Chapter 1 Distributions and Key Components

Before you start learning about all the features and capabilities of Linux, it would help to get a firm understanding of what Linux is, including what the major components are of a Linux operating system. In this first chapter, you learn about some of the essential concepts of Linux. You discover what a distribution is and how to pick a distribution that best suits your needs. You are also introduced to the process of installing Linux, both on a bare-metal system and in a virtual environment.

After reading this chapter and completing the exercises, you will be able to do the following:

Describe is the various parts of Linux

Identify the major components that make up the Linux operating system

Describe different types of Linux distributions

Identify the steps for installing Linux

Introducing Linux

Linux is an operating system, much like Microsoft Windows. However, this is a very simplistic way of defining Linux. Technically, Linux is a software component called the kernel, and the kernel is the software that controls the operating system.

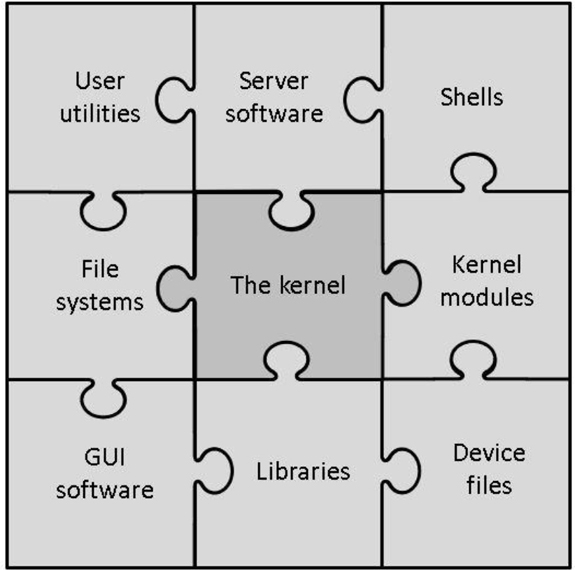

By itself, the kernel doesn’t provide enough functionality to provide a full operating system. In reality, many different components are brought together to define what IT professionals refer to as the Linux operating system, as shown in Figure 1-1.

Figure 1-1 The Components of the Linux Operating System

It is important to note that not all the components described in Figure 1-1 are always required for a Linux operating system. For example, there is no need for a graphical user interface (GUI). In fact, on Linux server systems, the GUI is rarely installed because it requires additional hard drive space, CPU cycles, and random access memory (RAM) usage. Also, it could pose a security risk.

Security Highlight

You may wonder how GUI software could pose a security risk. In fact, any software component poses a security risk because it is yet another part of the operating system that can be compromised. When you set up a Linux system, always make sure you only install the software required for that particular use case.

The pieces of the Linux operating system shown in Figure 1-1 are described in the following list:

• User utilities: Software that is used by users. Linux has literally thousands of programs that either run within a command line or GUI environment. Many of these utilities will be covered throughout this book.

• Server software: Software that is used by the operating system to provide some sort of feature or access, typically across a network. Common examples include a file-sharing server, a web server that provides access to a website, and a mail server.

• Shells: To interact with a Linux operating system via the command line, you need to run a shell program. Several different shells are available, as discussed later in this chapter.

• File systems: As with an operating system, the files and directories (aka folders) are stored in a well-defined structure. This structure is called a file system. Several different file systems are available for Linux. Details on this topic are covered in Chapter 10, “Manage Local Storage: Essentials,” and Chapter 11, “Manage Local Storage: Advanced Features.”

• The kernel: The kernel is the component of Linux that controls the operating system. It is responsible for interacting with the system hardware as well as key functions of the operating system.

• Kernel modules: A kernel module is a program that provides more features to the kernel. You many hear that the Linux kernel is a modular kernel. As a modular kernel, the Linux kernel tends to be more extensible, secure, and less resource intensive (in other words, it’s lightweight).

• GUI software: Graphical user interface (GUI) software provides “window-based” access to the Linux operating system. As with command-line shells, you have a lot of options when it comes to picking a GUI for a Linux operating system. GUI software is covered in more detail later in this chapter.

• Libraries: This is a collection of software used by other programs to perform specific tasks. Although libraries are an important component of the Linux operating system, they won’t be a major focus of this book.

• Device files: On a Linux system, everything can be referred to as a file, including hardware devices. A device file is a file that is used by the system to interact with a device, such as a hard drive, keyboard, or network card.

Linux Distributions

The various bits of software that make up the Linux operating system are very flexible. Additionally, most of the software is licensed as “open source,” which means the cost to use this software is often nothing. This combination of features (flexible and open source) has given rise to a large number of Linux distributions.

A Linux distribution (also called a distro) is a specific implementation of a Linux operating system. Each distro will share many common features with other distros, such as the core kernel, user utilities, and other components. Where distros most often differ is their overall goal or purpose. For example, the following list describes several common distribution types:

• Commercial: A distro that is designed to be used in a business setting. Often these distros will be bundled together with a support contract. So, although the operating system itself may be free, the support contract will add a yearly fee. Commercial releases normally have a slower release cycle (3–5 years), resulting in a more stable and secure platform. Typical examples of commercial distros include Red Hat Enterprise Linux and SUSE.

• Home or amateur: These distros are focused on providing a Linux operating system to individuals who want a choice that isn’t either macOS or Microsoft Windows. Typically there is only community support for these distros, with very rapid release cycles (3–6 months), so all of the latest features are quickly available. Typical examples of amateur distros include Fedora, Linux Mint, and Ubuntu (although Ubuntu also has a release that is designed for commercial users).

• Security enhanced: Some distributions are designed around security. Either the distro itself has extra security features or it provides tools to enhance the security on other systems. Typical examples include Kali Linux and Alpine Linux.

• Live distros: Normally to use an operating system, you would first need to install it on a system. With a Live distribution, the system can boot directly from removable media, such as a CD-ROM, DVD, or USB disk. The advantage of Live distros is the ability to test out a distribution without having to make any changes to the contents of the system’s hard drive. Additionally, some Live distros come with tools to fix issues with the installed operating system (including Microsoft Windows issues). Typical examples of Live distros include Manjaro Linux and Antegros. Most modern amateur distros, such as Fedora and Linux Mint, also have a Live version.

Security Highlight

Commercial distributions tend to be more secure than distributions designed for home use. This is because commercial distributions are often used for system-critical tasks in corporations or the government, so the organizations that support these distributions often make security a key component of the operating system.

It is important to realize that these are only a few of the types of Linux distributions. There are also distros designed for educational purposes, young learners, beginners, gaming, older computers, and many others. An excellent source to learn more about available distributions is https://distrowatch.com. This site provides the ability to search for and download the software required to install many different distributions.

Shells

A shell is a software program that allows a user to issue commands to the system. If you have worked in Microsoft Windows, you may have used the shell environment provided for that operating system: DOS. Like DOS, the shells in Linux provide a command-line interface (CLI) to the user.

CLI commands provide some advantages. They tend to be more powerful and have more functions than commands in GUI applications. This is partly because creating CLI programs is easier than creating GUI programs, but also because some of the CLI programs were created even before GUI programs existed.

Linux has several different shells available. Which shells you have on your system will depend on what software has been installed. Each shell has specific features, functions, and syntax that differentiate it from other shells, but they all essentially perform the same functionality.

Although multiple different shells are available for Linux, by far the most popular shell is the BASH shell. The BASH shell was developed from an older shell named the Bourne Shell (BASH stands for Bourne Again SHell). Because it is so widely popular, it will be the primary focus of the discussions in this book.

GUI Software

When you install a Linux operating system, you can decide if you only want to log in and interact with the system via the CLI or if you want to install a GUI. GUI software allows you to use a mouse and keyboard to interact with the system, much like you may be used to within Microsoft Windows.

For personal use, on laptop and desktop systems, having a GUI is normally a good choice. The ease of using a GUI environment often outweighs the disadvantages that this software creates. In general, GUI software tends to be a big hog of system resources, taking up a higher percentage of CPU cycles and RAM. As a result, it is often not installed on servers, where these resources should be reserved for critical server functions.

Security Highlight

Consider that every time you add more software to the system, you add a potential security risk. Each software component must be properly secured, and this is especially important for any software that provides the means for a user to access a system.

GUI-based software is a good example of an additional potential security risk. Users can log in via a GUI login screen, presenting yet another means for a hacker to exploit the system. For this reason, system administrators tend to not install GUI software on critical servers.

As with shells, a lot of options are available for GUI software. Many distributions have a “default” GUI, but you can always choose to install a different one. A brief list of GUI software includes GNOME, KDE, XFCE, LXDE, Unity, MATE, and Cinnamon.

GUIs will not be a major component of this book. Therefore, we the authors suggest you try different GUIs and pick one that best meets your needs.

Installing Linux

Before installing Linux, you should answer the following questions:

• Which distribution will you choose? As previously mentioned, you have a large number of choices.

• What sort of installation should be performed? You have a couple of choices here because you can install Linux natively on a system or install the distro as a virtual machine (VM).

• If Linux is installed natively, is the hardware supported? In this case, you may want to shy away from newer hardware, particularly on newer laptops, as they may have components that are not yet supported by Linux.

• If Linux is installed as a VM, does the system have enough resources to support both a host OS and a virtual machine OS? Typically this comes does to a question of how much RAM the system has. In most cases, a system with at least 8GB of RAM should be able to support at least one VM.

Which Distro?

You might be asking yourself, “How hard can it be to pick a distribution? How many distros can there be?” The simple answer to the second question is “a lot.” At any given time, there are about 250 active Linux distributions. However, don’t let that number scare you off!

Although there are many distros, a large majority of them are quite esoteric, catering to very specific situations. While you are learning Linux, you shouldn’t concern yourself with these sorts of distributions.

Conversational Learning™ — Choosing a Linux Distribution

Gary: Hey, Julia.

Julia: You seem glum. What’s wrong, Gary?

Gary: I am trying to decided which Linux distro to install for our new server and I’m feeling very much overwhelmed.

Julia: Ah, I know the feeling, having been there many times before. OK, so let’s see if we can narrow it down. Do you feel you might need professional support for this system?

Gary: Probably not… well, not besides the help I get from you!

Julia: I sense more emails in my inbox soon. OK, that doesn’t narrow it down too much. If you had said “yes,” I would have suggested one of the commercial distros, like Red Hat Enterprise Linux or SUSE.

Gary: I’d like to pick one of the more popular distros because I feel they would have more community support.

Julia: That’s a good thought. According to distrowatch.com, there are several community-supported distros that have a lot of recent downloads, including Mint, Debian, Ubuntu, and Fedora.

Gary: I’ve heard of those, but there are others listed on distrowatch.com that I’ve never heard of before.

Julia: Sometimes those other distros may have some features that you might find useful. How soon do you need to install the new server?

Gary: Deadline is in two weeks.

Julia: OK, I recommend doing some more research on distrowatch.com, pick three to four candidates and install them on a virtual machine. Spend some time testing them out, including using the software that you will place on the server. Also spend some time looking at the community support pages and ask yourself if you feel they will be useful.

Gary: That sounds like a good place to start.

Julia: One more thing: consider that there isn’t just one possible solution. Several distros will likely fit your needs. Your goal is to eliminate the ones that won’t fit your needs first and then try to determine the best of the rest. Good luck!

A handful of distributions are very popular and make up the bulk of the Linux installations in the world. However, a complete discussion of the pros and cons of each of these popular distros is beyond the scope of this book. For the purpose of learning Linux, we the authors recommend you install one or more of the following distros:

• Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL), Fedora, or CentOS: These distributions are called Red Hat–based distros because they all share a common set of base code from Red Hat’s release of Linux. There are many others that share this code, but these are generally the most popular. Note that both Fedora and CentOS are completely free, while RHEL is a subscription-based distro. For Red Hat–based examples in this book, we will use Fedora.

• Linux Mint, Ubuntu, or Debian: These distributions are called Debian-based distros because they all share a common set of base code from Debian’s release of Linux. There are many others that share this code, but these are generally the most popular. For Debian-based examples in this book, we will use Ubuntu.

• Kali: This is a security-based distribution that will be used in several chapters of this book. Consider this distribution to be a tool that enables you to determine what security holes are present in your environment.

Native or Virtual Machine?

If you have an old computer available, you can certainly use it to install Linux natively (this is called a bare-metal or native installation). However, given the fact that you probably want to test several distributions, virtual machine (VM) installs are likely a better choice.

A VM is an operating system that thinks it is installed natively, but it is actually sharing a system with a host operating system. (There is actually a form of virtualization in which the VM is aware it is virtualized, but that is beyond the scope of this book and not necessary for learning Linux.) The host operating system can be Linux, but it could also be macOS or Microsoft Windows.

In order to create VMs, you need a product that provides a hypervisor. A hypervisor is software that presents “virtual hardware” to a VM. This includes a virtual hard drive, a virtual network interface, a virtual CPU, and other components typically found on a physical system. There are many different hypervisor software programs, including VMware, Microsoft Hyper-V, Citrix XenServer, and Oracle VirtualBox. You could also make use of hosted hypervisors, which are cloud-based applications. With these solutions, you don’t even have to install anything on your local system. Amazon Web Services is a good example of a cloud-based service that allows for hosted hypervisors.

Security Highlight

Much debate in the security industry revolves around whether virtual machines are more secure than bare-metal installations. There is no simple answer to this question because many aspects need to be considered. For example, although virtual machines may provide a level of abstraction, making it harder for a hacker to be aware of their existence, they also result in another software component that needs to be properly secured.

Typically, security isn’t the primary reason why an organization uses virtual machines (better hardware utilization is usually the main reason). However, if you choose to use virtual machines in your environment, the security impact should be carefully considered and included in your security policies.

For the purposes of learning Linux, we will use Oracle VirtualBox. It is freely available and works well on multiple platforms, including Microsoft Windows (which is most likely the operating system you already have installed on your own system). Oracle VirtualBox can be downloaded from https://www.virtualbox.org. The installation is fairly straightforward: just accept the default values or read the installation documentation (https://www.virtualbox.org/wiki/Downloads#manual).

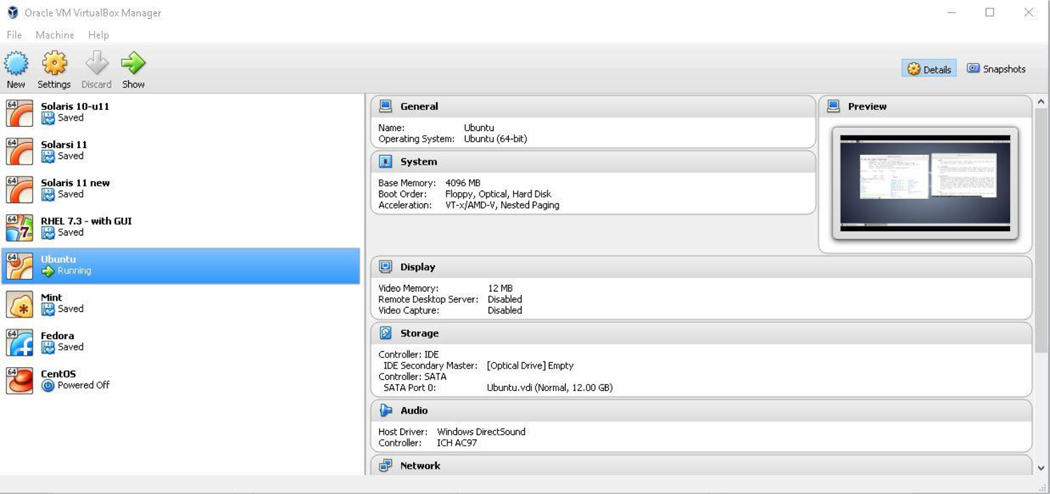

After you have installed Oracle VirtualBox and have installed some virtual machines, the Oracle VM VirtualBox Manager will look similar to Figure 1-2.

Figure 1-2 The Oracle VirtualBox VM Manager

Installing a Distro

If you are using Oracle VirtualBox, the first step to installing a distro is to add a new “machine.” This is accomplished by taking the following steps in the Oracle VM VirtualBox Manager:

1. Click Machine and then New.

2. Provide a name for the VM; for example, enter Fedora in the Name: box. Note that the Type and Version boxes will likely change automatically. Type should be Linux. Check the install media you downloaded to see if it is a 32-bit or 64-bit operating system (typically this info will be included in the filename). Most modern version are 64 bit.

3. Set the Memory Size value by using the sliding bar or typing the value in the MB box. Typically a value of 4196MB (about 4GB) of memory is needed for a full Linux installation to run smoothly.

Leave the option “Create a virtual hard disk now” marked.

4. Click the Create button.

5. On the next dialog box, you will choose the size of the virtual hard disk. The default value will likely be 8.00GB, which is a bit small for a full installation. A recommend minimum value is 12GB.

6. Leave the “Hard disk file type” set to VDI (Virtual Hard Disk). Change “Storage on physical hard disk” to Fixed Size.

7. Click the Create button.

After a short period of time (a few minutes), you should see your new machine in the list on the left side of the Oracle VM VirtualBox Manager. Before continuing to the next step, make sure you know the location of your installation media (the *.iso file of the Linux distro you downloaded).

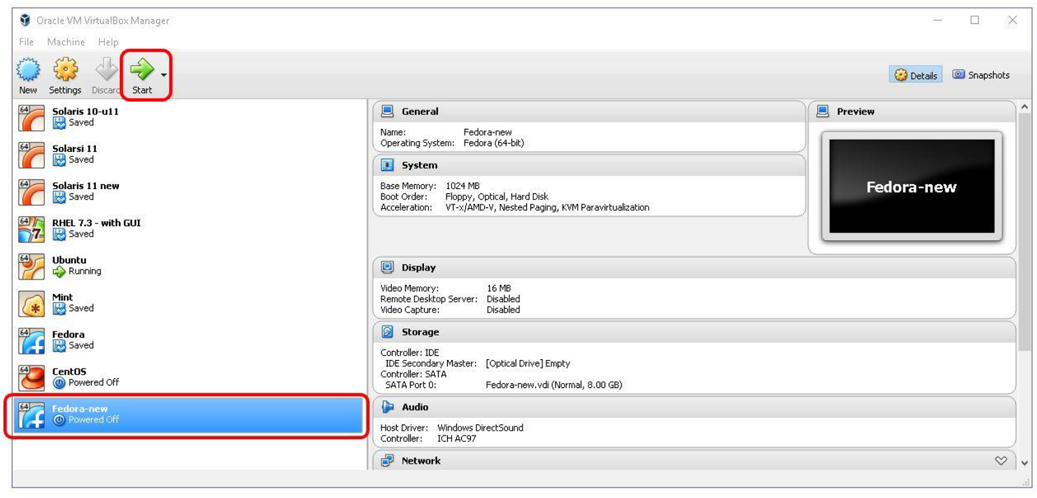

To start the installation process, click the new machine and then click the Start button. See Figure 1-3 for an example.

Figure 1-3 Start the Installation Process

In the next window that appears, you need to select the installation media. In the Select Start-up Disk dialog box, click the small icon that looks like a folder with a green “up arrow.” Then navigate to the folder that contains the installation media, select it, and click the Open button. When you return to the dialog box, click the Start button.

Once the installation starts, the options and prompts really depend on which distribution you are installing. These can also change as newer versions of the distributions are released. As a result of how flexible these installation processes can be, we recommend you follow the installation guides provided by the organization that released the distribution.

Instead of providing specific instructions, we offer the following recommendations:

• Accept the defaults. Typically the default options work well for your initial installations. Keep in mind that you can always reinstall the operating system later.

• Don’t worry about specific software. One option may require that you select which software to install. Again, select the default provided. You can always add more software later, and you will learn how to do this in Chapter 25, “System Logging,” and Chapter 26, “Red Hat-Based Software Management.”

• Don’t forget that password. You will be asked to set a password for either the root account or a regular user account. On a production system, you should make sure you set a password that isn’t easy to compromise. However, on these test systems, pick a password that is easy to remember, as password security isn’t as big of a concern in this particular case. If you do forget your password, recovering passwords is covered in Chapter 28, “System booting,” (or you can reinstall the Linux OS).

Summary

After reading this chapter, you should have a better understanding of the major components of the Linux operating system. You should also know what a Linux distribution is and have an idea of the questions you should answer prior to installing Linux.

Key Terms

Review Questions

1. A _____ is a structure that is used to organize files and directories in an operating system.

2. Which of the following is not a common component of a Linux operating system?

a. kernel

b. libraries

c. disk drive

d. shells

3. Which of the following is a security-based Linux distribution?

a. Fedora

b. CentOS

c. Debian

d. Kali

4. A _____ program provides a command-line interface to the Linux operating system.

5. A _____ is an operating system that thinks it is installed natively, but it is actually sharing a system with a host operating system.