In this section, we are going to implement a program that prints to the terminal concurrently from many threads. In order to prevent garbling of the messages due to concurrency, we implement a little helper class that synchronizes printing between threads:

- As always, the includes come first:

#include <iostream>

#include <thread>

#include <mutex>

#include <sstream>

#include <vector>

using namespace std;

- Then we implement our helper class, which we call pcout. The p stands for parallel because it works in a synchronized way for parallel contexts. The idea is that pcout publicly inherits from stringstream. This way we can use operator<< on instances of it. As soon as a pcout instance is destroyed, its destructor locks a mutex and then prints the content of the stringstream buffer. We will see how to use it in the next step:

struct pcout : public stringstream {

static inline mutex cout_mutex;

~pcout() {

lock_guard<mutex> l {cout_mutex};

cout << rdbuf();

cout.flush();

}

};

- Now let's write two functions that can be executed by additional threads. Both accept a thread ID as arguments. Then, their only difference is that the first one simply uses cout for printing. The other one looks nearly identical, but instead of using cout directly, it instantiates pcout. This instance is a temporary object that lives only exactly for this line of code. After all operator<< calls have been executed, the internal string stream is filled with what we want to print. Then pcout instance's destructor is called. We have seen what the destructor does: it locks a specific mutex all pcout instances share along and prints:

static void print_cout(int id)

{

cout << "cout hello from " << id << 'n';

}

static void print_pcout(int id)

{

pcout{} << "pcout hello from " << id << 'n';

}

- Let's try it out. First, we are going to use print_cout, which just uses cout for printing. We start 10 threads which concurrently print their strings and wait until they finish:

int main()

{

vector<thread> v;

for (size_t i {0}; i < 10; ++i) {

v.emplace_back(print_cout, i);

}

for (auto &t : v) { t.join(); }

- Then we do the same thing with the print_pcout function:

cout << "=====================n";

v.clear();

for (size_t i {0}; i < 10; ++i) {

v.emplace_back(print_pcout, i);

}

for (auto &t : v) { t.join(); }

}

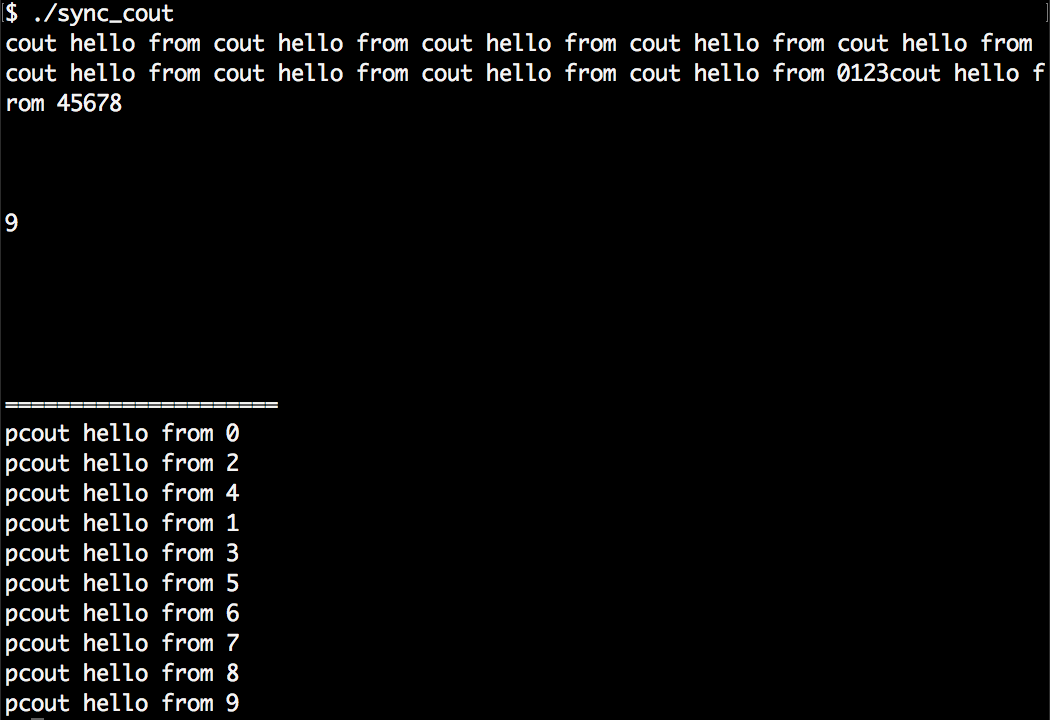

- Compiling and running the program yields the following result. As we see, the first 10 prints are completely garbled. This is how it can look like when cout is used concurrently without locking. The last 10 lines of the program are the print_pcout lines which do not show any signs of garbling. We can see that they are printed from different threads because their order appears randomized every time when we run the program again: