Client-side Form Validation

The new input types are really useful, but perhaps HTML5’s greatest gift to developers is native client-side error checking. Checking the contents of a form before it’s submitted is extremely important for security and usability, and until now, we haven’t had a simple way to do so, although many hundreds of JavaScript libraries have been written to work around this.

Now, with native form validation, many browsers will automatically warn you that the value you’ve entered into a field doesn’t match the input type. In Firefox, for example, if you type only numbers into an email input or omit the http:// protocol from the start of a URL in a url input, a glowing red rule around the input field warns you that the values are incorrect, as you can see in Figure 8-11.

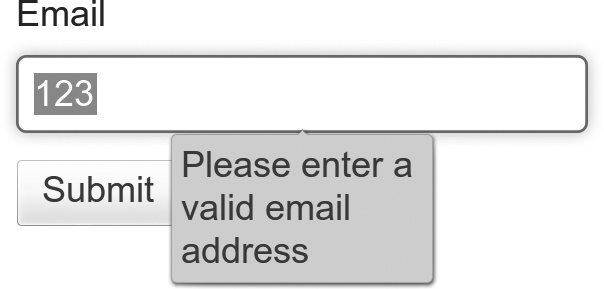

If you try to submit the form now, you’ll receive an on-screen error message, such as the one in Figure 8-12—if, that is, your browser has implemented client-side validation. Each browser that has implemented it has its own style.

If you delete the content of the field and then click Submit again, no error is displayed. This field is optional by default, so not supplying a value is valid, but an incorrectly formatted value is invalid. To make the field not optional, you can add the Boolean required attribute:

<input type="email" required>

This attribute forces the browser to check the value of the field; an empty or improperly formatted value is invalid and returns an error, and only a properly formatted value allows you to submit the form.

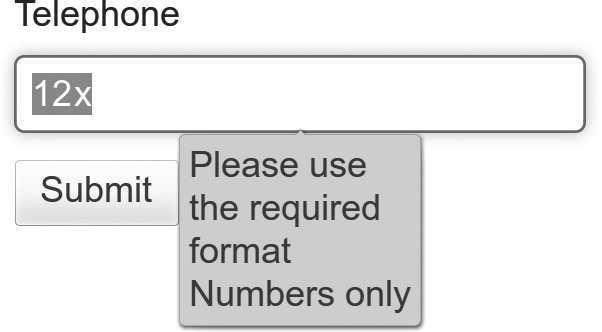

The field’s type determines the pattern of the value format—email requires an email address, url requires a URL with protocol, date requires a year, month, and day, and so on—but you can override this requirement with the pattern attribute. The value for pattern is a regular expression, or regex, a standardized way of matching strings of data across many programming languages. As a simple example, you might want to allow only numbers in a tel input:

<input type="tel" pattern="\d*">

If you try to submit this input with letters or non-numeric characters, you’ll receive a different error message, asking you to use the correct pattern. You can customize this error message in some browsers by adding extra text in the title attribute; in this example, the words “Numbers only” are added to the on-screen message, as you can see in Figure 8-13.

<input type="tel" pattern="\d*" title="Numbers only">

It’s far, far beyond the scope of this book to explain regular expressions in any more detail (to be honest, I barely understand them myself). You can find some useful regex generators online that will help if you need it. (There’s one listed in Appendix I.)

If you want to disable validation on an entire form, you can do so with the novalidate attribute. This attribute prevents any of the validation processes from running, regardless of the required state or pattern matching:

<form action="foo" novalidate>…</form>

And you can do this at a more local level with the formnovalidate attribute on an input or button element.

<button type="submit" formnovalidate>Go</button>

This option is useful when you want to have an option to submit without validation. For example, in a content management system, allowing the user to save a page for editing at a later date, without publishing it, is quite common; the data might be in an incomplete state and invalid, so running validation would only annoy the user.