What Is Computer Forensics?

Before you can answer the question, “What is computer forensics?” you should address the question, “What is forensics?” The American Heritage Dictionary defines forensics as “the use of science and technology to investigate and establish facts in criminal or civil courts of law.”

Essentially, forensics is the use of science to process evidence so you can establish the facts of a case. The individual case being examined could be criminal or civil, but the process is the same. The evidence has to be examined and processed in a consistent scientific manner. This is to ensure that the evidence is not accidentally altered and that appropriate conclusions are derived from that evidence.

You have probably seen some crime drama wherein forensic techniques were a part of the investigative process. In such dramas, a bullet is found and forensics is used to determine the gun that fired the bullet. Or, perhaps a drop of blood is found and forensics is used to match the DNA to a suspect. These are all valid aspects of forensics. However, our modern world is full of electronic devices with the capacity to store data. The extraction of that data in a consistent scientific manner is the subject of computer forensics.

The Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT) defines computer forensics in this manner:

Forensics is the process of using scientific knowledge for collecting, analyzing, and presenting evidence to the courts.… Forensics deals primarily with the recovery and analysis of latent evidence. Latent evidence can take many forms, from fingerprints left on a window to DNA evidence recovered from blood stains to the files on a hard drive.

According to the website Computer Forensics World:

Generally, computer forensics is considered to be the use of analytical and investigative techniques to identify, collect, examine and preserve evidence/information which is magnetically stored or encoded.

The objective in computer forensics is to recover, analyze, and present computer-based material in such a way that it can be used as evidence in a court of law. In computer forensics, as in any other branch of forensic science, the emphasis must be on the integrity and security of evidence. A forensic specialist must adhere to stringent guidelines and avoid taking shortcuts.

Any device that can store data is potentially the subject of computer forensics. Obviously, that includes devices such as network servers, personal computers, and laptops.

It must be noted that computer forensics has expanded. The topic now includes cell phone forensics, router forensics, global positioning system (GPS) device forensics, tablet forensics, and forensics of many other devices. The term digital forensics is a more encompassing term that includes all of these devices. Regardless of the term you use, the goal is the same: to apply solid scientific methodologies to a device in order to extract evidence for use in a court proceeding.

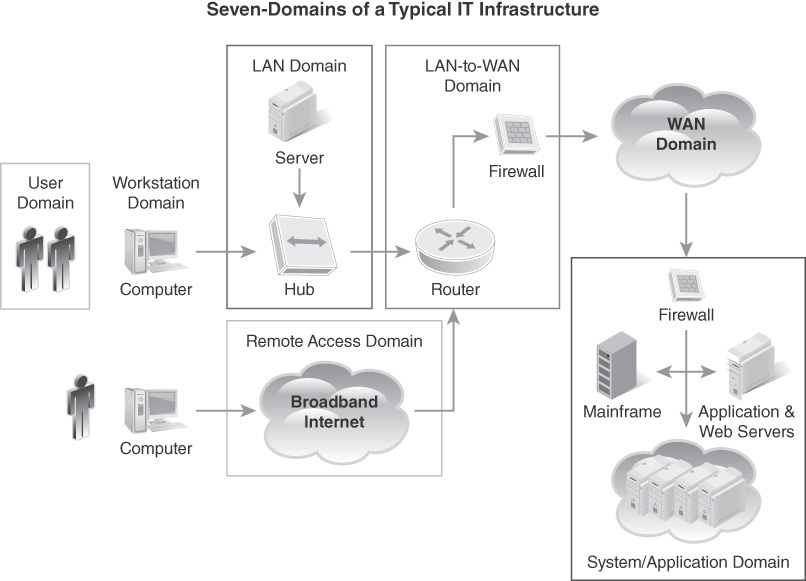

Although the subject of computer forensics, as well as the tools and techniques used, is significantly different from traditional forensics—like DNA analysis and bullet examination—the goal is the same: to obtain evidence that can be used in some legal proceeding. Computer forensics applies to all the domains of a typical IT infrastructure, from the User Domain and Remote Access Domain to the Wide Area Network (WAN) Domain and Internet Domain (see FIGURE 1-1).

FIGURE 1-1

The seven domains of a typical IT infrastructure.

Consider some elements of the preceding definitions. In particular, let’s look at this sentence: “Forensics is the process of using scientific knowledge for collecting, analyzing, and presenting evidence to the courts.” Each portion of this is critical, and the following sections of this chapter examine each one individually.

Using Scientific Knowledge

First and foremost, computer forensics is a science. This is not a process based on your “gut feelings” or personal whim. It is important to understand and apply scientific methods and processes. It is also important that you have knowledge of the relevant scientific disciplines. That also means you must have scientific knowledge of the field. Computer forensics begins with a thorough understanding of computer hardware. Then you need to understand the operating system running on that device; even smartphones and routers have operating systems. You must also understand at least the basics of computer networks.

If you attempt to master forensics without this basic knowledge, you are not likely to be successful. Now if you find yourself starting in on a course and are not sure if you have the requisite knowledge, don’t panic. First, you simply need a basic knowledge of computers and computer networks. If you have taken a couple of basic computer courses at a college or perhaps the CompTIA A+ certification, you have the baseline knowledge. Also, you will get a review of some basic concepts in this chapter.

However, the more you know about computers and networks, the better you will be at computer forensics. There is no such thing as “knowing too much.” Even though some technical details change quickly, such as the capacity and materials of hard disks, other details change very slowly, if at all, such as the various file systems, the role of volatile and nonvolatile memory, and the fact that criminals take advantage of the advancements in computer and digital technology to improve their lives as much as the businessman, student, or homeowner. A great deal of information is stored in computers. Keep learning what is there, where it is stored, and how that information may be used by computer user and computer criminal alike.

Collecting

Before you can do any forensic analysis or examination, you have to collect the evidence. There are very specific procedures for properly collecting evidence. You will be introduced to some general guidelines later in this chapter. The important thing to realize for now is that how you collect the evidence determines if that evidence is admissible in a court.

Analyzing

This is one of the most time-consuming parts of a forensic investigation, and it can be the most challenging. Once you have collected the data, what does it mean? The real difference between a mediocre investigator and a star investigator is the analysis. The data is there, but do you know what it means? This is also related to your level of scientific knowledge. If you don’t know enough, you may not see the significance of the data you have.

You also have to be able to solve puzzles. That is, in essence, what any forensic investigation is. It is solving a complex puzzle—putting together the data you have and finding out what sort of picture is revealed. You might try to approach a forensic investigation like Sherlock Holmes. Look at every detail. What does it mean? Before you jump to a conclusion, how much evidence do you have to support that conclusion? Are there alternatives and, in fact, better explanations for the data?

Presenting

Once you have finished your investigation, done your analysis, and obeyed all the rules and guidelines, you still have one more step. You will have to present that evidence in one form or another. The two most basic forms are the expert report and expert testimony. In either case, it will be your job to interpret the arcane and seemingly impenetrable technical information using plain English that paints an accurate picture for the court. You must not use jargon and technobabble. Your clear use of language, and potentially graphics and demonstrations, if needed, may be the difference between a big win and a lost case. So you should take a quick look at each of these.

The Expert Report

An expert report is a formal document that lists what tests you conducted, what you found, and your conclusions. It also includes your curriculum vitae (CV), which is like a résumé, only much more thorough and specific to your work experience as a forensic investigator. Specific rules will vary from court to court, but as a general rule, if you don’t put it in your report, you cannot testify about it at trial. So you need to make very certain that your report is thorough. Put in every single test you used, every single thing you found, and your conclusions. Expert reports tend to be rather long.

It is also important to back up your conclusions. As a general rule, it’s good to have at least two to three references for every conclusion. In other words, in addition to your own opinion, you want to have a few reputable references that either agree with that conclusion or provide support for how you came to that conclusion. This way, it is not just your expert opinion, but it is supported by other reputable sources. Make sure you use reputable sources; for example, CERT, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the Secret Service, and the Cornell University Law School are all very reputable sources.

The reason for this is that in every legal case there are two sides. The opposing side will have an attorney and perhaps its own expert. The opposing attorney will want to pick apart every opinion and conclusion you have. If there is an opposing expert, he or she will be looking for alternative interpretations of the data or flaws in your method. You have to make sure you have fully supported your conclusions.

It should be noted that the length and level of detail found in reports varies. In many cases, criminal courts won’t require a formal expert report, but rather a statement from the attorney as to who you are and what topics you intend to testify about. You will need to produce a report of your forensic examination. In civil court, particularly in intellectual property cases, the expert report is far more lengthy and far more detailed. In my own experience, reports of 100, 200, or more pages are common. The largest I have seen yet was over 1500 pages long.

Although not all cases will involve a full, detailed expert report, many will, particularly intellectual property cases. There are few legal guidelines on expert report writing, but a few issues have become clear in my experience.

Expert reports generally start with the expert’s qualifications. This should be a complete curriculum vitae detailing education, work history, and publications. Particular attention should be paid to elements of the expert’s history that are directly related to the case at hand. Then the report moves on to the actual topic at hand. An expert report is a very thorough document. It must first detail exactly what analysis was used. How did the expert conduct his or her examination and analysis? In the case of computer forensics, the expert report should detail what tools the expert used, what the results were, and the conditions of the tests conducted. Also, any claim an expert makes in a report should be supported by extrinsic reputable sources. This is sometimes overlooked by experts because they themselves are sources who are used, or because the claim being made seems obvious to them. For example, if an expert report needs to detail how domain name service (DNS) works in order to describe a DNS poisoning attack, then there should be references to recognized authoritative works regarding the details of domain name service. If they are not included, at trial a creative attorney can often extract nontraditional meanings from even commonly understood terms.

The next issue with an expert report is its completeness. The report must cover every item the expert wishes to opine on, and in detail. Nothing can be assumed. In some jurisdictions, if an item is not in the expert report, then the expert is not allowed to discuss it during testimony. Whether or not that is the case in your jurisdiction, it is imperative that the expert report you submit is very thorough and complete. And of course, it must be error-free. Even the smallest error can give opposing counsel an opportunity to impugn the accuracy of the entire report and the expert’s entire testimony. This is a document that should be carefully proofread by the expert and by the attorney retaining the expert.

Expert Testimony

As a forensic specialist, you will testify as an expert witness, that is, on the basis of scientific or technical knowledge you have that is relevant to a case, rather than on the basis of direct personal experience. Your testimony will be referred to as expert testimony, and there are two scenarios in which you give it: a deposition and a trial. A deposition—testimony taken from a witness or party to a case before a trial—is less formal, and is typically held in an attorney’s office. The other side’s lawyer gets to ask you questions. In fact, the lawyer can even ask some questions that would probably be disallowed by a trial judge. But do remember, this is still sworn testimony, and lying under oath is perjury, which is a felony.

U.S. Federal Rule 702, Testimony by Expert Witnesses, defines what an expert is and what expert testimony is:

A witness who is qualified as an expert by knowledge, skill, experience, training, or education may testify in the form of an opinion or otherwise if:

the expert’s scientific, technical, or other specialized knowledge will help the trier of fact to understand the evidence or to determine a fact in issue;

the testimony is based on sufficient facts or data;

the testimony is the product of reliable principles and methods; and

the expert has reliably applied the principles and methods to the facts of the case.1

This definition is very helpful. Regardless of your credentials, did you base your conclusions on sufficient facts and data? Did you apply reliable scientific principles and methods in forming your conclusions? These questions should guide your forensic work.

During a deposition, the opposing counsel has a few goals. The first goal is to find out as much as possible about your position, methods, conclusions, and even your side’s legal strategy. It is important to answer honestly but as briefly as possible. Don’t volunteer information unasked. That simply allows the other side to be better prepared for trial. The second thing a lawyer is looking for during a deposition is to get you to commit to a position you may not be able to defend later. So follow a few rules:

If you don’t fully understand the question, say so. Ask for clarification before you answer.

If you really don’t know, say so. Do not ever guess.

If you are not 100 percent certain of an answer, say so. Say “to the best of my current recollection” or something to that effect.

The other way you may testify is at trial. The first thing you absolutely must understand is that the first time you testify, you will be nervous. You’ll begin to wonder if you are properly prepared. Are your conclusions correct? Did you miss anything? Don’t worry; each time you do this, it gets easier. Next, remember that the opposing counsel, by definition, disagrees with you and wants to trip you up. It might be helpful to remind yourself, “The opposing counsel’s default position is that I am both incompetent and a liar.” Now that is a bit harsh, and probably an overstatement, but if you start from that premise you will be prepared for the opposing counsel’s questions. Don’t be too upset if he or she is trying to make you look bad. It is not personal.

The secret to deposition and trial testimony is simple: Be prepared. You should not only make certain your forensic process is done correctly and well documented, including liberal use of charts, diagrams, and other graphics, but also prepare before you testify. Go over your report and your notes again. Often, your attorney will prep you, particularly if you have never testified before. Try to look objectively at your own report to see if there is anything the opposing counsel might use against you. Are there alternative ways to interpret the evidence? If so, why did you reject them?

The most important things on the stand are to keep calm and tell the truth. Obviously, any lie, even a very minor one that is not directly related to your investigation, would be devastating. But becoming agitated or angry on the stand can also undermine your credibility.

In addition to U.S. Federal Rule 702, there are several other U.S. Federal Rules related to expert witness testimony at trial. They are listed and very briefly described here:

Rule 703, Admissibility of Facts: An expert may base an opinion on facts or data that the expert has been made aware of or personally observed. If experts in the particular field would reasonably rely on those kinds of facts or data in forming an opinion on the subject, they need not be admissible for the opinion to be admitted. But if the facts or data would otherwise be inadmissible, the proponent of the opinion may disclose them to the jury only if their probative value in helping the jury evaluate the opinion substantially outweighs their prejudicial effect.

Rule 704, Opinion on Ultimate Issue: An opinion is not objectionable just because it embraces an ultimate issue. In other words, an expert witness can, in many cases, offer an opinion as to the ultimate issue in a case.

Rule 705, Disclosing Underlying Facts for Opinion: Unless the court orders otherwise, an expert may state an opinion—and give the reasons for it—without first testifying to the underlying facts or data. But the expert may be required to disclose those facts or data on cross-examination. Essentially, the expert can state his or her opinion without first giving the underlying facts, but should expect to be questioned on those facts at some point.

Rule 706, Court-Appointed Expert: This rule covers the appointment of a neutral expert to advise the court. Such experts are not working for the plaintiff or the defendant, but rather for the court.

Rule 401, Relevance of Evidence: Evidence is relevant if: (a) it has any tendency to make a fact more or less probable than it would be without the evidence; and (b) the fact is of consequence in determining the action.