Application Cache

Users have certain expectations of website-delivered apps, notable among them is that the apps should work offline or at least save data if the connection is lost. One way to provide offline assets is to save the data in local storage using the API I talked about in Web Storage, but a better approach might be to use the Application Cache, or AppCache. This is an interface that lists files that should be downloaded by the user agent and stored in the memory cache for use even when a network connection is unavailable.

The first step in making an AppCache is to create a manifest file, a text file with the suffix .appcache, which must be served with the text/cache-manifest MIME type. Link to this manifest using the manifest attribute of the html element on every page that you want to make available offline:

<html manifest="foo.appcache">

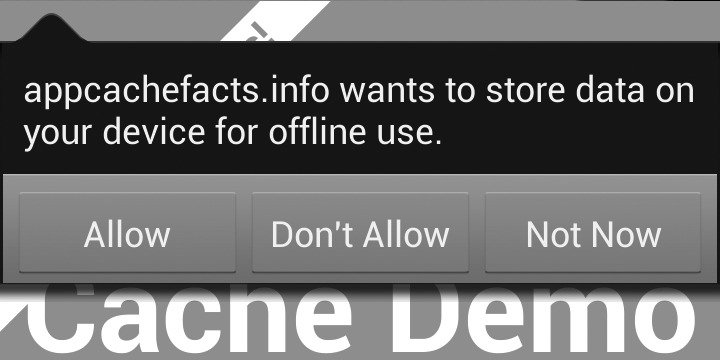

Some browsers alert the user that your application is asking to store files offline and request permission to do so. Figure 10-1 shows how this looks in Firefox on Android.

You need to consider a number of gotchas with the application cache if you’re thinking of using it on your site. These were exhaustively listed in Jake Archibald’s article “Application Cache is a Douchebag,” published on A List Apart (see Appendix K). I touch on a few of these in the following sections.

Contents of the AppCache File

The .appcache file begins with the words CACHE MANIFEST and then follows with a list of all files that should be cached. Each file is on a new line, and you can add single-line comments by entering a hash (#) at the start of each line.

The following listing shows a manifest file that stores three files in the cache. The comment with the version and date isn’t required but will come in handy later:

CACHE MANIFEST # Version 0.1, 2013-04-01 index.html foo.css foo.js

You don’t need to explicitly list the pages to which the .appcache file is linked, because any page that includes the manifest attribute on the html element will be cached by default. These automatically cached pages are known as master entries, whereas files listed in the manifest are known as explicit entries. If some files require online access (such as access to a database using JavaScript), you can create a kind of whitelist of files to always be loaded over the network by listing them after the NETWORK: header. These files are known as network entries.

In the following example, files listed in the /dynamic folder will be loaded over the network instead of from the cache:

NETWORK: /dynamic

You can also add fallback files in case an attempt to load a resource fails, owing to the loss of a network connection or something else. You do this below the FALLBACK: header, where each new line lists a file or folder with the fallback file after it, separated by a space.

In the following example, if any file from the /templates folder fails to load the page, fallback.html will be displayed from the cache instead:

FALLBACK: /templates/ fallback.html

These files are known as fallback entries and, along with the three previous entries, complete the categories of file that will be cached.

The Caching Sequence

When the browser loads your page, it first checks for the manifest file. If the manifest exists and hasn’t been loaded before, the browser loads the page elements as usual and then fetches copies of any files that are in the manifest but haven’t yet been loaded. The browser stores all the listed entries in the cache to be loaded on the next visit.

If the manifest file exists and has been loaded before, the browser loads all the files held in the cache first, followed by any other files that are required to load the page. Next, it checks to see if the manifest file has been updated and, if so, downloads another copy of all the listed files. These files are then saved into the cache and used the next time the page is loaded; they won’t be presented to the user immediately.

One important peculiarity is that in order for the browser to check for new versions of files to be loaded, the manifest file itself must be changed. This is where the version number or timestamp comment comes in handy: Changing either (or both) tells the browser that the manifest has been updated, and it will then download the updated files.

The AppCache API

If you need to access the cache through JavaScript, you can use the window.applicationCache object. This object contains some properties and methods that you’ll find useful if you want to force downloads of updated files after the initial page load or otherwise interact with the manifest.

The status property returns the current status of the cache, with a numeric value and named constant for each state as follows:

-

0 (UNCACHED) means that no cache is present.

-

1 (IDLE) means that the cache is not being updated.

-

2 (CHECKING) means that the browser is checking the manifest file for updates.

-

3 (DOWNLOADING) means that new resources are being added.

-

4 (UPDATEREADY) means that a new cache is available.

-

5 (OBSOLETE) means that the current cache is now obsolete.

You can force a check of the manifest file using the update() method, which checks to see if the manifest file has been updated. The update() method gives the status property a value of 2 while it checks the manifest; it gives a value of 3 if updated resources exist and are downloading, and a value of 4 when updated files are ready.

When the status value is 4, you can use the swapCache() method to load the updated files. At this point, remember the browser has loaded the currently cached version of some files for the user in order to speed up the page load, and any updated files in the cache won’t be presented to the user until the page is reloaded. To get around this, you can use an AppCache event, which fires at various points of the cache cycle, most notably when the status property updates. For example, when the status value becomes 2, the checking event fires, and when it becomes 3, the downloading event fires.

The following code shows one approach to reloading a page with updated assets. Here, the updateready event fires when a new cache has been downloaded and then runs a function that double-checks that the status property has a value equivalent to UPDATEREADY (4). If so, updateready swaps the cache and then asks the user if it’s okay to upload the latest version of the files by reloading the page.

var myCache = window.applicationCache;

myCache.addEventListener('updateready', function(e) {

if (myCache.status === myCache.UPDATEREADY) {

myCache.swapCache();

if (confirm('Load new version?')) {

window.location.reload();

}

}

}, false);

By requesting permission to reload the page, this script ensures that the user doesn’t suddenly lose data or have an action interrupted by a forced reload. This approach is used by many popular web apps, including Google’s suite of tools.