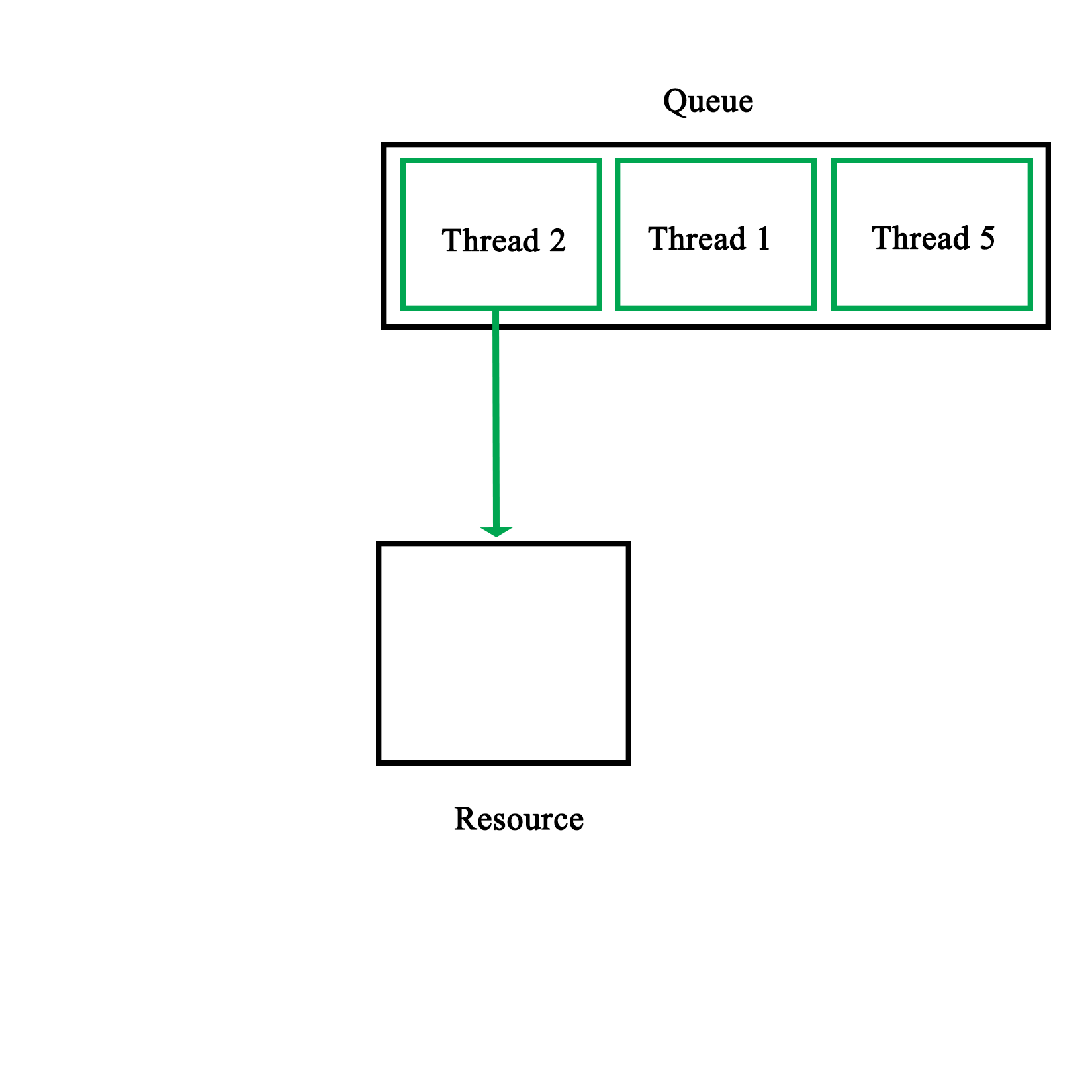

Mutexes form the basis of practically all forms of mutual exclusion APIs. At their core, they seem extremely simple, only one thread can own a mutex, with other threads neatly waiting in a queue until they can obtain the lock on the mutex.

One might even picture this process as follows:

The reality is of course less pretty, mostly owing to the practical limitations imposed on us by the hardware. One obvious limitation is that synchronization primitives aren't free. Even though they are implemented in the hardware, it takes multiple calls to make them work.

The two most common ways to implement mutexes in the hardware is to use either the test-and-set (TAS) or compare-and-swap (CAS) CPU features.

Test-and-set is usually implemented as two assembly-level instructions, which are executed autonomously, meaning that they cannot be interrupted. The first instruction tests whether a certain memory area is set to a 1 or zero. The second instruction is executed only when the value is a zero (false). This means that the mutex was not locked yet. The second instruction thus sets the memory area to a 1, locking the mutex.

In pseudo-code, this would look like this:

bool TAS(bool lock) {

if (lock) {

return true;

}

else {

lock = true;

return false;

}

}

Compare-and-swap is a lesser used variation on this, which performs a comparison operation on a memory location and a given value, only replacing the contents of that memory location if the first two match:

bool CAS(int* p, int old, int new) {

if (*p != old) {

return false;

}

*p = new;

return true;

}

In either case, one would have to actively repeat either function until a positive value is returned:

volatile bool lock = false;

void critical() {

while (TAS(&lock) == false);

// Critical section

lock = 0;

}

Here, a simple while loop is used to constantly poll the memory area (marked as volatile to prevent possibly problematic compiler optimizations). Generally, an algorithm is used for this which slowly reduces the rate at which it is being polled. This is to reduce the amount of pressure on the processor and memory systems.

This makes it clear that the use of a mutex is not free, but that each thread which waits for a mutex lock actively uses resources. As a result, the general rules here are:

- Ensure that threads wait for mutexes and similar locks as briefly as possible.

- Use condition variables or timers for longer waiting periods.