Identity Theft

Identity theft is a growing problem. It is any use of another person’s identity. Now that might seem like a pretty broad definition, but it is accurate. Most often, criminals commit identity theft in order to perpetrate some financial fraud; for example, a criminal might use the victim’s information to obtain a credit card. Then, the victim is left with the bill. The U.S. Department of Justice defines identity theft and identity fraud as:

… terms used to refer to all types of crime in which someone wrongfully obtains and uses another person’s personal data in some way that involves fraud or deception, typically for economic gain.

Notice that this definition states that it is typically for economic gain. Therefore, even unsuccessful identity theft is still a crime. The simple act of wrongfully obtaining another person’s personal data is the crime, with or without stealing any money. However, a criminal might steal someone’s identity for other reasons as well. For example, here is a real-world case. Some details have been changed to preserve confidentiality, but the essentials of the story are all true.

This crime occurred in a state that used Social Security numbers for driver’s license numbers. No state does this anymore, for good reason. In this case, an individual worked at a local office of the Department of Motor Vehicles. When someone came in to renew a license, he or she surrendered the old license. The criminal in this case took some old licenses that he thought resembled him. He then put his picture on them and used one of them if he was pulled over for a traffic ticket. This caused the ticket to be issued to the individual who owned the license, along with a ticket for having an expired license. Eventually, however, an investigation tied the tickets to his car and license plate number.

This story illustrates one way in which criminals can accomplish identity theft—by getting official documents with someone else’s information on them. It also shows an alternative reason for identity theft, one that does not involve bank accounts or credit.

This is certainly not the most common example of identity theft, but it is one possible example. Criminals also use the following common methods to perpetrate identity theft:

Phishing

Spyware

Discarded information

The following sections briefly examine each of these.

Phishing

Phishing is an attempt to trick a victim into giving up personal information. It is usually done by emailing the victim and claiming to be from some organization a victim would trust, like his or her bank or credit card company. In one of its simplest forms, a perpetrator sends out an email to a large number of people, claiming to be from some bank. The email claims that there is some issue with the recipient’s account and states the recipient needs to click a link in the email to address the problem. However, the link actually takes the recipient to a fake website that simply looks like the real website. When the victim types in his or her username and password, this fake system displays some message like “logon temporarily unavailable” or “error, please try later.” What the perpetrator has done is tricked the victim into giving the criminal the victim’s username and password for his or her bank account.

Clearly, in any mass email scenario, many recipients aren’t customers of the financial institution being faked. And those recipients will likely just delete the email. Even many of those who are customers of the spoofed financial institution won’t fall for the scam. They will delete the email, too. But, in this case, it is a numbers game for the criminal. If he or she sends out enough of these emails, it is certain that someone will fall for it. So the trick is to send out as many emails as possible, and know that only a small percentage will respond.

Phishing is generally a process of reaching out to as many people as possible, hoping enough people respond. In general, about as many people fall for scam emails as respond to other, legitimate, unsolicited bulk emails, or spam. A good fictitious email gets a 1–3 percent response rate, according to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). An identity thief—if he or she uses the target organization’s format, spells everything correctly, and uses logos and artwork that look legitimate—can count on a response of 10,000 to 30,000 click throughs per million emails sent.

Recent years have seen the growth of more targeted attacks. One type of targeted attack is called spear phishing. With spear phishing, the criminal targets a specific group; for example, the criminal may want to get information about the network of a specific bank, so he or she targets emails to the IT staff at that bank. The emails are a bit more specific, and thus more likely to look legitimate to the recipients.

Similar to spear phishing is whaling. This is phishing with a specific, high-value target in mind. For example, the attacker may target the CIO of a bank. First, the attacker performs a web search on that CIO and learns as much about him or her as possible. LinkedIn, Facebook, and other social media can be very helpful in this regard. Then, the attacker sends an email targeted to that specific individual. This makes it much more likely the email will appear legitimate and the victim will respond.

One scenario is to research the target, the CIO in this case, and find out his or her hobbies. For example, if the CIO is an avid fisherman, the attacker might send him or her an email offering a free subscription to a fishing magazine if he or she fills out a survey. The survey is generic, but requires the target to select a password. This is important because most people reuse passwords. Whatever password the CIO selects, it is likely he or she used that same password elsewhere as well. Even if it is not used as his or her network logon password, it could be a password to a Hotmail, Gmail, LinkedIn, or Facebook account. This gives the attacker an inroad into that person’s electronic life. From there, it is a matter of time before the attacker is able to secure the victim’s network credentials.

Information learned in phishing can also be used in social engineering or other highly targeted attacks such as advanced persistent threat attacks, which are ongoing attacks that make repeated and concerted attempts at phishing. This type of attack is usually conducted for a specific, high-value target.

Spyware

Spyware is any software that can monitor your activity on a computer. It may involve taking screenshots or perhaps logging keystrokes. It can even be as simple as a cookie that simply records a few brief facts about your visit to a website. Normal web traffic is “stateless,” meaning no information is passed from page to page without help. One way this can be accomplished is via cookies. For example, when you visit Amazon.com, the site remembers what you were last searching for, because that information gets written to a tiny text file. Now some people might object to website cookies being labeled as spyware. And it should be pointed out that cookies have many legitimate uses. However, it is up to whoever programmed the website to decide what information is stored in a website cookie and how it will be used. This means that, at least technically speaking, cookies could be considered spyware.

It has been claimed that 80 percent of all computers connected to the Internet have spy-ware. Whether the number is really that high is hard to determine. However, it is a fact that spyware is quite prevalent. One reason is that the software itself is perfectly legal, if used correctly. There are two situations that allow a person to legally monitor another person’s computer usage. The first is parents monitoring minor children. If a child is under the age of 18, it is perfectly legal for the parents to monitor their child’s computer activity. In fact, some experts would go so far as to say it is neglectful not to monitor a young child on the Internet. Another legal application of computer monitoring is in the workplace. Numerous court cases have upheld an employer’s right to monitor computer and Internet usage on company-owned equipment.

Because there are legal applications of “spying” on a person’s computer usage, a number of spyware products are easily and cheaply available. Just a few are listed here:

Teen Safe: This product can be found at http://www.teensafe.com.

Web Watcher: This product can be found at https://www.webwatcher.com.

ICU: This product can be found at http://www.softpedia.com/get/Security/Security-Related/ICU-Child-Monitoring-Software.shtml.

WorkTime: This product can be found at http://www.nestersoft.com/worktime/corporate/employee_monitoring.shtml.

The only issue for a criminal who wants to misuse this software is how to get it on the target system. In some cases, it is done via a Trojan horse. The victims are tricked into downloading the spyware onto their machines. In other cases, the spyware can be distributed like a virus, infecting various machines. It is also possible to manually put spyware on a machine. This is usually done when the spyware is being placed due to a warrant for a law enforcement agency to monitor a target system, or when a private citizen is legally placing spyware on a system.

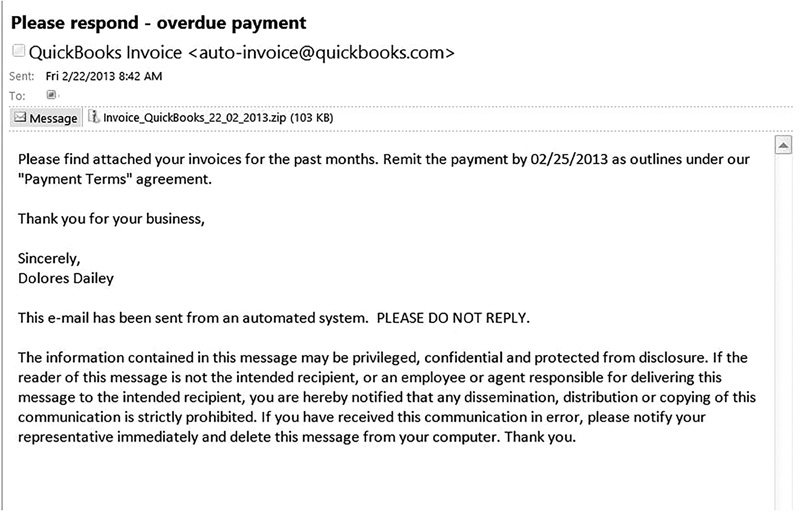

Of course, spyware can also be placed on the target’s machine by tricking the user into opening an attachment. You may get several emails every week that try to lure you into opening some attachment. These have either a virus, spyware, or a Trojan horse. You can see one example of such an email in FIGURE 2-1.

The email entices the user into clicking on the attachment and downloading it. At that point, some sort of malware is installed on the user’s machine.

After the software is installed on the victim’s computer, it begins to gather information about that person’s Internet and computer activities. For criminals, the most interesting information is usually financial data, bank logons, and so forth.

FIGURE 2-1

An email attachment.

Used with permission from Microsoft.

Discarded Information

Another method that allows a hacker to gather information about a person’s identity is discarded information. Any documents that are thrown out without first being shredded could potentially aid an identity thief. This usually doesn’t leave much forensic evidence, but it does indicate that the perpetrator is local in order to access the victim’s trash, a practice commonly known as dumpster diving.

How Does This Crime Affect Forensics?

If the crime being investigated is identity theft, then the first thing the investigator should be looking for is spyware on the victim’s machine. It is very likely that somewhere on the victim’s machine is some type of spyware. If spyware exists, the investigator must start searching for where the spyware is sending its data. Yes, spyware collects data on the user’s computer and Internet activities, but ultimately that data must be communicated to the criminal. It could be something as simple as a periodic email with an attachment. Or it could be a stream of packets to a server the criminal has access to. Whatever the specific communication mechanism, there absolutely must be some way to get the information from the victim’s computer to the attacker—and that will leave some forensic trace.

Another issue the investigator should explore is that of phishing emails. It is important to check the email history for the victim’s computer as well as the web history. If a phishing website was involved, it is important to gather information about that site.