Technical Trends

Digital forensics is a new field; however, people have been analyzing digital systems and associated components since the first computers began to be used in business. At that time, early forensic investigators used tools to store and process data and support decision making. The use of digital systems grew and evolved; so did the need to analyze those systems. Investigators needed to be able to determine what had been done and who was responsible.

One of the earliest uses of digital systems was to compute payroll. One of the earliest digital crimes was taking the “round-off”—the half-cent variance resulting from calculating an individual’s pay. A criminal would move that round-off to his or her own account. In this type of fraud, a perpetrator stole very small amounts each time. However, the number of paychecks calculated made the total fraud quite large. This showed that digital crime is relatively easy to commit and difficult to detect. To make the situation worse, the courts frequently sentenced perpetrators to probation instead of prison.

Digital technology provides many benefits and reduces costs in a number of ways. Therefore, the use of digital technology to support business processes and nearly every other facet of modern life has increased. In parallel, criminals have made increasingly innovative use of digital techniques in their activities. The methods of protecting digital systems and associated assets have also grown. However, they haven’t grown fast enough to keep pace with the growing number and complexity of attacks. Attackers now realize that there are many ways to obtain benefits from digital systems illegally. They can steal money and identities, and they can commit blackmail.

In a 1965 paper, Gordon E. Moore, cofounder of Intel, noted that the number of components in integrated circuits had doubled every 18 to 24 months from the invention of the integrated circuit in 1958 until 1965. He predicted that the trend would continue for at least 10 more years. In other words, he predicted, the number of transistors on an integrated circuit would double every 2 years for the next 10 years. This statement regarding the progression of integrated circuit capacity and capability became widely known as Moore’s law, sometimes also called Moore’s observation. More important, though, each doubling of capacity was done at half the cost. This means that a component that cost $100 would have twice the capability but would cost only $50 within 18 to 24 months. This can be seen in hundreds of modern digital devices, from DVD players and cell phones to computers and medical equipment.

Moore’s law achieved its name and fame because it proved to be an accurate representation of a trend that continues today. Specifically, the capacity and capability of integrated circuits have doubled and the cost has been halved every 18 to 24 months since Moore noted the trend. Further, Moore’s law applies to more than just integrated circuits. It also applies to some of the other primary drivers of computing capability: storage capacity; processor speed, capacity, and cost; fiber optic communications; and more.

Only human ingenuity limits new uses for technological solutions. In the 1950s, the UNIVAC I, the first commercial digital computer, was touted as having the capability to meet an organization’s total computing requirements. Today, a typical low-end mobile phone has more capability and capacity than the UNIVAC I.

Moore’s law also applies to digital forensics. You can expect to conduct investigations requiring analysis of an increasing volume of data from an increasing number of digital devices. Unfortunately, in the forensic world, Moore’s law operates as if it’s on steroids.

For example, digital storage capacity for a particular device might double in a year. The data that you might need to analyze could easily experience double that growth level. For example, a standard point-and-shoot digital camera now takes 5-megapixel photos. Highend cameras take 16-megapixel—or larger—photos. A typical Windows XP build consumes roughly 4 GB of disk space. A typical Windows 8 or Windows 10 build consumes 8 GB to 10 GB. Although a single copy of a file or data record might be maintained for active use, you must often locate and examine all prior copies of that file.

Because of Moore’s law, forensic specialists must develop new techniques, new software, and new hardware to perform forensic assessments. New techniques should simplify documentation of the chain of custody. You will have to determine what techniques have the greatest potential for obtaining needed information. In most investigations, analyzing all available data would be so costly as to be infeasible. Therefore, selectively evaluate data. Such selectivity is not unique to the digital world. It is the same concept that investigators have used for years to follow leads. For example, they often start by interviewing the most likely suspects and follow where the data leads to reach a conclusion. However, the U.S. legal system, helped by advertising and popular television, expects digital forensics to be unconstrained by such mundane factors as time, money, and available technology.

What Impact Does This Have on Forensics?

How does increasing computing power affect forensic investigations? The most obvious impact is the need for more storage on forensic servers. Most forensic labs use servers to store forensic images of suspect machines. If average laptops have 400 gigabytes (GB) to over a terabyte (TB) in hard drive storage, the server must be able to accommodate many terabytes of data.

The process of imaging a disk can also be slower. For example, utilizing the forensic dd utility with the netcat utility to image a suspect machine requires transmitting the image over a network. Clearly, the larger the drive being imaged, the more bandwidth will be required. It is recommended that forensic labs use the highest-capacity cabling available for the forensic lab, even possibly optical cable. To do otherwise will affect the efficiency of future forensic investigations.

Software as a Service

When computing first entered the marketplace, computer manufacturers typically provided software as part of a bundled product. A bundled product includes hardware, software, maintenance, and support sold together for a single price. It wasn’t long before the industry recognized that it could sell software products individually. This resulted in the rise of companies such as Microsoft.

Another approach to selling software arose. This approach involves selling access to needed software on a time-sharing basis. The price of the software was essentially embedded in a mathematical algorithm, and a user paid for software based on his or her usage profile. This pricing model continued into personal computer (PC) and server technology.

Then the pricing algorithm was changed to address a number of concurrent users, a number of instances, or some other model. In addition, the idea of buying use of a software product morphed into the concept of software as a service (SaaS)—that is, software that a provider licenses to customers as a service on demand, through a subscription model.

The model under which an organization obtains software is important to forensic analysis because it affects four areas of an investigation:

Who owns the software? Know whom to contact to obtain information regarding the functionality and patch levels of software.

How can you get access to the program code? When software is obtained as a shared service, access is usually not possible. In such cases, use alternative techniques.

What assurance do you have of the safety of a software product? You need to know that a particular software product doesn’t contain malware that could alter the investigation.

How can you keep the status of shared software static until the forensic investigation is complete?

The Cloud

It seems in any conversation about computer networks today you will hear mention of “the cloud.” What exactly is it, and how does it affect forensics? These are important questions now and will become more so in the next few years.

What is the cloud? In many ways, it is the concept of connectivity or a simplified way of thinking about the network. If you think about the Internet, for instance, it is actually a complex mesh of routers and paths. However, if it is drawn simply as a cloud, it is possible to concentrate on what can be done with the Internet, not how the Internet does what it does. For example, the idea of getting an email from one point to the other through the cloud is a very simple one to understand without knowing the intricate details about how it is accomplished.

A Cloud Is Born

It may be urban legend, but the origin of the cloud is often traced to an IBM salesman, his customer, and a chalk-board in late 1973 or early 1974. Upon returning from an internal training class on the then-new IBM Systems Network Architecture (SNA), the technically astute salesman attempted to explain mainframes, 3270 terminals, front-end processors, and a myriad of SNA logical unit and physical unit designations and definitions. He drew this new IBM world on a chalkboard as he spoke. As the salesman talked, the customer became wearier, and his eyes glazed over at all of the new jargon and complexity. The customer finally asked if it was necessary to understand all of the complexity before placing an order. Of course not, explained the IBM salesman. He quickly erased what was on the chalkboard between the mainframe computer and the end user terminal, and what was left looked like a cloud connecting the two. From that time forward, the complexity of the network and all of its connections has been known as “the cloud,” which is a simplified way of envisioning the connectivity. The cloud has existed for a long time, but the big deal is that because the cloud is being used for more than basic connectivity—that is, networking—the cloud now houses valuable services.

From the standpoint of a forensic examiner, though, the cloud is being used increasingly to create a physical distance between important elements. As an example, storage as a service allows a computer in one place to connect to actual storage embedded in the cloud. Not only is it usually less expensive, but there are a number of other benefits. The information is automatically backed up and is available in many locations and even on different computers, potentially to other users. It is clear that the increased ease of access in additional locations and potentially to additional people changes the forensic outlook on computer storage and potentially adds a number of additional considerations, such as tampering, chain of custody, and even the evidentiary value of the information.

One way that the cloud is implemented is network redundancy taken to a new level. In order to address disaster recovery, it is imperative for a robust network to have multiple redundant servers. In this way, if one fails, the organization simply uses the other server, often called the mirror server. In the simplest configuration, there are two servers that are connected. They are complete mirrors of each other. Should one server fail for any reason, all traffic is diverted to the other server.

This situation works great in environments where there are only a few servers and the primary concern is hardware failure. But what if you have much larger needs—for example, the need to store far more data than any single server can accommodate? Well, that led to the next step in the evolution of network redundancy, the storage area network (SAN). In a SAN, multiple servers and storage devices are all connected in a small high-speed network. This network is separate from the main network used by the organization. When a user on the main network wants to access data from the SAN, it appears to the user as a single logical storage device, though it may actually be composed of several physical storage devices. The user need not even be aware a SAN exists—from his or her perspective, it is just a server. This not only provides increased storage capacity, but also provides high availability and fault tolerance. The SAN has multiple servers; should one of them fail, the others will continue operating and the end user will not even realize a failure occurred.

There are two problems with the solutions mentioned so far. The first is capacity. Even a SAN has a finite, though quite large, capacity. The second is the nature of the disaster they can withstand. A hard drive failure, accidental data deletion, or similar small-scale incident will not prevent a redundant network server or SAN from continuing to provide data and services to end users. But what about an earthquake, flood, or fire that destroys the entire building, including the SAN? For quite some time, the only answer to that was an off-site backup network. If your primary network was destroyed, you moved operations to a backup network, with only minimal downtime. The duplicate backup site is called a “hot” site, “warm” site, or “cold” site, ranging from failover with little to no downtime to a site that has parts ready to be made operational.

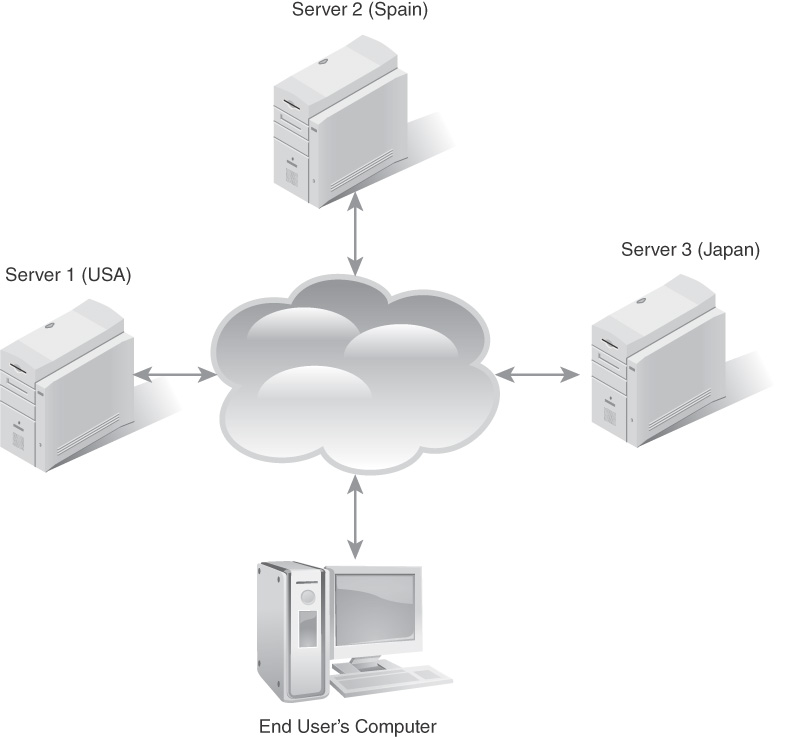

Eventually, the idea was formed to take the idea of a SAN and the idea of off-site backup networks and combine them. When a company hosts a cloud, it establishes multiple servers, possibly in diverse geographic areas, with data being redundantly stored on several servers. There may be a server in New York, another in San Francisco, and another in London. The end user simply accesses the cloud without even knowing where the data actually is. It is hard to imagine a scenario wherein the entire cloud would be destroyed. The basic architecture of a cloud is shown in FIGURE 14-1.

FIGURE 14-1

The cloud.

What Impact Does Cloud Computing Have on Forensics?

Cloud computing, in which resources, services, and applications are located remotely instead of on a local server, affects digital forensics in several ways. First and foremost, it makes data acquisition more complicated. If a website is the target of a crime and the server must be forensically examined for evidence, how do you collect evidence from a cloud? Fortunately, each individual hosted server is usually in a separate virtual machine. The process, then, is to image that virtual machine, just as you would image any other hard drive. It does not matter if the virtual machine is duplicated or distributed across a cloud. However, a virtual machine is hosted on a host server. That means that in addition to the virtual machine’s logs, you will need to retrieve the logs for the host server or servers.

Another issue in cloud forensics involves the legal process. Because a cloud could potentially reach across multiple states or even nations, the investigator must be aware of the rules of seizure, privacy, and so forth in each location from which he or she will retrieve data. It is very common for criminal enterprises to intentionally construct their own clouds with data stored in jurisdictions with rules and laws that make data retrieval for the purpose of forensics difficult or impossible. With the growing popularity of cloud computing, these issues are likely to become more common in the coming years. This is why it is important for a forensic investigator to have at least some familiarity with laws related to computer forensics, even in other countries.

New Devices

Although it is true that computers are advancing and becoming more powerful every year, that is not the only challenge facing forensics. Another important issue is the emergence of new devices. Consider smartphones and tablets, which are both relatively new devices. With any new computing device, it is safe to assume that it will eventually be the target of a forensic investigation.

Google Glass

Google Glass emerged on the market in 2013. Although it failed commercially, the technology is sound and is likely to reappear in the future. It is certain that at least something like it will be in wide use in the coming years. This should make any forensic investigator curious as to the specifics of Google Glass.

Google Glass includes permanent storage via a small hard drive. It has the ability to record images and video. At a minimum, Google Glass could contain photographic or video evidence of a crime. The operating system is Android, which is Linux-based. This means that once you connect to Google Glass from your forensic workstation, you can execute Linux commands to create an image of the Google Glass partition. After the partition is imaged, it can be examined forensically, just as any Linux partition would be.

Cars

For several years, cars have become increasingly sophisticated. Global positioning system (GPS) devices within cars are now commonplace. Many vehicles have hard drives to store and play music. These technological advances can also be repositories for forensic evidence. For example, GPS data might establish that a suspect’s car was at the scene of a crime when the crime took place. That alone would not lead to a conviction, but it does help to build a case. In recent years there has been a growing list of successful car hacking incidents. In those cases, the car itself is the crime scene.

Medical Devices

An increasing number of medical devices are built to communicate; for example, there are insulin pumps that send data regarding usage to a computer via a wireless connection. There are pacemakers that operate similarly. This leads to the question of whether medical wireless communications can be compromised. The unfortunate fact is they can be. Multiple news sources have carried the story of a researcher who discovered he could hack into wireless insulin pumps and alter the dosage, even to fatal levels.

With the increasing complexity of medical devices, it could eventually become commonplace to forensically examine them in cases where foul play is suspected—just as it is now commonplace to forensically examine any phone seized in relation to a crime.

Augmented Reality

As I write this chapter, the phone game Pokémon is quite popular. The game involves an app that can allow the user to “see” Pokémon characters superimposed on the image of the real world. The player then “captures” the characters. Although this game has no direct impact on forensics, it is the first widespread use of augmented reality. It is clear that more applications that fuse the digital world with the real world will be forthcoming. This blurs the line between the digital and the physical, and will have implications for forensics.