Starting and stopping threads is a very simple thing to do. Multiprogramming starts to be complicated where threads need to work together (sharing resources, waiting for each other, and so on).

In order to start a thread, we first need some function that will be executed by it. The function does not need to be special, as a thread could execute practically every function. Let's pin down a minimal example program that starts a thread and waits for its completion:

void f(int i) { cout << i << 'n'; }

int main()

{

thread t {f, 123};

t.join();

}

The constructor call of std::thread accepts a function pointer or a callable object, followed by arguments that should be used with the function call. It is, of course, also possible to start a thread on a function that doesn't accept any parameters.

If the system has multiple CPU cores, then the threads can run parallel and concurrently. What is the difference between parallel and concurrent? If the computer has only one CPU core, then there can be a lot of threads that run in parallel but never concurrently because one CPU core can only run one thread at a time. The threads are then run in an interleaved way where every thread is executed for some parts of a second, then paused, and then the next thread gets a time slice (for human users, this looks like they run at the same time). If they do not need to share a CPU core, then they can run concurrently, as in really at the same time.

At this point, we have absolutely no control over the following details:

- The order in which the threads are interleaved when sharing a CPU core.

- The priority of a thread, or which one is more important than the other.

- The fact that threads are really distributed among all the CPU cores or if the operating system just pins them to the same core. It is indeed possible that all our threads run on only a single core, although the machine has more than 100 cores.

Most operating systems provide possibilities to control also these facets of multiprogramming, but such features are, at this point, not included in the STL.

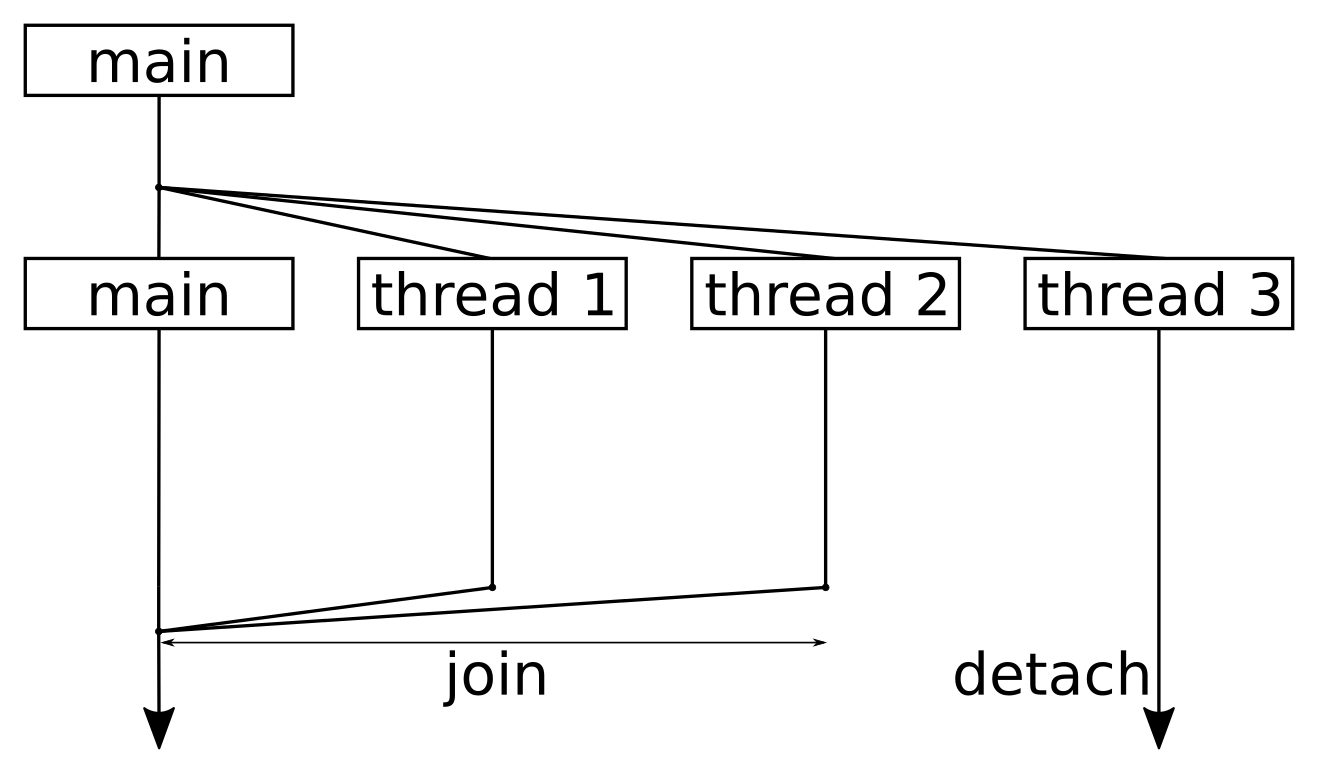

However, we can start and stop threads and tell them when to work on what and when to pause. That should be enough for a large class of applications. What we did in this section was we started three additional threads. Afterward, we joined most of them and detached the last one. Let's summarize in a simple diagram what happened:

Reading the diagram from top to the bottom, it shows one point in time where we split the program workflow to four threads in total. We started three additional threads that did something (namely waiting and printing), but after starting the threads, the main thread executing the main function remained without work.

Whenever a thread has finished executing the function it was started with, it will return from this function. The standard library then does some tidy up work that results in the thread being removed from the operating system's schedule, and maybe in its destruction, but we do not need to worry about it.

The only thing we need to worry about is joining. When a thread calls function x.join() on another thread object, it is put to sleep until thread x returns. Note that we are out of luck if the thread is trapped in an endless loop! If we want a thread to continue living until it decides to terminate itself, we can call x.detach(). After doing so, we have no external control over the thread any longer. No matter what we decide--we must always join or detach threads. If we don't do one of the two, the destructor of the thread object will call std::terminate(), which leads to an abrupt application shutdown.

The moment when our main function returns, the whole application is, of course, terminated. However, at the same time, our detached thread, t3, was still sleeping before printing its bye message to the terminal. The operating system didn't care--it just terminated our whole program without waiting for that thread to finish. This is something we need to consider. If that additional thread had to complete something important, we would have to make the main function wait for it.