Non-Access Computer Crimes

Non-access computer crimes are crimes that do not involve an attempt to actually access the target. For example, a virus or logic bomb does not require the attacker to attempt to hack into the target network. And denial of service attacks are designed to render the target unreachable by legitimate users, not to provide the attacker access to the site.

Denial of Service

A denial of service (DoS) attack is an attempt to prevent legitimate users from being able to access a given computer resource. The most common target is a website. Although there are a number of methods for executing this type of attack, they all come down to the simple fact that every technology can handle only a finite load. If you overload the capacity of a given technology, it ceases to function properly. If you flood a website with fake connections, it becomes overloaded and unable to respond to legitimate connection attempts. This is a classic example of a denial of service attack. Although these attacks may not directly compromise data or seek to steal personal information, they can certainly cause serious economic damages. Imagine the cost incurred if a denial of service attack were to take eBay offline for a period of time!

Denial of service attacks are the cyber equivalent of vandalism. Rather than seek to break into the target system, the perpetrator simply wants to render the target system unusable. These attacks require minimal skill. For example, consider one of the most basic DoS attacks, called a SYN flood. This simple attack takes advantage of how connections to websites are established. So, first, let’s take a look at how that works.

The client machine sends a Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) packet to the server with a synchronize flag turned on—it is a single bit that is turned to a 1. Because this is synchronizing, or starting the connection, it is called a SYN flag.

The server sets aside enough resources to handle the connection and sends back a TCP packet with two flags turned on: the acknowledgment flag (ACK) and the synchronize (SYN) flag. Essentially, this is acknowledging the request to synchronize. The client is supposed to respond with a single ACK flag to establish the connection and allow communications to begin. This is called the three-way handshake.

In the SYN flood attack, the attacker keeps sending SYN packets but never responds to the SYN/ACK packets it receives from the server. Eventually, the server has opened up a number of connections for a client that never fully connects and can no longer respond to legitimate users.

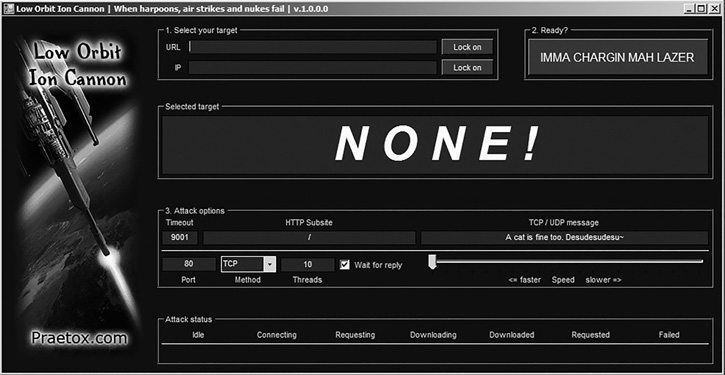

In addition to various DoS attack types, there are tools that can be used to create a denial of service attack. One of the most easy to use is the Low Orbit Ion Cannon, shown in FIGURE 2-3. This tool is freely available on the Internet and terribly easy to use. The prevalence of such easy-to-use tools is one reason why denial of service attacks are so common.

The Tribe Flood Network (TFN) is probably the most widely used distributed denial of service tool. There is a newer version of it called TFN2K. The new version sends decoy information to make tracing more difficult. Both the original and new version work by configuring the software to attack a particular target, and then getting the target on a specific machine. Usually, the attacker seeks to infect several machines with the TFN program in order to form a Tribe Flood Network. Instead of connection requests originating from one machine, the barrage is distributed across many. This attack variation is called a distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack.

You can get more details about TFN and TFN2K at these websites:

Washington University at http://staff.washington.edu/dittrich/misc/tfn.analysis.txt

Packet Storm Security at http://packetstormsecurity.com/distributed/TFN2k_Analysis-1.3.txt

FIGURE 2-3

Low Orbit Ion Cannon.

Courtesy of Praetox Technologies

The Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT) at http://www.cert.org/advisories/CA-1999-17.html

Trin00 is another popular DoS tool. It was originally available only for UNIX but is now available for Windows as well. It is an alternative to TFN. One common technique attackers use is to send the Trin00 client to machines via a Trojan horse. Then, the infected machines can all be used to launch a coordinated attack on the target system.

Another type of DoS attack that has become more prevalent in recent years is the telephony denial of service (TDoS) attack. A TDoS attack is possible, and certainly has been documented, with traditional telephone systems by using an automatic dialer to tie up target phone lines. TDoS is flourishing, however, with the wide availability of Voice over IP (VoIP) tools that make automated TDoS attacks against traditional and IP-based VoIP very easy to carry out. The way that a TDoS attack works is that a call center or business receives so many inbound calls that the equipment and staff are overwhelmed and unable to do business. A call to a supervisor or manager then demands a certain amount of money be sent or a certain eradication service be purchased to stop the attacks.

How Does This Crime Affect Forensics?

When investigating denial of service attacks launched from a single machine, the obvious task is to trace the packets coming from that machine. It is common for attackers to spoof some other IP address, but not as common for them to spoof a MAC address, which is related to the underlying hardware. If the attacker is not savvy enough to spoof the MAC address, then each packet contains evidence of the actual machine that it was launched from.

In distributed denial of service attacks, the packets come from a multitude of machines. Usually, the owners of these machines are unaware that their machines are being used in this way. However, that does not mean the investigation is at a dead end. You can still trace back the packets and get a group of infected machines. You can then seek out commonalities on those machines. Did they all download the same free game from the Internet or frequent the same website? Anything that all infected machines have in common is a candidate for where the machines got the software that launched the distributed denial of service attack.

Viruses

Viruses are a major problem in modern computer systems. A virus is any software that self-replicates, like a human or animal virus. It is common for viruses to also wreak havoc on infected machines, but the self-replication is the defining characteristic of a virus. Before discussing the forensics of viruses, it is a good idea to consider some recent viruses:

FakeAV.86: This is a fake antivirus. It purports to be a free antivirus scanner, but is really itself a Trojan. This virus first appeared in July 2012. It affected Windows systems ranging from Windows 95 to Windows 7 and Windows Server 2003. This is not the only fake anti-virus to have been found, but it is a widespread one.

Flame: No modern discussion of viruses would be complete without a discussion of Flame, a virus that targeted Windows operating systems. The first item that makes this virus notable is that it was specifically designed for espionage. It was first discovered in May 2012 at several locations, including Iranian government sites. Flame is spyware that can monitor network traffic and take screenshots of the infected system. This malware stores data in a local database that is heavily encrypted. Flame is also able to change its behavior based on the specific antivirus running on the target machine. This indicates that this malware is highly sophisticated. Also of note is that Flame is signed with a fraudulent Microsoft certificate. This means that Windows systems would trust the software.

These two pieces of malware give you some idea of the impact a virus can have on an organization’s network. Viruses range from terribly annoying, like FakeAV, to sophisticated mechanisms for espionage, like Flame. A few other more recent viruses are listed briefly here:

Gameover ZeuS is a virus that creates a peer-to-peer botnet. This virus first began to spread in 2015. The virus creates encrypted communication between infected computers and the command and control computer, allowing the attacker to control the various infected computers.

The Rombertik virus began to be seen in 2015. This virus uses the browser to read user credentials to websites. It is most often sent as an attachment to an email. The virus can also either overwrite the master boot record on the hard drive, making the machine unbootable, or begin encrypting files in the user’s home directory.

In 2016 the Locky virus began to show up. It is a ransomware virus that encrypts sensitive files on the victim computer and then demands ransom for the encryption key. Unlike previous ransomware viruses, this one can encrypt data on unmapped network shares.

Viruses can be divided into distinct categories. A list of major virus categories is provided here:

Macro: Macro viruses infect the macros in office documents. Many office products, including Microsoft Office, allow users to write mini-programs called macros. These macros can also be written as a virus. This type of virus is very common due to the ease of writing such a virus.

Memory resident: A memory-resident virus installs itself and then remains in RAM from the time the computer is booted up until it is shut down.

Multipartite: Multipartite viruses attack the computer in multiple ways, for example, infecting the boot sector of the hard disk and one or more files.

Armored: An armored virus uses techniques that make it hard to analyze. This is done by either compressing the code or encrypting it with a weak encryption method.

Sparse infector: A sparse infector virus attempts to elude detection by performing its malicious activities only sporadically. With a sparse infector virus, the user will see symptoms for a short period, then no symptoms for a time. In some cases the sparse infector targets a specific program but the virus only executes every 10th time or 20th time that target program runs.

Polymorphic: A polymorphic virus literally changes its form from time to time to avoid detection by antivirus software. A more advanced form of this is called a metamorphic virus; it can completely rewrite itself.

How Does This Crime Affect Forensics?

Viruses are remarkably easy to locate, but difficult to trace back to the creator. The first step is to document the particulars of the virus—for example, its behavior, the file characteristics, and so on. Then, you must see if there is some commonality among infected computers. For example, if all infected computers visited the same website, then it is likely that the website itself is infected. In addition, numerous sources of information about known viruses are available on the Internet from software publishers and virus researchers, which is very useful in doing forensic research.

It is a slow and tedious process, but it is possible to track down the creator of a virus.

Logic Bombs

A logic bomb is malware designed to harm the system when some logical condition is reached. Often it is triggered based on a specific date and time. It is certainly possible to distribute a logic bomb via a Trojan horse, but this sort of attack is often perpetrated by employees. The following two cases illustrate this fact:

In June 1992, Michael Lauffenburger, an employee of defense contractor General Dynamics, was arrested for inserting a logic bomb that would delete vital rocket project data. Another employee of General Dynamics found the bomb before it was triggered. Lauffenburger was charged with computer tampering and attempted fraud and faced potential fines of $500,000 and jail time, but was actually fined only $5000.

In June 2006, Roger Duronio, a system administrator for the Swiss bank UBS, was charged with using a logic bomb to damage the company’s computer network. His plan was to drive the company stock down due to damage from the logic bomb; thus, he was charged with securities fraud. Duronio was later convicted and sentenced to 8 years and 1 month in prison, as well as $3.1 million in restitution to UBS.

How Does This Crime Affect Forensics?

Logic bombs that are created by disgruntled employees are actually reasonably straightforward to investigate. First, the nature of the logic bomb gives some indication of the creator. It has to be someone with access to the system and with a programming background. Then, traditional issues such as motive are also helpful in investigating a logic bomb. If the logic bomb is distributed randomly via a Trojan horse, then investigating it follows the same parameters as investigating a virus.