You can use the set commands to help with debugging your scripts. There are two common options to set, x and v. Here is a description of each.

Note that a - activates the set while a + deactivates it. If that sounds backwards to you it is because it is backwards.

Use:

set -x: to display the expanded trace before running the commandset -v: to display the input line as it is parsed

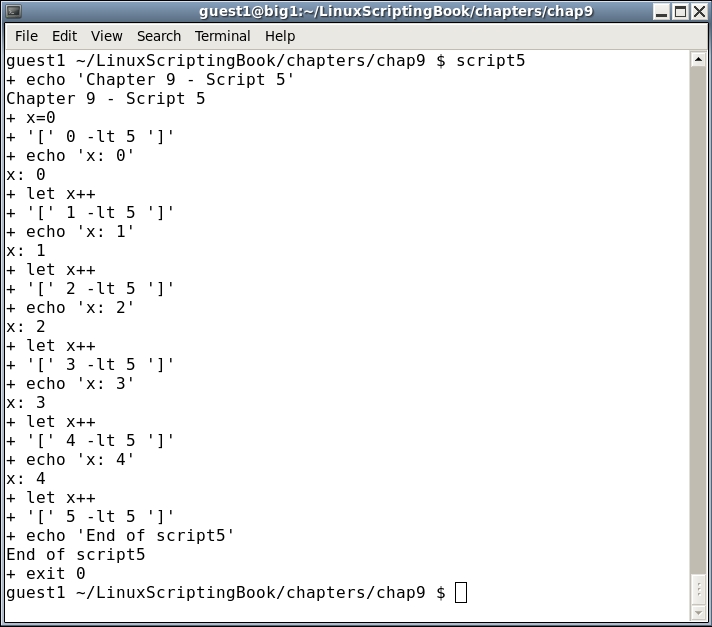

Take a look at Script 5 which shows what set -x does:

#!/bin/sh # # 6/7/2017 # set -x # turn debugging on echo "Chapter 9 - Script 5" x=0 while [ $x -lt 5 ] do echo "x: $x" let x++ done echo "End of script5" exit 0

And the output:

If this looks a little strange at first don't worry, it gets easier the more you look at it. In essence, the lines that start with a + are the expanded source code lines, and the lines without a + are the output of the script.

Look at the first two lines. It shows:

+ echo 'Chapter 9 - Script 5' Chapter 9 - Script 5

The first line shows the expanded command and the second the output.

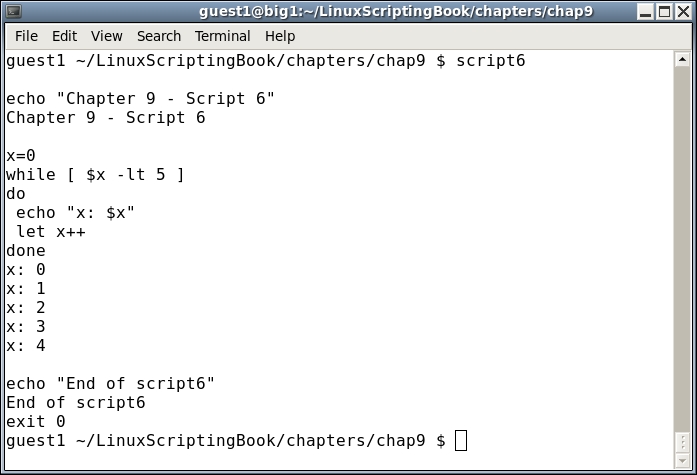

You can also use the set -v option. Here is a screenshot of Script 6 which is just Script 5 but with set -v this time:

You can see the output is quite a bit different.

Note that with the set commands you can turn them on and off at any point you want in the script. This is so you can limit the output to just the areas of the code you are interested in.

Let's look at an example of this:

#!/bin/sh

#

# 6/8/2017

#

set +x # turn debugging off

echo "Chapter 9 - Script 7"

x=0

for fn in *.txt

do

echo "x: $x - fn: $fn"

array[$x]="$fn"

let x++

done

maxx=$x

echo "Number of files: $maxx"

set -x # turn debugging on

x=0

while [ $x -lt $maxx ]

do

echo "File: ${array[$x]}"

let x++

done

set +x # turn debugging off

echo "End of script7"

exit 0

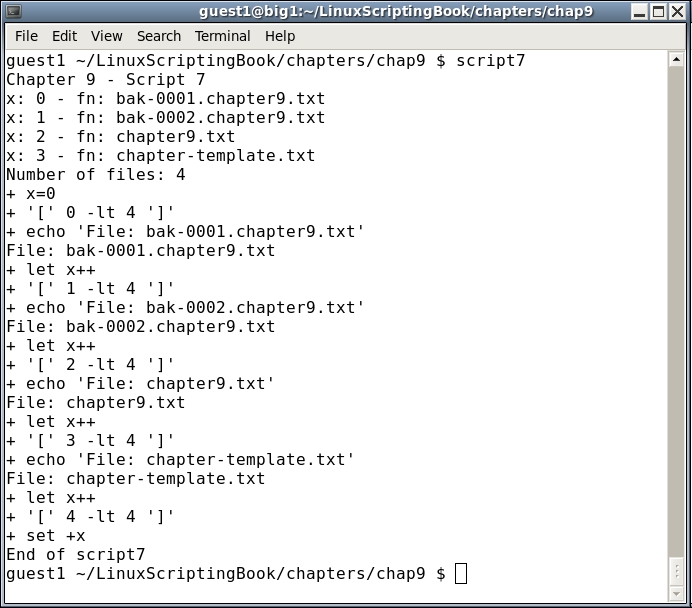

Notice how the debugging was explicitly turned off at the beginning of the script even though it is off by default. This is a good way to keep track of when it is off and when it is on. Look at the output closely and see how the debug statements don't start displaying until the second loop with the array. Then it is turned off before running the last two lines.

The output when using the set commands can be pretty hard to look at sometimes and so this is a good way to limit what you have to wade through to get to the lines of interest.

There is another debugging technique that I use quite frequently. In many cases I think it is superior to using the set commands as the display does not get quite as cluttered. You may recall in Chapter 6, Automating Tasks with Scripts, that we were able to display output to other terminals. This is a very handy feature.

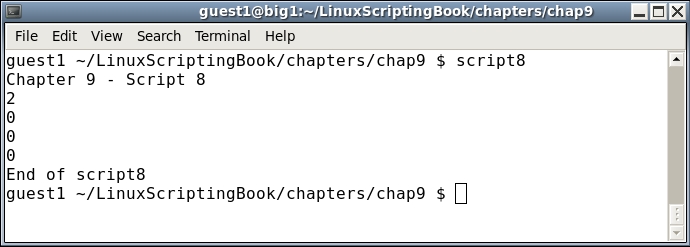

The following script shows how to display output in another terminal. A subroutine is used for convenience:

#!/bin/sh

#

# 6/8/2017

#

echo "Chapter 9 - Script 8"

TTY=/dev/pts/35 # TTY of other terminal

# Subroutines

p1() # display to TTY

{

rc1=0 # default is no error

if [ $# -ne 1 ] ; then

rc1=2 # missing parameter

else

echo "$1" > $TTY

rc1=$? # set error status of echo command

fi

return $rc1

}

# Code

p1 # missing parameter

echo $?

p1 Hello

echo $?

p1 "Linux Rules!"

echo $?

p1 "Programming is fun!"

echo $?

echo "End of script8"

exit 0

Remember to quote the parameter to p1 in case it contains blank characters.

This subroutine might be a bit of overkill to use for debugging but it captures many of the concepts previously discussed in this book. This approach can also be used in a script to display information in multiple terminals. We will go over that in the next chapter.

It probably means the terminal has not been opened yet. Also remember to put your terminal device strings into a variable because those tend to change after a reboot. Something like TTY=/dev/pts/35 is a good idea.

A great time to use this debugging technique is when writing a form script as we did in Chapter 5, Creating Interactive Scripts. So, let's take a look at that script again and put this new subroutine to use.

#!/bin/sh

# 6/8/2017

# Chapter 9 - Script 9

#

TTY=/dev/pts/35 # debug terminal

# Subroutines

cls()

{

tput clear

}

move() # move cursor to row, col

{

tput cup $1 $2

}

movestr() # move cursor to row, col

{

tput cup $1 $2

echo -n "$3" # display string

}

checktermsize()

{

p1 "Entering routine checktermsize."

rc1=0 # default is no error

if [[ $LINES -lt $1 || $COLUMNS -lt $2 ]] ; then

rc1=1 # set return code

fi

return $rc1

}

init() # set up the cursor position array

{

p1 "Entering routine init."

srow[0]=2; scol[0]=7 # name

srow[1]=4; scol[1]=12 # address 1

srow[2]=6; scol[2]=12 # address 2

srow[3]=8; scol[3]=7 # city

srow[4]=8; scol[4]=37 # state

srow[5]=8; scol[5]=52 # zip code

srow[6]=10; scol[6]=8 # email

}

drawscreen() # main screen draw routine

{

p1 "Entering routine drawscreen."

cls # clear the screen

movestr 0 25 "Chapter 9 - Script 9"

movestr 2 1 "Name:"

movestr 4 1 "Address 1:"

movestr 6 1 "Address 2:"

movestr 8 1 "City:"

movestr 8 30 "State:"

movestr 8 42 "Zip code:"

movestr 10 1 "Email:"

}

getdata()

{

p1 "Entering routine getdata."

x=0 # array subscript

rc1=0 # loop control variable

while [ $rc1 -eq 0 ]

do

row=${srow[x]}; col=${scol[x]}

p1 "row: $row col: $col"

move $row $col

read array[x]

let x++

if [ $x -eq $sizeofarray ] ; then

rc1=1

fi

done

return 0

}

showdata()

{

p1 "Entering routine showdata."

fn=0

echo ""

read -p "Enter filename, or just Enter to skip: " filename

if [ -n "$filename" ] ; then # if not blank

echo "Writing to '$filename'"

fn=1 # a filename was given

fi

echo "" # skip 1 line

echo "Data array contents: "

y=0

while [ $y -lt $sizeofarray ]

do

echo "$y - ${array[$y]}"

if [ $fn -eq 1 ] ; then

echo "$y - ${array[$y]}" >> "$filename"

fi

let y++

done

return 0

}

p1() # display to TTY

{

rc1=0 # default is no error

if [ $# -ne 1 ] ; then

rc1=2 # missing parameter

else

echo "$1" > $TTY

rc1=$? # set error status of echo command

fi

return $rc1

}

# Code starts here

p1 " " # carriage return

p1 "Starting debug of script9"

sizeofarray=7 # number of array elements

if [ "$1" = "--help" ] ; then

p1 "In Usage clause."

echo "Usage: script9 --help"

echo " This script shows how to create an interactive screen program"

echo " and how to use another terminal for debugging."

exit 255

fi

checktermsize 25 80

rc=$?

if [ $rc -ne 0 ] ; then

echo "Please size the terminal to 25x80 and try again."

exit 1

fi

init # initialize the screen array

drawscreen # draw the screen

getdata # cursor movement and data input routine

showdata # display the data

p1 "At exit."

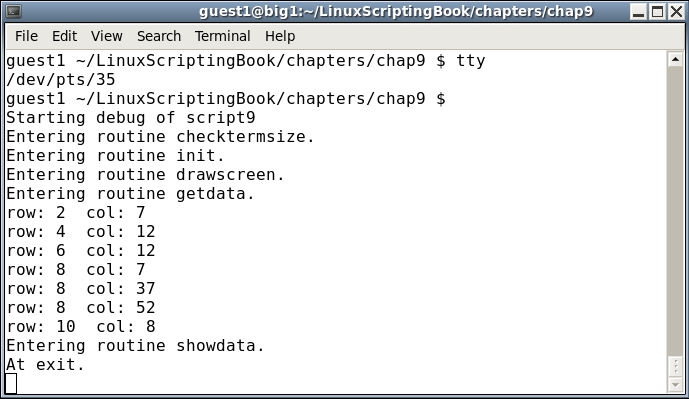

exit 0Here is the output from the debug terminal (dev/pts/35):

By having the debug information display in another terminal it is much easier to see what is happening in the code.

You can put the p1 routine where ever you think the problem might be. Labeling which subroutine is being used can also help locate if the problem is in a subroutine or in the main code body.

When your script is completed and ready for use, you don't have to remove the calls to the p1 routine unless you really want to. You can just code a return 0 at the top of the routine.

I use this approach when debugging shell scripts or C programs and it has always worked very well for me.