queue adapter.

The following table shows the commonly used queue APIs:

|

API |

Description |

|

push() |

This appends a new value at the back of the queue |

|

pop() |

This removes the value at the front of the queue |

|

front() |

This returns the value in the front of the queue |

|

back() |

This returns the value at the back of the queue |

|

empty() |

This returns true when the queue is empty; otherwise it returns false |

|

size() |

This returns the number of values stored in the queue |

Let's use a queue in the following program:

#include <iostream>

#include <queue>

#include <iterator>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

int main () {

queue<int> q;

q.push ( 100 );

q.push ( 200 );

q.push ( 300 );

cout << "nValues in Queue are ..." << endl;

while ( ! q.empty() ) {

cout << q.front() << endl;

q.pop();

}

return 0;

}

The program can be compiled and the output can be viewed with the following commands:

g++ main.cpp -std=c++17

./a.out

The output of the program is as follows:

Values in Queue are ...

100

200

300

From the preceding output, you can observe that the values were popped out in the same sequence that they were pushed in, that is, FIFO.

A priority queue is not a new container; it is a templatized adapter class that wraps an existing container and provides high-level functionalities that are required for priority queue operations, while hiding the unnecessary functionalities that are irrelevant for a priority queue. A priority queue makes use of a vector container by default; however, a deque container also meets the requirement of the priority queue. Hence, during the priority queue instantiation, you could instruct the priority queue to make use of a deque as well.

A priority queue organizes the data in such a way that the highest priority value appears first; in other words, the values are sorted in a descending order.

The deque and vector meet the requirements of a priority queue adaptor.

The following table shows commonly used priority queue APIs:

|

API |

Description |

|

push() |

This appends a new value at the back of the priority queue |

|

pop() |

This removes the value at the front of the priority queue |

|

empty() |

This returns true when the priority queue is empty; otherwise it returns false |

|

size() |

This returns the number of values stored in the priority queue |

|

top() |

This returns the value in the front of the priority queue |

Let's write a simple program to understand priority_queue:

#include <iostream>

#include <queue>

#include <iterator>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

int main () {

priority_queue<int> q;

q.push( 100 );

q.push( 50 );

q.push( 1000 );

q.push( 800 );

q.push( 300 );

cout << "nSequence in which value are inserted are ..." << endl;

cout << "100t50t1000t800t300" << endl;

cout << "Priority queue values are ..." << endl;

while ( ! q.empty() ) {

cout << q.top() << "t";

q.pop();

}

cout << endl;

return 0;

}

The program can be compiled and the output can be viewed with the following command:

g++ main.cpp -std=c++17

./a.out

The output of the program is as follows:

Sequence in which value are inserted are ...

100 50 1000 800 300

Priority queue values are ...

1000 800 300 100 50

From the preceding output, you can observe that priority_queue is a special type of queue that reorders the inputs in such a way that the highest value appears first.

In this chapter you learned about ready-made generic containers, functors, iterators, and algorithms. You also learned set, map, multiset, and multimap associative containers, their internal data structures, and common algorithms that can be applied on them. Further you learned how to use the various containers with practical hands-on code samples.

In the next chapter, you will learn template programming, which helps you master the essentials of templates.

In this chapter, we will cover the following topics:

Let's now start learning generic programming.

Generic programming is a style of programming that helps you develop reusable code or generic algorithms that can be applied to a wide variety of data types. Whenever a generic algorithm is invoked, the data types will be supplied as parameters with a special syntax.

Let's say we would like to write a sort() function, which takes an array of inputs that needs to be sorted in an ascending order. Secondly, we need the sort() function to sort int, double, char, and string data types. There are a couple of ways this can be solved:

Well, both approaches have their own merits and demerits. The advantage of the first approach is that, since there are dedicated functions for the int, double, char, and string data types, the compiler will be able to perform type checking if an incorrect data type is supplied. The disadvantage of the first approach is that we have to write four different functions even though the logic remains the same across all the functions. If a bug is identified in the algorithm, it must be fixed separately in all four functions; hence, heavy maintenance efforts are required. If we need to support another data type, we will end up writing one more function, and this will keep growing as we need to support more data types.

The advantage of the second approach is that we could just write one macro for all the data types. However, one very discouraging disadvantage is that the compiler will not be able to perform type checking, and this approach is more prone to errors and may invite many unexpected troubles. This approach is dead against object-oriented coding principles.

C++ supports generic programming with templates, which has the following benefits:

However, the disadvantages are as follows:

A function template lets you parameterize a data type. The reason this is referred to as generic programming is that a single template function will support many built-in and user-defined data types. A templatized function works like a C-style macro, except for the fact that the C++ compiler will type check the function when we supply an incompatible data type at the time of invoking the template function.

It will be easier to understand the template concept with a simple example, as follows:

#include <iostream>

#include <algorithm>

#include <iterator>

using namespace std;

template <typename T, int size>

void sort ( T input[] ) {

for ( int i=0; i<size; ++i) {

for (int j=0; j<size; ++j) {

if ( input[i] < input[j] )

swap (input[i], input[j] );

}

}

}

int main () {

int a[10] = { 100, 10, 40, 20, 60, 80, 5, 50, 30, 25 };

cout << "nValues in the int array before sorting ..." << endl;

copy ( a, a+10, ostream_iterator<int>( cout, "t" ) );

cout << endl;

::sort<int, 10>( a );

cout << "nValues in the int array after sorting ..." << endl;

copy ( a, a+10, ostream_iterator<int>( cout, "t" ) );

cout << endl;

double b[5] = { 85.6d, 76.13d, 0.012d, 1.57d, 2.56d };

cout << "nValues in the double array before sorting ..." << endl;

copy ( b, b+5, ostream_iterator<double>( cout, "t" ) );

cout << endl;

::sort<double, 5>( b );

cout << "nValues in the double array after sorting ..." << endl;

copy ( b, b+5, ostream_iterator<double>( cout, "t" ) );

cout << endl;

string names[6] = {

"Rishi Kumar Sahay",

"Arun KR",

"Arun CR",

"Ninad",

"Pankaj",

"Nikita"

};

cout << "nNames before sorting ..." << endl;

copy ( names, names+6, ostream_iterator<string>( cout, "n" ) );

cout << endl;

::sort<string, 6>( names );

cout << "nNames after sorting ..." << endl;

copy ( names, names+6, ostream_iterator<string>( cout, "n" ) );

cout << endl;

return 0;

}

Run the following commands:

g++ main.cpp -std=c++17

./a.out

The output of the preceding program is as follows:

Values in the int array before sorting ...

100 10 40 20 60 80 5 50 30 25

Values in the int array after sorting ...

5 10 20 25 30 40 50 60 80 100

Values in the double array before sorting ...

85.6d 76.13d 0.012d 1.57d 2.56d

Values in the double array after sorting ...

0.012 1.57 2.56 76.13 85.6

Names before sorting ...

Rishi Kumar Sahay

Arun KR

Arun CR

Ninad

Pankaj

Nikita

Names after sorting ...

Arun CR

Arun KR

Nikita

Ninad

Pankaj

Rich Kumar Sahay

Isn't it really interesting to see just one template function doing all the magic? Yes, that's how cool C++ templates are!

The following code defines a function template. The keyword, template <typename T, int size>, tells the compiler that what follows is a function template:

template <typename T, int size>

void sort ( T input[] ) {

for ( int i=0; i<size; ++i) {

for (int j=0; j<size; ++j) {

if ( input[i] < input[j] )

swap (input[i], input[j] );

}

}

}

The line, void sort ( T input[] ), defines a function named sort, which returns void and receives an input array of type T. The T type doesn't indicate any specific data type. T will be deduced at the time of instantiating the function template during compile time.

The following code populates an integer array with some unsorted values and prints the same to the terminal:

int a[10] = { 100, 10, 40, 20, 60, 80, 5, 50, 30, 25 };

cout << "nValues in the int array before sorting ..." << endl;

copy ( a, a+10, ostream_iterator<int>( cout, "t" ) );

cout << endl;

The following line will instantiate an instance of a function template for the int data type. At this point, typename T is substituted and a specialized function is created for the int data type. The scope-resolution operator in front of sort, that is, ::sort(), ensures that it invokes our custom function, sort(), defined in the global namespace; otherwise, the C++ compiler will attempt to invoke the sort() algorithm defined in the std namespace, or from any other namespace if such a function exists. The <int, 10> variable tells the compiler to create an instance of a function, substituting typename T with int, and 10 indicates the size of the array used in the template function:

::sort<int, 10>( a );

The following lines will instantiate two additional instances that support a double array of 5 elements and a string array of 6 elements respectively:

::sort<double, 5>( b );

::sort<string, 6>( names );

If you are curious to know some more details about how the C++ compiler instantiates the function templates to support int, double, and string, you could try the Unix utilities, nm and c++filt. The nm Unix utility will list the symbols in the symbol table, as follows:

nm ./a.out | grep sort

00000000000017f1 W _Z4sortIdLi5EEvPT_

0000000000001651 W _Z4sortIiLi10EEvPT_

000000000000199b W _Z4sortINSt7__cxx1112basic_stringIcSt11char_traitsIcESaIcEEELi6EEvPT_

As you can see, there are three different overloaded sort functions in the binary; however, we have defined only one template function. As the C++ compiler has mangled names to deal with function overloading, it is difficult for us to interpret which function among the three functions is meant for the int, double, and string data types.

However, there is a clue: the first function is meant for double, the second is meant for int, and the third is meant for string. The name-mangled function has _Z4sortIdLi5EEvPT_ for double, _Z4sortIiLi10EEvPT_ for int, and _Z4sortINSt7__cxx1112basic_stringIcSt11char_traitsIcESaIcEEELi6EEvPT_ for string. There is another cool Unix utility to help you interpret the function signatures without much struggle. Check the following output of the c++filt utility:

c++filt _Z4sortIdLi5EEvPT_

void sort<double, 5>(double*)

c++filt _Z4sortIiLi10EEvPT_

void sort<int, 10>(int*)

c++filt _Z4sortINSt7__cxx1112basic_stringIcSt11char_traitsIcESaIcEEELi6EEvPT_

void sort<std::__cxx11::basic_string<char, std::char_traits<char>, std::allocator<char> >, 6>(std::__cxx11::basic_string<char, std::char_traits<char>, std::allocator<char> >*)

Hopefully, you will find these utilities useful while working with C++ templates. I'm sure these tools and techniques will help you to debug any C++ application.

Overloading function templates works exactly like regular function overloading in C++. However, I'll help you recollect the C++ function overloading basics.

The function overloading rules and expectations from the C++ compiler are as follows:

If any of these aforementioned rules aren't met, the C++ compiler will not treat them as overloaded functions. If there is any ambiguity in differentiating between the overloaded functions, the C++ compiler will report it promptly as a compilation error.

It is time to explore this with an example, as shown in the following program:

#include <iostream>

#include <array>

using namespace std;

void sort ( array<int,6> data ) {

cout << "Non-template sort function invoked ..." << endl;

int size = data.size();

for ( int i=0; i<size; ++i ) {

for ( int j=0; j<size; ++j ) {

if ( data[i] < data[j] )

swap ( data[i], data[j] );

}

}

}

template <typename T, int size>

void sort ( array<T, size> data ) {

cout << "Template sort function invoked with one argument..." << endl;

for ( int i=0; i<size; ++i ) {

for ( int j=0; j<size; ++j ) {

if ( data[i] < data[j] )

swap ( data[i], data[j] );

}

}

}

template <typename T>

void sort ( T data[], int size ) {

cout << "Template sort function invoked with two arguments..." << endl;

for ( int i=0; i<size; ++i ) {

for ( int j=0; j<size; ++j ) {

if ( data[i] < data[j] )

swap ( data[i], data[j] );

}

}

}

int main() {

//Will invoke the non-template sort function

array<int, 6> a = { 10, 50, 40, 30, 60, 20 };

::sort ( a );

//Will invoke the template function that takes a single argument

array<float,6> b = { 10.6f, 57.9f, 80.7f, 35.1f, 69.3f, 20.0f };

::sort<float,6>( b );

//Will invoke the template function that takes a single argument

array<double,6> c = { 10.6d, 57.9d, 80.7d, 35.1d, 69.3d, 20.0d };

::sort<double,6> ( c );

//Will invoke the template function that takes two arguments

double d[] = { 10.5d, 12.1d, 5.56d, 1.31d, 81.5d, 12.86d };

::sort<double> ( d, 6 );

return 0;

}

Run the following commands:

g++ main.cpp -std=c++17

./a.out

The output of the preceding program is as follows:

Non-template sort function invoked ...

Template sort function invoked with one argument...

Template sort function invoked with one argument...

Template sort function invoked with two arguments...

The following code is a non-template version of our custom sort() function:

void sort ( array<int,6> data ) {

cout << "Non-template sort function invoked ..." << endl;

int size = data.size();

for ( int i=0; i<size; ++i ) {

for ( int j=0; j<size; ++j ) {

if ( data[i] < data[j] )

swap ( data[i], data[j] );

}

}

}

Non-template functions and template functions can coexist and participate in function overloading. One weird behavior of the preceding function is that the size of the array is hardcoded.

The second version of our sort() function is a template function, as shown in the following code snippet. Interestingly, the weird issue that we noticed in the first non-template sort() version is addressed here:

template <typename T, int size>

void sort ( array<T, size> data ) {

cout << "Template sort function invoked with one argument..." << endl;

for ( int i=0; i<size; ++i ) {

for ( int j=0; j<size; ++j ) {

if ( data[i] < data[j] )

swap ( data[i], data[j] );

}

}

}

In the preceding code, both the data type and the size of the array are passed as template arguments, which are then passed to the function call arguments. This approach makes the function generic, as this function can be instantiated for any data type.

The third version of our custom sort() function is also a template function, as shown in the following code snippet:

template <typename T>

void sort ( T data[], int size ) {

cout << "Template sort function invoked with two argument..." << endl;

for ( int i=0; i<size; ++i ) {

for ( int j=0; j<size; ++j ) {

if ( data[i] < data[j] )

swap ( data[i], data[j] );

}

}

}

The preceding template function takes a C-style array; hence, it also expects the user to indicate its size. However, the size of the array could be computed within the function, but for demonstration purposes, I need a function that takes two arguments. The previous function isn't recommended, as it uses a C-style array; ideally, we would use one of the STL containers.

Now, let's understand the main function code. The following code declares and initializes the STL array container with six values, which is then passed to our sort() function defined in the default namespace:

//Will invoke the non-template sort function

array<int, 6> a = { 10, 50, 40, 30, 60, 20 };

::sort ( a );

The preceding code will invoke the non-template sort() function. An important point to note is that, whenever C++ encounters a function call, it first looks for a non-template version; if C++ finds a matching non-template function version, its search for the correct function definition ends there. If the C++ compiler isn't able to identify a non-template function definition that matches the function call signature, then it starts looking for any template function that could support the function call and instantiates a specialized function for the data type required.

Let's understand the following code:

//Will invoke the template function that takes a single argument

array<float,6> b = { 10.6f, 57.9f, 80.7f, 35.1f, 69.3f, 20.0f };

::sort<float,6>( b );

This will invoke the template function that receives a single argument. As there is no non-template sort() function that receives an array<float,6> data type, the C++ compiler will instantiate such a function out of our user-defined sort() template function with a single argument that takes array<float, 6>.

In the same way, the following code triggers the compiler to instantiate a double version of the template sort() function that receives array<double, 6>:

//Will invoke the template function that takes a single argument

array<double,6> c = { 10.6d, 57.9d, 80.7d, 35.1d, 69.3d, 20.0d };

::sort<double,6> ( c );

Finally, the following code will instantiate an instance of the template sort() that receives two arguments and invokes the function:

//Will invoke the template function that takes two arguments

double d[] = { 10.5d, 12.1d, 5.56d, 1.31d, 81.5d, 12.86d };

::sort<double> ( d, 6 );

If you have come this far, I'm sure you like the C++ template topics discussed so far.

C++ templates extend the function template concepts to classes too, and enable us to write object-oriented generic code. In the previous sections, you learned the use of function templates and overloading. In this section, you will learn writing template classes that open up more interesting generic programming concepts.

A class template lets you parameterize the data type on the class level via a template type expression.

Let's understand a class template with the following example:

//myalgorithm.h

#include <iostream>

#include <algorithm>

#include <array>

#include <iterator>

using namespace std;

template <typename T, int size>

class MyAlgorithm {

public:

MyAlgorithm() { }

~MyAlgorithm() { }

void sort( array<T, size> &data ) {

for ( int i=0; i<size; ++i ) {

for ( int j=0; j<size; ++j ) {

if ( data[i] < data[j] )

swap ( data[i], data[j] );

}

}

}

void sort ( T data[size] );

};

template <typename T, int size>

inline void MyAlgorithm<T, size>::sort ( T data[size] ) {

for ( int i=0; i<size; ++i ) {

for ( int j=0; j<size; ++j ) {

if ( data[i] < data[j] )

swap ( data[i], data[j] );

}

}

}

Let's use myalgorithm.h in the following main.cpp program as follows:

#include "myalgorithm.h"

int main() {

MyAlgorithm<int, 10> algorithm1;

array<int, 10> a = { 10, 5, 15, 20, 25, 18, 1, 100, 90, 18 };

cout << "nArray values before sorting ..." << endl;

copy ( a.begin(), a.end(), ostream_iterator<int>(cout, "t") );

cout << endl;

algorithm1.sort ( a );

cout << "nArray values after sorting ..." << endl;

copy ( a.begin(), a.end(), ostream_iterator<int>(cout, "t") );

cout << endl;

MyAlgorithm<int, 10> algorithm2;

double d[] = { 100.0, 20.5, 200.5, 300.8, 186.78, 1.1 };

cout << "nArray values before sorting ..." << endl;

copy ( d.begin(), d.end(), ostream_iterator<double>(cout, "t") );

cout << endl;

algorithm2.sort ( d );

cout << "nArray values after sorting ..." << endl;

copy ( d.begin(), d.end(), ostream_iterator<double>(cout, "t") );

cout << endl;

return 0;

}