The Registry

What is the Registry? It is a repository for all the information on a Windows system. When you install a new program, its configuration settings are stored in the Registry. When you change the desktop background, that is also stored in the Registry.

According to a Microsoft TechNet article by Joan Bard:

With few exceptions, all 32-bit Windows programs store their configuration data, as well as your preferences, in the Registry, while most 16-bit Windows programs and MS-DOS programs don’t—they favor the outdated INI files (text files that 16-bit Windows used to store configuration data) instead. The Registry contains the computer’s hardware configuration, which includes Plug and Play devices with their automatic configurations and legacy devices. It allows the operating system to keep multiple hardware configurations and multiple users with individual preferences. It [The Registry] allows programs to extend the desktop with such items as shortcut menus and property sheets. It supports remote administration via the network. Of course, there’s more. But this serves as a good introduction to what the Registry does.

As you will see in this section, there is a great deal of forensic information you can gather from the Registry, which is why it is important to have a thorough understanding of Registry forensics. But, first, how do you get to the Registry? The usual path is through the tool regedit. In Windows 10 and Server 2016, you select Start, then Run, and then type in regedit. In Windows 8, you need to go to the applications list, select All Apps, and then find regedit.

The Registry is organized into five sections referred to as hives. Each of these sections contains specific information that can be useful to you. The five hives are described here:

HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT (HKCR)—This hive stores information about drag-and-drop rules, program shortcuts, the user interface, and related items.

HKEY_CURRENT_USER (HKCU)—This hive is very important to any forensic investigation. It stores information about the currently logged-on user, including desktop settings, user folders, and so forth.

HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE (HKLM)—This hive can also be important to a forensic investigation. It contains those settings common to the entire machine, regardless of the individual user.

HKEY_USERS (HKU)—This hive is very critical to forensic investigations. It has profiles for all the users, including their settings.

HKEY_CURRENT_CONFIG (HCU)—This hive contains the current system configuration. This might also prove useful in your forensic examinations.

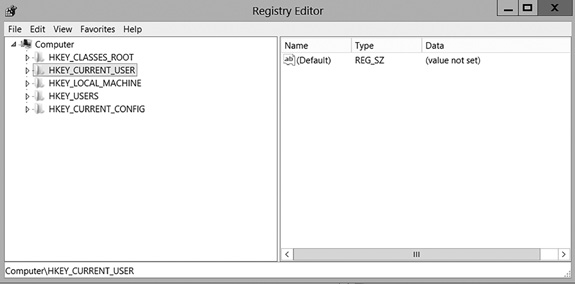

FIGURE 8-9

The Windows Registry.

Used with permission from Microsoft

You can see these five hives in FIGURE 8-9.

As you move forward in this section and learn where to find certain critical values in the Registry, keep in mind the specific hive names.

All Registry keys contain a value associated with them called LastWriteTime. You can think of this like the modification time on a file or folder. Looking at the LastWriteTime tells you when this Registry value was last changed. Rather than being a standard date/time, this value is stored as a FILETIME structure. A FILETIME structure represents the number of 100-nanosecond intervals since January 1, 1601.

Before you learn about specific evidence found in the Registry, consider a few general settings that can be useful. Auto-run locations are Registry keys that launch programs automatically during boot-up. It is common for viruses and spyware to be automatically run at start-up. Another setting to look at is the MRU, or most recently used. These are program specific; for example, Microsoft Word might have an MRU describing the most recently used documents.

A typical Registry key may contain up to four subentries, labeled “ControlSet” (The four you may encounter are listed here:

\ControlSet001—The last control set Windows booted with.

\ControlSet002—The last known good control set, or the control set that last successfully booted Windows. If all went well at boot-up, then ControlSet001 and ControlSet002 should be identical.

\CurrentControlSet—A pointer to either the ControlSet001 or ControlSet002 key.

\Clone—A clone of CurrentControlSet; it is created each time you boot your computer.

In an ideal situation, all of these will contain identical information. Any discrepancy should be noted and investigated.

USB Information

One important thing you can find in the Registry is any USB devices that have been connected to the machine.

The Registry key HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\System\ControlSet\Enum\USBTOR lists USB devices that have been connected to the machine. It is often the case that a criminal will move evidence or exfiltrate other information to an external device and take it with him or her. This could indicate to you that there are devices you need to find and examine. Often, criminals attempt to move files offline onto an external drive. This Registry setting tells you about the external drives that have been connected to this system.

There are other keys related to USBSTOR that provide related information. For example, SYSTEM\MountedDevices allows investigators to match the serial number to a given drive letter or volume that was mounted when the USB device was inserted. This information should be combined with the information from USBSTOR in order to get a more complete picture of USB-related activities.

The Registry key \Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\Mount-Points2 will indicate which user was logged onto the system when the USB device was connected. This allows the investigator to associate a specific user with a particular USB device.

Wireless Networks

Think, for just a moment, about connecting to a Wi-Fi network. You probably had to enter some passphrase. But you did not have to enter that passphrase the next time you connected to that Wi-Fi, did you? That information is stored somewhere on the computer, but where? It is stored in the Registry.

When an individual connects to a wireless network, the service set identifier (SSID) is logged as a preferred network connection. This information can be found in the Registry in the HKLM \SOFTWARE\Microsoft\WZCSVC\Parameters\Interfaces key.

The Registry key HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\ NetworkList\Profiles\ gives you a list of all the Wi-Fi networks to which this network interface has connected. The SSID of the network is contained within the Description key. When the computer first connected to the network is recorded in the DateCreated field.

The Registry key HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\WindowsNT\CurrentVersion\ NetworkList\Signatures\Unmanaged \{ProfileGUID} stores the MAC address of the wireless access point to which it was connected.

Tracking Word Documents in the Registry

Many versions of Word store a PID_GUID value in the Registry—for example, something like: { 1 2 3 A 8 B 2 2-6 2 2 B-1 4 C 4-8 4 A D-0 0 D 1 B 6 1 B 0 3 A 4 }. The string 0 0 D 1 B 6 1 B 0 3 A 4 is the MAC address of the machine on which this document was created. In cases involving theft of intellectual property, espionage, and similar crimes, tracking the origin of a document can be very important. This is a rather obscure aspect of the Windows Registry that is not well known, even among forensic analysts.

Malware in the Registry

If you search the Registry and find HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\WindowsNT\ CurrentVersion\Winlogon, it has a value named Shell with default data Explorer.exe. Basically, it tells the system to launch Windows Explorer when the logon is completed. Some malware append the malware executable file to the default values data, so that the malware will load every time the system launches. It is important to check this Registry setting if you suspect malware is an issue.

The key HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services\ lists system services. There are several examples of malware that install as a service, particularly backdoor software. So again, check this key if you suspect malware is an issue.

Uninstalled Software

An intruder who breaks into a computer might install software on that computer for various purposes, such as recovering deleted files or creating a back door. The intruder will then, most likely, delete the software used. It is also possible that an employee who is stealing data might install steganography software to hide the data and will subsequently uninstall that software. The HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Uninstall key lets you see all the software that has been uninstalled from this machine. This is a very important Registry key for any forensic examination.

Passwords

If the user tells Internet Explorer to remember passwords, then those passwords are stored in the Registry and you can retrieve them. The following key holds these values:

HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Internet Explorer\IntelliForms\SPW

Note in some versions of Windows the ending will be \IntelliForms\Storage 1.

Any source of passwords is particularly interesting. It is not uncommon for people to reuse passwords. Therefore, if you are able to obtain passwords used in one context, they may be the same passwords used in other contexts.

ShellBag

This entry can be found at HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Shell\Bags. ShellBag entries indicate a given folder was accessed, not a specific file. This Windows Registry key is of particular interest in child pornography investigations. It is common for a defendant to claim he or she was not aware those files were on the computer in question. The ShellBag entries can confirm or refute that claim.

A good resource for more information on the Windows Registry can be found at the Sans Institute Infosec Reading Room at http://www.sans.org/reading_room/whitepapers/auditing/wireless-networks-windows-registry-computer-been_33659.

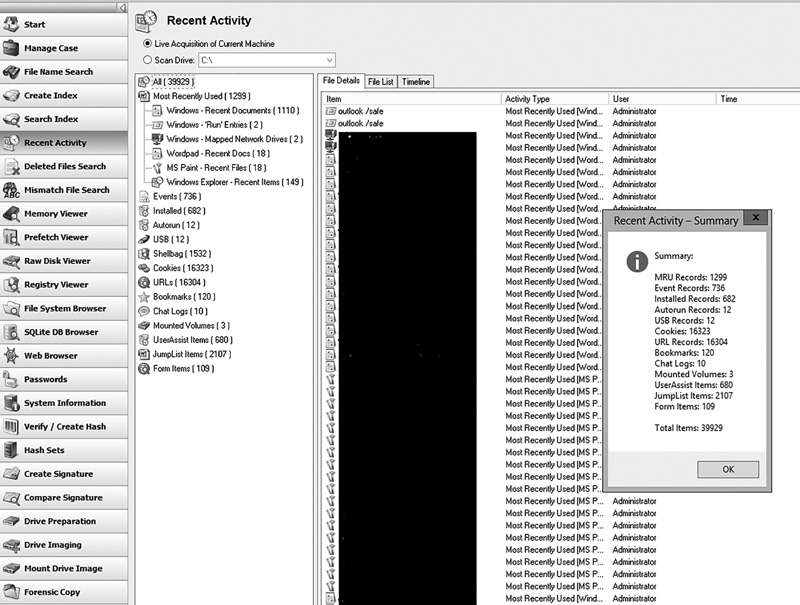

The forensics tool OSForensics brings together many different Windows Registry values into a single screen named “Recent Activity.” This is shown in FIGURE 8-10. Note that actual file names are redacted; this image was taken from my own computer. However, you can see that this tool provides the forensic examiner with a very easy-to-view output showing ShellBags, Internet history, UserAssist, USB devices, and other important information from the Windows Registry.

FIGURE 8-10

OSForensics recent activity.

Courtesy of PassMark Software

Prefetch

Prefetch is a technique introduced in Windows XP. Most, if not all, Windows programs depend on a range of dynamic-link libraries (DLLs) to function. To speed up the performance of these programs, Windows keeps a list of all the DLLs a given executable needs. When the executable is launched, all the DLLs are “fetched.” The intent is to speed up software, but a side benefit is that the prefetch entry keeps a list of how many times an executable has been run, and the last date/time it was run. Most Windows forensics tools will pull this information for you. OSForensics makes it part of the “Recent Activity.”