Weak pointers provide us a way to point at an object maintained by shared pointers without incrementing its use counter. Okay, a raw pointer could do the same, but a raw pointer cannot tell us if it is dangling or not. A weak pointer can!

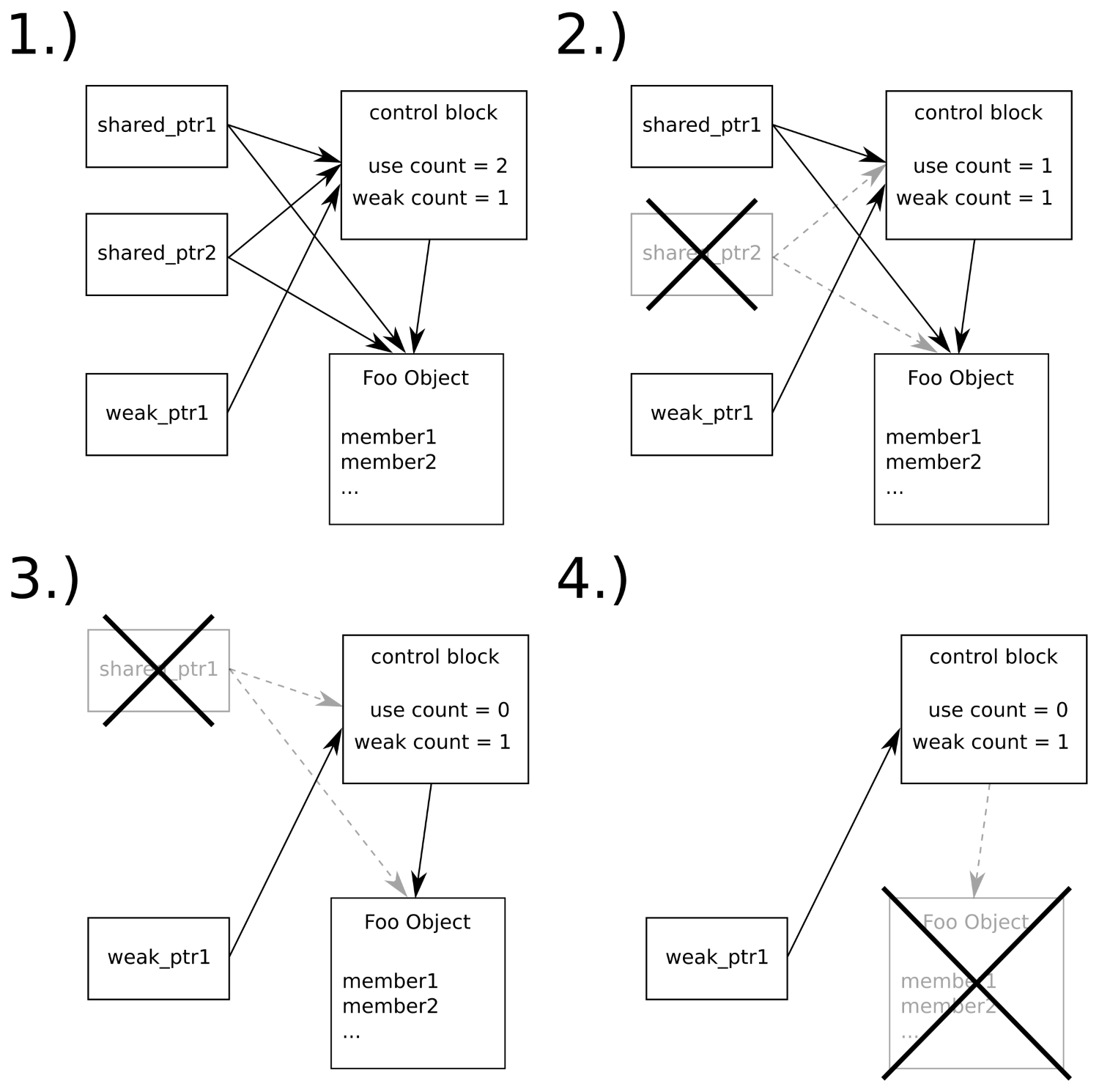

In order to understand how weak pointers as an addition to shared pointers work, let's directly jump to an illustrating diagram:

The flow is similar to the diagram in the recipe about shared pointers. In step 1, we have two shared pointers and a weak pointer pointing to the object of type Foo. Although there are three objects pointing to it, only the shared pointers manipulate its use counter, which is why it has the value 2. The weak pointer only manipulates a weak counter of the control block. In steps 2 and 3, the shared pointer instances are destroyed, which leads stepwise to a use counter of 0. In step 4, this results in the Foo object being deleted, but the control block stays there. The weak pointer still needs the control block in order to distinguish if it dangles or not. Only when the last weak pointer that still points to a control block also goes out of scope, the control block is deleted.

We can also say that a dangling weak pointer has expired. In order to check for this attribute, we can ask weak_ptr pointer's expired method, which returns a boolean value. If it is true, then we cannot dereference the weak pointer because there is no object to dereference any longer.

In order to dereference a weak pointer, we need to call lock(). This is safe and convenient because this function returns us a shared pointer. As long as we hold this shared pointer, the object behind it cannot vanish because we incremented the use counter by locking it. If the object is deleted, shortly before the lock() call, then the shared pointer it returns is effectively a null pointer.