New Elements in HTML5

One of the major new features in HTML5 is a range of new semantic elements, extending the suite far beyond its roots in marking up scientific documents with headings, lists, and paragraphs. Most of the new elements are aimed at giving a page better structure and developers more options for marking up areas of content than just using a div with an associated id or classes.

Here’s one example. In the past, developers might have used this:

<div class="article">…</div>

In HTML5, they have the option of using this:

<article>…</article>

The W3C’s HTML5 spec lists ten structural elements. Of these, three already existed in HTML4: body, h1–h6 (if we cheat a little and count them as a single entity), and address. Of the seven new elements, four are what are known as sectioning content; I’ll get to what this means in a little while, but for now here’s the list:

-

article . An independent part of a document or site, such as a forum post, blog entry, or user-submitted comment

-

aside . An area of a page that is tangentially connected to the content around it, but which could be considered separate, like a sidebar in a magazine article

-

nav . The navigation area of a document, an area that contains links to other documents or other areas of the same document

-

section . A thematic grouping of content, such as a chapter of a book, a page in a tabbed dialog box, or the introduction on a website home page

The other three structural elements define areas within the sectioned content:

-

footer . The footer of a document or of an area of a document, typically containing metadata about the section it’s within, such as author details

-

header . Possibly the header of a document, but could also be the header of an area of a document, generally containing heading (

h1–h6) elements to mark up titles -

hgroup . Used to group a set of multiple-level heading elements, such as a subheading or a tagline

HTML5 has other new elements that don’t affect the basic structure of a page; I’ll cover them where necessary throughout the rest of this book. For now, let’s look further into the reason these new elements were created in the first place.

What’s the Point?

The stated aim of these new elements is to provide clear document outlines for better parsing by the browser and other machines, notably assistive technology like screen readers. Consider these outlines to be like document maps, showing the hierarchy of the content within, which headings are most important, the parent-child relationships between content areas, and so on.

In HTML4, this task was mostly done using the header elements, h1 through h6: The h1 would be unique or the most important heading on the page, h2 elements were usually the direct children of h1, and so on. Seeing something like this was fairly common:

<h1>Great Apes</h1>

<h2>Gorilla</h2>

<h3>Eastern Gorilla</h3>

…

<h3>Western Gorilla</h3>

…

<h2>Orangutan</h2>

…

Nesting headings in this way creates this document outline:

-

Great Apes

-

Gorilla

-

Eastern Gorilla

-

Western Gorilla

-

-

Orangutan

-

Note

Great ape fans will notice that I’ve left out the bonobo and the chimpanzee. That’s for reasons of space and clarity, not because of any bias.

The structure I’ve created makes visual sense, and using headings in this way to create a document outline is known as implicit sectioning.

In HTML5, the sectioning content elements introduced earlier in this chapter create the sections in the outline, not the headers within those sections. This is explicit sectioning. So to get the same structure with our Great Apes markup in HTML5, we’d go for something like this:

<h1>Great Apes</h1>

<section>

<h1>Gorilla</h1>

<article>

<h1>Eastern Gorilla</h1>

…

</article>

<article>

<h1>Western Gorilla</h1>

…

</article>

</section>

<section>

<h1>Orangutan</h1>

…

</section>

The resulting outline would be the same as in the HTML4 example because each section or article element creates a new section in the outline. These are the sectioning content elements I mentioned earlier, along with aside and nav.

Each outline section should have a heading—any heading will do. In my example, I’ve used all h1 headings, but the heading level used doesn’t really matter because the sectioning content is what creates new sections. I could have rolled a die and used that number for each heading level for all the difference it makes.

Note

I’m being a little glib here. You can (and should) still use h1 to h6 in a hierarchical way, as it aids in backward compatibility and makes styling easier.

As well as the heading (or headings, and possibly an hgroup element to wrap them in), each section can contain a distinct header and footer, plus further sections and sectioning roots. These roots are elements such as blockquote and figure, which can have their own outlines but don’t contribute to the overall document outline.

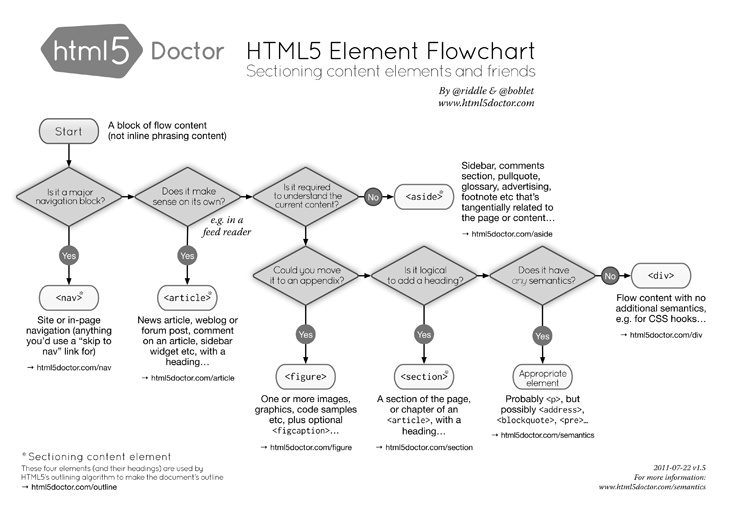

If this discussion isn’t making a lot of sense to you, you’re in good company. The confusion over what each of the sectioning content elements does is so common that the good HTML5 Doctor has created a flowchart (Figure 2-1) to help you choose the right element for the task at hand.

A flowchart. To help you choose an element. If you’re a good judge of tone, you might have started to get the impression that I’m not a fan of the new HTML5 structural elements. If so, you’re right.

The Downside of HTML5 Sectioning Elements

As implied through my perceivable mounting sense of frustration in the previous section, coming to grips with some of these new elements can be quite challenging, especially understanding the difference between article and section. To recap: A section can contain articles and sections, and an article can contain sections and articles, and both make sections in the outline. There is a difference between the two, but no one—not even the writer of the spec—has yet managed a definition so clear and succinct that developers remember it easily.

In his book The Truth About HTML5 (CreateSpace, 2012), Luke Stevens says this about the vague description of article:

Specifications fail when they leave things up to you to work out. The whole point of a specification is to specify exactly what you should do. But here it’s open to interpretation, has no clear benefit, and repeats existing functionality. …

I can’t disagree. My prediction is that these elements will be badly misused by many people unless clearer definitions can be found.

For technical reasons, I suggest not using the new elements on the open Web: For one, they’re simply not supported in older versions of Internet Explorer (8 and below). To make those browsers recognize the new elements, you have to create them in JavaScript. You can do this fairly easily; just implement the popular HTML5Shiv using conditional comments:

<!--[if lt IE 9]> <script src="html5shiv.js"></script> <![endif]-->

But doing this creates a dependency on JavaScript for your visitors; anyone using old IE with JavaScript disabled doesn’t see any of the content contained inside the new elements. Although that may be only a small percentage of users, accessibility should mean that everyone gets to see your content.

On top of that, no currently available browsers support the new outlining algorithm (the JAWS screen reader does, albeit with bugs), so all your hard work doesn’t really have much benefit—this is likely to change in the future, of course.

In the end, the decision to use the new structural elements is, of course, up to you. They’re not mandatory—you can still use div elements as you do currently. I find it hard to recommend using them, however, unless you’re prepared to read the HTML5 spec and fully understand exactly how the new elements work on the outline of a document—and you’re working in an environment where legacy browsers aren’t an issue. As things are at the time of writing, I would look for an alternative way to show page structure. Luckily, one is available, in the shape of WAI-ARIA.