An HBase cluster is divided into namespaces. A namespace is a logical collection of tables, representing an application or organizational unit.

A table in HBase is made up of rows and columns, like a table in any other database. The table is divided up into regions such that each region is a collection of rows. A row cannot be split across regions:

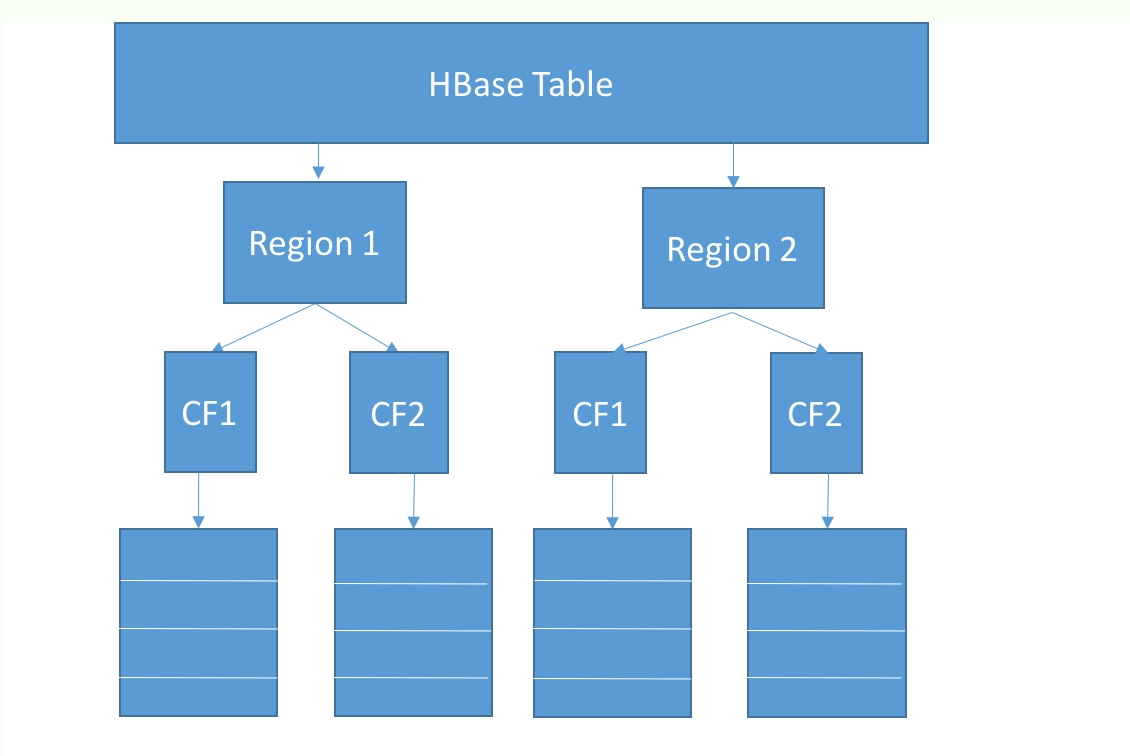

However, in addition to rows and columns, HBase has another construct called a ColumnFamily. A ColumnFamily, as the name suggests, represents a set of columns. For a given set of rows, all data for columns in a column family is stored physically together on a disk. So, if a table has a single region with 100 rows and two column families with 10 columns each, then there are two underlying HFiles, corresponding to each column family.

What should the criteria be for grouping columns within a column family? Columns that are frequently queried together can be grouped together to achieve locality of reference and minimize disk seeks. Within a column family are a collection of columns that HBase calls column qualifiers. The intersection of every row plus column family plus column qualifier is called an HBase cell and represents a unit of storage.

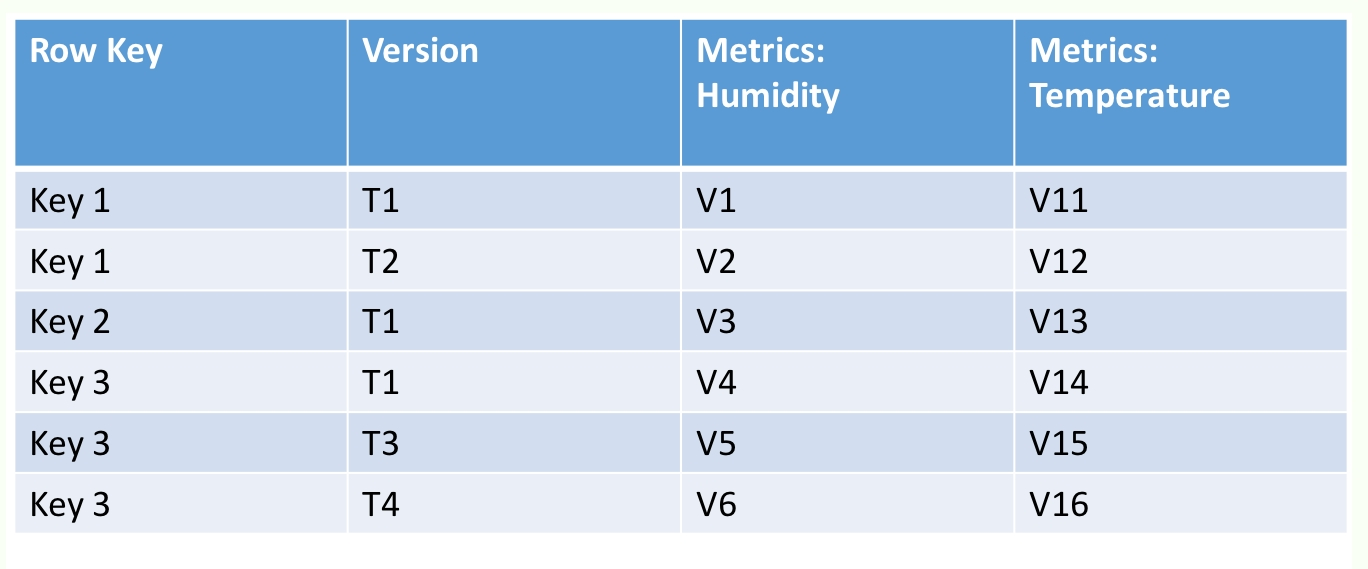

Within an HBase cell, rather than storing a single value, HBase stores a time series of edits to the cell. Each update is associated with the timestamp of when the update was made. HBase allows you to provide a timestamp filter in the read requests, thus enabling you to not just read the latest value in a cell, but the value of the cell as of a point in time. Each row in HBase is identified by a row key. The row key, like the value in the cells, is stored as an array of bytes:

How do all these logical entities map to a physical representation on a disk? A detailed description of the HFile structure is outside the scope of the book, but we'll discuss it at a high level here.

HBase sorts data on the row key (lexicographic byte ordering). Within the row, data is sorted by the column name. Within each cell, data is sorted in reverse order of the timestamp. This ordering allows HBase to quickly triangulate a specific cell version.

HBase stores the row key along with each cell, instead of once per row. This means that if you have a large number of columns and a long row key, there might be some storage overhead. HBase allows for data in tables to be compressed via multiple codecs, snappy, gzip, and lzo. Typically, snappy compression helps achieve a happy medium between the size of the compressed object and the compression/decompression speeds.

HBase also supports a variety of data block encoding formats, such as prefix, diff, and fast diff. Often, column names have repeating elements, such as timestamps. The data block encoders help reduce the key storage overhead by exploiting commonalities in the column names and storing just the diffs.

As discussed before, HFiles also contain a multilevel index. Top-level index blocks are loaded from the HFiles and pinned in the RegionServer memory. And as discussed, HFiles also contain probabilistic data structures ("bloom filters"), allowing for entire HFiles to be skipped if the bloom filter probe turned up empty.

Data is stored as a byte array within an HBase cell. There are no data types in HBase, so the bytes within an HBase cell might represent a string, an int, or a date. HBase doesn't care. It's left to the application developer to remember how a value was encoded and decode it appropriately.

HBase itself is schemaless. This not only means that there is no native type system, it means that there is no well-defined structure for each row. This means that when you create a table in HBase, you only need to specify what the column family is. The column qualifiers aren't captured in the table schema. This makes it a great fit for sparse, semi-structured data since each row only needs to allocate storage for the columns that will be contained within it.

So how does someone store data in HBase if there are so many degrees of freedom in terms of how the data is modeled? Often, novice HBase users make assumptions about expected performance based on a theoretical understanding of its internal workings. However, they are often surprised when the actual footprint is different from their back-of-an-envelope calculations, or when latencies are worse than they expected. The only scientific approach here is to do a quantitative evaluation of schemas and understand the storage footprint and the latencies for reading and writing data at scale.