Web Storage

Recording information about previous activity is usually done with cookies, but one of their drawbacks is that you can store only small amounts of data. The Web Storage API was created to allow user agents to store more data on the user’s device. This data can be stored only until the browser is closed, which is known as session storage, or kept until the user or another script actively flushes the data, which is called local storage. Both operate in essentially the same way, except for that one key difference—permanence.

To store data, you save it in key:value pairs, similar to how you store cookies now, except the quantity of data that can be saved is greater. The API has two key objects, which are straightforward and memorable: localStorage for local storage and sessionStorage for session storage.

Note

In the examples in this section I use sessionStorage, but you can swap this for localStorage if you prefer more permanent storage; the syntax applies equally.

The web storage syntax is pretty flexible, allowing three different ways to store an item: with the setItem() method, with square bracket notation, or with dot notation. As a simple example, the next code snippet shows how you might store this author’s name; all three different ways of storing data are shown for comparison, and all are perfectly valid.

sessionStorage.setItem('author','Peter Gasston');

sessionStorage['author'] = 'Peter Gasston';

sessionStorage.author = 'Peter Gasston';

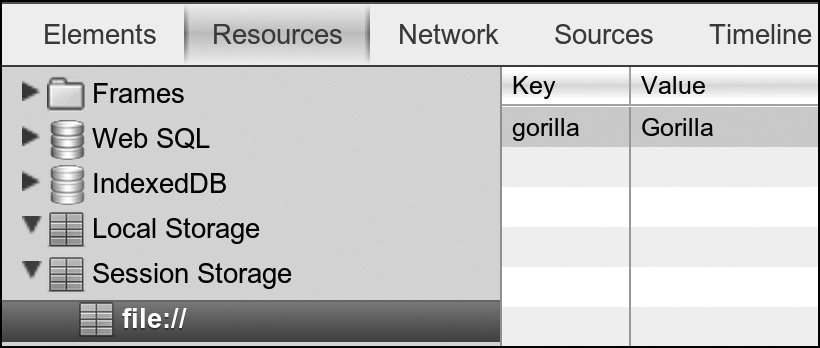

Some developer tools allow you to inspect the contents of storage, so Figure 6-7 shows the result of this code, regardless of which approach you use.

Retrieving items from storage is just as flexible a process; you can use the getItem() method, which accepts only the name of the relevant key as an argument, or the square bracket or dot notation method without any value. In the next code snippet, all three techniques are shown and are equivalent:

var author = sessionStorage.getItem('author');

var author = sessionStorage['author'];

var author = sessionStorage.author;Note

Although I’m storing only very simple values in these examples, in most browsers, you can store up to 5MB of data for each subdomain. This is the figure recommended in the specification, although it’s not mandatory.

You can delete a single item from storage using the removeItem() method, which like getItem(), takes a single key name as an argument and deletes the stored item with the matching key:

sessionStorage.removeItem('author');

In the file storage.html, I’ve put together a simple demo that adds and removes items from the storage. To see the result, you need developer tools that show the contents of the storage, such as in the Resources tab of the WebKit Web Inspector. The contents don’t update in real time, so you have to refresh to see changes.

The nuclear option to remove all items in storage (although only on the specific domain storing them, of course) is the clear() method:

sessionStorage.clear();

A storage event on localStorage is fired whenever storage is changed. This returns an object with some useful properties such as key, which gives the name of the key that has changed, and oldValue and newValue, which give the old and new values of the item that has changed. Note this event fires only on other open instances (tabs or windows) of the same domain, not the active one; its utility lies in monitoring changes if the user has multiple tabs open, for example.

The next code block runs a function that fires whenever storage is modified and logs an entry into the console. You can try it yourself in the file storage-event.html, but you’ll need to open the file and developer console in two different tabs to see the changes occur—remember, changes to the value will show in the other window, not the one where the click occurs.

window.addEventListener('storage', function (e) {

var msg = 'Key ' + e.key + ' changed from ' + e.oldValue + ' to ' + e.newValue;

console.log(msg);

}, false);

Storage is being taken even further with the development of the Indexed Database (IndexedDB) API, which aims to create a full-fledged storage database in the browser that you access via JavaScript. Many browsers have already made an attempt at this, but the vendors couldn’t decide on a common format. IndexedDB is an independently created standard aimed at keeping everyone happy. Its heavily technical nature takes it out of the scope of this book, but if you need advanced storage capabilities, keep it in mind.