The zip function accepts two tuples, but looks horribly complicated, although it has a very crisp implementation:

template <typename T1, typename T2>

auto zip(const T1 &a, const T2 &b)

{

auto z ([](auto ...xs) {

return [xs...](auto ...ys) {

return tuple_cat(make_tuple(xs, ys) ...);

};

});

return apply(apply(z, a), b);

}

In order to understand this code better, imagine for a moment that the tuple a carries the values, 1, 2, 3, and tuple b carries the values, 'a', 'b', 'c'.

In such a case, calling apply(z, a) leads to a function call z(1, 2, 3), which returns another function object that captures those values, 1, 2, 3, in the parameter pack xs. When this function object is then called with apply(z(1, 2, 3), b), it gets the values, 'a', 'b', 'c', stuffed into the parameter pack, ys. This is basically the same as if we called z(1, 2, 3)('a', 'b', 'c') directly.

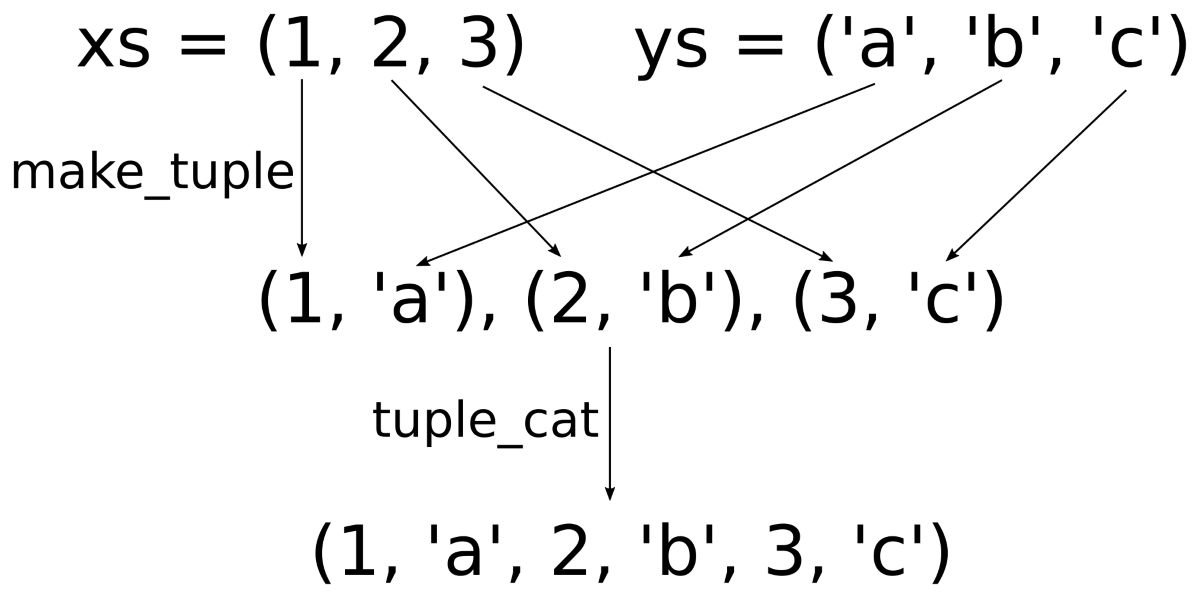

Okay, now that we have xs = (1, 2, 3) and ys = ('a', 'b', 'c'), what happens then? The expression tuple_cat(make_tuple(xs, ys) ...) does the following magic; have a look at the diagram:

At first, the items from xs and ys are zipped together by interleaving them pairwise. This "pairwise interleaving" happens in the make_tuple(xs, ys) ... expression. This initially only leads to a variadic list of tuples with two items each. In order to get one large tuple, we apply tuple_cat on them and then we finally get a large concatenated tuple that contains all the members of the initial tuples in an interleaved manner.