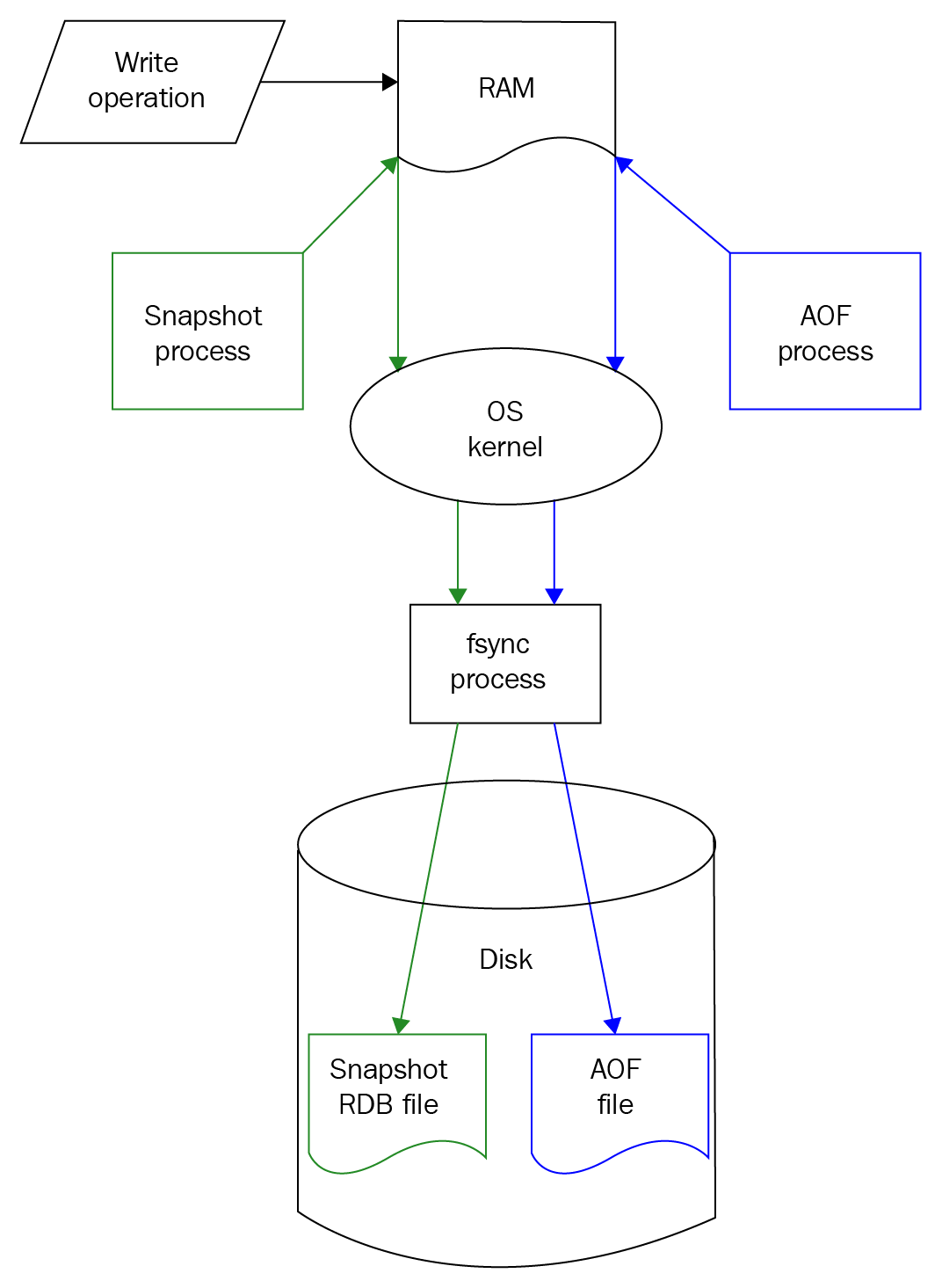

The underlying architecture that allows Redis to perform so well is that data is both stored and read from RAM. The contents of RAM can be persisted to disk with two different options:

- Via a forked snapshot process which creates an RDB file

- Using Append-only Files (AOF), which saves each write individually

While using the AOF option has a direct impact on performance, it is a trade-off that can be made depending on the use case and the amount of data durability that an application requires. Redis allows you to use either AOF, snapshots, or both. Using both is the recommended approach, and the two features are designed so as not to interfere with each other.

Snapshots produce RDB files, providing an option for point-in-time recovery. They are written based on the number of keys updated over a specified amount of time. By default, Redis writes snapshots under the following conditions:

- Every 15 minutes, assuming that at least one key has been updated

- Every 5 minutes, assuming that at least 10 keys have been updated

- Every minute, assuming that at least 10,000 keys have been updated

With AOF, each write operation to Redis is logged and written immediately. The problem with the immediate write is that it has simply been written to the kernel's output buffer, and not actually written to disk.[11] Writing the contents from the output buffers to disk happens only on a (POSIX) fsync call. With RDB snapshots representing a point-in-time of Redis' data, the 30 seconds to wait for fsync isn't as much of a concern. But for AOF, that 30 seconds could equate to 30 seconds of unrecoverable writes. To control this behavior, you can modify the appendfsync setting in the configuration file to one of three options:

- always: This calls fsync with every write operation, forcing the kernel to write to disk

- everysec: This calls fsync once per second to invoke a write to disk

- no: This lets the operating system decide when to call fsync; it is usually within 30 seconds

A graphical representation of this functionality can be seen in the following figure:

Obviously, the less Redis has to block for disk I/O, the faster it will be. Always calling fsync will be slow. Letting the operating system decide may not provide an acceptable level of durability. Forcing fsync once per second may be an acceptable middle ground.

Also, fsync simply forces data from the OS cache to the drive controller, which may also (read: probably does) use a cache. So our writes are not even committed at that point. Even Sanfilippo illustrates how hard it is to be sure of your data durability at this point when he later states:[11]