Different programming languages lead to different programming styles. This is, because there are different ways to express things, and they are differing in their elegance for each use case. That is no surprise because every language was designed with specific objectives.

A very special kind of programming style is purely functional programming. It is magically different from the imperative programming which C or C++ programmers are used to. While this style is very different, it enables extremely elegant code in many situations.

One example of this elegance is the implementation of formulas, such as the mathematical dot product. Given two mathematical vectors, applying the dot product to them means pairwise multiplying of the numbers at the same positions in the vector and then summing up all of those multiplied values. The dot product of two vectors (a, b, c) * (d, e, f) is (a * e + b * e + c * f). Of course, we can do that with C and C++, too. It could look like the following:

std::vector<double> a {1.0, 2.0, 3.0};

std::vector<double> b {4.0, 5.0, 6.0};

double sum {0};

for (size_t i {0}; i < a.size(); ++i) {

sum += a[i] * b[i];

}

// sum = 32.0

How does it look like in those languages that can be considered more elegant?

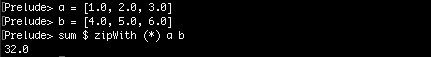

Haskell is a purely functional language, and this is how you can calculate the dot product of two vectors with a magical one-liner:

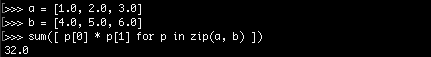

Python is not a purely functional language, but it supports similar patterns to some extent, as seen in the next example:

The STL provides a specific algorithm called std::inner_product, which solves this specific problem in one line, too. But the point is that in many other languages, such code can be written on the fly in only one line without specific library functions that support that exact purpose.

Without delving into the explanations of such foreign syntax, an important commonality in both examples is the magical zip function. What does it do? It takes the two vectors a and b and transforms them to a mixed vector. Example: [a1, a2, a3] and [b1, b2, b3] result in [ (a1, b1), (a2, b2), (a3, b3) ] when they are zipped together. Have a close look at it; it's really similar to how zip fasteners work!

The relevant point is that it is now possible to iterate over one combined range where pairwise multiplications can be done and then summed up to an accumulator variable. Exactly the same happens in the Haskell and Python examples, without adding any loop or index variable noise.

It will not be possible to make the C++ code exactly as elegant and generic as in Haskell or Python, but this section explains how to implement similar magic using iterators, by implementing a zip iterator. The example problem of calculating the dot product of two vectors is solved more elegantly by specific libraries, which are beyond the scope of this book. However, this section tries to show how much iterator-based libraries can help in writing expressive code by providing extremely generic building blocks.