In HTTP persistent connection, or HTTP keep-alive, a single TCP/IP connection is used for multiple requests or responses. It has a huge performance improvement over the normal connection as it uses only a single connection instead of opening and closing connections for each and every single request or response. Some of the benefits of the HTTP keep-alive are as follows:

- The load on the CPU and memory is reduced because fewer TCP connections are opened at a time, and no new connections are opened for subsequent requests and responses as these TCP connections are used for them.

- Reduces latency in subsequent requests after the TCP connection is established. When a TCP connection is to be established, a three-way handshake communication is made between a user and the HTTP server. After successfully handshaking, a TCP connection is established. In case of keep-alive, the handshaking is performed only once for the initial request to establish a TCP connection, and no handshaking or TCP connection opening/closing is performed for the subsequent requests. This improves the performance of the requests/responses.

- Network congestion is reduced because only a few TCP connections are opened to the server at a time.

Besides these benefits, there are some side effects of keep-alive. Every server has a concurrency limit, and when this concurrency limit is reached or consumed, there can be a huge degradation in the application's performance. To overcome this issue, a time-out is defined for each connection, after which the HTTP keep-alive connection is closed automatically. Now, let's enable HTTP keep-alive on both Apache and NGINX.

In Apache, keep-alive can be enabled in two ways. You can enable it either in the .htaccess file or in the Apache config file.

To enable it in the .htaccess file, place the following configuration in the .htaccess file:

<ifModule mod_headers.c> Header set Connection keep-alive </ifModule>

In the preceding configuration, we set the Connection header to keep-alive in the .htaccess file. As the .htaccess configuration overrides the configuration in the config files, this will override whatever configuration is made for keep-alive in the Apache config file.

To enable the keep-alive connection in the Apache config file, we have to modify three configuration options. Search for the following configuration and set the values to the ones in the example:

KeepAlive On MaxKeepAliveRequests 100 KeepAliveTimeout 100

In the preceding configuration, we turned on the keep-alive configuration by setting the value of KeepAlive to On.

The next is MaxKeepAliveRequests, which defines the maximum number of keep-alive connections to the web server at the time. A value of 100 is the default in Apache, and it can be changed according to the requirements. For high performance, this value should be kept high. If set to 0, it will allow unlimited keep-alive connections, which is not recommended.

The last configuration is KeepAliveTimeout, which is set to 100 seconds. This defines the number of seconds to wait for the next request from the same client on the same TCP connection. If no request is made, then the connection is closed.

HTTP keep-alive is part of the http_core module and is enabled by default. In the NGINX configuration file, we can edit a few options, such as timeout. Open the nginx config file, edit the following configuration options, and set its values to the following:

keepalive_requests 100 keepalive_timeout 100

The keepalive_requests config defines the maximum number of requests a single client can make on a single HTTP keep-alive connection.

The keepalive_timeout config is the number of seconds that the server needs to wait for the next request until it closes the keep-alive connection.

Content compression provides a way to reduce the contents' size delivered by the HTTP server. Both Apache and NGINX provide support for GZIP compression, and similarly, most modern browsers support GZIP. When the GZIP compression is enabled, the HTTP server sends compressed HTML, CSS, JavaScript, and images that are small in size. This way, the contents are loaded fast.

A web server only compresses content via GZIP when the browser sends information about itself that it supports GZIP compression. Usually, a browser sends such information in Request headers.

The following are codes for both Apache and NGINX to enable GZIP compression.

The following code can be placed in the .htaccess file:

<IfModule mod_deflate.c>

SetOutputFilter DEFLATE

#Add filters to different content types

AddOutputFilterByType DEFLATE text/html text/plain text/xml text/css text/javascript application/javascript

#Don't compress images

SetEnvIfNoCase Request_URI \.(?:gif|jpe?g|png)$ no-gzip dont-

vary

</IfModule>In the preceding code, we used the Apache deflate module to enable compression. We used filter by type to compress only certain types of files, such as .html, plain text, .xml, .css, and .js. Also, before ending the module, we set a case to not compress the images because compressing images can cause image quality degradation.

As mentioned previously, you have to place the following code in your virtual host conf file for NGINX:

gzip on; gzip_vary on; gzip_types text/plain text/xml text/css text/javascript application/x-javascript; gzip_com_level 4;

In the preceding code, GZIP compression is activated by the gzip on; line. The gzip_vary on; line is used to enable varying headers. The gzip_types line is used to define the types of files to be compressed. Any file types can be added depending on the requirements. The gzip_com_level 4; line is used to set the compression level, but be careful with this value; you don't want to set it too high. Its range is from 1 to 9, so keep it in the middle.

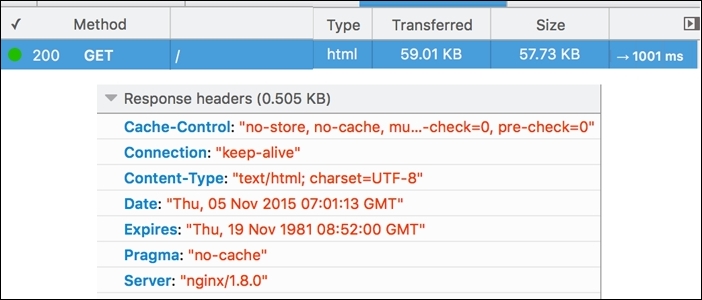

Now, let's check whether the compression really works. In the following screenshot, the request is sent to a server that does not have GZIP compression enabled. The size of the final HTML page downloaded or transferred is 59 KB:

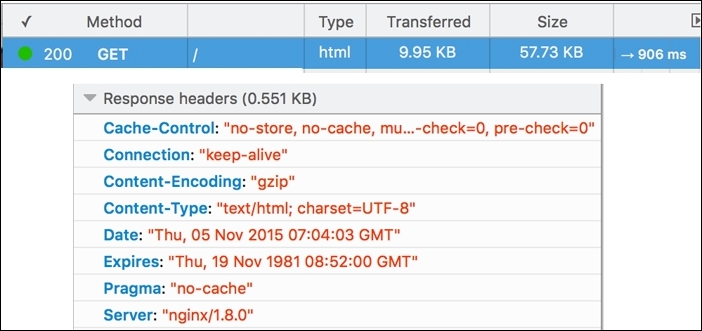

After enabling GZIP compression on the web server, the size of the transferred HTML page is reduced up to 9.95 KB, as shown in the following screenshot:

Also, it can be noted that the time to load the contents is also reduced. So, the smaller the size of your contents, the faster the page will load.

Apache uses the mod_php module for PHP. This way, the PHP interpreter is integrated to Apache, and all processing is done by this Apache module, which eats up more server hardware resources. It is possible to use PHP-FPM with Apache, which uses the FastCGI protocol and runs in a separate process. This enables Apache to worry about HTTP request handlings, and the PHP processing is made by the PHP-FPM.

NGINX, on the other hand, does not provide any built-in support or any support by module for PHP processing. So, with NGINX, PHP is always used in a separate service.

Now, let's take a look at what happens when PHP runs as a separate service: the web server does not know how to process the dynamic content request and forwards the request to another external service, which reduces the processing load on the web server.

Both Apache and NGINX come with lots of modules built into them. In most cases, you won't need some of these modules. It is good practice to disable these modules.

It is good practice to make a list of the modules that are enabled, disable those modules one by one, and restart the server. After this, check whether your application is working or not. If it works, go ahead; otherwise, enable the module(s) after which the application stopped working properly again.

This is because you may see that a certain module may not be required, but some other useful module depends on this module. So, it's best practice it to make a list and enable or disable the modules, as stated before.

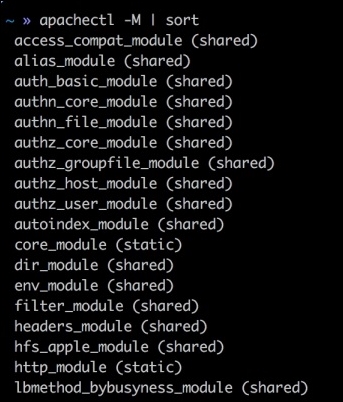

To list all the modules that are loaded for Apache, issue the following command in the terminal:

sudo apachectl –M

This command will list all the loaded modules, as can be seen in the following screenshot:

Now, analyze all the loaded modules, check whether they are needed for the application, and disable them, as follows.

Open up the Apache config file and find the section where all the modules are loaded. A sample is included here:

LoadModule access_compat_module modules/mod_access_compat.so LoadModule actions_module modules/mod_actions.so LoadModule alias_module modules/mod_alias.so LoadModule allowmethods_module modules/mod_allowmethods.so LoadModule asis_module modules/mod_asis.so LoadModule auth_basic_module modules/mod_auth_basic.so #LoadModule auth_digest_module modules/mod_auth_digest.so #LoadModule auth_form_module modules/mod_auth_form.so #LoadModule authn_anon_module modules/mod_authn_anon.so

The modules that have a # sign in front of them are not loaded. So, to disable a module in the complete list, just place a # sign. The # sign will comment out the line, and the module won't be loaded anymore.

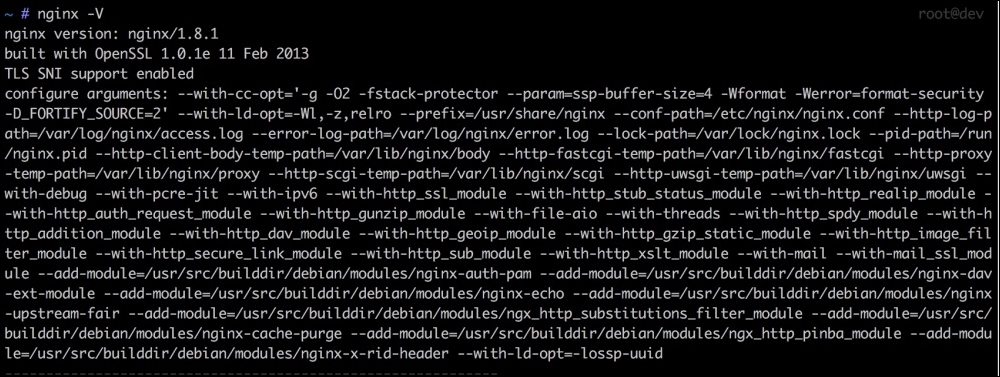

To check which modules NGINX is compiled with, issue the following command in the terminal:

sudo Nginx –V

This will list complete information about the NGINX installation, including the version and modules with which NGINX is compiled. Have a look at the following screenshot:

Normally, NGINX enables only those modules that are required for NGINX to work. To enable any other module that is compiled with NGINX installed, we can place a little configuration for it in the nginx.conf file, but there is no single way to disable any NGINX module. So, it is good to search for this specific module and take a look at the module page on the NGINX website. There, we can find information about this specific module, and if available, we can find information about how to disable and configure this module.

Each web server comes with its own optimum settings for general use. However, these settings may be not optimum for your current server hardware. The biggest problem on the web server hardware is the RAM. The more RAM the server has, the more the web server will be able to handle requests.

NGINX provides two variables to adjust the resources, which are worker_processes and worker_connections. The worker_processes settings decide how many NGINX processes should run.

Now, how many worker_processes resources should we use? This depends on the server. Usually, it is one worker processes per processor core. So, if your server processor has four cores, this value can be set to 4.

The value of worker_connections shows the number of connections per worker_processes setting per second. Simply speaking, worker_connections tells NGINX how many simultaneous requests can be handled by NGINX. The value of worker_connections depends on the system processor core. To find out the core's limitations on a Linux system (Debian/Ubuntu), issue the following command in the terminal:

Ulimit –n

This command will show you a number that should be used for worker_connections.

Now, let's say that our processor has four cores, and each core's limitation is 512. Then, we can set the values for these two variables in the NGINX main configuration file. On Debian/Ubuntu, it is located at /etc/nginx/nginx.conf.

Now, find out these two variables and set them as follows:

Worker_processes 4; Worker_connections 512

The preceding values can be high, specially worker_connections, because server processor cores have high limitations.