Common Forensic Software Programs

After setting up the lab and the equipment, the next thing to address is the software. Several software tools are available that you might want to use in your forensic lab. This section takes a brief look at several commonly used tools. However, this section gives extra attention to Guidance Software’s EnCase and AccessData’s Forensic Toolkit because these two programs are very commonly used by law enforcement.

EnCase

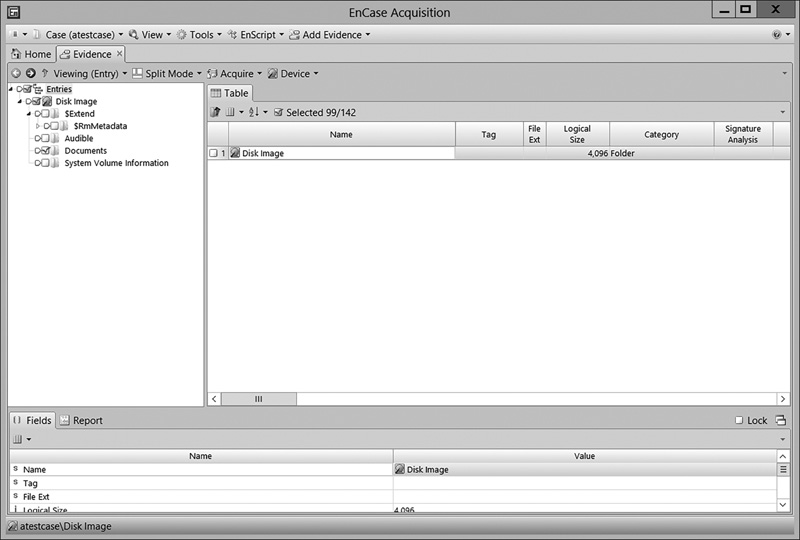

EnCase from Guidance Software is a very widely used forensic toolkit. This tool allows the examiner to connect an Ethernet cable or null modem cable to a suspect machine and to view the data on that machine. EnCase prevents the examiner from making any accidental changes to the suspect machine. This is important: Remember the basic principle of touching the suspect machine as little as possible. EnCase organizes information into “cases.” This matches the way examiners normally examine computers.FIGURE 3-1 shows a sample case.

FIGURE 3-1

EnCase case file.

Courtesy of Guidance Software, Inc.

The EnCase concept is based on the evidence file. This file contains the header, the checksum, and the data blocks. The data blocks are the actual data copied from the suspect machine, and the checksum is done to ensure there is no error in the copying of that data and that the information is not subsequently modified. Any subsequent modification causes the new checksum not to match the original checksum. As soon as the evidence file is added to the case, EnCase begins to verify the integrity of the entire disk image. The evidence file is an exact copy of the hard drive. EnCase calculates an MD5 hash when the drive is acquired. This hash is used to check for changes, alterations, or errors. When the investigator adds the evidence file to the case, it recalculates the hash; this shows that nothing has changed since the drive was acquired.

You can use multiple methods to acquire the data from the suspect computer:

EnCase boot disk: This method boots the system to EnCase using DOS mode rather than a GUI mode. You can then copy the suspect drive to a new drive to examine it.

EnCase network boot disk: This is very similar to the EnCase boot disk, but it allows you to perform the process over a crossover cable between the investigator’s computer and the computer being investigated.

LinEn boot disk: This is specifically for acquiring the contents of a Linux machine. It operates much like the boot disk method, but is for target machines that are running Linux.

After you have acquired a suspect drive, you can then examine it using EnCase.

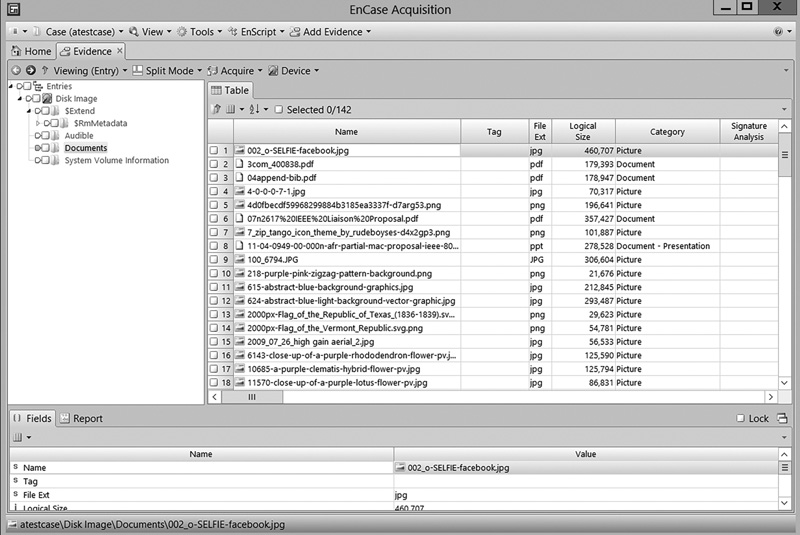

The EnCase Tree pane is like Windows Explorer. It lists all the folders and can expand any particular element in the tree (folders or subfolders). The Table pane lists the subfolders and files contained within the folder that was selected in the Tree pane. When you select an item, it is displayed in the View pane, as shown in FIGURE 3-2.

The Filter pane is a useful tool that can affect the data you view in the Table pane.

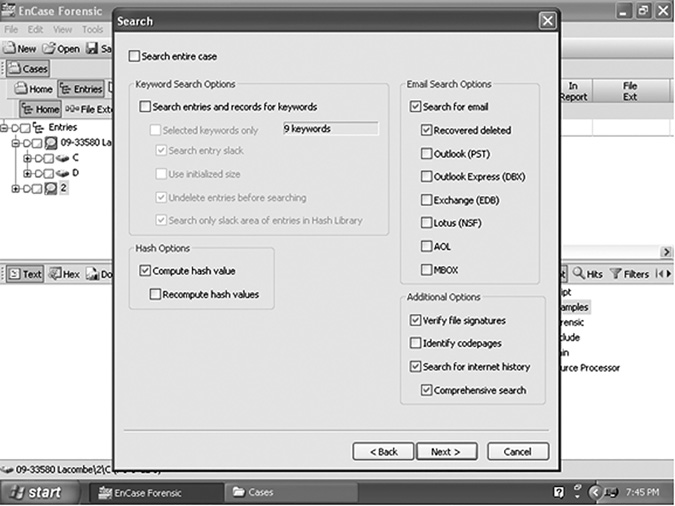

It allows you to filter what you view, narrowing your focus to specific items of interest. You can also search data using the EnCase Search feature, shown in FIGURE 3-3.

This is just a very brief introduction to EnCase. It is a very popular tool with law enforcement, and the vendor, Guidance Software, offers training for its product. You can visit the vendor website for more details at http://www.guidancesoftware.com.

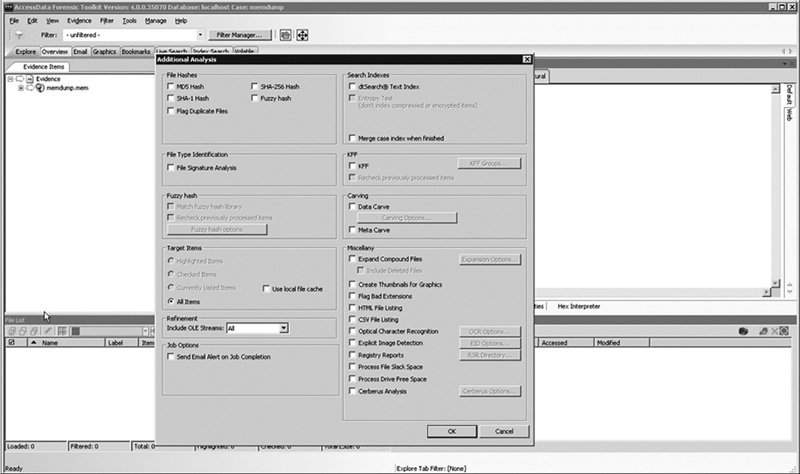

Forensic Toolkit

The Forensic Toolkit (FTK) from AccessData is another widely used forensic analysis tool that is also very popular with law enforcement. You can get additional details at the company’s website, http://accessdata.com/product-download/digital-forensics, but this section reviews some basics of the tool. With FTK, you can select which hash to use to verify the drive when you copy it, which features you want to use on the suspect drive, and how to search, as shown in FIGURE 3-4.

Forensic Toolkit is particularly useful at cracking passwords. For example, password-protected Portable Document Format (PDF) files, Excel spreadsheets, and other documents often contain important information. FTK also provides tools to search and analyze the Windows Registry. The Windows Registry is where Windows stores all information regarding any programs installed. This includes viruses, worms, Trojan horses, hidden programs, and spyware. The ability to effectively and efficiently scan the Registry for evidence is critical.

FIGURE 3-2

EnCase View pane.

Courtesy of Guidance Software, Inc.

FIGURE 3-3

EnCase Search.

Courtesy of Guidance Software, Inc.

FIGURE 3-4

FTK features.

Courtesy of AccessData Group, Inc.

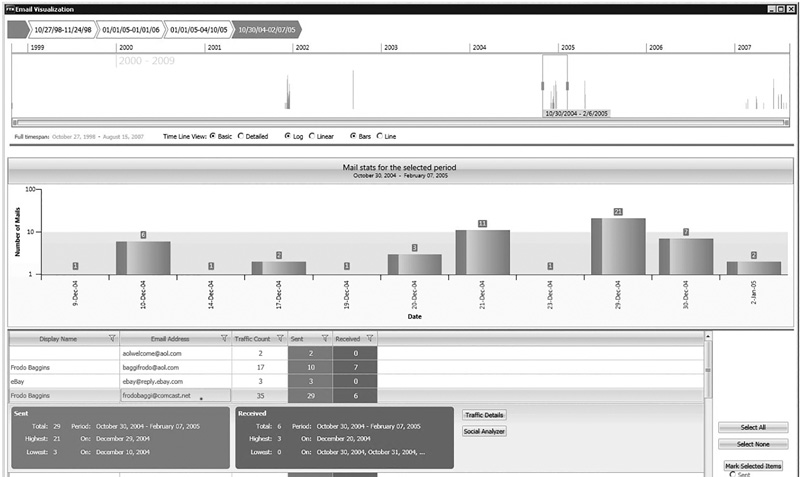

FTK gives you a robust set of tools for examining email. The email can be arranged in a timeline, giving the investigator a complete view of the entire email conversation and the ability to focus on any specific item of interest, as shown in FIGURE 3-5.

Another feature of this toolkit is its distributed processing. Scanning an entire hard drive, searching the Registry, and doing a complete forensic analysis of a computer can be a very time-intensive task. With AccessData’s Forensic Toolkit, processing and analysis can be distributed across up to three computers. This lets all three computers perform the three parts of the analysis in parallel, thus significantly speeding up the forensic process. In addition, FTK has an Explicit Image Detection add-on that automatically detects pornographic images. This is very useful in cases involving allegations of pornography. This is a particularly useful tool for law enforcement. FTK is available for Windows or Macintosh.

OSForensics

This tool has been widely used since about 2010. It is from the company Passmark software in Australia. One of the first attractive aspects of this tool is its cost. The full product is $899. This is a fraction of the cost of many other tools. There is also a fully functional 30-day trial version. Furthermore, it is very easy to use. It will do most of what Encase and FTK will do, but lacks a few of those products’ specialized features. For example, OSForensics does not have a Known File Filter, as does FTK.

FIGURE 3-5

Email analysis.

Courtesy of AccessData Group, Inc.

Helix

Helix is a customized Linux Live CD used for computer forensics. The suspect system is booted into Linux using the Helix CDs, and then the tools provided with Helix are used to perform the analysis. This product is robust and full of features, but simply has not become as popular as AccessData’s FTK and Guidance Software’s EnCase. For more information, check out the company’s website at http://www.e-fense.com/products.php.

Kali Linux

Kali Linux (formerly called BackTrack) is a Linux Live CD that you use to boot a system and then use the tools. Kali is a free Linux distribution, making it extremely attractive to schools teaching forensics or to laboratories on a strict budget. It is not used just for forensics, however; it offers a wide array of general security and hacking tools. In fact, it is probably the most widely used collection of security tools available.

AnaDisk Disk Analysis Tool

AnaDisk, from New Technologies Incorporated (NTI), turns a PC into a sophisticated disk analysis tool. The software was originally created to meet the needs of the U.S. Treasury Department in 1991. AnaDisk scans for anomalies that identify odd formats, extra tracks, and extra sectors. It can be used to uncover sophisticated data-hiding techniques.

AnaDisk supports all DOS formats and many non-DOS formats, such as Apple Macintosh and UNIX TAR. If a disk will fit in a PC CD drive, it is likely that AnaDisk can be used to analyze it. For information on AnaDisk, see http://www.retrocomputing.org/cgi-bin/sitewise.pl?act=det&p=776&id=retroorg.

CopyQM Plus Disk Duplication Software

CopyQM Plus from NTI essentially turns a PC into a disk duplicator. In a single pass, it formats, copies, and verifies a disk. This capability is useful for system forensics specialists who need to preconfigure CDs for specific uses and duplicate them. In addition, CopyQM Plus can create self-extracting executable programs that can be used to duplicate specific disks. CopyQM is an ideal tool for use in security reviews because once a CopyQM disk creation program has been created, anyone can use it to make preconfigured security risk assessment disks. When the resulting program is run, the disk image of the original disk is restored on multiple disks automatically. The disk images can also be password-protected when they are converted to self-extracting programs. This is helpful when security is a concern, such as when disks are shared over the Internet. CopyQM Plus is particularly helpful in creating computer incident response toolkit disks.

CopyQM Plus supports all DOS formats and many non-DOS formats, such as Apple Macintosh and UNIX TAR. It copies files, file slack, and unallocated storage space. However, it does not copy all areas of copy-protected disks—extra sectors added to one or more tracks on a CD. AnaDisk software should be used for this purpose. For information on CopyQM Plus, see http://vetusware.com/download/CopyQM%203.24/?id=6457.

The Sleuth Kit

The Sleuth Kit is a collection of command-line tools that are available as a free download. You can get them from this site: http://www.sleuthkit.org/sleuthkit/. This toolset is not as rich or as easy to use as EnCase, FTK, or OSForensics, but it can be a good option for a budget-conscious agency. The most obvious of the utilities included is ffind.exe.

There are options to search for a given file or to search for only deleted versions of a file. This particular utility is best used when you know the specific file you are searching for. It is not a good option for a general search. A number of utilities are available in Sleuth Kit; however, many people find using command-line utilities to be cumbersome. Fortunately, a graphical user interface (GUI) has been created for Sleuth Kit. That GUI is named Autopsy and is available at http://www.sleuthkit.org/autopsy/download.php.

Disk Investigator

This is a free utility that comes as a graphical user interface for use with Windows operating systems. You can download it from http://www.theabsolute.net/sware/dskinv.html. It is not a full-featured product like EnCase, but it is remarkably easy to use. When you first launch the utility, it presents you with a cluster-by-cluster view of your hard drive in hexadecimal form.

From the View menu, you can view directories or the root. The Tools menu allows you to search for a specific file or to recover deleted files.

Entire books could be written about the various forensic utilities available on the Internet. It is a good idea for any investigator to spend some time searching the Internet and experimenting with various utilities. Depending on your own skill set, technical background, and preferences, you might find one utility more suitable than another. It is also recommended that after you select a tool to use, you scan the Internet for articles about that tool. Make certain that it has widespread acceptance and that there are no known issues with its use. It can also be useful to use more than one tool to search a hard drive. If multiple tools yield the same result, this can preempt any objections the opposing attorney or his or her expert may attempt to present at trial. And remember—as always—to document every single step of your investigation process.