In this section, we will try to glean information about the web software, operating system, and applications that run on the web server, by using error-handling techniques. From a hacker's point of view, it is not that useful to gather information from error handling. However, from a pentester's point of view, it is very important because in the pentesting final report that is to be submitted to the client, you have to specify the error-handling techniques.

The logic behind error handling is to try and produce an error in a web server, which returns the code 404, and to see the output of the error page. I have written a small code to obtain the output. We will go line-by-line through the following code:

import re

import random

import urllib

url1 = raw_input("Enter the URL ")

u = chr(random.randint(97,122))

url2 = url1+u

http_r = urllib.urlopen(url2)

content= http_r.read()flag =0

i=0

list1 = []

a_tag = "<*address>"

file_text = open("result.txt",'a')

while flag ==0:

if http_r.code == 404:

file_text.write("--------------")

file_text.write(url1)

file_text.write("--------------\n")

file_text.write(content)

for match in re.finditer(a_tag,content):

i=i+1

s= match.start()

e= match.end()

list1.append(s)

list1.append(e)

if (i>0):

print "Coding is not good"

if len(list1)>0:

a= list1[1]

b= list1[2]

print content[a:b]

else:

print "error handling seems ok"

flag =1

elif http_r.code == 200:

print "Web page is using custom Error page"

breakI have imported three modules re, random, and urllib, which are responsible for regular expressions, to generate random numbers and URL-related activities, respectively. The url1 = raw_input("Enter the URL ") statement asks for the URL of the website and store this URL in the url1 variable. Next, the u = chr(random.randint(97,122)) statement creates a random character. The next statement adds this character to the URL and stores it in the url2 variable. Then, the http_r = urllib.urlopen(url2) statement opens the url2 page, and this page is stored in the http_r variable. The content= http_r.read()statement transfers all the contents of the web page into the content variable:

flag =0

i=0

list1 = []

a_tag = "<*address>"

file_text = open("result.txt",'a')The preceding piece of code defines the variable flag

i and an empty list whose significance we will discuss later. The a_tag variable takes a value "<*address>". A file_text variable is a file object that opens the result.txt file in append mode. The result.txt file stores the results. The while flag ==0: statement indicates that we want the while loop to run at least one time. The http_r.code statement returns the status code from the web server. If the page is not found, it will return a 404 code:

file_text.write("--------------")

file_text.write(url1)

file_text.write("--------------\n")

file_text.write(content)The preceding piece of code writes the output of the page in the result.txt file.

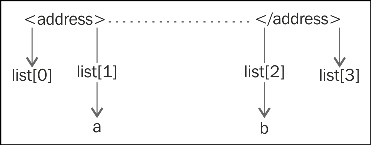

The for match in re.finditer(a_tag,content): statement finds the a_tag pattern which means the <address> tag in the error page, since we are interested in the information between the <address> </address> tag. The s= match.start() and e= match.end() statements indicate the starting and ending point of the <address> tag and list1.append(s). The list1.append(e) statement stores these points in the list so that we can use these points later. The i variable becomes greater than 0, which indicates the presence of the <address> tag in the error page. This means that the code is not good. The if len(list1)>0: statement indicates that if the list has at least one element, then variables a and b will be the point of interest. The following diagram shows these points of interest:

Fetching address tag values

The print content[a:b] statement reads the output between the a and b points and set flag = 1 to break the while loop. The elif http_r.code == 200: statement indicates that if the HTTP status code is 200, then it will print the "Web page is using custom Error page" message. In this case, if code 200 returns for the error page, it means the error is being handled by the custom page.

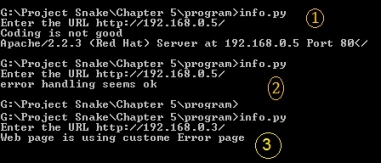

Now it is time to run the output and we will run it twice.

The output when the server signature is on and when the server signature is off is as follows:

The two outputs of the program

The preceding screenshot shows the output when the server signature is on. By viewing this output, we can say that the web software is

Apache, the version is 2.2.3, and the operating system is Red Hat. In the next output, no information from the server means the server signature is off. Sometimes someone uses a web application firewall such as mod-security, which gives a fake server signature. In this case, you need to check the result.txt file for the full detailed output. Let's check the output of result.txt, as shown in the following screenshot:

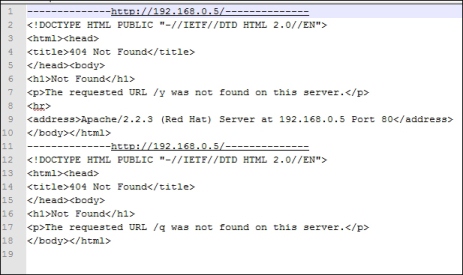

Output of the result.txt

When there are several URLs, you can make a list of all these URLs and supply them to the program, and this file will contain the output of all the URLs.

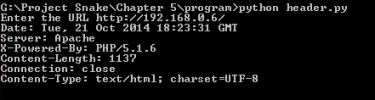

By viewing the header of the web pages, you can get the same output. Sometimes, the server error output can be changed by programming. However, checking the header might provide lots of information. A very small code can give you some very detailed information as follows:

import urllib

url1 = raw_input("Enter the URL ")

http_r = urllib.urlopen(url1)

if http_r.code == 200:

print http_r.headersThe print http_r.headers statement provides the header of the web server.

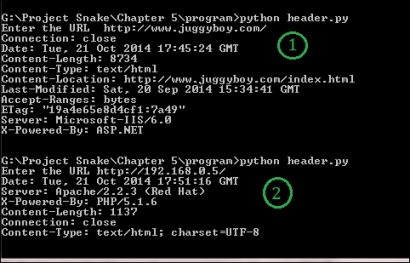

Getting header information

You will notice that we have taken two outputs from the program. In the first output, we entered http://www.juggyboy.com/ as the URL. The program provided lots of interesting information such as Server: Microsoft-IIS/6.0 and X-Powered-By: ASP.NET; it infers that the website is hosted on a Windows machine, the web software is IIS 6.0, and ASP.NET is used for web application programming.

In the second output, I delivered my local machine's IP address, which is http://192.168.0.5/. The program revealed some secret information, such as that the web software is Apache 2.2.3, it is running on a Red Hat machine, and PHP 5.1 is used for web application programming. In this way you can obtain information about the operating system, web server software, and web applications.

Now, let us look at what output we will get if the server signature is off:

When the server signature is off

From the preceding output, we can see that Apache is running. However, it shows neither the version nor the operating system. For web application programming, PHP has been used, but sometimes, the output does not show the programming language. For this, you have to parse the web pages to get any useful information such as hyperlinks.

If you want to get the details on headers, open dir of headers, as shown in the following code:

>>> import urllib

>>> http_r = urllib.urlopen("http://192.168.0.5/")

>>> dir(http_r.headers)

['__contains__', '__delitem__', '__doc__', '__getitem__', '__init__', '__iter__', '__len__', '__module__', '__setitem__', '__str__', 'addcontinue', 'addheader', 'dict', 'encodingheader', 'fp', 'get', 'getaddr', 'getaddrlist', 'getallmatchingheaders', 'getdate', 'getdate_tz', 'getencoding', 'getfirstmatchingheader', 'getheader', 'getheaders', 'getmaintype', 'getparam', 'getparamnames', 'getplist', 'getrawheader', 'getsubtype', 'gettype', 'has_key', 'headers', 'iscomment', 'isheader', 'islast', 'items', 'keys', 'maintype', 'parseplist', 'parsetype', 'plist', 'plisttext', 'readheaders', 'rewindbody', 'seekable', 'setdefault', 'startofbody', 'startofheaders', 'status', 'subtype', 'type', 'typeheader', 'unixfrom', 'values']

>>>

>>> http_r.headers.type

'text/html'

>>> http_r.headers.typeheader

'text/html; charset=UTF-8'

>>>