Linux Essentials for Cybersecurity

Copyright © 2019 by Pearson Education, Inc.

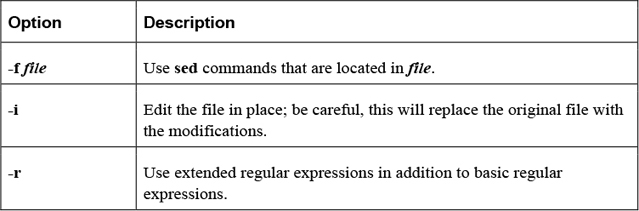

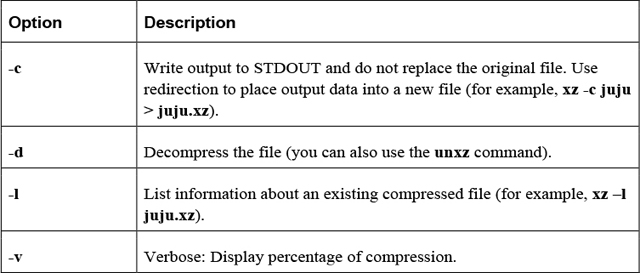

All rights reserved. No part of this book shall be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher. No patent liability is assumed with respect to the use of the information contained herein. Although every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the publisher and author assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. Nor is any liability assumed for damages resulting from the use of the information contained herein.

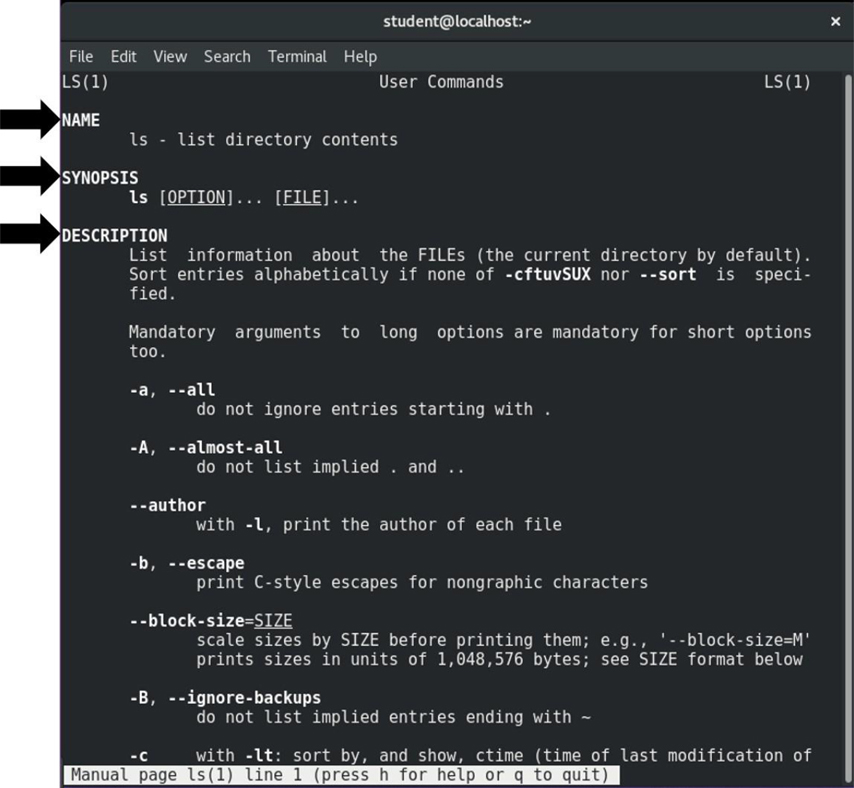

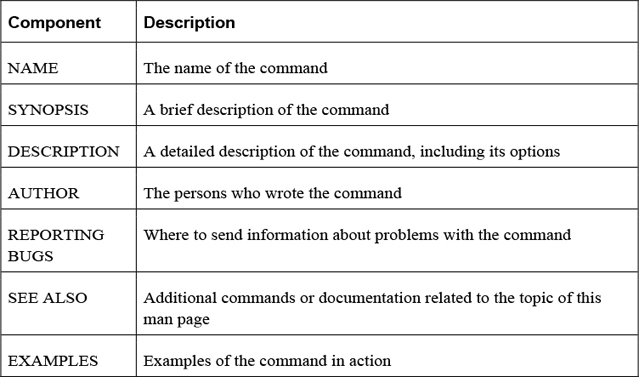

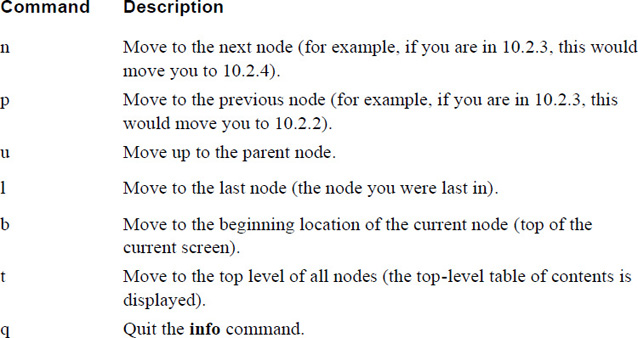

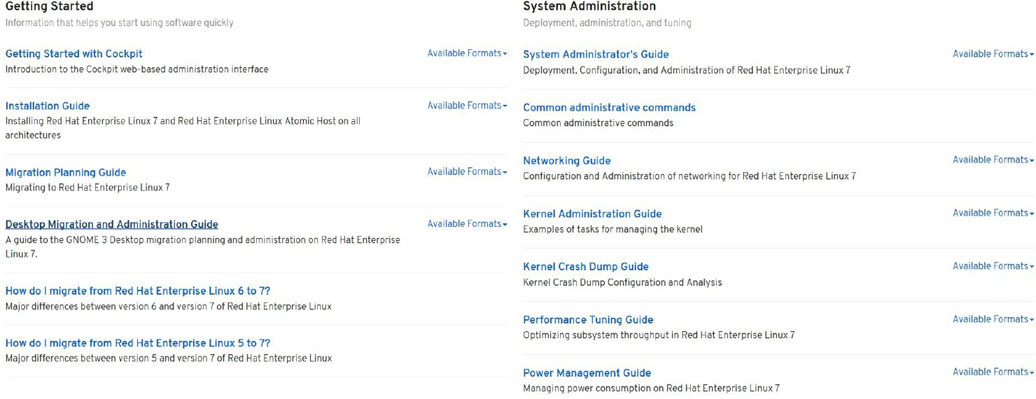

ISBN-13: 978-0-7897-5935-1

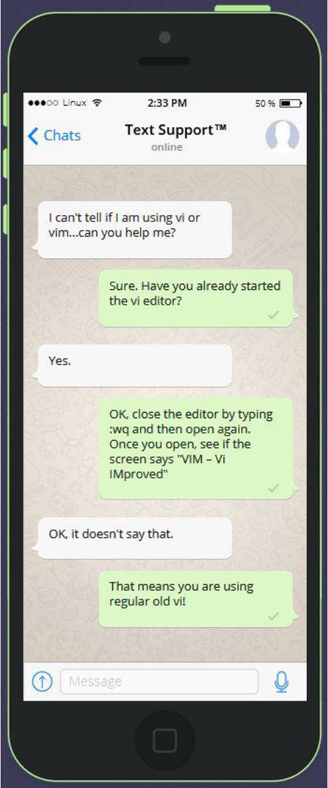

ISBN-10: 0-7897-5935-7

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018941152

First Printing: July 2018

Trademarks

All terms mentioned in this book that are known to be trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capitalized. Pearson IT Certification cannot attest to the accuracy of this information. Use of a term in this book should not be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark.

Warning and Disclaimer

Every effort has been made to make this book as complete and as accurate as possible, but no warranty or fitness is implied. The information provided is on an “as is” basis. The authors and the publisher shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damages arising from the information contained in this book.

Special Sales

For information about buying this title in bulk quantities, or for special sales opportunities (which may include electronic versions; custom cover designs; and content particular to your business, training goals, marketing focus, or branding interests), please contact our corporate sales department at corpsales@pearsoned.com or (800) 382-3419.

For government sales inquiries, please contact governmentsales@pearsoned.com.

For questions about sales outside the U.S., please contact intlcs@pearson.com.

Editor-In-Chief: Mark Taub

Product Line Manager: Brett Bartow

Executive Editor: Mary Beth Ray

Development Editor: Eleanor Bru

Managing Editor: Sandra Schroeder

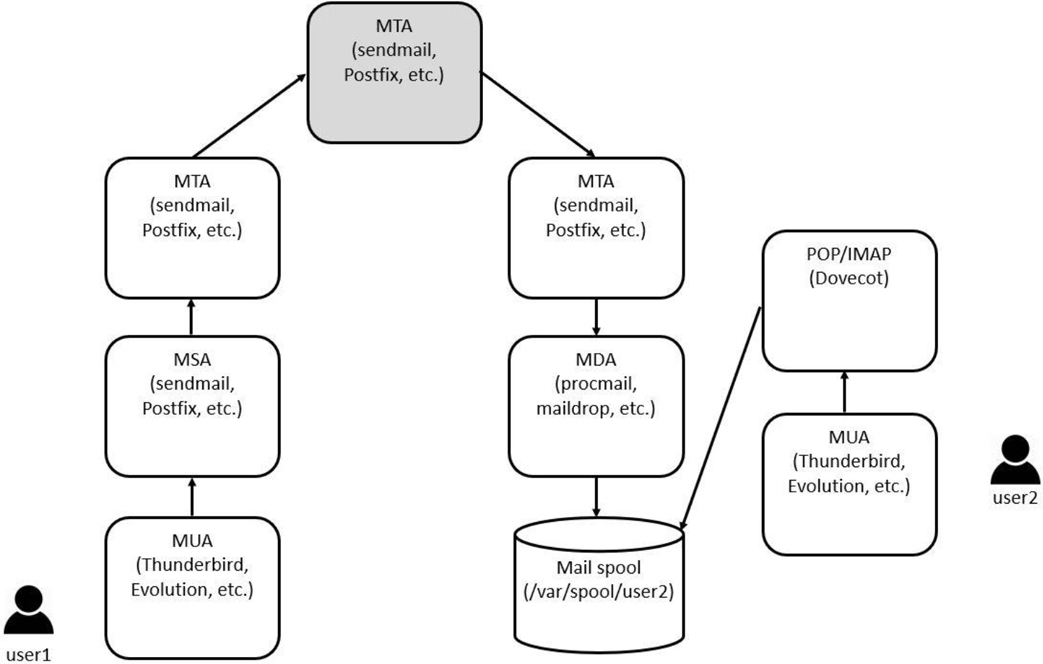

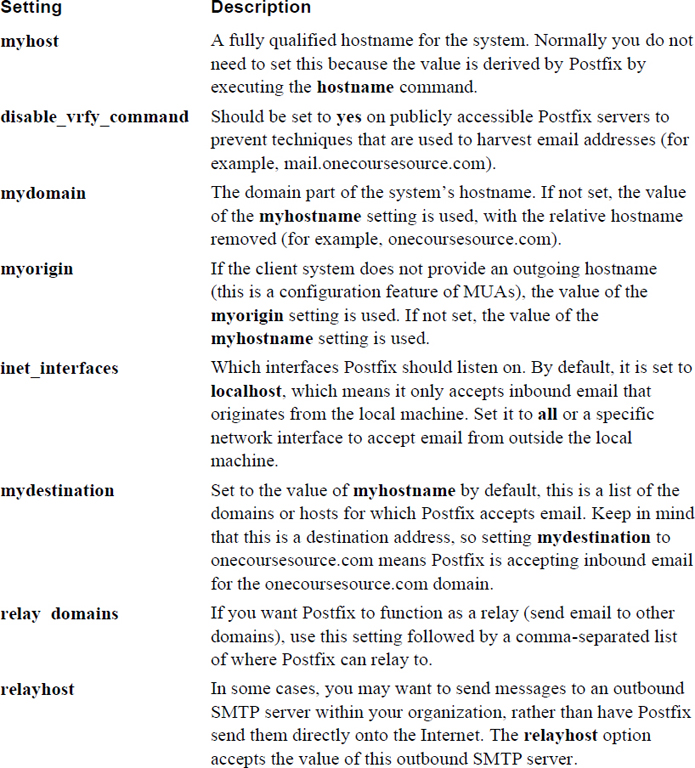

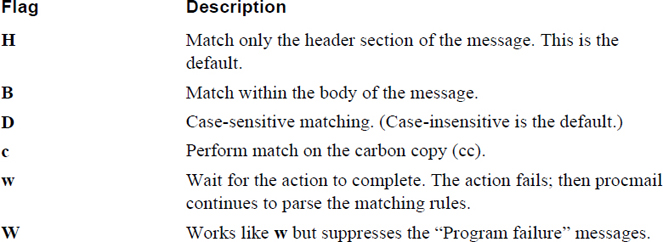

Senior Project Editor: Mandie Frank

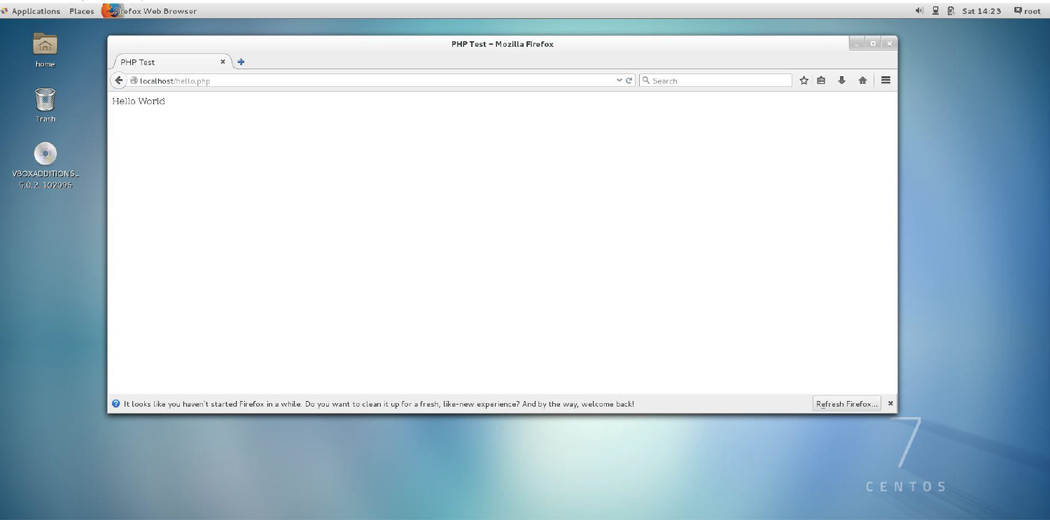

Copy Editor: Bart Reed

Indexer: Ken Johnson

Proofreader: Debbie Williams

Technical Editors: Casey Boyles, Andrew Hurd, Ph.D.

Publishing Coordinator: Vanessa Evans

Designer: Chuti Prasertsith

Composition: Louisa Adair

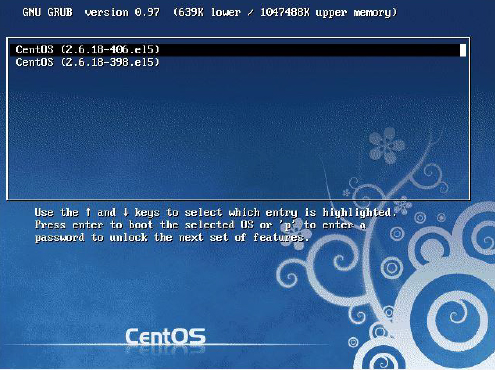

Chapter 1: Distributions and Key Components

Chapter 2: Working on the Command Line

Chapter 5: When Things Go Wrong

Part II: User and Group Accounts

Chapter 6: Managing Group Accounts

Chapter 7: Managing User Accounts

Chapter 8: Develop an Account Security Policy

Part III: File and Data Storage

Chapter 10: Manage Local Storage: Essentials

Chapter 11: Manage Local Storage: Advanced Features

Chapter 12: Manage Network Storage

Chapter 13: Develop a Storage Security Policy

Chapter 16: Common Automation Tasks

Chapter 17: Develop an Automation Security Policy

Chapter 19: Network Configuration

Chapter 20: Network Service Configuration: Essential Services

Chapter 21: Network Service Configuration: Web Services

Chapter 22: Connecting to Remote Systems

Chapter 23: Develop a Network Security Policy

Part VI: Process and Log Administration

Chapter 26: Red Hat–Based Software Management

Chapter 27: Debian-based Software Management

Chapter 29: Develop a Software Management Security Policy

Chapter 32: Intrusion Detection Systems

Chapter 33: Additional Security Tasks

Appendix A: Answers to Review Questions

Index

Chapter 1: Distributions and Key Components

Chapter 2: Working on the Command Line

Chapter 5: When Things Go Wrong

The Science of Troubleshooting

Part II: User and Group Accounts

Chapter 6: Managing Group Accounts

Chapter 7: Managing User Accounts

The Importance of User Accounts

Chapter 8: Develop an Account Security Policy

Part III: File and Data Storage

Chapter 10: Manage Local Storage: Essentials

Chapter 11: Manage Local Storage: Advanced Features

Chapter 12: Manage Network Storage

Chapter 13: Develop a Storage Security Policy

Chapter 16: Common Automation Tasks

Exploring Scripts that Already Exist on Your System

Creating Your Own Automation Scripts

Chapter 17: Develop an Automation Security Policy

Chapter 19: Network Configuration

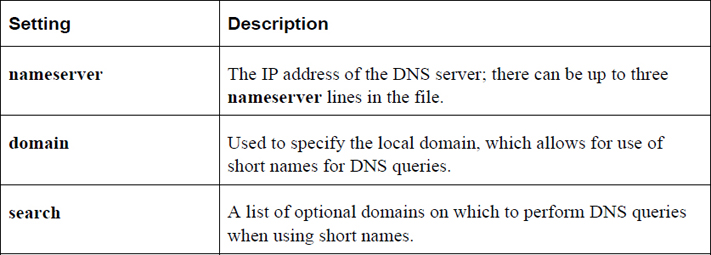

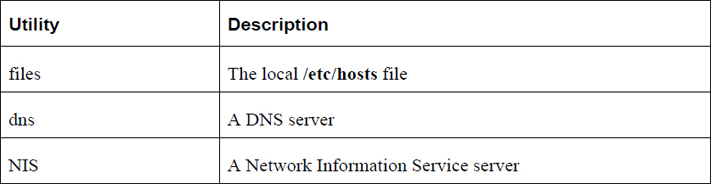

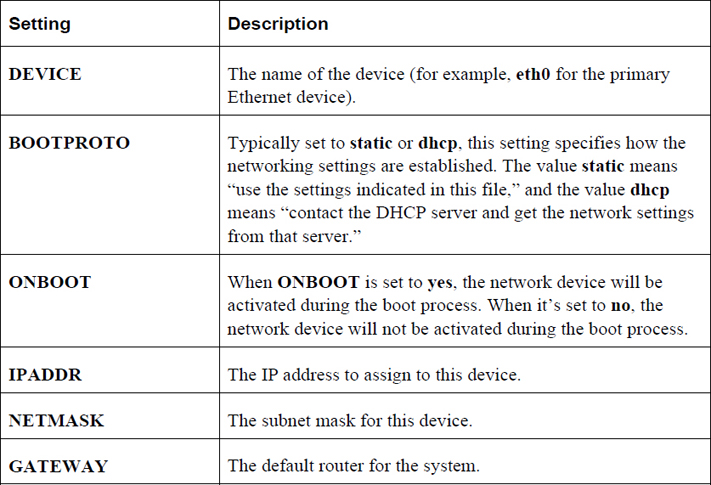

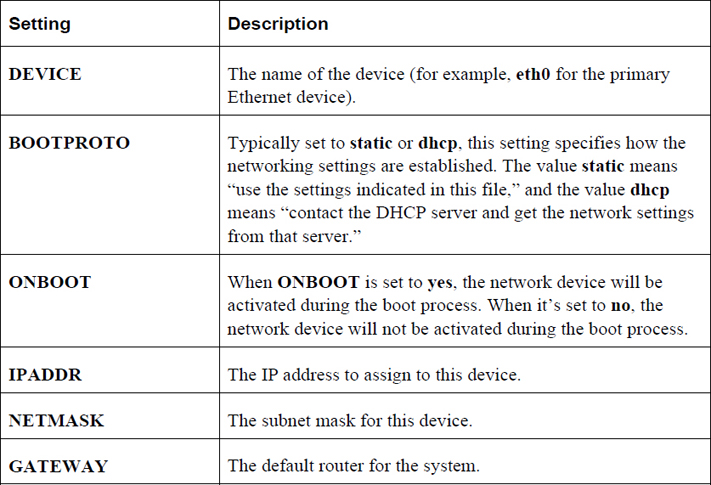

Persistent Network Configurations

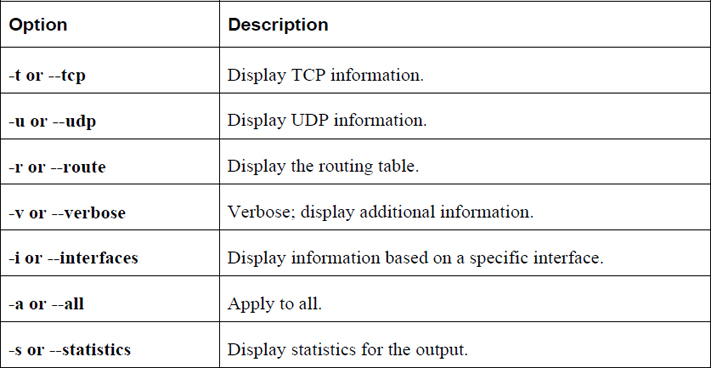

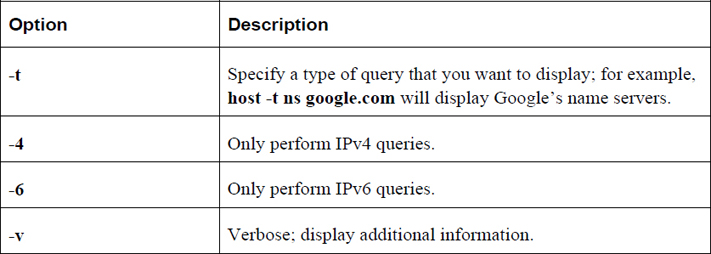

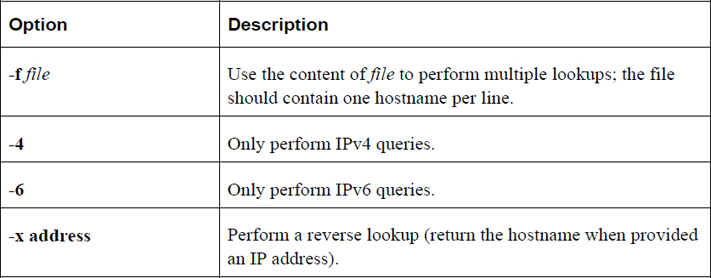

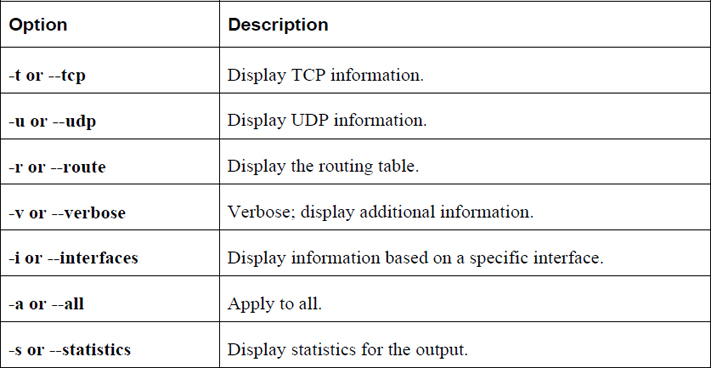

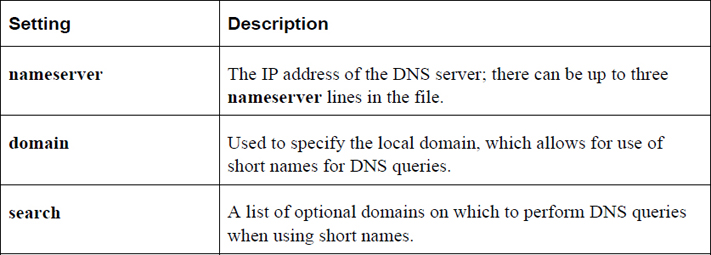

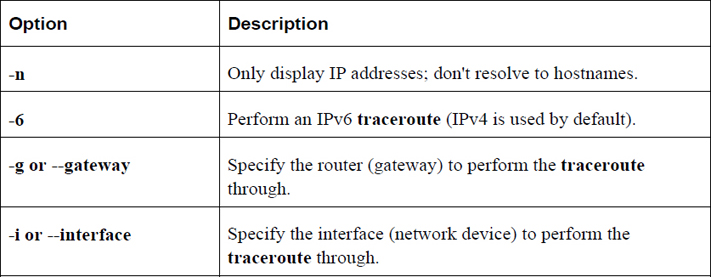

Network Troubleshooting Commands

Chapter 20: Network Service Configuration: Essential Services

Chapter 21: Network Service Configuration: Web Services

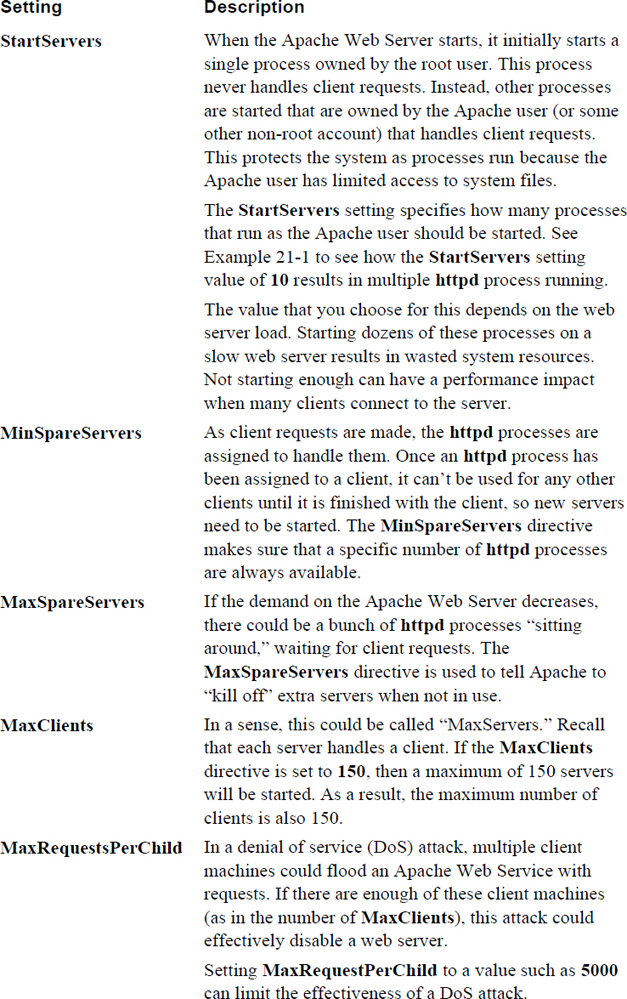

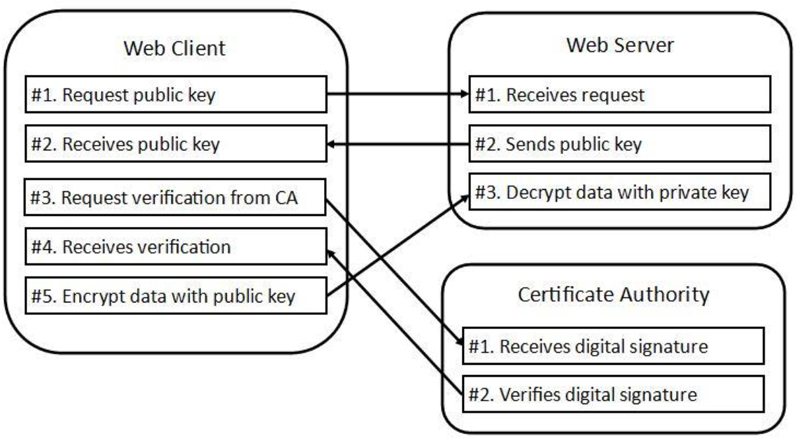

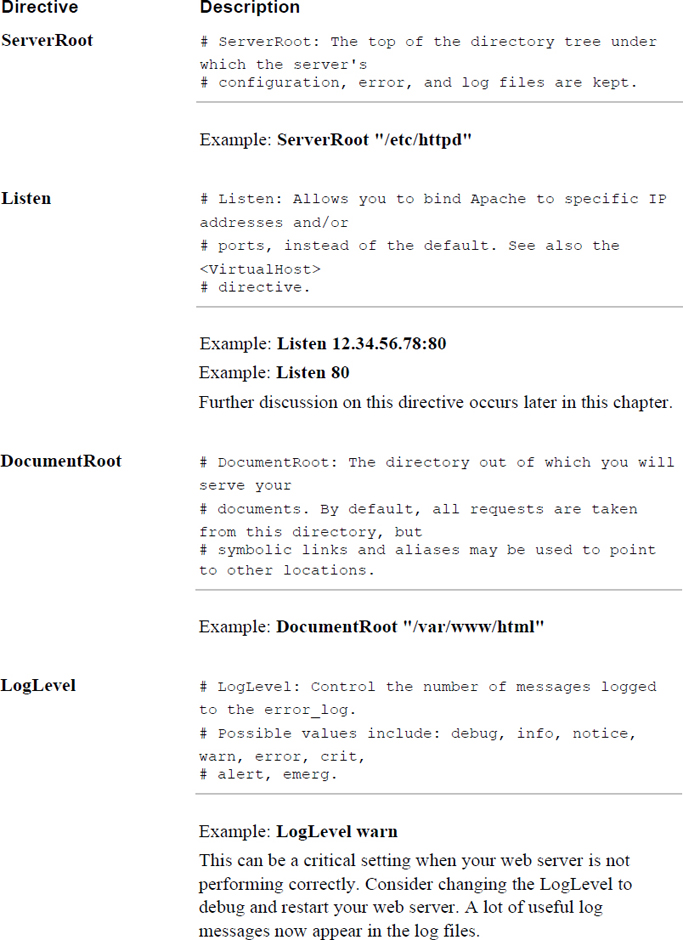

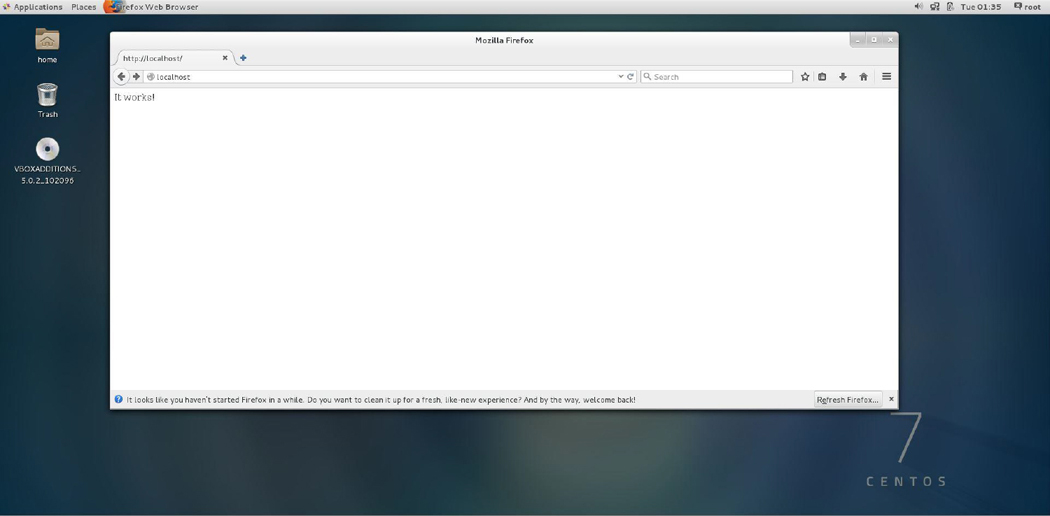

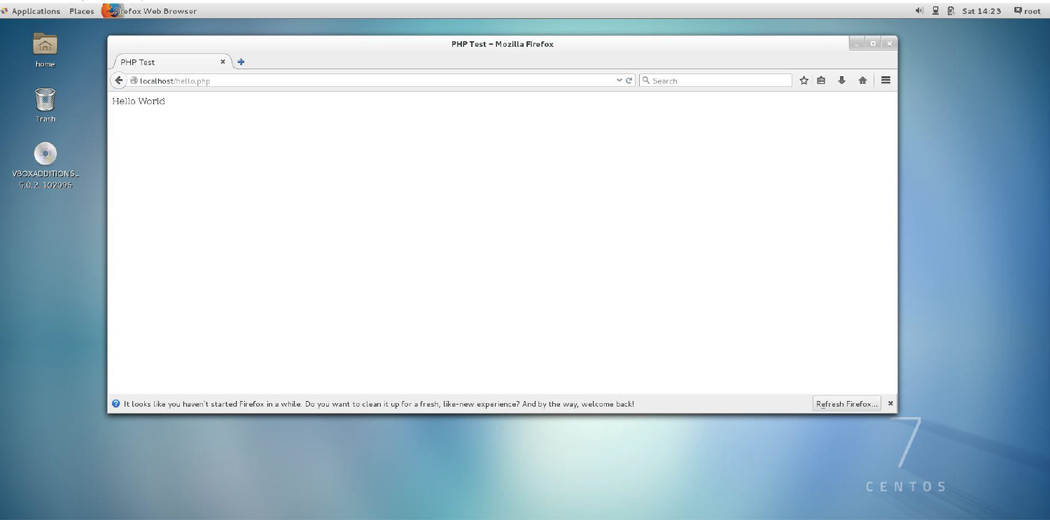

Basic Apache Web Server Configuration

Chapter 22: Connecting to Remote Systems

Chapter 23: Develop a Network Security Policy

Part VI: Process and Log Administration

Chapter 26: Red Hat–Based Software Management

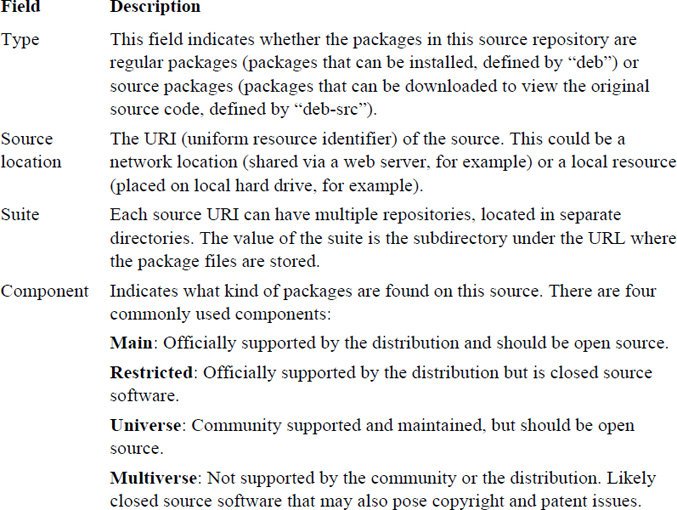

Chapter 27: Debian-Based Software Management

Listing Package Information with APT Commands

Chapter 29: Develop a Software Management Security Policy

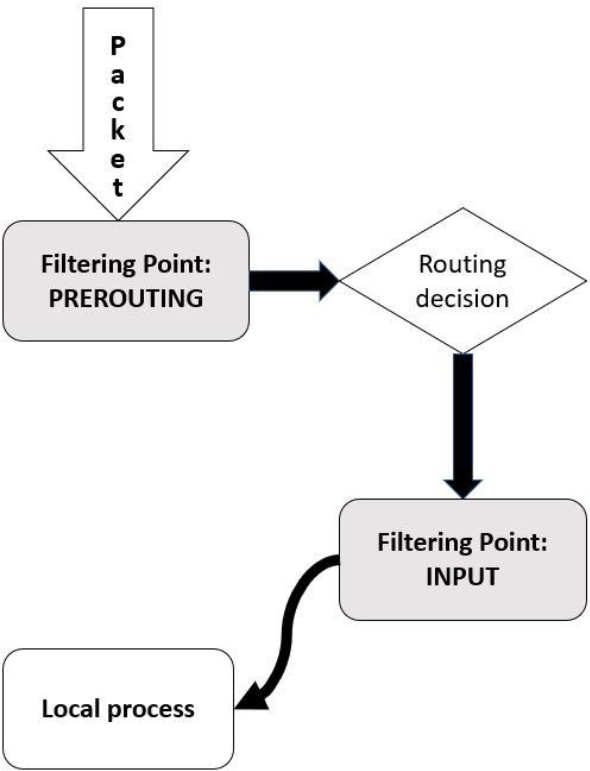

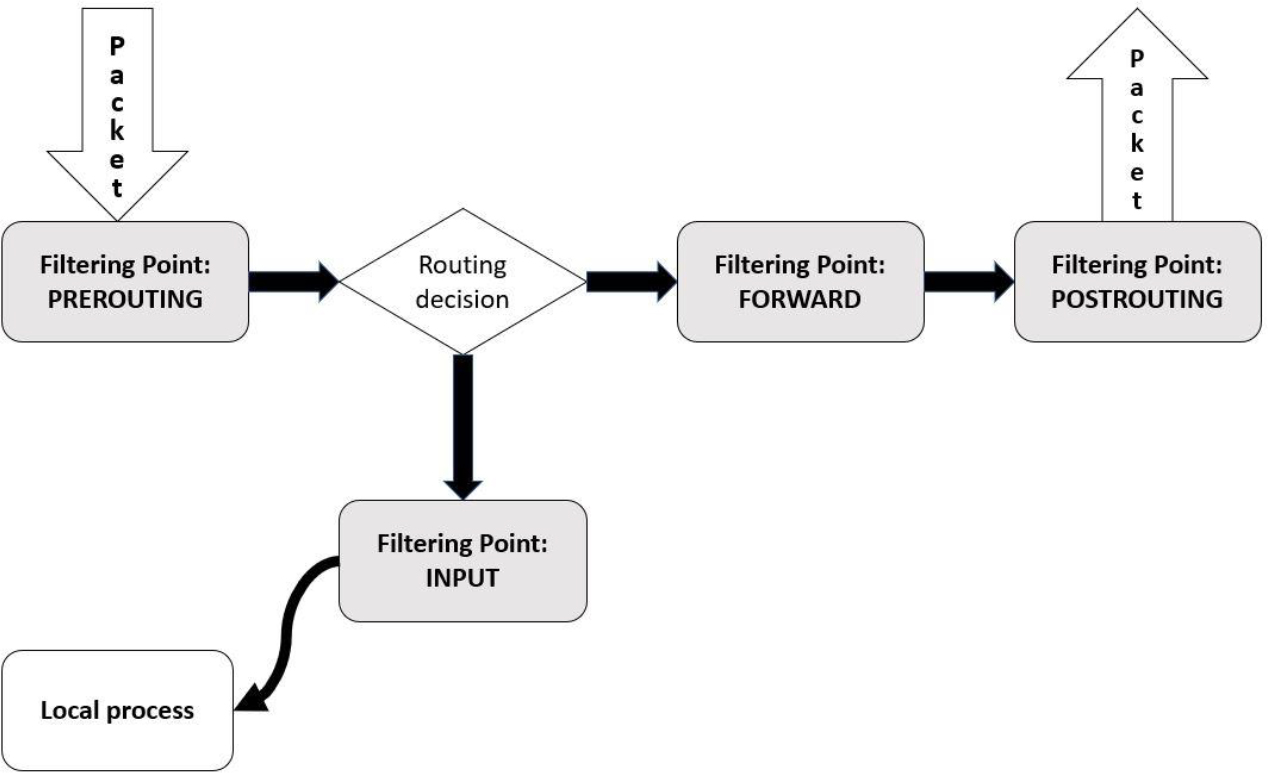

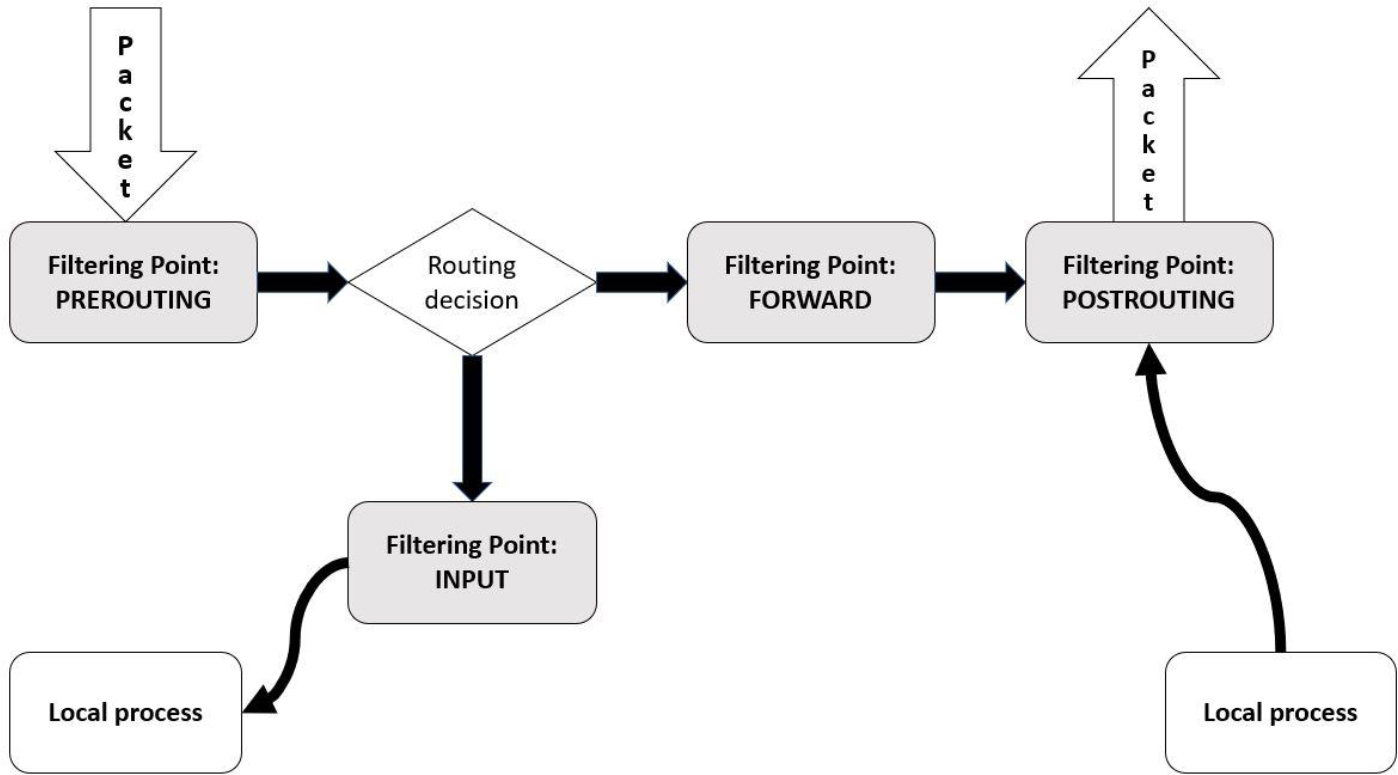

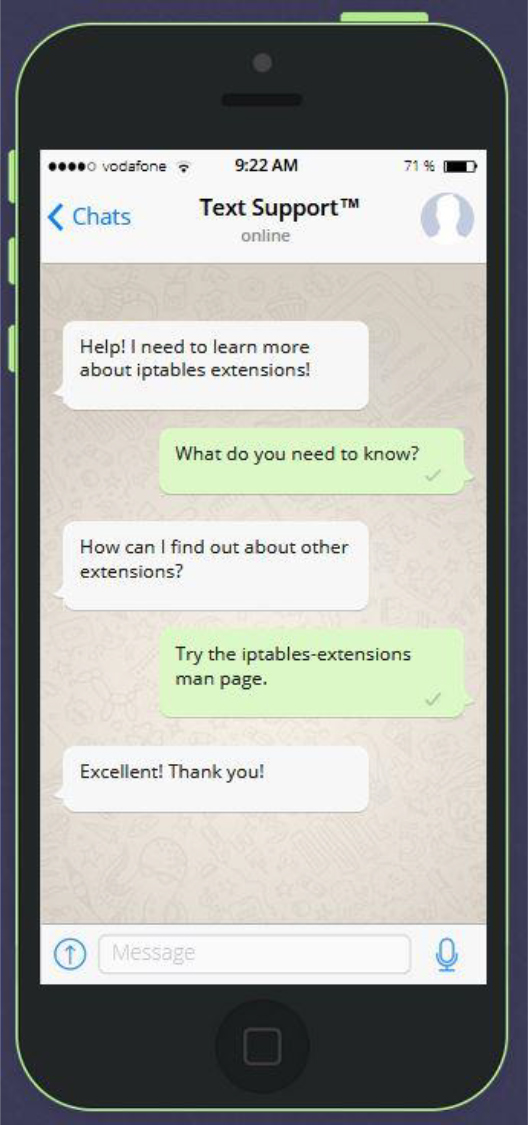

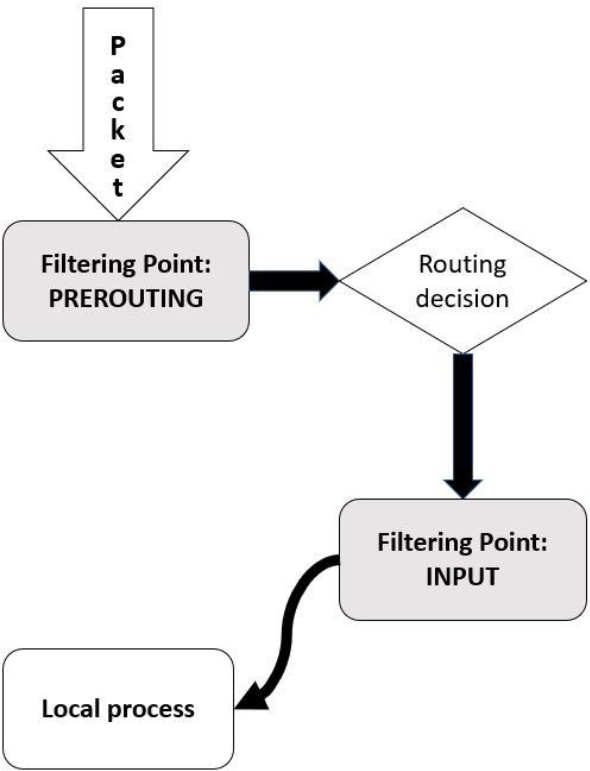

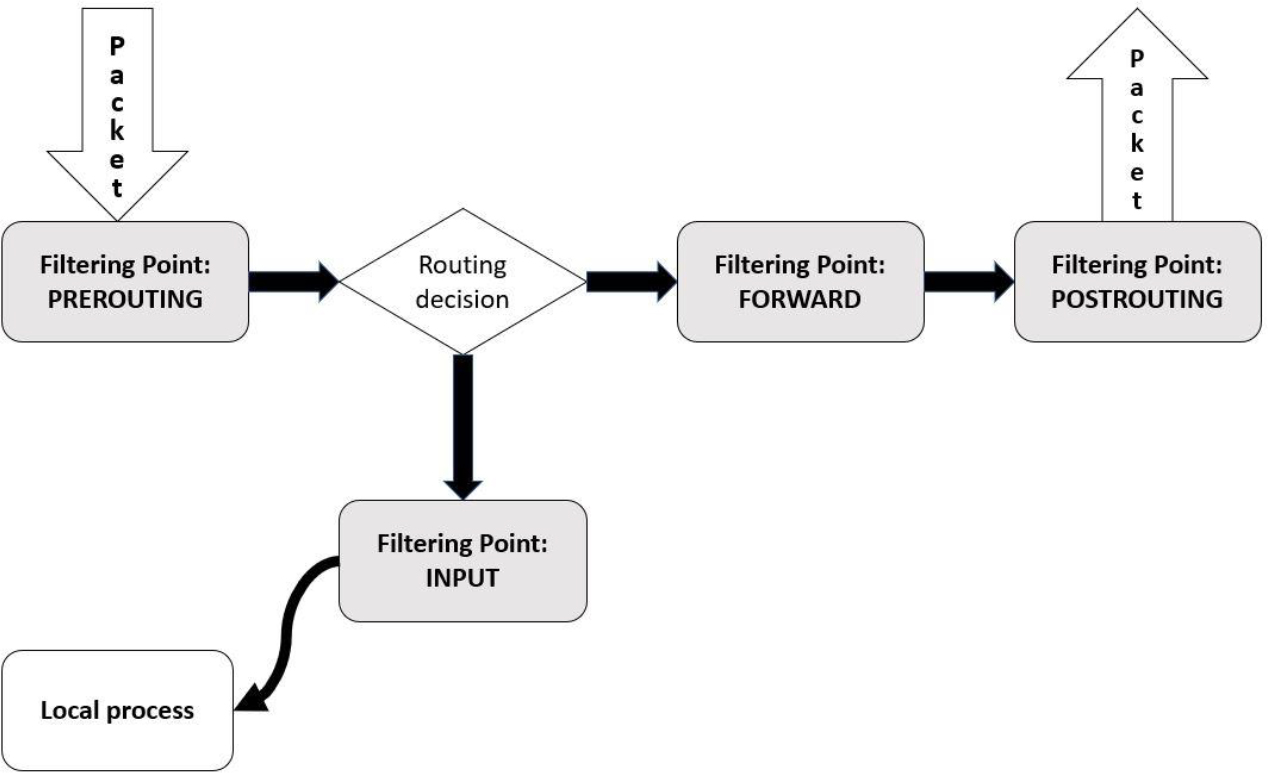

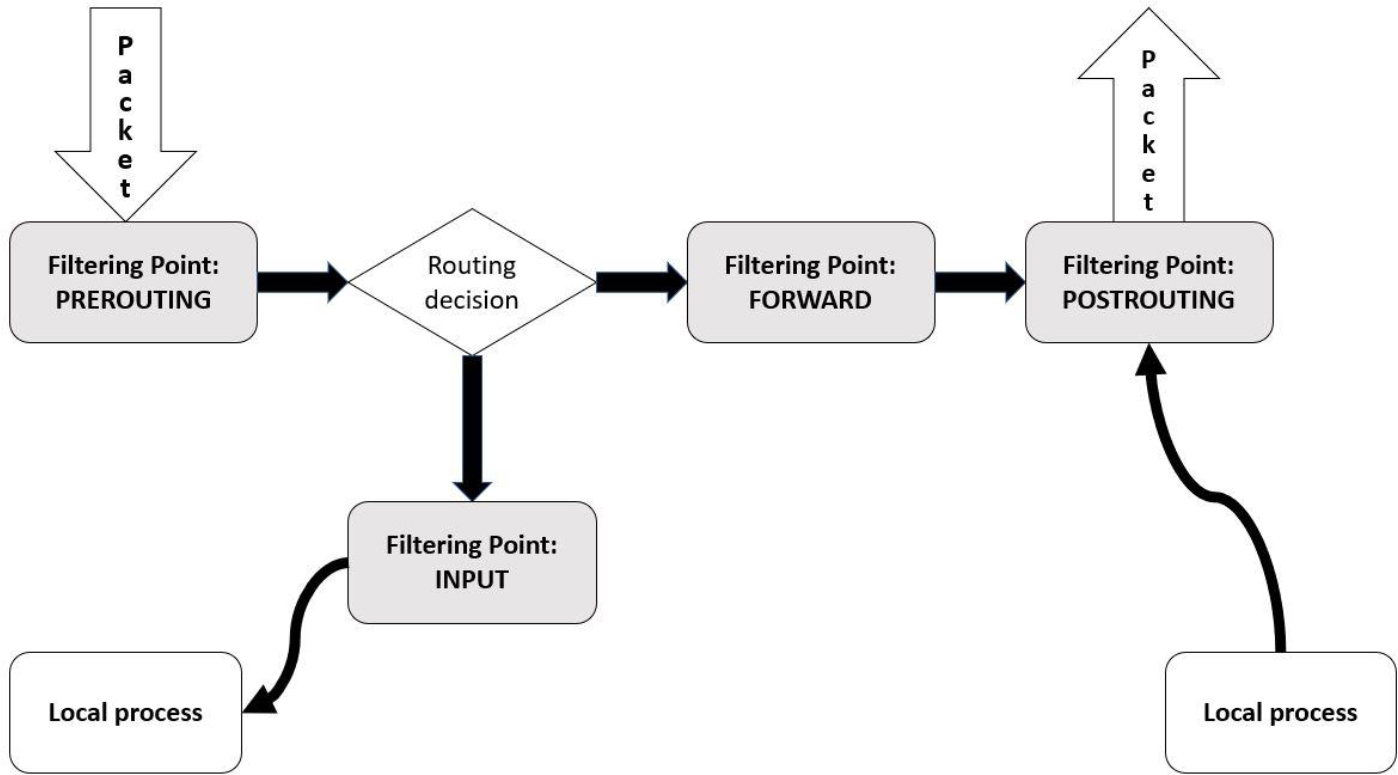

Essentials of the iptables Command

Using iptables to Filter Incoming Packets

Using iptables to Filter Outgoing Packets

Chapter 32: Intrusion Detection

Introduction to Intrusion Detection Tools

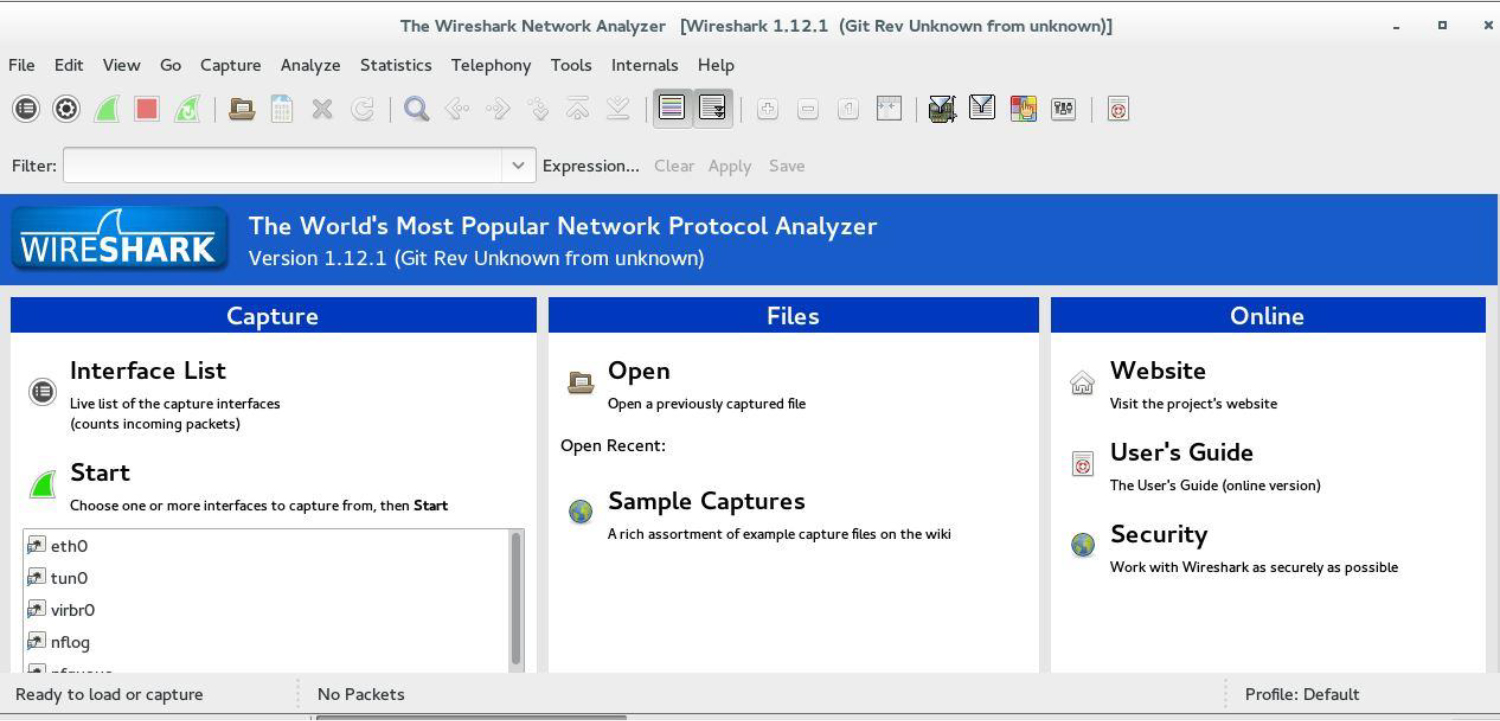

Intrusion Detection Network Tools

Intrusion Detection File Tools

Additional Intrusion Detection Tools

Chapter 33: Additional Security Tasks

William “Bo” Rothwell At the impressionable age of 14, William “Bo” Rothwell crossed paths with a TRS-80 Micro Computer System (affectionately known as a “Trash 80”). Soon after the adults responsible for Bo made the mistake of leaving him alone with the TRS-80, he immediately dismantled it and held his first computer class, showing his friends what made this “computer thing” work.

Since this experience, Bo’s passion for understanding how computers work and sharing this knowledge with others has resulted in a rewarding career in IT training. His experience includes Linux, Unix, and programming languages such as Perl, Python, Tcl, and BASH. He is the founder and president of One Course Source, an IT training organization.

Denise Kinsey, Ph.D, CISSP,C|CISO Dr. Denise Kinsey served as a Unix administrator (HP-UX) in the late 1990s and realized the power and flexibility of the operating system. This appreciation led to her home installation of different flavors of Linux and creation of several academic courses in Linux. With a strong background in cybersecurity, she works to share and implement best practices with her customers and students. Dr. Kinsey is an assistant professor at the University of Houston.

For the last three books, I have thanked my wife and daughter for their patience, and my parents for all that they have done throughout my life. My gratitude continues, as always.

—William “Bo” Rothwell

May 2018

This book is dedicated to…

My family, who inspire and encourage me…

My students, whom I work to inspire and who inspire me…

Those who are interested in Linux and/or cybersecurity. I hope you find the information useful, valuable, and easily applicable.

—Denise Kinsey

Thanks to everyone who has put in a direct effort toward making this book a success:

• Denise, my co-author, for her extremely valuable insight and for dealing with the chaos around my creative process.

• Mary Beth, for putting her trust in me for yet another book.

• Eleanor and Mandie, for keeping me on track (with very gentle reminders) and all of the hard work and dedication.

• Casey and Andrew, for excellent feedback and for proving four brains are better than two.

• Bart Reed, for painsteakingly painstakingly reviewing every word, sentence, graphic, table, and punctuation character.

• And all the other folks at Pearson who have had an impact on this book.

I have always felt that I was fortunate because I had strong technical skills combined with the ability to impart my knowledge to others. This has allowed me to be an IT corporate instructor and courseware developer for almost 25 years now. It is the experiences I have had teaching others that have put me in a position to write a book like this. So, I would also like to acknowledge the following people:

• All of the students who have listen to me for countless hours (I have no idea how you do this). I teach to see the light bulbs go on in your heads. You have taught me patience and given me an understanding that everyone needs to start from some place. Thanks for making me a part of your journey.

• All of the excellent instructors I have observed. There have been so many of them, it would be impossible to list them all here. I’m a much better “knowledge facilitator” because of what I have learned from you.

• Lastly, I have no way to express my gratitude toward people like Linus Torvalds. Without pioneers like Linus (who is one of a great many), so much of the technology we now take for granted just wouldn’t exist. These folks have given us all the opportunity to learn tools that we can use to make even more great inventions. I urge you to not think of Linux as just an operating system, but rather as a building block that allows you and others to create even more amazing things.

—William “Bo” Rothwell

May, 2018

Thank you to all who made this book a reality—from Mary Beth and everyone at Pearson Education, to the technical editors for their time and detailed reviews.

Also, thanks to the many wonderful faculty in cybersecurity who share their knowledge freely and offer their assistance—from the design of virtual networks to the design of curriculum. This includes the many wonderful people at the Colloquia for Information Systems Security Education (CISSE), the Center for System Security and Information Security (CSSIA), and the National CyberWatch Center. The resources provided by these organizations are wonderful and a great place to start for anyone looking to build cybersecurity programs.

Finally, I wish to thank my co-workers W. “Art” Conklin and R. “Chris” Bronk. I appreciate your guidance in the world of academia and suggestions for research.

—Denise Kinsey

Casey Boyles developed a passion for computers at a young age, and started working in the IT field over 25 years ago. He quickly moved on to distributed applications and database development. Casey later moved on to technical training and learning development, where he specializes in full stack Internet application development, database architecture, and systems security. Casey typically spends his time hiking, boxing, or smoking cigars while “reading stuff and writing stuff.”

Andrew Hurd is the Technical Program Facilitator of Cybersecurity for Southern New Hampshire University. Andrew is responsible for curriculum development and cyber competition teams. He holds a dual Bachelor of Arts in computer science and mathematics, a masters in the science of teaching mathematics, and a Ph.D. in information sciences, specializing in information assurance and online learning. Andrew, the author of a Network Guide to Security+ lab manual and Cengage, has over 17 years as a higher education professor.

As the reader of this book, you are our most important critic and commentator. We value your opinion and want to know what we’re doing right, what we could do better, what areas you’d like to see us publish in, and any other words of wisdom you’re willing to pass our way.

We welcome your comments. You can email or write to let us know what you did or didn’t like about this book—as well as what we can do to make our books better.

Please note that we cannot help you with technical problems related to the topic of this book.

When you write, please be sure to include this book’s title and author as well as your name and email address. We will carefully review your comments and share them with the author and editors who worked on the book.

Email: feedback@pearsonitcertification.com

Mail: Pearson IT Certification

ATTN: Reader Feedback

800 East 96th Street

Indianapolis, IN 46240 USA

Visit our website and register this book at www.pearsonitcertification.com/register for convenient access to any updates, downloads, or errata that might be available for this book.

Introduced as a hobby project in 1991, Linux has become a dominate player in the IT market today. Although technically Linux refers to a specific software piece (the kernel), many people refer to Linux as a collection of software tools that make up a robust operating system.

Linux is a heavily used technology throughout the IT industry, and it is used as an alternative to more common platforms because of its security, low cost, and scalability. The Linux OS is used to power a larger variety of servers, including email and web servers. Additionally, it is often favored by software developers as the platform they code on.

As with any operating system, cybersecurity should be a major concern for any IT professional who works on a Linux system. Because of the large variety of software running on a Linux system, as well as several different versions of Linux (called distributions), cybersecurity can be a complicated process that involves both system users and system administrators.

Regretfully, cybersecurity is often overlooked in books and classes on Linux. Typically, these forms of learning tend to focus on how to use the Linux system, and cybersecurity is often mentioned as an afterthought or considered an advanced topic for highly experience professionals. This could be because the authors of these books and classes feel that cybersecurity is a difficult topic to learn, but ignoring this topic when discussing Linux is a huge mistake.

Why is cybersecurity such an important topic when learning Linux? One reason is that Linux is a true multiuser operating system. This means that even regular users (end users) need to know how to keep their own data secure from other users.

Another reason why cybersecurity is critical is because most Linux operating systems provide a great number of network-based services that are often exposed to the Internet. The prying eyes of millions of people worldwide need to be considered when securing a personal Linux system or the Linux systems for an entire organization.

Our goal with this book is to provide you with the skills a Linux professional should have. The approach we take is a typical “ground-up” approach, but with the unique methodology of always keeping an eye on security. Throughout this book, you will find references to security issues. Entire sections are devoted to security, and a strong emphasis is placed on creating security policies.

Linux is a very large topic, and it is really impossible to cover it entirely in one book. The same is true regarding Linux security. We have made every effort to provide as much detail as possible, but we also encourage you to explore on your own to learn more about each topic introduced in this book.

Thank you, and enjoy your Linux cybersecurity journey.

It might be easier to answer the question “who shouldn’t read this book?” Linux distributions are used by a large variety of individuals, including:

• Software developers.

• Database administrators.

• Website administrators.

• Security administrators.

• System administrators.

• System recovery experts.

• “Big data” engineers.

• Hackers.

• Governmental organizations.

• Mobile users and developers. (Android is a Linux distribution.)

• Chip vendors. (Embedded Linux is found on many chip devices.)

• Digital forensic experts.

• Educators.

The previous list isn’t even a complete list! Linux is literally everywhere. It is the OS used on Android phones. A large number of web and email servers run on Linux. Many network devices, such as routers and firewalls, have a version of embedded Linux installed on them.

This book is for people who want to better use Linux systems and ensure that the Linux systems that they work on are as secure as possible.

Chapter 1, “Distributions and Key Components,” dives into essential information related to understanding the various parts of Linux. You learn about the different components of the Linux operating system, as well as what a distribution is. You also learn how to install the Linux operating system.

Chapter 2, “Working on the Command Line,” covers the essential commands needed to work within the Linux environment.

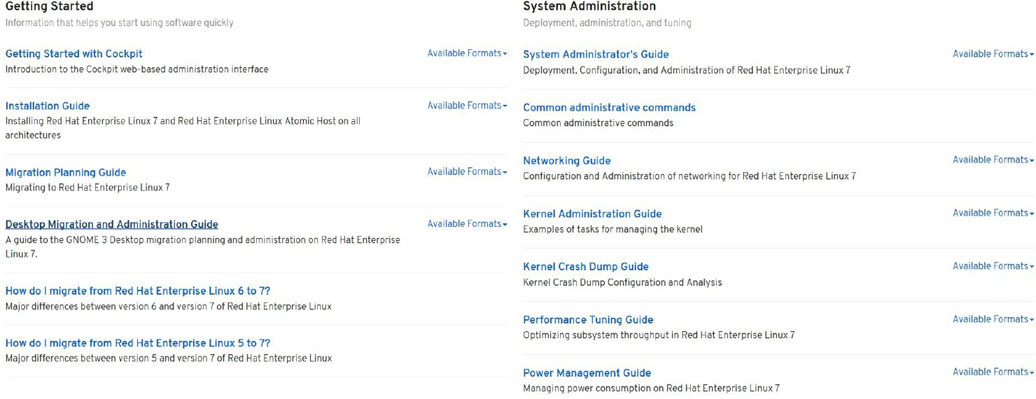

Chapter 3, “Getting Help,” provides you with the means to get additional information on Linux topics. This includes documentation that is natively available on the operating system as well as important web-based resources.

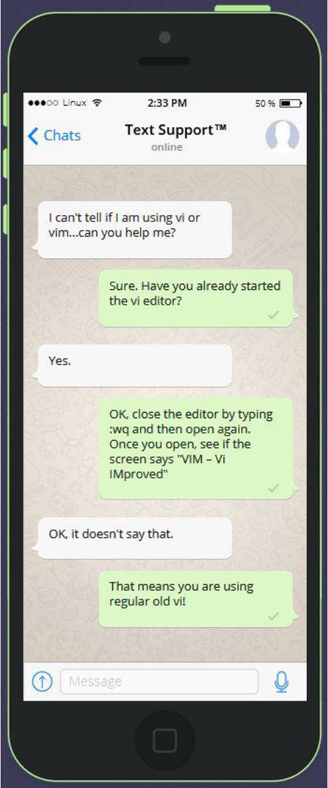

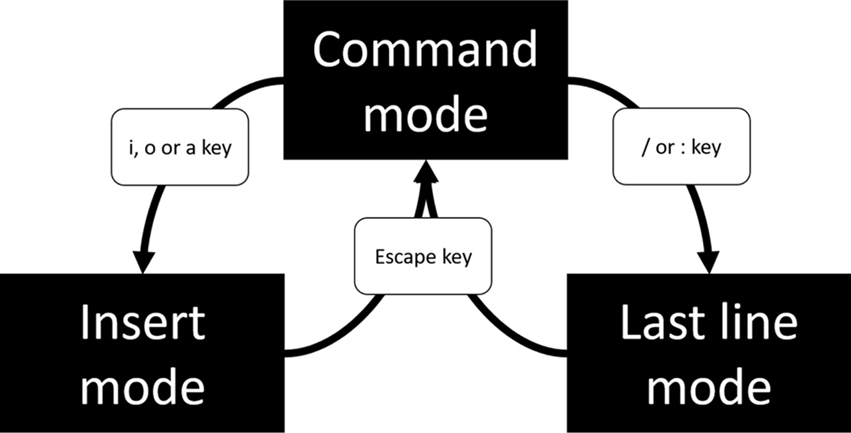

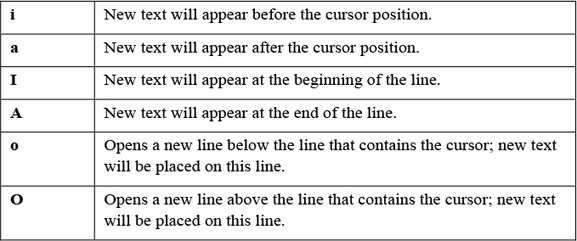

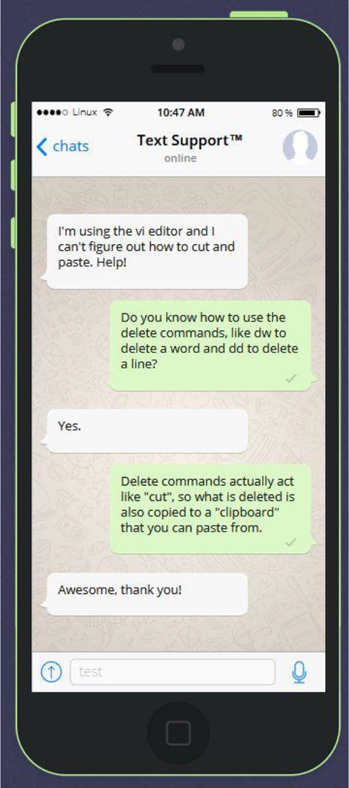

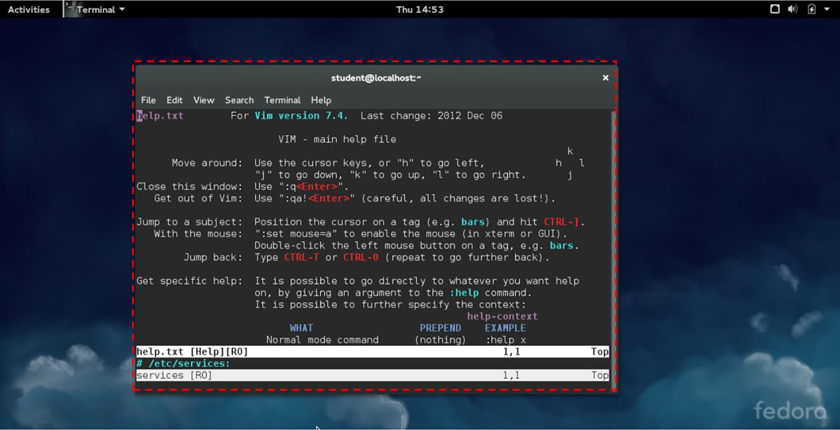

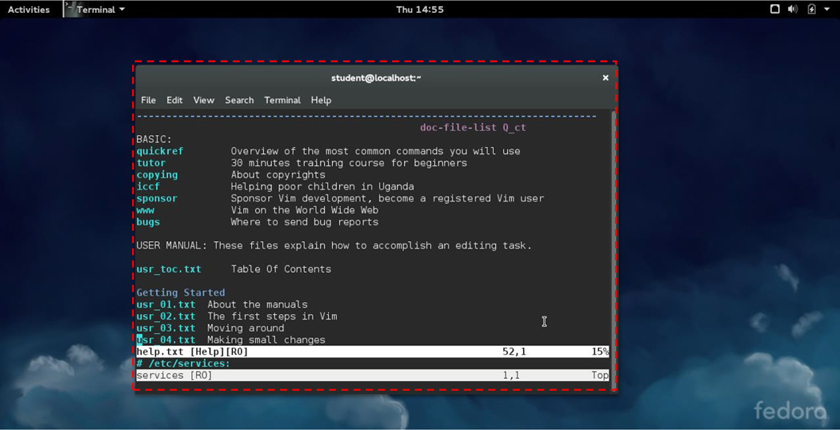

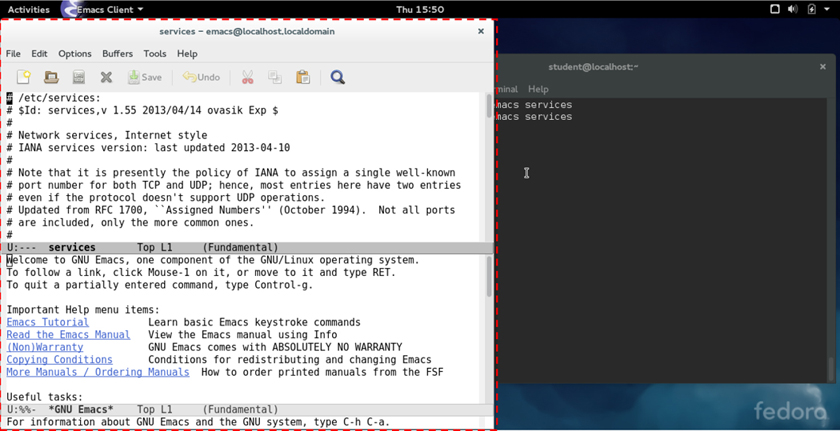

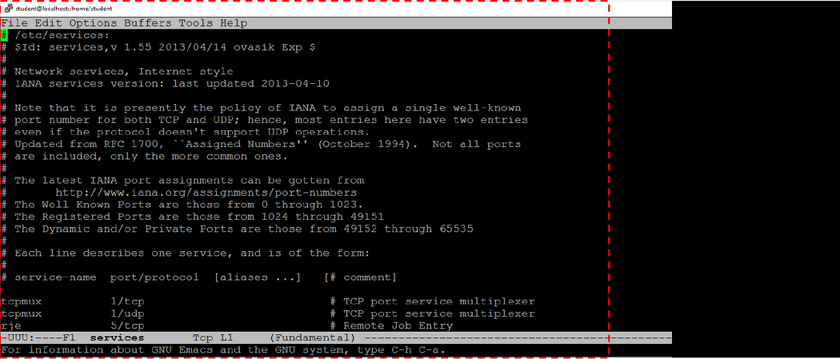

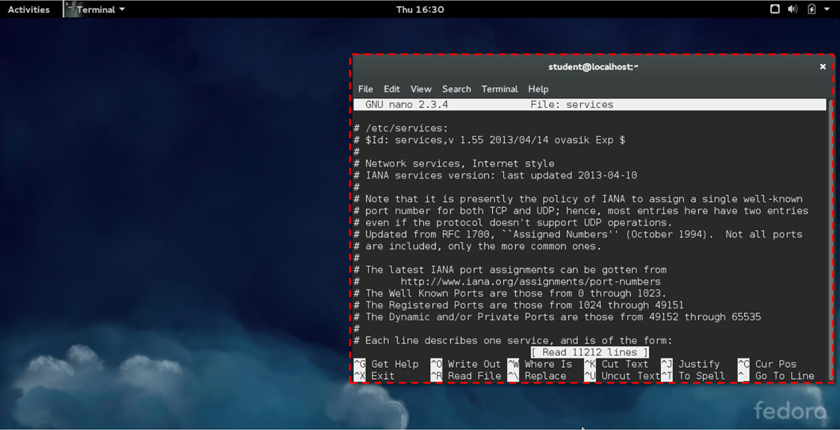

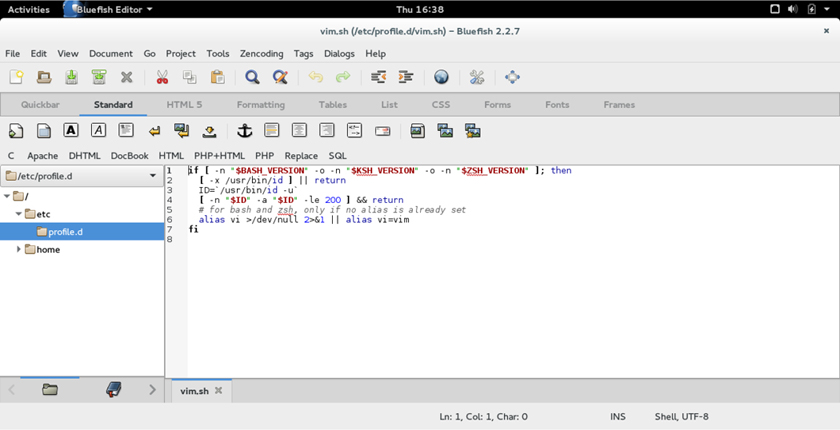

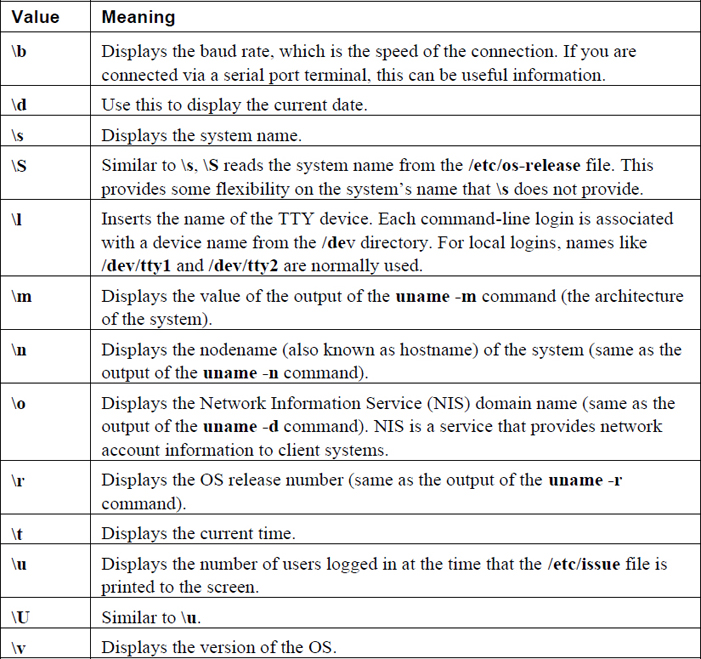

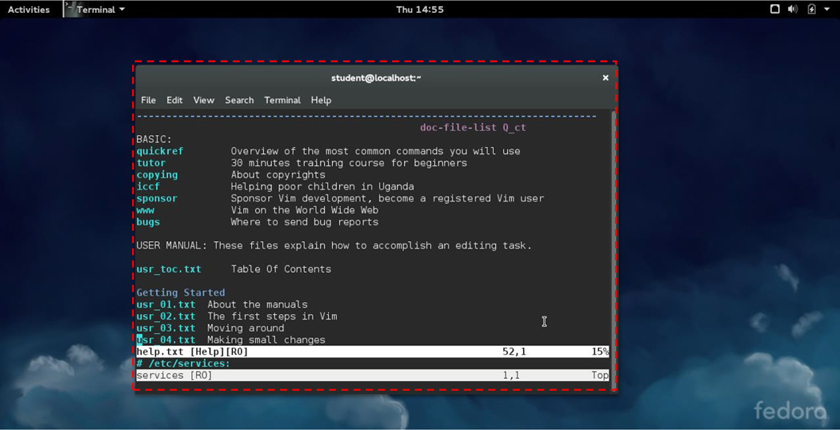

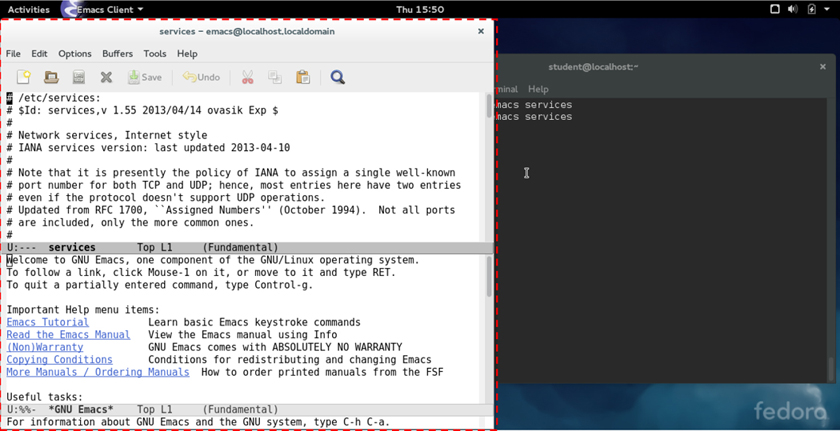

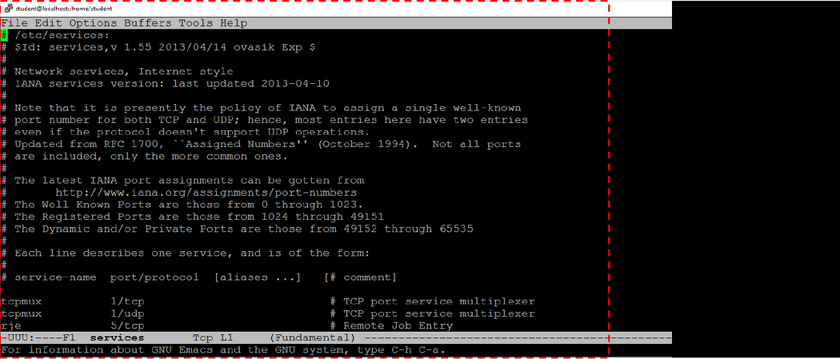

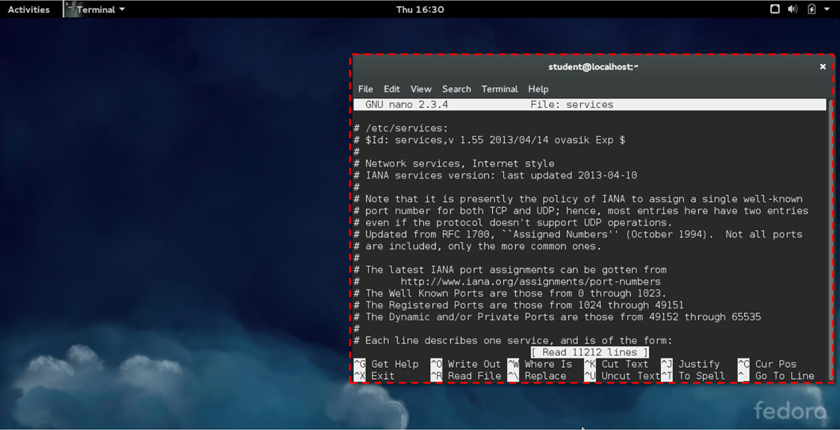

Chapter 4, “Editing Files,” focuses on utilities that you can use to edit text files. Editing text files is a critical Linux task because much of the configuration data is stored in text files.

Chapter 5, “When Things Go Wrong,” reviews how to handle problems that may arise in Linux. This chapter provides details on how to troubleshoot system problems within a Linux environment.

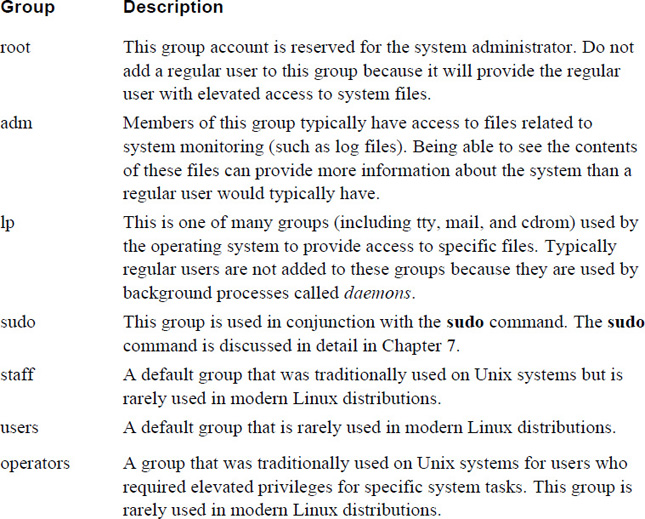

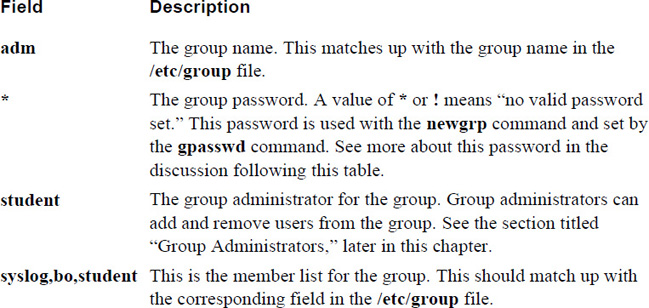

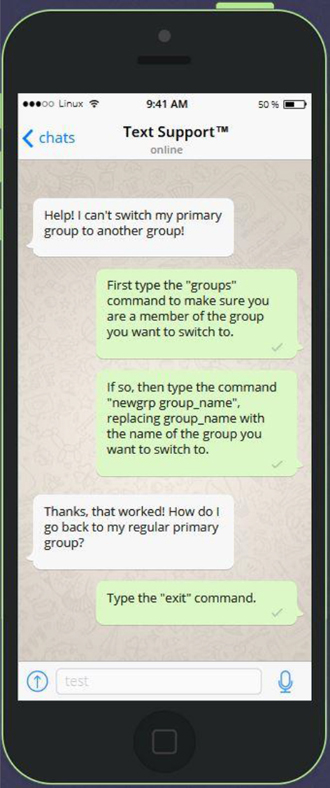

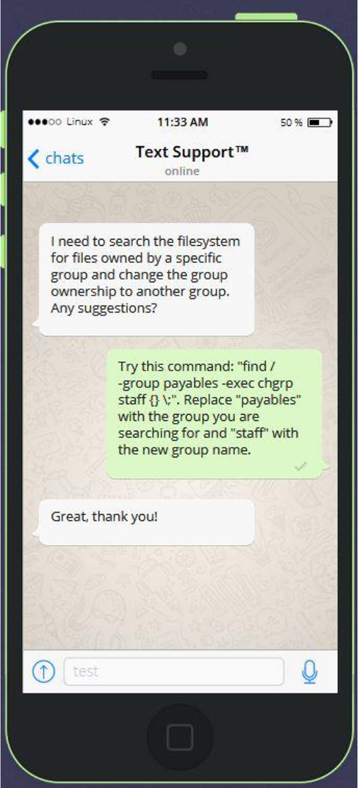

Chapter 6, “Managing Group Accounts,” focuses on group accounts, including how to add, modify, and delete groups. Special attention is placed on system (or special) groups as well as understanding the difference between primary and secondary groups.

Chapter 7, “Managing User Accounts,” covers the details regarding user accounts. You learn how to create and secure these account, as well as how to teach users good security practices in regard to protecting their accounts.

Chapter 8, “Develop an Account Security Policy,” provides you with the means to create a security policy using the knowledge you acquired in Chapters 6 and 7.

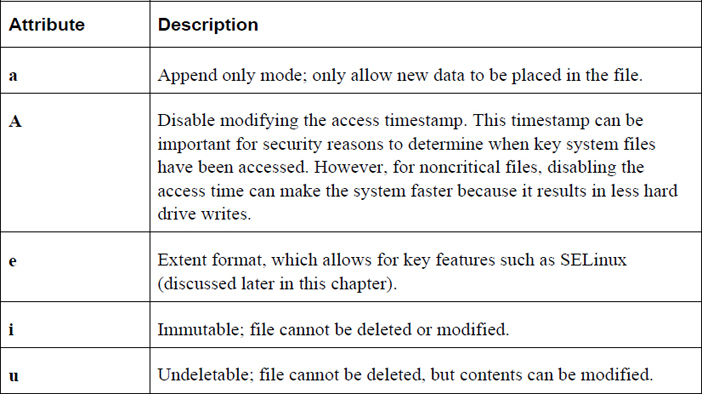

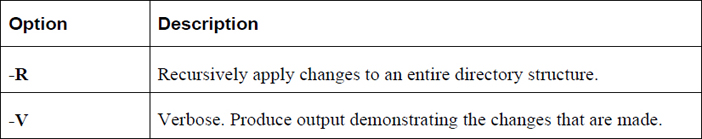

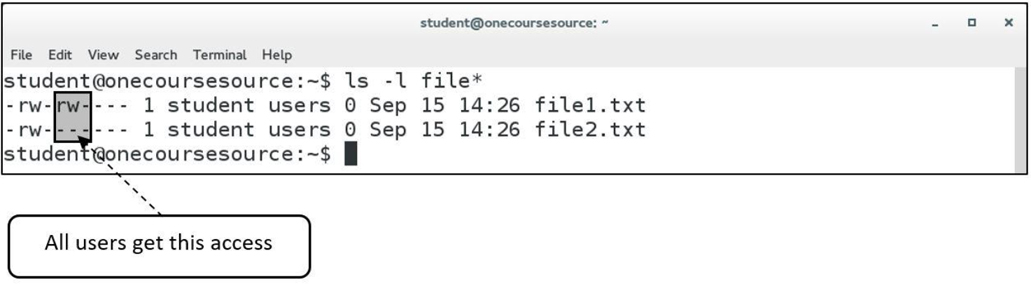

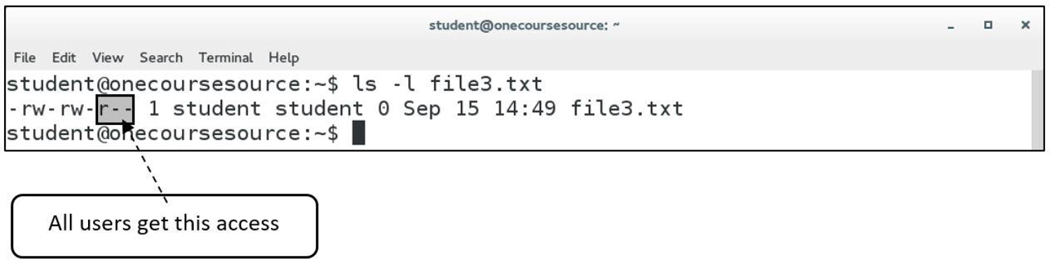

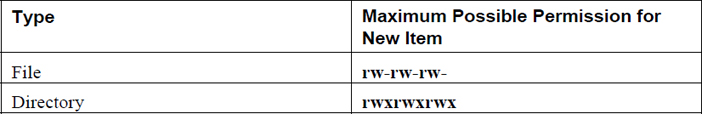

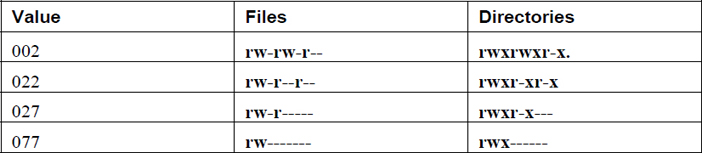

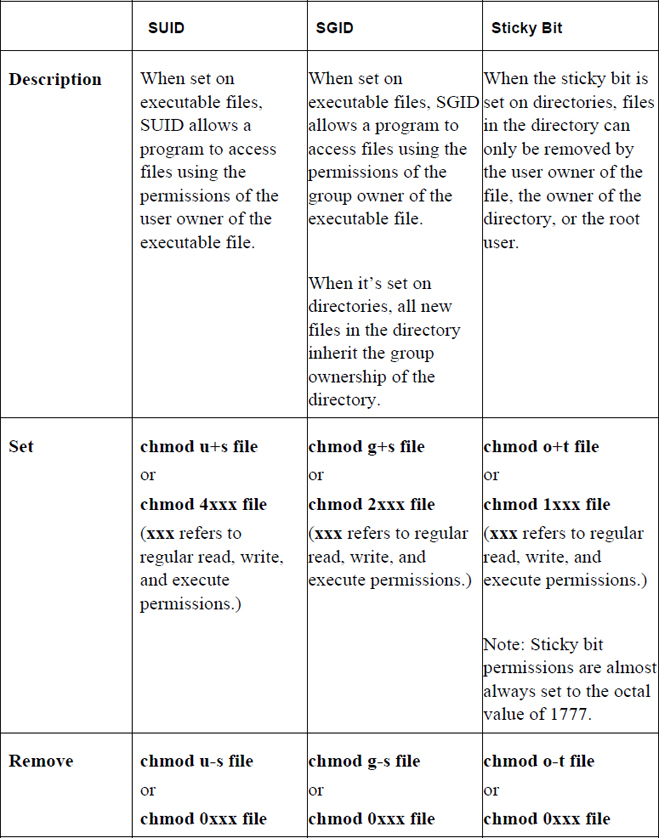

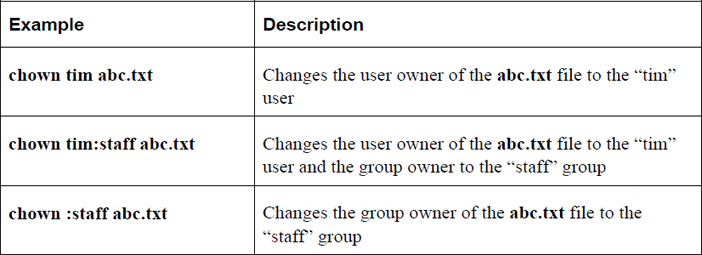

Chapter 9, “File Permissions,” focuses on securing files using Linux permissions. This chapter also dives into more advanced topics, such as special permissions, the umask, access control lists (ACLs), and file attributes.

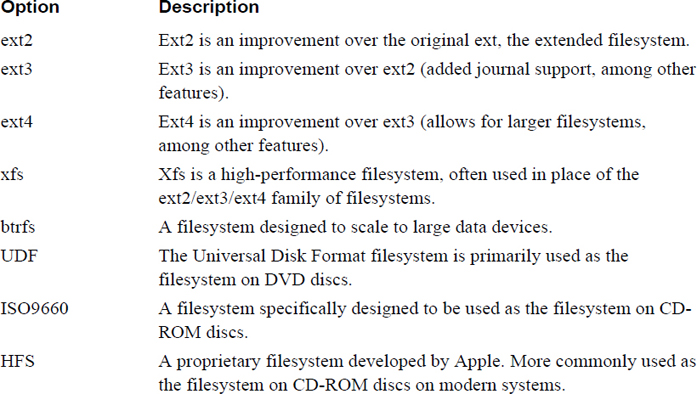

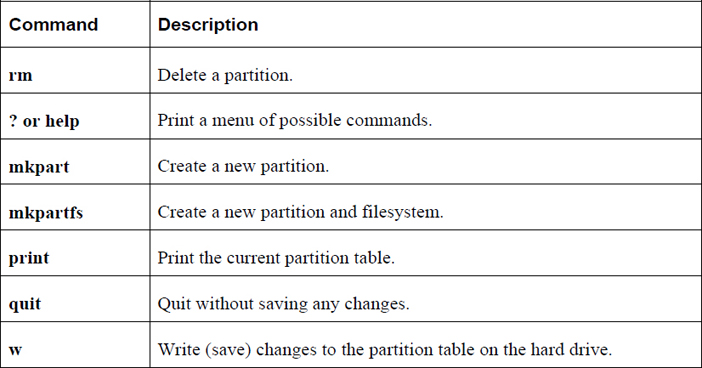

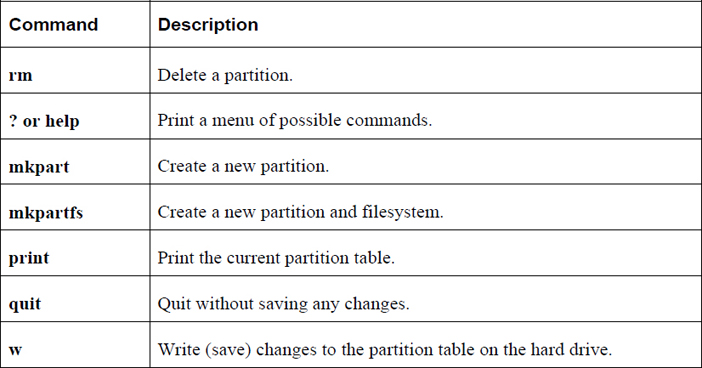

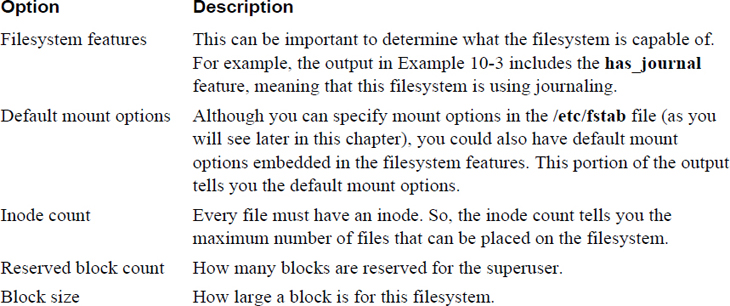

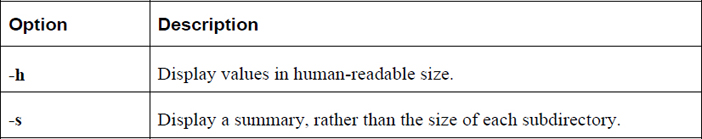

Chapter 10, “Manage Local Storage: Essentials,” covers topics related to the concepts of local storage devices. This includes how to create partitions and filesystems, as well as some additional essential filesystem features.

Chapter 11, “Manage Local Storage: Advanced Features,” covers topics related to advanced features of local storage devices. This includes how to use autofs and create encrypted filesystems. You also learn about logical volume management, an alternative way of managing local storage devices

Chapter 12, “Manage Network Storage,” discusses making storage devices available across the network. Filesystem sharing techniques such as Network File System, Samba, and iSCSI are also included.

Chapter 13, “Develop a Storage Security Policy,” provides you with the means to create a security policy using the knowledge you acquire in Chapters 9–12.

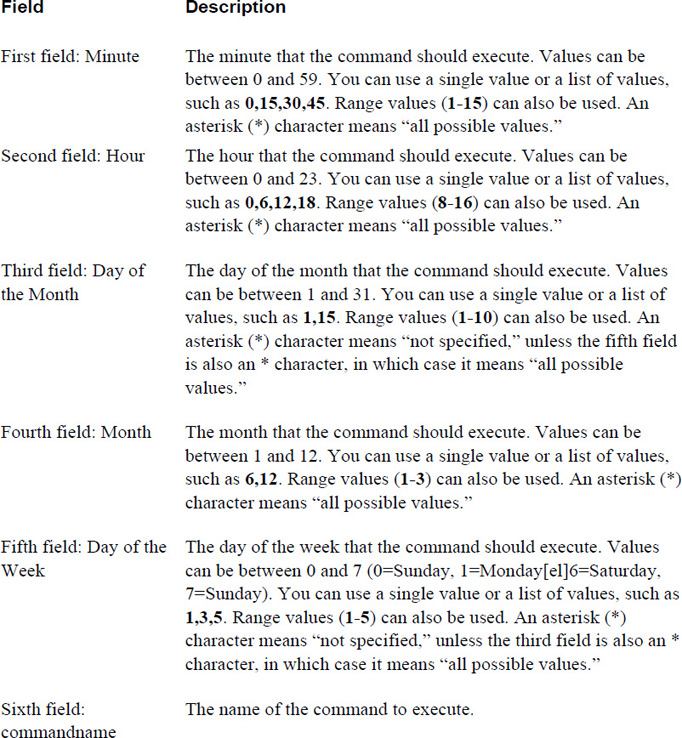

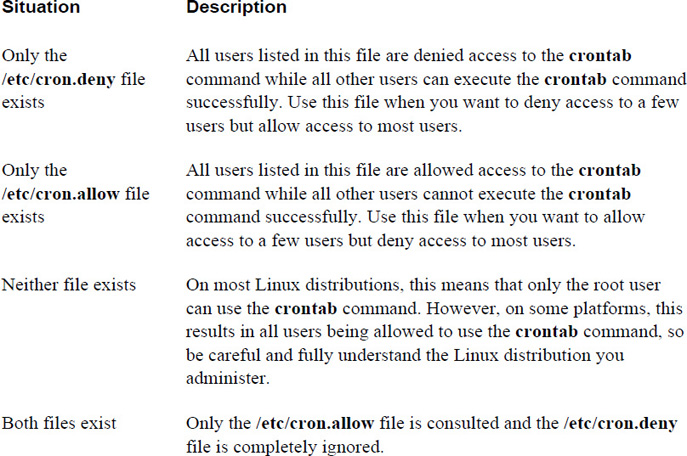

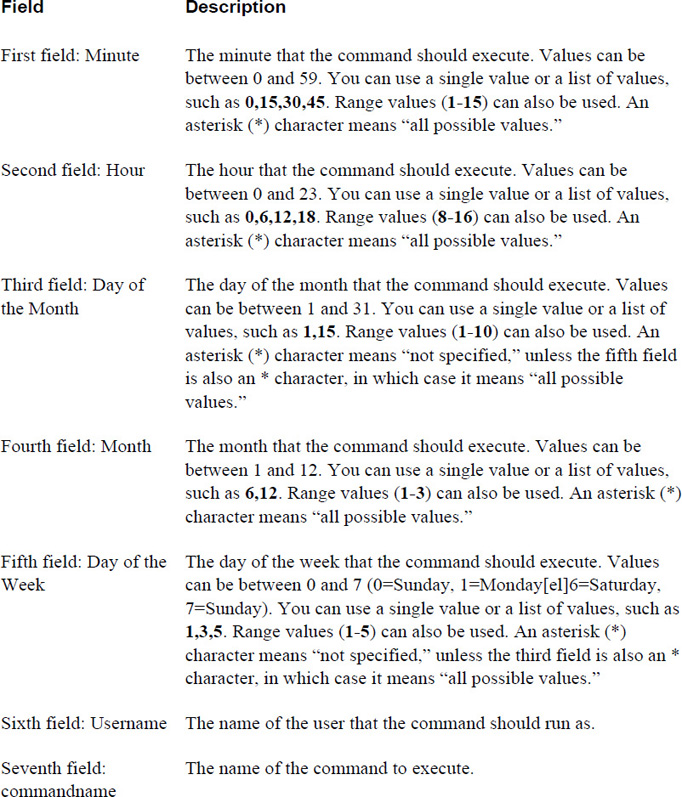

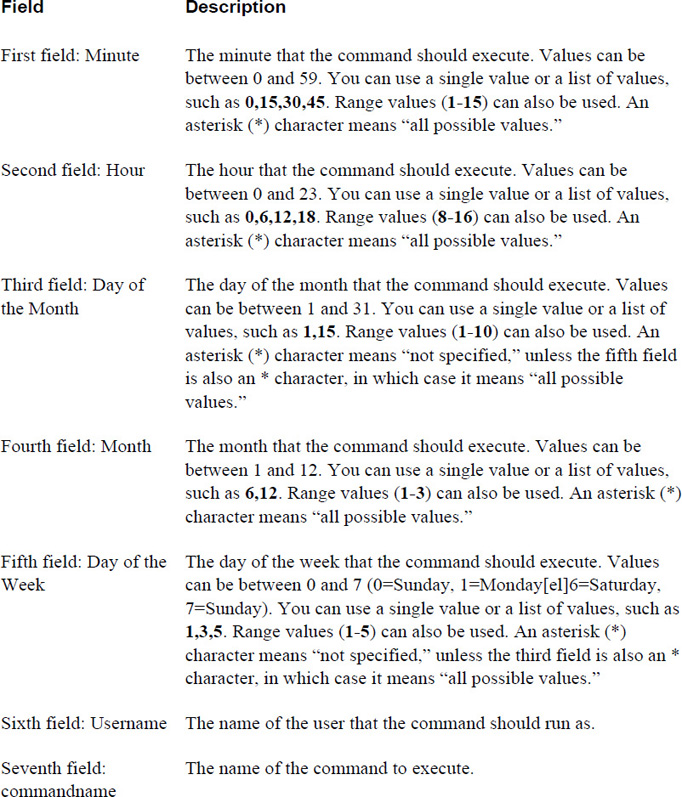

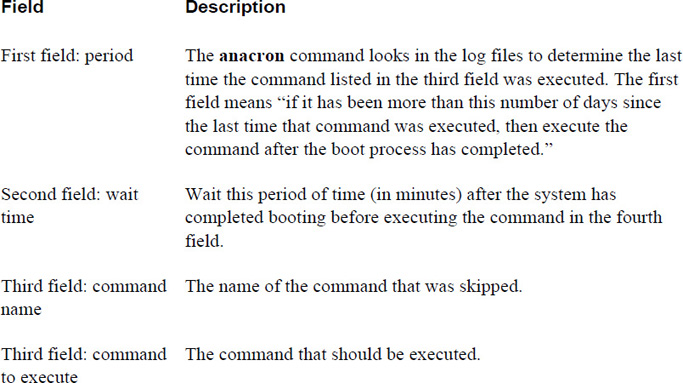

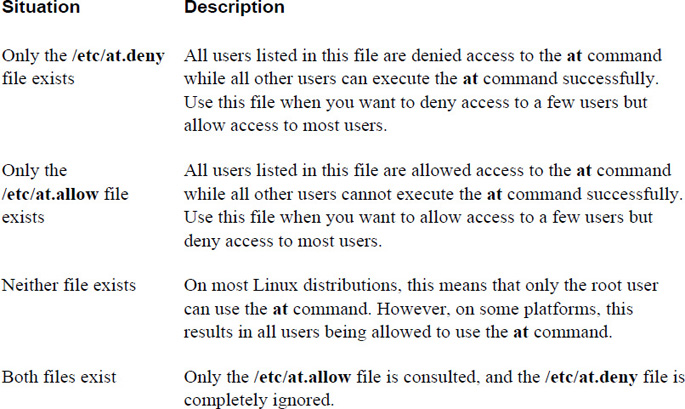

Chapter 14, “Crontab and At,” covers two sets of tools that allow you to automatically execute processes at future times. The crontab system allows users to execute programs at regular intervals, such as once a month or twice a week. The at system provides users with a way to execute a program at one specific time in the future.

Chapter 15, “Scripting,” covers the basics of placing BASH commands into a file in order to create a more complex set of commands. Scripting is also useful for storing instructions that may be needed at a later time.

Chapter 16, “Common Automation Tasks,” covers the sort of tasks that both regular users and system administrators routinely automate. The focus of this chapter is on security, but additional automation tasks are demonstrated, particularly those related to topics that were covered in previous chapters.

Chapter 17, “Develop an Automation Security Policy,” provides you with the means to create a security policy using the knowledge you acquire in Chapters 14–16.

Chapter 18, “Networking Basics,” covers the essentials you should know before configuring and securing your network connections.

Chapter 19, “Network Configuration,” covers the process of configuring your system to connect to the network.

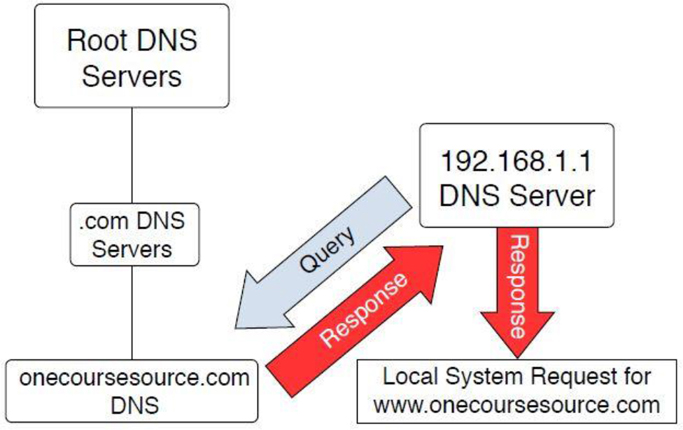

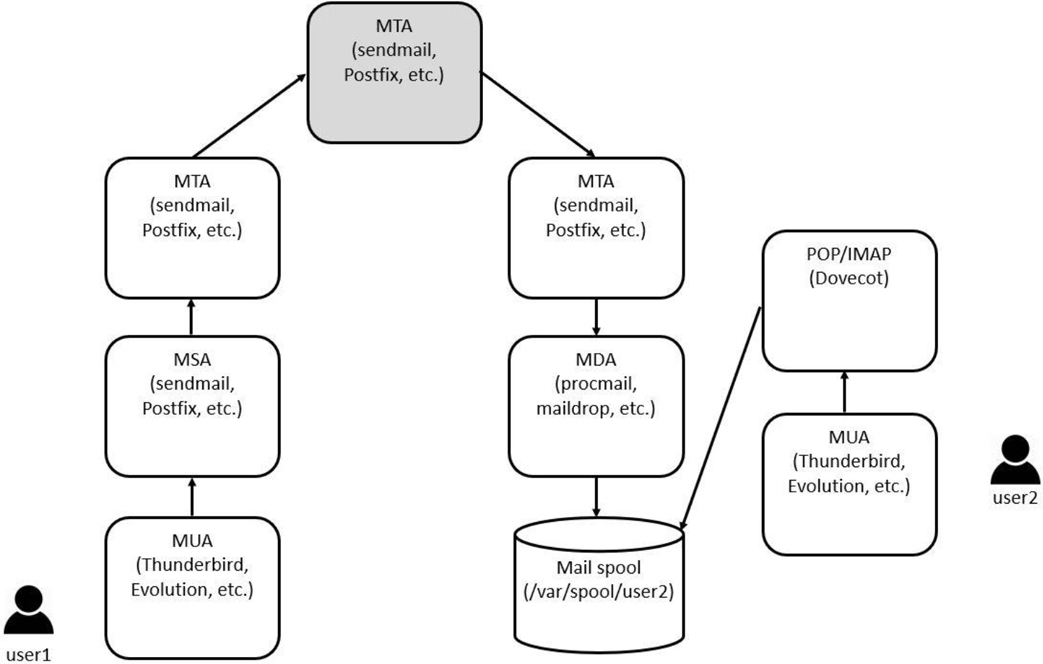

Chapter 20, “Network Service Configuration: Essential Services,” covers the process of configuring several network-based tools, including DNS, DHCP, and email servers.

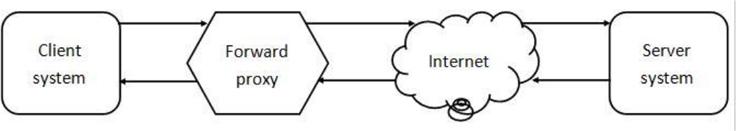

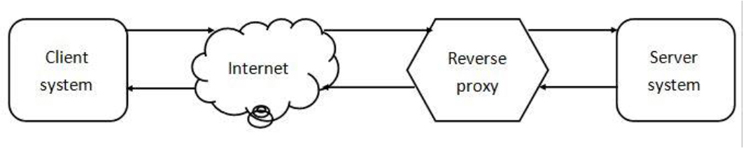

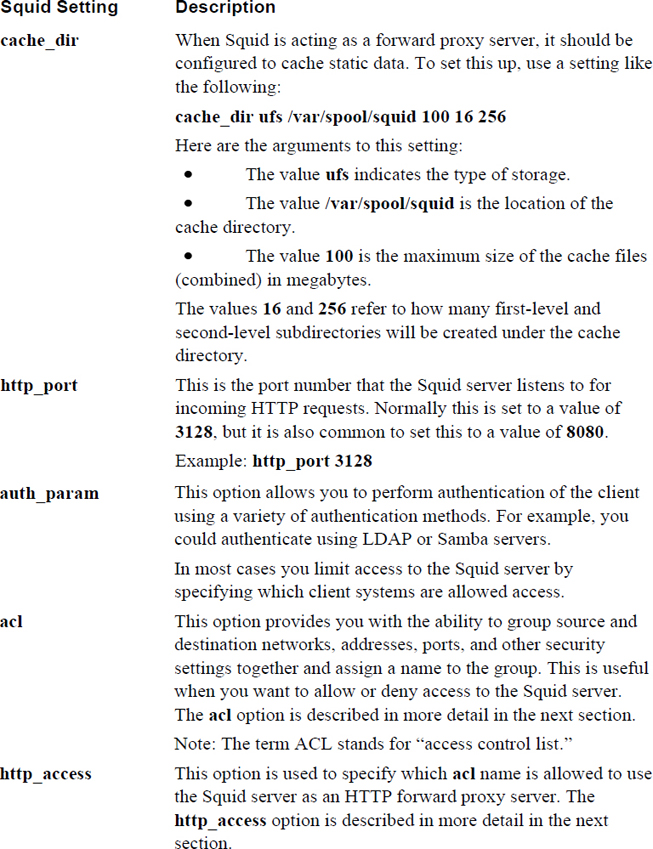

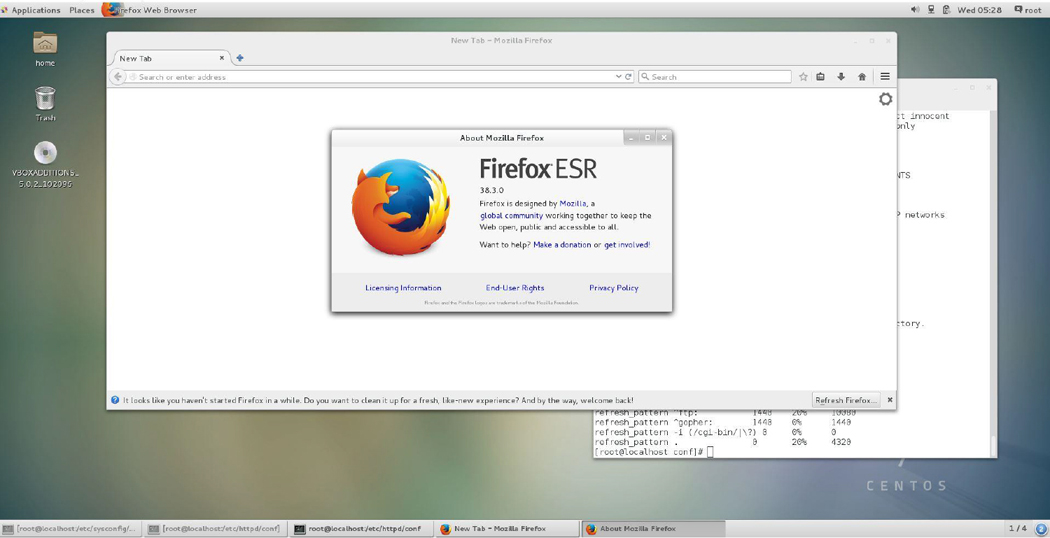

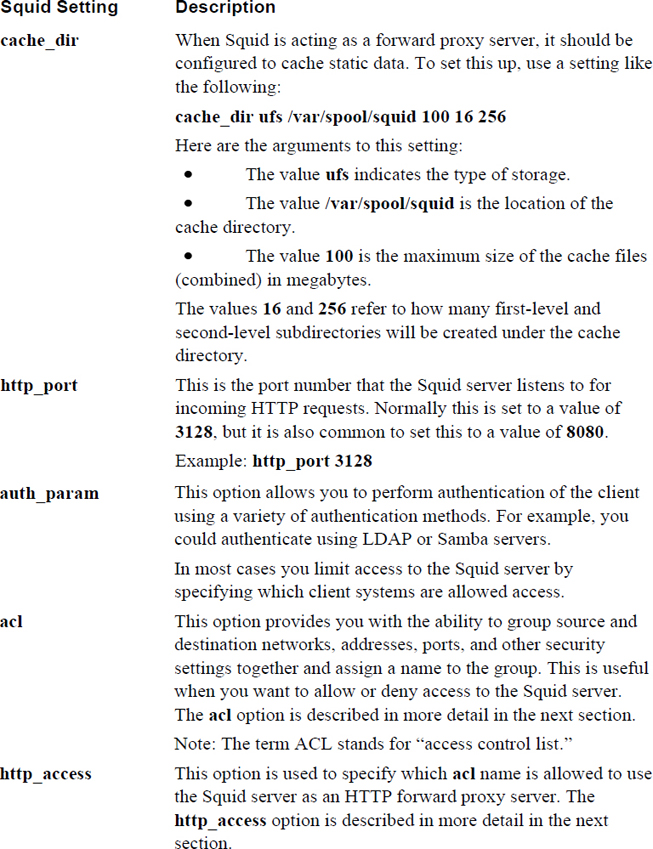

Chapter 21, “Network Service Configuration: Web Services,” covers the process of configuring several network-based tools, including the Apache Web Server and Squid.

Chapter 22, “Connecting to Remote Systems,” discusses how to connect to remote systems via the network.

Chapter 23, “Develop a Network Security Policy,” provides you with the means to create a security policy using the knowledge you acquire in Chapters 18–22.

Chapter 24, “Process Control,” covers how to start, view, and control processes (programs).

Chapter 25, “System Logging,” covers how to view system logs as well as how to configure the system to create custom log entries.

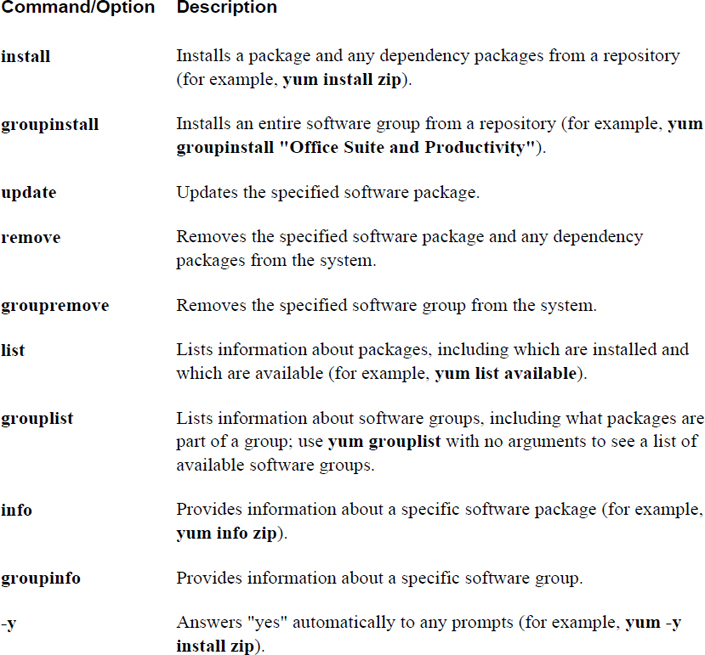

Chapter 26, “Red Hat–Based Software Management,” covers how to administer software on Red Hat–based systems such as Fedora and CentOS.

Chapter 27, “Debian-Based Software Management,” covers how to administer software on Debian-based systems, such as Ubuntu.

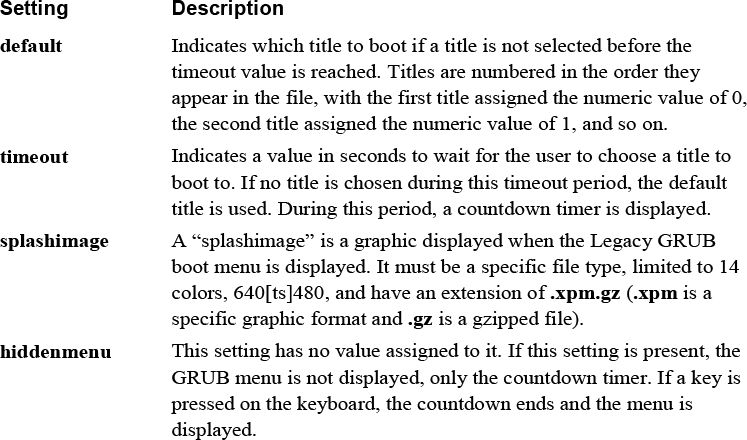

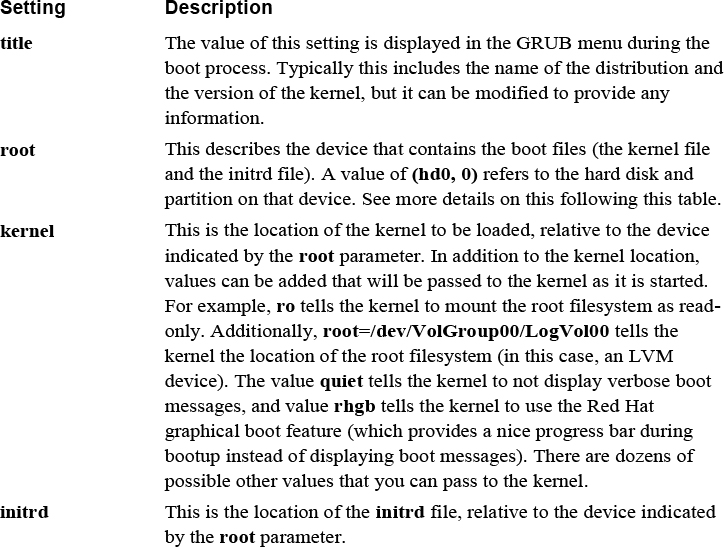

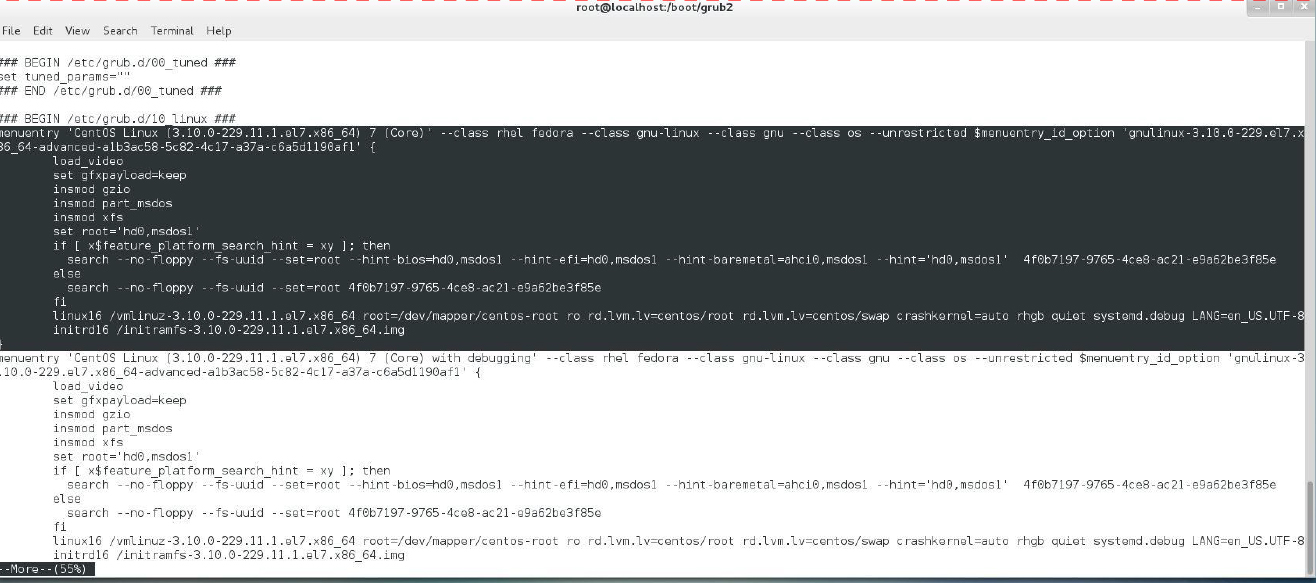

Chapter 28, “System Booting,” covers the process of configuring several network-based tools.

Chapter 29, “Develop a Software Management Security Policy,” provides you with the means to create a security policy using the knowledge you acquire in Chapters 26–28.

Chapter 30, “Footprinting,” covers the techniques that hackers use to discover information about systems. By learning about these techniques, you should be able to form a better security plan.

Chapter 31, “Firewalls,” explores how to configure software that protects your systems from network-based attacks.

Chapter 32, “Intrusion Detection,” provides you with an understanding of tools and techniques to determine if someone has successful compromised the security of your systems.

Chapter 33, “Additional Security Tasks,” covers a variety of additional Linux security features, including the fail2ban service, virtual private networks (VPNs), and file encryption.

Before you start learning about all the features and capabilities of Linux, it would help to get a firm understanding of what Linux is, including what the major components are of a Linux operating system. In this first chapter, you learn about some of the essential concepts of Linux. You discover what a distribution is and how to pick a distribution that best suits your needs. You are also introduced to the process of installing Linux, both on a bare-metal system and in a virtual environment.

After reading this chapter and completing the exercises, you will be able to do the following:

Describe is the various parts of Linux

Identify the major components that make up the Linux operating system

Describe different types of Linux distributions

Identify the steps for installing Linux

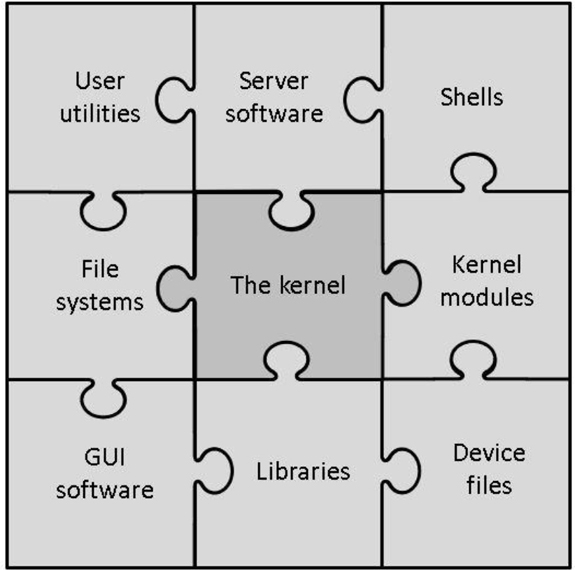

Linux is an operating system, much like Microsoft Windows. However, this is a very simplistic way of defining Linux. Technically, Linux is a software component called the kernel, and the kernel is the software that controls the operating system.

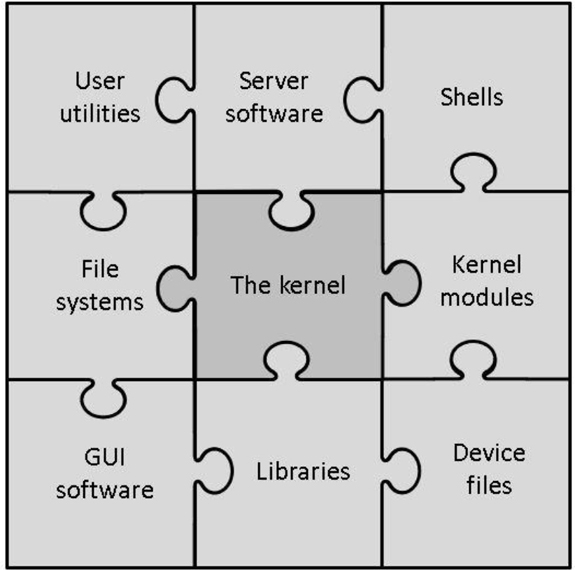

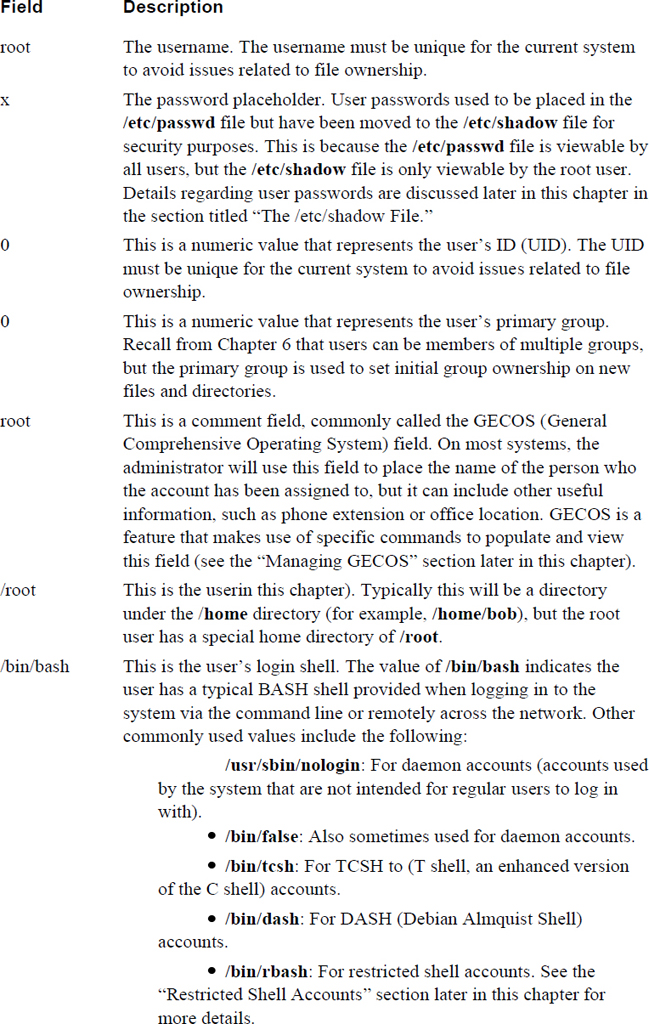

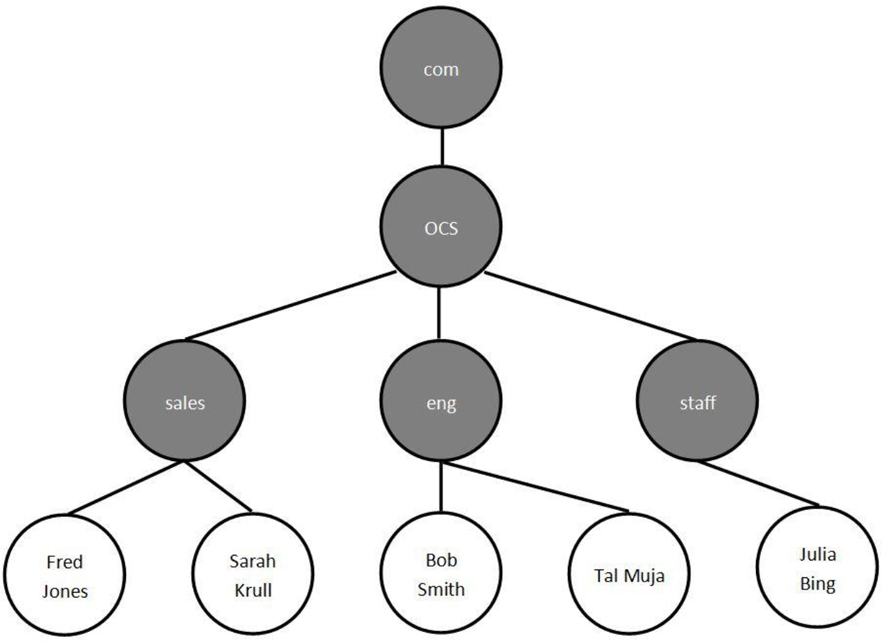

By itself, the kernel doesn’t provide enough functionality to provide a full operating system. In reality, many different components are brought together to define what IT professionals refer to as the Linux operating system, as shown in Figure 1-1.

Figure 1-1 The Components of the Linux Operating System

It is important to note that not all the components described in Figure 1-1 are always required for a Linux operating system. For example, there is no need for a graphical user interface (GUI). In fact, on Linux server systems, the GUI is rarely installed because it requires additional hard drive space, CPU cycles, and random access memory (RAM) usage. Also, it could pose a security risk.

Security Highlight

You may wonder how GUI software could pose a security risk. In fact, any software component poses a security risk because it is yet another part of the operating system that can be compromised. When you set up a Linux system, always make sure you only install the software required for that particular use case.

The pieces of the Linux operating system shown in Figure 1-1 are described in the following list:

• User utilities: Software that is used by users. Linux has literally thousands of programs that either run within a command line or GUI environment. Many of these utilities will be covered throughout this book.

• Server software: Software that is used by the operating system to provide some sort of feature or access, typically across a network. Common examples include a file-sharing server, a web server that provides access to a website, and a mail server.

• Shells: To interact with a Linux operating system via the command line, you need to run a shell program. Several different shells are available, as discussed later in this chapter.

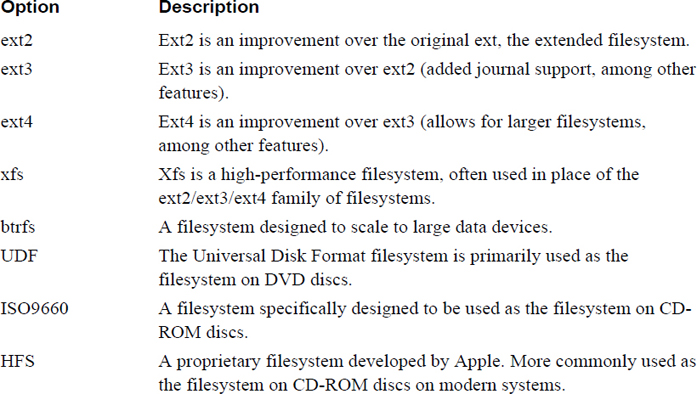

• File systems: As with an operating system, the files and directories (aka folders) are stored in a well-defined structure. This structure is called a file system. Several different file systems are available for Linux. Details on this topic are covered in Chapter 10, “Manage Local Storage: Essentials,” and Chapter 11, “Manage Local Storage: Advanced Features.”

• The kernel: The kernel is the component of Linux that controls the operating system. It is responsible for interacting with the system hardware as well as key functions of the operating system.

• Kernel modules: A kernel module is a program that provides more features to the kernel. You many hear that the Linux kernel is a modular kernel. As a modular kernel, the Linux kernel tends to be more extensible, secure, and less resource intensive (in other words, it’s lightweight).

• GUI software: Graphical user interface (GUI) software provides “window-based” access to the Linux operating system. As with command-line shells, you have a lot of options when it comes to picking a GUI for a Linux operating system. GUI software is covered in more detail later in this chapter.

• Libraries: This is a collection of software used by other programs to perform specific tasks. Although libraries are an important component of the Linux operating system, they won’t be a major focus of this book.

• Device files: On a Linux system, everything can be referred to as a file, including hardware devices. A device file is a file that is used by the system to interact with a device, such as a hard drive, keyboard, or network card.

The various bits of software that make up the Linux operating system are very flexible. Additionally, most of the software is licensed as “open source,” which means the cost to use this software is often nothing. This combination of features (flexible and open source) has given rise to a large number of Linux distributions.

A Linux distribution (also called a distro) is a specific implementation of a Linux operating system. Each distro will share many common features with other distros, such as the core kernel, user utilities, and other components. Where distros most often differ is their overall goal or purpose. For example, the following list describes several common distribution types:

• Commercial: A distro that is designed to be used in a business setting. Often these distros will be bundled together with a support contract. So, although the operating system itself may be free, the support contract will add a yearly fee. Commercial releases normally have a slower release cycle (3–5 years), resulting in a more stable and secure platform. Typical examples of commercial distros include Red Hat Enterprise Linux and SUSE.

• Home or amateur: These distros are focused on providing a Linux operating system to individuals who want a choice that isn’t either macOS or Microsoft Windows. Typically there is only community support for these distros, with very rapid release cycles (3–6 months), so all of the latest features are quickly available. Typical examples of amateur distros include Fedora, Linux Mint, and Ubuntu (although Ubuntu also has a release that is designed for commercial users).

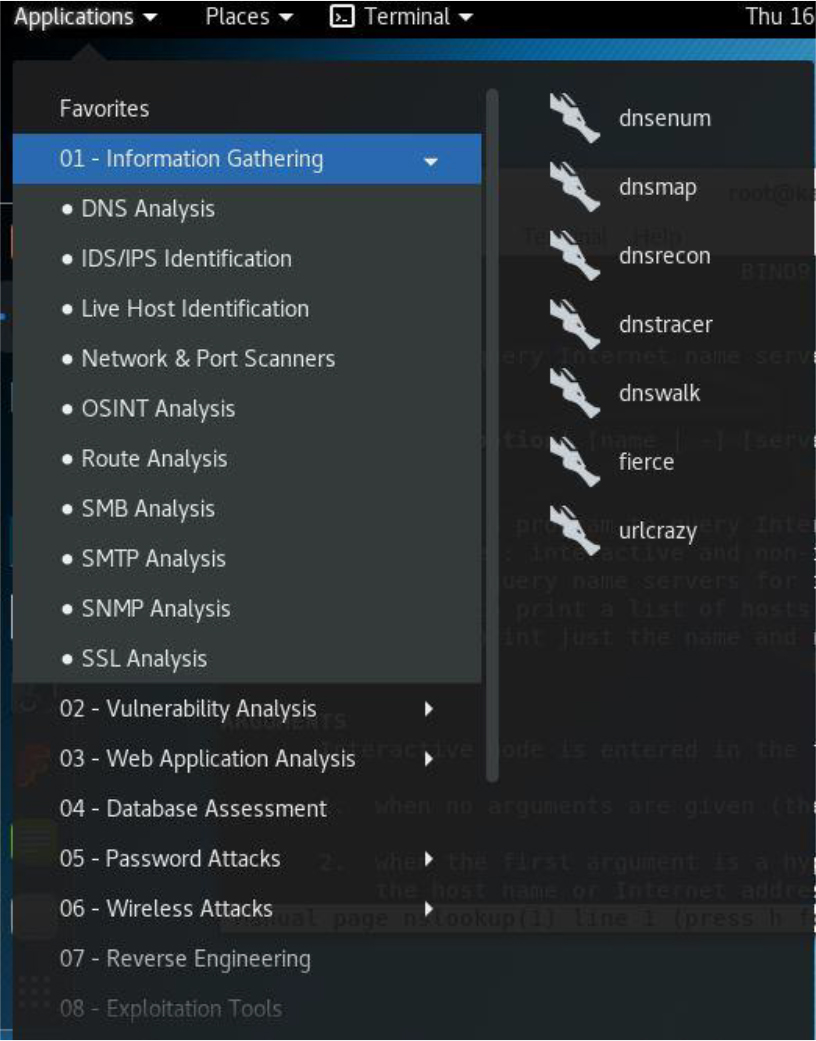

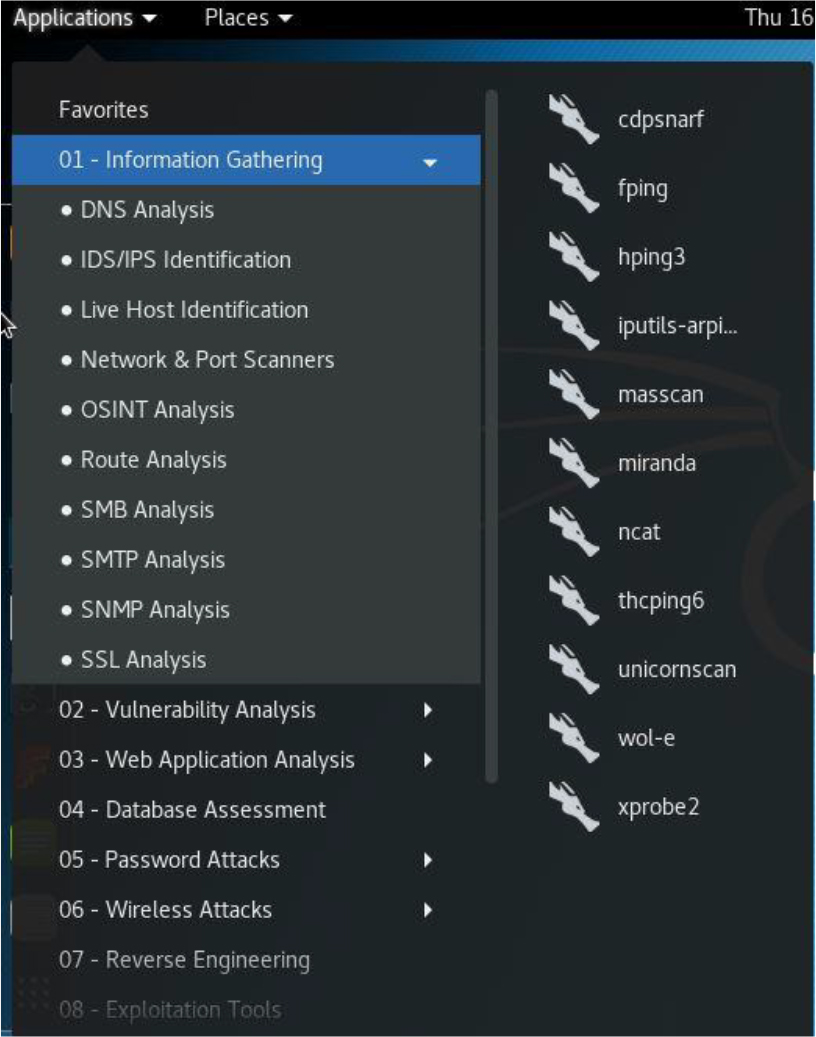

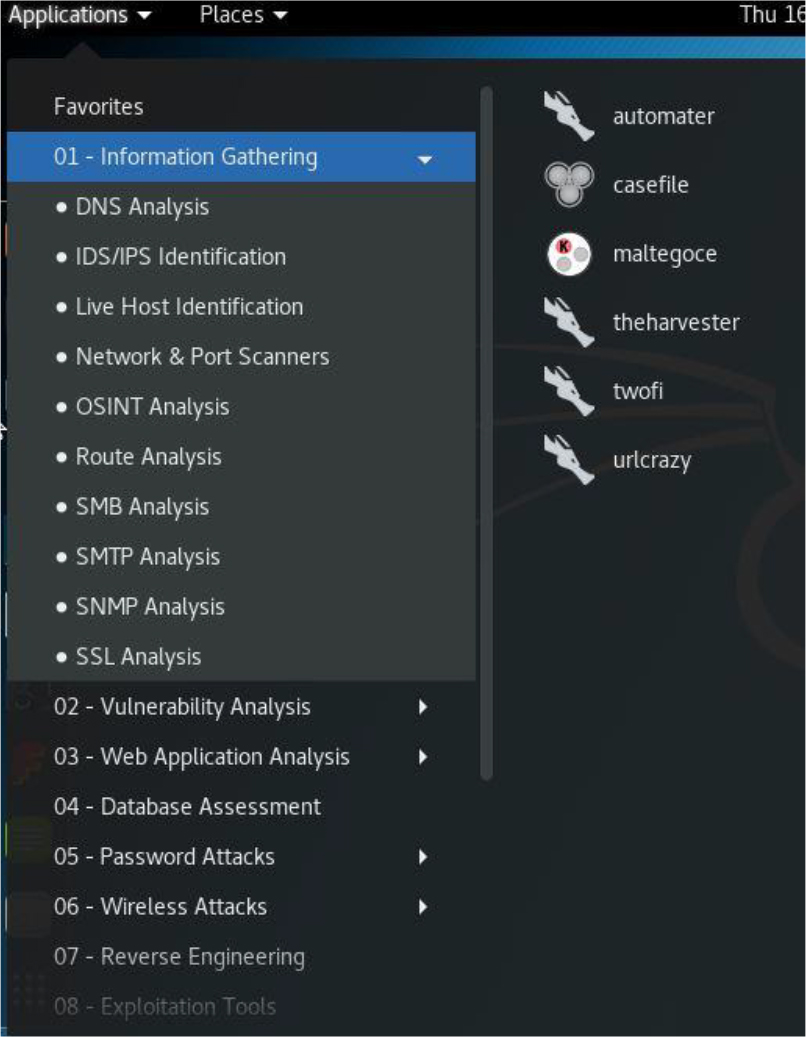

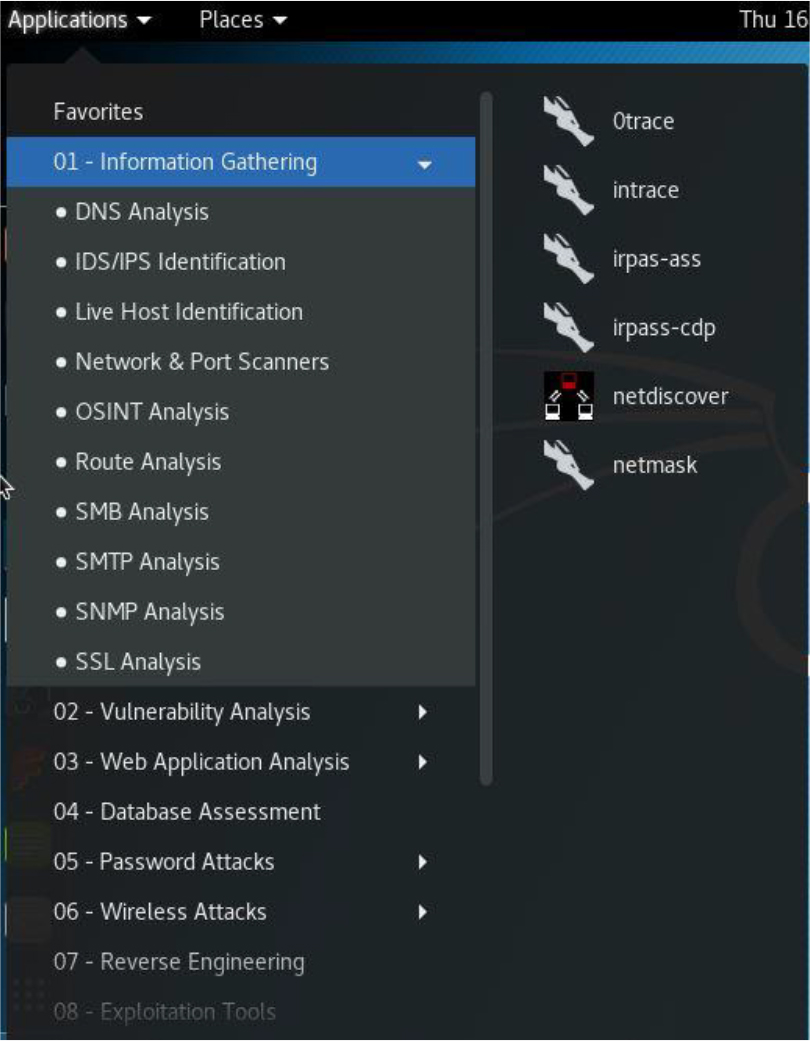

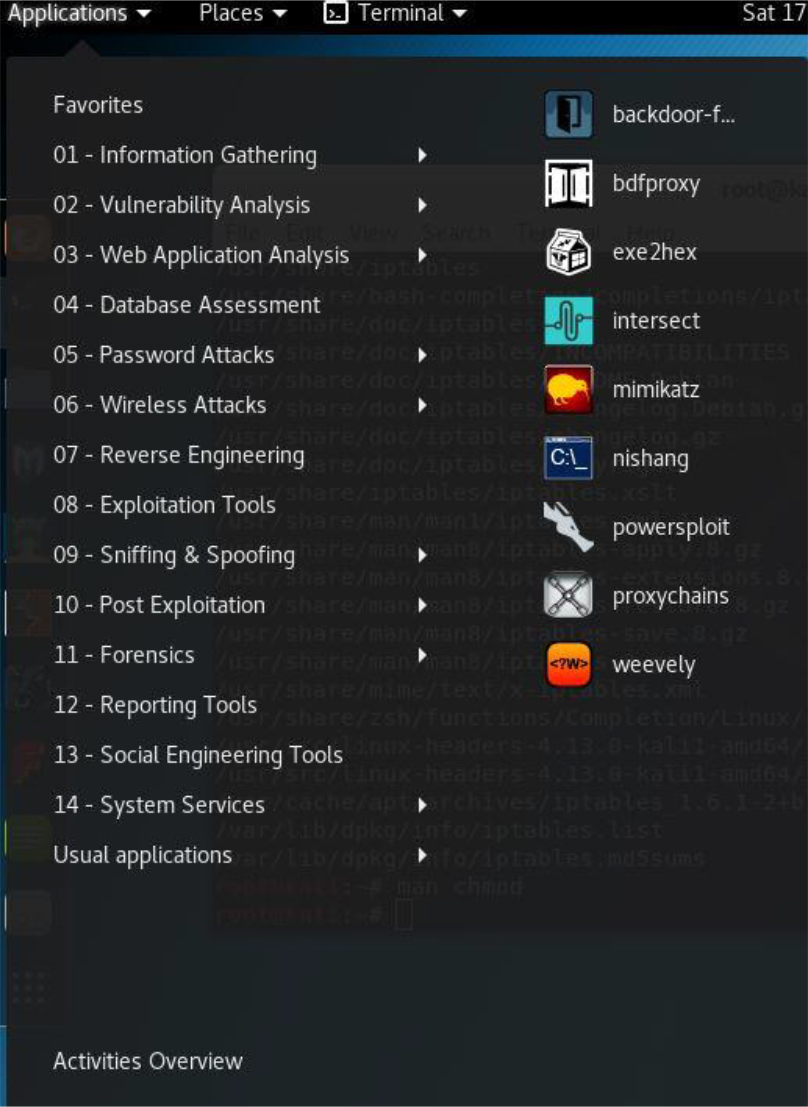

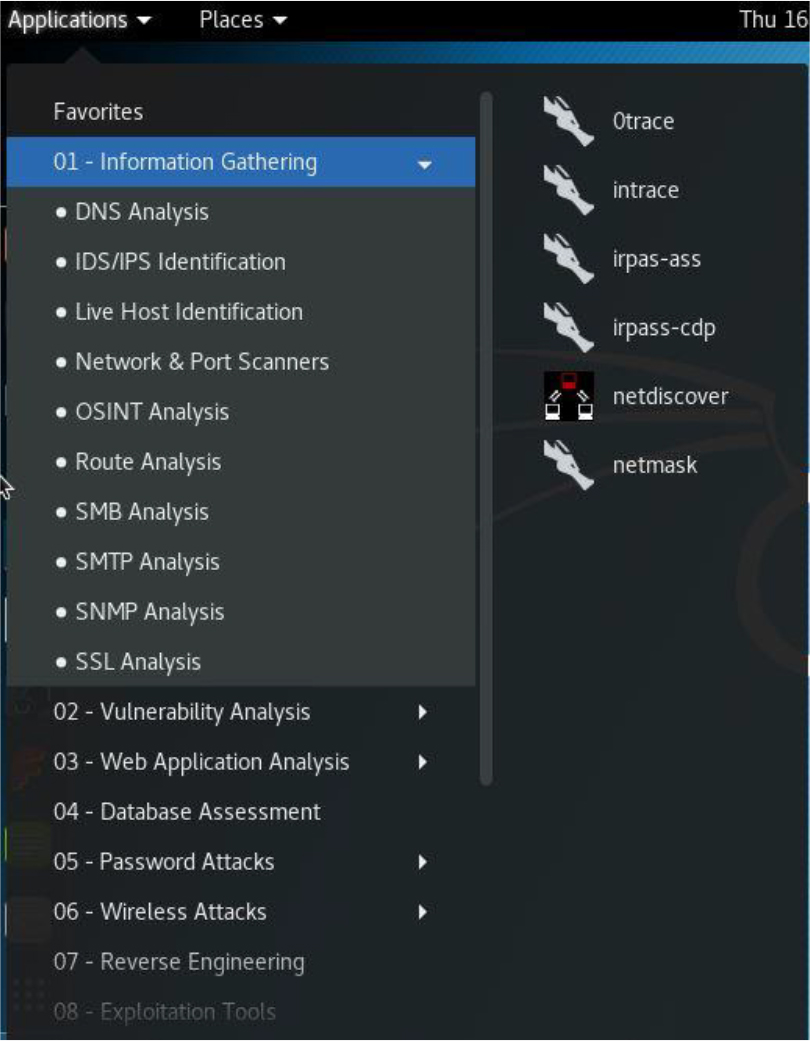

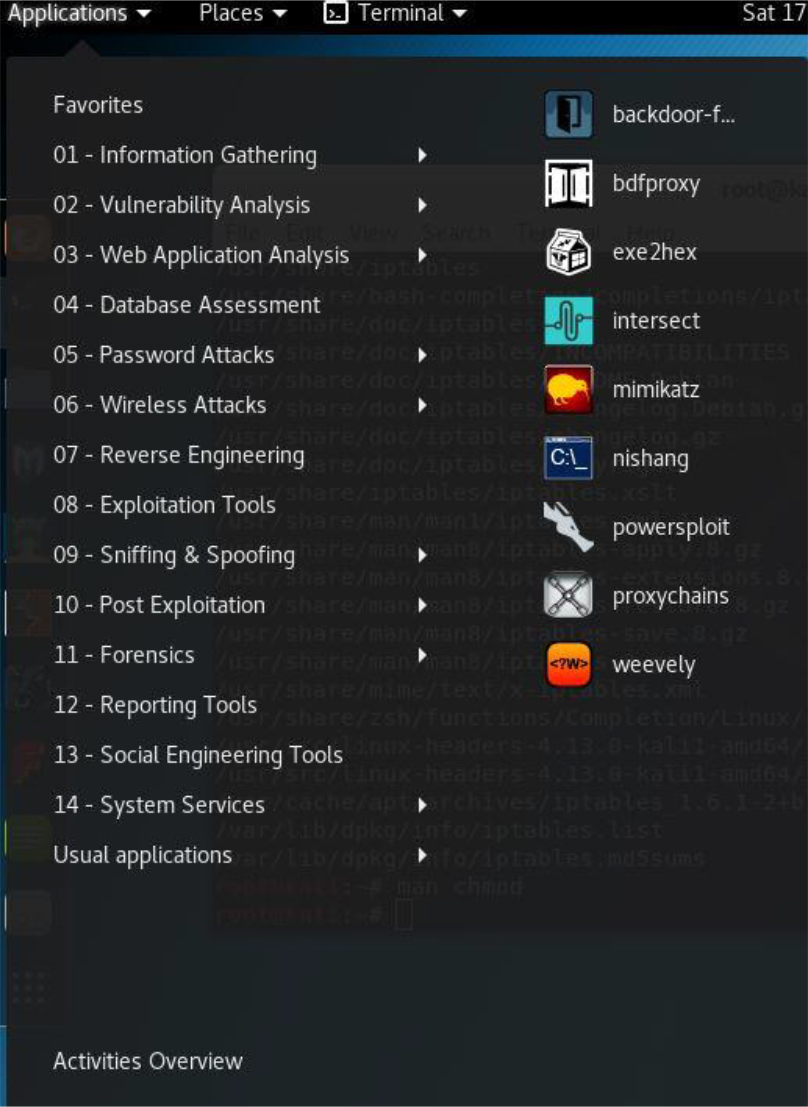

• Security enhanced: Some distributions are designed around security. Either the distro itself has extra security features or it provides tools to enhance the security on other systems. Typical examples include Kali Linux and Alpine Linux.

• Live distros: Normally to use an operating system, you would first need to install it on a system. With a Live distribution, the system can boot directly from removable media, such as a CD-ROM, DVD, or USB disk. The advantage of Live distros is the ability to test out a distribution without having to make any changes to the contents of the system’s hard drive. Additionally, some Live distros come with tools to fix issues with the installed operating system (including Microsoft Windows issues). Typical examples of Live distros include Manjaro Linux and Antegros. Most modern amateur distros, such as Fedora and Linux Mint, also have a Live version.

Security Highlight

Commercial distributions tend to be more secure than distributions designed for home use. This is because commercial distributions are often used for system-critical tasks in corporations or the government, so the organizations that support these distributions often make security a key component of the operating system.

It is important to realize that these are only a few of the types of Linux distributions. There are also distros designed for educational purposes, young learners, beginners, gaming, older computers, and many others. An excellent source to learn more about available distributions is https://distrowatch.com. This site provides the ability to search for and download the software required to install many different distributions.

A shell is a software program that allows a user to issue commands to the system. If you have worked in Microsoft Windows, you may have used the shell environment provided for that operating system: DOS. Like DOS, the shells in Linux provide a command-line interface (CLI) to the user.

CLI commands provide some advantages. They tend to be more powerful and have more functions than commands in GUI applications. This is partly because creating CLI programs is easier than creating GUI programs, but also because some of the CLI programs were created even before GUI programs existed.

Linux has several different shells available. Which shells you have on your system will depend on what software has been installed. Each shell has specific features, functions, and syntax that differentiate it from other shells, but they all essentially perform the same functionality.

Although multiple different shells are available for Linux, by far the most popular shell is the BASH shell. The BASH shell was developed from an older shell named the Bourne Shell (BASH stands for Bourne Again SHell). Because it is so widely popular, it will be the primary focus of the discussions in this book.

When you install a Linux operating system, you can decide if you only want to log in and interact with the system via the CLI or if you want to install a GUI. GUI software allows you to use a mouse and keyboard to interact with the system, much like you may be used to within Microsoft Windows.

For personal use, on laptop and desktop systems, having a GUI is normally a good choice. The ease of using a GUI environment often outweighs the disadvantages that this software creates. In general, GUI software tends to be a big hog of system resources, taking up a higher percentage of CPU cycles and RAM. As a result, it is often not installed on servers, where these resources should be reserved for critical server functions.

Security Highlight

Consider that every time you add more software to the system, you add a potential security risk. Each software component must be properly secured, and this is especially important for any software that provides the means for a user to access a system.

GUI-based software is a good example of an additional potential security risk. Users can log in via a GUI login screen, presenting yet another means for a hacker to exploit the system. For this reason, system administrators tend to not install GUI software on critical servers.

As with shells, a lot of options are available for GUI software. Many distributions have a “default” GUI, but you can always choose to install a different one. A brief list of GUI software includes GNOME, KDE, XFCE, LXDE, Unity, MATE, and Cinnamon.

GUIs will not be a major component of this book. Therefore, we the authors suggest you try different GUIs and pick one that best meets your needs.

Before installing Linux, you should answer the following questions:

• Which distribution will you choose? As previously mentioned, you have a large number of choices.

• What sort of installation should be performed? You have a couple of choices here because you can install Linux natively on a system or install the distro as a virtual machine (VM).

• If Linux is installed natively, is the hardware supported? In this case, you may want to shy away from newer hardware, particularly on newer laptops, as they may have components that are not yet supported by Linux.

• If Linux is installed as a VM, does the system have enough resources to support both a host OS and a virtual machine OS? Typically this comes does to a question of how much RAM the system has. In most cases, a system with at least 8GB of RAM should be able to support at least one VM.

You might be asking yourself, “How hard can it be to pick a distribution? How many distros can there be?” The simple answer to the second question is “a lot.” At any given time, there are about 250 active Linux distributions. However, don’t let that number scare you off!

Although there are many distros, a large majority of them are quite esoteric, catering to very specific situations. While you are learning Linux, you shouldn’t concern yourself with these sorts of distributions.

Conversational Learning™ — Choosing a Linux Distribution

Gary: Hey, Julia.

Julia: You seem glum. What’s wrong, Gary?

Gary: I am trying to decided which Linux distro to install for our new server and I’m feeling very much overwhelmed.

Julia: Ah, I know the feeling, having been there many times before. OK, so let’s see if we can narrow it down. Do you feel you might need professional support for this system?

Gary: Probably not… well, not besides the help I get from you!

Julia: I sense more emails in my inbox soon. OK, that doesn’t narrow it down too much. If you had said “yes,” I would have suggested one of the commercial distros, like Red Hat Enterprise Linux or SUSE.

Gary: I’d like to pick one of the more popular distros because I feel they would have more community support.

Julia: That’s a good thought. According to distrowatch.com, there are several community-supported distros that have a lot of recent downloads, including Mint, Debian, Ubuntu, and Fedora.

Gary: I’ve heard of those, but there are others listed on distrowatch.com that I’ve never heard of before.

Julia: Sometimes those other distros may have some features that you might find useful. How soon do you need to install the new server?

Gary: Deadline is in two weeks.

Julia: OK, I recommend doing some more research on distrowatch.com, pick three to four candidates and install them on a virtual machine. Spend some time testing them out, including using the software that you will place on the server. Also spend some time looking at the community support pages and ask yourself if you feel they will be useful.

Gary: That sounds like a good place to start.

Julia: One more thing: consider that there isn’t just one possible solution. Several distros will likely fit your needs. Your goal is to eliminate the ones that won’t fit your needs first and then try to determine the best of the rest. Good luck!

A handful of distributions are very popular and make up the bulk of the Linux installations in the world. However, a complete discussion of the pros and cons of each of these popular distros is beyond the scope of this book. For the purpose of learning Linux, we the authors recommend you install one or more of the following distros:

• Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL), Fedora, or CentOS: These distributions are called Red Hat–based distros because they all share a common set of base code from Red Hat’s release of Linux. There are many others that share this code, but these are generally the most popular. Note that both Fedora and CentOS are completely free, while RHEL is a subscription-based distro. For Red Hat–based examples in this book, we will use Fedora.

• Linux Mint, Ubuntu, or Debian: These distributions are called Debian-based distros because they all share a common set of base code from Debian’s release of Linux. There are many others that share this code, but these are generally the most popular. For Debian-based examples in this book, we will use Ubuntu.

• Kali: This is a security-based distribution that will be used in several chapters of this book. Consider this distribution to be a tool that enables you to determine what security holes are present in your environment.

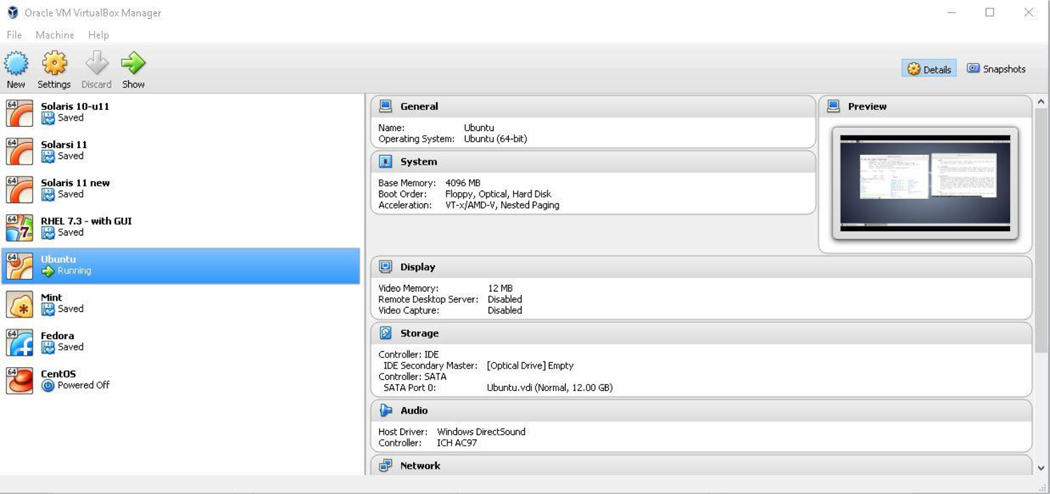

If you have an old computer available, you can certainly use it to install Linux natively (this is called a bare-metal or native installation). However, given the fact that you probably want to test several distributions, virtual machine (VM) installs are likely a better choice.

A VM is an operating system that thinks it is installed natively, but it is actually sharing a system with a host operating system. (There is actually a form of virtualization in which the VM is aware it is virtualized, but that is beyond the scope of this book and not necessary for learning Linux.) The host operating system can be Linux, but it could also be macOS or Microsoft Windows.

In order to create VMs, you need a product that provides a hypervisor. A hypervisor is software that presents “virtual hardware” to a VM. This includes a virtual hard drive, a virtual network interface, a virtual CPU, and other components typically found on a physical system. There are many different hypervisor software programs, including VMware, Microsoft Hyper-V, Citrix XenServer, and Oracle VirtualBox. You could also make use of hosted hypervisors, which are cloud-based applications. With these solutions, you don’t even have to install anything on your local system. Amazon Web Services is a good example of a cloud-based service that allows for hosted hypervisors.

Security Highlight

Much debate in the security industry revolves around whether virtual machines are more secure than bare-metal installations. There is no simple answer to this question because many aspects need to be considered. For example, although virtual machines may provide a level of abstraction, making it harder for a hacker to be aware of their existence, they also result in another software component that needs to be properly secured.

Typically, security isn’t the primary reason why an organization uses virtual machines (better hardware utilization is usually the main reason). However, if you choose to use virtual machines in your environment, the security impact should be carefully considered and included in your security policies.

For the purposes of learning Linux, we will use Oracle VirtualBox. It is freely available and works well on multiple platforms, including Microsoft Windows (which is most likely the operating system you already have installed on your own system). Oracle VirtualBox can be downloaded from https://www.virtualbox.org. The installation is fairly straightforward: just accept the default values or read the installation documentation (https://www.virtualbox.org/wiki/Downloads#manual).

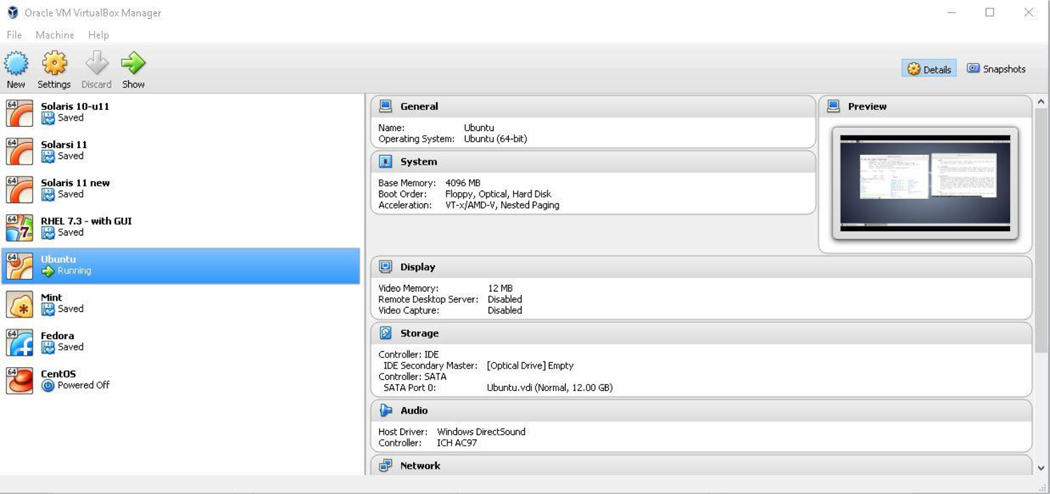

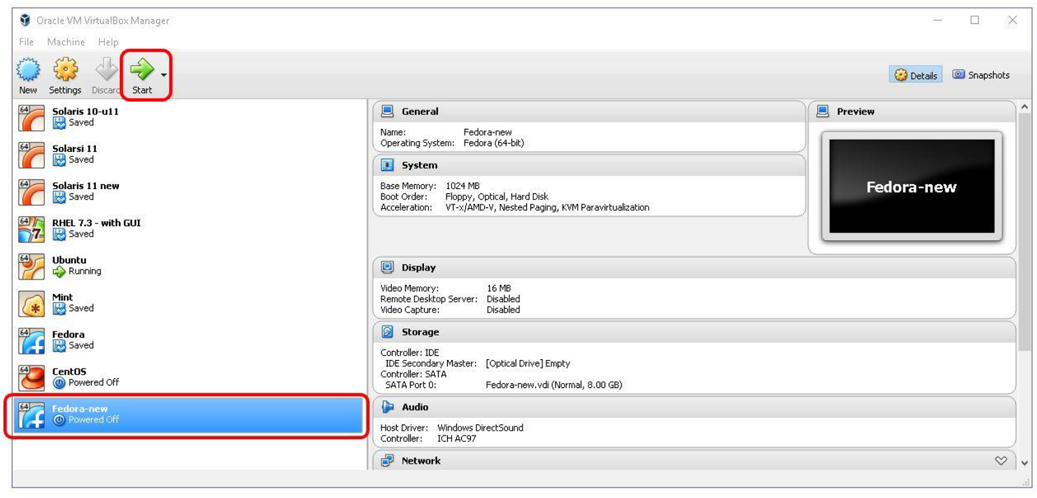

After you have installed Oracle VirtualBox and have installed some virtual machines, the Oracle VM VirtualBox Manager will look similar to Figure 1-2.

Figure 1-2 The Oracle VirtualBox VM Manager

If you are using Oracle VirtualBox, the first step to installing a distro is to add a new “machine.” This is accomplished by taking the following steps in the Oracle VM VirtualBox Manager:

1. Click Machine and then New.

2. Provide a name for the VM; for example, enter Fedora in the Name: box. Note that the Type and Version boxes will likely change automatically. Type should be Linux. Check the install media you downloaded to see if it is a 32-bit or 64-bit operating system (typically this info will be included in the filename). Most modern version are 64 bit.

3. Set the Memory Size value by using the sliding bar or typing the value in the MB box. Typically a value of 4196MB (about 4GB) of memory is needed for a full Linux installation to run smoothly.

Leave the option “Create a virtual hard disk now” marked.

4. Click the Create button.

5. On the next dialog box, you will choose the size of the virtual hard disk. The default value will likely be 8.00GB, which is a bit small for a full installation. A recommend minimum value is 12GB.

6. Leave the “Hard disk file type” set to VDI (Virtual Hard Disk). Change “Storage on physical hard disk” to Fixed Size.

7. Click the Create button.

After a short period of time (a few minutes), you should see your new machine in the list on the left side of the Oracle VM VirtualBox Manager. Before continuing to the next step, make sure you know the location of your installation media (the *.iso file of the Linux distro you downloaded).

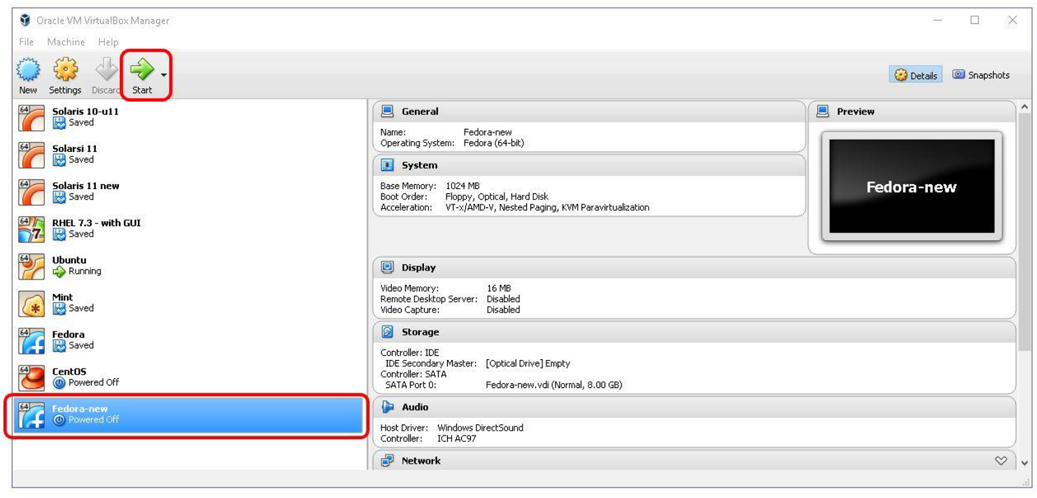

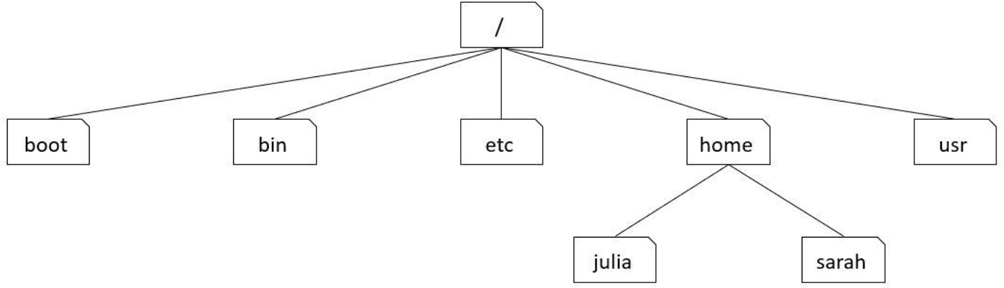

To start the installation process, click the new machine and then click the Start button. See Figure 1-3 for an example.

Figure 1-3 Start the Installation Process

In the next window that appears, you need to select the installation media. In the Select Start-up Disk dialog box, click the small icon that looks like a folder with a green “up arrow.” Then navigate to the folder that contains the installation media, select it, and click the Open button. When you return to the dialog box, click the Start button.

Once the installation starts, the options and prompts really depend on which distribution you are installing. These can also change as newer versions of the distributions are released. As a result of how flexible these installation processes can be, we recommend you follow the installation guides provided by the organization that released the distribution.

Instead of providing specific instructions, we offer the following recommendations:

• Accept the defaults. Typically the default options work well for your initial installations. Keep in mind that you can always reinstall the operating system later.

• Don’t worry about specific software. One option may require that you select which software to install. Again, select the default provided. You can always add more software later, and you will learn how to do this in Chapter 25, “System Logging,” and Chapter 26, “Red Hat-Based Software Management.”

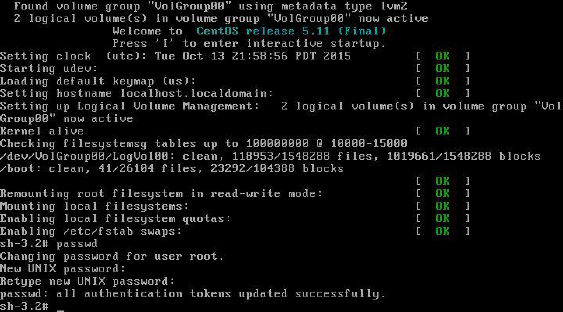

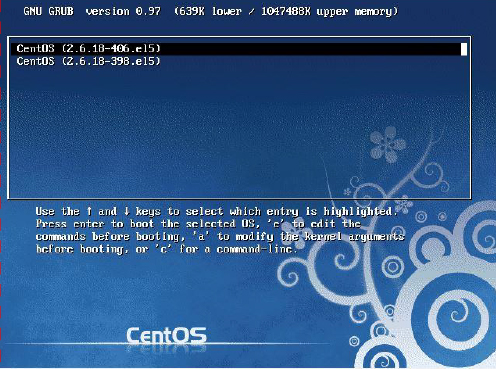

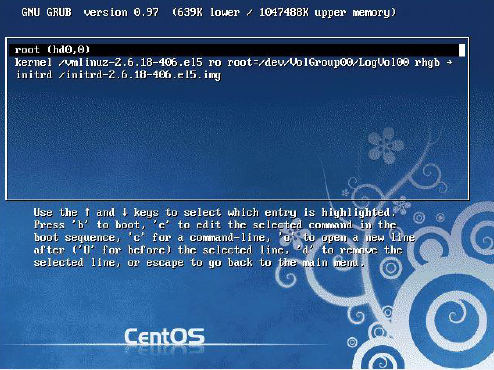

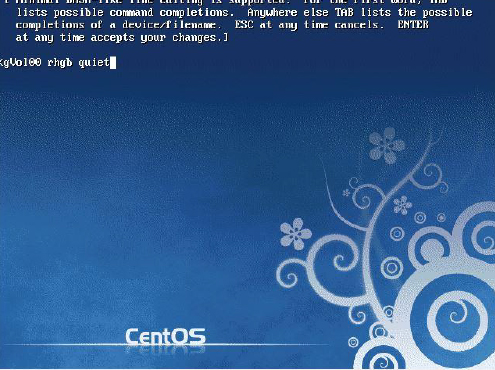

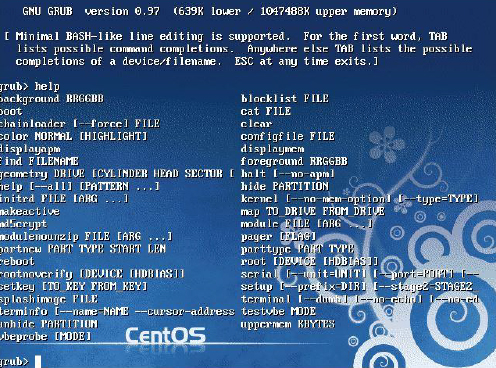

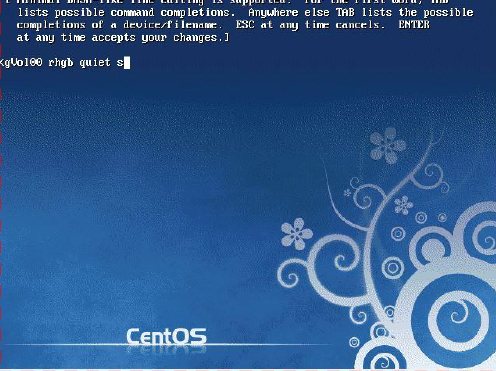

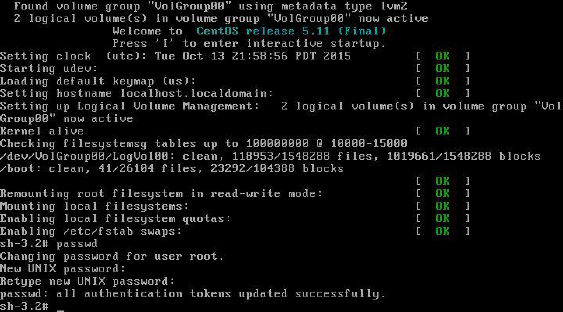

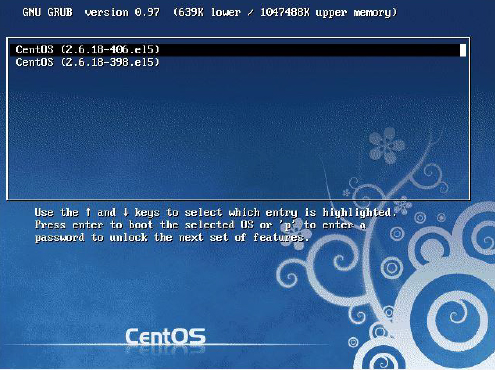

• Don’t forget that password. You will be asked to set a password for either the root account or a regular user account. On a production system, you should make sure you set a password that isn’t easy to compromise. However, on these test systems, pick a password that is easy to remember, as password security isn’t as big of a concern in this particular case. If you do forget your password, recovering passwords is covered in Chapter 28, “System booting,” (or you can reinstall the Linux OS).

After reading this chapter, you should have a better understanding of the major components of the Linux operating system. You should also know what a Linux distribution is and have an idea of the questions you should answer prior to installing Linux.

1. A _____ is a structure that is used to organize files and directories in an operating system.

2. Which of the following is not a common component of a Linux operating system?

a. kernel

b. libraries

c. disk drive

d. shells

3. Which of the following is a security-based Linux distribution?

a. Fedora

b. CentOS

c. Debian

d. Kali

4. A _____ program provides a command-line interface to the Linux operating system.

5. A _____ is an operating system that thinks it is installed natively, but it is actually sharing a system with a host operating system.

One of the more amazing features of Linux is the vast number of command-line utilities. There are literally thousands of commands, each of which is designed to perform a specific task. Having so many commands provides a great deal of flexibility, but it also makes the process of learning Linux a bit more daunting.

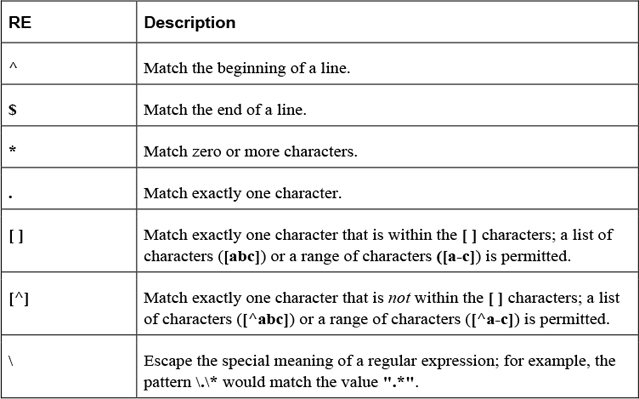

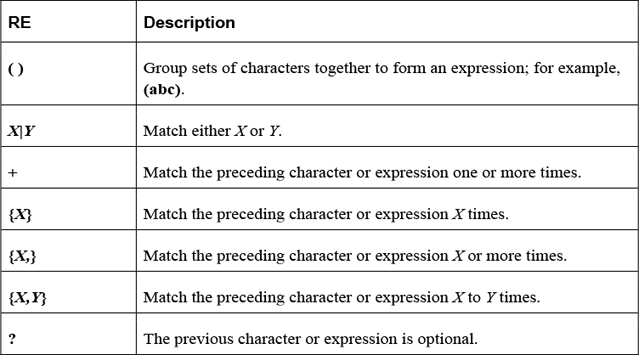

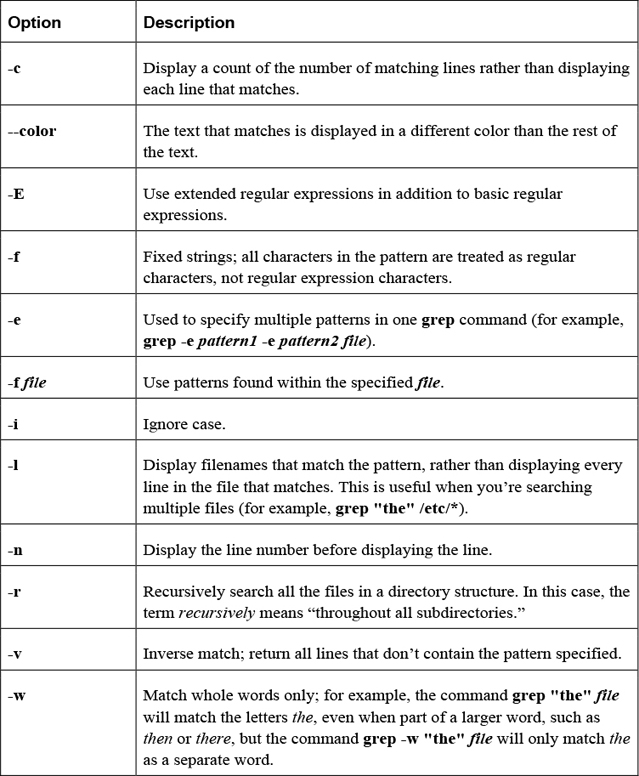

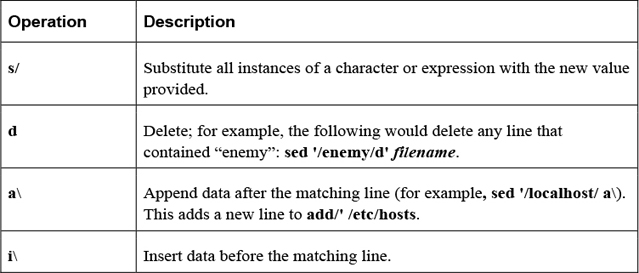

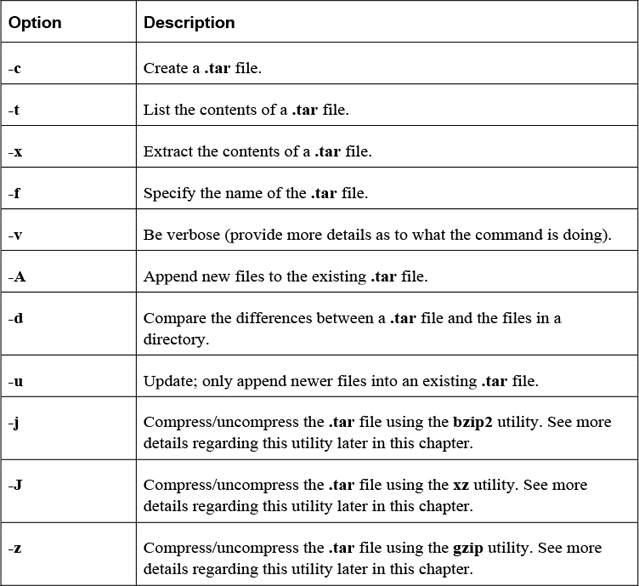

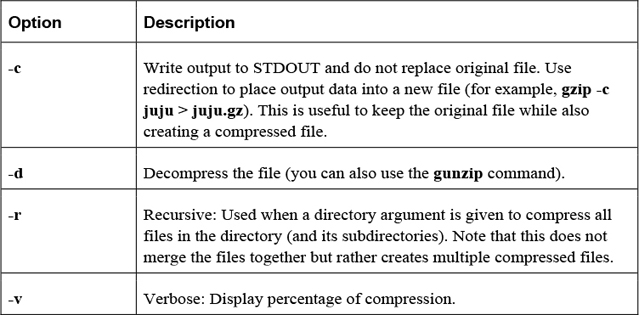

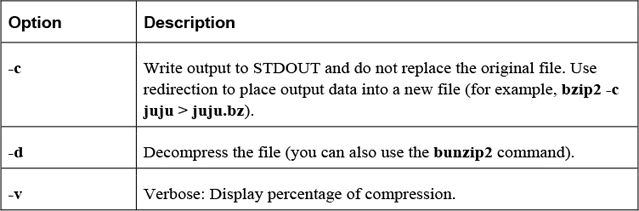

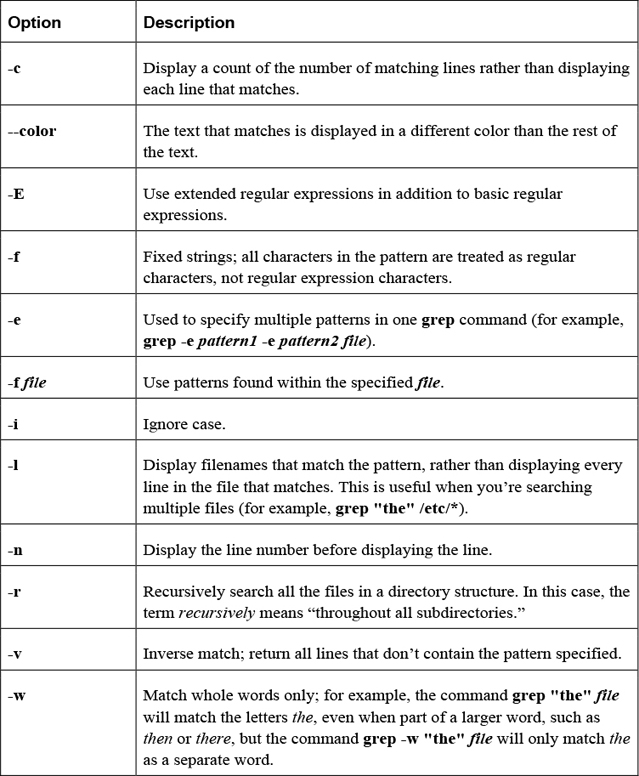

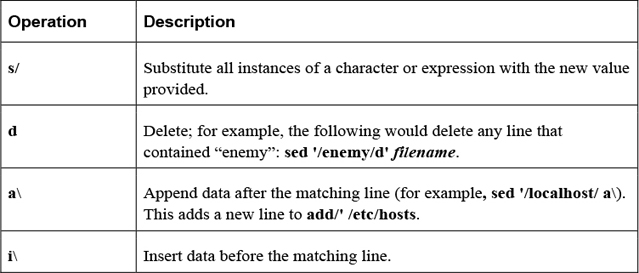

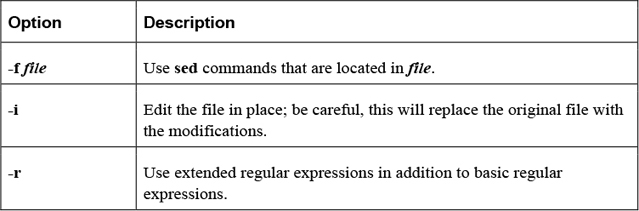

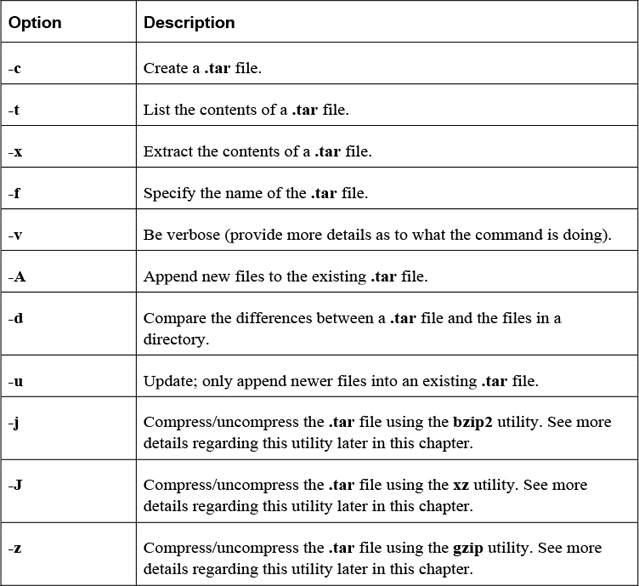

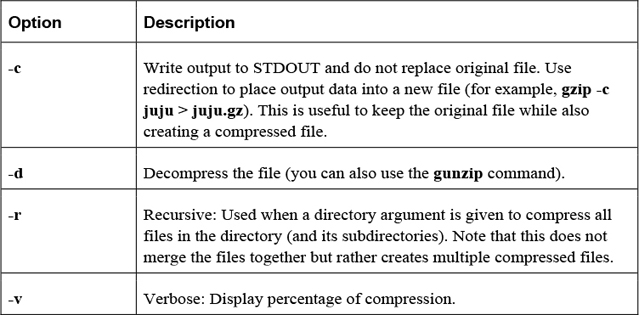

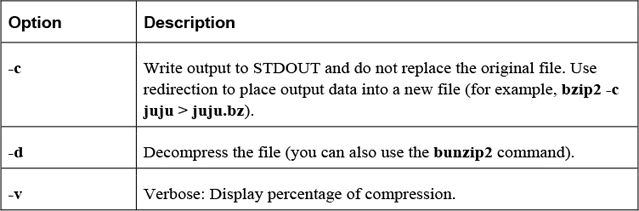

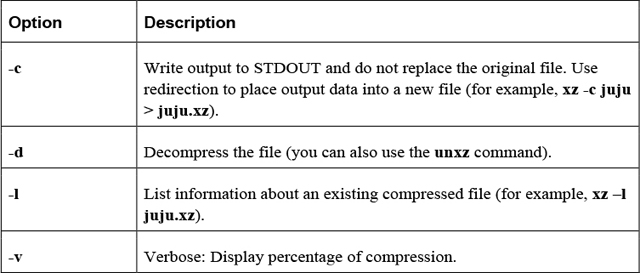

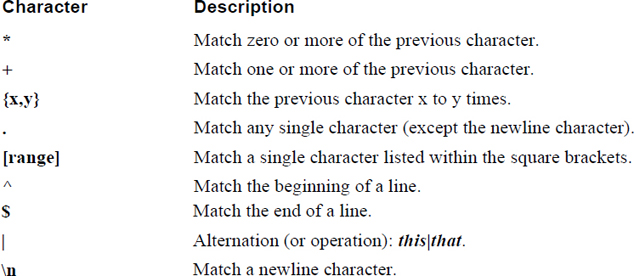

The goal of this chapter is to introduce you to some of the more essential command-line utilities. You learn commands used to manage files and directories, including how to view, copy, and delete files. You also learn the basics of a powerful feature called regular expressions, which allows you to view and modify files using patterns. This chapter introduces some of the more commonly used file-compression utilities, such as the tar and gzip utilities.

After reading this chapter and completing the exercises, you will be able to do the following:

Manage files and directories.

Use shell features such as shell variables.

Be able to re-execute previous commands using the shell feature called history.

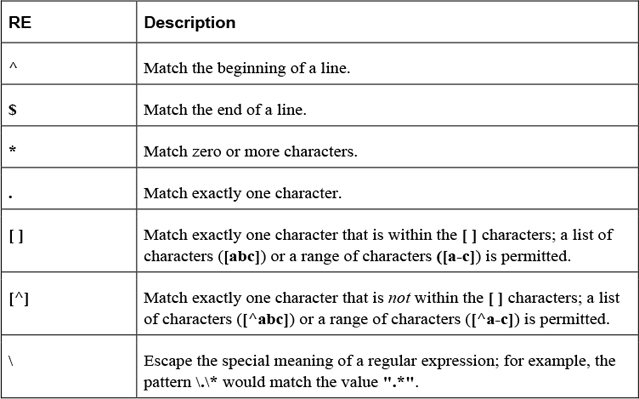

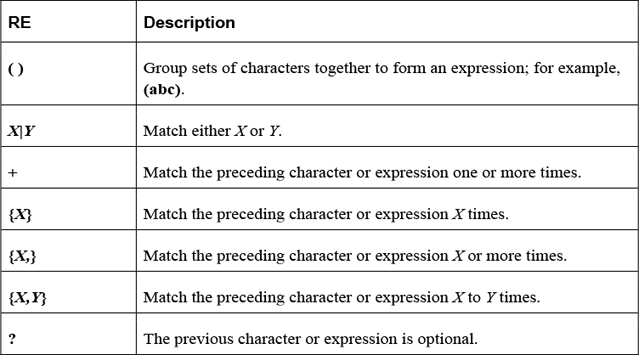

Identify regular expressions and know how to use them with commands like find, grep, and sed.

Manage file-compression utilities.

The Linux operating system includes a large number of files and directories. As a result, a major component of working on a Linux system is knowing how to manage files. In this section, you learn some of the essential command-line tools for file management.

Most likely you are already familiar with Microsoft Windows. That operating system makes use of drives to organize the different storage devices. For example, the primary hard drive is typically designated the C: drive. Additional drives, such as CD-ROM drives, DVD drives, additional hard drives, and removable storage devices (USB drives) are assigned D:, E:, and so on. Even network drives are often assigned a “drive letter” in Microsoft Windows.

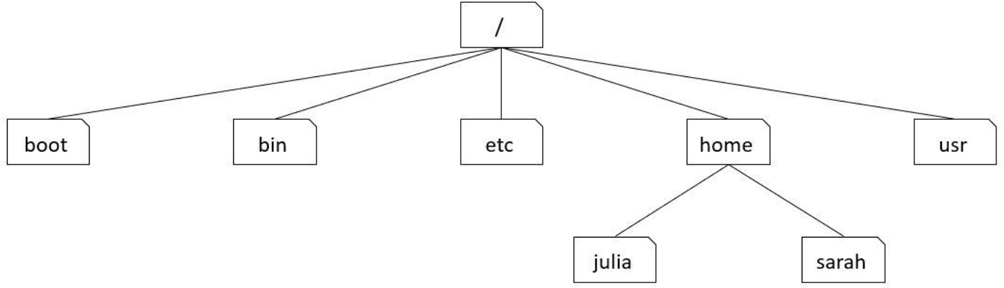

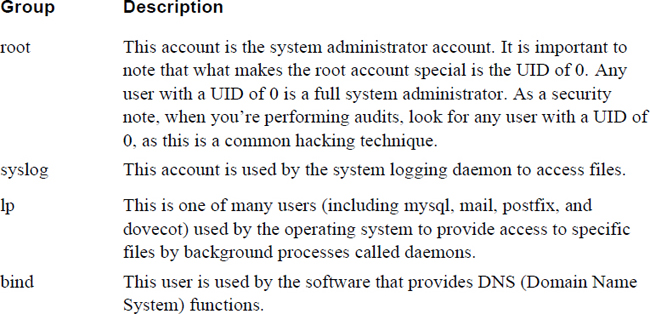

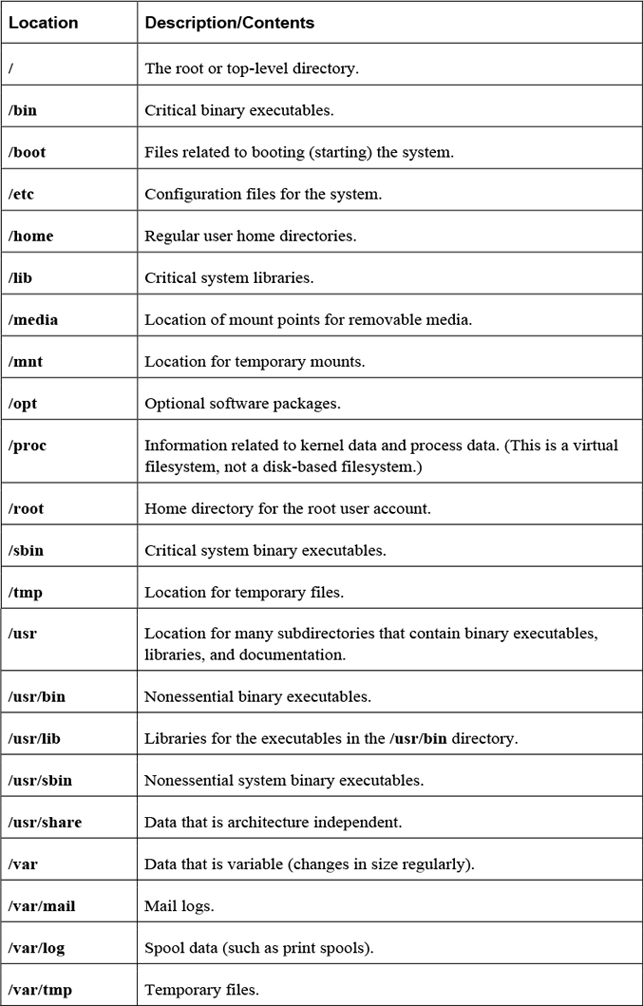

In Linux, a different method is used. Every storage location, including remote drives and removable media, is accessible under the top-level directory, named root. The root directory is symbolized by a single slash (/) character. See Figure 2-1 for a demonstration of a small portion of a Linux filesystem (a full Linux filesystem would contain hundreds, if not thousands, of directories).

Figure 2-1 Visual Example of a Small Portion of a Linux Filesystem

Using the example in Figure 2-1, the boot, bin, etc, home, and usr directories are considered to be “under” the / directory. The julia and sarah directories are considered to be “under” the home directory. Often the term subdirectory or child directory is used to describe a directory that is under another directory. The term parent directory is used to describe a directory that contains subdirectories. Hence, the home directory is the parent directory of the julia subdirectory.

To describe the location of a directory, a full path is often used that includes all the directories up to the root directory. For example, the julia directory can be described by the /home/julia path. In this path, the first / represents the root directory and all further / characters are used to separate additional directories in the path.

You may be wondering what is stored in these different directories. That is a good question, but also a difficult one to answer at this point given that you are just starting to learn about the Linux operating system. So although the answer will be provided here, realize this isn’t something you should worry about too much right now—these locations will make more sense as you explore Linux further.

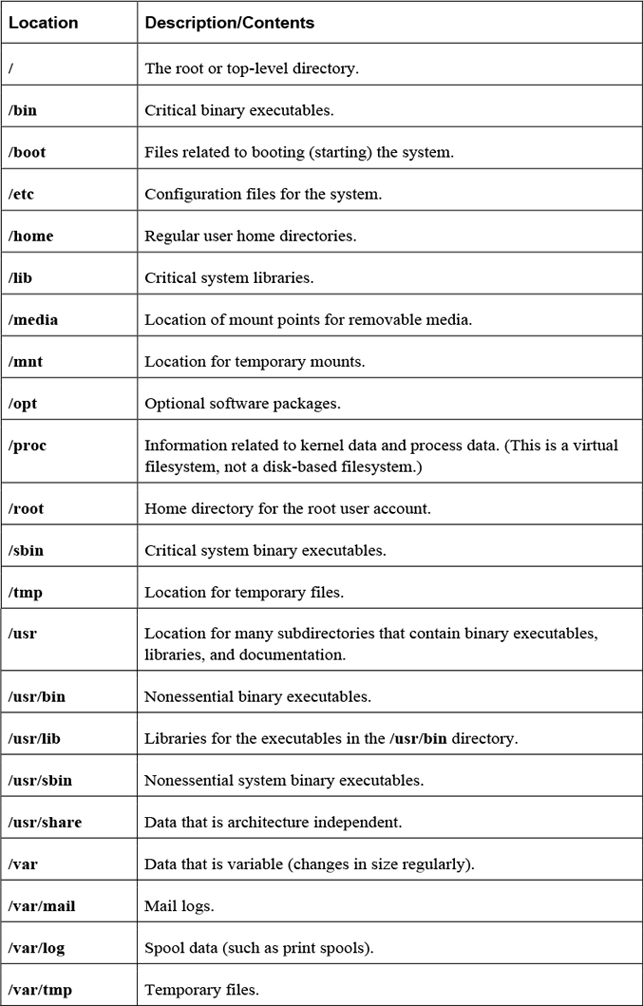

The Filesystem Hierarchy Standard (FHS) is a definition of where files and directories are supposed to be place on Unix and Linux operating systems. A summary of some of the more important locations is provided in Table 2-1.

The standard way of executing a shell command is to type the command at a command prompt and then press the Enter key. Here’s an example:

[student@localhost rc0.d]$ pwd /etc/rc0.d

Commands also accept options and arguments:

• An option is a predefined value that changes the behavior of a command. How the option changes the behavior of the command depends on the specific command.

• Typically options are a single character value that follow a hyphen (-) character, as in -a, -g, and -z. Often these single-character options can be combined together (for example, -agz). Some newer commands accept “word” options, such as --long or --time. Word options start with two hyphens.

• Arguments are additional information, such as a filename or user account name, that is provided to determine which specific action to take. The type of argument that is permitted depends on the command itself. For example, the command to remove a file from the system would accept a filename as an argument, whereas the command to delete a user account from the system would accept a user name as an argument.

• Unlike options, arguments do not start with a hyphen (or hyphens).

To execute a sequence of commands, separate each command with a semicolon and press the Enter key after the last command has been entered. Here’s an example:

[student@localhost ~]$ pwd ; date ; ls /home/student Fri Dec 2 00:25:03 PST 2016 book Desktop Downloads Music Public Templates class Documents hello.pl Pictures rpm Videos

The pwd (print working directory) command displays the shell’s current directory:

[student@localhost rc0.d]$ pwd /etc/rc0.d

To move the shell’s current directory to another directory, use the cd (change directory) command. The cd command accepts a single argument: the location of the desired directory. For example, to move to the /etc directory, you can execute the following command:

[student@localhost ~]$ cd /etc [student@localhost etc]$

The cd command is one of those “no news is good news” sort of commands. If the command succeeds, no output is displayed (however, note that the prompt has changed). If the command fails, an error will be displayed, as shown here:

[student@localhost ~]$ cd /etc bash: cd: nodir: No such file or directory [student@localhost ~]$

Security Highlight

For security reasons, users cannot cd into all directories. This will be covered in greater detail in Chapter 9, “File Permissions.”

When the argument you provide starts with the root directory symbol, it is considered to be an absolute path. An absolute path is used when you provide directions to where you want to go from a fixed location (the root directory). For example, you could type the following command:

cd /etc/skel

You can also give directions based on your current location. For example, if you are already in the /etc directory and want to go down to the skel directory, you could execute the cd skel command. In this case, the skel directory must be directly beneath the etc directory. This form of entering the pathname is called using a relative pathname.

If you think about it, you have given directions in one of these ways many times in the past. For example, suppose you had a friend in Las Vegas and you wanted to provide directions to your house in San Diego. You wouldn’t start providing directions from the friend’s house, but rather from a fixed location that you both are familiar with (like a commonly used freeway). But, if that same friend was currently at your house and wanted directions to a local store, you would provide directions from your current location, not the previously mentioned fixed location.

In Linux, there are a few special characters that represent directories to commands like the cd command:

• Two “dot” (period) characters (..) represent one level above the current directory. So, if the current directory is /etc/skel, the command cd .. would change the current directory to the /etc directory.

• One dot (.) represents the current directory. This isn’t very useful for the cd command, but it is handy for other commands when you want to say “the directory I am currently in.”

• The tilde character (~) represents the user’s home directory. Every user has a home directory (typically /home/username) where the user can store their own files. The cd ~ command will return you to your home directory.

The ls command is used to list files in a directory. By default, the current directory’s files are listed, as shown in the following example:

[student@localhost ~]$ ls Desktop Downloads Pictures Templates Documents Music Public Videos

As with the cd command, you can provide a directory argument using either an absolute or relative path to list files in another directory.

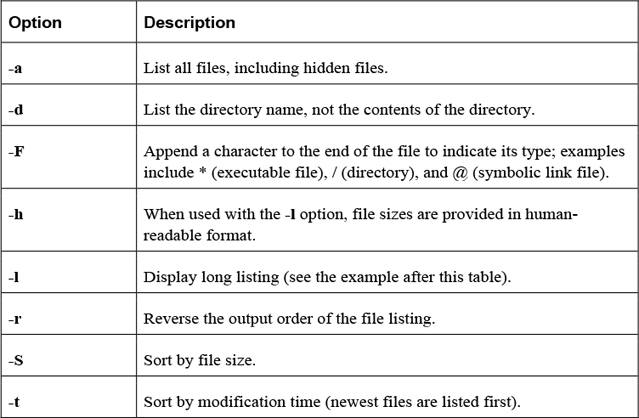

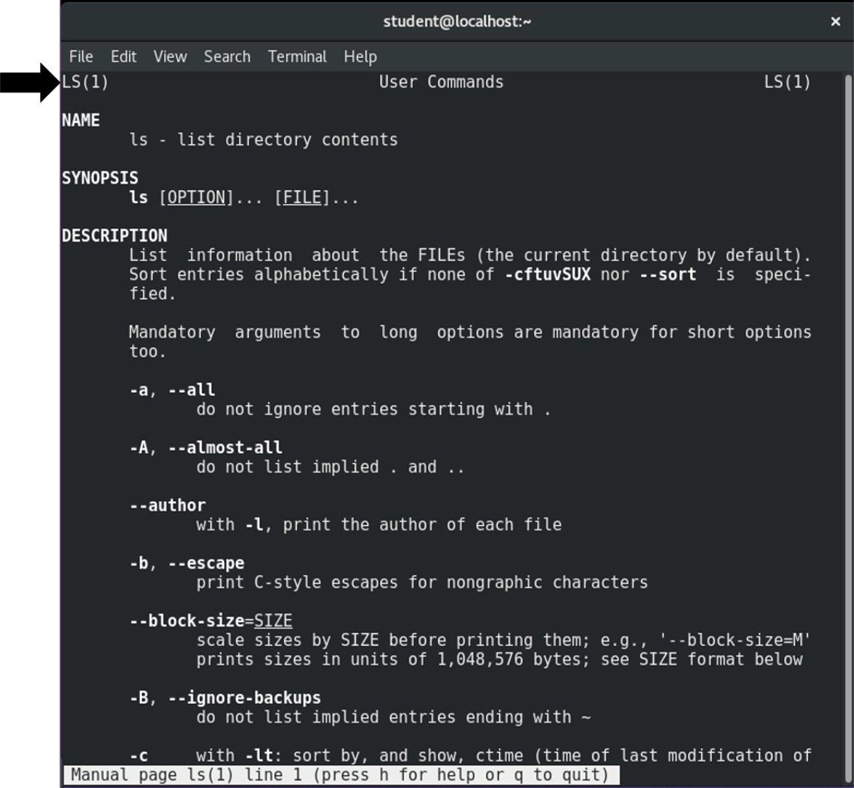

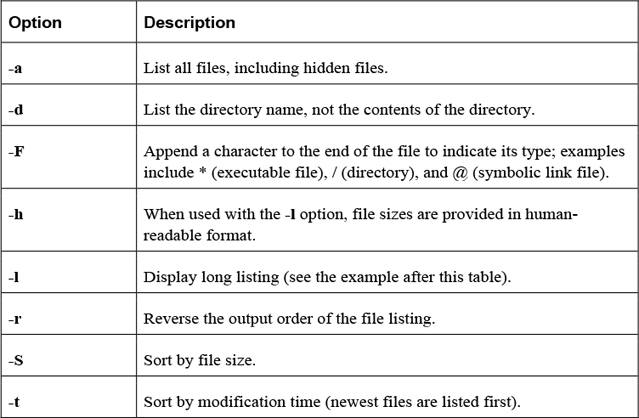

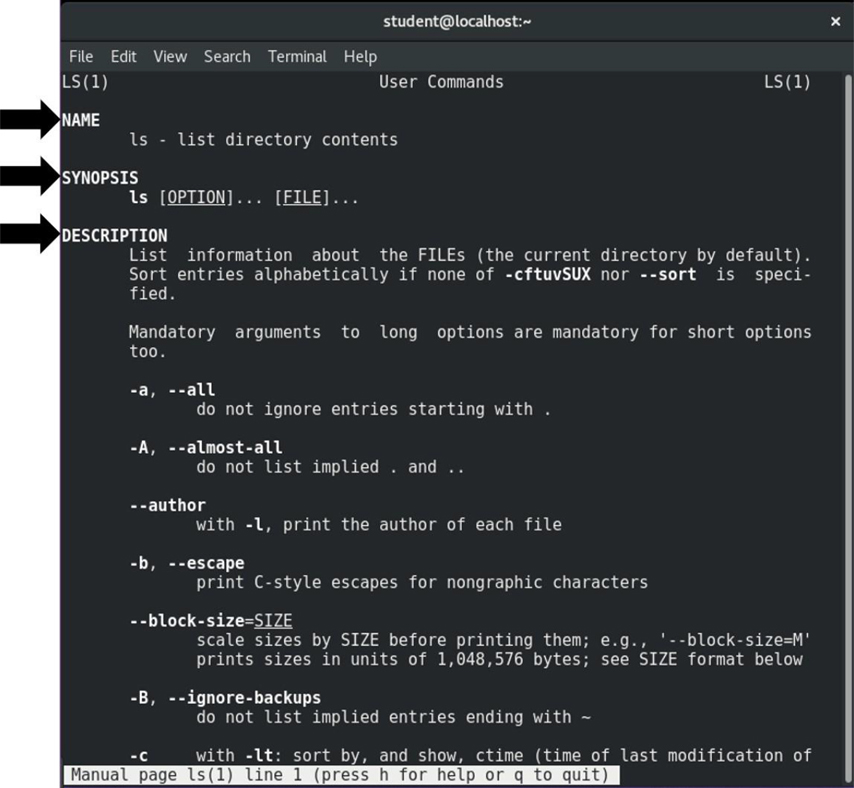

The ls command has many options. Some of the most important options are shown in Table 2-2.

What Could Go Wrong

In Linux, commands, options, filenames, and just about everything else is case sensitive. This means that if you try to execute the command ls -L, you will get different output (or an error message) than if you type the command ls -l.

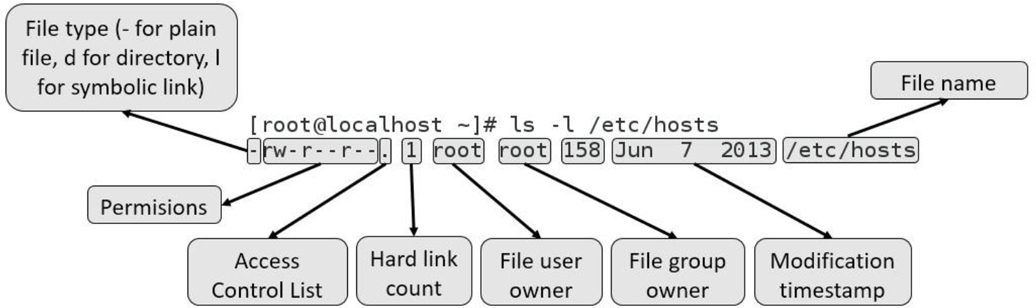

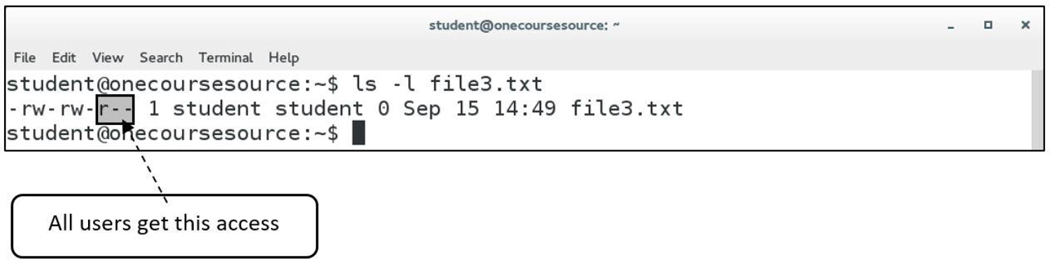

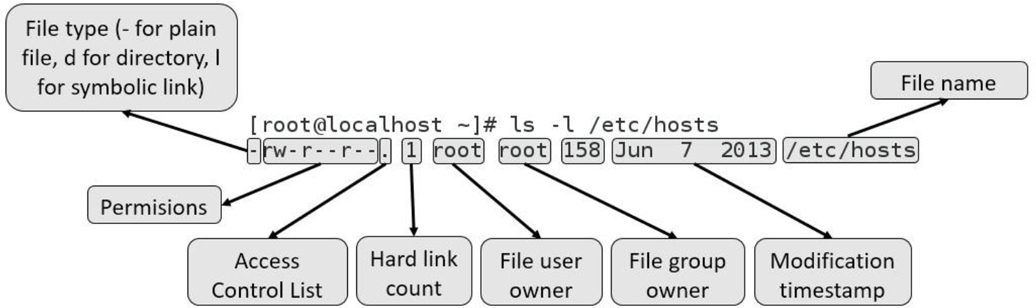

The output of the ls -l command includes one line per file, as demonstrated in Figure 2-2.

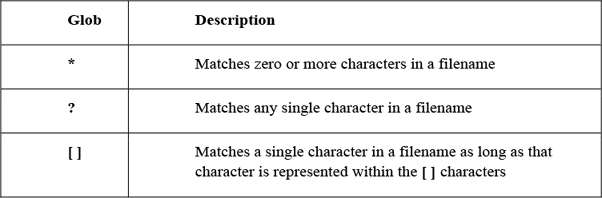

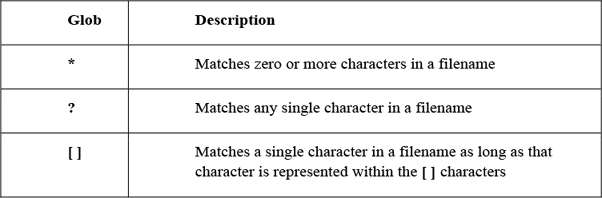

A file glob (also called a wildcard) is any character provided on the command line that represents a portion of a filename. The following globs are supported:

This example displays all files in the current directory that begin with the letter D:

[student@localhost ~]$ ls -d D* Desktop Documents Downloads

The next example displays all files in the current directory that are five characters long:

[student@localhost ~]$ ls -d ????? Music

The file command will report the type of contents in the file. The following commands provide some examples:

[student@localhost ~]$ file /etc/hosts /etc/hosts: ASCII text [student@localhost ~]$ file /usr/bin/ls /usr/bin/ls: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked (uses shared libs), for GNU/Linux 2.6.32, BuildID[sha1]=aa7ff68f13de25936a098016243ce57c3c982e06, stripped [student@localhost ~]$ file /usr/share/doc/pam-1.1.8/html/sag-author.html /usr/share/doc/pam-1.1.8/html/sag-author.html: HTML document, UTF-8 Unicode text, with very long lines

Why use the file command? The next few commands in this chapter are designed to work only on text files, such as the /etc/hosts file in the previous example. Nontext files shouldn’t be displayed with commands such as the less, tail, and head commands.

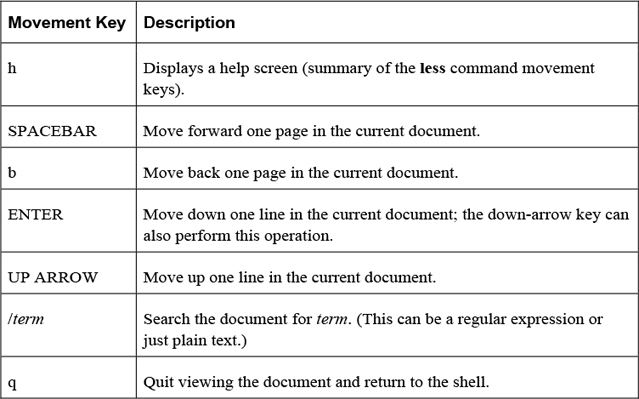

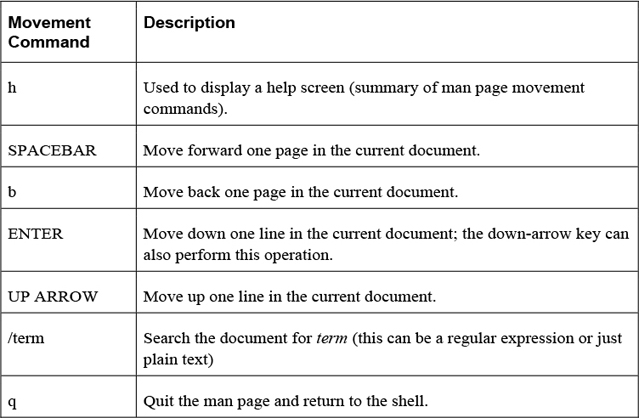

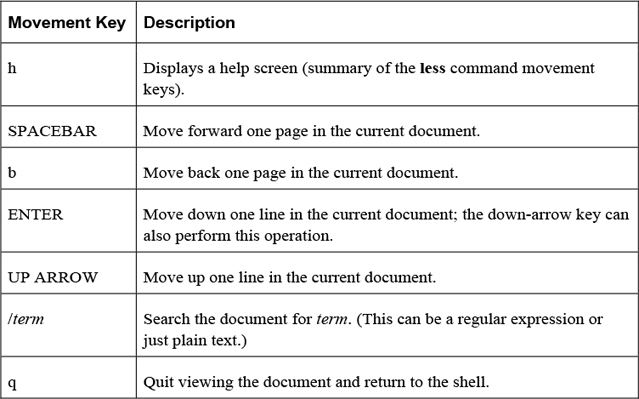

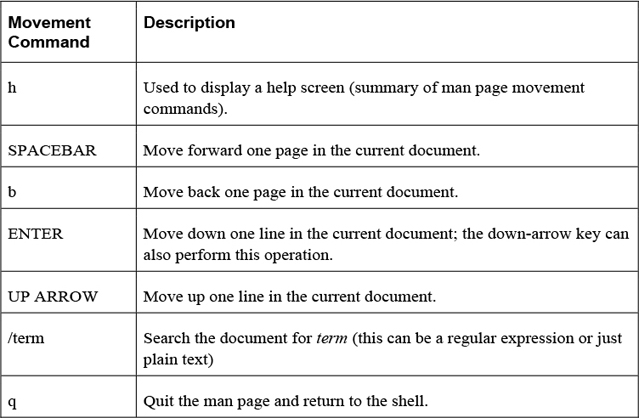

The less command is used to display large chunks of text data, pausing after displaying the first page of information. Keys on the keyboard allow the user to scroll through the document. Table 2-3 highlights the more useful movement keys:

Note

You may also see documentation regarding the more command. It uses many of the same movement options as the less command, but has fewer features.

The head command displays the top part of text data. By default, the top ten lines are displayed. Use the -n option to display a different number of lines:

[student@localhost ~]$ head -n 3 /etc/group root:x:0: bin:x:1:student daemon:x:2:

Security Highlight

The /etc/group file was purposefully chosen for this example. It is designed to hold group account information on the system and will be explored in detail in Chapter 6, “Managing Group Accounts.” It was included in this example to start getting you used to looking at system files, even if right now the contents of these files might not be clear.

The tail command displays the bottom part of text data. By default, the last ten lines are displayed. Use the -n option to display a different number of lines:

[student@localhost ~]$ tail -n 3 /etc/group slocate:x:21: tss:x:59: tcpdump:x:72:

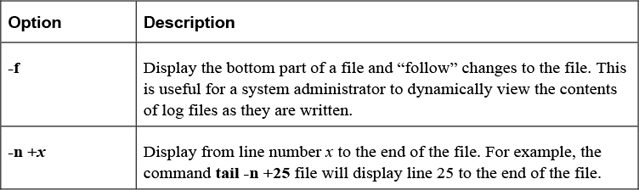

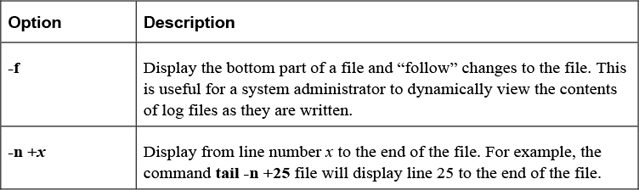

Important options of the tail command include those shown in Table 2-4.

Table 2-4 Options of the tail Command

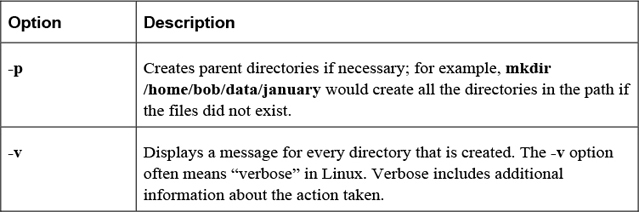

The mkdir command makes (creates) a directory.

Example:

mkdir test

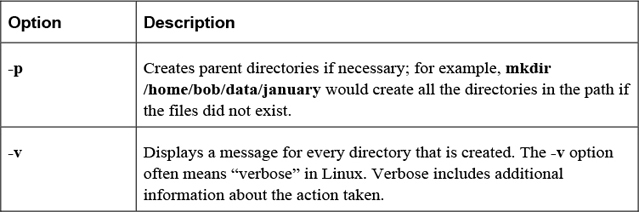

Important options of the mkdir command are shown in Table 2-5.

Table 2-5 Options of the mkdir Command

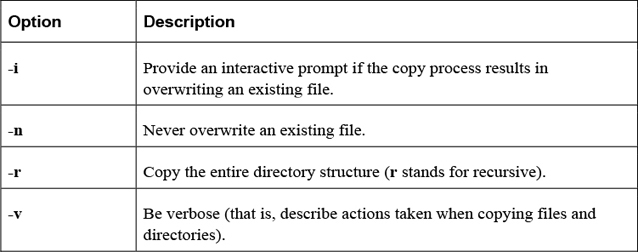

The cp command is used to copy files or directories. The syntax for this command is

cp [options] file|directory destination

where file|directory indicates which file or directory to copy. The destination is where you want the file or directory copied. The following example copies the /etc/hosts file into the current directory:

[student@localhost ~]$ cp /etc/hosts .

Note that the destination must be specified.

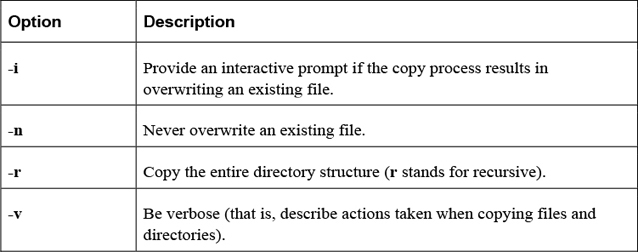

Table 2-6 provides some important options for the cp command.

Table 2-6 Options for the cp Command

The mv command will move or rename a file.

Example:

mv /tmp/myfile ~

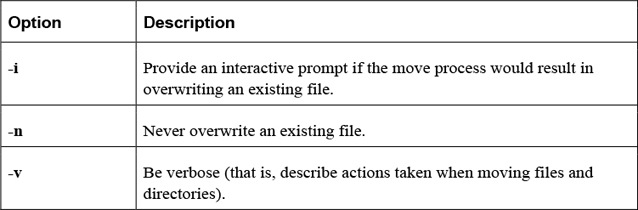

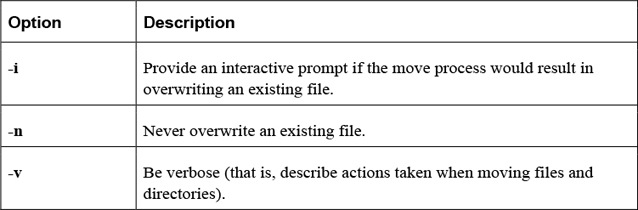

Important options include those shown in Table 2-7.

Table 2-7 Options for the mv Command

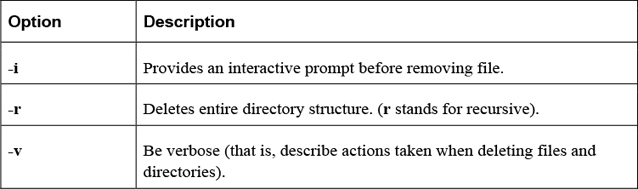

The rm command is used to remove (delete) files and directories.

Example:

rm file.txt

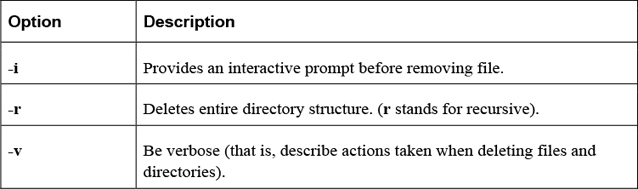

Important options include those shown in Table 2-8.

Table 2-8 Options for the rm Command

The rmdir command is used to remove (delete) empty directories. This command will fail if the directory is not empty (use rm -r to delete a directory and all the files within the directory).

Example:

rmdir data

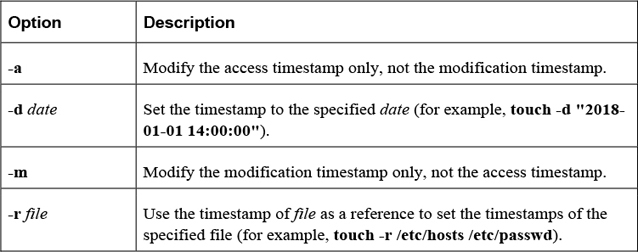

The touch command has two functions: to create an empty file and to update the modification and access timestamps of an existing file. To create a file or update an existing file’s timestamps to the current time, use the following syntax:

touch filename

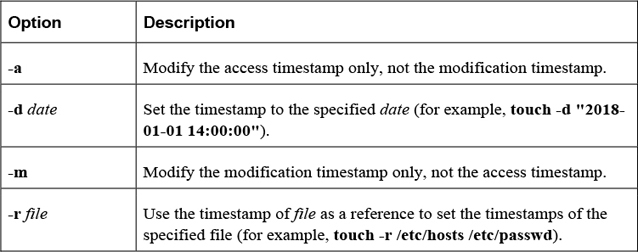

Important options include those shown in Table 2-9.

Table 2-9 Options for the touch Command

Security Highlight

The touch command is very useful for updating the timestamps of critical files for inclusion in automated system backups. You will learn more about system backups in Chapter 10, “Manage Local Storage: Essentials.”

The BASH shell provides many features that can be used to customize your working environment. This section focuses on these features.

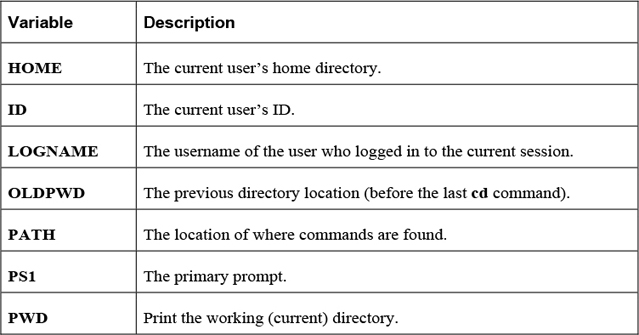

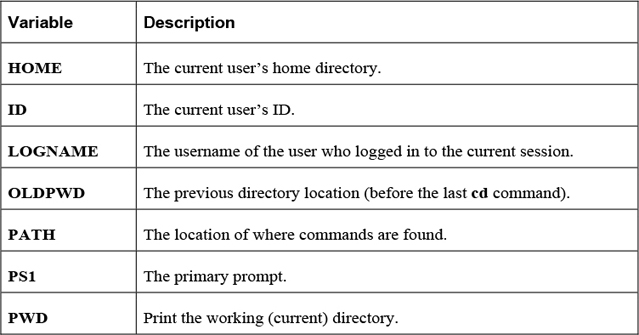

Shell variables are used to store information within the shell. This information is used to modify the behavior of the shell itself or external commands. Table 2-10 details some common useful shell variables.

Note

There are many shell variables in addition to those listed in the previous table. More details regarding the PATH and PS1 variables are provided later in this section of the chapter.

The echo command is used to display information. Typically it is used to display the value of variables.

Example:

[student@localhost ~]$ echo $HISTSIZE 1000

The echo command has only a few options. The most useful one is the -n option, which doesn't print a newline character at the end of the output.

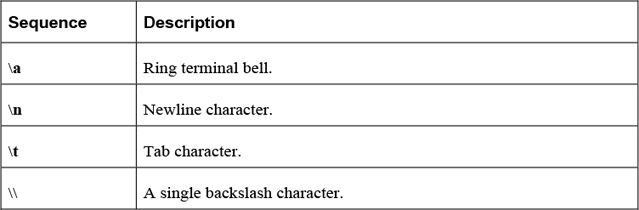

Some special characters sequences can be incorporated within an argument to the echo command. For example, the command echo "hello\nthere" will send the following output:

hello there

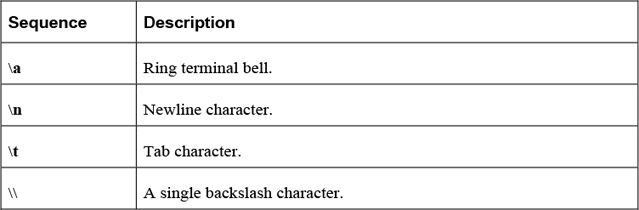

Table 2-11 describes some useful character sequences for the echo command.

Table 2-11 Character Sequences of the echo Command

Security Highlight

The echo command can offer valuable troubleshooting information when attempting to debug a program or a script because the user can ring the terminal bell at various points as the program executes, to denote to the user that various points in the program were reached successfully.

The set command displays all shell variables and values when executed with no arguments. To see all shell variables, use the set command, as demonstrated here:

[student@localhost ~ 95]$ set | head -n 5 ABRT_DEBUG_LOG=/dev/null AGE=25 BASH=/bin/bash BASHOPTS=checkwinsize:cmdhist:expand_aliases:extglob:extquote:force_fignore: histappend:interactive_comments:progcomp:promptvars:sourcepath BASH_ALIASES=()

Note

The | head -n 5 part of the previous command means “send the output of the set command into the head command as input and only display the first five lines of this output.” This is a process called redirection, which will be covered in detail in a later section of this chapter. It was included in the previous example because the output of the set command would end up taking several pages of this book.

The set command can also be used to modify the behavior of the shell. For example, using a variable that currently isn’t assigned a value normally results in displaying a “null string” or no output. Executing the command set -u will result in an error message when undefined variables are used:

[student@localhost ~]$ echo $NOPE [student@localhost ~]$ set -u [student@localhost ~]$ echo $NOPE bash: NOPE: unbound variable

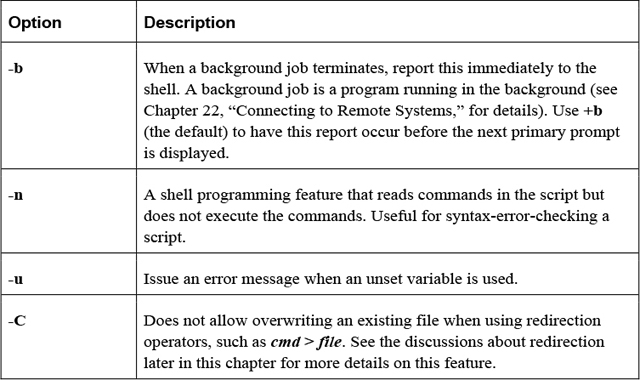

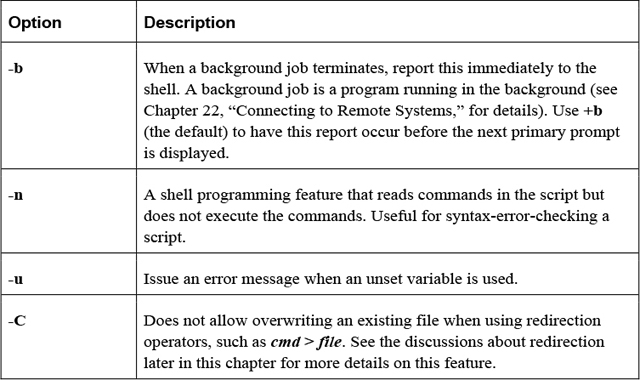

Table 2-12 provides some additional useful set options.

Table 2-12 Options for the set Command

Use the unset command to remove a variable from the shell (for example, unset VAR).

The PS1 variable defines the primary prompt, often using special character sequences (\u = current user’s name, \h = host name, \W = current directory). Here’s an example:

[student@localhost ~]$ echo $PS1 [\u@\h \W]\$

Note that variables are defined without a dollar sign character but are referenced using the dollar sign character:

[student@localhost ~]$ PS1="[\u@\h \W \!]\$ " [student@localhost ~ 93]$ echo $PS1 [\u@\h \W \!]$

Most commands can be run by simply typing the command and pressing the Enter key:

[student@localhost ~]# date Thu Dec 1 18:48:26 PST 2016

The command is “found” by using the PATH variable. This variable contains a comma-separated list of directory locations:

[student@localhost ~]$ echo $PATH /usr/local/bin:/usr/local/sbin:/usr/bin:/usr/sbin:/bin:/sbin: /home/student/.local/bin:/home/student/bin

This “defined path” is searched in order. So, when the previous date command was executed, the BASH shell first looked in the /usr/local/bin directory. If the date command is located in this directory, it is executed; otherwise, the next directory in the PATH variable is checked. If the command isn’t found in any of these directories, an error is displayed:

[student@localhost ~]$ xeyes bash: xeyes: command not found...

Security Highlight

In some cases when a command isn’t found, you may see a message like the following:

Install package 'xorg-x11-apps' to provide command 'xeyes'? [N/y]

This is a result of when the command you are trying to run isn’t on the system at all, but can be installed via a software package. For users who use Linux at home or in a noncommercial environment, this can be a useful feature, but if you are working on a production server, you should always carefully consider any software installation.

To execute a command that is not in the defined path, use a fully qualified path name, as shown here:

[student@localhost ~]$ /usr/xbin/xeyes

To add a directory to the PATH variable, use the following syntax:

[student@localhost ~]$ PATH="$PATH:/path/to/add"

The value to the right of = sign ("$PATH:/path/to/add") first will return the current value of the PATH variable and then append a colon and a new directory. So, if the PATH variable was set to /usr/bin:/bin and the PATH="$PATH:/opt" command was executed, then the result would be to assign the PATH variable to /usr/bin:/bin:/opt.

Security Highlight

Adding "." (the current directory) to the PATH variable poses a security risk. For example, suppose you occasionally mistype the ls command by typing sl instead. This could be exploited by someone who creates an sl shell script (program) in a common directory location (for example, the /tmp directory is a common place for all users to create files). With "." in your PATH variable, you could end up running the bogus sl “command,” which could comprise your account or the operating system (depending on what commands the hacker placed in the script).

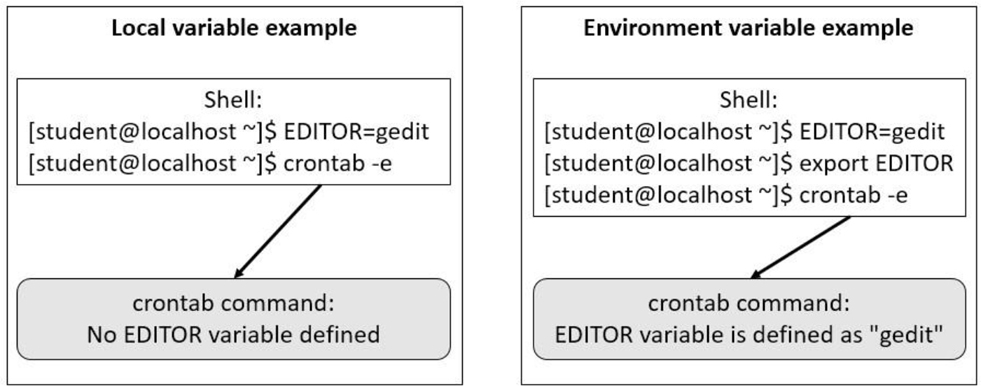

When a variable is initially created, it is only available to the shell in which it was created. When another command is run within that shell, the variable is not “passed in to” that other command.

To pass variables and their values in to other commands, convert an existing local variable to an environment variable with the export command, like so:

[student@localhost ~]$ echo $NAME Sarah [student@localhost ~]$ export NAME

If the variable doesn’t already exist, the export command can create it directly as an environment variable:

[student@localhost ~]$ export AGE=25

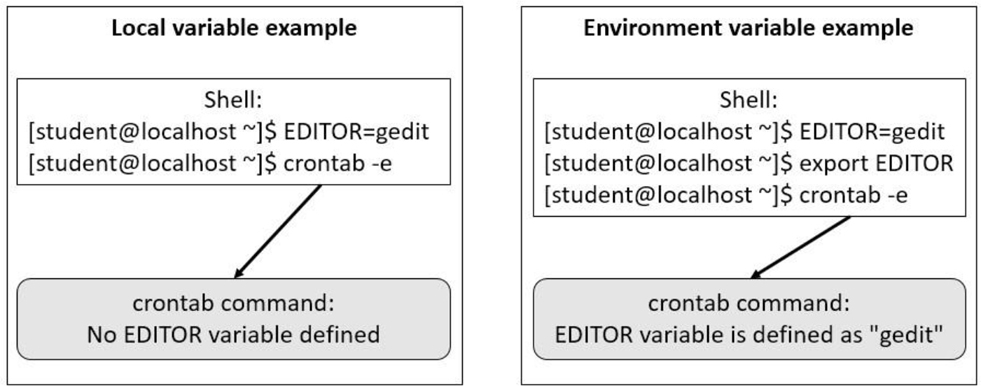

When a variable is converted into an environment variable, all subprocesses (commands or programs started by the shell) will have this variable set. This is useful when you want to change the behavior of a process by modifying a key variable.

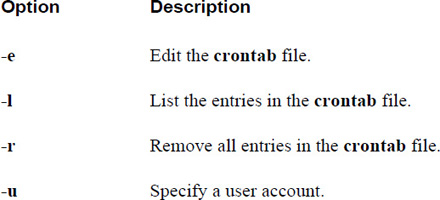

For example, the crontab -e command allows you to edit your crontab file (a file that allows you to schedule programs to run sometime in the future; see Chapter 14, “Crontab and at,” for details). To choose the editor that the crontab command will use, create and export the EDITOR variable: export EDITOR=gedit.

See Figure 2-3 for a visual example of local versus environment variables.

Figure 2-3 Local versus Environment Variables

The export command can also be used to display all environment variables, like so:

export -p

The env command displays environment variables in the current shell. Local variables are not displayed when the env command is executed.

Another use of the env command is to temporarily set a variable for the execution of a command.

For example, the TZ variable is used to set the timezone in a shell. There may be a case when you want to temporarily set this to a different value for a specific command, such as the date command shown here:

[student@localhost ~]# echo $TZ [student@localhost ~]# date Thu Dec 1 18:48:26 PST 2016 [student@localhost ~]# env TZ=MST7MDT date Thu Dec 1 19:48:31 MST 2016 [student@localhost ~]# echo $TZ [student@localhost ~]#

To unset a variable when executing a command, use the --unset=VAR option (for example, env --unset=TZ date).

When a user logs in to the system, a login shell is started. When a user starts a new shell after login, it is referred to as a non-login shell. In each case, initialization files are used to set up the shell environment. Which initialization files are executed depends on whether the shell is a login shell or a non-login shell.

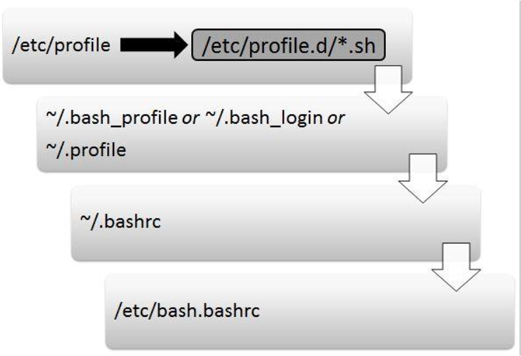

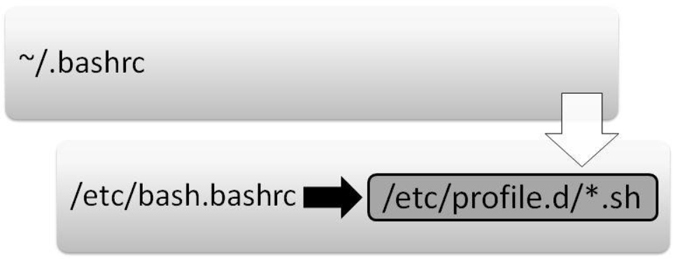

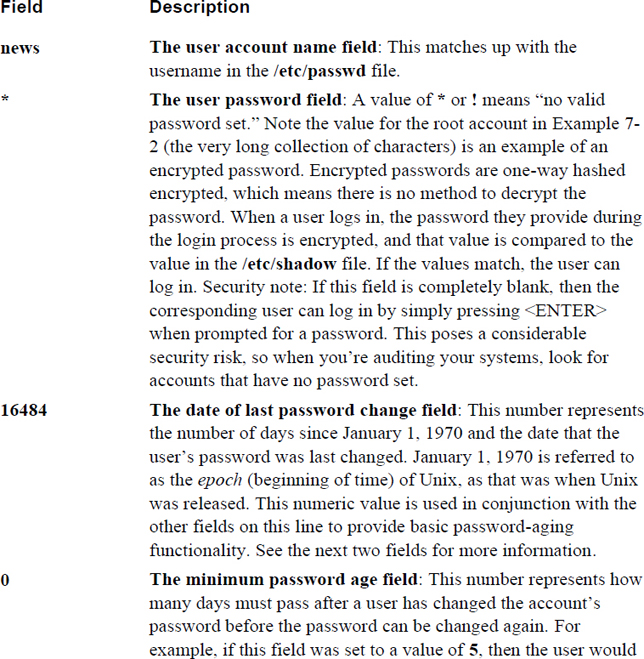

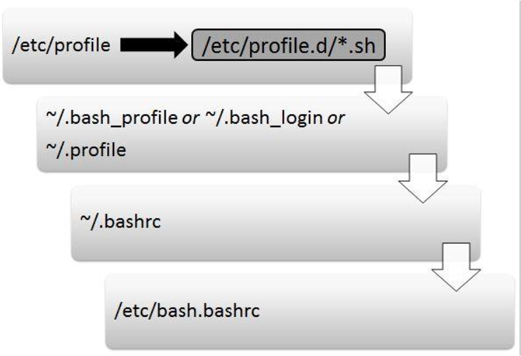

Figure 2-4 demonstrates which initialization files are executed when the user logs in to the system.

Figure 2-4 Initialization Files Executed When the User Logs In to the System

The following is an explanation of Figure 2-4:

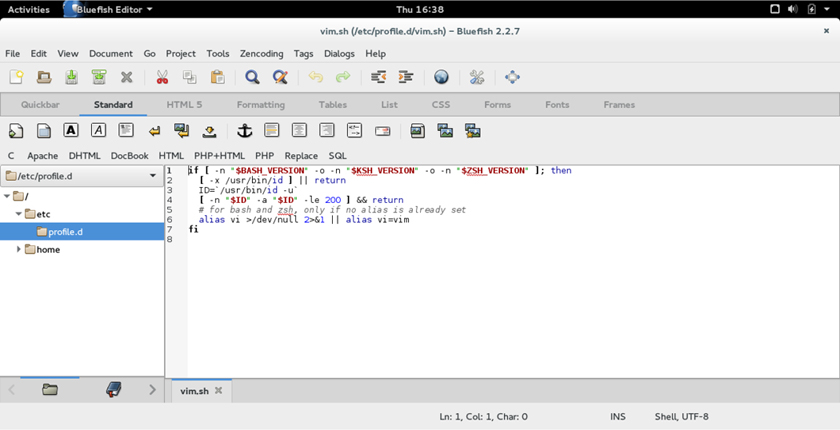

• The first initialization file that is executed when a user logs in is the /etc/profile file. On most Linux platforms, this script includes code that executes all the initialization files in the /etc/profile.d directory that end in “.sh”. The purpose of the /etc/profile file is to serve as a place for system administrators to put code that will execute every time a BASH shell user logs in (typically login messages and environment variables definitions).

• After the /etc/profile file is executed, the login shell looks in the user’s home directory for a file named ~/.bash_profile. If it’s found, the login shell executes the code in this file. Otherwise, the login shell looks for a file named ~/.bash_login. If it’s found, the login shell executes the code in this file. Otherwise, the login shell looks for a file named ~/.profile and executes the code in this file. The purpose of these files is to serve as a place where each user can put code that will execute every time that specific user logs in (typically environment variables definitions).

• The next initialization file executed is the ~/.bashrc script. The purpose of this file is to serve as a place where each user can put code that will execute every time the user opens a new shell (typically alias definitions).

• The next initialization file executed is the /etc/bash.bashrc script. The purpose of this file is to serve as a place where system administrators can put code that will execute every time the user opens a new shell (typically alias definitions).

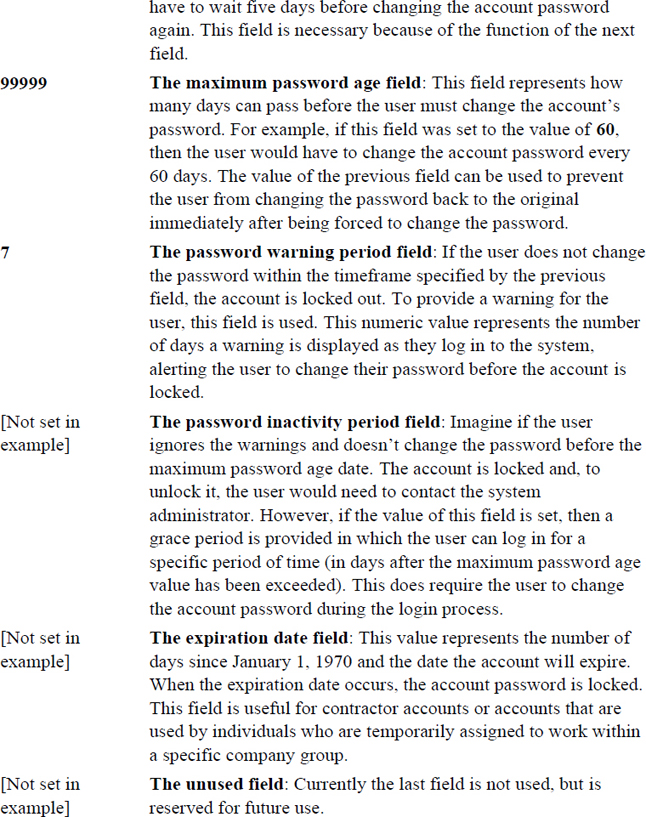

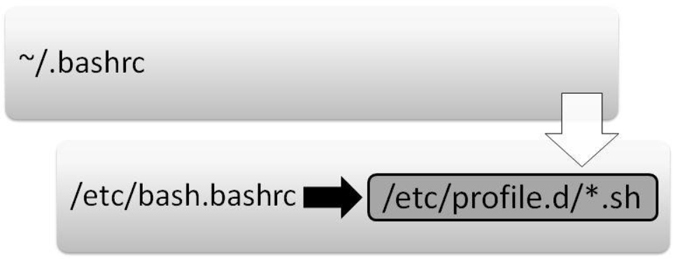

Figure 2-5 demonstrates which initialization files are executed when the user opens a new shell.

Figure 2-5 Initialization Files Executed When the User Starts a Non-Login Shell

The following is an explanation of Figure 2-5:

• The first initialization file that is executed when a user opens a non-login shell is the ~/.bashrc script. The purpose of this file is to serve as a place where each user can put code that will execute every time that user opens a new shell (typically alias definitions).

• The next initialization file executed is the /etc/bash.bashrc script. On most Linux platforms, this script includes code that executes all the initialization files in the /etc/profile.d directory that end in “.sh”. The purpose of these initialization files is to serve as a place where system administrators can put code that will execute every time the user opens a new shell (typically alias definitions).

An alias is a shell feature that allows a collection of commands to be executed by issuing a single “command.” Here’s how to create an alias:

[student @localhost ~]$ alias copy="cp"

And here’s how to use an alias:

[student @localhost ~]$ ls file.txt [student @localhost ~]$ copy /etc/hosts . [student @localhost ~]$ ls file.txt hosts

To display all aliases, execute the alias command with no arguments. To unset an alias, use the unalias command as shown in Example 2-1.

Example 2-1 Using unalias Command to Unset an Alias

[student @localhost ~]$ alias alias copy='cp' alias egrep='egrep --color=auto' alias fgrep='fgrep --color=auto' alias grep='grep --color=auto' alias l='ls -CF' alias la='ls -A' alias ll='ls -alF' [student @localhost ~]$ unalias copy [student @localhost ~]$ alias alias egrep='egrep --color=auto' alias fgrep='fgrep --color=auto' alias grep='grep --color=auto' alias l='ls -CF' alias la='ls -A' alias ll='ls -alF'

Each shell keeps a list of previously executed commands in a memory-based history list. This list can be viewed by executing the history command.

The history command displays the contents of the history list. This output can be quite large, so often a numeric value is given to limit the number of commands displayed. For example, the following history command lists the last five commands in the history list:

[student@localhost ~]$ history 5 83 ls 84 pwd 85 cat /etc/passwd 86 clear 87 history 5

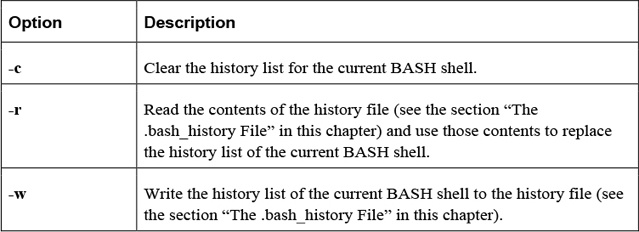

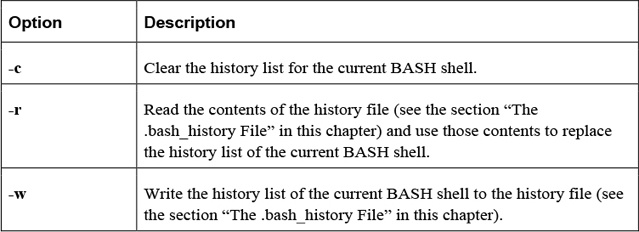

Table 2-13 shows some useful options for the history command.

Table 2-13 Options for the history Command

To execute a command in the history list, type ! followed directly by the command you want to execute. For example, to execute command number 84 (the pwd command in the previous example), enter the following:

[student@localhost ~]$ !84 pwd /home/student

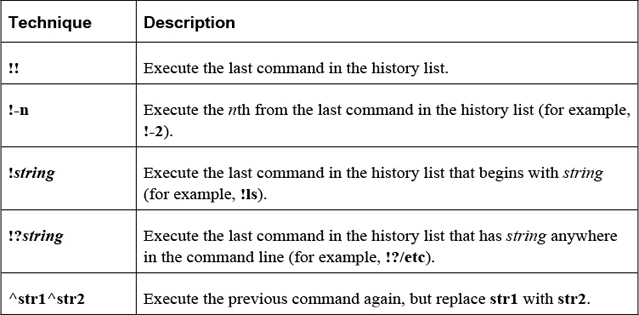

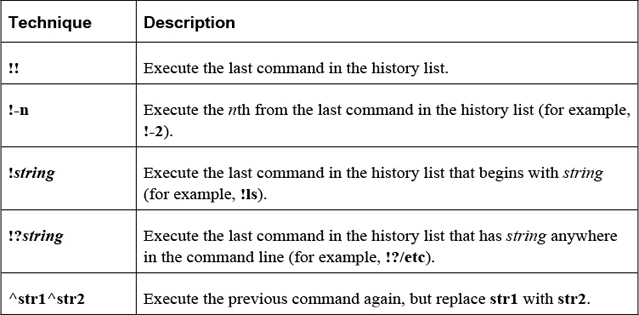

Table 2-14 provides some additional techniques for executing previous commands.

Table 2-14 Techniques for Executing Commands

Here’s an example of using ^str1^str2:

[student@localhost ~]$ ls /usr/shara/dict ls: cannot access /usr/shara/dict: No such file or directory [student@localhost ~]$ ^ra^re ls /usr/share/dict linux.words words

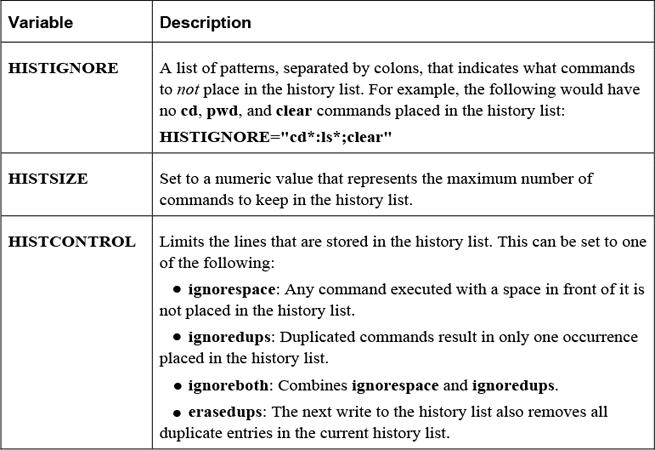

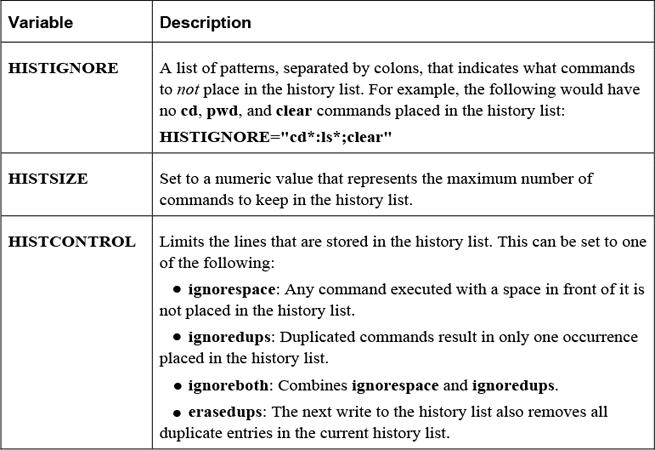

Several variables can affect how information is stored in the history list, some of which are shown in Table 2-15.

Table 2-15 Variables Affecting Storage in the History List

When a user logs off the system, the current history list is written automatically to the user’s .bash_history file. This is typically stored in the user’s home directory (~/.bash_history), but the name and location can be changed by modifying the HISTFILE variable.

How many lines are stored in the .bash_history file is determined by the value of the HISTFILESIZE variable.

Security Highlight

The history command can pose a security risk because any Linux system that is not secured with a login screen and password-protected screensaver is susceptible to anyone having the credentials used to access the system and files simply by entering the history command and reading or copying the results to a file for later use. Always use a password-protected screensaver set for a short inactivity prompt to prevent this from happening. Clearing the history or using the HISTIGNORE variable to denote login information are additional security practices to prevent the use of authentication credentials found in past commands by others.

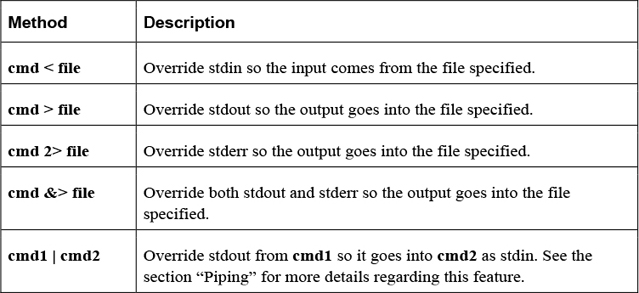

Each command is able to send two streams of output (standard output and standard error) and can accept one stream of data (standard input). In documentation, these terms can also be described as follows:

• Standard output = stdout or STDOUT

• Standard error = stderr or STDERR

• Standard input = stdin or STDIN

By default, stdout and stderr are sent to the terminal window, whereas stdin comes from keyboard input. In some cases, you want to change these locations, and this is accomplished by a process called redirection.

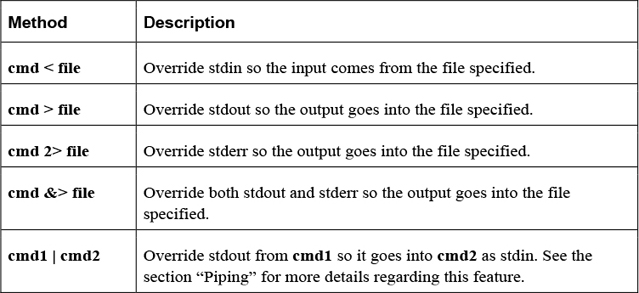

Table 2-16 describes the methods used to perform redirection.

Table 2-16 Methods for Redirection

In the following example, stdout of the cal program is sent to a file named month:

[student@localhost ~]$ cal > month

It is common to redirect both stdout and stderr into separate files, as demonstrated in the next example:

[student@localhost ~]$ find /etc -name "*.cfg" -exec file {} \;

> output 2> error

Redirecting stdin is fairly rare because most commands will accept a filename as a regular argument; however, the tr command, which performs character translations, requires redirecting stdin:

[student@localhost ~]$ cat /etc/hostname localhost [student@localhost ~]$ tr 'a-z' 'A-Z' < /etc/hostname LOCALHOST

The process of piping (so called because the | character is referred to as a “pipe”) the output of one command to another command results in a more powerful command line. For example, the following takes the standard output of the ls command and sends it into the grep command to filter files that were changed on April 16th:

[student@localhost ~]$ ls -l /etc | grep "Apr 16" -rw-r--r-- 1 root 321 Apr 16 2018 blkid.conf drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Apr 16 2018 fstab.d

In Example 2-2, lines 41–50 of the copyright file are displayed.

Example 2-2 Lines 41–50 of the Copyright File

[student@localhost ~]$ head -50 copyright | tail

b) If you have received a modified Vim that was distributed as

mentioned under a) you are allowed to further distribute it

unmodified, as mentioned at I). If you make additional changes

the text under a) applies to those changes.

c) Provide all the changes, including source code, with every

copy of the modified Vim you distribute. This may be done in

the form of a context diff. You can choose what license to use

for new code you add. The changes and their license must not

restrict others from making their own changes to the official

version of Vim.

d) When you have a modified Vim which includes changes as

mentioned

You can add additional commands, as demonstrated in Example 2-3, where the output of the tail command is sent to the nl command (which numbers the lines of output).

Example 2-3 Output of tail Command Is Sent to the nl Command

[student@localhost ~]$ head -50 copyright | tail | nl 1 b) If you have received a modified Vim that was distributed as 2 mentioned under a) you are allowed to further distribute it 3 unmodified, as mentioned at I). If you make additional changes 4 the text under a) applies to those changes. 5 c) Provide all the changes, including source code, with every 6 copy of the modified Vim you distribute. This may be done in 7 the form of a context diff. You can choose what license to use 8 for new code you add. The changes and their license must not 9 restrict others from making their own changes to the official 10 version of Vim. 11 d) When you have a modified Vim which includes changes as 12 mentioned

Note that the order of execution makes a difference. In Example 2-3, the first 40 lines of the copyright file are sent to the tail command. Then the last ten lines of the first 40 lines are sent to the nl command for numbering. Notice the difference in output when the nl command is executed first, as shown in Example 2-4.

Example 2-4 Executing the nl Command First

[student@localhost ~]$ nl copyright | head -50 | tail 36 b) If you have received a modified Vim that was distributed as 37 mentioned under a) you are allowed to further distribute it 38 unmodified, as mentioned at I). If you make additional changes 39 the text under a) applies to those changes. 40 c) Provide all the changes, including source code, with every 41 copy of the modified Vim you distribute. This may be done in 42 the form of a context diff. You can choose what license to use 43 for new code you add. The changes and their license must not 44 restrict others from making their own changes to the official 45 version of Vim. 45 d) When you have a modified Vim which includes changes as 47 mentioned

To take the output of one command and use it as an argument to another command, place the command within the $( ) characters. For example, the output of the date and pwd commands is sent to the echo command as arguments:

[student@localhost ~]$ echo "Today is $(date) and you are in the $(pwd) directory" Today is Tue Jan 10 12:42:02 UTC 2018 and you are in the /home/student directory

As previously mentioned, there are thousands of Linux commands. The commands covered in this section are some of the more advanced commands you are likely to use on a regular basis.

The find command will search the live filesystem for files and directories using different criteria. Here’s the format of the command:

find [options] starting_point criteria action

The starting_point is the directory where the search will start. The criteria is what to search for, and the action is what to do with the results.

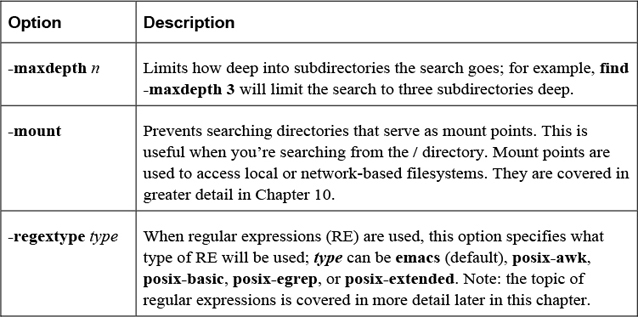

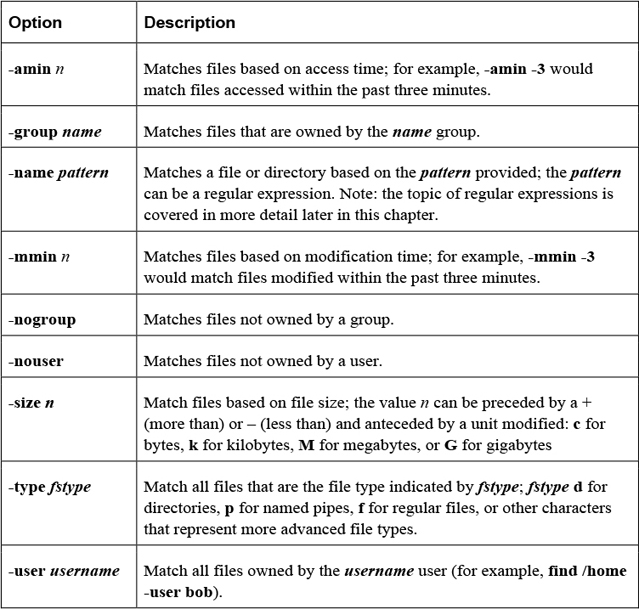

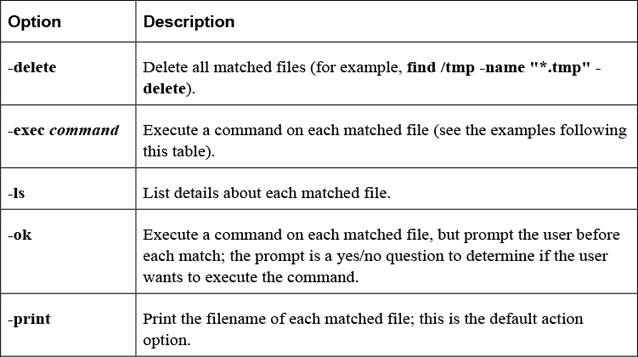

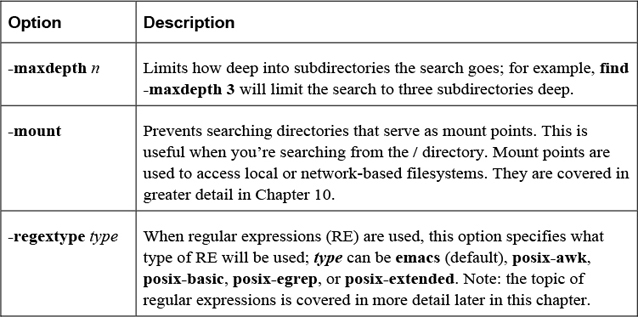

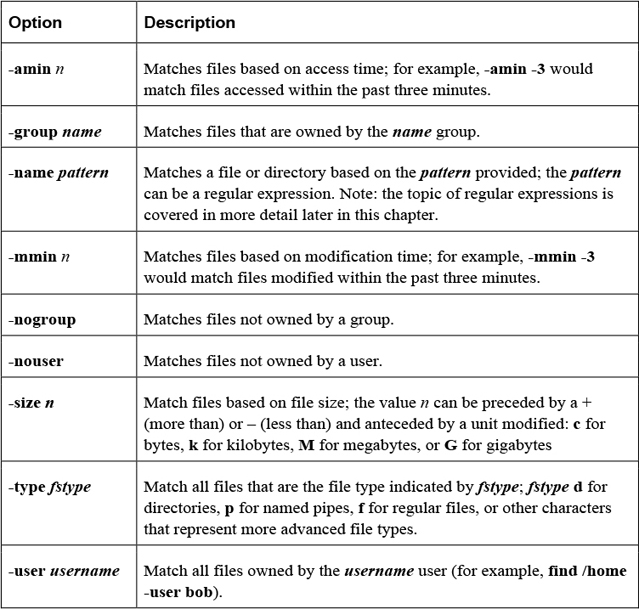

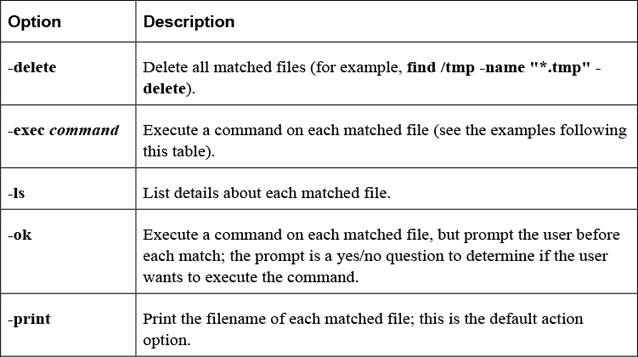

The options shown in Table 2-17 are designed to modify how the find command behaves.

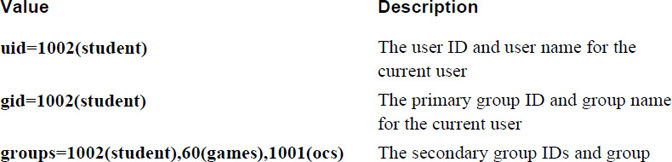

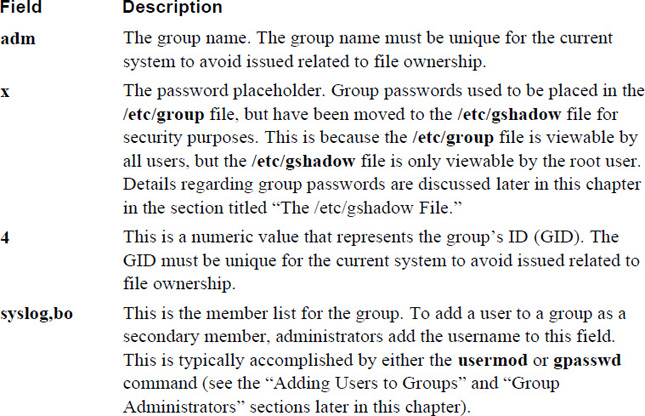

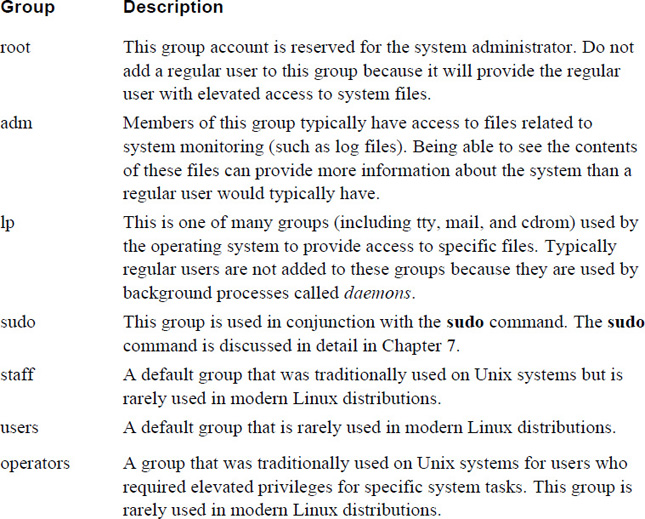

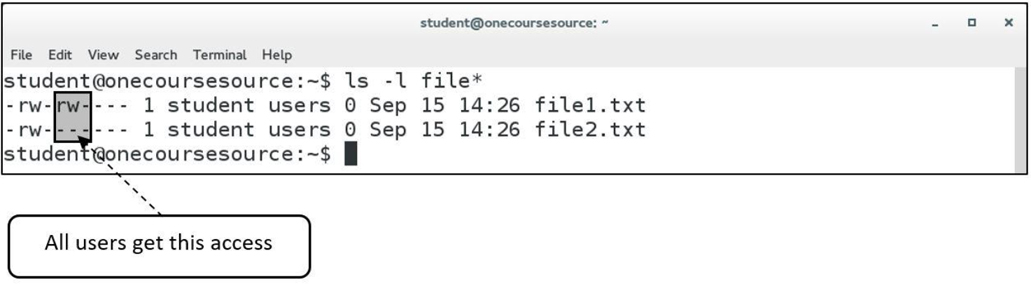

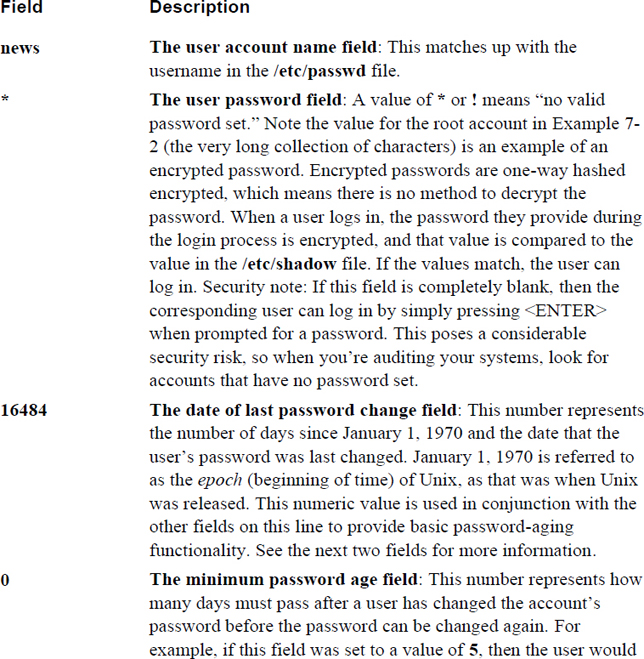

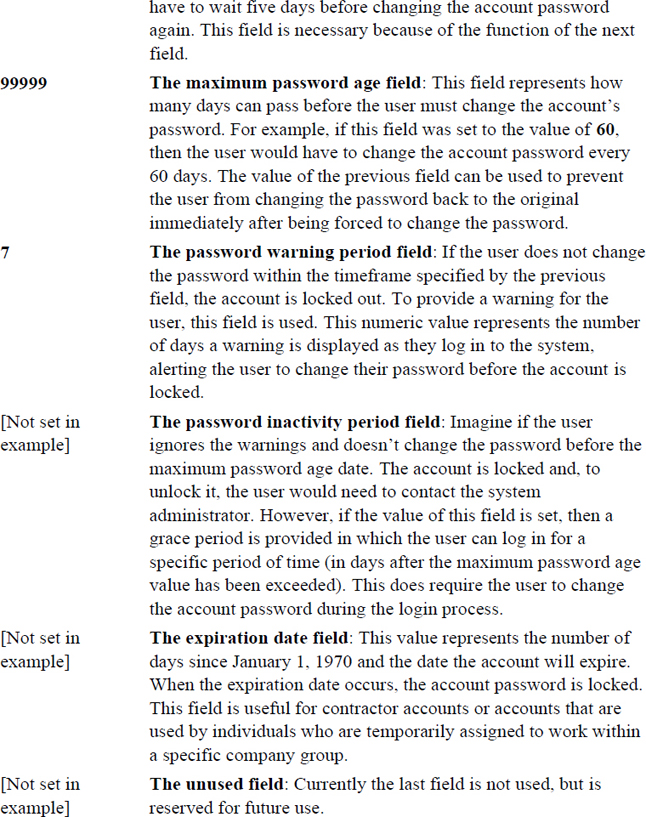

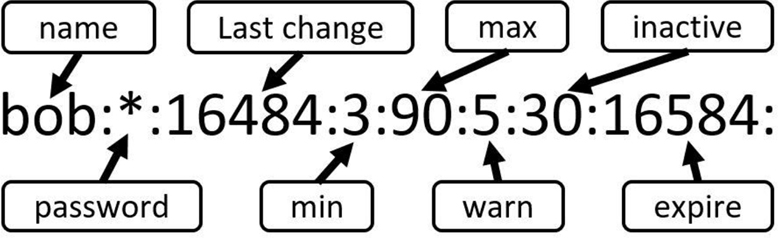

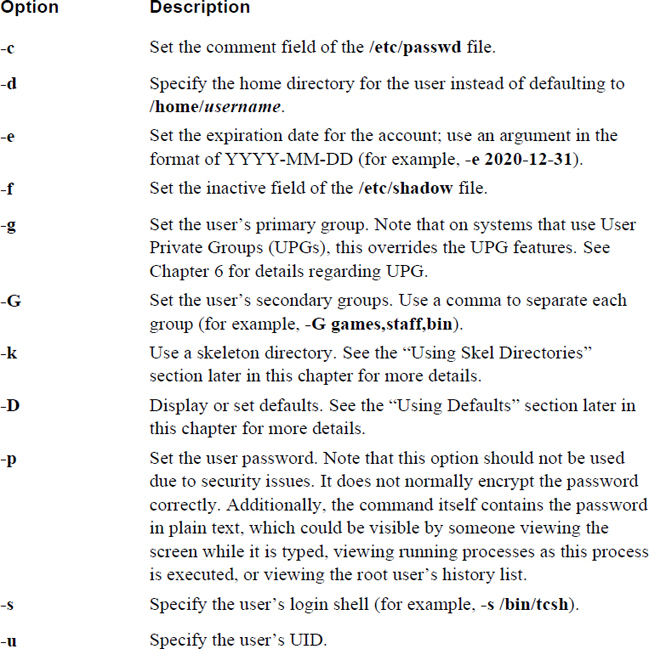

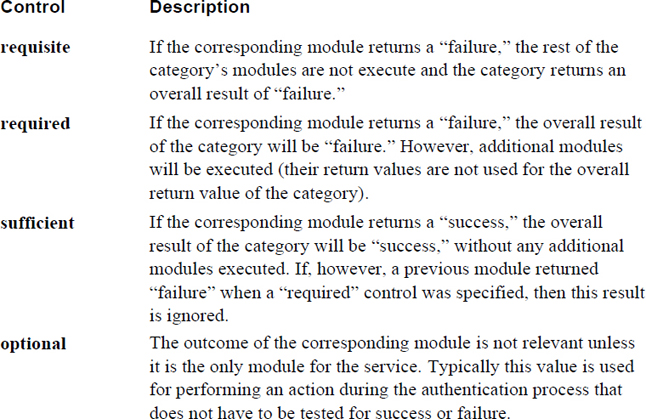

Table 2-17 Options for the find Command