Chapter 8 Develop an Account Security Policy

An important component of this book is the focus on making systems more secure. In modern IT environments, security is a very important topic, and learning how to secure a system early will help you strengthen your Linux skill set.

Most of the parts in this book end with a chapter that focuses just on security. In these chapters, you learn how to secure a particular component of Linux. The focus of this chapter is on securing your group and user accounts.

You have a large number of tools and features available to you to help you secure Linux. Although not all of these can be covered in this book, you will be exposed to a good variety of them.

After reading this chapter and completing the exercises, you will be able to do the following:

Use Kali Linux to perform security probes on systems.

Create a security policy for user accounts.

Introducing Kali Linux

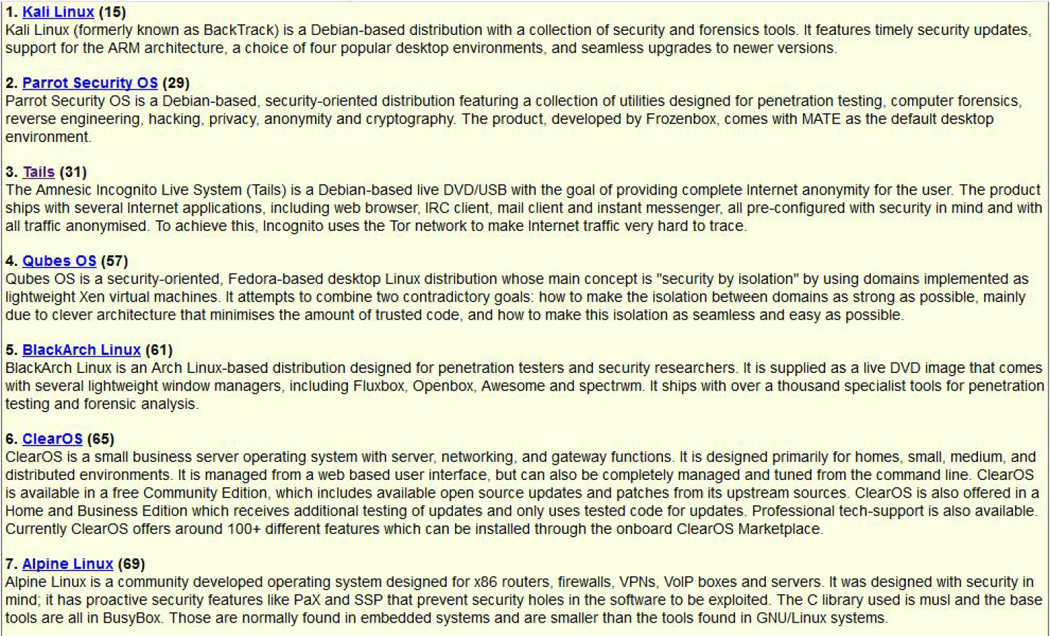

Previously we discussed different Linux distributions, including how some distributions are very focused on a specific feature. There are many security-based distributions, some of which are natively more secure by default. Others provide tools and features designed for you to enhance security in your environment. Figure 8-1 displays the most popular security-based Linux distributions, according to distrowatch.com.

Figure 8-1 Popular Security-Based Distributions

One of the more popular distributions is Kali Linux, a distro designed to provide you with tools to test security. We will make use of this distribution throughout this book. After you install Kali Linux, you can access the tools by clicking Applications, as demonstrated in Figure 8-2.

Figure 8-2 Kali Linux Applications

The tools are broken into different categories. For example, the “Password Attacks” category includes tools to test the strength of the passwords for user accounts. We will not cover all the tools are available on Kali Linux, but each part of this book does include a discussion about some of the more important tools, and you can explore the others on your own.

Security Principles

The term security should be better defined before we continue any further. Although it may seem like a simple term, it is rather complex.

Most people think of “security” as something designed to keep hackers from getting into a system, but it really encompasses much more than that. Your goal in terms of security is to make systems, services, and data available to the correct entities while denying access to these entities by unauthorized entities.

We use the term entities because we are not just referring to people. For example, you may have a service that provides user account information to other systems. This information should not be provided to systems that are not supposed to have access. So, providing access to the service and the data provided by the service is done for specific systems, not specific people.

You also have to find the right balance between making a system secure and making it available. In other words, if you lock a system down so tightly that authorized entities cannot get the required access, you have essentially made the system less secure.

You also have to keep an eye on authorized users who may attempt to gain unauthorized access. Internal users have an edge because they already are past one level of security since they have access using their own accounts. They also tend to be trusted by default, so security personal and administrators often overlook them as a source of unauthorized access.

External hackers may also try to compromise your security by making a system deny access to authorized entities (actually, internal hackers may also do this). Some people take great delight in making key servers (like your web server) inaccessible, or in posting embarrassing messages to harm the company’s reputation.

Obviously there is a lot to consider when putting together a plan to secure your Linux systems, and you will find that no single book is going to address everything. But, just suppose for a moment that there was such a book and suppose that you followed every suggestion provided by this magical book. Even then, your systems would not be 100% secure. There is always a way to compromise a system if someone has enough time, resources, and knowledge. Securing a system is a job that is never complete, and a security plan should go through consistent revision as you learn more and discover new techniques.

Consider securing a Linux system or network similar to securing a bank. You have likely seen movies or TV shows where a complicated bank security system is compromised by very clever and determined thieves. It is your goal to make your system so secure that it requires very clever and determined hackers in order to have a chance to compromise it.

Creating a Security Policy

A good security policy is one that provides a blueprint for administrators and users to follow. It should include, at the very least, the following:

• A set of rules that determines what is and is not allowed on systems. For example, this set of rules could describe the password policy that all users must follow.

• A means to ensure that all rules are being followed. This could include actively running programs that probe system security as well as viewing system log files for suspicious activity.

• A well-defined plan to handle when a system is compromised. Who is notified, what actions should be taken, and so on. This is often referred to as an incident response plan.

• A way to actively change the policy as new information becomes available. This information should be actively sought out. For example, most distributions have a way to learn about new vulnerabilities and tools such as patches and updates, as well as techniques to address those vulnerabilities.

Securing Accounts

You must consider several components when securing user accounts. These include the following:

• Physical security of the system or network

• Education of users

• Ensuring accounts are not susceptible to attack

Physical Security

Often IT security personnel will neglect to consider physical security as part of the security policy. This is sometimes the result of thinking “physical security is not a responsibility of the IT department,” as many companies have a separate department that is in charge of physical security. If this is the case, the two departments should work together to ensure the best overall security policy. If this is not the case, then physical security may be entirely the responsibility of the IT department.

When crafting a policy that includes physical security, you should consider the following:

• Secure physical access to the systems in your organization, particularly the mission-critical servers, such as mail and web servers. Be sure to consider which systems have the necessary access and authority to make changes on other systems.

• Secure physical access to the network. Unauthorized people should not have physical access to any network assets.

• Prevent unauthorized people from viewing your systems, particularly the terminal windows. Hackers can use information gathered from viewing keyboard input and data displayed on terminal windows. This information can be used to compromise security.

• Password-protect the BIOS of mission-critical systems, especially if these systems cannot be 100% physically secured.

• Protect systems from theft and hardware errors.

There are many other aspects to physical security that you should consider. The purpose of this section is to encourage you to think about including physical security as part of how you secure your systems. Consider this the first line of defense of a multilayer security policy.

Educating Users

Years ago one of the authors of this book was teaching a Linux security class and he said (mostly as a joke) “whatever you do, don’t write down your password and tape it under your keyboard.” After a good chuckle by the class, one student said “no one really does that, do they?” During the lunch break, some of the students took a trip around their office, flipping over keyboards and discovering three passwords. Actually, a fourth password was found taped to the monitor of the employee.

Clearly, users play a critical role in the security policy. Often they are unaware of how their actions can compromise security. When creating the security policy, you should consider how to encourage users to make your system more secure, rather than less secure. For example, consider the following:

• Encourage users to use strong passwords.

• Warn users about installing software that is not approved or supported by your organization.

• Encourage users to report any suspicious activity immediately.

• Ask users to be careful about accessing system-critical systems when logged into unsecure locations (like a public Wi-Fi spot). If users must access system-critical systems from unsecure locations, consider implementing a VPN (virtual private network) technology.

• Warn users that they should never share their accounts or passwords with anyone.

• Educate users about clicking links from emails or opening attachments from unknown sources. These often contain viruses or worms, or they may be a spoofing attempt (an attempt to gain account information by pretending to be a valid resource). Even if the sender is known or trusted, if their email account is compromised, the messages may contain malware.

Educating users is a fairly large topic by itself, but one that you should spend considerable time and effort on when putting together a security policy. We encourage you to explore this topic more, as further discussion is beyond the scope of this book.

Account Security

You can take specific actions on the system in order to make accounts more secure. Some of these actions will be covered later in this book. For example, you can make user accounts more secure by using the features of PAM (Pluggable Authentication Modules), a topic that was covered in detail in Chapter 7, “Managing User Accounts.” Another example: Chapter 25, “System Logging,” discusses using system logs—a topic that is important when it comes to securing user accounts. System logs are used to determine if someone is trying to gain unauthorized access to a system.

This section covers a collection of user account security topics. Each topic is briefly explained, and then we provide an idea of how you would incorporate the topic within a security policy.

User Account Names

Consider that for a hacker to gain unauthorized access to a system, they would need two pieces of information: a username and a user password. Preventing a hacker from being able to figure out a username would make the process of hacking into your systems more difficult. Consider using account names that are not easy to guess.

For example, do not create an account named “bsmith” for Bob Smith. This would be easy for a hacker to guess if the hacker knows that Bob Smith works for the company. Consider something like “b67smith” instead for a user account name. Remember, your employees may be named on the company website or in news that identifies their relationship to the company.

Incorporate this into a security policy: Create a rule that all user accounts must be something that is not easy to guess by knowing the person’s real name. Also use mail aliases (see Chapter 20, “Network Service Configuration: Essential Services”) to hide usernames from the outside world.

Users with No Password

As you can probably guess, a user with no password poses a considerable security risk. With no password at all in the /etc/shadow file, only the user’s name is required to log into the system.

Incorporate this into a security policy: Create a crontab entry (see Chapter 14, “Crontab and At,” for information about crontab entries) to execute the following command on a regular basis: grep "^[^:]*::" /etc/shadow. Alternately, you can use one of the security tools covered later in this chapter.

Preventing a User from Changing a Password

In certain use cases, you do not want a user to change the account password. For example, suppose you have a guest account, designed for restricted system access for non-employees. You do not want whoever uses this account to change the password because that would prevent the next guest from using the account.

If you make the min field of the /etc/shadow file a higher value than the max field, then the user cannot change the account password (note: on some distributions, like Kali, the options are -n for the min field and -x for the max field):

passwd -m 99999 -M 99998 guest

Incorporate this into a security policy: Determine which accounts should have this restriction and apply the restriction as needed. Remember to change the password regularly so past “guests” may not access the system later simply because they know the password.

Application Accounts

The guest account that was described in the previous example could also be an application account. For an application account, only command-line login should be permitted (no GUI should be displayed on the system). Then, change the last field of the /etc/passwd file for the user to an application, like the following:

guest:x:9000:9000:Guest account:/bin/guest_app

The /bin/guest_app would run a program that provides limited access to the system. You could also consider using a restricted shell, as described in Chapter 7, if you want the account to have access to more than one application.

Incorporate this into a security policy: Determine which accounts should have this restriction and apply the restriction as needed.

Enabling Process Accounting

A software tool called psacct can be used to keep track of all commands executed by users. This is very important on systems where you suspect hacking attempts might be successful. This tool needs to be downloaded and then installed using the following steps:

1. Download the tool from http://ftp.gnu.org/gnu/acct/.

2. Execute the gunzip acct* command to unzip the downloaded file.

3. Execute the tar -xvf acct* command to extract the file contents.

4. Execute the cd command to change into the directory that was created by the tar command.

5. Execute the ./configure; make; make install command to install the software.

After the software has been installed, you can start the service by first creating the log file where the service will store data:

mkdir /var/log/account touch /var/log/account/pact

Then start the service with the following command:

accton on

After the service has been started, you can view commands executed by using the lastcomm command:

root@onecoursesource:~# lastcomm more root pts/0 0.00 secs Sun Feb 25 15:42 bash F root pts/0 0.00 secs Sun Feb 25 15:42 kworker/dying F root __ 0.00 secs Sun Feb 25 15:31 cron SF root __ 0.00 secs Sun Feb 25 15:39 sh S root __ 0.00 secs Sun Feb 25 15:39 lastcomm root pts/0 0.00 secs Sun Feb 25 15:37 accton S root pts/0 0.00 secs Sun Feb 25 15:37

Useful information is also provided by the ac command. For example, to see a summary of all login times for each user in the last 24 hours, use the ac -p --individual-totals command.

Incorporate this into a security policy: On critical systems that may be venerable (such as web and mail servers), incorporate this software package and use a crontab entry (see Chapter 14 for information about crontab entries) to generate regular reports (hourly or daily).

Avoiding Commands Being Run as the Superuser

A large number of anecdotal stories involve system administrators creating destruction and wreaking havoc on systems because of commands that were run as the root user accidently. Consider a situation in which you run the rm -r /* command. As a regular user, you may end up deleting your own files, but permissions (discussed in Chapter 9, “File Permissions”) prevent you from deleting any files on the system that you don’t own. However, if that command is run by someone logged in as the root user, then all files could be destroyed.

Incorporate this into a security policy: Always log in as a regular user and use the sudo or su command’s permission (see Chapter 9 for details about sudo and su) to gain temporary root access. When you’re finished running the command that required root access, return to the regular account.

Security Tools

Many security tools can be used to search for security weaknesses. This section describes and demonstrates several of these tools using Kali Linux, but these tools can be installed and used on other distributions as well. The advantage of Kali Linux is that these tools are installed and configured by default.

On Kali Linux, most of these tools can be accessed by clicking Applications and then 05 – Password Attacks, as demonstrated in Figure 8-3.

Figure 8-3 Password Attacks

You might also consider exploring “13 – Social Engineering Tools.” Social engineering is a technique for gathering system information from users by using nontechnical methods. For example, a hacker might call an employee pretending to be a member of the company’s IT support team and attempt to gather information from the employee (like their username, password, and so on).

The john and Johnny Tools

The john utility (full name: John the Ripper) is a command-line password hacking tool. The advantage of a command-line tool is that it is something that you can automate via a crontab entry (see Chapter 14 for information about crontab entries), allowing you to schedule this tool to run on a regular basis.

The Johnny utility is a GUI-based version of the john utility. The advantage of this GUI tool is that it allows you to run john commands without having to memorize all of the command options.

In both cases, you need to have a file that contains both /etc/passwd and /etc/shadow entries. You can make this file by running the following command:

cat /etc/passwd /etc/shadow > file_to_store

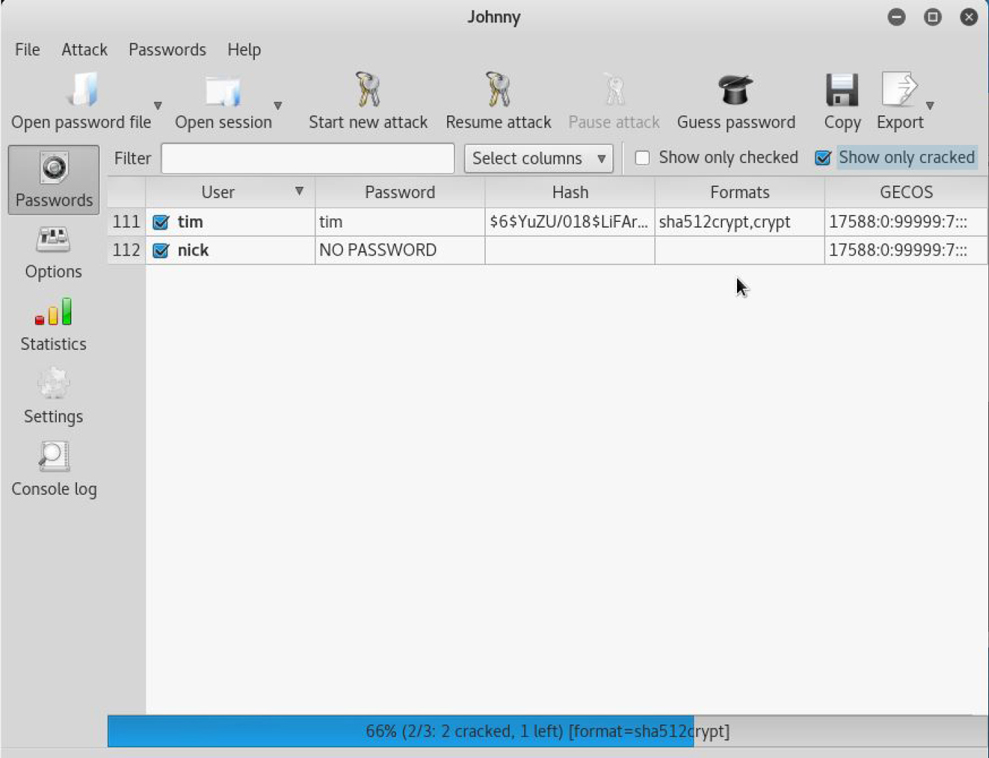

When running Johnny, you can load this file into the utility by clicking the Open password file option. Next, select the accounts you want to try to crack and then click the Start new attack button. Each account appears as it is cracked, as shown in Figure 8-4.

Figure 8-4 Cracked Passwords

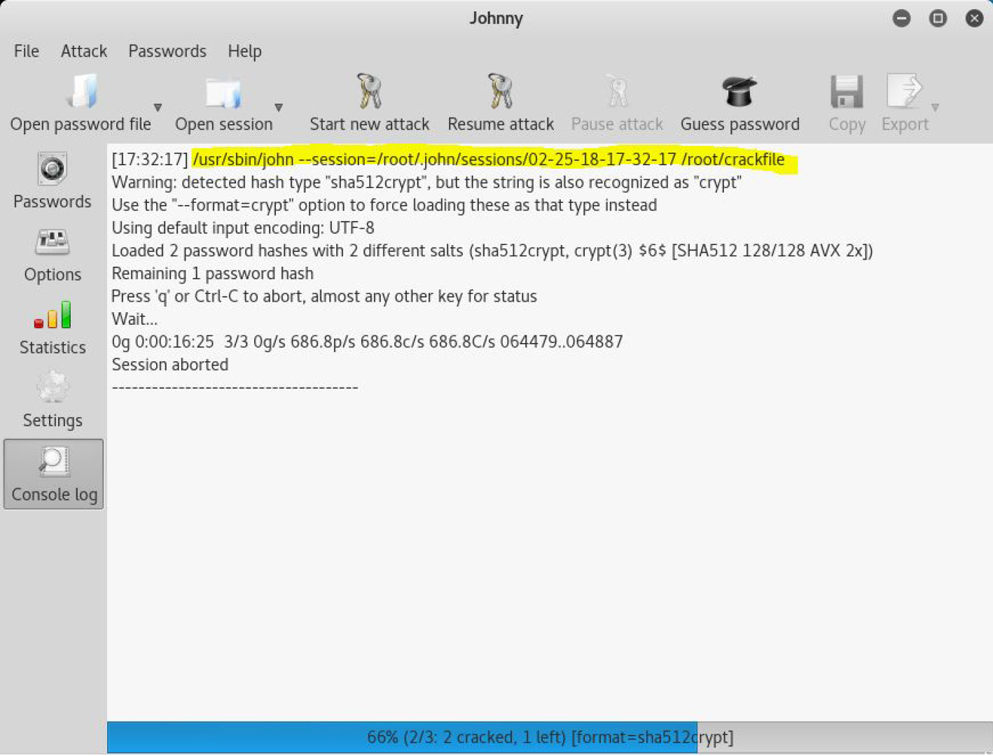

To see what john command was executed, click the Console log button, as shown in Figure 8-5.

Figure 8-5 The john Command

The hydra tool

Whereas the john utility makes use of a file of user accounts and passwords, the hydra tool actively probes a system via a specific protocol. For example, the following command would use the hydra tool to attack the local system via FTP (File Transfer Protocol):

hydra -l user -P /usr/share/set/src/fasttrack/wordlist.txt ftp://127.0.0.1

Note that you should not run a command like this on any system for which you do not have written authorization to perform security analysis. Attempts to run this command on another organization’s system can be considered an illegal hacking attempt.

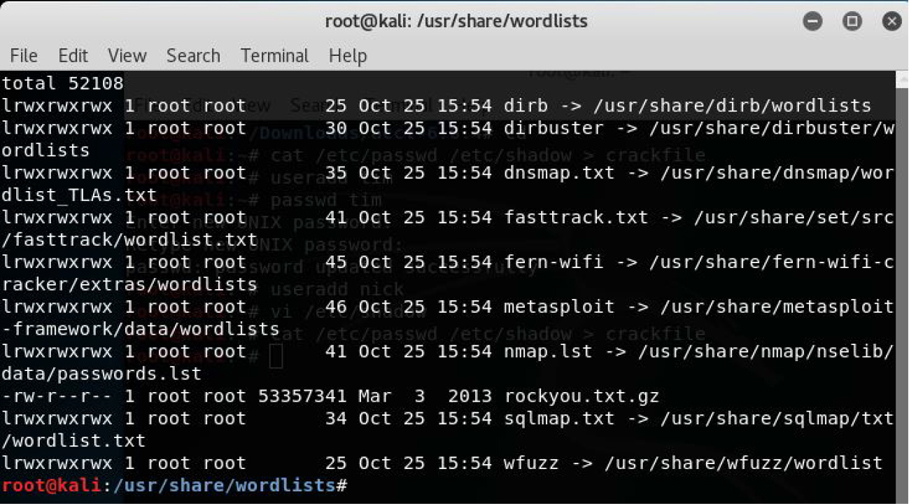

The wordlist file is one of many available on the system. Click Applications, 05 – Password Attacks, wordlists to display a list of word files, as shown in Figure 8-6.

Figure 8-6 Displaying Wordlists

You can also find many wordlists online.

Summary

You have started the process of learning how to create a security policy. At the end of the five main parts of this book, you will expand on this knowledge. Based on what you learned in this chapter, you should have the information you need to create a security policy for user accounts, including using tools provided by Kali Linux to perform security scans.

Review Questions

1. Fill in the missing option so the user of the bob account can’t change his password: passwd _____ 99999 -M 99998 bob

2. Which command can be used to find users who have no password?

a. find

b. grep

c. passwd

d. search

3. The _____ package provides process accounting.

4. Which of the following utilities can be used to perform password-cracking operations?

a. john

b. nick

c. jill

d. jim

5. Which command can be used to switch from a regular user to the root user?

a. switch

b. sed

c. du

d. su