A plain serial version of this program without any async and future magic would look like the following:

int main()

{

string result {

concat(

twice(

concat(

create("foo "),

create("bar "))),

concat(

create("this "),

create("that "))) };

cout << result << 'n';

}

In this recipe, we wrote the helper functions async_adapter and asynchronize that helped us create new functions from create, concat, and twice. We called those new asynchronous functions pcreate, pconcat, and ptwice.

Let us first ignore the complexity of the implementation of async_adapter and asynchronize, in order to first have a look what this got us.

The serial version looks similar to this code:

string result {concat( ... )};

cout << result << 'n';

The parallelized version looks similar to the following:

auto result (pconcat( ... ));

cout << result().get() << 'n';

Okay, now we get at the complicated part. The type of the parallelized result is not string, but a callable object that returns a future<string> on which we can call get(). This might indeed look crazy at first.

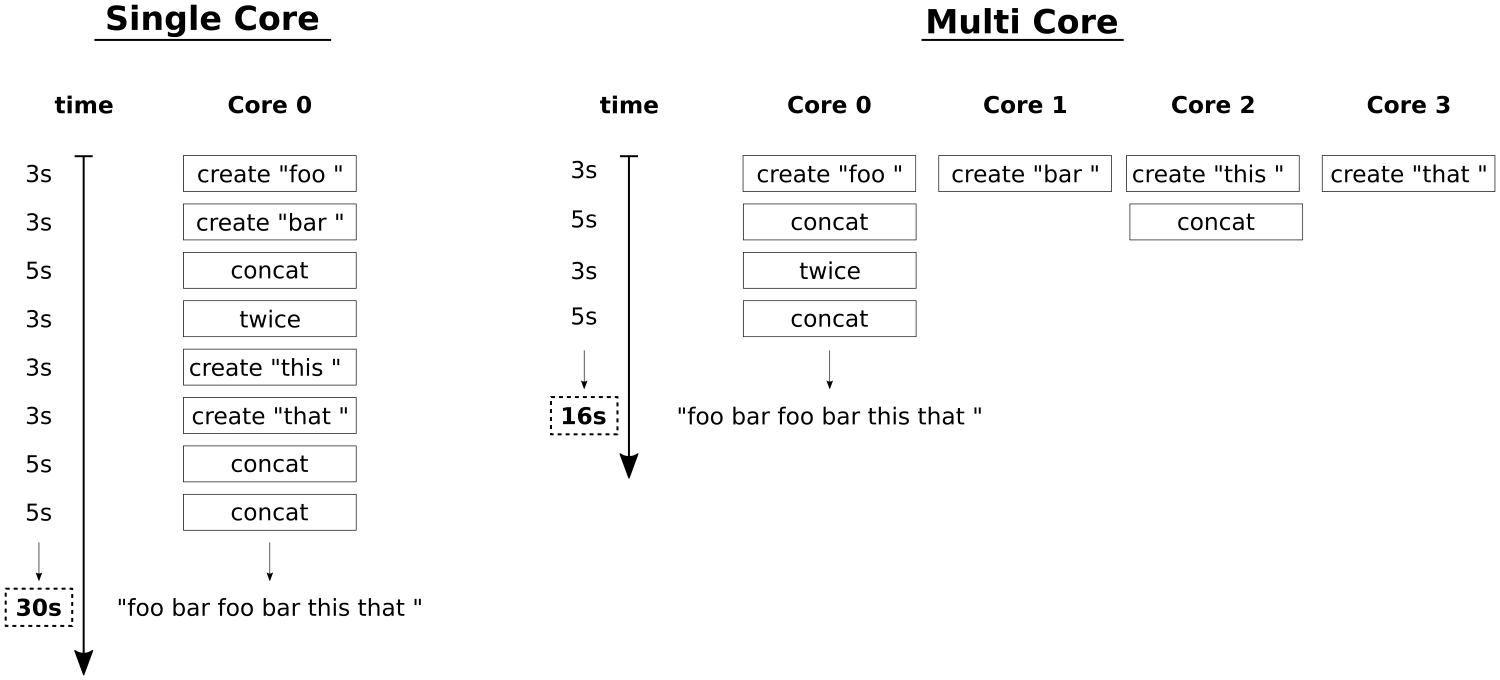

So, how and why did we exactly end up with callable objects that return futures? The problem with our create, concat, and twice methods is, that they are slow. (okay, we made them artificially slow, because we tried to model real life tasks that consume a lot of CPU time). But we identified that the dependency tree which describes the data flow has independent parts that could be executed in parallel. Let's have a look at two example schedules:

On the left side, we see a single core schedule. All the function calls have to be done one after each other because we have only a single CPU. That means, that when create costs 3 seconds, concat costs 5 seconds and twice costs 3 seconds, it will take 30 seconds to get the end result.

On the right side, we see a parallel schedule where as much is done in parallel as the dependencies between the function calls allow. In an ideal world with four cores, we can create all substrings at the same time, then concatenate them and so on. The minimal time to get the result with an optimal parallel schedule is 16 seconds. We cannot go faster if we cannot make the function calls themselves faster. With just four CPU cores we can achieve this execution time. We measurably achieved the optimal schedule. How did it work?

We could naively write the following code:

auto a (async(launch::async, create, "foo "));

auto b (async(launch::async, create, "bar "));

auto c (async(launch::async, create, "this "));

auto d (async(launch::async, create, "that "));

auto e (async(launch::async, concat, a.get(), b.get()));

auto f (async(launch::async, concat, c.get(), d.get()));

auto g (async(launch::async, twice, e.get()));

auto h (async(launch::async, concat, g.get(), f.get()));

This is a good start for a, b, c, and d, which represent the four substrings to begin with. These are created asynchronously in the background. Unfortunately, this code blocks on the line where we initialize e. In order to concatenate a and b, we need to call get() on both of them, which blocks until these values are ready. Obviously, this is not a good idea, because the parallelization stops being parallel on the first get() call. We need a better strategy.

Okay, so let us roll out the complicated helper functions we wrote. The first one is asynchronize:

template <typename F>

static auto asynchronize(F f)

{

return [f](auto ... xs) {

return [=] () {

return async(launch::async, f, xs...);

};

};

}

When we have a function int f(int, int) then we can do the following:

auto f2 ( asynchronize(f) );

auto f3 ( f2(1, 2) );

auto f4 ( f3() );

int result { f4.get() };

f2 is our asynchronous version of f. It can be called with the same arguments like f, because it mimics f. Then it returns a callable object, which we save in f3. f3 now captures f and the arguments 1, 2, but it did not call anything yet. This is just about the capturing.

When we call f3() now, then we finally get a future, because f3() does the async(launch::async, f, 1, 2); call! In that sense, the semantic meaning of f3 is "Take the captured function and the arguments, and throw them together into std::async.".

The inner lambda expression that does not accept any arguments gives us an indirection. With it, we can set up work for parallel dispatch but do not have to call anything that blocks, yet. We follow the same principle in the much more complicated function async_adapter:

template <typename F>

static auto async_adapter(F f)

{

return [f](auto ... xs) {

return [=] () {

return async(launch::async, fut_unwrap(f), xs()...);

};

};

}

This function does also first return a function that mimics f because it accepts the same arguments. Then that function returns a callable object that again accepts no arguments. And then that callable object finally differs from the other helper function.

What does the async(launch::async, fut_unwrap(f), xs()...); line mean? The xs()... part means, that all arguments that are saved in pack xs are assumed to be callable objects (like the ones we are creating all the time!), and so they are all called without arguments. Those callable objects that we are producing all the time themselves produce future values, on which we can call get(). This is where fut_unwrap comes into play:

template <typename F>

static auto fut_unwrap(F f)

{

return [f](auto ... xs) {

return f(xs.get()...);

};

}

fut_unwrap just transforms a function f into a function object that accepts a range of arguments. This function object does then call .get() on all of them and then finally forwards them to f.

Take your time to digest all of this. When we used this in our main function, then the auto result (pconcat(...)); call chain did just construct a large callable object that contains all functions and all arguments. No async call was done at this point yet. Then, when we called result(), we unleashed a little avalanche of async and .get() calls that come just in the right order to not block each other. In fact, no get() call happens before not all async calls have been dispatched.

In the end, we can finally call .get() on the future value that result() returned, and there we have our final string.