Microdata

HTML5 has addressed the semantic issue with the creation of a simple syntax called microdata. This is essentially a series of name-value pairs that provide meaningful machine-readable data. As always, before trying to explain it, showing you how it works is easier:

<p itemscope>I live in <span itemprop="city">London</span></p>

This markup creates a single item. The attribute itemscope is used on the containing element to mark the limits, or scope, of this particular item. Inside we have the name-value pair, known as a property: The value of the itemprop attribute is the name—which, in this example, is city—and the element’s content is the value—in this case, London. The result is an item with a single property:

city: 'London'

But you’re not limited to a single property per item; you can have as many as you like:

<p itemscope>Hello, my name is <span itemprop="given-name">Peter</span> and I’m <span itemprop="role">a developer</span> from <span itemprop="city">London</span>.</p>

In this case, the item’s property list looks like this:

given-name: 'Peter' role: 'a developer' city: 'London'

As you can see, this markup is somewhat similar to RDFa, and just like that format, you can give different values to machines and humans. Look at this example where I use the datetime attribute:

<p itemscope>My birthday this year is on <span itemprop="birthday" datetime="2013-12-14">December 14</span>.</p>

And, as with RDFa, you can describe content with predefined schema by linking to it with the itemtype attribute:

<p itemscope itemtype="http://example.org/birthday">My birthday this year is on <span itemprop="birthday" datetime="2013-12-14">December 14</span>.</p>

You can use schema such as the previously mentioned Dublin Core, or even one of your own invention, as I just showed in the previous code block.

The Microdata API

Microdata has a companion DOM API, which is useful for extracting the data from the page and is already fairly broadly implemented in modern browsers. The key to the API is the getItems() method, which returns a NodeList containing all of the items on the page:

var items = document.getItems();

From there, you can choose a single item and, for example, see how many properties it contains using the properties object:

var firstItemLen = items[0].properties.length;

Or you can discover the value of one of those properties:

var itemVal = items[0].properties['name'][0].itemValue;

You can see these demonstrated in the example file microdata-api.html. I’ve logged the results in the console, so open up your favorite browser and take a look. I encourage you to play around with it yourself. For anyone who doesn’t have a browser handy, Figure 2-2 shows how the results are logged in Firebug.

Microdata, Microformats, and RDFa

If you’ve decided that adding machine-readable semantic data to your pages is the right way to go, which format should you use? The answer, of course, is it depends. Evaluate your content, read about the strengths and weaknesses of each of the data types, and decide which one’s best for you.

My personal feeling is that in the future we’ll mostly see a mixture of microdata with simple microformats. One of the interesting things about microdata is that it’s capable of accommodating both of its contemporaries within its own flexible syntax. For example, here’s how to mark up hCard using microdata:

<div itemscope itemtype="http://microformats.org/profile/hcard"> <p><a href="http://about.me/petergasston" itemprop="url fn">Peter Gasston</a> writes for <a href="http://broken-links.com" itemprop="url org">Broken Links</a>.</p> </div>

Likewise, you can easily use RDFa data schema:

<p itemscope itemtype="http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/date" datetime="2013-04-01">April 1</p>

In my opinion, microdata’s flexibility will lead to it being used more and more. That said, it’s not perfect for everything; some microformats, such as Rel-Tag, are so concise and easy to use that’s there’s little point in trying to replace them.

Schema.org

One good reason for using microdata, and another reason I think it’s set to conquer microformats and RDFa, is that you might receive a nice advantage and get your content noticed and promoted by search engines and portals. In 2011 four big Web giants—Google, Microsoft, Yahoo!, and Yandex—launched a new website, Schema.org, which introduced a set of shared vocabularies for marking up common patterns using microdata.

Those patterns include reviews, events, places, items, and objects, things that get discussed frequently across the Web. To illustrate, say you’re writing a book review on your website (I’ve chosen a book at random and given it an unbiased review):

<div class="review"> <h1>The Book of CSS3, by Peter Gasston</h1> <p>What an amazing book! 5 stars!</p> </div>

This review actually contains two items: the details of the book and a review of it. Schema.org has two vocabularies that you can use to mark this up semantically: they are Book and Review. A visit to the relevant sections shows me which microdata patterns I should use. With that done, I can update my markup:

<div class="review" itemscope itemtype="http://schema.org/Review"> <h1><span itemprop="itemReviewed">The Book of CSS3</span>, by <span itemprop="creator">Peter Gasston</span></h1> <p><span itemprop="reviewBody">What an amazing book!</span> <span itemprop="reviewRating">5</span> stars!</p> </div>

Although my markup has gotten more complex, it means more now. Each of the vocabularies I’ve used is defined with a link to the relevant schema in the itemtype attribute, and the items are marked up with preset itemprop values.

What’s interesting about Schema.org is the way that specific schema inherit properties from broader ones; Book, for example, has properties from its own schema, the broader CreativeWork vocabulary, and the top-level Thing (great name!), which has the most generic properties.

By marking up my content using Schema.org patterns, all of the crawlers that reach my page will know the author and title of this book, the fact that I’m reviewing it, and that I gave it a five-star rating. If someone searches for that book, my review could appear in the search results or be aggregated with others to provide a decent overview to the reader.

Rich Snippets

The method of giving extra information in search results, which is used by many search engines, is known by Google as rich snippets. Rich snippets give a user’s search query more context, allowing the user to better evaluate the relevance of the result without having to click through to the page. You can see an example of a rich snippet in Figure 2-3.

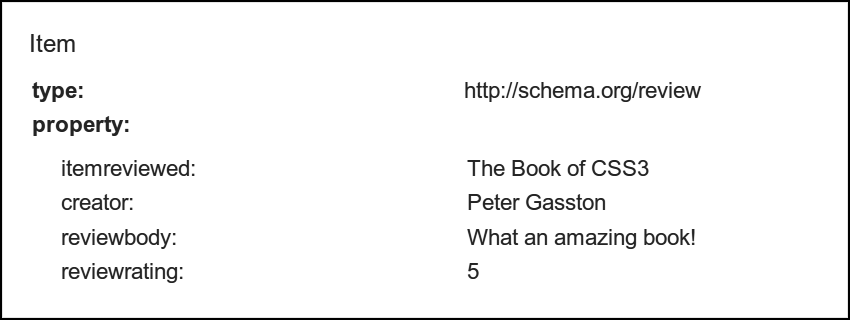

Rich snippets work with microformats and RDFa, but its preferred syntax is microdata. Plenty of information and documentation is available for developers on Google’s Webmaster pages, including a useful tool to test if your microdata is formatted correctly. In Figure 2-4, you can see the data this tool has extracted from the book review created in the previous section.