This chapter shows how to read the keyboard in order to create interactive scripts.

The topics covered in this chapter are:

- How to use the

readbuilt-in command to query the keyboard. - The different ways to use

read. - The use of traps (interrupts).

The reader will learn how to create interactive scripts.

The scripts we have looked at up to this point have run without much user interaction. The read command is used to create scripts that can query the keyboard. The code can then take action based on the input.

#!/bin/sh # # 5/16/2017 # echo "script1 - Linux Scripting Book" echo "Enter 'q' to quit." rc=0 while [ $rc -eq 0 ] do echo -n "Enter a string: " read str echo "str: $str" if [ "$str" = "q" ] ; then rc=1 fi done echo "End of script1" exit 0

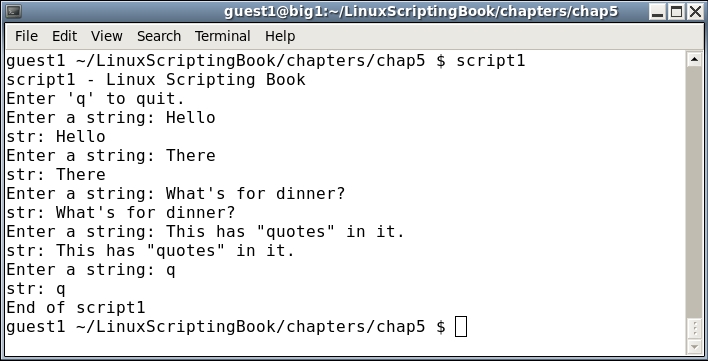

And here is the output when run on my system:

This is a good one to run on your system. Try several different strings, numbers, and so on. Notice how the returned string contains whitespace, special characters, and so on. You don't have to quote anything, and if you do those will be returned as well.

You can also use the read command to put a simple pause into your script. This will allow you to see the output before it scrolls off the screen. It can also be used when debugging which will be shown in Chapter 9, Debugging Scripts.

The following script shows how to create a pause when the output gets to the last line of the screen:

#!/bin/sh # # 5/16/2017 # Chapter 5 - Script 2 # linecnt=1 # line counter loop=0 # loop control var while [ $loop -eq 0 ] do echo "$linecnt $RANDOM" # display next random number let linecnt++ if [ $linecnt -eq $LINES ] ; then linecnt=1 echo -n "Press Enter to continue or q to quit: " read str # pause if [ "$str" = "q" ] ; then loop=1 # end the loop fi fi done echo "End of script2" exit 0

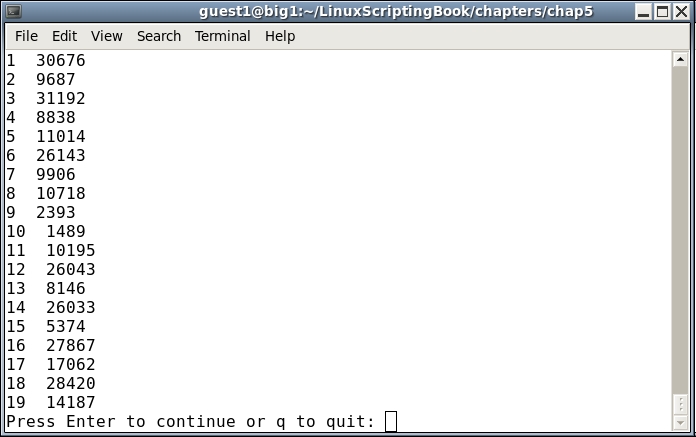

And here is the output when run on my system:

I pressed Enter twice, and then Q and Enter on the last one.

Let's try something a bit more interesting. This next script shows how to fill an array with values taken from the keyboard:

#!/bin/sh

#

# 5/16/2017

#

echo "script3 - Linux Scripting Book"

if [ "$1" = "--help" ] ; then

echo "Usage: script3"

echo " Queries the user for values and puts them into an array."

echo " Entering 'q' will halt the script."

echo " Running 'script3 --help' shows this Usage message."

exit 255

fi

x=0 # subscript into array

loop=0 # loop control variable

while [ $loop -eq 0 ]

do

echo -n "Enter a value or q to quit: "

read value

if [ "$value" = "q" ] ; then

loop=1

else

array[$x]="$value"

let x++

fi

done

let size=x

x=0

while [ $x -lt $size ]

do

echo "array $x: ${array[x]}"

let x++

done

echo "End of script3"

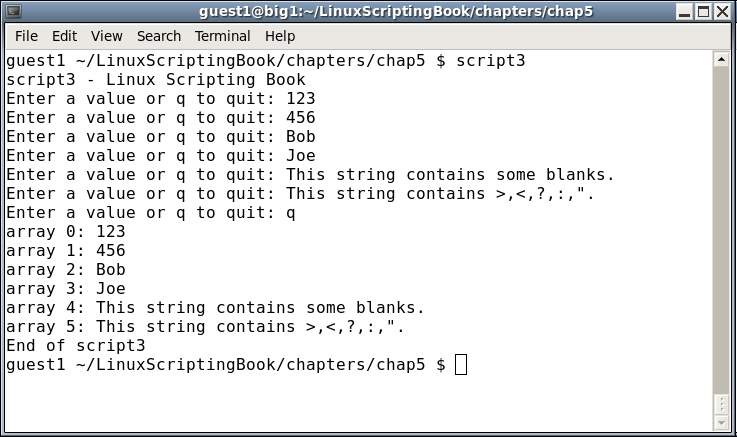

exit 0And the output:

Since this script does not require any parameters I decided to add a Usage statement. This will display if the user runs it with --help and is a common feature in many system scripts and programs.

The only thing new in this script is the read command. The loop and array variables were discussed in an earlier chapter. Note again that, with the read command what you type is what you get.

Now let's create a complete interactive script. But first we need to check the size of the current terminal. If it is too small, the output of your script may become garbled and the user may not know why or how to fix it.

The following script contains a subroutine that checks the size of the terminal:

#!/bin/sh

#

# 5/16/2017

#

echo "script4 - Linux Scripting Book"

checktermsize()

{

rc1=0 # default is no error

if [[ $LINES -lt $1 || $COLUMNS -lt $2 ]] ; then

rc1=1 # set return code

fi

return $rc1

}

rc=0 # default is no error

checktermsize 40 90 # check terminal size

rc=$?

if [ $rc -ne 0 ] ; then

echo "Return code: $rc from checktermsize"

fi

exit $rcRun this on your system with different-sized terminals to check the result. As you can see from the code, it's okay if the terminal is larger than needed; it just can't be too small.

Now let's look at a full interactive script:

#!/bin/sh

#

# 5/27/2017

#

echo "script5 - Linux Scripting Book"

# Subroutines

cls()

{

tput clear

}

move() # move cursor to row, col

{

tput cup $1 $2

}

movestr() # move cursor to row, col

{

tput cup $1 $2

echo -n "$3" # display string

}

checktermsize()

{

rc1=0 # default is no error

if [[ $LINES -lt $1 || $COLUMNS -lt $2 ]] ; then

rc1=1 # set return code

fi

return $rc1

}

init() # set up the cursor position array

{

srow[0]=2; scol[0]=7 # name

srow[1]=4; scol[1]=12 # address 1

srow[2]=6; scol[2]=12 # address 2

srow[3]=8; scol[3]=7 # city

srow[4]=8; scol[4]=37 # state

srow[5]=8; scol[5]=52 # zip code

srow[6]=10; scol[6]=8 # email

}

drawscreen() # main screen draw routine

{

cls # clear the screen

movestr 0 25 "Chapter 5 - Script 5"

movestr 2 1 "Name:"

movestr 4 1 "Address 1:"

movestr 6 1 "Address 2:"

movestr 8 1 "City:"

movestr 8 30 "State:"

movestr 8 42 "Zip code:"

movestr 10 1 "Email:"

}

getdata()

{

x=0 # array subscript

rc1=0 # loop control variable

while [ $rc1 -eq 0 ]

do

row=${srow[x]}; col=${scol[x]}

move $row $col

read array[x]

let x++

if [ $x -eq $sizeofarray ] ; then

rc1=1

fi

done

return 0

}

showdata()

{

fn=0

echo ""

read -p "Enter filename, or just Enter to skip: " filename

if [ -n "$filename" ] ; then # if not blank

echo "Writing to '$filename'"

fn=1 # a filename was given

fi

echo "" # skip 1 line

echo "Data array contents: "

y=0

while [ $y -lt $sizeofarray ]

do

echo "$y - ${array[$y]}"

if [ $fn -eq 1 ] ; then

echo "$y - ${array[$y]}">>"$filename"

fi

let y++

done

return 0

}

# Code starts here

sizeofarray=7 # number of array elements

if [ "$1" = "--help" ] ; then

echo "Usage: script5 --help"

echo " This script shows how to create an interactive screen program."

exit 255

fi

checktermsize 25 80

rc=$?

if [ $rc -ne 0 ] ; then

echo "Please size the terminal to 25x80 and try again."

exit 1

fi

init # initialize the screen array

drawscreen # draw the screen

getdata # cursor movement and data input routine

showdata # display the data

exit 0

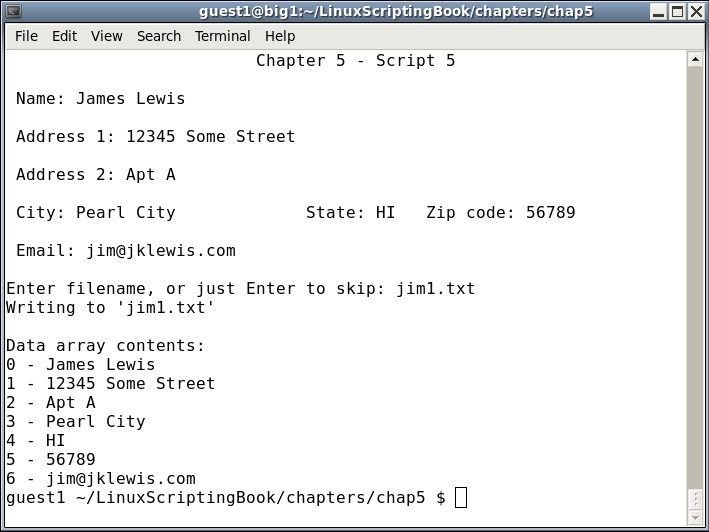

There is a lot of new information here, so let's take a look. First the subroutines are defined, and you can see we included the checktermsize subroutine from the preceding Script 4.

The init routine sets up the cursor placement array. It's good programming practice to put initial values in a subroutine, particularly if it is going to be called again.

The drawscreen routine displays the initial form. Note that I could have used the values in the srow and scol array here, however, I didn't want the script to look too cluttered.

Look very carefully at the getdata routine because this is where the fun begins:

- First the array subscript

xand control varrc1are set to0. - In the loop the cursor is placed at the first position (

Name:). - The keyboard is queried and the user's input goes into the array at sub

x. xis incremented and we go to the next field.- If

xis equal to the size of the array we leave the loop. Keep in mind that we start counting at0.

The showdata routine displays the array data and then we are done.

This is just a small example of an interactive script to show the basic concepts. In a later chapter we will go into this in more detail.

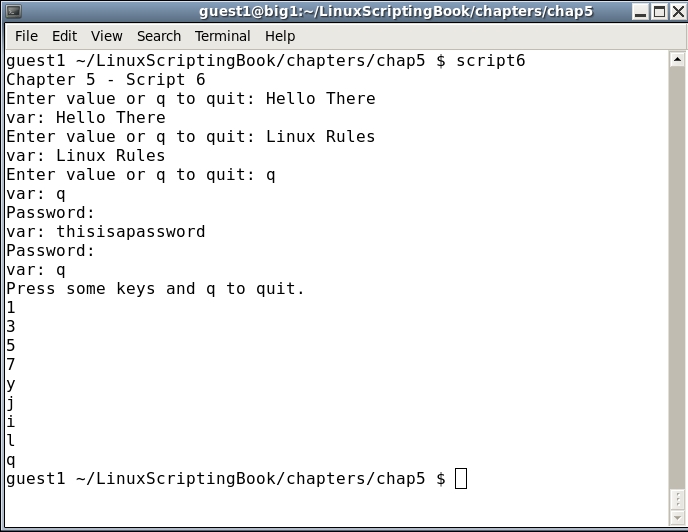

The read command can be used in a number of different ways. Here are a few examples:

read var Wait for input of characters into the variable var. read -p "string" var Display contents of string, stay on the line, and wait for input. read -p "Enter password:" -s var Display "Enter password:", but do not echo the typing of the input. Note that a carriage return is not output after Enter is pressed. read -n 1 var

The -n option means to wait for that number of characters and then continue, it does not wait for an Enter press.

In this example it will wait for 1 char and then go. This can be useful in utility scripts and games:

#!/bin/sh # # 5/27/2017 # echo "Chapter 5 - Script 6" rc=0 # return code while [ $rc -eq 0 ] do read -p "Enter value or q to quit: " var echo "var: $var" if [ "$var" = "q" ] ; then rc=1 fi done rc=0 # return code while [ $rc -eq 0 ] do read -p "Password: " -s var echo "" # carriage return echo "var: $var" if [ "$var" = "q" ] ; then rc=1 fi done echo "Press some keys and q to quit." rc=0 # return code while [ $rc -eq 0 ] do read -n 1 -s var # wait for 1 char, does not output it echo $var # output it here if [ "$var" = "q" ] ; then rc=1 fi done exit $rc

The comments in the script should make this one pretty self explanatory. The read command has a few more options, one of which will be shown in the next script.

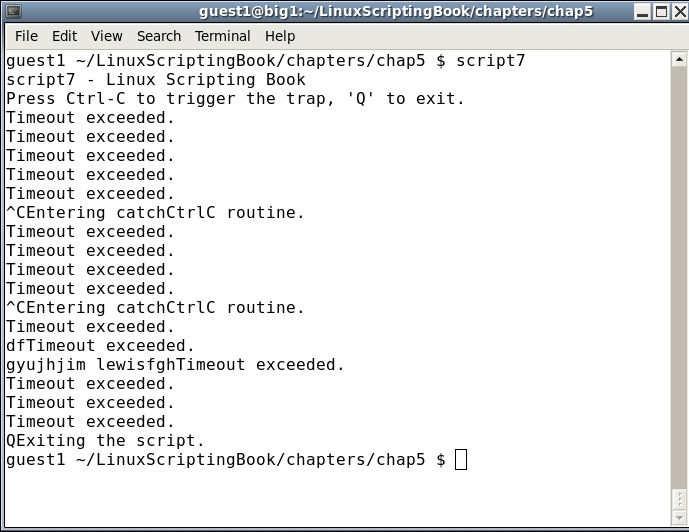

Another way to query the keyboard is by using what is called a trap. This is a subroutine that is accessed when a special key sequence is pressed, such as Ctrl + C.

Here is an example of using a trap:

#!/bin/sh

#

# 5/16/2017

#

echo "script7 - Linux Scripting Book"

trap catchCtrlC INT # Initialize the trap

# Subroutines

catchCtrlC()

{

echo "Entering catchCtrlC routine."

}

# Code starts here

echo "Press Ctrl-C to trigger the trap, 'Q' to exit."

loop=0

while [ $loop -eq 0 ]

do

read -t 1 -n 1 str # wait 1 sec for input or for 1 char

rc=$?

if [ $rc -gt 128 ] ; then

echo "Timeout exceeded."

fi

if [ "$str" = "Q" ] ; then

echo "Exiting the script."

loop=1

fi

done

exit 0Here is the output on my system:

Try running this one on your system. Press some keys and see the response. Press Ctrl + C a few times as well. When done press Q.

That read statement needs some further explanation. Using read with the -t option (timeout) means to wait that many seconds for a character. If one is not input in the allotted time it will return a code with a value greater than 128. As we have seen before, the -n 1 option tells read to wait for 1 character. So this means we are waiting 1 second for 1 character. This is another way read can be used to create a game or other interactive script.

If you get yourself into a situation where you can't exit a script you can use the kill command.

For example, if I had needed to stop script7 the directions would be follows:

guest1 $ ps auxw | grep script7 guest1 17813 0.0 0.0 106112 1252 pts/32 S+ 17:23 0:00 /bin/sh ./script7 guest1 17900 0.0 0.0 103316 864 pts/18 S+ 17:23 0:00 grep script7 guest1 29880 0.0 0.0 10752 1148 pts/17 S+ 16:47 0:00 kw script7 guest1 $ kill -9 17813 guest1 $

In the terminal where script7 was running you will see it has stopped with the word Killed in it.

Note, be sure to kill the right process!

In the example above, PID 29880 is my text editor session where I am writing script7. Killing that would not be a good idea :).

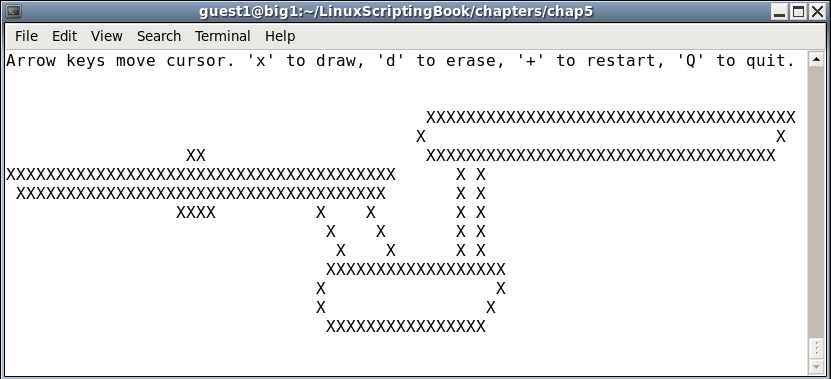

Now for some fun! The next script allows you to draw crude pictures on the screen:

#!/bin/sh

#

# 5/16/2017

#

echo "script8 - Linux Scripting Book"

# Subroutines

cls()

{

tput clear

}

move() # move cursor to row, col

{

tput cup $1 $2

}

movestr() # move cursor to row, col

{

tput cup $1 $2

echo -n "$3" # display string

}

init() # set initial values

{

minrow=1 # terminal boundaries

maxrow=24

mincol=0

maxcol=79

startrow=1

startcol=0

}

restart() # clears screen, sets initial cursor position

{

cls

movestr 0 0 "Arrow keys move cursor. 'x' to draw, 'd' to erase, '+' to restart, 'Q' to quit."

row=$startrow

col=$startcol

draw=0 # default is not drawing

drawchar=""

}

checktermsize2() # must be the specified size

{

rc1=0 # default is no error

if [[ $LINES -ne $1 || $COLUMNS -ne $2 ]] ; then

rc1=1 # set return code

fi

return $rc1

}

# Code starts here

if [ "$1" = "--help" ] ; then

echo "Usage: script7 --help"

echo " This script shows the basics on how to create a game."

echo " Use the arrow keys to move the cursor."

echo " Press c to restart and Q to quit."

exit 255

fi

checktermsize2 25 80 # terminal must be this size

rc=$?

if [ $rc -ne 0 ] ; then

echo "Please size the terminal to 25x80 and try again."

exit 1

fi

init # initialize values

restart # set starting cursor pos and clear screen

loop=1

while [ $loop -eq 1 ]

do

move $row $col # position the cursor here

read -n 1 -s ch

case "$ch" in

A) if [ $row -gt $minrow ] ; then

let row--

fi

;;

B) if [ $row -lt $maxrow ] ; then

let row++

fi

;;

C) if [ $col -lt $maxcol ] ; then

let col++

fi

;;

D) if [ $col -gt $mincol ] ; then

let col--

fi

;;

d) echo -n "" # delete char

;;

x) if [ $col -lt $maxcol ] ; then

echo -n "X" # put char

let col++

fi

;;

+) restart ;;

Q) loop=0 ;;

esac

done

movestr 24 0 "Script completed normally."

echo "" # carriage return

exit 0This was fun to write and a bit more fun to play with than I expected it to be.

One thing we haven't covered yet is the case statement. This is similar to an if...then...else but makes the code easier to read. Basically, the value that was input to the read statement is checked for a match in each case clause. If it matches, that stanza is executed and then control goes to the line after the esac statement. It also does this if there is no match.

Try this script, and remember to make the terminal 25x80 (or 80x25 if that is how your GUI works).

Here is just one example of what can be done with this script:

Well okay I guess this shows that I am not much of an artist. I will stick to programming and writing books.