Network Packet Analysis

It is important for any forensic analyst to be able to analyze network traffic. Many attacks are live attacks on a network, such as denial of service (DoS) attacks. In this section, you will learn more about network packets, network-based attacks, and tools for analyzing network traffic.

Network Packets

Information that is sent across a network is divided into chunks, called packets. Technically speaking, packets exist in the Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) model at Layer 3 and are typically formatted according to the Internet Protocol (IP)—though many other protocols and their unique formats may also be encountered. Packets are divided into two parts: the header and the payload. If you think in terms of an envelope, the header contains the address information (to and from and any special handling), and the payload contains the content of the letter.

Packet Header

A unit of information being transferred can have several headers put on by different protocols at different layers of the OSI model. There is usually an Ethernet header from Layer 2, an IP header from Layer 3, a Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) header from Layer 5, and then appropriate higher-layer headers above that. Each contains different information. Combined, they have several pieces of information that will interest forensic investigations:

The Ethernet header has the source and destination Media Access Control (MAC) address. The source MAC address you receive will be the source MAC address of the last switch before the packet reached you. It won’t be the MAC address of the actual original sender.

The IP header contains the source IP address, the destination IP address, and the protocol number of the protocol in the IP packet’s payload. These are critical pieces of information.

The TCP header contains the source port, destination port, a sequence number, and several other fields. The sequence number is very important to network traffic; for example, knowing this is packet 4 of 10 is important. The TCP header also has synchronization bits that are used to establish and terminate communications between both communicating parties.

It is also possible that certain types of traffic will have a User Datagram Protocol (UDP) header instead of a TCP header. A UDP header still has a source and destination port number, but it lacks a sequence number and synchronization bits.

The issue of synchronization bits in the TCP header can also yield interesting forensic data. Here are the bits most often used and what they indicate:

URG (1 bit)—Traffic is marked as urgent, though this bit is rarely used. It is more common that the IP precedence bits are used for priority when there is a need.

ACK (1 bit)—This bit acknowledges the attempt to synchronize communications.

RST (1 bit)—The RST bit resets the connection.

SYN (1 bit)—This bit synchronizes sequence numbers.

FIN (1 bit)—This bit indicates there is no more data from the sender.

A normal network conversation starts with one side sending a packet with the SYN bit turned on. The target responds with both the SYN and ACK bits turned on. Then, the other end responds with just the ACK bit turned on. Then, after this “three-way handshake,” communication commences. When it is finished sending information, the connection is terminated by sending a packet with the FIN bit turned on.

There are some attacks that depend on sending malformed packets. For example, some session hijacking attacks begin with sending an RST packet to attempt to reset the connection so the attacker can take over. The SYN flood denial of service (DoS) attack is based on flooding the target with SYN packets but never responding to the SYN/ACK that is sent back.

Keep in mind that most skilled hackers start by performing reconnaissance on the target system. One of the first steps in that process is to do a port scan. Many port-scanning tools are available on the Web. The most primitive of these just send an Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP) packet to each port in order to see if they respond. But because this is rather obviously a port scan, and some administrators block incoming ICMP packets, hackers have become more sophisticated. There are several stealthier scans, based on manipulating the aforementioned bit flags in packet headers. Seeing incoming packets destined for well-known ports, like the ones listed previously, with certain flags (bits) turned on, is a telltale sign of a port scan. Here is a brief description of some of the more common scans so you will know what to look for:

FIN scan—A packet is sent with the FIN flag turned on. If the port is open, this generates an error message. Remember that FIN indicates the communication is ended. Because there was no prior communication, an error is generated telling the hacker that this port is open and in use.

Christmas tree scan—The Christmas tree scan sends a TCP packet to the target with the URG, PUSH, and FIN flags set. This is called a Christmas tree scan because of the alternating bits turned on and off in the flags byte.

Null scan—The null scan turns off all flags, creating a lack of TCP flags in the packet. This would never happen with real communications. It, too, normally results in an error packet being sent.

This means when you are examining TCP/IP packet headers, you need to look at the ports, IP address, and bit flags. You may also find useful information in the MAC address in the lower-layer part of the information transfer unit. This is in addition to searching the actual data in the packets.

Payload

The payload is the body or information content of a packet. This is the actual content that the packet is delivering to the destination. If a packet is fixed length, the payload may be padded with blank information or a specific pattern to make it the right size.

Trailer

The TCP (OSI model Layer 4) and IP (OSI model Layer 3) portions of a unit of information transfer contain only a header and payload. However, if the Layer 2 portion of a unit of information transfer is analyzed, then in addition to a header and payload, there is also a part at the end called the trailer. The trailer may be part of the Ethernet or Point-to-Point Protocol (PPP) frame or other Layer 2 protocol, often called Data Link Layer protocol. An Ethernet frame, for instance, has 96 bits that tell the receiving device that it has reached the end of the transmission. A Layer 2 frame also has error checking.

Ethernet uses a 32-bit cyclic redundancy check (CRC). The sender calculates the CRC using a very complex calculation on the source address, destination address, length, payload, and pad, if any. The four-octet (32-bit) result is stored in the trailer by the sender, and the frame is transmitted. The receiving device repeats the exact same calculation as the sender and compares the result with the value stored in the trailer. If the values match, the frame is good and the frame is processed. But if the values do not match, the receiving device has a decision to make. The decision is made consistently based on the protocol involved. In the case of Ethernet, the receiver discards the errored frame and sends no indication whatsoever that the frame has been discarded. The receiver usually does, however, update some internal counter, which can be queried to say how many frames were discarded. There is also a counter that says how many frames arrived and passed the CRC.

Ethernet relies on the fact that an upper-layer protocol may or may not request a retransmission of the errored frame or may or may not do something else, based on how the protocol works. Likewise, in the case of Internet Protocol, there is neither a retransmission request for an errored or missing frame, nor a retransmission request in the UDP protocol. TCP, on the other hand, does request a retransmission. If a frame does not pass the CRC check of Ethernet, it is discarded. TCP knows that Ethernet discarded a frame because of the sequence number in the TCP header. If a lower-level frame is discarded and therefore is missing from the sequence, then TCP will request a retransmission. It will also usually request a retransmission in the case of a sequence error.

Ports

A port is a number that identifies a channel in which communication can occur. Just as your television may have one cable coming into it but many channels you can view, your computer may have one cable coming into it but many network ports on which you can communicate. There are 65,635 possible ports, divided into three distinct types, and some are used more often than others. There are certain ports a forensic analyst should know on sight. Knowing what port a packet was destined for (or coming from) will tell you what protocol it was using, which can be invaluable information. The IP address concatenated with a port number is called a socket and will be unique for the duration of a connection. The following is a list of the ports you should memorize and the protocols that normally use those ports:

20 and 21—File Transfer Protocol (FTP) for transferring files between computers. Port 20 is for information; port 21 is for control.

22—Secure Shell (SSH) to remotely and securely log on to a system. You can then use a command prompt or shell to execute commands on that system. This port is popular with network administrators and more secure than Telnet.

23—Telnet to remotely log on to a system. You can then use a command prompt or shell to execute commands on that system. SSH is preferred for its greater security.

25—Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) to send email.

43—Whois, a command that queries a target IP address for information.

53—Domain Name Service (DNS) to translate uniform resource locators (URLs) into web addresses and possibly retrieve other information about the system that matches the URL.

69—Trivial File Transfer Protocol (TFTP), which is a faster version of FTP.

80—Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) to display webpages.

88—Kerberos authentication.

110—Post Office Protocol Version 3 (POP3) to retrieve email.

137–139—NetBIOS.

143—The Internet Message Access Protocol (IMAP) email service. Note that IMAP can also use port 220.

161 and 162—Simple Network Management Protocol (SNMP).

179—Border Gateway Protocol (BGP).

194—Internet Relay Chat (IRC) chat rooms.

389—Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP) user authentication.

443—Hypertext Transfer Protocol, Secure (HTTPS) secure webpage display.

445—Active Directory/Server Message Block (SMB) protocol.

464—Kerberos change password.

465—Simple Mail Transfer Protocol over Secure Sockets Layer (SMTP over SSL) to secure email sending.

636—Lightweight Directory Access Protocol, Secure (LDAPS) (SSL or TLS).

993—Secure IMAP, encrypted IMAP

995—POP3 Secure, encrypted POP3

3389—Remote Desktop

31337—Back Orifice (malware).

54320 and 54321—BO2K (malware).

6666—Beast (malware).

23476 and 23477—Donald Dick (malware).

43188—Reachout (malware).

407—Timbuktu (remote desktop application).

Why should you know these ports? Consider the information you gather from them. Assume you capture traffic going to and from a database server on port 21. This means someone is using FTP to upload or download files with that server, but you query the network administrator and find he or she doesn’t use FTP on his or her database server. This is likely a sign of an intruder or, at the very least, of an insider who is not adhering to system policy. Or, perhaps you see frequent attempts to connect to a web server on port 23 (Telnet). An old hacker trick is to attempt to Telnet into a web server and grab the server’s banner or banners. This allows the hacker to determine the exact operating system and web server running, unless the system administrator has modified the banner to avoid such a well-known hacker trick.

The last six items on the preceding list (starting with Back Orifice) may seem strange. The names are certainly a bit odd. These are all utilities that give an intruder complete access to the target system. Only one of them, Timbuktu, has any legitimate use. Timbuktu is an open source alternative to PC Anywhere. It allows program users to log on to a remote system and work just like they were sitting in front of the desktop. It is possible that technical support personnel are using Timbuktu to make support calls more efficient. But it is also possible that an intruder is logging on and taking over the system. The other five items are simply examples of backdoor hacker software with no legitimate use. The list is not intended to be exhaustive—there are many more hacker programs, and new ones appear every day.

As you can see, just knowing ports and seeing the ports in the TCP or UDP headers can yield very valuable evidence. The next step is to start tracking down the source IP address. Assuming it is not a spoofed IP address, this may lead you directly to the culprit.

Network Attacks

Certain computer attacks actually strike at the network itself rather than at a specific machine that is attached to the network. In some cases, these attacks are directed at a specific machine or machines but have an impact on the network itself. A few of those attacks are discussed here.

Denial of Service

This is the classic example of a network attack. A DoS attack can be targeted at a given server, but usually the increased traffic affects the rest of the target network. In a DoS attack, the attacker uses one of three approaches. The attacker can damage the target machine’s ability to operate, overflow the target machine with too many open connections at the same time, or use up the bandwidth to the target machine. In a DoS attack, the attacker usually floods the network with malicious packets, preventing legitimate network traffic from passing. The following sections discuss specific types of DoS attacks.

Ping of death attack

In a ping of death attack, an attacker sends an ICMP echo packet of a larger size than the target machine can accept. At one time, this form of attack caused many operating systems to lock or crash, until vendors released patches to deal with ping of death attacks. Firewalls can be configured to block incoming ICMP packets completely or to block ICMP packets that are malformed or of an improper length, which is typically 84 bytes, including the IP header.

Ping flood

Related to the ping of death is the ping flood. The ping flood simply sends a tremendous number of ICMP packets to the target, hoping to overwhelm it. This attack is ineffective against modern servers. It is just not possible to overwhelm a server, or even most workstations, with enough pings to render the target unresponsive. But when executed by a large number of coordinated source computers against a single target computer, this attack can be very effective. This second variety of ping flood falls into the category called a distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack.

Teardrop attack

In a teardrop attack, the attacker sends fragments of packets with bad values in them, which cause the target system to crash when it tries to reassemble the fragments. Like the ping of death attack, the teardrop attack has been around long enough for vendors to have released patches to avoid it.

SYN flood attack

In a SYN flood attack, the attacker sends unlimited synchronize (SYN) requests to the host system. The attacker’s system is supposed to respond to the SYN requests, which are the first step in initiating communication, but it doesn’t. Essentially, the attacker sends the target the starting SYN request. This causes the server to set up some resources to handle the connection and respond to the client with both the SYN and ACK bits turned on, acknowledging the synchronization request. The attacker is supposed to respond with the ACK bit turned on. In this attack, the attacker just floods the target with SYN packets, never responding. This can overwhelm the target system with phantom connection requests and render it unable to respond to legitimate requests.

Most modern firewalls can block this attack. This is because most modern firewalls look at the entire “conversation” between client and server, not just each individual packet. So although a single packet with the SYN bit turned on from a specific client is totally normal traffic, 100,000 such packets in under five minutes is not and will be blocked. However, in the game of chess that is modern cybersecurity, the attacker can change the IP address and even the MAC address of his or her attack information to get around such blocking. Remember that the objective is to tie up resources on the target system such that a target system cannot process legitimate requests in a timely fashion or cannot process them at all.

Land attack

In a land attack, the attacker sends a fake TCP SYN packet with the same source and destination IP addresses and ports as the target computer. Basically, the computer is tricked into thinking it is sending messages to itself because the packets coming in from the outside are using the computer’s own IP address.

Smurf attack

A Smurf attack generates a large number of ICMP echo requests from a single request, acting like an amplifier. The responses back to the target victim cause a traffic jam in the target network. However, routing devices today very rarely accept broadcast requests; therefore, this attack is generally confined to a victim on the same network subnet. If computers on that network reply to each echo, each additional reply increases the traffic jam.

Fraggle attack

A fraggle attack is similar to a smurf attack, except that it uses spoofed UDP packets instead of ICMP echo replies. Fraggle attacks can often bypass a firewall.

Packet mistreating attack

A packet mistreating attack occurs when a compromised router mishandles packets. This type of attack results in congestion in a part of the network.

Network Traffic Analysis Tools

A sniffer is computer software or hardware that can intercept and log traffic passing over a digital network. Sniffers are used to collect digital evidence. Commonly applied sniffers include Wireshark (http://www.wireshark.org), useful on all platforms, Tcpdump (http://www.tcpdump.org/tcpdump_man.html) for various UNIX platforms, and WinDump (http://www.winpcap.org/windump/), which is a version of Tcpdump for Windows. These programs extract network packets and perform a statistical analysis on the dumped information.

Use them to measure response time, the percentage of packets lost, and TCP/UDP connection startup and end.

The following are some other popular tools for network analysis:

TShark (command line interface to Wireshark) can be found at http://www.wireshark.org.

CommView can be found at http://www.tamos.com/products/commview/.

Softperfect Network Protocol Analyzer can be found at http://www.softperfect.com.

HTTP Sniffer can be found at http://www.effetech.com/sniffer/.

ngrep can be found at http://sourceforge.net/projects/ngrep/.

OmniPeek can be found at http://www.savvius.com.

Some software tools for investigating network traffic include the following:

RSA NetWitness can be found under Threat Detection & Response Products at http://www.rsa.com.

NetResident can be found at http://www.tamos.com/products/netresident/.

Snort, an open source intrusion detection application, can be found at http://www.snort.org.

Nmap, the popular network scanner, can be found at http://www.nmap.org.

When collecting evidence on a network, it is vital to document what you’ve collected. Specifically, note in detail who collected the evidence, when it was collected, where it was collected, and how it was collected. Then analyze the evidence to construct a clearer picture of all activities that have occurred. If possible, organize the evidence by time and function.

A few of these tools bear a closer look.

Wireshark

Wireshark is a widely used packet sniffer. It is a free download at http://www.wireshark.org and available for several operating systems. It is very easy to use. The user simply selects an interface, or network card, and then starts the capture.

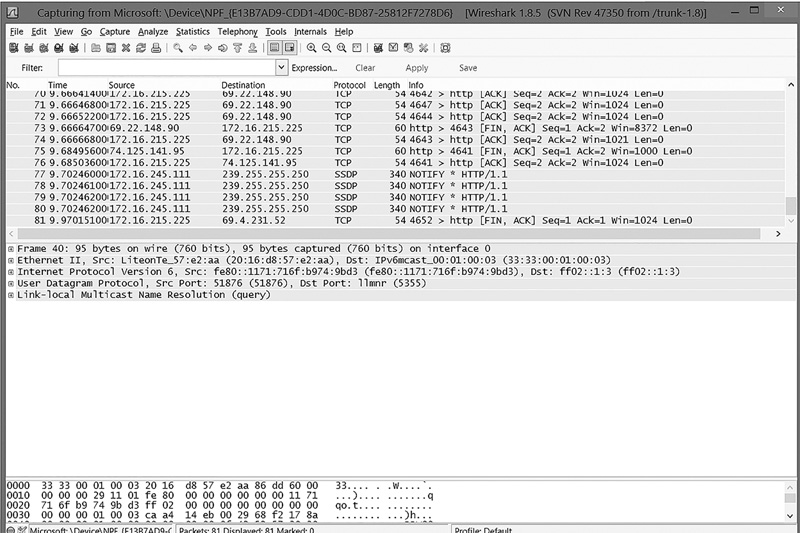

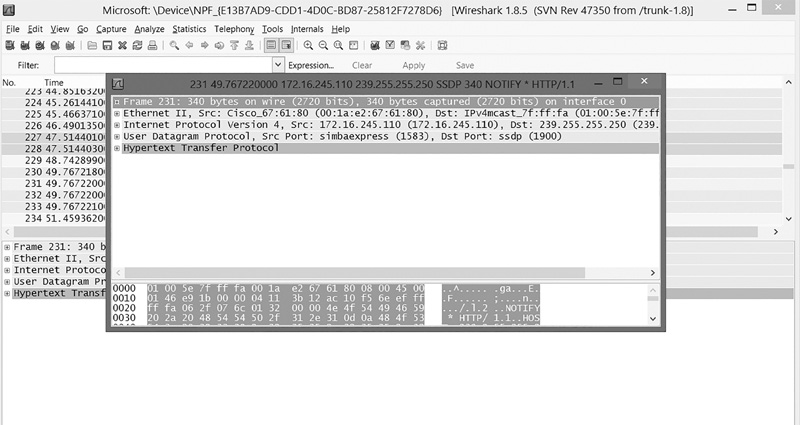

FIGURE 12-1 shows the three main panes of the Wireshark interface. At the top is the Packet List pane, then the Packet Details pane in the middle, and the Packet Bytes pane at the bottom. The Packet List pane shows the IP address the packets are coming from and going to, protocols identified based on port used, the time stamp, and many other useful pieces of information. The Packet Details pane shows details from any highlighted packet in the above pane. At any time, you can stop the packet-capture process and view the individual packets. Double-clicking on any given packet displays a pop-up box showing the details of that particular packet, an example of which is shown in FIGURE 12-2.

You can immediately see the source and destination MAC address, protocol, and source and destination IP addresses—if appropriate—and much more. Looking at the bottom Packet Bytes pane, you can see the data in the packet. The data is shown in two forms: hexadecimal, which is obviously not readable, and ASCII, which can be intelligible at times. If the packet is an image file, for instance, or is encrypted, you won’t be able to read much of what is displayed.

HTTPSniffer

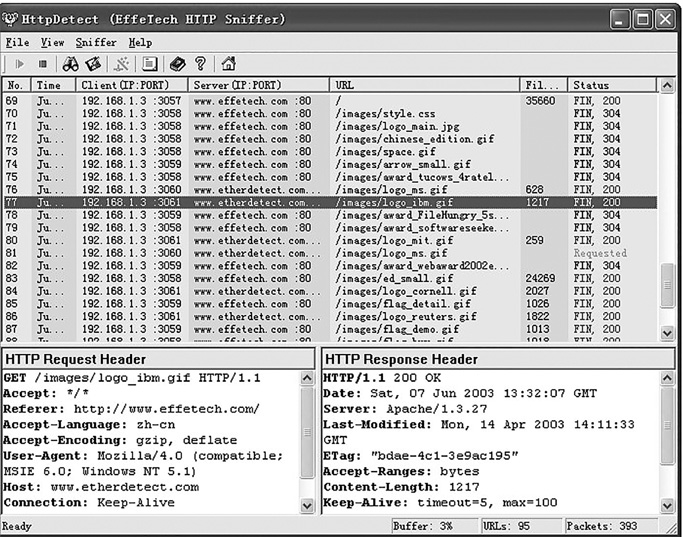

Much like Wireshark, this product is easy to use and has a free trial version. It is used specifically to capture web traffic. You can see all the HTTP commands going to the server and the responses from the server.

FIGURE 12-1

Wireshark packet capture.

Courtesy of the Wireshark Foundation.

FIGURE 12-2

Wireshark packet details.

Courtesy of the Wireshark Foundation.

This is a very simple and intuitive product, as seen in FIGURE 12-3. To properly interpret this data, you need to understand the basic HTTP commands, as well as the response codes. The HTTP commands are described in TABLE 12-1.

The most common commands are GET, HEAD, PUT, and POST. In fact, you might see only those four commands during most of your analysis of web traffic.

FIGURE 12-3

HTTPSniffer.

Courtesy of EffeTech.

|

TABLE 12-1 HTTP commands. |

|

HTTP COMMAND |

DESCRIPTION |

GET |

Request to read a webpage |

HEAD |

Request to read just the head section of a webpage |

PUT |

Request to write a webpage |

POST |

Request to append to a page |

DELETE |

Remove the webpage |

LINK |

Connect two existing resources |

UNLINK |

Break an existing connection between two resources |

The response codes are just as important. You have probably seen “Error 404 file not found,” but there are a host of messages going back and forth, most of which you don’t see. The messages are shown in TABLE 12-2.

The vendor also supplies an online Flash tutorial, which goes through the nuances of using this product. The tutorial can be found at http://www.effetech.com/sniffer/tutorial.htm.

Nmap

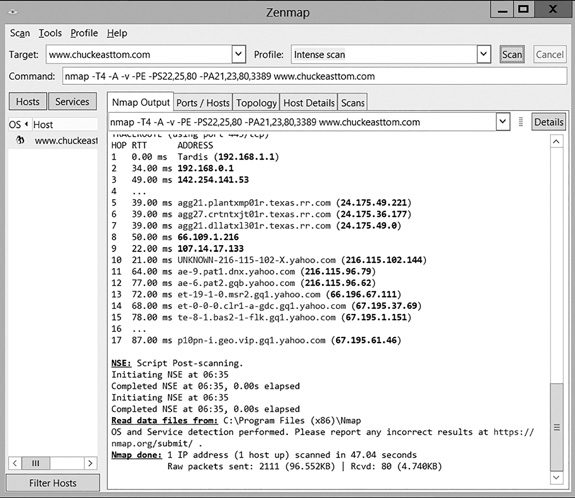

Nmap is popular with both network security administrators and hackers; an example is shown in FIGURE 12-4. It allows the user to map out which ports are open on a target system and which services are running. Nmap is a command-line tool, but it has a Windows interface called Zenmap that is available for free.

This tool is popular with hackers because it can be configured to operate rather stealthily and determine all open ports on an individual machine, or on all machines in an entire range of IP addresses. It is popular with administrators because of its ability to discover open ports on the network. Such ports could indicate spyware, a backdoor, or many other attacks.

Snort

Snort is primarily used as an open source intrusion detection system, but it can also function as a robust packet sniffer with a lot of configuration options. For full installation instructions, visit http://www.snort.org. They also offer a free manual at http://manual-snort-org.s3-website-us-east-1.amazonaws.com/ For network analysis, you want to run snort as a packet sniffer and configure it to log verbose data.

|

TABLE 12-2 HTTP response message. |

|

MESSAGE RANGE |

MEANING |

100–199 |

These are just informational. The server is giving your browser some information, most of which will never be displayed to the user. For example, when you switch from HTTP to HTTPS, a 101 message goes to the browser telling it that the protocol is changing. |

200–299 |

These are basically “OK” messages, meaning that whatever the browser requested, the server successfully processed. |

300–399 |

These are redirect messages telling the browser to go to another URL. For example, 301 means that the requested source has permanently moved to a new URL, whereas message 307 indicates the move is temporary. |

400–499 |

These are client errors, and the ones most often shown to the end user. 404 means file not found. You may be puzzled—how is a file not found a client error? It is because the client requested a page that does not exist. The server processed the request without problem, but the request was invalid. |

500–599 |

These are server-side errors. For example, 503 means the service requested is down, possibly overloaded. You will see this error frequently in DoS attacks. |

FIGURE 12-4

Nmap.

Courtesy of Nmap.org.

RSA NetWitness

This is a product from RSA that has a freeware version at http://www.rsa.com. It is definitely worth taking a look at, but this product is not nearly as easy to use as Wireshark.