The popularity and ubiquity of responsive web design makes it an easier sell to clients and stakeholders than ever before. Most people have some idea what responsive web design is about. The notion of a single codebase that will just work across all devices is a compelling offering.

One question that almost always comes up when starting a responsive design project is that of browser support. With so many browser and device variants, it's not always pragmatic to support every single browser permutation fully. Perhaps time is a limiting factor, perhaps money. Perhaps both.

Typically, the older the browser, the greater the work and code required to gain feature or aesthetic parity with modern browsers. Therefore, it may make more sense to have a leaner, and therefore faster, codebase by tiering the experience and only providing enhanced visuals and capabilities for more capable browsers.

In the previous edition of this book, some time was spent covering how to cater for very old desktop-only browsers. In this edition, we will not.

As I write this in mid-2015, Internet Explorer 6, 7, and 8 are all but gone. Even IE 9 only has a 2.45% worldwide share of the browser market (IE 10 is only 1.94% while IE 11 is rising nicely at 11.68%). If you have no alternative but to develop for Internet Explorer 8 and below, you have my sympathies and I'm afraid I must be upfront and advise you that there won't be a terrific amount you can use in this book.

For everyone else, you owe it to your client/paymaster to explain why developing for ailing browsers might be a mistake and investing development time and resource primarily for modern browsers and platforms makes good fiscal sense in every respect.

Ultimately however, the only statistics that really matter are yours. In all but extreme cases, the sites we build should at least be functional in every common browser. Beyond basic functionality, for any web project it makes sense to decide, in advance, what platforms you want to fully enhance the experience for, and which you are happy to concede visual/functional anomalies to.

You'll also find that practically, starting with the simplest 'base level' experience and enhancing (an approach known as progressive enhancement) is easier than coming at the problem from the opposite direction—building the ultimate experience first then attempting to provide fall backs for less capable platforms (an approach known as graceful degradation).

To exemplify why knowing this in advance matters, consider that if you were unlucky enough to have 25% of your website visitors using Internet Explorer 9 (for example), you'd need to consider what features that browser supports and tailor your solution accordingly. The same caution would be required if large amounts of your users are visiting with older mobile phone platforms such as Android 2. What you can consider a 'base' experience will vary depending upon the project.

If suitable data isn't available, I apply a simple and crude piece of logic to determine whether I should spend time developing a particular platform/browser version: if the cost of developing and supporting browser X is more than the revenue/benefit created by the users on browser X; don't develop specific solutions for browser X.

It's rarely a question of whether you could 'fix' an older platform/version. It's a question of whether you should.

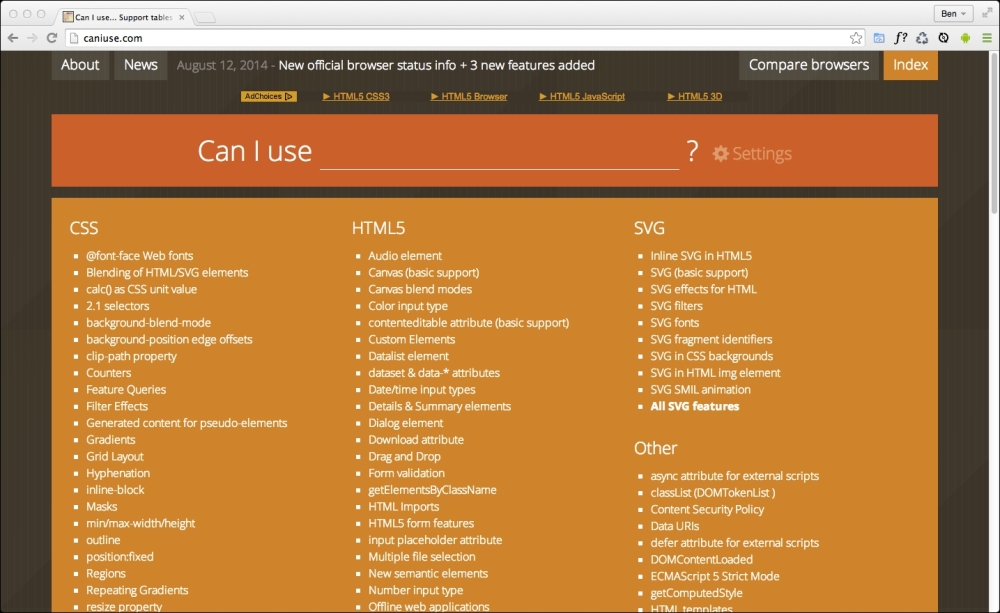

When considering which platforms and browser versions support which features, if you aren't already, become familiar the http://caniuse.com website. It provides a simple interface for establishing what browser support there is for the features we will be looking at throughout.

It makes no difference what text editor or IDE system you use to build your responsive web designs. If the simplest of text editors allows you to write your HTML, CSS, and JavaScript efficiently, that's absolutely fine. Similarly there are no requisite pieces of tooling that are essential to get a responsive web design out of the door. All you actually need is something that enables you to write HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. Whether your preference is Sublime Text, Vim, Coda, Visual Studio, or Notepad - it matters little. Just use what works best for you.

However, be aware that there are more tools available now (often free) to negate many of the manual and time-intensive tasks of building web sites than ever before. For example, CSS processors (Sass, LESS, Stylus, PostCSS) can help with code organization, variables, color manipulations, and arithmetic. Tools like PostCSS can also automate horrible and thankless jobs like CSS vendor prefixing. Furthermore, 'Linting' and validation tools can check your HTML, JavaScript, and CSS code against standards as you work, eliminating many time wasting typos or syntax errors.

New tools come out constantly and they are continually improving. Therefore, whilst some relevant and beneficial tools will be mentioned by name as we go, be aware that something better may be just around the corner. Hence we won't be relying on anything other than standards based HTML and CSS in our examples. You should however, use whatever tools you can to produce your front-end code as quickly and reliably as possible.