Chapter 25 System Logging

System logs are critical for several reasons: These logs provide administrators with useful information to aid in troubleshooting problems. They are also useful in identifying potential hacking attempts. Additionally, logs can be used to provide general information about services, such as which web pages have been provided by a web server.

One area that may complicate matters is the different logging methods available for Linux. Some distributions make use of an older technique called syslog (or newer versions of syslog called rsyslog or syslog-ng), whereas other distributions use a newer technique called journald. Both of these techniques are covered in this chapter.

After reading this chapter and completing the exercises, you will be able to do the following:

View system logs.

Configure syslog to create custom log entries.

Rotate older log files.

View journald logs.

Customize journald.

Syslog

The syslog service has existed since 1980. Although advanced at the time it was created, its limitations have grown over time as more complex logging techniques were required.

In the late 1990s, the syslog-ng service was created to extend the features of the traditional syslog service. Remote logging (including TCP support) was included.

In the mid-2000s, the rsyslog service was created, also as an extension of the traditional syslog service. The rsyslog service includes the ability to extend the syslog capabilities by including modules.

In all three cases, the configuration of the services (the format of syslog.conf file) is consistent, with the exception of slightly different naming conventions (rsyslog.conf, for example) and additional features available in the log files.

The syslogd Daemon

The syslogd daemon is responsible for the logging of application and system events. It determines which events to log and where to place log entries by configuration settings that are located in the /etc/syslog.conf file.

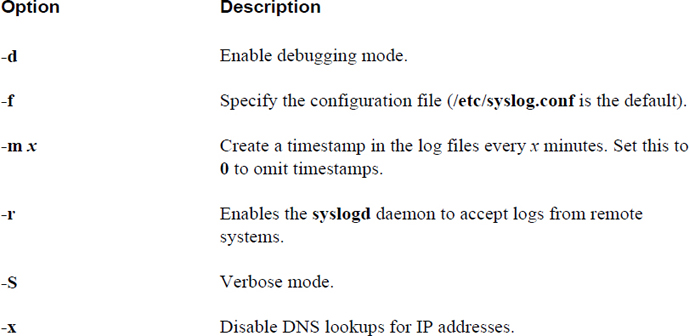

Important options to the syslogd command are displayed in Table 25-1.

Table 25-1 Important syslogd options

Security Highlight

Log entries typically include a timestamp, so using the -m option to introduce additional timestamps is unnecessary and could result in more disk space usage.

Most modern distributions use rsyslogd instead of syslogd. However, from a configuration standpoint, there is very little difference: A few options are different, and the primary configuration file is /etc/rsyslog.conf instead of /etc/syslog.conf.

Keep in mind that the syslog.conf (or rsyslog.conf) file is used to specify what log entries to create. This file is discussed in more detail later in this chapter. You should also be aware that there is a file in which you can specify the syslogd or rsyslogd options. This file varies depending on your distribution. Here are two locations where you might find this file on distributions that use rsyslogd:

• On Ubuntu, go to /etc/default/rsyslog.

• On Fedora, go to /etc/sysconfig/rsyslog.

Regardless of where the file resides, its contents should look something like the following:

root@onecoursesource:~# more /etc/default/rsyslog # Options for rsyslogd # -x disables DNS lookups for remote messages # See rsyslogd(8) for more details RSYSLOGD_OPTIONS=""

You specify the options described in Table 25-1 by using the RSYSLOGD_OPTIONS variable. For example, to configure the current system as a syslog server, use the following:

RSYSLOGD_OPTIONS="-r"

Note

If you are working on an older system that still uses syslogd, the only real difference in terms of this log file is its name (syslog, not rsyslog). Also, rsyslogd supports a few more options that were not mentioned in this chapter.

The /var/log Directory

The /var/log directory is the standard location for log files to be place by the syslogd and rsyslogd daemons. The exact files created by these daemons can vary from one distribution to another. The following describes some of the more commonly created files:

• /var/log/auth.log: Log entries related to authentication operations (typically users logging into the system).

• /var/log/syslog: A variety of log entries are stored in this file.

• /var/log/cron.log: Log entries related to the crond daemon (crontab and at operations).

• /var/log/kern.log: Log entries from the kernel.

• /var/log/mail.log: Log entries from the email server (although Postfix normally stores its log entries in a separate location).

Not all log files in the /var/log directory are created by the syslogd daemon. Many modern services create and manage log files separate from syslogd. Consider the entries from the syslogd daemon as fundamentally part of the operating system, while separate processes (such as web servers, print servers, and file servers) create log files for each process. Exactly what additional files you will find in the /var/log directory depends largely on what services your system is providing.

Security Highlight

The non-syslogd log files are just as important as those managed by syslogd. When you develop a security policy for handling log files, take these additional log files into consideration.

The /etc/syslog.conf File

The /etc/syslog.conf file is the configuration file for the syslogd daemon that tells the daemon where to send the log entries it receives. The following demonstrates a typical syslog.conf file with comments and blank lines removed:

[root@localhost ~]# grep -v "^$" /etc/syslog.conf | grep -v "^#" *.info;mail.none;authpriv.none;cron.none /var/log/messages authpriv.* /var/log/secure mail.* -/var/log/maillog cron.* /var/log/cron *.emerg * uucp,news.crit /var/log/spooler local7.* /var/log/boot.log

Each line represents one logging rule that is broken into two primary parts: the selector (for example, uucp,news.crit) and the action (for example, /var/log/spooler). The selector is also broken into two parts: the facility (for example, uucp,news) and the priority (for example, crit).

The following list shows the available facilities, along with a brief description:

• auth (or security): Log messages related to system authentication (like when a user logs in).

• authpriv: Log messages related to non-system authentication (like when a service such as Samba authenticates a user).

• cron: Log message sent from the crond daemon.

• daemon: Log messages sent from a variety of daemons.

• kern: Log messages sent from the kernel.

• lpr: Log messages sent from older, outdated printer servers.

• mail: Log messages sent from mail servers (typically sendmail).

• mark: Log message designed to place a timestamp in log files.

• news: Log messages for the news server (an outdated Unix server).

• syslog: Log messages generated by syslogd.

• user: User-level log messages.

• uucp: Log messages generated by uucp (an outdated Unix server).

• local0 through local7: Custom log messages that can be generated by nonstandard services or shell scripts. See the discussion of the logger command later in this chapter for more details.

• *: Represents all the facilities.

The following list shows the available priority levels in order from least serious to most serious:

• debug: Messages related to debugging issues with a service.

• info: General information about a service.

• notice: A bit more serious than info messages, but not quite serious enough to warrant a warning.

• warning (or warn): Indicates some minor error.

• err (or error): Indicates a more serious error.

• crit: A very serious error.

• alert: Indicates that a situation must be resolved because the system or service is close to crashing.

• emerg (or panic): The system or service is crashing or has crashed completely.

• *: Represents all the levels.

It is actually the choice of the software developer as to what priority level is used to send a message. For example, the folks who developed the crond daemon may have considered a mistake in a crontab file to be a warning-level priority, or they may have chosen to make it an error-level priority. Generally speaking, debug, info, and notice priority levels are FYI-type messages, whereas warning and error mean “this is something you should look into,” and crit, alert, and emerg mean “do not ignore this; there is a serious problem here.”

Once the severity has been established, the syslogd daemon needs to determine what action to take regarding the log entry. The following list shows the available actions:

• Regular file: A file in the /var/log directory to place the log entry.

• Named pipes: This topic is beyond the scope of this book, but essentially it’s a technique to send the log entry to another process.

• Console or terminal devices: Recall that terminal devices are used to display information in a login session. By sending the message to a specific terminal window, you cause it to be displayed for the user who currently has that terminal window open.

• Remote hosts: Messages are sent to a remote log server.

• User(s): Writes to the specified user’s terminal windows (use * for all users).

Security Highlight

You will see two formats for specifying a file to write log entries to:

/var/log/maillog

-/var/log/maillog

If you do not have a hyphen (the “-” character) before the filename, every log entry will result in the syslogd daemon writing to the hard drive. This will have a performance impact on systems such as mail servers, where each new mail message received or sent would result in a log entry.

If you place a hyphen before the filename, the syslogd daemon will “batch” writes, meaning every log entry does not result in a hard drive write, but rather the syslogd daemon will collect a group of these messages and write them all at one time.

So, why is this a security issue? If your syslogd daemon generates so many hard drive writes that it drastically impacts the performance of the system, then critical operations might fail, resulting in data loss or the inability to access critical data.

Conversational Learning™ — Remote Log Servers

Gary: Julia… got a question for you.

Julia: What’s that?

Gary: I have been asked to send a log message from one of our servers to a remote log server. Why is that important?

Julia: Ah, this is common on system-critical servers, especially if they have a presence on the Internet. Pretend for a moment that you are a hacker and you have gained unauthorized access the server in question. Once you have access, you probably want to hide your tracks. Guess what you will probably do?

Gary: Oh, I see! I’d delete the log files! Then nobody could tell how I accessed the system. Shoot, they might not even know that I have accessed the system at all!

Julia: Right, but what if those log files were also copied over to another server?

Gary: Ah, then it would be much harder to hide my tracks. I’d have to hack into yet another system, probably one that has different accounts and services, making it much more difficult.

Julia: And now you know why you want a copy of the log files sent to another server.

Gary: Thanks, Julia!

Julia: Always happen to help out, Gary.

The /etc/rsyslog.conf File

Most modern systems make use of the rsyslogd daemon instead of the syslogd daemon. The newer rsyslod daemon has more functionality, but most of the features of the older syslogd daemon still work.

For example, although there are features in the /etc/rsyslog.conf file that do not exist in the /etc/syslog.conf file, the contents described earlier in this chapter are still valid for the newer configuration file.

You should be aware of a few features that are new to the /etc/rsyslog.conf file. One feature is the ability to use modules. Modules provide more functionality; for example, the following module will allow the rsyslogd daemon to accept log messages from remote systems via the TCP protocol:

# provides TCP syslog reception #$ModLoad imtcp #$InputTCPServerRun 514

Also, a new section in the /etc/rsyslog.conf file called GLOBAL DIRECTIVES allows you to provide settings for all log file entries. For example, the following will set the user owner, group owner, and permissions of any new log file that is created by the rsyslogd daemon:

# Set the default permissions for all log files. # $FileOwner syslog $FileGroup adm $FileCreateMode 0640

The last major change is that most log rules are not stored in the /etc/rsyslog.conf file, but rather in files in the /etc/rsyslog.d directory. These files can be included in the main configuration file as follows:

# Include all config files in /etc/rsyslog.d/ # $IncludeConfig /etc/rsyslog.d/*.conf

By using an “include” directory, you can quickly add or remove large sets of log rules by adding or removing a file from the directory.

Creating Your Own /etc/syslog.conf Entry

The ability to read existing /etc/syslog.conf entries is important, but being able to create your own entries is also useful. Creating an entry consists of modifying the /etc/syslog.conf file first, then restarting the syslogd server. After the syslogd server has restarted, you should test your new entry by using the logger command.

Adding an Entry

First, determine what sort of entry you want to capture. For example, typically all crond daemon log messages are sent to the /var/log/cron file because of the following entry in the /etc/syslog.conf file:

cron.* /var/log/cron

What if you also want cron messages at crit priority and higher sent to the root user’s terminal window. You could add the following entry to the /etc/syslog.conf file:

cron.critroot

When you specify a priority, all messages at that priority level and above (more serious) are sent to the destination. To capture only messages at a specific priority level, use the following syntax:

cron.=critroot

Another way of sending messages is from a script that you create. You can issue logger commands (see the next section) within your script to create log entries, but you do not want to use the standard facilities, such as cron and mail, as these are associated with specific services already. Instead, use one of the custom facilities (local0, local1, and so on). The highest of these values is local7. Here’s an example:

local7.* /var/log/custom

After making these changes and saving the /etc/syslog.conf file, restart the syslogd service (see Chapter 28, “System Booting,” for details about restarting services). Then use the logger command to test your new entry.

What Could Go Wrong?

Errors in the /etc/syslog.conf file could have an impact on existing log rules. Make sure you always use the logger command to test new rules.

Using the logger Command

The logger utility can be used to send a log entry to the syslogd daemon:

[root@localhost ~]# logger -p local7.warn "warning"

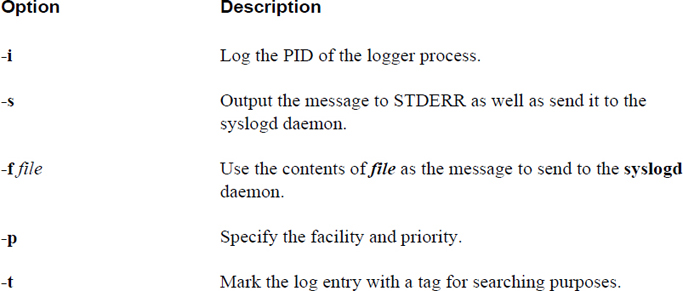

Important options to the logger command are provided in Table 25-2.

Table 25-2 Important logger Command Options

The logrotate Command

The logrotate command is a utility designed to ensure that the partition that holds the log files has enough room to handle the log files. Log file sizes increase over time as more entries are added. The logrotate command routinely makes backup copies of older log files and eventually removes older copies, limiting the filesystem space that the logs use.

This command is configured by the /etc/logrotate.conf file and files in the /etc/logrotate.d directory. Typically the logrotate command is configured to run automatically as a cron job:

[root@localhost ~]# cat /etc/cron.daily/logrotate

#!/bin/sh

/usr/sbin/logrotate /etc/logrotate.conf

EXITVALUE=$?

if [ $EXITVALUE != 0 ]; then

/usr/bin/logger -t logrotate "ALERT exited abnormally with [$EXITVALUE]"

fi

exit 0

The /etc/logrotate.conf File

The /etc/logrotate.conf file is the primary configuration file for the logrotate command. A typical /etc/logrotate.conf file looks like Example 25-1.

Example 25-1 Typical /etc/logrotate.conf File

[root@localhost ~]#cat /etc/logrotate.conf

# see "man logrotate" for details

# rotate log files weekly

weekly

# keep 4 weeks worth of backlogs

rotate 4

# create new (empty) log files after rotating old ones

create

# uncomment this if you want your log files compressed

#compress

# RPM packages drop log rotation information into this directory

include /etc/logrotate.d

# no packages own wtmp -- we'll rotate them here

/var/log/wtmp {

monthly

minsize 1M

create 0664 root utmp

rotate 1

}

The top part of the /etc/logrotate.conf file is used to enable global settings that apply to all files that are rotated by the logrotate utility. These global settings can be overridden for individual files by a section defined like the following:

/var/log/wtmp {

monthly

minsize 1M

create 0664 root utmp

rotate 1

}

Typically these sections are found in files located in the /etc/logrotate.d directory, but they can be placed directly in the /etc/logrotate.conf file, as in the previous example of /var/log/wtmp.

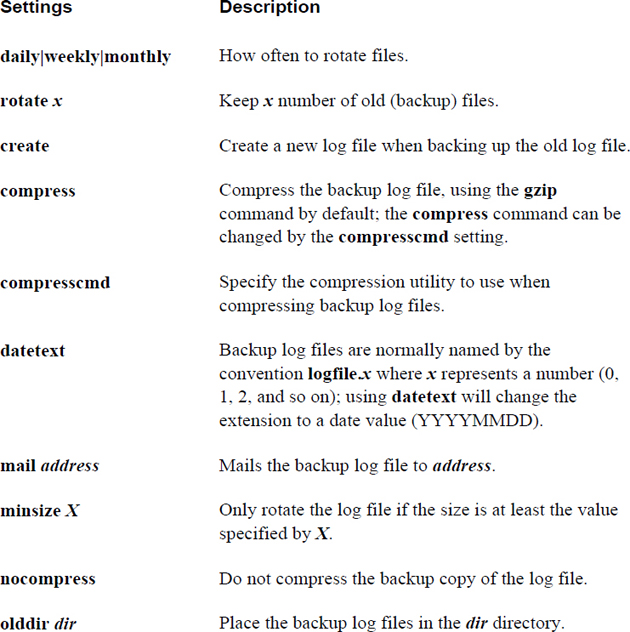

Important settings in the /etc/logrotate.conf file include those shown in Table 25-3.

Table 25-3 Settings in the /etc/logrotate.conf File

Files in the /etc/logrotate.d directory are used to override the default settings in the /etc/logrotate.conf file for the logrotate utility. The settings for these files are the same as the settings for the /etc/logrotate.conf file.

By using this “include” directory, you can easily insert or remove log rotate rules by adding or deleting files in the /etc/logrotate.d directory.

The journalctl Command

On modern Linux systems, the logging process is handled by the systemd-journald service. To query systemd log entries, use the journalctl command, as shown in Example 25-2.

Example 25-2 Using the journalctl Command

[root@localhost ~]#journalctl | head -- Logs begin at Tue 2019-01-24 13:43:18 PST, end at Sat 2019-03-04 16:00:32 PST. -- Jan 24 13:43:18 localhost.localdomain systemd-journal[88]: Runtime journal is using 8.0M (max allowed 194.4M, trying to leave 291.7M free of 1.8G available → current limit 194.4M). Jan 24 13:43:18 localhost.localdomain systemd-journal[88]: Runtime journal is using 8.0M (max allowed 194.4M, trying to leave 291.7M free of 1.8G available → current limit 194.4M). Jan 24 13:43:18 localhost.localdomain kernel: Initializing cgroup subsys cpuset Jan 24 13:43:18 localhost.localdomain kernel: Initializing cgroup subsys cpu Jan 24 13:43:18 localhost.localdomain kernel: Initializing cgroup subsys cpuacct Jan 24 13:43:18 localhost.localdomain kernel: Linux version 3.10.0-327.18.2.el7.x86_64 (builder@kbuilder.dev.centos.org) (gcc version 4.8.3 20140911 (Red Hat 4.8.3-9) (GCC) ) #1 SMP Thu May 12 11:03:55 UTC 2016 Jan 24 13:43:18 localhost.localdomain kernel: Command line: BOOT_IMAGE=/vmlinuz-3.10.0-327.18.2.el7.x86_64 root=/dev/mapper/centos-root ro rd.lvm.lv=centos/root rd.lvm.lv=centos/swap crashkernel=auto rhgb quiet LANG=en_US.UTF-8 Jan 24 13:43:18 localhost.localdomain kernel: e820: BIOS-provided physical RAM map: Jan 24 13:43:18 localhost.localdomain kernel: BIOS-e820: [mem 0x0000000000000000-0x000000000009fbff] usable

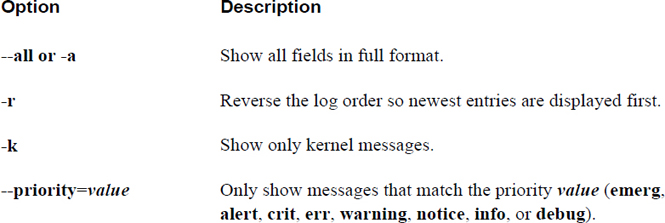

Important options to the journalctl command include those shown in Table 25-4.

Table 25-4 Options to the journalctl Command

The /etc/systemd/journald.conf file

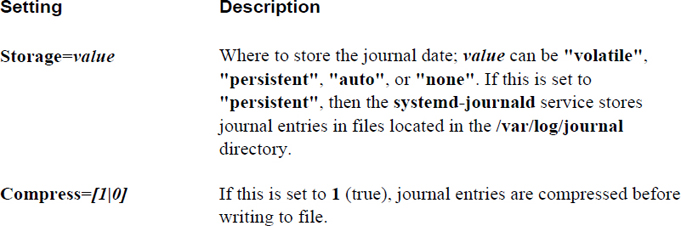

The /etc/systemd/journald.conf file is used to configure the systemd-journald service. Typically this file contains all commented-out values by default. Important settings for the /etc/systemd/journald.conf file include those shown in Table 25-5.

Table 25-5 Settings for the /etc/systemd/journald.conf File

Summary

In this chapter, you explored how to view and create log file entries using one of the syslogd services. You also learned how to prevent log files from growing to the size that quickly fills the /var partition.

Key Terms

Review Questions

1. The /etc/_____ file is the primary configuration file for the rsyslogd daemon.

2. Which syslog facility is used to log messages related to non-system authentication?

a. auth

b. authpriv

c. authnosys

d. authsys

3. Log entries that are generated by the kernel are typically stored in the /var/log/_____ file.

4. The _____ syslog priority indicates that the system or a service has crashed.

a. info

b. warning

c. crit

d. emerg

5. The _____ command can be used to send a log entry to the syslogd daemon.